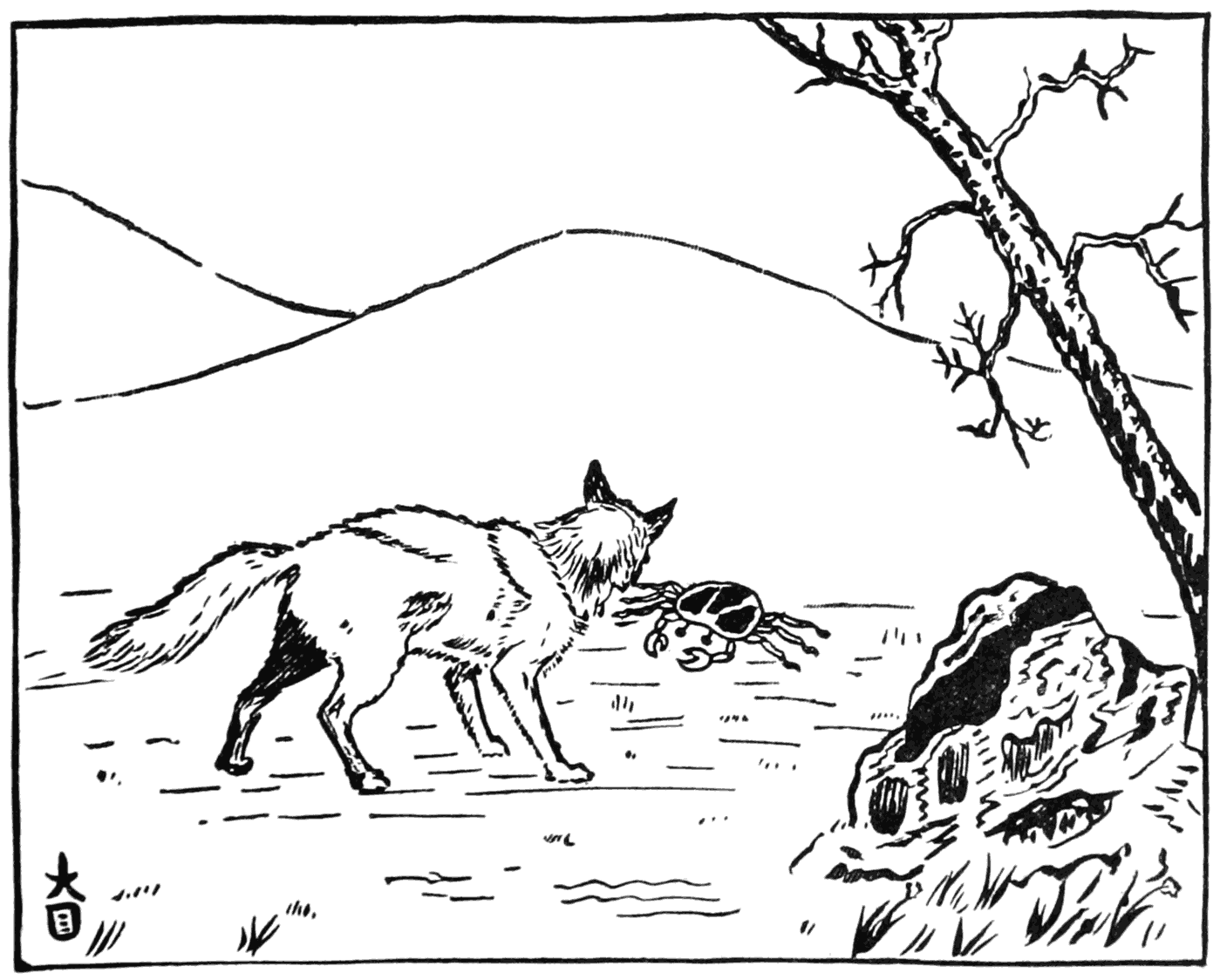

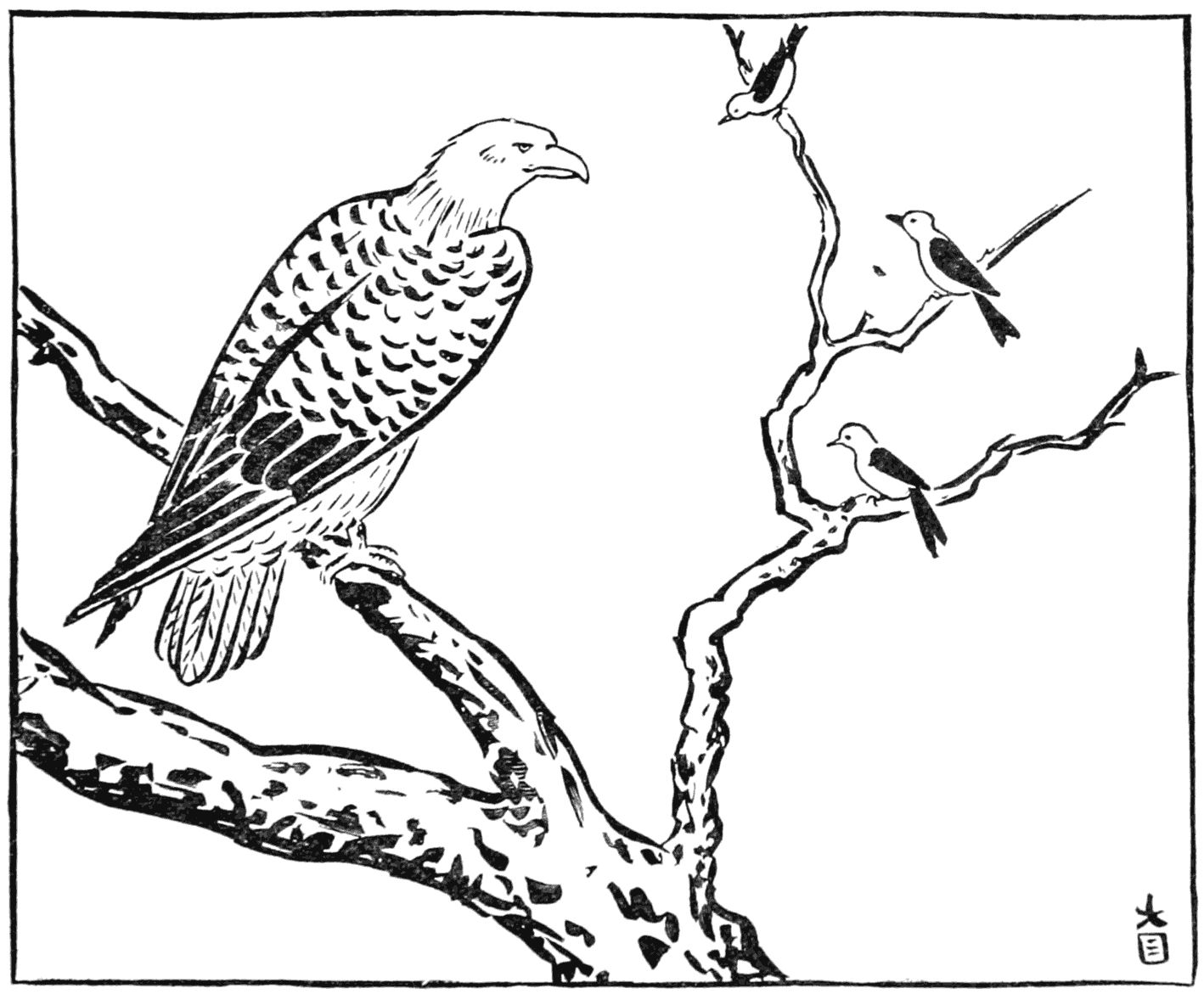

CHINESE FABLES

AND

FOLK STORIES

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1908, by AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London Copyright, 1908, Tokyo

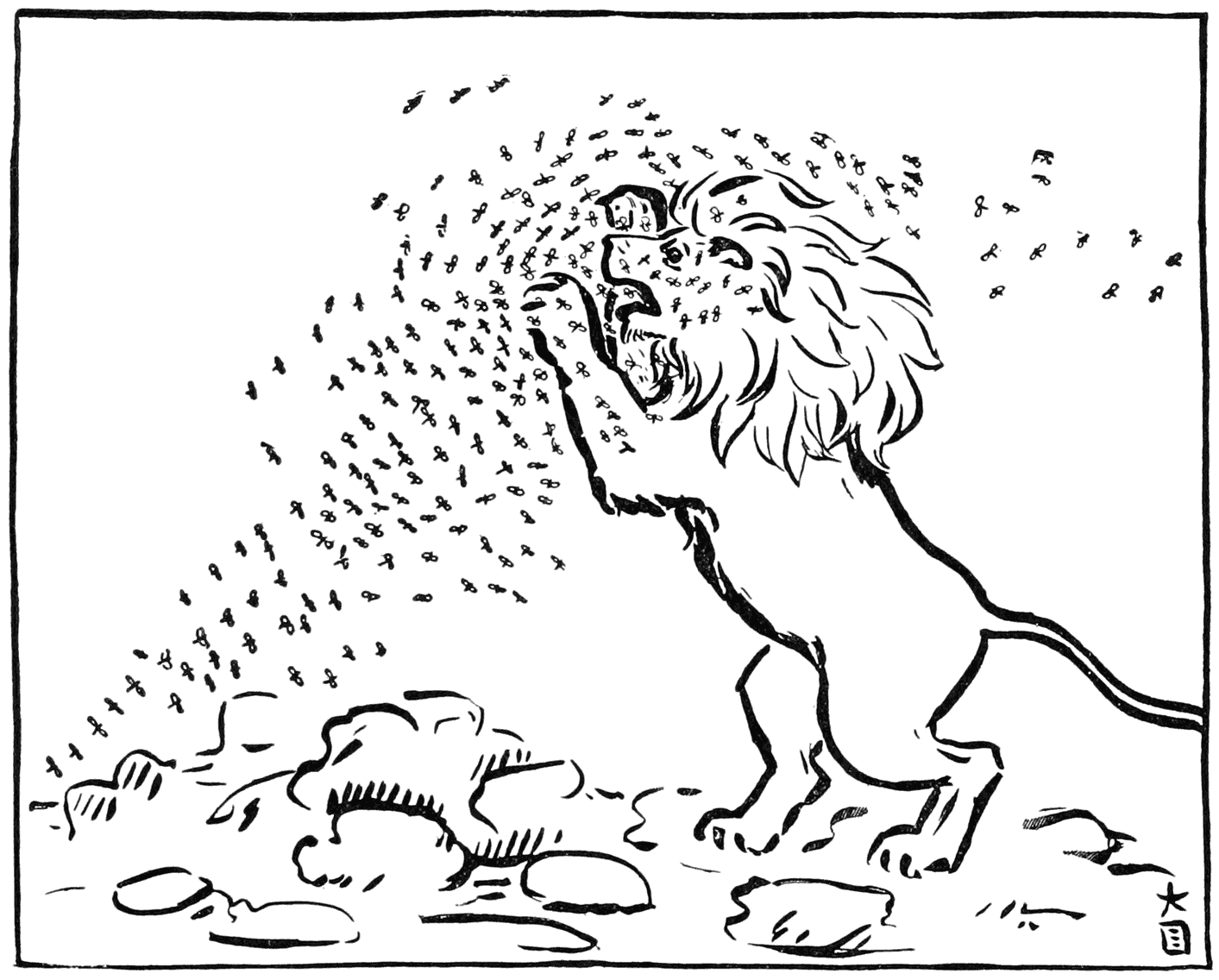

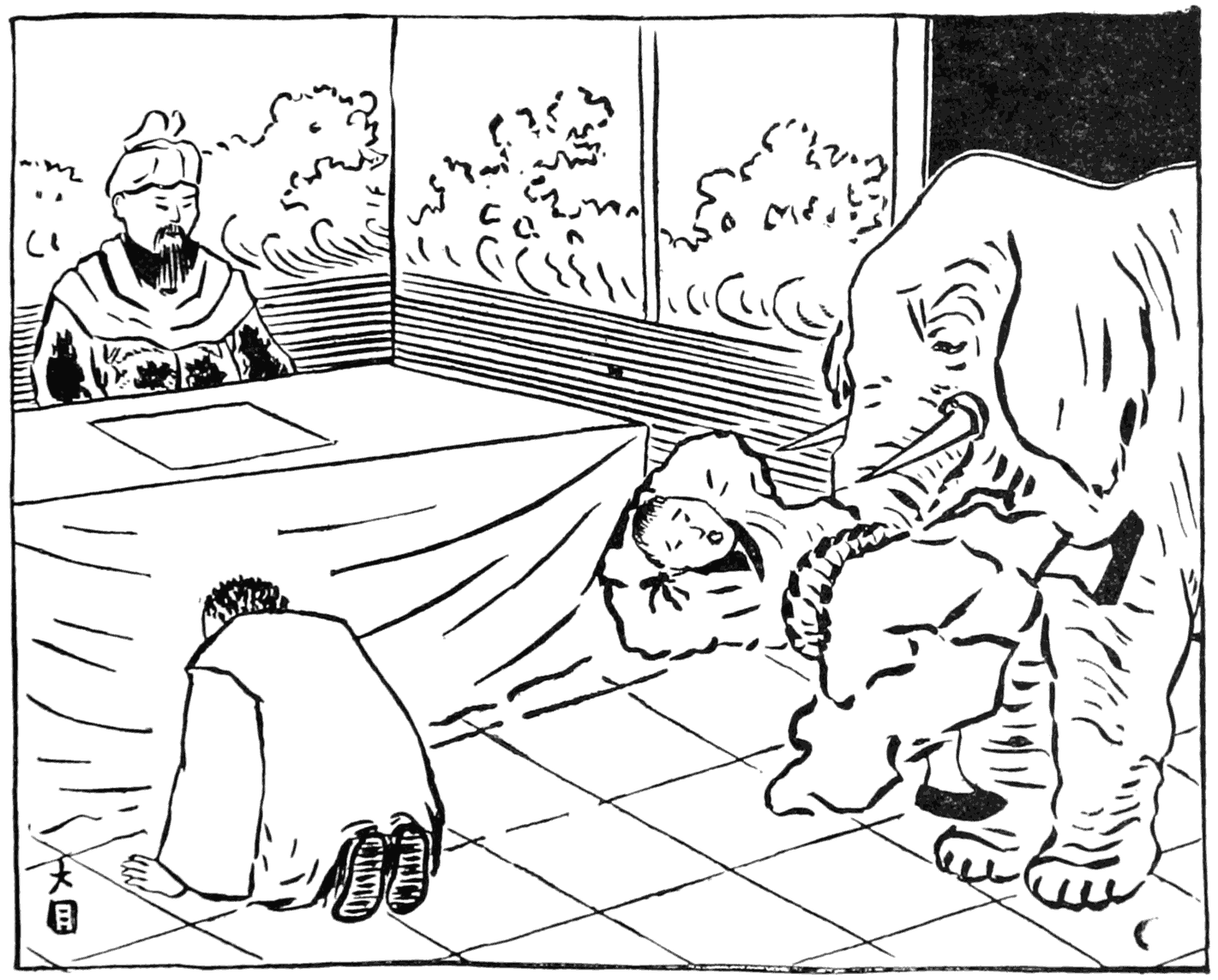

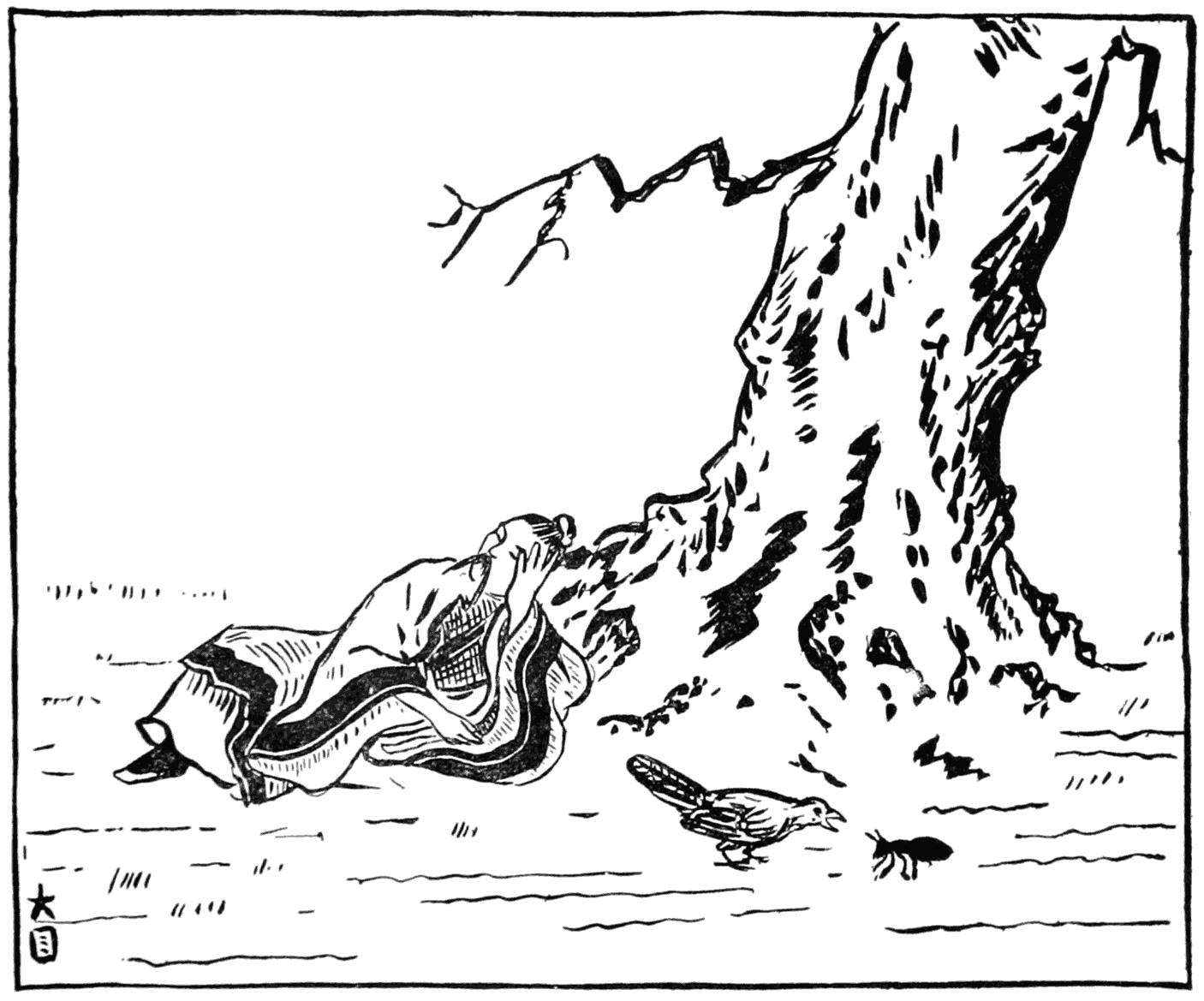

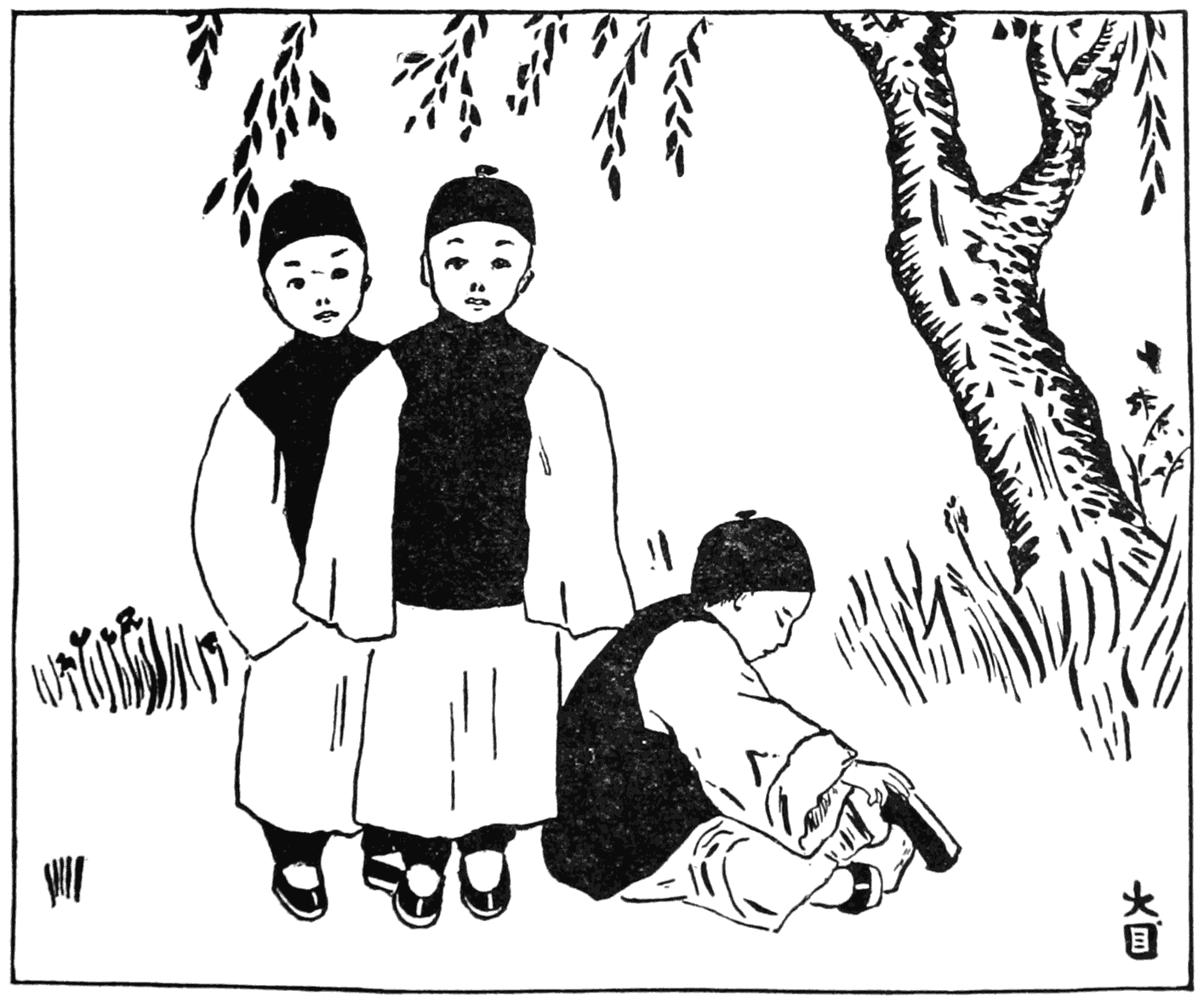

Chinese Fables

W. P. 13

PREFACE

It requires much study of the Oriental mind to catch even brief glimpses of the secret of its mysterious charm. An open mind and the wisdom of great sympathy are conditions essential to making it at all possible.

Contemplative, gentle, and metaphysical in their habit of thought, the Chinese have reflected profoundly and worked out many riddles of the universe in ways peculiarly their own. Realization of the value and need to us of a more definite knowledge of the mental processes of our Oriental brothers, increases wonderfully as one begins to comprehend the richness, depth, and beauty of their thought, ripened as it is by the hidden processes of evolution throughout the ages.

To obtain literal translations from the mental store-house of the Chinese has not been found easy of accomplishment; but it is a more difficult, and a most elusive task to attempt to translate their fancies, to see life itself as it appears from the Chinese point of view, and to retell these impressions without losing quite all of their color and charm.

The “impressions,” the “airy shapes” formed by the Oriental imagination, the life touches and secret [6]graces of its fancy are at once the joy and despair of the one who attempts to record them.

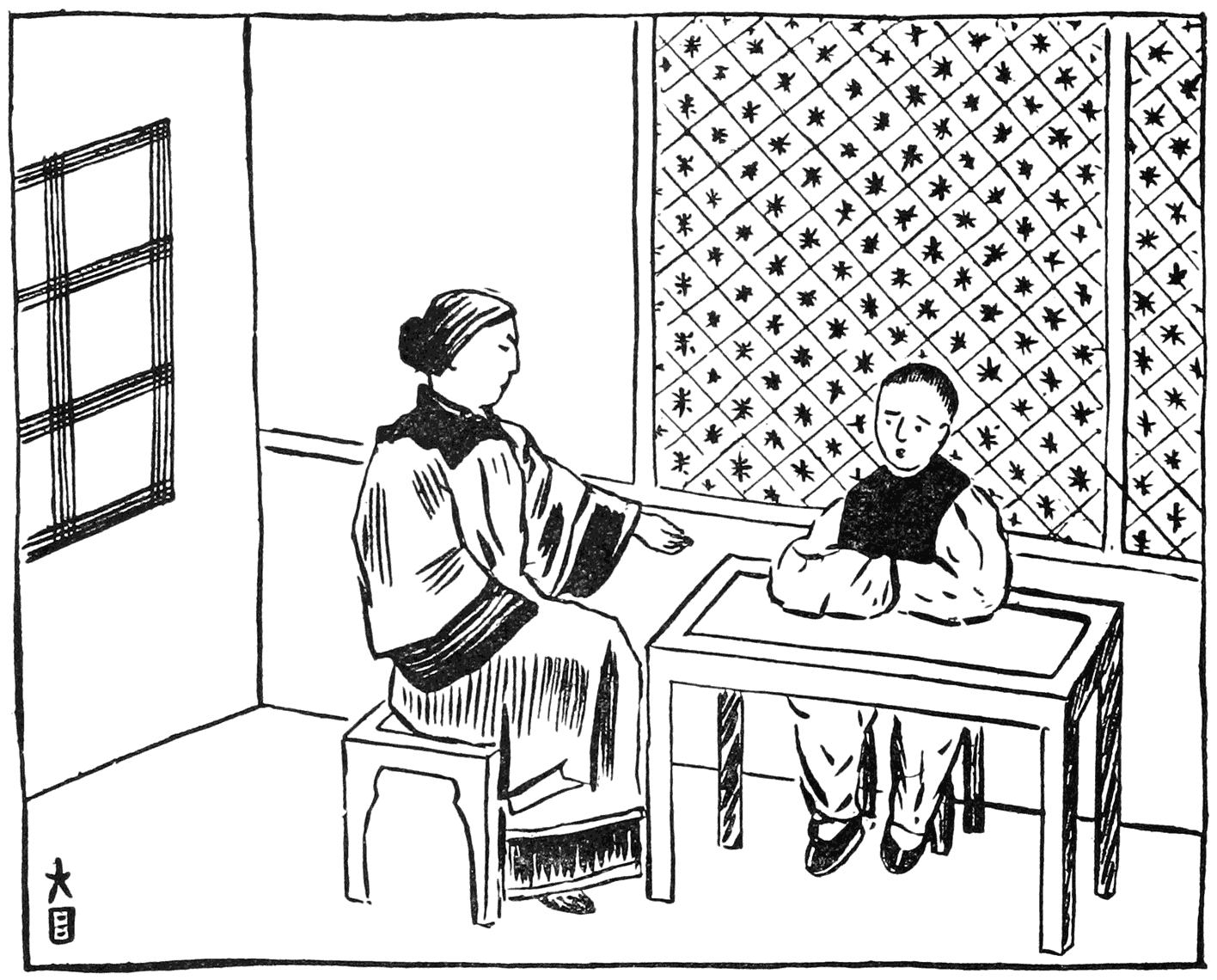

In retelling these Chinese stories of home and school life, the writer has been greatly aided by the Rev. Chow Leung, whose evident desire to serve his native land and have the lives of his people reflected truly, has made him an invaluable collaborator. With the patient courtesy characteristic of the Chinese, he has given much time to explaining obscure points and answering questions innumerable.

It has been an accepted belief of the world’s best scholars that Chinese literature did not possess the fable, and chapters in interesting books have been written on this subject affirming its absence. Nevertheless, while studying the people, language, and literature of China it was the great pleasure of the writer to discover that the Chinese have many fables, a few of which are published in this book.

As these stories, familiar in the home and school life of the children of China, show different phases of the character of a people in the very processes of formation, it is earnestly hoped that this English presentation of them will help a little toward a better understanding and appreciation of Chinese character as a whole.

MARY HAYES DAVIS. [7]

INTRODUCTION

To begin with, let me say that this is the first book of Chinese stories ever printed in English that will bring the Western people to the knowledge of some of our fables, which have never been heretofore known to the world. In this introduction, however, I shall only mention a few facts as to why the Chinese fables, before this book was produced, were never found in any of the European languages.

First of all, our fables were written here and there in the advanced literature, in the historical books, and in the poems, which are not all read by every literary man except the widely and deeply educated literati.

Secondly, all the Chinese books, except those which were provided by missionaries for religious purposes, are in our book language, which is by no means alike to our spoken language. For this reason, I shall be excused to say that it is impossible for any foreigner in China to find the Chinese fables. In fact, there has never been a foreigner in our country who was able to write or to read our advanced books with a thorough understanding. A few of our foreign friends can read [8]some of our easy literature, such as newspapers, but even that sort of literature they are unable to write without the assistance of their native teachers. These are facts which have not, as yet, become known to the Western people who know not the peculiarity of our language—its difficulty.

This book of fables is not of course intended to give a full idea of the Chinese literature, but it shows the thinking reader a bird’s-eye view of the Chinese thought in this form of literature. Furthermore, so far as I know, this book being the first of its kind, will tell the world of the new discovery of the Chinese fables.

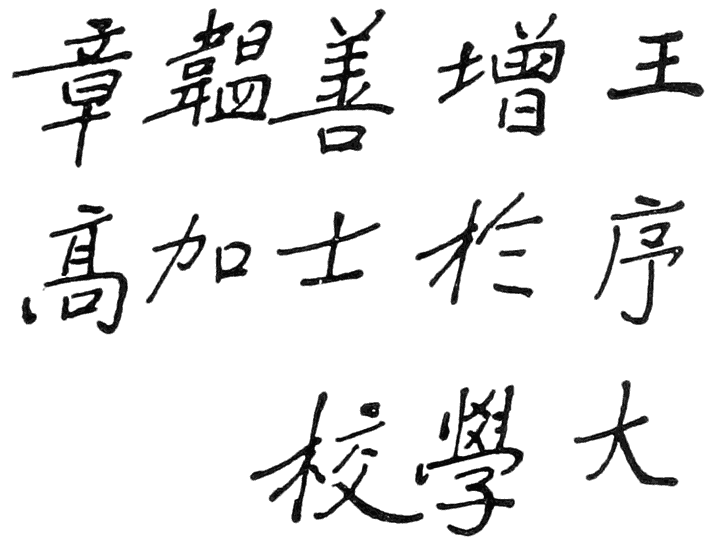

YIN-CHWANG WANG TSEN-ZAN.

The University of Chicago,

Chicago, Ill., U. S. A.

王增善韞章

序拦士加髙

大學校

[9]

CONTENTS

[13]