By

W. J. LOFTIE B.A.; F.S.A.

LONDON

SEELEY AND CO. LIMITED,

ESSEX STREET, STRAND

NEW YORK: MACMILLAN AND CO.

1895

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PLATES | ||

| PAGE | ||

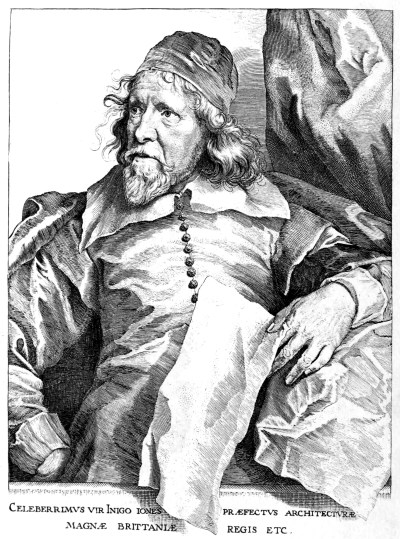

| Inigo Jones. | From the Engraving by Van Voerst, after Van Dyck | Frontispiece |

| Apotheosis of James I. | From the Engraving by S. Gribelin, after Rubens | to face 32 |

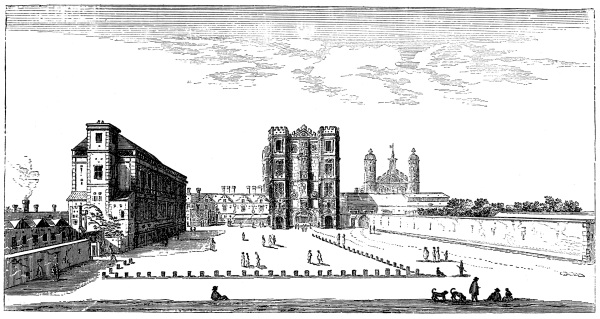

| Whitehall in 1724. | From the Engraving by J. Kip | ” 68 |

| Scotland Yard. | From an Engraving by E. Rooker, | |

| after Paul Sandby, R.A. | ” 72 | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT | |

| PAGE | |

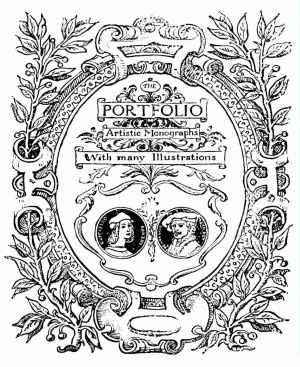

| Banqueting Hall, Holbein’s Gate, and Treasury. | |

| From the Engraving by J. Silvestre, 1640 | 11 |

| Holbein’s Gate. From the Engraving by G. Vertue, 1725 | 14 |

| Whitehall, from King Street. From a Drawing by | |

| T. Sandby, R.A. Engraved by R. Godfrey, 1775 | 17 |

| Whitehall. From an Engraving after a Drawing by | |

| Hollar in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge | 19 |

| The King Street Gate. From the Engraving by G. Vertue, 1725 | 23 |

| Detail of Banqueting House. From Kent’s “Inigo Jones” | 28 |

| Detail of Banqueting House. From Kent’s “Inigo Jones” | 29 |

| Section of the Banqueting House. From Kent’s “Inigo Jones” | 31 |

| Plan of Whitehall. Engraved by G. Vertue, | |

| from a Survey made in 1680 | 33 |

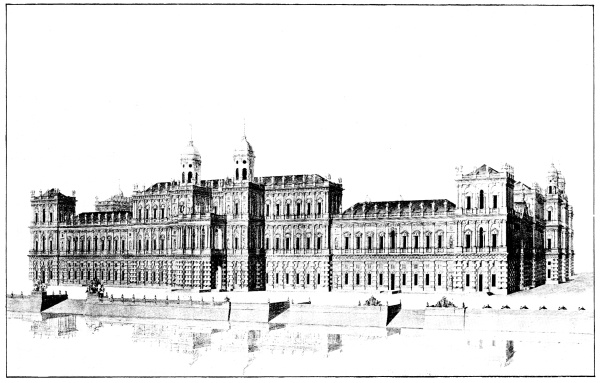

| First Design by Inigo Jones for the rebuilding of Whitehall. | |

| Waterside Front. From Müller | 35 |

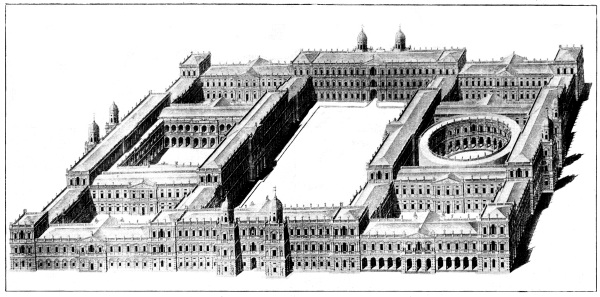

| First Design by Inigo Jones for the rebuilding of Whitehall. | |

| Bird’s-eye View. From Müller | 37 |

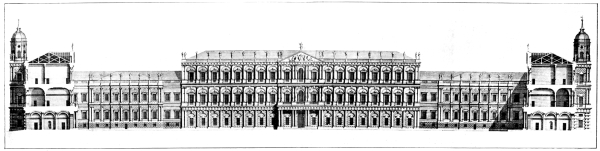

| Part of the First Design by Inigo Jones for the rebuilding | |

| of Whitehall. From Kent’s “Inigo Jones” | 40 |

| Part of the Second Design by Inigo Jones for the rebuilding | |

| of Whitehall. From Campbell’s “Vitruvius Britannicus” | 40 |

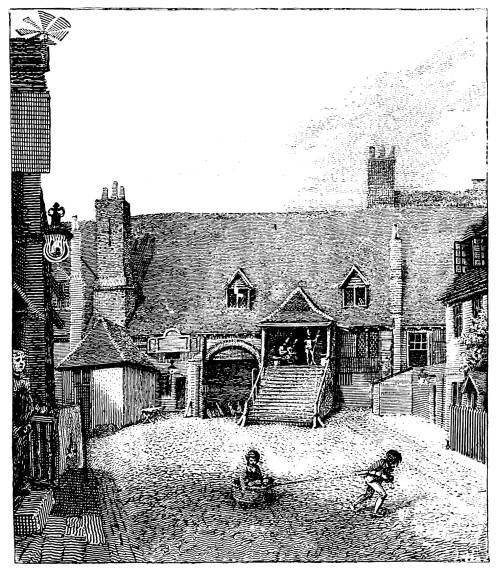

| The Guardroom, Scotland Yard. | |

| From an Etching by J. T. Smith, 1805 | 46 |

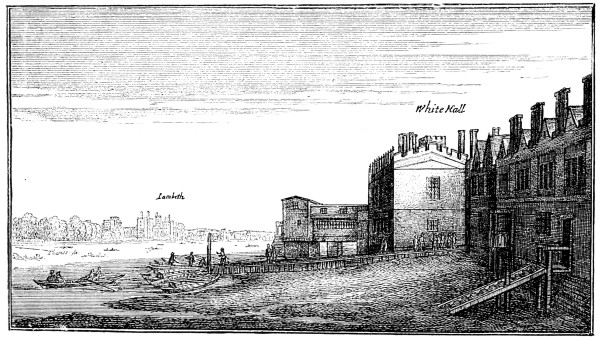

| Lambeth and Whitehall. From the Engraving by W. Hollar | 52 |

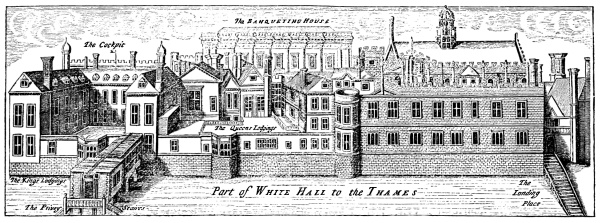

| Whitehall, from the River. From Ogilvy’s Map, 1677 | 54 |

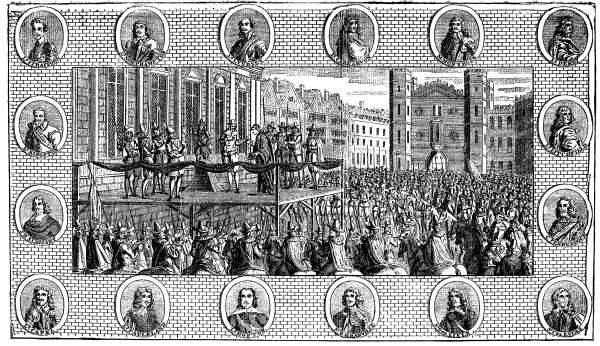

| The Execution of Charles I. From a Print of 1649 | 59 |

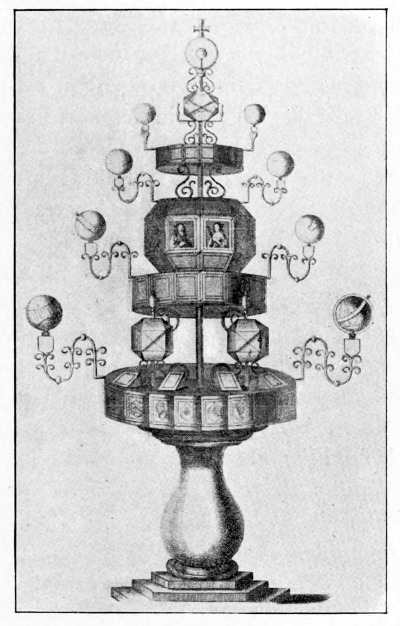

| Pyramidal Dial in Privy Garden, set up in 1669. | |

| From an Engraving by H. Steel, 1673 | 67 |

| Funeral of Queen Mary, 1694. From an Engraving by P. Persoy | 71 |

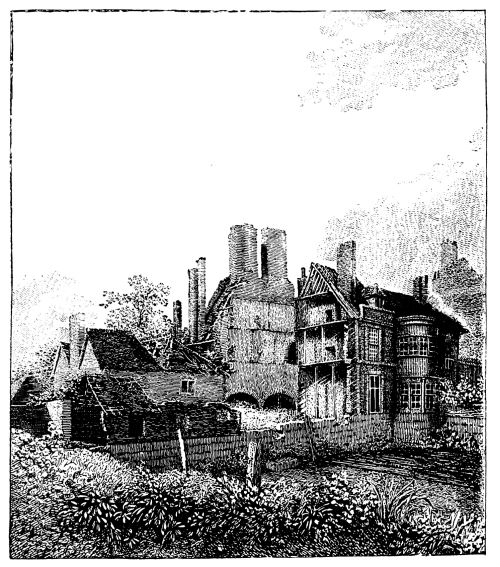

| Part of the Old Palace of Whitehall. | |

| From an Etching by J. T. Smith, 1805 | 73 |

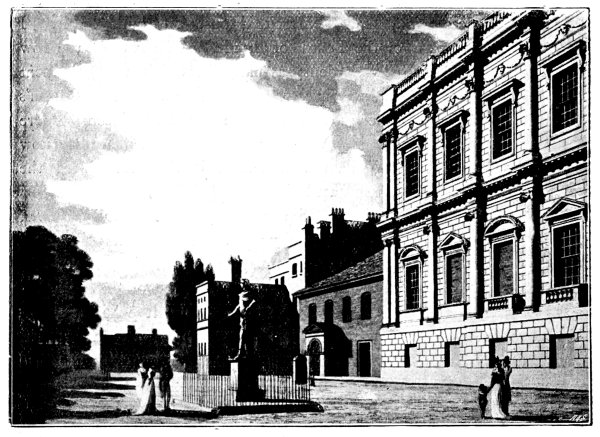

| View in Privy Garden. From an Engraving by J. Malcolm, 1807 | 74 |

| Privy Garden. From an Engraving by T. Malton, 1795 | 76 |

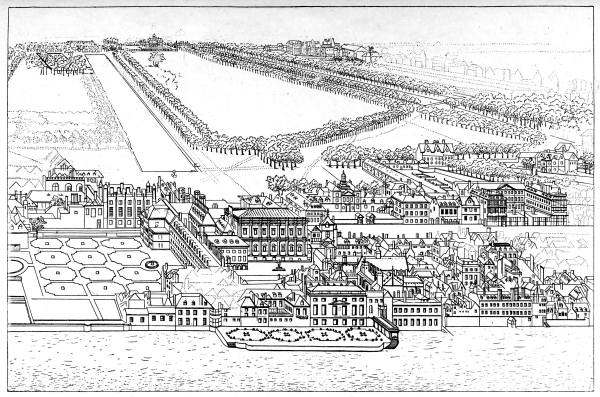

| Bird’s-eye View of Whitehall and St. James’s Park. | |

| From Smith’s “Views of Westminster” | 77 |

Site of Whitehall in the Twelfth Century—Part of Westminster—Hubert de Burgh—York House— Wolsey—Hentzner—Henry VIII.—His Honour of Westminster—Holbein’s Gate—Anne of Cleves— Funeral of Henry VIII.

When Abbot Laurence, of Westminster, looked out to the northward or north-eastward, he could see no land—as far as the wall of London—which did not belong to him and his house. This was the Abbot who first had leave to assume the mitre, and in 1163 he obtained from Pope Alexander II. the canonisation of Edward the Confessor. When worshippers wished to kneel at the new saint’s shrine they had to reach Westminster as best they could. Some, especially those who lived at Charing, or further up the hill, in what was afterwards Hedge Lane, would make their way to the Thames, the best highway in those days. In some seasons, perhaps, the water-courses, which had their origin in the Tyburn, might be dry enough to let them pass, but there were as yet no regular roads and no bridges. One of these water-courses supplied the Abbey, and one ran out where Richmond Terrace is now. We have two documents from which to draw a picture of the ground which was not yet Whitehall. First, we have the evidence afforded by the geographical features of the locality; and, secondly, we have the report of a trial which took place some sixty years ago, when, no doubt, all possible charters and grants and leases and demises were cited. The trial was between the people of Westminster and the people who lived in Richmond [Pg 6] Terrace. Westminster claimed that the Terrace was within the boundaries of St. Margaret. The Terrace claimed that it was extra-parochial, as being on part of the site of the palace of Whitehall. The counsel for Westminster was able to show that Whitehall had been private property before the reign of Henry VIII., and that neither he nor any one else had made it extra-parochial. The verdict, therefore, was in favour of the parishioners of St. Margaret.

We may return to this interesting and instructive report, with its wealth of ancient evidence, and interrogate that much more ancient document, the face of the country. Strange to say, a great deal of that country remains as it was in, say, the reign of Henry III. The green fields and the water-courses are there, though the Abbot in 1250 could no longer look across his own land all the way from Westminster. The divided Tyburn wandered over the green expanse, untroubled with bridges. Two or three small brooks formed here a kind of delta. On the south, one of them ran through Westminster Abbey and divided Thorney Island from Tot Hill. Another ran through the district we call Whitehall. The land between was low and marshy, and even at the present day, when there has been so much levelling up, the statue of Charles I. is upon ground ten feet higher than Parliament Street. If, standing on the future site of Whitehall we looked to the westward, we saw nothing but a vast tract of low green meadow-land. If we looked to the south, we might have seen the new buildings of Westminster Abbey, unless when the Danes had been on the warpath. If we looked to the eastward, we found that the Thames washed up close to our feet.

At this early period, and down to the reign of King Edward I., there were no houses in sight, except those which clustered about the Abbey, those which constituted the village of Charing, and in the far distance the grim walls, the red-tiled roofs, and the church towers of the City. London was more plainly visible than it is now, and on account of a curious bend in the course of the Thames, was nearly as visible from Westminster. By the thirteenth century a great change had come over all the district. The Thames was better confined within its proper limits; [Pg 7] some measure of embanking had been carried out, and a great many alterations in City life, in Church arrangements, and in the King’s policy have been detailed in the histories of London. We need not go far into them here. Before 1200, all the land between the Abbot and London belonged to him. By 1222 all was changed, or about to be changed, and the Abbot owned nothing except the advowson of the far-off St. Bride’s. St. Bride’s belongs to Westminster even now. The King laid claim to certain foreshores on the banks of the Thames. Undoubtedly, they belonged by an ancient grant to the Abbot, but we must take into consideration that what had been only occasionally dry land in the eleventh century was permanently dry in the thirteenth; and the King had conferred, and was conferring, too many benefits on the Abbot and his monks and their church to permit them to dispute his royal, if illegal, pleasure. The Bishop of Exeter formed a little estate of the Outer Temple. From his precincts westward the constant embanking, and especially the formation of the roadway of the Strand, left a wide strip now permanently dry. This strip the King erected into a manor, and bestowed upon his wife’s uncle, Count Peter. Peter became Count of Savoy in 1263, and the manor has ever since been called after him. The next of these reclamations was Whitehall. In the lawsuit already mentioned, a document was produced which threw great light on the early history of the district. It relates to the sale by Roger de Ware and Maud, his mother, to Hubert de Burgh, of their land here. Another document was a similar sale by Odo, the King’s goldsmith, of an adjoining plot, identified as stretching from the highway to the Thames.

Hubert’s choice of a residence was determined, no doubt, because it placed him within easy reach of the city on one side, and of the King’s palace on the other. He probably seldom used the road through the newly-constructed King Street, or the other road through the Strand—a road famous for ruts and mud. He went either to Westminster or to London by water, as did his great neighbours in the Savoy, and the bishops who had palaces outside the Bar of the Temple. We often wonder why our ancestors preferred these low-lying places for their houses. The answer is the difficulty they experienced in locomotion by land. [Pg 8] The “silent highway” of the Thames was such a convenience that all who could possibly afford it preferred to be within easy reach of water.

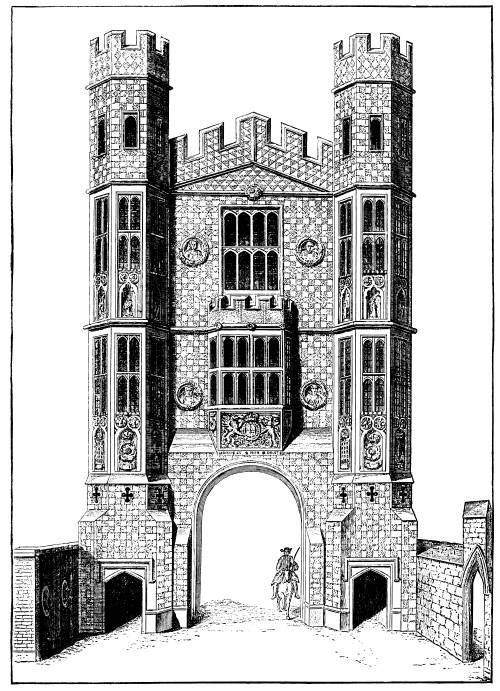

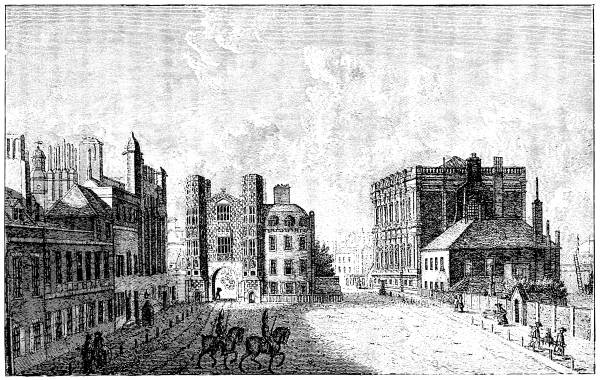

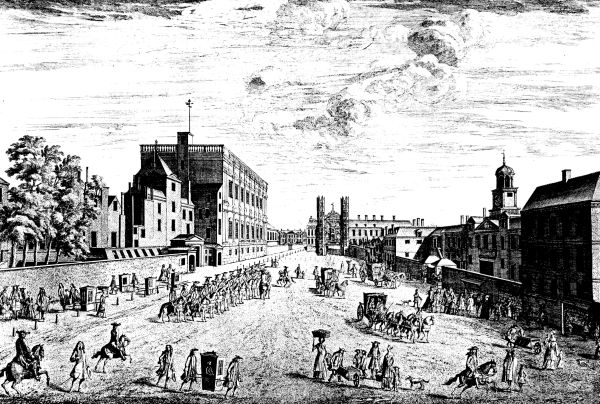

Hubert had no easy part to play. From 1227 he had to do daily battle with the young King, who already, though still a boy, showed signs of the combined obstinacy and incompetence which characterised him through life. Hubert saw the impolicy of yielding to the papal claims. He followed, as Bishop Stubbs remarks, in the footsteps of William Marshall, taking a middle path between the feudal designs of the great nobles and the despotic theories of the late King. In both these particulars he was in opposition to Henry, who was bound to the Pope by his education, and to the retrograde party by his personal prejudices. Hubert served the King too well to please the people, and spared the people too much to satisfy Henry. In 1232 he was dismissed, and his ungrateful master, not content with his dismissal, trumped up a series of charges against him, just as Henry’s descendant, Henry VIII., did with regard to Cardinal Wolsey. Hubert had been made Earl of Kent in 1227, and Constable of the Tower of London just before his disgrace—in fact, only a few days before—and during the same month was himself lodged in the Tower as a prisoner. Eventually his lands were restored, but he was not allowed to leave his castle at Devizes; he survived till 1243, when he died, as Matthew Paris relates, “full of days.” He had been five times married, and reckoned among his wives the widow of King John, and the sister of Alexander III., king of Scotland; but he left only two children, John, his son, and Margaret, his daughter. The subsequent history of the land now called Whitehall, so far as Hubert was interested in it, may be briefly detailed. Hubert had made a vow to go to the Holy Land and fight the infidel, being himself, as Roger of Wendover says, Miles strenuus; but not being able to fulfil his vow, he gave his land at Whitehall, which he describes as being in the parish of St. Margaret’s, into the hands of trustees to be sold in aid of an expedition to the Holy Land. The trustees promptly sold it to Walter Grey, archbishop of York, who annexed it to his See. Walter died in 1255, and was succeeded by Sewall Bovill, who had been Dean of York. Thirty archbishops in all held this house, beginning with Walter Grey [Pg 9] and ending with Thomas Wolsey. It is curious to remark that no trace now exists of their occasional residence. It was uniformly called York House, and we may be sure that Wolsey improved it, and built a hall and a chapel similar to those at Hampton Court. One or two old views show us stately and lofty buildings in the half-Gothic, half-Italian style, which is so familiar at Christ Church at Oxford, and at King’s College at Cambridge. A large hall was in King Street; that is, outside Holbein’s Gate. We see it beyond the gate in Silvestre’s view; and it stands up dark and heavy, with its strong buttresses on the left hand, in T. Sandby’s view. In the last century, when it had been part of the Treasury buildings for generations, it was newly fronted in stone, and the buttresses turned into pilasters. Since then it has been refronted twice—by Soane in 1824, and by Barry in 1846. Barry greatly increased the length. It would be interesting, but almost impossible, to ascertain if any of the masonry of Wolsey’s building still remains within the new walls.

This is, of course, a digression. No part of the Treasury is in Whitehall; but the reason for mentioning it is that its inclusion in the two engravings I have named shows us what, in all probability, Wolsey’s other buildings were like. Paul Hentzner, writing in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, says that they were “truly royal.” Very little building of any importance went on under Henry VIII. or his three immediate successors, so that Hentzner’s allusion must be to what Wolsey left. It is true, as we shall see, that Henry proposed to improve and extend it; but we may rest certain that he added nothing to its magnificence, if we except the gates; as the anonymous author of Dodsley remarks, he had a greater taste for pleasure than for elegance of building, and immediately on entering upon possession he ordered a tennis court, a cockpit, and a series of bowling-greens.

But we are going too fast. In the beginning of 1530 Cardinal Wolsey was still in possession, and there are various accounts of how he transferred the palace of his predecessors to the King. Henry was not very scrupulous in matters of this kind. He was much given to breaking the tenth commandment, and especially to coveting his neighbour’s house. He had already helped himself to Hampton Court, and a curious anecdote will be found in Thorne’s Environs. Lord Windsor was [Pg 10] much attached to his place at Stanwell, which had descended to him from a long line of ancestors. The house, no doubt, was in what agents nowadays call ornamental repair. He entertained the King royally, and Henry, with the kind of gratitude peculiar to him, promptly commanded him to hand it over. He gave in exchange the Manor of Bordesley and the Abbey, which Henry had taken from the monks. Windsor had just laid in a stock of provisions for his Christmas festivities, but he refused to remove them, saying that the King should not find it bare Stanwell when he came to take possession. The curious part of the story is that Henry does not seem ever to have visited it again, and we know that he soon afterwards leased it away. At the time of Wolsey’s fall, Henry had been for several years almost without a home in London; his apartments at Westminster were burnt in 1512, and after twenty years, in 1532, he bought the hospital of St. James’s-in-the-Fields. Between these dates he would have been without a London palace, except the Tower or Bridewell, but on the fall of Cardinal Wolsey certain illegal formalities were complied with, and Henry became possessed of Whitehall. The gates north and south of the royal precincts were needful on account of the old right of way between Charing—now become Charing Cross—and Westminster; and in 1535 Henry built the church of St. Martin, near to where the royal mews had been from time immemorial, with a view to prevent the constant passage of funerals from the northern to the southern part of St. Margaret’s.

In addition, Henry acquired all the land between Charing Cross and an outlying suburb of Westminster known as Little Cales, or Calais. More than this, he annexed all the green to the westward, which I have already mentioned. Abbot Islip had, in fact, nothing left of the great manor which after the Conquest had belonged to Westminster Abbey. The City of London had acquired the great ward of Farringdon Without. The lawyers had the Inner and Middle Temples. The King had inherited from the wife of John of Gaunt all the manor of the Savoy. And now Henry VIII. helped himself to the remainder. [Pg 11]

Banqueting Hall, Holbein’s Gate, and Treasury.

From the Engraving by J. Silvestre, 1640.

[Pg 12] It will be interesting to see the document by which the Abbot conveyed the inheritance of his house to the King. I am tempted to quote it nearly whole, but recommend the reader who is not interested in such things to skip on. No more quotations of the kind occur in this little book, but some readers may find the numerous landmarks enumerated worth making a note of, as most of them have long been obliterated:—

“To all Christ’s faithful people to whom this present writing indented shall come: John Aslyp, abbot of the monastery of St. Peter, Westminster, and the Prior and Convent of the same monastery, Greeting in the Lord everlasting: Know ye that we, the aforesaid Abbot, Prior, and Convent, with the unanimous assent, consent, and will of our whole Chapter, in our full Chapter assembled, have given, granted, and by this our present charter indented, confirmed to Sir Robert Norwich, Knight, our Lord the King’s Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Sir Richard Lyster, Knight, Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Sir William Pawlett, Knight, Thomas Audeley, serjeant-at-law of the Lord the King, and Baldwin Malet, solicitor of the Lord the King: a certain great messuage or tenement commonly called Pety Caley’s, and all messuages, houses, barns, stables, dove-houses, orchards, gardens, ponds, fisheries, waters, ditches, lands, meadows, and pastures, with all and singular their appurtenances in any manner belonging to the said great messuage or tenement called Pety Calais, or to the same messuage adjoining, or with the same messuage heretofore to farm, let, or occupied; situate, lying, and being within the said town of Westminster, in the county of Middlesex. And also all those messuages, cottages, tenements, and gardens situate, lying, and being on the east side of the street, commonly called the Kynge’s Strete, within the said town of Westminster, in the aforesaid county of Middlesex, extending from a certain alley or lane, there called Lamb Alley, otherwise called Lamb Lane, unto the bars situate in the aforesaid Kings Street, near the manor of the Lord the King there, called York Place. And also all other messuages, cottages, tenements, gardens, lands, and water, late in the tenure of John Henburye, situate, lying, and being on the said east side of the highway aforesaid, leading from a certain croft or piece of land commonly called Scotlande, to the Chapel of St. Mary de [Pg 13] Rouncedevall, near the cross called Charyng Crosse. And also all those messuages, cottages, tenements, gardens, lands, and wastes, lying and being on the west side of the aforesaid street, called the Kynges Strete, extending from a certain great messuage or brewhouse, commonly called the Axe, along the aforesaid west, side, unto and beyond the said cross called Charyng Crosse. And also all other lands, tenements, and wastes, lying on the south side of the highway leading from the aforesaid cross called Charyng Crosse, unto the hospital of St. James in the Field. And also all those other lands and meadows lying near and between lands lately belonging to the aforesaid hospital of St. James on the south side of the said hospital, and so from the aforesaid hospital on the south side of the highway extending towards the west unto the cross called Cycrosse, and turning from the same cross extending towards the south by the highway leading towards the town of Westminster, unto the stone bridge called Eybridge, and from thence along the aforesaid highway leading towards and to the aforesaid town of Westminster, unto the south side of the land there called Rosamundis, and so from thence along the aforesaid south part of the aforesaid land called Rosamundis, towards the east, directly unto the land, late parcel of the aforesaid great messuage or tenement called Pety Calais, and to the same great messuage or tenement belonging, containing in the whole by estimation, eighty acres of land more or less, and one close late in the tenure of John Pomfrett, now deceased, containing by estimation twenty-two acres of land, lying in the parish of St. Margaret’s, Westminster, in the aforesaid county of Middlesex, except always and so as the aforesaid Abbot, Prior, and Convent, our successors and assigns, wholly reserved as well as the aqueduct coming and running to our aforesaid monastery.” [Pg 14]

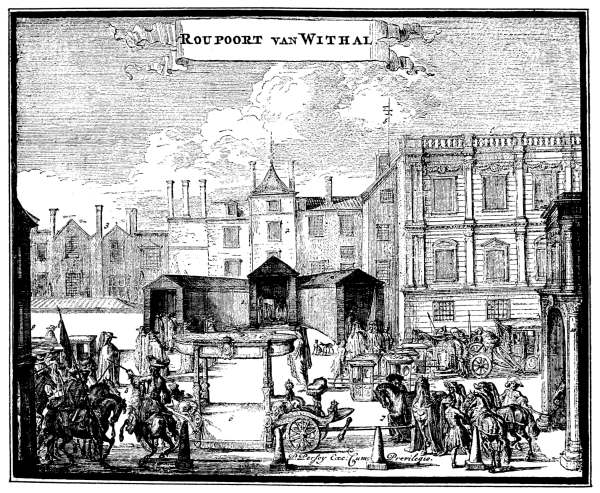

Holbein’s Gate.

From the Engraving by G. Vertue, 1725.

[Pg 15] Had Henry foreseen the course which his policy of confiscation would lead him into, he might have waited till 1539, when all the monastic estates became his. However, there is much to interest us is this strange document. We see that when Henry had annexed Whitehall to Westminster in such a way as to call the two by the same name—that is, “our palace of Westminster;” and when he had annexed the whole expanse of St. James’s Park, to both, and had made of St. James’s a kind of lodge to Whitehall—when from St. James’s he could look up the green hills towards Hyde Park, which he had also taken from the Abbot of Westminster, and beyond that again towards Hampstead Hill—the intervening country being all open and void—he took special leave from a subservient Parliament to make the whole into “an honour.” “Forasmuch as the King’s most royal Majesty is most desirous to have the games of hare, partridge, pheasant, and heron preserved in and about his honour at his palace of Westminster, for his own disport and pastime to St. Giles’s-in-the-Fields, to our Lady of the Oak, to Highgate; to Hornsey Park; to Hampstead Heath; and from thence to his said palace of Westminster, to be preserved and kept for his own disport, pleasure and recreation; his highness therefore straightly chargeth and commandeth all and singular his subjects, of what estate, degree or condition soever they be, that they, nor any of them, do presume or attempt to hunt, or to hawk, or in any means to take, or kill, any of the said games, within the precincts aforesaid, as they tender his favour and will eschew the imprisonment of their bodies, and further punishment, at his Majesties will and pleasure.”

Henry spent considerable sums of money in making an orchard, probably where the so-called Whitehall Gardens are now. Two thousand five hundred loads of stone were used in this work and in enclosing St. James’s Park. But the only additions to Wolsey’s building seem to have been a long gallery which ran northward towards Charing Cross; there was also a passage, but of what kind we do not know, “through a certain ground named Scotland.”

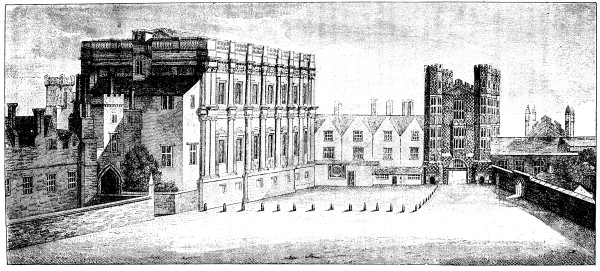

There are numerous engravings extant of the northern gateway. It was in the most florid taste of the day. Perhaps we can best realise its appearance by a visit to Hampton Court. The great gate there is made of ornamental brickwork and decorated with terra-cotta statues or busts. Thomas Sandby’s drawing shows the view from King Street very well. On our left are the buildings of the Treasury. To the right beyond the gate is the Banqueting House. Apparently when this view was taken the gate had become wholly detached from what remained of the palace after the fire of 1697. Wilkinson’s view (I. 143), from a drawing by Hollar, taken in the early part of the reign of Charles I., shows a line of [Pg 16] four gables connecting the gate and the Banqueting House, and we know that a gallery or passage led from the park, through the first floor of the gate to the palace. By this circuitous route it was that Charles reached the place of his death. In Hollar’s view the arch of the gate contains a flat ceiling and a window, which greatly spoils its appearance. At the park end of the passage there was a staircase. Adjoining this end of the passage, and very near where Downing Street stands now, was a tilt-yard, and close to it a small barrack for the Foot Guards. Beyond it, further to the north, was the yard of the Horse Guards, very much as it is still. Behind the spot where James I. built the Banqueting House, to the eastward, was the court, a very irregular space, divided by a passage passing over an archway. This passage led to the great hall and the chapel, which last was close to the river’s bank. The King’s lodgings also looked on the Thames, but between them and the chapel there was a labyrinth of small chambers and sets of chambers. To the westward of these small and inconvenient apartments, some of which were appropriated for the Queen and her maids of honour, was the great Stone Gallery, which looked on the garden and the bowling green. How far these arrangements were due to Cardinal Wolsey and how far to Henry VIII. we cannot say. Undoubtedly, the whole palace was most inconvenient, even at that day, when men’s ideas of comfort were so different from ours. There was not, if we except the so-called Great Hall, a very small building compared with that of Hampton Court, a single large or handsome chamber in the whole place. Room was, however, found for a library, and Paul Hentzner mentions it with praise. In it he saw a book in French written by the Princess, afterwards Queen, Elizabeth, with her own hand, and inscribed to her father: Elizabeth sa très humble fille rend salut et obédience. “All these books,” continues Hentzner, “are bound in velvet of different colours, though chiefly red, with clasps of gold and silver; some have pearls and precious stones set in their bindings.” There are probably a few representatives of this library among the books which belonged to Henry VIII., and have his name or arms, in the British Museum. Hentzner also notices the furniture of inlaid woods, some stained glass representing the Passion, and a gallery of portraits and other pictures. He visited Whitehall in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, when the place must have been very much as it was left by Henry VIII. He mentions, among other things, the Queen’s bed, “ingeniously composed of woods of different colours, with quilts of silk, velvet, gold, silver, and embroidery.” Among the portraits is one, the description of which puzzles me: “A picture of King Edward VI., representing at first sight something quite deformed, till by looking through a small hole in the cover, which is put over it, you see it in its true proportions.” Can this have been a device of the same sort as the distorted skull in Holbein’s picture of “The Ambassadors” in the National Gallery? [Pg 17]

Whitehall, from King Street.

From a Drawing by T. Sandby, R.A.

Engraved by R. Godfrey, 1775.

[Pg 18] Henry VIII. continued to date documents of all kinds at “Westminster,” meaning Whitehall. It is possible that St. James’s was similarly included in Westminster. In or about 1537 the King’s house there was greatly improved and beautified, it is said by Cromwell, in anticipation of Henry’s marriage with Anne of Cleves. The initials “H. A.” on some of the fireplaces and ceilings were probably put up in allusion to the same marriage, and have nothing to do with Anne Boleyn. It was intended that Henry and Anne (of Cleves) should pass their honeymoon at this remote corner of the park as it was then, there being no buildings whatever visible from the gate. The result we all know; and Henry, long before the honeymoon had waned, was back at “Westminster.” Events travelled rapidly in those days. Anne Boleyn was beheaded in May, 1536. In the same month Henry was married to Jane Seymour. She died in October, 1537. In January, 1539, Henry married Anne of Cleves, and divorced her in July. In April following Cromwell became Earl of Essex, and was beheaded in July of the same year. No doubt Whitehall was the principal scene of the long tragedy indicated by this dry list of dates. At “Westminster” Henry conferred a peerage on Cromwell’s son, Gregory; and there, too, he issued letters of naturalisation to the Lady Anne of Cleves, and gave her several manors. One more tragedy and we have done with Henry VIII. On a day unknown, in January, 1547, the King lay dying at Whitehall. So weak had he become that he was obliged to leave it to others to execute his cruel and relentless orders. He died at Whitehall on the 28th, the last act of his life having been to send the poet Surrey to the scaffold, and to prepare a similar fate for Surrey’s father, the Duke of Norfolk. The Duke being a peer, the process for obtaining an act of attainder was slower. A commission had been issued by the tyrant to Wriothesley, St. John, Russell, and Hertford to give the King’s consent to the Bill. But death stepped in and the Duke’s life was saved. [Pg 19]

Whitehall.

From an Engraving after a Drawing by Hollar

in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge.

[Pg 20] Sandford gives a very circumstantial account of the funeral ceremonies at the burial of Henry VIII. It is chiefly interesting because he names several apartments of Whitehall Palace. At first the body lay in the King’s private chamber, and there received some embalming treatment, and was wrapped in lead. The chapel, the cloister, the hall, and the King’s chamber were all hung with black. On the 2nd of February the coffin was taken into the chapel. We read of cloth of gold and a pall of tissue. The altar was covered with velvet, adorned with scutcheons of the Royal arms. Twelve lords, mourners, sat or knelt within the rail. Watchers likewise took turns of duty, and, as the people passed by, a herald cried to them, saying, “You shall of your charity pray for the soul of the most famous prince, King Henry VIII., our late most gracious king and master.” The body was not to lie in the sumptuous but despoiled chapel Henry had raised for his father and mother. On the 14th of February the wax effigy was ready, and a procession, which Sandford says was four miles long, started for Windsor. Henry had desired to be buried beside Jane Seymour. Syon was reached the first night, and the journey was ended at one o’clock the next day.

There is nothing to connect Edward VI. with Whitehall during his short reign. But Mary, his successor, was constantly there. She is said to have preferred St. James’s, and the first separate mention we have of it in a State paper is in December, 1556. She died there in November, 1558.

Elizabeth made much use of Whitehall, but her buildings and improvements at Windsor must have proved a powerful attraction. She went about a good deal, and her State papers are signed in a great variety of places. She left no mark on Whitehall, although, at the very [Pg 21] end of her reign, instead of Henry the Eighth’s “palace of Westminster,” we have “Whitehall,” pure and simple, one or twice. We have seen how York Place became the Palace of Westminster. How it again changed its name, and became Whitehall, we do not know. The change seems to have been made by Elizabeth shortly before her death, and the name may have already been in popular use. After her death, at Richmond, in March, 1603, her body lay in state at Whitehall, and was buried in the Chapel of Henry VII.

With the Stuarts we have a new epoch in the history of Whitehall.

Accession of the Stuarts—Wallingford House—Henry, Prince of Wales—Masks at Court—Inigo Jones—The Banqueting House—The Great Design of 1619.

The accession of the Stuarts marks a new epoch in the history of Whitehall. In spite of edicts against building, Charing Cross had become a populous place, and one of James’s first acts had been to build new stabling and a barn in the Mews on the site now occupied by Trafalgar Square. North-east of Whitehall, the Strand had become a continuous street, which ended with what we remember as Northumberland House, then called Northampton House, and subsequently Suffolk House. South of the palace, King Street had also been completed, and in a house there Edmund Spenser, the poet, died “for lake of bread,” as Ben Jonson reports. He “refused 20 pieces sent to him by my lord of Essex, and said he was sorrie he had no time to spend them.” East of King Street, where now we see Mr. Norman Shaw’s fine police office and Richmond Terrace, were green fields and gardens sloping to the Thames. The curious old Gothic gate made an entrance to King Street, and stood just at right angles to where we see the chief entrance to the Foreign and India Offices. The Palace garden, with its sun-dial lawn, was separated from the King Street slopes by the Bowling Green, where is now the house of the Duke of Buccleuch. On the other side of the roadway of Whitehall, beyond, that is to the northward of, the Tilt Yard and Horse Guards, Sir William Knollys, who was Treasurer of the Household to Queen Elizabeth, built himself a house to be near the Court. James I. made him a peer, as Lord Knollys, in 1603. In 1616 he became Viscount Wallingford, and his house long bore this name. Ten [Pg 23] years later he was advanced to the earldom of Banbury, and died in 1632. There were complications as to his marriage, in 1606, with Lady Elizabeth Howard, and his titles have been claimed unsuccessfully, at intervals ever since, by his reputed descendants. We shall have more to say about Wallingford House presently.

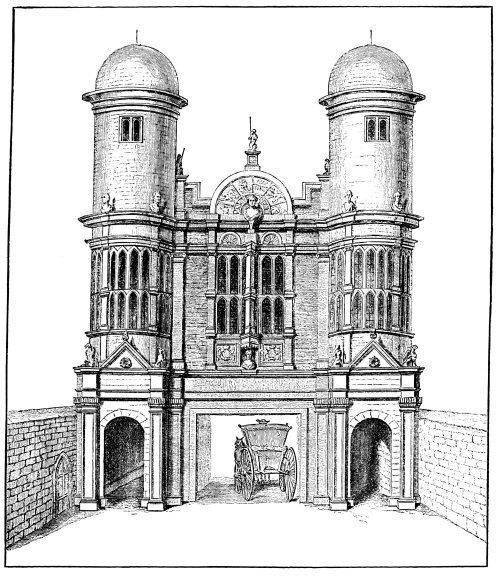

The King Street Gate.

From the Engraving by G. Vertue, 1725.

[Pg 24] The new King must have looked on Whitehall as but a poor lodging. The Queen had Somerset House, between the Strand and the Thames, for her separate residence, and the Prince of Wales had St. James’s. To be more accurate, we may quote Mr. Sheppard to the effect that, though St. James’s was granted to Prince Henry the year after the King’s accession, he did not go into residence there for six years. Two years later he died. It is worth while to go into these things, because, among the four hundred persons and personages who composed the Prince’s train, was a “surveyor,” or, as we should say, an architect, named Inigo Jones, reputed to be a great traveller, but more in vogue at Court as a “devyser of maskes.” He had three shillings a day for his pay, and the Prince gave him as much as thirty pounds on one occasion (which, as Cunningham, his biographer, remarks, was equal to one hundred and twenty pounds of our money), and sixteen pounds on another. When the Prince died, Jones, who had a promise of the Royal Surveyorship at the next vacancy, went to Italy, no doubt to study, having probably saved something during his two years at St. James’s.

There are many notices of masks performed before the King’s Majesty at Whitehall in the early years of the new dynasty. These plays took place in the Hall, which, as we have seen, was near the Chapel in the eastern part of the palace. It must have been small and inconvenient for such purposes, but Inigo, who on many occasions is mentioned as having looked after the arrangements, was fertile in resource, and made the most of the space at his disposal. He was destined to furnish the palace with an adequate hall, which is now the sole relic of the old royal residence existing. It is quite worth while to quote (from Cunningham) Jones’s account of one of these plays. It was written by Chapman, and was acted by the gentlemen of the Middle Temple and Lincoln’s Inn at the time of the marriage of the Princess Elizabeth with the Palsgrave, afterwards King of Bohemia. First, a procession started from the Rolls House in Chancery Lane, and rode on horseback along the Strand, past Charing Cross, to the Tilt-Yard at Whitehall, where they made one turn before the King, and then dismounted. The performance took place in the Hall. It is described as having for [Pg 25] scenery an artificial rock, nearly as high as the roof. The rock was honeycombed with caves, and there were two winding stairs. The rock turned a golden colour, and “was run quite through with veins of gold.” On one side was a silver edifice labelled in Latin, “The Temple of Honour” (Honoris Fanum). There were various allusive devices, and after Plutus, the God of Riches, had made a speech, the rock split in pieces with a great crack, and Capriccio stepped out to make his speech while the broken rock vanished. Next appeared a cloud. Then a gold mine, in which the twelve masquers were triumphantly seated. Over the gold mine was an evening sky, and the red sun was seen to set. There were white cliffs in the background, and from them rose a bank of clouds, which hid everything. The mask cost Lincoln’s Inn alone more than a thousand pounds. Of course, scenery of the kind described must have been extremely costly, the designer having neither the appliances nor the skilled workmen who carry out such marvellous scenic effects in our modern theatres.

One more example of Inigo’s powers as a “devyser” may be quoted from Cunningham. In 1611, in January, the Prince, then nearly at the end of his short life, presented a mask at Court, that is, at Whitehall. It was written by Ben Jonson, and called “Oberon, the Fairy Prince.” It cost 289l. 8s. 5d. for mercery, 298l. 15s. 6d. for silk, and 143l. 13s. 6d. for tailor’s work; in all, the Prince had to pay 1092l. 6s. 10d. The interest of these details lies in the fact that it was by making stage scenery that Inigo Jones was taught how to extract the greatest amount of effect from the smallest amount of material or means. It let him into the secret of proportion, and the marvellous amount of influence proportion alone, without ornament or expense, can be brought to exercise. Other men at that time also understood stage scenery, but stage scenery was to them nothing more. The information so gained fell on fertile soil in the mind of Inigo, and brought forth eventually those splendid architectural designs for which he can never be too much praised.

Inigo Jones carried the information and experience thus obtained with him on this his second visit to Italy. He enquired why such a building had such an effect. He made careful measurements, and compared and [Pg 26] combined the figures so arrived at until he wrung the secret of the old Roman builder from the ruins. Cunningham dwells at some length on this subject. There can be no doubt that, like Wren’s, the genius of Jones consisted mainly in his extraordinary power of taking pains. Where one man was content to observe the completeness and harmony of some palace or church, Jones must find out to what cause that harmony was due. Thus he went about making measurements. For instance, he always carried a copy of the great work of Andrea Palladio with him wherever he went. On the fly-leaves he constantly wrote such notes as this:—“The length of the great courte at Windsour is 350ᶠᵒ, the breadth is 260; this I measured by paces the 5 of December, 1690. The great court at Theobalds is 159ᶠᵒ, the second court is 110ᶠᵒ square, the thirde courte is 88ᶠᵒ—the 20 of June, 1621.” The book is now at Worcester College, Oxford. One of his notes is very curious as showing his subtle analysis of proportion. He had a great admiration for the Temple of Jupiter at Rome, and set seriously to work to find out the reason for its satisfactory effect. In the result he came to the conclusion that its design was based on a series of circles, and that its proportions were fixed by dividing the largest diameter into six parts, and then recombining them. In June, 1639, he noted of this temple that it had just been destroyed by the Pope’s permission for the sake of the marble built into the walls. The Bishops of London have here ancient precedent for their treatment of Wren’s City churches, and what Inigo would have thought of some recent doings may be gathered from the next two notes:—“This was the noblest thing which was in Rome in my time. So as all the good of the ancients will be ruined ere long.”

On the 1st of October, 1615, he was put in possession of the office of Surveyor to the King, which had been promised him before he left England. His predecessor, Simon Basil, had died in that year, and we cannot doubt that he immediately commenced the series of designs by which it was intended to transform the shabby rabbit-warren, that, as we have seen, the so-called Palace of Whitehall had become. Otherwise, it is impossible to believe that when, in 1619, the old hall of which I have so often spoken, was destroyed by fire, he was ready within six [Pg 27] months to begin the building of the Banqueting House. We must remember that this house, which is so familiar to all Londoners, was part of a design intended to cover a space of 1152 feet by 874. It was expected to rival the great palaces of the continental kings. The Vatican may be said to have been completed in 1588, and the smaller palace of the Lateran in 1586. At that time the largest of these palaces was the Escurial in Spain, which had been completed late in the previous century. The front is more than 680 feet in length. Versailles had not been begun, and neither had the largest of all, the palace of Mafra, on the west coast of Portugal, not far from Lisbon.

Mafra is 760 feet in width, east and west. It forms at the present day a conspicuous, but not beautiful, object from the deck of the passing steamer, but is seldom visited, as it has nothing except its vast size to recommend it. But the palace of Whitehall was designed by Inigo Jones to be both larger than any other, and also so beautiful that even the little fragment with which we are familiar has challenged the admiration of every one who has any architectural taste for more than two hundred and fifty years.

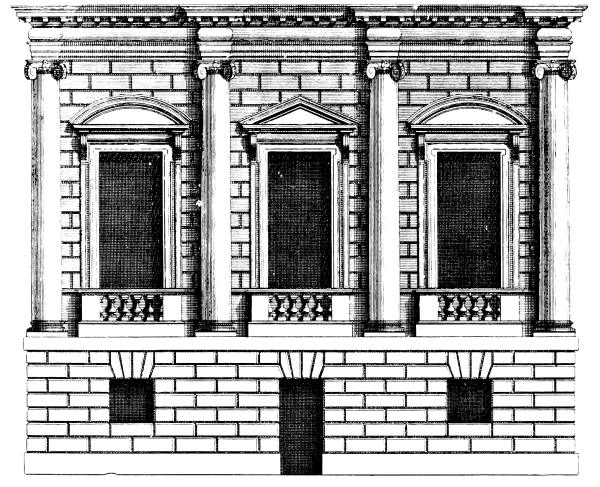

Detail of Banqueting House.

From Kent’s “Inigo Jones.”

When the fire in Whitehall Palace took place, it did not require that the King should summon Jones to repair the damage. Any work of that kind was part of his daily round: but two interesting points should be mentioned here. Inigo made no attempt to restore the burnt building, nor did he undertake, as a modern architect would have done, to make a new hall, and persuade his employers that it was exactly as Cardinal Wolsey had left it. On the contrary, he offered the King plans of which the Banqueting House was but a small part. Evidently he had carefully examined the site, and found that there was ample room for a building on the greatest possible scale. The palace as it then was, reached from the very bank of the Thames to the roadway of Whitehall; and, on the western side, looking into the park, there was a kind of village of buildings attached to the palace more or less slightly. The whole space available was about 4000 feet from north to south, and 1300 from east to west. On the side of the park the space was practically inexhaustible; the King could take as much as he pleased in that direction. We shall give some description of the whole design presently. [Pg 28] Jones within six months was ready to begin upon his new Banqueting House, and on the 1st of June, 1619, the first stone was laid, the architect having submitted a model to the King. The building was finished at the end of March, 1622, the expenditure having been 14,940l. 4s. 1d. It is remarkable that the account was not finally settled until long after the death of King James, namely, in 1633. It may be well here to give the technical account of the new building, probably written by Jones himself. It was described as 110 feet in length, and 55 in width within. The wall of the foundation is 14 feet in thickness. The first storey to the height of 16 feet was of Oxfordshire stone, rusticated on the outside and bricked on the inside. The Banqueting Hall was 55 feet in height to the roof, the walls being 5 feet thick, made of Northamptonshire stone, with two [Pg 29] orders of columns and pilasters, the lower Ionic and the higher Composite, with their architrave, frieze, cornice, and other ornaments of the kind; also rails and “balustres” round about the top of the building, all of Portland stone, with fourteen windows on each side; one great window at the upper end, and five doors of stone with frontispieces and cartouches; the inside brought up with brick, finished over with two orders of columns and pilasters, part of stone and part of brick, with their architectural frieze and cornice, with a gallery upon the two sides, and the lower end borne upon great cartouches of timber carved, with rails and “balustres” of timber, and the floor laid with spruce deals; a strong timber roof covered with lead, and under it a ceiling divided into a fret made of great cornices enriched with carving; with painting, glazing, &c. The master-mason was the famous Nicholas Stone, who sculptured the water-gate at the foot of [Pg 30] Buckingham Street, and to whom Cunningham attributes the monument of Sir Francis Vere in Westminster Abbey. If the beautiful wreaths and the capitals of the pilasters are still as he left them, they show exactly that kind of reticence which is one of the most charming characteristics of really high art. Inigo was too good an architect to leave anything like this to a workman in whom he could not thoroughly confide, but it is evident that what Gibbons did for Wren, Stone did for Jones.

Detail of Banqueting House.

From Kent’s “Inigo Jones.”

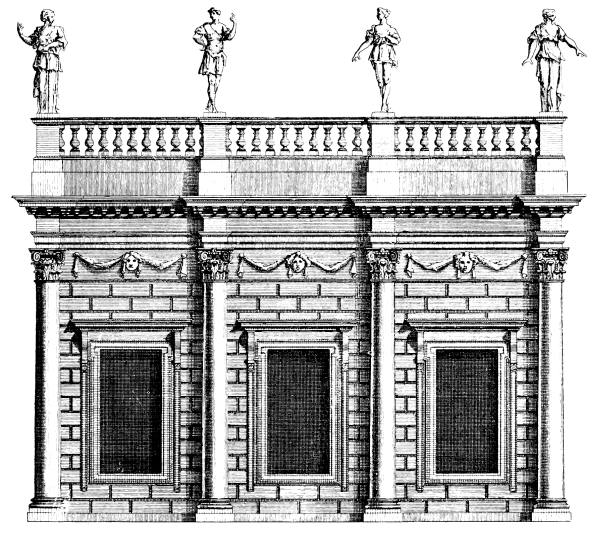

It will have been perceived that the proportions of the interior were those which all but the modern anomalous architects have found to be the best. The room is formed of a double cube, the height being equal to the width, and the length double the height. A gallery was supported on engaged columns of the Ionic order. An upper order was of Corinthian pilasters. The roof was flat and divided into nine compartments, with very handsome mouldings between. The central compartment was oval, and contained Rubens’s principal picture of the “Apotheosis of James I.” This beautiful chamber was never designed for a chapel. We shall have occasion to describe further on what Jones designed for that purpose. It is reported that Rubens was assisted in these pictures by Jordaens. He received three thousand pounds for them, and they have been cleaned and restored several times at considerable expense. The figures are colossal, the children being more than nine feet high. The Banqueting House, though never consecrated, was made a Royal Chapel in 1724. Two years ago it was handed over to the United Service Institution, who have added to the south side a building which, in my opinion, forms a serious eyesore. It is curious that with all the wealth of design left by Inigo Jones, and ready to the hands of the Institution, they could not find something better than that by which they have disfigured every view of the Banqueting House. A great French architect named Azout, who visited England about 1685, is said to have declared that this “was the most finished of the modern buildings on this side the Alps.” To a sincere lover of beauty in architecture, this opinion will commend itself. It is sometimes said that the famous cartoons of Raphael were brought to England as designs for the tapestry for the Banqueting House. [Pg 31] After the death of King Charles, they were sold, and were purchased by the Spanish Ambassador, Alonso de Cardanas. This is likely enough, as also that he sent them into Spain. Some hangings, said to be the same, but of this there could be no proof, were brought to London and exhibited at the Egyptian Hall, in Piccadilly, in 1825. They represented passages in the Acts of the Apostles. What became of them we do not know. I have only seen them mentioned in Tymms’s account of Whitehall in the second volume of Britton’s Edifices.

Section of the Banqueting House.

From Kent’s “Inigo Jones.”

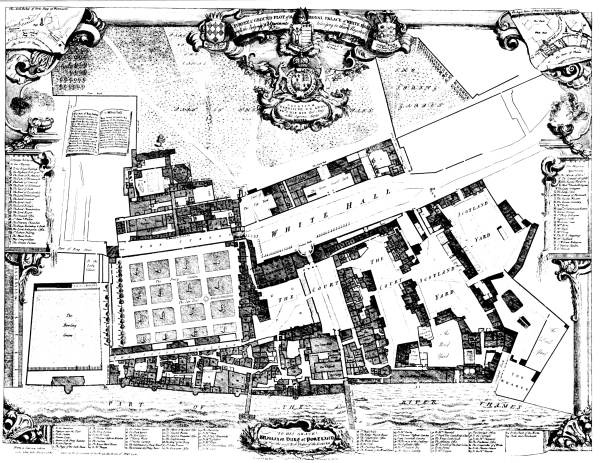

[Pg 32] A curious question arises, which is not very easily answered: Where would this building have stood in the complete palace? The visitor entering the great court would have found three other buildings resembling this one. Two were to be at the northern end on either side, and two more at the southern end. Connecting them were two buildings of much greater beauty and of large size, the whole court being no less than 378 feet wide and 728 feet long. If, as Fergusson and others have asserted, the Banqueting House was at the north-eastern corner, it would be on the visitor’s left, while a chapel would have been on his right. At the centre of the façade on the right was the entrance to the royal apartments, which were thus arranged to be on the western side and to look out on the park, to the south of the Treasury. On the opposite side of the great court access was to be obtained to a noble hall, suitable for state occasions, and, in fact, the buildings on this side, which were to look on the river, were of a public character as distinguished from the private apartments of the King and the royal family. If, as seems probable, the Banqueting House stood at the north-east corner, and if we look at the plan of Whitehall which George Vertue engraved for the Society of Antiquaries, we find that Inigo’s building is nearly in the middle of the palace. If we measure 728 feet to the southward, it takes us all that distance towards Westminster, and overwhelms in building-stone the whole of the Privy Garden and part of the Bowling Green. All the great ranges of buildings to the northward—the kitchen court, the wood-yard, the small beer-buttery, and the two Scotland Yards—would have had to go. We can but conjecture that Inigo wished to have a grand open space before his Charing Cross façade—what the French call a “place d’armes.” On the Westminster side there could not have been much space beyond the Bowling Green. The park, of course, was open, and so was the river. Much thought accordingly was spent on these fronts, and perhaps that to the Thames shows Jones at his very best. No description can do it any kind of justice; but it may be worth while to mention the principal points. The centre was of three storeys, the lowest with rusticated pilasters. The next storey has features common to much of the design, but two flanking buildings only two storeys high are marked by a studied plainness, flat pilasters being between the windows. At either end of the front we find three-storey pavilions—we can hardly call them towers. They, like the centre, have engaged columns standing well out. The most beautiful thing on this front is a projecting portico in the centre, three arches wide and one deep. This beautiful balcony—the most elegant little bit in the whole design—is of the Corinthian order, two storeys high, the lower rusticated, and on a balustrade above are the statues with which Inigo always liked to relieve his sky-line.

Apotheosis of James I.

Plan of Whitehall.

Engraved by G. Vertue,

from a Survey made in 1680.

[Pg 34] The Westminster side had an archway “for the street of Whitehall” and the right of way. It is open through the ground storey and an entresol, and is flanked by two massive towers of four storeys, crowned by small cupolas.

The Charing Cross front being to the north was kept studiously plain. It was not until our own day that an architect put lavish decorations on that side of a building. Wren knew as well as Jones that mass, not ornament, is appropriate to this aspect, and we used to be able to admire his taste in the north transept of Westminster Abbey, now altered. The delicate proportions, the fine central archway, and the arcade at the western end of the façade, make up a very pleasing composition, and, viewed across a wide parade-ground, would have produced a marvellously picturesque effect.

On the King’s side—that is, to the westward of the street—was to be a circular court, which most architectural critics have highly praised. It has always been known as the Persian Court. Caryatides, we may remark, are female figures, Persians male. It consisted of a kind of circular corridor, two storeys high. Kent gives several views with sections of this Persian Court. Instead of pillars or pilasters were Caryatides in the upper range, and Persians in the lower. Those in the lower range had Tuscan capitals above their heads; those in the upper had Composite or Corinthian capitals. Here Inigo departed from his usual rule, and covered the wall with the most elaborate ornament. The court looks very well in Müller’s bird’s-eye view, but not so well in Kent’s elevations and sections. The plan shows that the circular corridor would have formed a most convenient passage connecting the King’s and Queen’s private apartments with those of their attendants. Two wide square courts were to north and south. [Pg 35]

First Design by Inigo Jones for the Rebuilding of Whitehall

. Waterside Front. From Müller.

[Pg 36] The other wing, so called, of the palace had also three courts, the interior architecture of which we may judge of by looking at the back, or east, side of the Banqueting House, which was built to form part of the north-eastern court on one side, and to look on the street of Whitehall on the other. The Chapel was to have corresponded in the north-western corner. Jones left elaborate plans for this building, and a section in Kent is one of the most beautiful things in a beautiful book. It was a double cube, of course, but the roof was vaulted, or, at least, coved. Elaborate symbolical carving and angelic figures are on the wall. The chapel has a narrow gallery above, and the order, which is Ionic, fluted, below, is Corinthian above. Wide-arched openings are in the view in Kent, but he does not show us what the other, or chancel, end was to be like. It may be worth noting that, like Wren, Jones was very free in his use of the orders, and it is not always possible in the prints to distinguish Corinthian from Composite; but, of course, where the lower storey was Ionic, the upper would not be Composite.

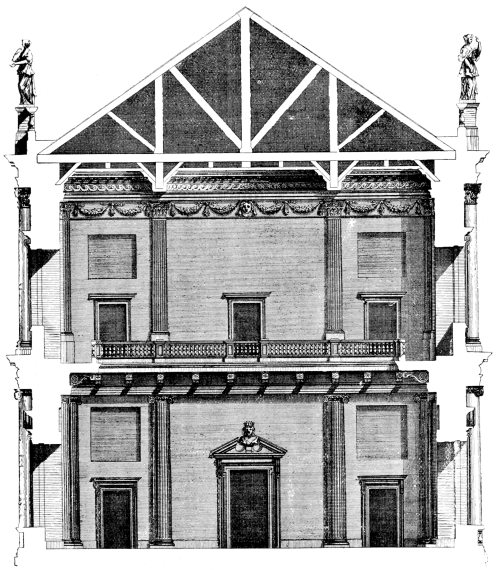

As to the merits of this design for a palace, critics have been very well agreed—except, unfortunately, during the madness of the supposed Gothic revival. Had Barry been desired to use, or adapt, Jones’s design, or part of it, for the new Houses of Parliament, what a noble river-front we might have had! But it is useless to pursue such thoughts. The opportunity was lost, and, for certainly the past thirty years, there have been very few people in England who were really able to judge of the Houses of Parliament apart from their ornamentation. Inigo Jones’s design would have been the better of any ornament that could have been bestowed on it, but ornament was not necessary. Marble columns and gilt capitals would have looked well, but plain stone would have been enough. [Pg 37]

First Design by Inigo Jones for the Rebuilding of Whitehall.

Bird’s-eye View. From Müller.

Fergusson well remarks that the greatest error in Jones’s design for Whitehall was the vastness of its scale. It was as far beyond the means as beyond the wants of James I. It is not, he continues, in a long passage from which I only take a few sentences, so much in dimensions as in beauty of design that this proposal surpassed other European palaces. Externally, it would have surpassed the Louvre, Versailles, or any other building of the kind, “by the happy manner in which the angles are accentuated, by the boldness of the centre masses in each façade, and by the play of light and shade, and the variety of sky-line, which is obtained without ever interfering with the simplicity of the design or the harmony of the whole.”

[Pg 38] Sir William Chambers, the last of the Inigo Jones and Wren succession, speaks especially of the circular court described above. There are few nobler thoughts, he observes, in the remains of antiquity. The effect of the building, properly carried out, would have been surprising and great in the highest degree. The diameter of the court was to be 210 feet, the ground floor being an open arcade or cloister.

Jones wholly misapprehended the depth of the King’s purse when he made a design of so costly a character. Otherwise, we must conclude that he made these beautiful drawings for his own pleasure—a kind of vision which he knew could never be realised. That this is not a correct statement of the case seems to be proved by what followed. Let us take the Banqueting House as a unit. It cost, roughly speaking, 20,000l., of which sum 15,000l. was for the mere building. Three similar buildings in the same court would have cost at least 60,000l., the chapel more than the rest. This foots up at once to 80,000l. The Persian Court could not have cost less than 50,000l. Add to this the two magnificent halls, and we have 80,000l. more. Yet we have only accounted for two of the seven courts, and have said nothing of the four fronts. We feel tempted to think that Inigo, like the person mentioned by Tennyson, built his soul “a lordly pleasure-house, wherein at ease for aye to dwell,” and that he neither intended nor expected that King James should carry it out. That this is not the case we can judge by the design he made for Charles I. in 1639. It was to be of only half the dimensions, and was to be studiously plain. Whereas the Banqueting House was one of the plainest and least costly features of the 1619 design, it would appear in the new view as one of the most elaborately ornamented. But he [Pg 39] misjudged the purse of the son, as he had misjudged that of the father. Not a stone was ever laid, and when, a few years later, the war broke out, it was hopeless to think that Charles, though sorely in need of a commodious and really royal residence, could ever build, even after the new and modified design presented to him by his Surveyor. [Pg 40]

Part of the First Design by Inigo Jones

for the Rebuilding of Whitehall, 1619.

From Kent’s “Inigo Jones.”

Part of the Second Design by Inigo Jones

for the Rebuilding of Whitehall, 1639.

From Campbell’s “Vitruvius Britannicus.”

[Pg 42] The chief points of this design may be briefly indicated here, as the next chapter will be filled with matters of a very different character. The western front was to be towards the street of Whitehall; that is to say, the palace was to be less than half the size of that designed for James I. No archways were needed across the road. In the middle of this façade was a fine arch, opening between the Banqueting House toward the north and the Chapel, the corresponding building toward the south. The wall between was very simple, only containing three rows of square-headed windows. What would have been a beautiful and picturesque [Pg 43] feature were the domed towers which formed the ends of the front, each containing a triple Venetian window. The side to the river was to have a kind of arcade or cloister; but the Persians and the Caryatides have disappeared, with most of the reception-rooms and public halls. This design was brought forward again after the fire in 1698; but William III. was too busy with the Continental war, and probably also too poor to do anything. It is worth more than a passing glance, and includes some of Jones’s most matured work. Campbell obtained it in 1717 from an “ingenious gentleman,” probably an architect, and possibly the architect whom William proposed to employ in rebuilding the palace. It will be found in the second volume of the Vitruvius Britannicus.

Accession of Charles I.—Unfavourable Omens—“The White King”—Henrietta Maria—Her French Followers—The Royal Pictures—Their Partial Sale—The King and Queen at Dinner—Death of Strafford and Laud—Charles at Westminster—Place of the Scaffold—Last Scene.

James I. died in 1625, at Theobalds, having removed thither from Whitehall shortly before. His son Charles I. succeeded him, and for the first years of his reign lived in the old royal apartments on the Thames’ bank. The omens observed at the time were all against the new King. Had his reign been prosperous we should have heard nothing about them. First of all, it was remarked that the breath was hardly out of King James’s body when the Knight Marshal, in proclaiming his successor at the gate of Theobalds, made a bad blunder. He said Charles was the late King’s rightful and dubitable heir. He meant to have said “indubitable.” When the news came to Whitehall, Bishop Laud was in the middle of his sermon, for it was a Sunday, and broke off in order to let Charles be proclaimed, nor did he afterwards conclude, so that the new King and the congregation went away without a blessing. At the coronation, in February, 1626, it was similarly noticed that no procession through the City from the Tower to Westminster could take place, because the plague was raging. Several still more ominous accidents marked the day. The wing broke off the golden dove which formed part of the regalia. The Bishop of Carlisle, Richard Senhouse, by an inexcusable blunder, took for the text of his coronation sermon, “Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life,” from the Revelation. This was much remarked upon then and afterwards, and it is very possible that Charles alluded to the sermon in the last words he ever uttered. But another circumstance was most remarked upon that dark February day in the gloom of the old Abbey. For some unexplained reason, Charles was dressed, not in purple, like the kings before him, but in white satin. Later on this gained for Charles the name of “The White King,” and at his burial, in February, 1649, at Windsor, in a snow-storm, as the flakes fell upon the coffin, there were some present who remembered the omen of twenty-three years before. Finally, as if to crown all, that day was marked in the memories of many by a shock of earthquake.

[Pg 45] There is little at first to connect Charles with Whitehall, but towards the end of the coronation year a curious scene took place there. The King, weary of the young Bishop and his twenty-nine priests who had come over with Henrietta Maria, decreed that they must return home. This they were very unwilling to do. With them were also to go an immense crew of attendants, whose vagaries disturbed both Whitehall and St. James’s. They exceeded in numbers even the four hundred who had formed the household of Henry, prince of Wales. Contemporary letters are full of their arrogance and greed. With the French priests came a crowd of English Jesuits and the like, whose position, as the law stood then, was wholly illegal. The story that Henrietta Maria had to do penance at the instance of her French confessor, by going barefoot to Tyburn to glorify the memory of the Gunpowder Conspirators, rests on very slight evidence. One thing is certain: if she went, it was at the instance of one of the English priests. Even at the present day few Frenchmen know anything of English history thirty years old. It was, however, one thing to resolve, another actually to get rid of these intruders. At first the King wrote to Buckingham, who was then at Paris, to try to persuade the queen-mother of the necessity of the step he contemplated, and, moreover, to ask her to “find a means to make themselves suitors to be gone.” Whether she complied or not, the [Pg 46] Queen’s servants were far too well off to think of moving. Marshal Bassompierre came over in order to arrange matters, but without avail. His report of a stormy interview with Charles is a mass of bombast. The King, coming to Whitehall, and entering the Queen’s apartments to [Pg 47] inform her that he must be obeyed—that he had put the matter into the hands of that stern soldier, Lord Conway, who had arranged everything—found “a number of her domestics irreverently dancing and curvetting in her presence.” He took her by the hand, led her into an adjoining chamber, and locked himself in with her.

The Guardroom, Scotland Yard.

From an Etching by J. T. Smith, 1805.

Meanwhile, Conway took the French Bishop and his priests into St. James’s Park, and informed them briefly of the King’s unquestionable causes of complaint, and of the arrangements made for their immediate departure. The Bishop refused to move, saying he regarded himself as an ambassador. Conway replied that he might regard himself as he pleased, but that if he did not depart peacefully he would be turned out by force. [Pg 48]

Next, Lord Conway entered Whitehall, where he firmly but politely informed the French servants of the Queen of his errand. They were to go first to Somerset House in the Strand, where he proposed to make separate arrangements for each of them. The women screamed and stormed, and after Conway had given them reasonable time, he summoned the yeomen of the guard, who thrust them out forcibly and locked the doors after them. They went to Somerset House, where Charles himself visited them the same afternoon.

More than a month later they were still at Somerset House, when Lord Conway was again called in; but, what with the obstinacy of the Bishop, and the clamour of the women, it took four days and forty carriages to transport them to Dover. The whole story is in Ellis’s Letters, and in D’Israeli’s Curiosities of Literature, and is well summarised by Jesse in his Court of England under the Stuarts, to which I may refer a reader interested in the subject; my own concern having, of course, been only with that part which related to Whitehall.

That Charles should have been forced into war, and, above all, a civil war, was a great misfortune to the progress of civilisation, as shown in the arts and sciences. Painting, music, architecture flourished at his Court, together with poetry and science. He probably brought more fine pictures into England than all the kings put together since his time. Walpole says, “As there was no art which Charles did not countenance, the chasers and embossers of plate were among the number of the protected at Court.” Casting in bronze was a favourite art, and Fanelli, who made the statues of Charles and his Queen at St. John’s College, Oxford, should be named, as well as Le Sœur, who made the King’s equestrian statue which is now at Charing Cross, but which was originally made for Lord Portland and set up at Roehampton. The King’s cabinet pictures were lodged at Whitehall in a chamber expressly built for them by Inigo Jones. Undoubtedly the pictures were, of all his works of art, those which Charles chiefly loved. He contrived to acquire a magnificent collection, and it is evident from one or two entries that Jones had a general commission not to let anything slip [Pg 49] which would prove a desirable addition to the royal gallery. Although his taste lay chiefly in ancient pictures, Charles largely patronised Van Dyck, and Van Dyck’s principal pupils and contemporaries, such as Janssen, Walker, and Dobson. Moreover, he bought on occasion lavishly. The collection of the Duke of Mantua came into the market, and was bought whole by the agents of King Charles. He hung it on the walls of the Banqueting House, but intended to have embellished that building with paintings by Van Dyck, representing ceremonials of the Order of the Garter. These would naturally have comprised portraits of most of the great men of the day. There was also a scheme on foot for establishing a school of art somewhat on the lines of our Royal Academy, but more distinctly intended for teaching. This, of course, fell through, like all other schemes of the kind, during the civil war. Before his death the leaders of the Commonwealth endeavoured to sell off or otherwise make away with the treasures of art which Charles had gathered. Their animosity against pictures containing representations of the second person of the Holy Trinity or of the Virgin Mary induced them to order their destruction. That very few of these orders were carried out is plain from the list preserved by Walpole. We are anticipating the order of events if we pause here to describe the gradual dispersal of the great royal collection. The sale went on at intervals from 1648 to 1653, but many pieces remained in England. Some did not even leave Whitehall, and there are now many in the National Gallery which once belonged to the unfortunate Charles.

The best account of the sale is that written by Horace Walpole, who used for his purpose the notes of George Vertue, the engraver. The prices were fixed, but the highest bidder, if more was offered, was adjudged the buyer. We cannot do better than take some items from Walpole’s list. The cartoons of Raphael were bought in by Cromwell for the insignificant sum of 300l. The other cartoons, those representing the triumphs of Cæsar, by Andrea Mantegna, went for 1000l., and were also reserved for Cromwell. They had formed part of the Mantua Gallery already referred to. Apparently they had been removed from Whitehall to Hampton Court, where they have ever [Pg 50] since remained. We read of many Madonnas; one, said to be by Raphael, fetching 800l.; but another Raphael, afterwards estimated much more highly, was the celebrated “St. George and the Dragon,” sometimes called “St. Michael,” now in the Louvre. A Venus, called “Del Pardo,” by Titian, sold for 600l. The “Mercury teaching Cupid, with Venus standing by,” painted by Correggio, which is now in the National Gallery, went for 800l. This had also formed an item in the great Mantua Collection. The picture had many adventures. The Duke of Alva took it to Spain and subsequently it became the property of the famous Prince of the Peace, in whose collection it remained until 1808, when it fell into the hands of Murat. It thus found its way back into Italy. Lord Castlereagh bought it and the “Ecce Homo,” which hangs near it, from the ex-Queen of Naples at Vienna, and in 1834 it was purchased from Lord Londonderry for the National Gallery. Rubens’ “Peace and War” was presented to Charles by the painter in 1630. It now only fetched 100l., and went to the Doria Gallery at Genoa, whence it was sold, brought back to England, and presented to the National Gallery in 1828 by the first Duke of Sutherland. After the Restoration, strong efforts were made to gather the dispersed pictures again. The States of Holland bought the whole collection of Gerard Reyntz and presented them to Charles II. on his restoration. The Government went to law with Van Leemput, who had bought a great portrait of King Charles I., by Van Dyck, for 150l. There were various negotiations, in which Van Leemput was offered a fair compensation. As he refused, the law was put in force, and Van Leemput got nothing. This must not be confused with the Marlborough Van Dyck which is now in the National Gallery. It is plain, remarks Walpole, from a catalogue made for James II., that a large number of pictures remained at Whitehall unsold, and it is very possible that Oliver Cromwell intervened, when he had the power, to prevent their sale. We must always thank his taste for having rescued the two great sets of Mantegna’s and Raphael’s cartoons. It will be observed that though the store was by no means exhausted, the sales ceased in 1653, the year of his inauguration as Protector. In 1660 Cromwell’s widow tried in vain to retain possession of some pictures and other treasures. [Pg 51]

Before we go on to speak of the great tragedy which gave Whitehall a world-wide celebrity, we may make a note from a passage quoted by Mr. Law in his catalogue of the pictures at Hampton Court. One of these pictures represents Charles I. and his Queen dining in public. The picture is by Van Bassen, who also painted the King and Queen of Bohemia similarly employed. Mr. Law’s account of the first-named picture is very interesting, and relates mainly to life at Whitehall. The King and Queen are being “served by gentlemen-in-waiting with dishes, more of which are being brought in from the door opposite them by attendants. In the right corner is a sideboard, and wine cooling in brass bowls on the floor. Several dogs are running about. At the end of the hall is a raised and recessed daïs, where spectators are looking on through some columns. The decoration of the hall is in the classic taste, and is very fine and elaborate. On the walls hang several pictures.” Though this doubtless belonged to Charles I., it is not found catalogued among his pictures; but in the catalogue of James II. we find No. 937: “A large piece, where King Charles the First and Queen, and the Prince are at dinner.” It is dated over the door, on the right, 1637. It is engraved in Jesse’s Memoirs of the Stuarts, and is chiefly valuable for the architecture and decoration, and as exhibiting the manners of the time, and the prevalent custom in that age of royalty dining in public. “There were daily at Charles I.’s Court, 86 tables, well furnished each meal; whereof the King’s table had 28 dishes; the Queen’s, 24; 4 other tables, 16 dishes each, and so on. In all about 500 dishes each meal, with bread, beer, wine and all things necessary. There was spent yearly in the King’s house, of gross meat, 1500 oxen; 7000 sheep, 1200 calves; 300 porkers, 400 young beefs, 6800 lambs, 300 flitches of bacon; and 26 boars. Also 140 dozen geese, 250 dozen of capons, 470 dozen of hens, 750 dozen of pullets, 1470 dozen of chickens; for bread, 364,000 bushels of wheat; and for drink, 600 tuns of wine and 1700 tuns of beer; together with fish and fowl, fruit and spice, proportionately.” (Present State of London, 1681.)

As to Henrietta Maria at dinner, an anecdote is reported by Jesse: “Notwithstanding her conciliating manners on her first arrival in [Pg 52] England, it soon became evident that the spirit of Henry IV. was not entirely dormant in the bosom of his daughter. A singular scene, which took place at Court, shortly after her marriage, is thus described by an eye-witness. ‘The Queen, howsoever very little of stature, is yet of a pleasing countenance, if she be pleased, but full of spirit and vigour, and seems of a more than ordinary resolution. With one frown, diverse of us being at Whitehall to see her, being at dinner, and the room somewhat over-heated with the fire and company, she drove us all out of the chamber. I suppose none but a Queen could have cast such a scowl.’” (See Jesse’s Court of England under the Stuarts, ii. 16.)

The whole sad history of the Great Rebellion has been told at full length in divers places, and only incidentally concerns us here. We see that Charles was shifty and wanting in straightforwardness. None of his political opponents could trust even his promises. No one could deny him both courage and coolness in the hour of danger. We might dwell on what might have happened if he had saved Strafford; but the bold policy in which that would have landed him—the policy Strafford himself described as “thorough”—though it might have rid him of his enemies, would have cost a tremendous price to the nation. When Charles promised Strafford to save his life, he had scarcely power to make his promise true. He gained nothing by Strafford’s death, and only lost one of the two or three really able advisers he had. It is not possible to believe that he thought the savage fanatics who clamoured for the great minister’s blood would pause and ask no more. “Moderation” was a word that did not exist in their vocabulary, and it is rather melancholy to see John Milton made the mouthpiece of a series of foul scandals on a King whose private life seems to have been absolutely pure, as Milton must have known. But politics were up to boiling point in those days. It was not enough to defeat an opponent in the House or at the poll; he must be put to death. So far the traditions of the Tudor times survived. Having stimulated their appetite by the death of Strafford, under legal forms and with the unwilling consent of the King, they proceeded to murder, by the travesty of a judicial process, the highest [Pg 53] they could find in the country. Archbishop Laud was brought to trial, or rather to condemnation, in March, 1644, and in January, 1645, he was beheaded. There was only left to quench their thirst for the best blood in the land a few nobles—the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and others; but there was one victim, the highest of all, and they had no notion of sparing him, though, by compassing his death, they ruined their own cause.

Lambeth and Whitehall.

From the Engraving by W. Hollar.

We can easily see that a Prime Minister like Strafford had done many things to make himself hated. We can see that Laud was also hated, mainly for being an archbishop. Another minister or another archbishop would be appointed in course of time, and both would be hated, and that, too, by a great many people who were, on the whole, loyal to the Crown, if not to the person of Charles. The death of Charles at Whitehall changed the feelings of this whole class. They may have groaned, as we hear they did. Some groaned because their King was killed, even though they may have thought he deserved his fate; but the great majority saw that all the good the popular party might have carried out for the people was annihilated at that one blow. Murderers are seldom moderate and beneficent reformers, though Agathocles did [Pg 54] contrive to succeed in both these rôles in Sicily. But that was a long time ago and a long way off, and few of the truer patriots of 1649 looked at these violent proceedings without both apprehension and horror—apprehension lest a murder of such huge dimensions should only mean anarchy in the Government and oppression of the people—as, in effect, it did—and horror at the perpetration of such an irrevocable crime without any reference to the people, either at the hustings or by a direct vote. But it appeared as if the Parliament, though, with the help of the army, it could kill the King, could not dissolve itself. The soldiers, however, without the Parliament, could, and did, force a dissolution, and in our next chapter we shall see the chief leader of the rebels residing in the old palace of Whitehall as a sovereign prince.

The greatest of all these changes was simply this. If we allow, as many of the so-called Puritans did, that the King had strictly forfeited his life, imprisonment, like that inflicted on Henry VI. for many years, or exile, like that which James II. afterwards underwent, would have been a sufficient penalty. France would not have gone to war to reinstate a Protestant dynasty, as it did not half a century later go to war to reinstate a Romanist, and the longer Charles I. lived the more improbable the return of his son became. But that scaffold at Whitehall altered the state of affairs. Instead of a King who certainly had not deserved well of his people, it gave them a young and, so far as they knew, an innocent and blameless King, whose coming they were forced, by the violence of the dominant faction, to hope for as for the salvation of their country.