*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 74935 ***

[Pg 1]

LESSONS

from

THE LIFE OF

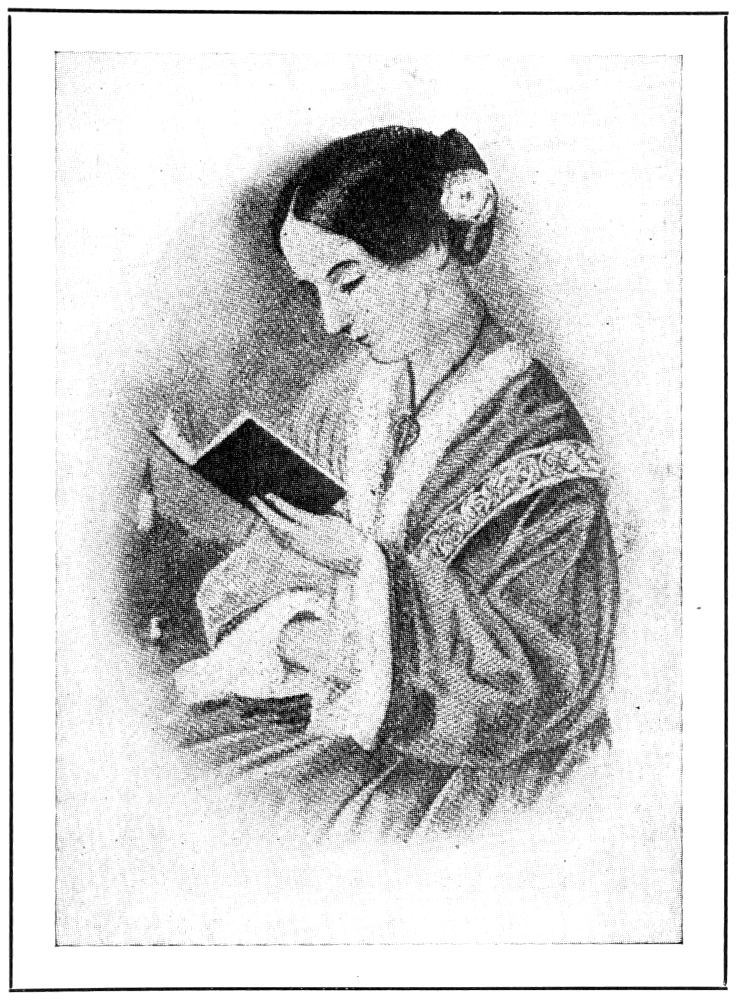

Florence Nightingale

By CHARLOTTE A. AIKENS

Author of “Hospital Training School Methods and

the Head Nurse,” “Primary Studies for Nurses,”

“Clinical Studies for Nurses,” “Studies in Ethics for

Nurses,” etc. Joint Author of Hospital Management.

Editor “The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review.”

Lakeside Publishing Company

38-40 West 32nd St.

New York.

[Pg 2]

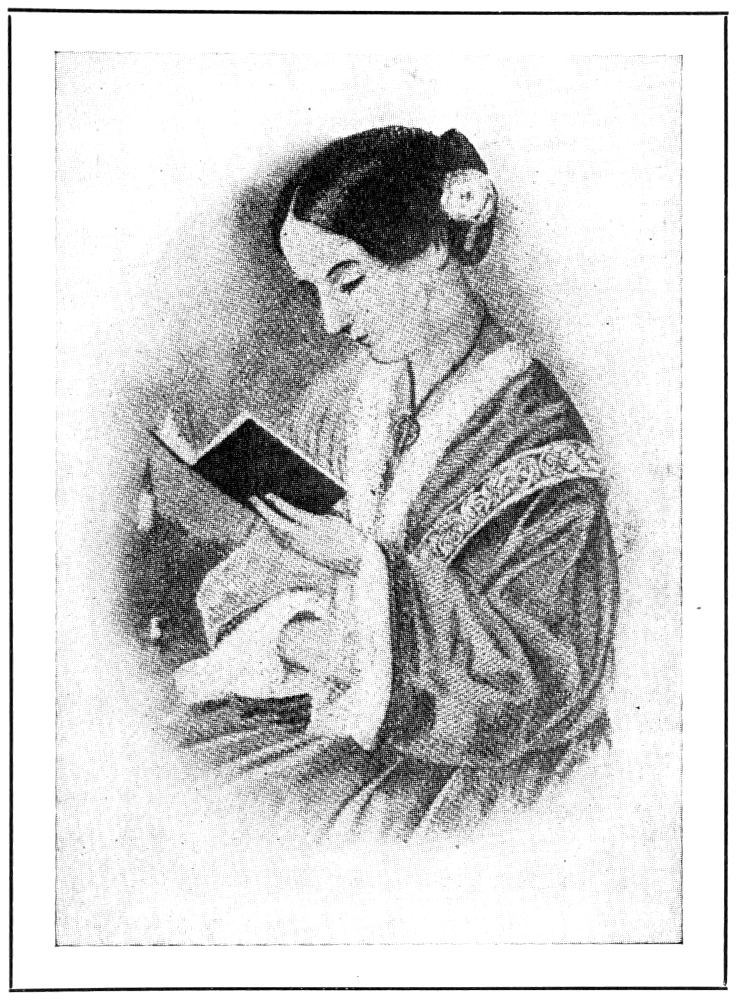

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE

Born in Florence, Italy, May 12th, 1820;

died in London

August 13th, 1910

[Pg 3]

SANTA FILOMENA

By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Whene’er a noble deed is wrought

Whene’er is spoke a noble thought

Our hearts, in glad surprise,

To higher levels rise.

The tidal wave of deeper souls

Into our inmost being rolls

And lifts us unawares

Out of all meaner cares.

Honor to those whose words or deeds

Thus help us in our daily needs.

And by their overflow

Raise us from what is low!

Thus thought I, as by night I read

Of the great army of the dead,

The trenches cold and damp,

The starved and frozen camp.

The wounded from the battle-plain

In dreary hospitals of pain,

The cheerless corridors,

The cold and stony floors.

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

And slow, as in a dream of bliss,

The speechless sufferer turns to kiss

Her shadow, as it falls,

Upon the darkening walls.

As if a door in heaven should be

Opened and then closed suddenly,

The vision came and went,

The light shone and was spent.

On England’s annals, through the long

Hereafter of her speech and song

That light its rays shall cast

From portals of the past.

A Lady with a Lamp shall stand

In the great history of the land

A noble type of good

Heroic womanhood.

Nor even shall be wanting here

The palm, the lily and the spear

The symbols that of yore

Saint Filomena bore.

[Pg 5]

Lessons from the Life of

Florence Nightingale

Chapter I.

The presence of thousands of daughters of Florence

Nightingale in the regions devastated by the great

world war, and the great service to humanity which

they have rendered, have turned the thoughts of many

to that other battlefield where the great need of the

world for trained nurses was first impressed on the

hearts of the people—an impression never to be

effaced while there are suffering human beings requiring

skilled care and service.

Sixty odd years ago, at the outbreak of the Crimean

war there were no women nurses to minister to those

who had been wounded in the service of their country.

Woman’s ministry was sorely needed but not wanted

by those in active command of military affairs at the

seat of war. It remained for Florence Nightingale to

teach the world one of its greatest lessons—a lesson

from which future generations will reap increasing

benefits. When the Crimean war closed, the foundation

was begun on which the structure of modern

nursing was to be reared.

In every age, the world has had its heroes, and

Florence Nightingale would have been the last to wish

to give the impression that there were not many

splendid women devoting themselves to the care of the

sick long before she was born. They were not trained

women according to modern ideals of training, but

there were women of gentle birth and breeding, refined

and accomplished who served the sick with singleness

of heart and rare devotion. The world will always owe

its debt of gratitude to the Roman Catholic Sisters

[Pg 6]

and the Deaconesses of other churches, whose tender

ministries to the sick in hospitals and home, did much

to lessen the sum of human suffering in the years

before Miss Nightingale’s great work was begun.

No one who reads the story of the beautiful life of

Florence Nightingale can fail to be impressed with the

fact that the dominant motive of that life was—SERVICE.

It has been aptly said that one of the first and

most important lessons that a nurse needs to learn, is

to spell SELF with a little s. In this she has a worthy

example for forgetfulness of self seems to have been

characteristic of Florence Nightingale all through her

life. Service to humanity—especially service to the

sick and distressed part of humanity—seems to have

made its strong appeal to her almost from childhood.

Organization for service, education and training for

service, plans for service in a hundred different ways—filled

her life, and the story of her many-sided activities,

as revealed by her official biographer—has been

a surprise to those who have thought of her only in

connection with nursing. While she will always be

best remembered as the founder of modern nursing,

her great efforts in improving sanitary conditions in

India, in which she labored unceasingly for many

years with officials in the War Department, and her

work in behalf of reform in the management of workhouses

in England, were closely interwoven with her

work in behalf of better nursing for the sick. Her

voluminous correspondence and her literary work

seem in themselves to have been sufficient to occupy

her full time, after her return from the Crimea.

The popular idea of Florence Nightingale has been

drawn largely from the pen picture of Longfellow in

Santa Filomena, but it is far from being a true picture

of her life. To fully appreciate her character and influence

[Pg 7]

one must study to some extent, not alone the

social and sanitary conditions that prevailed in her

earlier life, but the habits of thought and even the

etiquette of the times, during which her chief work

was being accomplished. Of these conditions her

biographer says:

“Now that the fruits of Florence Nightingale’s

pioneer work have been gathered, and that nursing is

one of the recognized occupations for gentlewomen,

it is not altogether easy to realize the difficulties which

stood in her way. The objections were moral and

social, in large measure rooted to conventional ideas.

Gentlewomen, it was felt, would be exposed, if not to

danger and temptations, at least to undesirable and

unfitting conditions. ‘It was as if I had wanted to be

a kitchen maid,’ Miss Nightingale herself said in later

years. Nothing is more tenacious than social prejudice.

But the prejudice was in part founded on very

intelligible reasons and in part was justified by the

level of nursing as an occupation at that time. It will

suffice to say that though there were better-managed

and worse-managed hospitals, yet there was strong

evidence to show that hospital nurses had opportunities

which they freely used, for ‘putting the bottle to

their lips’ when so disposed, also that other evils were

more or less prevalent.

“The more she heard of the worst, the more was

Florence Nightingale resolved to make things better;

but the more her parents heard, the greater and more

natural was their repugnance. Somebody must do the

rough pioneer work of the world; but one can understand

how the parents of an attractive daughter, to

whom their own life at home seemed to them to open

many possibilities of comfortable happiness, came to

desire that in this case the somebody should be somebody

else.”

[Pg 8]

It is difficult to study her life without feeling that

she was sent into the world especially to accomplish

the great tasks to which in early middle life, her powers

were chiefly devoted. It should, however, be always

remembered that during this period others besides

Miss Nightingale were making their contribution

to better nursing and better sanitary conditions in hospitals,

and in the world outside. Lord Lister, who ushered

in the new era of antiseptic surgery, was seven

years younger than Florence Nightingale. “He and

she, each in the manner in which Nature or Providence

fitted them, were simultaneously inaugurating the new

era, he the foster father, she the foster mother of

myriads of this generation and unthinkable millions

of those who are to be. His methods demanded the

trained nurse both for surgery and midwifery, both for

the battlefield where life is destroyed, and for the lying-in

room where it is ushered into separate existence.

Her work was to provide the training and the principles,

the ideals, the enthusiasm, and the tiniest, humblest

details, whereby the modern nurse is made.”

[Pg 9]

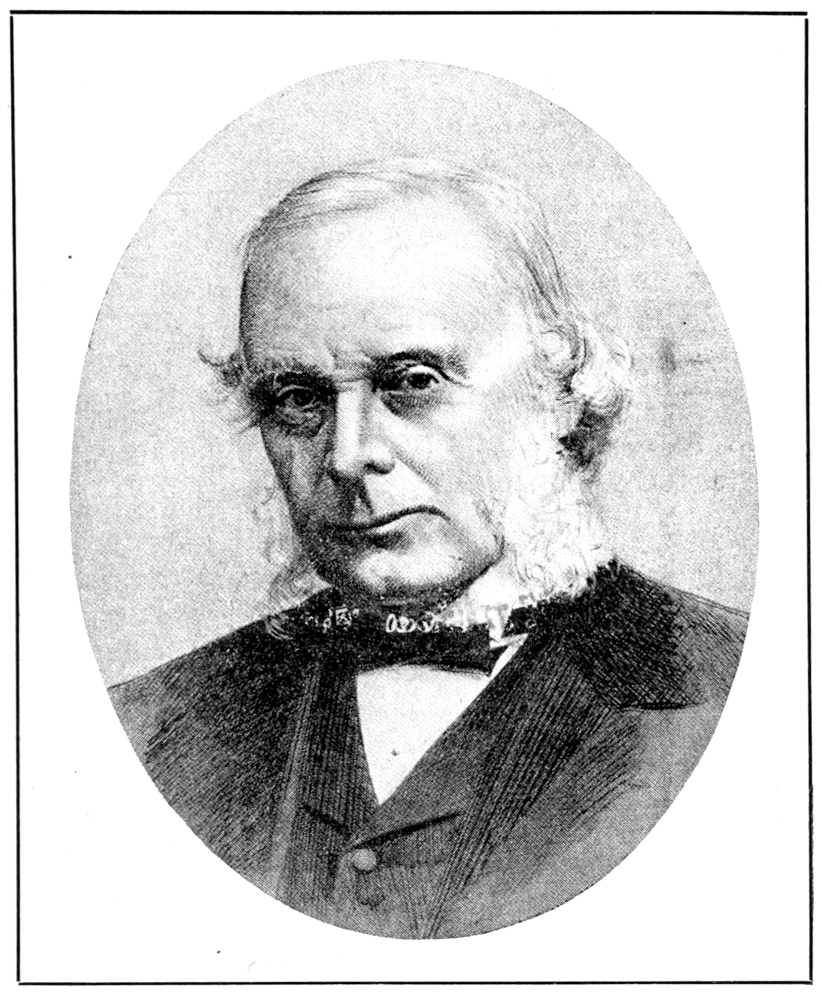

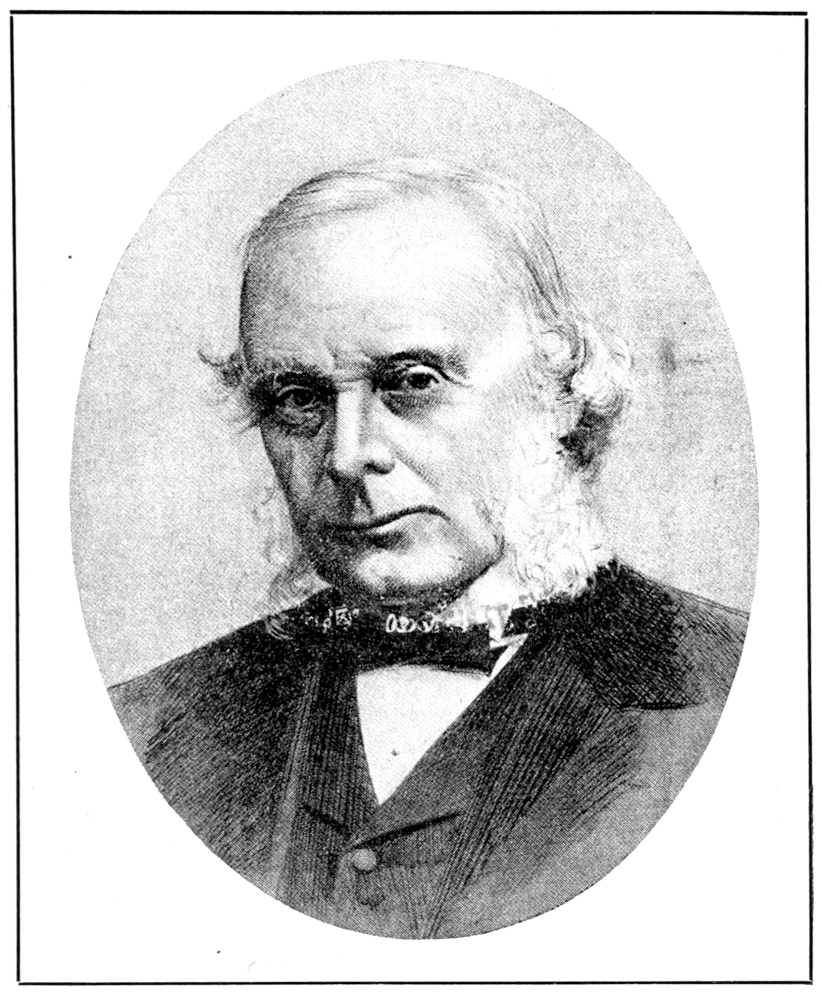

LORD LISTER

Apart entirely from the generally undesirable type

of women (there were many exceptions) found in

charge of the care of the sick when Florence Nightingale

began her work, were the generally undesirable

conditions which existed before Lord Lister’s antiseptic

methods were inaugurated in 1868. Erysipelas, gangrene,

pyemia, and septicemia were common complications

of surgery and the death rate of maternity

patients in hospitals was appalling. A nurse who was

one of the pioneers in improving the care of the sick,

thus describes her experience when she entered for

training in an English hospital:

“New methods of nursing as well as of surgery had

to contend with tremendous difficulties in the way of

[Pg 10]

bad buildings, bad ventilation, old-fashioned furniture,

and lack of apparatus.

“The utensils, which in the hospitals of today are

of white earthenware or enamel, were of exceedingly

battered tin, almost entirely denuded of their original

covering of black japan, and it was absolutely impossible

to keep some of them clean and sweet. Smells

abounded. I have seen a visiting surgeon run through

a ward to escape them, and during my first week I

was much puzzled by the existence of a horrible smell

in one corner of the children’s ward. I privately investigated

the floor and under the beds, but could find

nothing to account for it, but discovered at last that

it came from a patient—a child with a diseased bone

of the face, a case which nowadays would be antiseptically

treated and probably isolated.

“Under the old regime the nurses had, as a rule, no

uniform dress, and cooked their own meals, which

they bought for themselves, in the ward kitchens or

scullery, and these conditions did not at once pass

away.

“The antiseptic treatment of wounds was coming

into general use, and the particular method of the

moment, which had been advocated by Dr. Lister, was

a sort of model steam-engine, which could be carried

about and placed on a table or stand by the side of a

patient’s bed. When a wound was to be attended to,

before the dressings were removed a lamp in this apparatus

was lighted. A strong spray of diluted carbolic

acid then played over the wound the whole time

it was being dressed, much to the discomfort of the

doctors and nurses, whose hands would be stiff with

the carbolic and their ears dulled with the constant

hissing and fizzing of the machine. Everything was

[Pg 11]

saturated with carbolic at that time, wool, bandages,

lint, gauze, etc., but in the course of a few years this

treatment was entirely superseded.

“Operations were comparatively free and easy performances.

We nurses wore our ordinary dresses, and

were kept busy washing sponges, which were used

again and again, though they were boiled between the

operation days. In the medical wards enteric cases

were indiscriminately mixed with others, and tuberculosis

patients stalked about and expectorated freely.”

Nurses of today, in common with the rest of the

world, owe a greater debt of gratitude than most of

them realize to Lord Lister who, by his surgical experiments,

and his demand for trained nurses, helped so

much in laying the foundations for the trained nursing

of today. Other workers in the realm of bacteriology

were aiding greatly in the remarkable developments

which medicine and surgery were making in that

period.

THE SPIRIT OF VOCATION.

An English writer, Miss Margaret Fox, in an address

to nurses has called attention to the great need

of the spirit of vocation in the nurses of today. “Look

at it what way you will,” she states, “the fact remains

that nursing is work demanding something more than

mere business qualities, more than an active intelligence,

more than even sympathy and kindness of

heart. The latter, precious though it is, may be worn

very threadbare in the constant daily contact with all

sorts of unlovely natures suffering from every variety

of trying ailment. Patients are not all grateful, or appreciative,

and you will find some of them by no means

ready to kiss your shadow as you pass on your rounds.

Sometimes they are inclined to grumble because they

[Pg 12]

do not immediately get all they want. Their disease

may make them irritable, captious even, sometimes,

repulsive. These people need more than ordinary

everyday good qualities in a nurse. They need one

who, over and above her professional ability, looks upon

her work as a vocation, ‘a calling by the will of

God.’ It was that spirit which made the best of the

pioneers of other days what they were. Nursing was

undertaken by them as a definite life-work. It cost

them so much to enter upon it, that they were unlikely

to throw it up without some very cogent reason.

Work was not then considered so much a means to

an end. It was the ultimate achievement. Nursing

is a mission; and wherever it is done, it needs the same

spirit of true vocation to do it well, and to persevere

in spite of difficulties.

“There would be fewer restless, discontented

nurses, if each possessed the spirit of vocation. It is

a spirit that gives one the calm, quiet feeling of being

in the only possible place and doing the only possible

work. It stirs in one a large-hearted charity towards

all such as be sorrowful, sick or poor. It makes one

feel, ‘Well, whoever fails, I must not.’ It helps wonderfully

when things are crooked and the work is

hard, or uninteresting. One simply can’t help making

things look nice, or doing the little extra bit which

just makes all the difference.”

The motives which influence an individual to undertake

a task are tremendously important factors in

real and full success, and it is well, in such work as

nursing, that all who enter on it analyze carefully

their own motives in so doing.

There can be no mistaking the motives which led

Florence Nightingale to enter on her career under the

distressing conditions which then prevailed. Born

[Pg 13]

and reared in refined surroundings, in an intellectual

atmosphere, with all the educational advantages the

times afforded, if she had fulfilled parental and popular

expectations, she would have been satisfied to have

spent her girlhood life chiefly in a round of gay social

functions, with ample leisure for study and travel,

and to have married at an early age a man belonging

to her own social circle. That she was not satisfied

with this sort of existence is seen in this typical extract

from one of her letters, written when she was

twenty-six years of age: “The thoughts and feelings

that I have now,” she wrote, “I can remember since I

was six years old. It was not I that made them. A

profession, a trade, a necessary occupation, something

to fill and employ all my faculties, I have always

felt essential to me, I have always longed for, consciously

or not. * * * The first thought and the last

thought I can remember was nursing work, but for

this I have had no education myself. * * *” Later

she wrote: “In my thirty-first year I see nothing desirable

but death. Why do I wish to leave this world?

God knows I do not expect a greater heaven beyond,

but that He would now set me down in St. Gile’s, or at

a Kaiserwerth, there to find my work, and my salvation

in my work.”

To her, life was earnest—it was a serious thing,

and her struggle for many long, weary years to free

herself, to overcome the obstacles that closed in

around her, so that she might accomplish the kind of

work she felt God wanted her to do—her long-continued

effort to gain her relatives’ consent for her to even

attempt nursing—forms one of the most interesting

chapters in her life story. Nursing to her was always

“God’s business.”

[Pg 14]

How much this sense of vocation, this strong feeling

that she was called to do the will of God in this

form of service, had to do with her success, no one can

fully determine, but that it helped tremendously in

carrying her over difficult places cannot be doubted.

As one looks back over her wonderful life and tries to

discern the secret of her remarkable influence, one

cannot but feel that the spirit in which she did her

work, her absolute devotion to the cause to which she

was giving her best powers, accounts in large measure

for her name being honored, and her memory kept

green all over the civilized world. “The sweetest character

in all British history,” was a noted man’s comment

on her, yet the sweetness was always combined

with strength, and courage, and a quiet determination

not to give up because things were harder or more difficult

than she had expected. Her work was not lightly

undertaken, and as lightly abandoned, as nursing is

by many young women today.

One of the outstanding qualities of this great

woman was her individuality, a quality which some

one has aptly said is close kin to honesty. She did her

own thinking, and the results of that independent

thinking were evident all through her career. In commenting

on this quality of individuality, a recent writer,

Byron H. Stauffer, has said:

“It burst out in a letter written when she was eight,

which she closes with: ‘My love to all except Miss

W—.’ It developed in her despising, early in life, the

silly conventionalities of the high society of the day.

It sparkled in explaining why she tittered during a

ritualistic service: ‘The rector was praying “That it

may please Thee to have mercy on all men,” and the

ridiculousness of that prayer broke upon me. Think

of it! If I asked you to have mercy on your own boy,

[Pg 15]

you’d knock me down.’ Another instance of her nonconformity

to the religious conventions lies in her

declaration: ‘I never prayed for George IV; I always

thought that people were very, very good who could

pray for him. It was a wonder to me how he could

possibly be any worse if nobody prayed for him. I

prayed a little for William IV. For the young Victoria

I prayed with rapture.’”

THE PRICE OF SKILL.

One of the tendencies of this age in nurses is to

expect and apply for positions of responsibility for

which they have not taken any special or definite

pains to fit themselves. Their estimate of their own

ability is often much greater than conditions justify;

they often want the best positions without paying the

price of special skill. The determination of Florence

Nightingale to secure for herself the best instruction

the world afforded at that time, and her conviction

that if she was ever to accomplish anything worth

while she must first learn all that was possible under

the circumstances for her to learn about the business

of caring for the sick, is a fine example for those who

really desire to do worth while things in this world.

It has been well said that ability depends greatly

on preparation, and that opportunity is largely dependent

on ability. It was by no accident that Florence

Nightingale became “the angel of the Crimea.”

Nothing that she could do to fit herself for such a task

had been omitted, though she could not know how

great were the opportunities that were to be afforded

her to use the knowledge and experience she was so

determined to secure. She fully realized that to do

good required more than good desires or intentions.

To do good in the way that she wished required some

[Pg 16]

skill. To be the best possible nurse, to fit herself in the

best way, however long it might take, or how hard the

way might be, meant much greater difficulties then

than it could possibly mean now.

When in later years she expressed herself as follows,

she was simply expressing the convictions

which had been with her all through life:

“Nursing is an art, and if it is to be made an art,

it requires as hard preparation as is required for any

painter’s or sculptor’s work; for what is having to do

with dead canvas or cold marble compared with caring

for the living body?”

How to obtain the needed skill was a problem which

she had studied for many years. The difficulties and

moral dangers that stood in the way of a refined

woman securing experience in nursing in a hospital

seemed for years insuperable, and can hardly be appreciated

by the nurses of today.

AT KAISERWERTH.

Through a friend, Miss Nightingale learned of an

institution for deaconesses at Kaiserwerth, Germany,

where there was a school, a hospital and a prison, under

the management of deaconesses. It had a decidedly

higher tone and reputation than prevailed in hospitals

in general, she was told; and Pastor Fliedner’s

annual reports of the work of the institution were

eagerly studied, and used to silence parental objections.

The opportunity to spend a few months at

Kaiserwerth was delayed, but finally came when her

mother and sister, in search of health, went to Carlsbad,

and to travel. In commenting afterward on the

new departure of giving some months of training in

the care of the sick, inaugurated at Kaiserwerth, Miss

Nightingale called special attention to the fact that

[Pg 17]

the Kaiserwerth institutions had begun, not with programs

or fullfledged schemes set forth in a prospectus,

but with individual cases and personal devotion—and

later years showed that her own great work began,

also, not with a prospectus or prearranged program,

but with actual doing of the thing she felt needed to

be done when the opportunity came. The real training

in nursing given at Kaiserwerth was far from satisfactory

to her, but the atmosphere, the spirit of consecrated

service, impressed her deeply.

Later she returned to Kaiserwerth for further apprenticeship

in nursing and followed this experience

by spending some time in the hospitals of Paris presided

over by the Roman Catholic sisters. It is very

evident that she did not expect to have everything she

wished to know, prepared and presented to her to

study. Her powers of observation were wonderful,

and she proved an indefatigable collector of pamphlets,

reports, statistics, methods of work and plans of hospital

organization and management.

One criticism which is often heard of present day

nurses in training is that they so quickly get into ruts

in the matter of observation—that they see so much in

a hospital ward which they fail to perceive—that they

fail to gather practical knowledge pertaining to their

work which is all around them waiting to be picked

up. If Florence Nightingale had been the type of

woman who had to have all the nursing knowledge

which she obtained duly imparted to her by somebody

else appointed for that purpose, her influence on the

conditions which then prevailed would have been small

indeed. Instead, she was constantly getting hold of

facts, reading medical books, continually studying into

the “why” of things, and how they might be improved,

so that better general results might be obtained

in the care of the sick. Her private notebooks

[Pg 18]

were filled with facts, ideas, and suggestions gathered

here, there and elsewhere, which she was later to use

in laying broad foundations for the improvement of

nursing, and of hospital management in general. Her

attention to small details, as found in her notebooks

preserved to the present day, was characteristic of all

her work, and accounts in no small degree for its success.

TACT AND SENSE OF HUMOR.

Among the indispensable qualities for successful

nursing, we place “TACT” very close to the top of the

list. To get along with people without friction, to get

needful things done without arousing antagonism, to

have that keenness of perception, that ready power of

appreciating and of doing or saying what is most fitting

under the circumstances; to maintain, withal,

that quality of mind which enables one to see the

humorous side to otherwise difficult situations, are

qualities to be coveted by every nurse.

How Florence Nightingale succeeded in managing

committees with whom she had to work, as well as

the sense of humor which helped to carry her over

difficult situations, are admirably shown in extracts

from her private letters, written soon after she returned

from Kaiserwerth. She had been importuned

to undertake the management of an institution known

as an “Establishment for Gentlewomen During Illness,”

which had been started, but had been so grossly

mismanaged that it had been threatened with closure.

A change of location had finally been decided on

when Miss Nightingale agreed to undertake its management.

One of the first difficulties which confronted

her is described in the extract from a private letter

to a friend which follows:

[Pg 19]

“My committee refused me to take in Catholic

patients—whereupon I wished them good morning,

unless I might also take in Jews and their Rabbis to

attend them. So now it is settled, and in print, that

we are to take in all denominations, whatever, and allow

them to be visited by their respective priests and

Muftis, provided I will receive (in any case whatsoever

that is not of the Church of England) the obnoxious

animal at the door, take him upstairs myself, remain

while he is conferring with his patient, make myself

responsible that he does not speak to, or look at, any

one else, and bring him downstairs in a noose, and

out into the street. And to this I have agreed! And

this is in print!

“Amen. From committees, charity and schism—from

the Church of England and other deadly sins—from

philanthropy and all the deceits of the Devil—Good

Lord deliver us!”

To her father in 1853, she wrote another characteristic

letter which affords a glimpse of the experience

in “managing” people she was getting at this

time, and which was later to be most helpful in her

great task of helping to reorganize the affairs of the

army hospitals. In this letter, she says:

“You ask for my observations upon my line of

statesmanship. I have been so very busy that I have

scarcely made any resume in my own mind.

“When I entered into service here, I determined

that, happen what would, I never would intrigue

among the committees. Now I perceive that I do all

my business by intrigue. I propose in private to A, B

or C, the resolution I think A, B or C most capable of

carrying in committee, and then leave it to them, and

I always win. * * * I have observed that the opinions

of others concerning you depend not at all, or very

little, upon what you are, but upon what they are.

[Pg 20]

“Last General Committee I executed a series of

Resolutions on five subjects and presented them as

coming from medical men:

“1. That the successor to our house surgeon (resigned)

should be a dispenser, thus saving our bill at

the druggists of 150 pounds per annum.

“2. A series of House Rules, of which I send you

the rough copy.

“3. A series of resolutions about not keeping

patients.

“4. A complete revolution as to diet, which is

shamefully abused at present.

“5. An advertisement for the Institution.

“All these I proposed and carried in committee

without telling them that they came from me, and not

from the medical men; and then, and not till then, I

showed them to the medical men, without telling them

that they were already passed in committee.

“It was a bold stroke, but success is said to make

an insurrection into a revolution. The medical men

have had two meetings upon them and approved them

all, and thought they were their own. And I came off

with flying colors, no one suspecting my intrigue.

“I have also carried my point of having good, harmless

Mr. —— as chaplain, and no young curate to

have spiritual flirtations with my young ladies. So

much for the earthquakes in this little mole-hill of

ours.”

Happy though Miss Nightingale was in this new

work, it did not offer her the wide opportunity for

training nurses, which she greatly longed to do—somewhat

along the lines pursued at Kaiserwerth.

[Pg 21]

[Pg 22]

The Call to Service in the

Crimean War

Chapter II.

When the Crimean war broke out in 1854, it can

easily be imagined that there was no woman in England

so well fitted to take charge of the chaotic situation

which soon developed in regard to the care of

the wounded. The employment of women nurses in

the army was an entire innovation. It excited jealousy

in medical men, and strong criticism from military

officers. In spite of the fact that the idea was certain

to be branded as unwomanly by her own sex, and by

the world in general, she offered her services, and her

letter crossed in the mails a formal offer from Sir Sidney

Herbert of the War Department of the position

of director of a party of women nurses who were to

be sent to nurse the sick. From France, a devoted

company of Sisters of Charity had gone, who were

rendering excellent service to the wounded, and it was

felt by some officials who were not bound hand and

foot by routine and precedent, that a company of

women nurses from England might be sent to assist in

the emergency that had arisen. Her services at this

time are well known. The main facts were tersely

summed up in the following paragraphs, published at

the time of her death:

“The death rate at Scutari was 42 per cent. In

one hospital it rose to 56. Eighty per cent of those

whose limbs were amputated died of gangrene. The

sick list amounted to over 13,000. In the Turkish barracks

on the Bosphorus there were two miles of sick

beds, in a double file along the corridors. The rats

ran over the wounds of the helpless patients.

[Pg 23]

“Miss Nightingale assembled a party of 41 volunteer

nurses, including ten Catholic nuns and eight sisters

of mercy of the Anglican church, and took them

to the Crimea. Upon her arrival at Scutari the “Lady

of the Lamp” went straightway to work to bring order

out of confusion, life out of the jaws of death, heaven

on earth from a veritable hell. The day after her arrival

they brought in the wounded survivors of the

charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava; the next day

came the wounded from the bloody field of Inkerman.

‘Red tape’ insisted that all stores should be inspected

ere being issued to the troops. When she found that

the inspection would take three days Miss Nightingale

broke down the doors and commandeered the supplies.

She had soon reduced the death rate from 42

to 2 per cent. The wounded and the dying followed

her with their eyes in her progress from cot to cot, as

though she were an angel visitant. When, at the close

of the war, a dinner was given the military and naval

officers, those present voted for the one whose services

would longest be remembered by posterity. There was

but one name on every slip of paper—that of Florence

Nightingale.

“She went back to England under an assumed

name, and reached her home before it was known that

she had left Turkey. The queen sent for her and

thanked her in person at Balmoral. Every soldier in

the army contributed a day’s pay to a fund of $250,000

for their benefactor, but she gave it all to found the

Florence Nightingale Training School for Nurses in

London. The Geneva convention and the Red Cross

Society were the eventual outcome of her labors in the

east.”

The difficulties which she had to contend with can

never be fully appreciated at this time when women’s

[Pg 24]

service as nurses in the army in most civilized countries

is well established. Her biographer writing of

that period says:

“Miss Nightingale’s work in the Crimea was attended

by ceaseless worry. She had to fight her way

into full authority. She knew that she would win, but

her enemies were active, and were for the moment in

possession of the field. ‘There is not an official,’ she

said, ‘who would not burn me like Joan of Arc, if he

could, but they know that the War Office cannot turn

me out because the country is with me. * * * The real

grievance against us is that though subordinate to

the medical chiefs in office, we are superior to them in

influence, and in the chance of being heard at home.’”

It is not easy to suggest the many qualities of character

in Miss Nightingale which the experiences in

the Crimea brought out into bold relief—qualities

which are just as much needed in nursing today as

they were then. Her unflinching endurance of the

hardships which the conditions forced upon her; her

generous recognition of the work of others; her

thoughtful care of the nurses who had been entrusted

to her, under the most difficult conditions—should be

remembered quite as much as her wonderful organizing

qualities, her keen insight into situations, and her

general ability to produce results—to bring things to

pass. It was a recognition of these latter qualities that

led Queen Victoria to exclaim: “Such a clear head! I

wish we had her at the War Office.”

After the war was over and a general inquiry as

to conditions and methods of sanitary improvement in

regard to the army had been started in London, an

army doctor writing of her said: “It may surprise

many persons to find from Miss Nightingale’s evidence

that, added to feminine graces, she possesses

[Pg 25]

not only the gift of acute perception, but that on all

the points submitted to her she reasons with a strong,

acute, most logical, and if we may say so, masculine

intellect, that may well shame other witnesses.

They maunder through their subject, as if they had

by no means made up their minds on any one point—they

would, and they would not; and they seem almost

to think that two parallel roads may sometimes be

made to meet, by dint of courtesy and good feeling,

amiable motives that should never be trusted to in

matters of duty. When you have to encounter hydra-headed

monsters of officialism and ineptitude, straight

hitting is the best mode of attack. Miss Nightingale

shows that she not only knows her subject, but feels

it thoroughly. There is, in all she says, a clearness,

a logical coherence, a pungency and abruptness, a

ring as of true metal, that is altogether admirable.”

To have failed in appreciation of the part her assistant

nurses played, during the excitement of wartime

conditions, would have been easy and, to a degree,

excusable—but she did not fail. To take the

whole credit for achievement to oneself is a very human

failing, but it was not one of Florence Nightingale’s

failings.

One illustration of her appreciation of her associates

in the campaign shows this characteristic plainly.

Of one woman whom she had placed in a position

of more than ordinary responsibility, she wrote:

“Without her, our Crimean work would have come to

grief—without her judgment, her devotion, her unselfish,

consistent looking to the one great end—the

carrying out of the work as a whole—without her untiring

zeal, her accuracy in all trusts and accounts,

her truth, her faithfulness. Her praise and reward are

in higher hands than mine.”

[Pg 26]

In describing to the Secretary of State certain sanitary

reforms which she carried out in the hospitals of

Scutari, she wrote: “I must pay my tribute to the instinctive

delicacy, the ready attention of orderlies and

patients during all that dreadful period. For my sake

they performed offices of this kind (which they neither

would for the sake of discipline, nor for that of importance

to their own health, which they did not

know), and never was there one word nor one look

which a gentleman would not have used; and while

paying this humble tribute to humble courtesy, the

tears come into my eyes as I think how amidst scenes

of loathsome disease and death, there rose above it all

the innate dignity, gentleness, and chivalry of the

men, shining in the midst of what must be considered

the lowest sinks of human misery, and preventing, instinctively,

the use of one expression which could distress

a gentlewoman.”

It is easy to think of Miss Nightingale as a great

organizer and executive—it is less easy to imagine

how she found time to give the personal attention to

the individual patient that she did give. “She was

wonderful,” said one, “at cheering up any one who was

a bit low.” In the midst of her manifold responsibilities

she found time to write hundreds of letters, to

relatives at home, for those unable to write, and to instill

in the nurses associated with her the same spirit.

There was nothing mechanical in the nursing of that

period. Every patient was a human being with relatives

and anxious friends rightfully interested, who

must be kept informed as to his condition, as far as

possible.

TEACHING A COUNTRY BY DEMONSTRATION.

Nowadays when women of many classes are contending

that legislation is necessary before real reforms

[Pg 27]

can be brought about, it is interesting to note

that Florence Nightingale’s reforms were initiated

mainly by demonstration of the way a thing could be

accomplished. Her biographer, in writing of this,

says that “it was a common belief of the time that it

was in the nature of the British soldier to be drunken.

The same idea was entertained of the British nurse.

Miss Nightingale utterly refused to believe it.” Writing

to a friend, while in Scutari, she remarks: “I have

never been able to join in the popular cry about the

recklessness, sensuality and helplessness of the soldiers.

On the contrary, I should say that I have never

seen so teachable and helpful a class as the army generally.

Give them opportunity, promptly and securely,

to send money home and they will use it. Give them

schools and lectures and they will come to them. Give

them books and games and amusements and they will

leave off drinking. Give them suffering and they will

bear it. Give them work to do and they will do it.”

Acting on this belief, we find Miss Nightingale, in

addition to her work in improving the nursing in the

army, arranging plans by which soldiers might remit

money to their relatives, by forming an extempore

money order office where, on four afternoons each

month, she personally received money from soldiers

and arranged for sending it to relatives in England.

Soon the government took the hint which she thus

gave them—and established money order offices at

different points where the troops were stationed.

Along the same practical line was her effort to

combat the drink habit by establishing a coffee house,

the details of which she arranged. Her next practical

step was the establishment of reading rooms and class

rooms—which were fitted up with textbooks, copy

books, prints, maps, games, etc., secured from personal

[Pg 28]

friends in the home land. On her request, two

schoolmasters were sent out from England to take

charge of “the education of the army.”

Scarcely had she returned from the Crimea than

she began her long campaign for better sanitary conditions

in the army, wherever it might be called in the

future. “We can do no more,” she said, “for those who

have suffered and died in their country’s service; they

need our help no longer; their spirits are with God who

gave them. It remains for us to strive that their sufferings

may not have been endured in vain—to endeavor

so to learn from experience as to lessen such

sufferings in future by forethought and wise management.”

[Pg 29]

“Notes on Hospitals”

Chapter III.

“It may seem a strange principle to enunciate,”

wrote Miss Nightingale in 1863, “as the very first requirement

in a hospital that it should do the sick no

harm. It is quite necessary, nevertheless, to lay down

such a principle, because the actual mortality in hospitals,

especially in those of large crowded cities is

very much higher than any calculation founded on the

mortality of the same class of diseases among patients

out of hospitals would lead us to expect.”

At the time Miss Nightingale returned from the

Crimea, the death rate in hospitals was lamentably

high, and it was but natural that she should turn her

attention to remedying such conditions, or at least to

call attention to them. In 1858 her book, “Notes on

Hospitals,” was issued. A noted man in acknowledging

receipt of a copy stated that it appeared to him to

be the most valuable contribution to sanitary science

in application to medical institutions, that he had ever

seen. In this book we find her calling attention to

overcrowding, lack of drainage under hospitals, to

ventilation, to the necessity of having non-absorbent

floors and walls, to the desirability of iron beds, hair

mattresses, and glass or earthen ware cups, instead of

tin—also to needed improvements in hospital kitchens

and laundries, to the curative effects of light—all of

which ideas are today regarded as essentials in hospitals,

but which were then years in advance of general

practice. It is easy to point out defects—not always

so easy to produce practical plans for correcting them,

but Miss Nightingale not only called attention to the

defects but at the same time showed how to remedy

them. In the second edition of the book she enumerated

“Sixteen Sanitary Defects in the Construction of

[Pg 30]

Hospital Wards”—accompanying each statement with

definite plans for correcting the defect. The publication

of this little book on hospitals brought to her numerous

requests for consultation regarding the construction

of new hospitals which were being planned

and more than a dozen hospitals constructed, soon

after that time, had the benefit of her advice and detailed

consideration of the architect’s plans. The

questions as to the desirability of pavilion construction

and whether a hospital should be built in the midst

of a well-populated section, and among the class of

people it is expected to serve—or in a more distant

location, where better light and air are to be had—which

are still debated among hospital people, were

then as hotly debated as now. It was not unusual to

find her making out the main specifications for an

entire hospital building regarding which her advice

had been sought, and architects and sanitary engineers

were very glad to be able to quote her approval

of their plans. Sir Edward Cook, her biographer,

states that “in its day, Miss Nightingale’s Notes on

Hospitals revolutionized many ideas, and gave a new

direction to hospital construction.”

“NOTES ON NURSING.”

Between the return of Miss Nightingale from the

Crimea, and the starting of the first real training

school for nurses some three or four years elapsed,

which were largely devoted to the securing of better

sanitary conditions for the army—and in tedious and

exhaustive work with military officials and legislators,

in addition to her work in improving hospital buildings

and methods.

During this time, her book, Notes on Nursing, was

issued, in order to deepen the impression she was trying

to make, that nursing skill was not something

[Pg 31]

simply to be “picked up” by any woman, but that it

required special gifts, special training—training by

precept, as well as by example. The book furnished

the precept teaching for that time, and was immensely

popular. It is safe to say that no book on nursing

which has appeared since, or which probably ever will

appear, was received with the enthusiasm, that this

book of hers aroused among all sorts of people, from

the queen down to the laborer’s wife. It many ways,

it was a remarkable book—remarkable in the underlying

principles set forth, now, well understood and accepted,

yet then a new story—and remarkable for its

keen appreciation of the needs of the sick. Nurses of

today, even graduates, might very profitably try to

really learn and practice some of the lessons contained

in that little book, written more than half a century

ago. Her gospel of fresh air, and its application to

health, was a new gospel at that time—yet after all

these years it is still unheeded in many homes.

QUOTATIONS FROM HER “NOTES ON NURSING.”

“Do you ever go into the bedrooms of any persons

of any class, whether they contain one, two or twenty

people, whether they hold sick or well at night, or before

the windows are opened in the morning and ever

find the air anything but unwholesomely close and

foul? And why should it be so? During sleep the

human body even when in health, is far more injured

by the influence of foul air than when awake. Why

can’t you keep the air all night, then, as pure as the air

without in the rooms you sleep in? But for this you

must have sufficient outlet for the impure air you

make yourselves, to go out; and sufficient inlet for the

pure air from without to come in. You must have

open chimneys, open windows or ventilators; no close

[Pg 32]

curtains round your beds; no shutters or curtains to

your windows; none of the contrivances by which you

undermine your own health or destroy the chances of

recovery of the sick.”

“Let no one ever depend upon fumigations, ‘disinfectants,’

and the like for purifying the air. The offensive

thing, not its smell, must be removed. A celebrated

medical lecturer began one day, ‘Fumigations,

gentlemen, are of essential importance. They make

such an abominable smell that they compel you to

open the windows.’”

“True nursing ignores infection except to prevent

it. Cleanliness and fresh air from open windows with

unremitting attention to the patient, are the only defence

a true nurse either needs or asks.”

“The very first canon of nursing, the first and the

last thing upon which a nurse’s attention must be fixed,

the first essential to a patient, without which all the

rest you can do for him is as nothing, with which

I had almost said you may leave all the rest alone, is

this: To keep the air he breathes as pure as the

external air, without chilling him.”

“The time when people take cold (and there are

many ways of taking cold, besides a cold in the nose),

is when they first get up after the two-fold exhaustion

of dressing and of having had the skin relaxed by

many hours, perhaps days, in bed, and thereby rendered

more incapable of reaction. Then the same

temperature which refreshes the patient in bed may

destroy the patient just risen. And common sense will

point out, that, while purity of air is essential, a temperature

must be secured which shall not chill the

patient.”

[Pg 33]

“Of all methods of keeping patients warm the very

worst certainly is to depend for heat on the breath and

bodies of the sick.”

“To be ‘in charge’ is certainly not only to carry

out the proper measures yourself, but to see that every

one else does so too; to see that no one either wilfully

or ignorantly thwarts or prevents such measures. It

is neither to do everything yourself nor to appoint a

number of people to each duty, but to ensure that each

does that duty to which he is appointed.”

“Conciseness and decision are, above all things,

necessary with the sick. Let your thought expressed

to them be concisely and decidedly expressed. What

doubt and hesitation there may be in your own mind

must never be communicated to theirs.”

“‘What can’t be cured must be endured,’ is the very

worst and most dangerous maxim for a nurse which

ever was made. Patience and resignation in her are

but other words for carelessness or indifference—contemptible,

if in regard to herself; culpable, if in regard

to her sick.”

“I would appeal most seriously to all friends, visitors,

and attendants of the sick to leave off this practice

of attempting to ‘cheer’ the sick by making light

of their danger and by exaggerating their probabilities

of recovery.”

“A sick person intensely enjoys hearing of any material

good, any positive or practical success of the

right. He has so much of books and fiction, of principles,

and precepts, and theories; do, instead of advising

him with advice he has heard at least fifty times

[Pg 34]

before, tell him of one benevolent act which has really

succeeded practically,—it is like a day’s health to him.

You have no idea what the craving of sick with undiminished

power of thinking, but little power of doing,

is to hear of good practical action, when they can no

longer partake in it.”

“The most important practical lesson that can be

given to nurses is to teach them what to observe—how

to observe—what symptoms indicate improvement—what

the reverse—which are of importance—which

are of none—which are the evidence of neglect—and

of what kind of neglect. All this is what ought to

make part, and an essential part, of the training of

every nurse.”

“Courts of justice seem to think that anybody can

speak ‘the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,’ if

he does but intend it. It requires many faculties combined

of observation and memory to speak ‘the whole

truth,’ and to say ‘nothing but the truth.’

“‘I knows I fibs dreadful, but believe me, Miss, I

never finds out I has fibbed until they tells me so,’ was

a remark actually made. It is also one of much more

extended application than most people have the least

idea of.”

“There may be four different causes, any of which

will produce the same result, viz., the patient slowly

starving to death from want of nutrition:

- 1. Defect in cooking;

- 2. Defect in choice of diet;

- 3. Defect in choice of hours for taking diet;

- 4. Defect of appetite in patient.

[Pg 35]

Yet all these are generally comprehended in the one

sweeping assertion that the patient has ‘no appetite.’”

“If you cannot get the habit of observation one

way or other, you had better give up the being a nurse,

for it is not your calling, however kind and anxious

you may be.”

“It appears that scarcely any improvement in the

faculty of observing is being made. Vast has been the

increase of knowledge in pathology—that science

which teaches us the final change produced by disease

on the human frame—scarce any in the art of observing

the signs of the change while in progress. Or,

rather, is it not to be feared that observation, as an

essential part of medicine, has been declining?”

“In dwelling upon the vital importance of sound

observation, it must never be lost sight of what observation

is for. It is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous

information or curious facts, but for the

sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort.

The caution may seem useless, but it is quite surprising

how many men (some women do it too), practically

behave as if the scientific end were the only

one in view, or as if the sick body were but a reservoir

for stowing medicines into, and the surgical disease

only a curious case the sufferer has made for the

attendant’s special information.”

“Pathology teaches the harm that disease has

done. But it teaches nothing more. We know nothing

of the principle of health, the positive of which

pathology is the negative, except from observation and

experience. And nothing but observation and experience

will teach us the ways to maintain or to bring

back the state of health.”

[Pg 36]

“Unnecessary noise, then, is the most cruel absence

of care which can be inflicted on the sick or well.

Unnecessary (although slight) noise injures a sick

person much more than necessary noise, of a much

greater amount. A good nurse will always make sure

that no door or window in her patient’s room shall

rattle or creak; that no blind or curtain shall, by any

change of wind through the open window, be made to

flap. If you wait till your patients tell you of these

things, where is the use of their having a nurse.”

“Always sit within the patient’s view, so that when

you speak to him he has not painfully to turn his head

round in order to look at you. Everybody involuntarily

looks at the person speaking. If you make this act a

wearisome one on the part of the patient, you are

doing him harm.”

“Volumes are now written and spoken upon the

effect of the mind upon the body. Much of it is true.

But I wish a little more was thought of the effect of

the body on the mind. * * * A patient can just as

much move his leg when it is fractured, as change his

thoughts when no external help from variety is given

him. * * * It is an ever-recurring wonder to see

educated people who call themselves nurses, acting

thus. They vary their own objects, their own employments,

many times a day; and while nursing (?) some

bedridden sufferer they let him lie there staring at a

dead wall, without any change of object to enable him

to vary his thoughts; and it never occurs to them, at

least to move his bed so that he can look out of the

window.”

“It is often thought that medicine is the curative

process. It is no such thing; medicine is the surgery

of functions, as surgery proper is that of limbs and

[Pg 37]

organs. Neither can do anything but remove obstructions;

neither can cure. Nature alone cures.”

“A celebrated man has told us that one of the main

objects in the education of his son, was to give him a

ready habit of accurate observation, a certainty of perception

and that for this purpose one of his means was

a month’s course as follows: He took the boy rapidly

past a toy-shop; the father and son then described to

each other as many of the objects as they could, which

they had seen in passing the windows, noting them

down with pencil and paper and returning afterward

to verify their own accuracy. I have often thought

how wise a piece of education this would be for higher

objects; and in our calling of nurses the thing itself is

essential. For it may safely be said not that the habit

of ready and correct observation will by itself make

us useful nurses, but that without it we shall be useless

with all our devotion.”

“It seems a commonly received idea among men

and even among women themselves that it requires

nothing but a disappointment in love, the want of an

object, a general disgust, or incapacity for other things,

to turn a woman into a good nurse. This reminds

one of the parish where a stupid old man was sent to

be schoolmaster because he ‘was past keeping the

pigs’.”

“And remember every nurse should be one who is

to be depended upon, in other words, capable of being

a ‘confidential’ nurse. She does not know how soon

she may find herself placed in such a situation; she

must be no gossip, no vain talker; she should never

answer questions about her sick except to those who

have a right to ask them; she must, I need not say, be

strictly sober, and honest; but more than this, she

[Pg 38]

must be a religious and devoted woman; she must

have a respect for her own calling because God’s

precious gift of life is often literally placed in her

hands; she must be a sound and close and quick

observer; and she must be a woman of delicate and

decent feeling.”

“The everyday management of a large ward let

alone of a hospital—the knowing what are the laws of

life and death for men and what the laws of health for

wards—are not these matters of sufficient importance

and difficulty to require learning by experience and

careful inquiry, just as much as any other art? They

do not come by inspiration to the lady disappointed in

love, nor to the poor workhouse drudge hard up for a

livelihood.”

“To revert to children. They are much more susceptible

than grown people to all noxious influences.

They are affected by the same things, but much more

quickly and seriously, viz., by want of fresh air, or

proper warmth, want of cleanliness, in house clothes,

bedding or body, by startling noises, improper food, or

want of punctuality; by dulness and by want of light;

by too much or too little covering in bed; or when up,

by want of the spirit of management generally in those

in charge of them. One can therefore, only press the

importance, as being yet greater in the case of children,

greatest in the case of sick children, of attending

to these things.”

[Pg 39]

The Nightingale Training School

For Nurses

Chapter IV.

Deep as was the desire of Miss Nightingale to institute

plans for the training of hospital nurses, her

health, after her return from the army service, was so

impaired, that to undertake the task herself was impossible.

The fund of $250,000 had been placed in

charge of a board of trustees and invested for the

purpose of establishing a school of which she expected

to be the superintendent. Her health, however, grew

worse rather than better, and after two years had

passed, she wrote to the Chairman of the Council of

the Nightingale Fund, of her inability to carry out the

plans. It became necessary to find other persons

through whom she might work, without having to

carry the everyday details. Her choice fell on St.

Thomas’ Hospital—largely because “the matron of

the hospital, Mrs. Wardroper, was a woman after Miss

Nightingale’s own heart, strong, devoted to her work,

devoid of all self-seeking, full of decision and administrative

ability.” Of this remarkable woman, Mrs.

Wardroper, who for twenty-seven years was superintendent

of the Nightingale School, Miss Nightingale

has left a character sketch:

[A]“I saw her,” she says, “first, in October, 1854,

when the expedition of nurses was sent to the Crimean

war. She had been then nine months matron of the

great hospital in London, of which for 33 years, she

remained head, and reformer of nursing. Training was

then unknown; the only nurse worthy of the name

that could be given to the expedition was a ‘Sister’ who

had been pensioned some time before and who proved

invaluable. I saw her next after the conclusion of the

war. She had already made her mark; she had weeded

[Pg 40]

out the inefficient, morally and technically; she had

obtained better women as nurses; she had put her

finger on some of the most flagrant blots, such as the

night nursing, and where she laid her finger, the blot

was diminished as far as possible, but no training had

yet been thought of.

“Her power of organization, her courage and discrimination

in character, were alike remarkable. She

was straightforward, true, upright. She was decided.

Her judgment of character came by intuition, at a

flash, not by much weighing and consideration. Yet

she rarely made a mistake, and she would take the

greatest pains in her written delineations of character

required for record, writing them again and again in

order to be perfectly just. She was free from self-consciousness;

nothing artificial about her. She did

nothing, and abstained from nothing because she was

being looked at. Her whole heart and mind were in

the work she had undertaken.

“She was left a widow at 42 with a young family.

She had never had any training in hospital life for

there was none to be had. Her force of character was

extraordinary. Her word was law. * * * She

knew what she wanted and did it. She was a strict

disciplinarian; very kind, often affectionate rather

than loving. * * * She was a thorough gentle-woman,

nothing mean or low about her; magnanimous

and generous rather than courteous. All this was

done quietly. She had a hard life but never proclaimed

it. What she did was done silently.”

Such was Miss Nightingale’s estimate of the first

superintendent of a training school for nurses organized

according to her own ideas. Mrs. Wardroper retired

in 1887 and died in 1892. The plans for the training

school were of Miss Nightingale’s making—the

[Pg 41]

carrying of them out devolved almost wholly on Mrs.

Wardroper, and on the Resident Medical Officer of the

hospital, R. G. Whitfield.

There were two essential principles to the plan:

The nurses were to have their technical training in

hospitals specially organized for the purpose. They

should live in a home fit to form their moral life and

discipline. Plans for lectures were carefully made and

carried out, and a “Monthly Sheet of Personal Character

and Acquirements” of each nurse was arranged

by Miss Nightingale herself, for the Matron to fill in.

The character record was to be noted under five heads:

punctuality, quietness, trustworthiness, personal neatness

and cleanliness, and ward management.

The records in regard to nursing technique were

made out on forms carefully prepared by Miss Nightingale

under numerous headings, with copious subheadings.

At her request, the Resident Medical Officer

prepared a form of General Directions which were to

aid the nurses in taking notes of the medical and surgical

cases in the hospitals.

The school opened June 24th, 1860. The course of

training was to extend over one year. The writer has

in her possession a copy of the first set of “Rules and

Regulations for Probationers Under the Nightingale

Fund”—and they bear a close resemblance to regulations

in force today. She laid foundations which have

stood the test of time.

In the first report of the Committee in charge of

the training school, one finds the details of the qualifications

expected, set forth as follows, with the added

statement that all important details for the working of

the plan have been suggested by Miss Nightingale, or

submitted to her for approval:

[Pg 42]

“DUTIES OF PROBATIONERS UNDER THE

NIGHTINGALE FUND.”

You are required to be

Sober

Honest

Truthful

Punctual

Quiet and Orderly

Cleanly and Neat.

You are expected to become skilful in—

1. In the dressing of blisters, burns, sores,

wounds, and in applying fomentations, poultices, and

minor dressings.

2. In the application of leeches, externally and

internally.

3. In the administration of enemas for men and

women.

4. In the management of trusses and appliances

in uterine complaints.

5. In the best method of friction to the body and

extremities.

6. In the management of helpless patients, i.e.,

moving, changing, personal cleanliness, of feeding,

keeping warm (or cool), preventing and dressing bedsores,

managing position of.

7. In bandaging, making bandages and rollers,

lining of splints, etc.

8. In making the beds of patients, and removal of

sheets whilst patient is in bed.

9. You are required to attend at operations.

10. To be competent to cook gruel, arrowroot,

eggflip, puddings, drinks for the sick.

[Pg 43]

11. To understand ventilation, or keeping the

ward fresh by night as well as by day; you are to be

careful that great cleanliness is observed in all the

utensils; those used for the secretions as well as those

required for cooking.

12. To make strict observation of the sick in the

following particulars:

The state of secretions, expectorations, pulse, skin,

appetite; intelligence, as delirium or stupor; breathing,

sleep, state of wounds, eruptions, formation of matter;

effect of diet or of stimulants, and of medicine.

13. And to learn the management of convalescents.

IDEALS OF TRAINING.

Her ideals of training, what she hoped training

might accomplish, are embodied, in part at least, in

the following quotations from her writings at a later

period.

What is training? Training is to teach the nurse

to help the patient to live. Nursing the sick is an

art and an art requiring an organized practical and

scientific training; for nursing is the skilled servant of

medicine, surgery and hygiene. A good nurse of

twenty years ago had not to do the twentieth part of

what she is required by her physician or surgeon to do

now; and so after the year’s training she must be still

training under instruction in her first and even second

year’s hospital service. The physician prescribes for

supplying the vital force, but the nurse supplies it.

Training is to teach the nurse how God makes

health and how He makes disease.

Training is to teach a nurse to know her business,

that is to observe exactly in such stupendous issues as

life and death, health and disease.

[Pg 44]

Training has to make her not servile, but loyal to

medical orders and without the independent sense or

energy of responsibility which alone secures real

trustworthiness.

Training is to teach the nurse how to handle the

agencies within our control which restore health and

life, in strict intelligent obedience to the physician’s

or surgeon’s power and knowledge, how to keep the

health mechanism prescribed to her in gear.

Training must show her how the effects on life of

nursing may be calculated with nice precision, such

care or carelessness, such a sick rate, such a duration

of case, such a death rate.

In 1871, St. Thomas’ Hospital removed to the

large new buildings in its present location near the

Houses of Parliament, London, and with the occupation

of the new building, the number of nurses and

probationers in the Nightingale School greatly increased.

New problems in management were created

and Miss Nightingale feared that her high ideals for

the nurses were not being realized as fully as she desired.

Her health having improved, she determined on

a closer supervision of the school, by herself. One

result of this supervision, as she herself afterward

stated, was that “the training school became a Home—a

place of moral, religious and practical training—a

place of training character, habits, and intelligence,

as well as of acquiring knowledge.” She knew as

much, probably, as any hospital superintendent knows

today, of the problem of securing the right kind of

young women to be trained, and she was fully convinced

that a good nurse must be first of all a good

woman. When applications came to her from smaller

cities and towns for trained nurses to take charge of

the nursing, she was accustomed to reply, “Have you

sent me any probationers? I can’t stamp material out

of the ground.”

[Pg 45]

Her character sketches, as preserved among her

papers, of some of the probationers she had to deal

with in those days, show her keen insight into human

nature. “Miss A. Tittupy, flippant, pretension-y, veil

down, ambitious, clever, not much feeling, talk-y,

underbred, no religion, may be persevering from ambition

to excel but takes the thing up as an adventure.”

“Nurse B. A good little thing, spirited, too much

friends with G., shares in her flirtations.” “Miss X.

More cleverness than judgment, more activity than

order, more hard sense than feeling, never any high

view of her calling, always thinking more of appearances

than of the truth, more flippant than witty, more

petulance than vigor.” These are typical of her notes

written after personal conversation with different probationers.

The great necessity of some such notes is

shown in the enormous demand that had been created

for trained nurses for other hospitals—to fill responsible

positions where they would have the choosing and

training of other nurses. These demands came to her

unceasingly in the earlier years of trained nursing.

Through her influence an assistant superintendent

of the Nightingale training school had been appointed

to whom was given the title of Home Sister. The

duties of the Home Sister were varied, but among

other things she was expected to supplement the lectures

and bedside teaching and demonstration by regular

classes. She was also to “encourage general

reading, to arrange Bible classes, to give wider interests

to the nurses,” in order, as Miss Nightingale said,

to keep them above the mere scramble for a remunerative

place. She regarded the influence of the Home

Sister on the moral and spiritual side of the school as

more important than her technical instruction.

It is stated that the besetting sin of the Nightingale

Nurses in those earlier days was self-sufficiency.

[Pg 46]

“They knew,” says a writer, “that their training school

was the first of its kind, and they were apt to give

themselves airs.” This tendency in them was vigorously

combated by Miss Nightingale. The picking and

choosing of places or cases in order to select the one

which afforded the prospects of an easy time, she

especially condemned.

“Our brains are pretty nearly useless,” she said, in

one of her annual addresses to the nurses, “if we only

think of what we want and should like ourselves; and

not of what posts are wanting us, or what our posts

are wanting in us. What would you think of a soldier

who, if he were put on duty in the honorable post of

difficulty, as sentry, may be, in the face of the enemy

(and we nurses are always in the face of the enemy,

always in the life and death of our patients)—were to

answer his commanding officer, ‘No, he had rather

mount guard at the barracks or study musketry;’ or

if he had to go as pioneer, or on a forlorn hope, were

to say, ‘no that don’t suit my turn’.”

It was her custom for some years to issue an annual

address to the nurses of the Nightingale School,

and for many years the authorities of the school insisted

on every probationer studying the first of these

addresses, issued in 1872, the year in which she began

her closer supervision of the details of training. In

these addresses she dwelt strongly on the ideals of

nursing she had from the beginning—that it requires

a strong sense of vocation or a special call; that it

needs a religious basis; that it is an art; that there

must be constant progress or stagnation; that the

nurse should be extremely careful of her moral influence.

She had no use for the woman who thought

she was making a sacrifice in taking up nursing; nor

for the woman who thought any kind of service which

had to do with nursing was beneath her—neither had

[Pg 47]

she any patience with the sentimental “ministering

angel” type of nurse. “If we have not true religious

feeling and purpose,” she said in one of her addresses,

“hospital life, the highest of all things with these

becomes without them, a mere routine and bustle and

a very hardening routine and bustle.”

No one who studies Miss Nightingale’s life and

ideals can be left in doubt, that, in her mind, in the

choice of nurses, the first and greatest thing to be considered

was the character of the applicant. She did

not undervalue education but she believed that the

spirit of the woman was of supreme importance.

It is absolutely certain that it was not her medical

or surgical knowledge, (though this was in advance of

the times) that accounted for the remarkable and enduring

influence which she exerted, and is still exerting—even

though we may seem to have shifted the

emphasis from some things which to her were of tremendous

importance, and placed it on other things

which, to her mind, were of secondary consideration.

It is an interesting exercise to analyze the varying

qualities in her great and beautiful life which still

exerts its influence on countless other lives. But after

all, the secret of her success must be summed up in

that combination of qualities, that subtle something

which we call Personality. Her studious avoidance of

honors of all kinds, her purity of motive, the absolute

lack of self-seeking, of honor, prestige or profit for

herself, her courage, tact and quiet perseverance are

qualities on which nurses of the twentieth century

may wisely meditate. Nothing is more needed among

nurses today, than that her spirit, her ideals of life and

character, may be perpetuated. Few of us can render

any greater service to our generation than to exert

ourselves to keep her spirit alive in the nursing profession.

[Pg 48]

Author’s note.—For many of the facts, which form

the foundation of this sketch, the author is indebted

to the authorized biography entitled “The Life of

Florence Nightingale,” by Sir Edward Cook, published

in two volumes by the McMillan Co., 1913. Quotations

have been made from clippings, in several instances, in

which the name of the journal in which they first appeared