TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

In the plain text version text in italics is enclosed by underscores (_italics_), small caps are represented in upper case as in SMALL CAPS and words in bold are represented as in =bold=.

A number of words in this book have both hyphenated and non-hyphenated variants. For the words with both variants present the one more used has been kept.

Obvious punctuation and other printing errors have been corrected.

The book cover was modified by the Transcriber and has been added to the public domain.

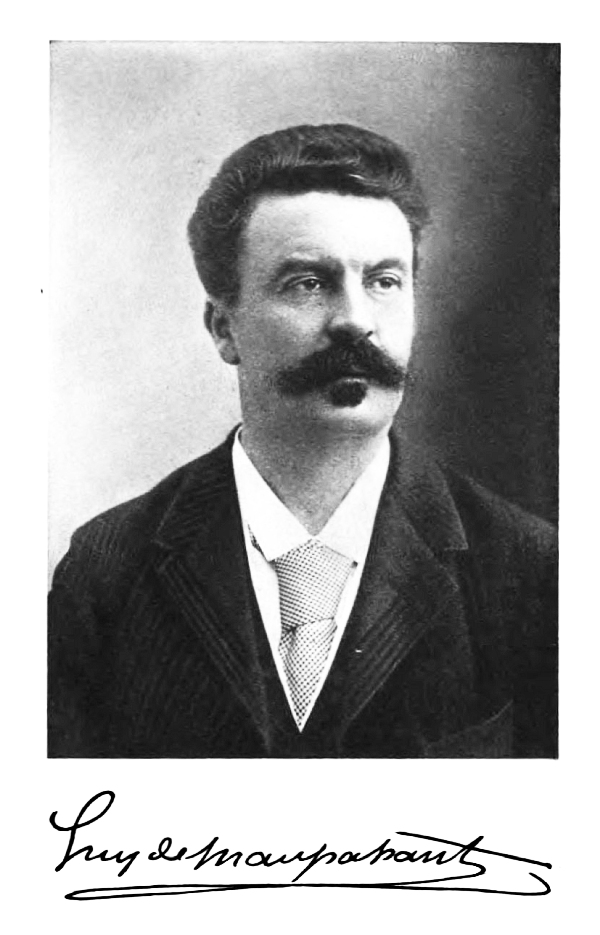

Guy de Maupassant

VOLUME I—FRENCH

DONE INTO ENGLISH AND WITH INTRODUCTIONS BY

J. BERG ESENWEIN

EDITOR OF LIPPINCOTT’S MAGAZINE

The Home Correspondence School

Springfield, Massachusetts

1912

Copyright 1911 and 1912—J. B. Lippincott Company

Copyright 1912—The Home Correspondence School

All Rights Reserved

CONTENTS

VOLUME I

| Page | |

| General Introduction: The French Short-Story | 3 |

| François Coppée and His Work | 21 |

| Story: The Substitute | 33 |

| Guy de Maupassant, Realist | 53 |

| Story: Moonlight | 61 |

| Alphonse Daudet, Man and Artist | 71 |

| Story: The Pope’s Mule | 85 |

| Prosper Mérimée, Impersonal Analyst | 101 |

| Story: The Taking of the Redoubt | 113 |

| Pierre Loti, Colorist | 123 |

| Story: The Marriage to the Sea | 137 |

[Pg 3]

In zest, movement, and airy charm, in glittering style, precise characterization, and compressed vividness, the French short-story is unsurpassed. German writers have excelled in the fantastic and legendary tale; Russians, in both mysticism and in unrestrained naturalism; British, in those subtle moral distinctions which reveal character under crucial stress; Americans, more or less in all these phases; but no nation has ever developed a school of story-tellers who say so much in so few words, and, withal, say it so artistically and pungently as do the French.

There is a real distinction between a short-story in French and a French short-story. The latter implies a national genre, and indeed this implication is sustained by an examination of French shorter fiction.

We are justified in asserting the existence of a national type of short-story in France, or in any other land, when its special literary product reflects in theme the typical spirit of the nation, when its attitude toward life is characteristic, when its literary style is decidedly marked by national idioms, and when local color—by which I mean an individual flavor of characters and[Pg 4] locality—is marked enough to be recognized as a literary trait. Tested by each of these four standards—which I have ventured to set up rather arbitrarily—the short-story in France is the French short-story.

A single example may serve to illustrate the application of these tests. Here, let us imagine, are two short-stories written in French and by Frenchmen. The one deals with a baseball game, played in Hawaii. Its argot is that of the “diamond,” and its attitude is that of the frenzied “fan.” The tone and the Hawaiian background will furnish local-color enough. The second story has for its theme a tragic family schism caused by the struggle over clericalism in France. The attitude of the characters is typical of the contesting parties, the language is richly idiomatic, and the local-color convincing. Of course it would require no wisdom to determine which was the French short-story and which merely the short-story in French.

Now, when the great mass of short-stories written in France meet two or more of these tests, we have a national type of short-story, and I believe that the ten stories grouped in these two little books sufficiently illustrate the French national spirit to warrant our accepting them as types.

[Pg 5]

At first thought it might appear that the same might be asserted of any nation where short-stories are produced—Italy, for example. But the facts would not bear out any such statement. True, some Italian writers are sufficiently imbued with their language and nationality, and yet sufficiently modern, to produce little fictions which are typically Italian and typically short-stories, but they are too few to constitute a school. The novel, poetry and the drama have thus far claimed the best efforts of Italian literary folk.

In these pages the word short-story is used somewhat broadly, yet with an eye to the technical distinctions between it and similar forms of short narrative.

Since the earliest story-writing of which we have record in the tales of the Egyptian papyri (4000 B. C.?), there have been short fictional narratives in many lands, some of which meet almost every requirement of the short-story form as we now know it. But that every such approach to the short-story was sporadic rather than from intention to conform to a recognized standard is certain because in each case there was shown no progress toward a repetition of the form, but, instead, a reversion to the types common to all short fiction—the straightforward, unplotted[Pg 6] chain of incidents which we call the tale; the light delineation of some mood, character, or fixed situation, likewise without real plot, which we name the sketch; the condensed outline of what might well be expanded into a long story, which we term the scenario; and the brief recital of some incident with a point, known as the anecdote.

With occasional accidental exceptions, as just noted, all the Egyptian tales, Greek and Roman stories, sacred narratives, mediæval tales, legends, and wonder-stories, and modern short fictions down to the first quarter of the nineteenth century, were of these four types.

The short-story as a conscious genre was developed in America and in France about the same time, with the weight of opinion favoring Poe as its “inventor.”

In 1830 Balzac began a brilliant series of novelettes, almost short-stories, which lack only compression and unity of impression to stamp him and not Poe as the first consistent and conscious producer of the new form. As it is, these remarkable stories are so near to technical perfection (as short-stories, for there can be little adverse criticism upon them as fiction), that he must share with two Americans the distinction of producing little stories which must have helped Poe materially to see the new form in clear constructive[Pg 7] vision—I mean Irving and Hawthorne. Prior to 1835—the date of “Berenice,” Poe’s first technically perfect short-story—both Irving and Hawthorne had produced short fictions incomparably in advance of any consistently frequent short narrative work theretofore. Irving’s style was kin to Addison’s essay-stories in the Spectator, and even in those altogether admirable tale-short-stories, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” the influence of the essay form is quite evident. Hawthorne’s stories were chiefly symbolical tales, up to 1835,[1] or expanded anecdotes done to create a single effect upon the mind. In this they rival the singularly potent unity of Poe’s best work. But shortly Hawthorne turned more and more aside from the short-story to the long symbolical romance, in which he stands without a peer in any land.

Then arose in France—for other countries require no further comment here—a series of notable story-writers, of supreme distinction in all that goes to make the short-story the most popular literary type: compressed delineation [Pg 8]of a single crucial situation, highly centralized leading character, swift characterization, deft handling of crisis, climax, and dénouement, and, throughout, masterful work in local color.

The short-story nomenclature among the French is not clearly translatable, for three reasons—we have no precise English equivalents, critics do not entirely agree upon what equivalents are nearest to the French terms, and, best reason of all, the French short-stories have this in common with all others: their forms often overlap, and so bear marks of touching more than one type. And when I have said this I have said nothing to their discredit; only the Procrustean purist first builds a bed and then stretches or cuts every story-guest to fit! I cannot say this in voice loud enough: to set up a standard of what is a true short-story is no more to decry those short fictive narratives which do not meet the form than it would be to brand the lyric as imperfect because it does not fulfill the requirements of the epic.

But, to be specific, the three terms which we constantly meet in French fiction are roman, nouvelle, and conte. The roman may be dismissed as a general term standing largely for what we in English variously denominate the (long) romance, the novel, and the (long) tale. The nouvelle most[Pg 9] nearly approaches our English short-story, but it also stands for the novelette, or very short novel, or even the expanded short-story. The conte is really a generic word for a short fictional narrative or any story that is short, like the tale, the anecdote, and the fictional sketch, without meaning specifically the short-story to whose characteristics of compression, unity of impression, and crisis, climax and dénouement of plot, I have just referred.

So I repeat: in these studies the term short-story must be given some latitude of interpretation.

The French short-story of the last eighty years is not only typically Gallic but characteristic of the period. Just as there are four tests of nationality in fiction so there are four forces which contribute to its periodicity: The influence of the soil, the heritage of the preceding period, the special characteristics of the period itself, and the influence of surrounding nations. All these result in what may be called the Spirit of the Period, concerning which a word must be said presently.

The primacy of the French as conteurs is doubtless due quite as much to the rich and colorful provincial life which surrounds the capital as to their priority as tellers of short tales. It has been[Pg 10] said that Paris is France. Nothing could be less true. Here is a nation which presents the unique paradox of being at once and supremely homogeneous and heterogeneous. The life of each province is part of its soil, colored by the soil—or by the ever-present sea. Yet France has a spirit of nationality equalled by no other nation. While what is now the German Empire was still an unrelated number of minor peoples or an integral part of some vaster state, France was a unified or at least a closely federated kingdom. While Britain was changing under its successive tides of invasion, what was essentially France was sending out its national culture world-wide—it over-climbed the Pyrenees, it spread into the Low Countries, in the west it conquered the Swiss tongue, it permeated the Rhenish provinces, it implanted Norman life in Britain. Thus grew the French national spirit.

Yet the provinces held tenaciously to their own picturesque types, spoke their more than a hundred patois, wore their folk costumes, sang their native songs, danced their own dances—unchanging through the centuries. And nowhere more than in the French short-story may we see depicted the peculiar French provincial traits. The folk of Champagne and Picardy are shrewd, subtle, ardent, and born conteurs—witness the[Pg 11] stories of Juliette Lamber. Those of Berry are stolid and solid, as pictured by Madame Nahant. The Gascons are vivacious, daring, and cunning, as set forth by Emil Pouvillon. The people of Languedoc are simple, strong and violent, as described by Georges Baume. The happy, excitable sun-children of Provence, reveling among their olive groves and vineyards, have been portrayed by Alphonse Daudet; the picturesque Provençal sailors and fisherfolk live again in the stories of Auguste Marin; while Paul Arène has done loving service not only for Provence but for Maine as well. Maupassant has given us notable portraits of the Norman—bold, tricky, ambitious, economical, and of superb physique as befits the sons of sturdy men-at-arms. Loti’s stories are redolent of the salty spume of rough, melancholy, religious Brittany. And so, in the same recognition of rich material, Theuriet paints Lorraine, Erckmann and Chatrian the Rhine province of Alsace, Fabre the Cévennes, Anatole le Braz the Breton coast, Mérimée Corsica, Maupassant Auverne, and Balzac Touraine. What a wonderful color box has the French story-painter always open to his brush! Truly the soil and the sea have marked this period of the short-story as well as the novel.

The inheritance of the preceding period—that[Pg 12] of the Revolution, the First Empire, and the First Restoration—was rich in war pictures, dramatic episodes of intrigue, and a never-so-remarkable display of contrasts in human passion and changing conditions. The French short-story is therefore full of these national conditions.

The period itself, 1830-1912, witnessed kaleidoscopic social and governmental changes—the Second Restoration, the Bourgeois Monarchy, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, the Franco-Prussian War, the Commune, and the Third Republic, to say nothing of numberless minor attempts at change. All these filled the story-teller’s pack with rich national materials. Especially are the problems of socialism, militarism and clericalism in evidence.

Finally, the influence of surrounding peoples has been felt not only in the content but in the form of the French short-story.

All these forces, and others less ponderable, have fused into what I may term the nineteenth century French spirit, as illustrated and measurably interpreted by the French short-story.

Three sub-tones of this French symphony, to use a trope, are emotional nature, passion for military glory, and religious sentiment. Emotional endowment the French, in common with other Latin races, possess—a fact which calls for[Pg 13] no comment. The military spirit, chastened by the experiences of the Franco-Prussian War, has been decreasingly in evidence during the last four decades, yet indications are not wanting that the fire burns none the less vitally because smothered by practicalities. The war-theme constantly recurs in the short-story, and “glory” is still dear to every Frenchman. As for the third element, religion, the evidence is more contradictory. France has always felt a deep undercurrent of religious feeling. Her public worship has perpetuated this ideal in churches many and noble, as well as in a pomp of ceremonial peculiarly suited to an artistic Latin people. But I should seek for the surest proof of the religious spirit not so much in these signs as in the life of the provinces, the influence of the church there, and their constant manifestations of religious faith. The clerical crisis was not confined to the great cities, so that the last twenty years has shown marked changes in public sentiment, but there are potent signs of a reaction toward free religious life, for France will be church-loving. The typical abbé lives in her fiction as beautifully as does the soldier.

And so I have ventured to name emotion, war, and religion as three significant sub-tones of French life. But there are five other phases of the[Pg 14] French spirit which show out in the short-story, though they do not seem to me so fundamental. Of these now a few words.

We find, first, volatile sentiment, as shown in quick changes of attitude, sudden concentrations, extremes of gayety and depression, lively speech, and a general habit of regarding a tempest in a teapot as a serious crisis, with now and then a surprising way of smiling away a real tragedy. There is much of the child-nature here, and therefore the loving, the lovable, and the sweet.

Love of hearth is another French characteristic, the mistresses and assignations, true and fictive, to the contrary notwithstanding. The typical homes of any nation are found less in its cities than in its smaller centers; and so it is in France, for the bulk of high-grade fiction is pretty certain to be a safe index of public feeling.

A third characteristic is the unique attitude of the French toward womanhood. The mother, in France, is honored above belief; the wife somewhat less so; the young girl knows nothing, and is therefore merely amusing; the woman of easy morals occupies a large place because she must be reckoned with as a recognized factor. The whole attitude of France toward its womanhood is compounded of sentiment, lightness, and cynicism. Less independent than the American[Pg 15] woman, less free than the English, less domestic than the German, the French woman is more a being to charm man than a companion for him. And so runs the current of the short-story, side by side with the sweep of life.

A fourth trait in the French short-story is a minute, detached observation, tinged with cynicism—the inevitable result of realism. It is for this reason that so many French short-stories seem unsympathetic. Scientific observation—really, a German trait—is likely to be cold when applied to tumults of the soul! And the writer who as a moral vivisectionist relentlessly applies the scalpel runs the risk of becoming blasé, not to say cruel. He is more concerned with the truth of facts than with extracting the truth from facts.

A final characteristic is artistry. To do a short-story with fineness, deftness, perfection of detail, and beauty of finish; to cut an intaglio, so to say, to paint a miniature, to inlay a jewel—that is the Frenchman’s conception of the artistic in brief fiction, and in that he is unsurpassed.

Here, then, are some qualities of the French spirit as evidenced in the short-story of the period—qualities fundamental and in the phase, but patent, as it seems to me, in a large proportion of the entire short-story product.

[Pg 16]

Viewing the subject generally, as one must in attempting a survey of so varied a field as the last eighty years in French fiction, there are several periods fairly well-defined in the movement of the short-story. As a differentiated type the short-story appeared at a time when classical ideals of form had broken down and moral ideals also had quite fallen. For three decades, precise, logical prose had been as cheerfully scouted as were old-fashioned swaddling-clothes of personal virtue. For a period equally long, “Freedom” had been the sweet word every one uttered with unction. Rousseau had laid his blade to the root of the existing order; Chateaubriand had broken loose from the fetters of old literary forms; Madame de Staël had coined the word “romanticism” with a new image and a superscription enchanting to the mind agitated by the sudden opening of the unknown; the success of French arms abroad had let in a flood of new ideas—the reign of romance was undisputed. Color, movement, dreams, enthusiasm—all these prose began to borrow from poetry. Charles Emmaniel Nodier—a classicist in form, but a romanticist in spirit—began his florid tales, while Théophile Gautier and Alfred de Musset applied their poetic skill to the telling of prose stories.

But the romantic movement began to wane in[Pg 17] the early forties, not, however, before reaching a brilliant high-tide in the work of the elder Dumas. Even Gautier would sometimes scoff in his supremely clever style at the extravagances of the period. But the chief force in this breakdown of the romantic school was Honoré de Balzac, whose brilliant short-story work, chiefly done from 1830 to 1832, laid the foundations of a new school of shorter fiction in France, as the de Goncourts and Stendhal had already done for longer fiction—for Balzac was less an originator than a developer of the psychological novel. However, in fiction long and short, his moderate realism stands to-day as the most important example of his school. Prosper Mérimée became a realist only after having begun as a romanticist; Alphonse Daudet never fully came under the sway of realistic principles; and Ludovic Halévy generally chose a romantic theme even when treating it realistically, so that we must turn to Balzac as the representative of his class.

In Gustave Flaubert, a stylist of the most finished order, but latterly a severe classicist, we find an example of the slight classical reaction which followed the reign of realism. A similar romantic reaction is seen in the short tales of the collaborators, Émile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrain, as well as of François Coppée. Here[Pg 18] the joint influence of the German Hoffmann and the American Poe is plainly evident.

But these reactionary movements were neither powerful nor for long. The disillusionment and cynicism of French life was bound to find expression in its fiction, and the more sincere and fearless the writer the more direct would be his methods. Naturalism became the final expression of realism, for naturalism is realism plus pessimism. Naturalism proposes not only to see things as they are and report things as they are seen, but it is a pessimist who sees and reports. Result—gloom, mire, and jagged stories, unkissed by a single star of hope! Émile Zola is the chief-priest, and Eugene Sue the industrious acolyte at the altar of this despairing cult.

No people, however, could long enjoy an orgy of depression, and signs of moderation soon appeared. Guy de Maupassant, with all his abnormality, and Paul Bourget with all his pessimism, now and then touched the joyous side, and by and by a braver, more wholesome tone sounded in the French short-story—a tone of eclecticism, both of method and of philosophy. Surrounded by a social order emancipated from many past ills and having the promise of greater equity, quieted by the more or less permanent settlement of at least two of its most vexed questions,[Pg 19] the France of to-day is encouraging a group of brilliant writers—Pierre Loti, Anatole France, Gustave Droz, Jules Lemaître, Jules Claretie, Renè Bazin, Jean Richepin, Marcel Prévost, and Paul Margueritte—who, though mostly no longer young, represent a youthful France in that they are emancipated from school and type and write as the story makes its call to their own natures. Sometimes one method, sometimes another, rises to dominance, but the choice of the most available is after all the current practice.

Of the future no man may tell, but backed by the rich traditions of literary France, the air of artistry all about, the growth of a more unselfish socialized life, and the promise of stable national conditions, we may well look for the most satisfying results in the French short-story of tomorrow.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] An inquiry into the development of the short-story in Russia at about this period has been reserved for the third volume of the series, which is devoted to short fiction of that land.

[Pg 20]

SHORT-STORY MASTERPIECES

[Pg 21]

There never has been a satisfactory definition of poetry, though all ambitious literary appraisers, from Aristotle down to Bernard Shaw, have essayed the task. But if to be able to institute apt and beautiful comparisons; to phrase in musical language thoughts of power, beauty, and feeling; to discern the ideal clothed in the real; to interpret the inner meanings of life—if this ability marks the poetic gift, then François Edouard Joachim Coppée was a poet—a poet in prose as well as in verse.

Very early in life the young Parisian—he was born in Paris, January 12, 1842—began to write verses which showed marks of distinction, and he was only twenty-four when Le Reliquaire, his first poetic volume, appeared. Two years later, Poèmes Modernes and La Grève des Forgerons were issued, establishing his place among modern poets of his land. And when, in 1869, at the age of twenty-seven, he produced Le Passant, a group of exquisite comedies in verse, he became a celebrity.

It was inevitable that a literary dweller in the French capital, reared among the traditions of a stage whose productions are classic, and a poet[Pg 22] who by both nature and environment breathed in the air of art, should turn to the drama after having won to the forefront in lyric and narrative expression. Successively he produced Deux Douleurs, Fais ce que dois, Les Bijoux de la Délivrance, Madame de Maintenon, and Le Luthier de Crémorne—the last-named an especially pleasing drama, full of that human feeling which marks Coppée in all his writings. Four volumes contain his dramatic work, all of it good, much of it brilliant.

As a novelist, Coppée left no mark upon his times—he was so easily surpassed in this field by his contemporaries. But as a writer of little prose fictions, he stands well forward among that brilliant group which includes those immortals of the short-story—Maupassant, Daudet, Mérimée, Balzac, Gautier, Loti, Halévy, Theuriet, and France.

From the work of all these masters, Coppée’s is well distinguished. The Norman Maupassant drew his lines with a sharper pencil, and by that same token an infinitely harder one. Daudet, child of Provence though he was, dipped his stylus more often in the acid of satire. Balzac chose his “cases” from classes high and low, but rarely failed to uncover with his sharp scalpel some malignant social growth. Gautier was rougher,[Pg 23] coarser, and less sympathetic, though at times we may discern in him the sudden swelling tear and tremulous lip which now and again reveal the tenderness latent in brusk men. Halévy was more idyllic and pastoral. Mérimée of all this wonderful company—to whose society other notables also come with insistent and well-sustained claims for admission—was the nearest to Coppée in the type of his work. Both knew intimately and with tender feeling the life of lowly folk—Coppée finding ever in his Paris the themes, the scenes, the types for his stories, while Mérimée’s pen was never so magic as when the romantic Corsican airs breathed about his brow. Both these master craftsmen produced a prose infused with the imagery, grace, and charm of poesy; both were masters of a style nervous, firm, condensed, and vivid.

In 1878, after having been for some years employed in the Senate Library, Coppée was appointed Guardian of the Archives of the Comédie Française. It was then that he began to produce that remarkable series of some fifty short fictions by which he is best known to us. One year after the publication of his first volume of stories, Contes en Prose (1882), he was distinguished by election to the Academy, and in 1885 he was made an officer of the Legion of Honor.

[Pg 24]

His other collections of stories are Vingt Contes Nouveaux (1883), Contes et Recits en Prose (1885), Contes Rapides (1888), Contes Tout Simples (1894), and Contes pour les Jours de Fête (1903).

In considering Coppée’s fictional work, it seems worth while to point out its varied types, and at the same time note the meaning of several short fictional forms which will be referred to frequently in this volume and in succeeding volumes of the series.

His favorite type seems to have been the tale—which is not the plotted short-story, nor yet the sketch, but rather a straightforward narration with little or no plot, and usually depending for its interest upon a longer or shorter chain of incidents. The French word conte sufficiently describes the tale, because conte means really just story, and thus the generic term includes all the shorter fictional forms. To most English readers, the term short-story means merely a story that is short, but modern usage limits the word—the compound word, to be precise—to a somewhat specialized type.

The typical short-story eludes precise definition, because it is an elastic, living thing—often the more interesting for its very disregard of an exact technical form. Certain things, however, the real short-story does possess: a single central[Pg 25] dominant incident, a single preëminent character or pair of characters, a complication (not necessarily at all involved) the resolution or untying or dénouement of that complication, and a treatment so compressed and unified as to produce a singleness of impression. Here, naturally, is much latitude, but above all the short-story must focus a white light upon one spot, upon a crucial instance, to use Mrs. Wharton’s admirable expression, and must not diffuse that light over a whole life, a series of loosely related happenings, or a general condition of affairs.

But the fictional sketch presents nothing of the organization seen in the typical short-story. It is a fragment, a detached though perhaps a complete impression, a bit of character caught in passing, a rapidly outlined picture, but not depending upon a complication and its unfolding for its interest.

Like the sketch, the tale is more easily defined than the short-story. Whether long or short, the tale—as I have just pointed out—is always the simple narration of an incident, or a succession of incidents, without regard to plot-complication and its consequent dénouement. The story of a thrilling lion-hunt, the recovery of a lost child, the adventures of a hero under strange skies, or the patient loyalty of an old servitor, might any one of[Pg 26] them be its theme—that and nothing more.

How much a fictional masterpiece suffers in translation none knows so well as he who enjoys its beauties in the original. How much more then must it lose when one attempts to rehearse its story in brief synopsis. Yet we may come to some understanding of Coppée’s typical variety by such an examination of three of his short pieces, besides “The Substitute,” which is given in full in translation.

“At Table” is one of the author’s characteristic sketches. It is about twenty-five hundred words long. Fourteen are at table, the guests of “madame la comtesse”—“four young women in full toilette, and ten men belonging to the aristocracy of blood or of merit.” With that pictorial gift which is the literary sketch-artist’s first possession, we are shown the whole scene—“jewels, decorations of honor or of nobility, the atmosphere of good living in the high hall,” the glittering table, the noiseless service, the expanding social spirit as the collation advances, the “snapping of bright words,” and everything that made the dinner “charming as well as sumptuous.”

“Now, at that same table, at the lower end, in the most modest place, a man still young ... a man of reverie and imagination ... sat[Pg 27] silent.” “He was plunged in a bath of optimism; it seemed good to him that there should be, sometimes and somewhere in the weary world, beings almost happy.” “But when the Dreamer had before him on his plate a portion of the monstrous turbot, the light odor of the sea evoked in his mind a picture of the Breton fisher folk, by grace of whose dangers this delectation came to the feasters.”

Thus his fancy wanders on, vividly rebuilding the varied scenes peopled by those whose labors, painful often and ill-requited, made possible the revelry that night. The contrast stands out, white against black, and leads at last to this mixed conclusion: Softly and stubbornly he repeats to himself as he looks once again at the guests as, replete, they arise from table:

“Yes; they are within their rights. But do they know, do they comprehend, that their luxury is made from many miseries? Do they think of it sometimes? Do they think of it as often as they should? Do they think of it?”

Rarely does Coppée approach so closely to making a preachment; but we need only to follow his gentle reflections—so far removed from haranguing, from bitterness—to feel the utter sincerity of this heart that so passionately loved “the people.”

[Pg 28]

“Two Clowns” is a sketch of a different type—less aggressively moral, its conclusion more subtly enforced, and possessing more of the narrative quality of the tale. It is a dual sketch—a sketch of contrasts.

We are standing before the tent of some strolling acrobats. To lure the bystanders to the performance a clown receives the rain of pretended buffets from the hands of the ring-master—quite in the manner we all know. Now an aged crone among the onlookers is seen to be weeping. On being questioned she wails out the story that she has recognized in this wretched clown her only son. Having robbed his master, he had been sent away to sea, the father had died, and now after having heard nothing of the scapegrace for years she discovers in the buffeted clown her only child. But suddenly the old woman realizes that she is telling the intimate sorrows of her heart to the gaping crowd, and with gesture abrupt and imperious she pushes aside her listeners and disappears in the night.

The second scene is in the Chamber of Deputies, at a sensational sitting. An orator mounts the tribune to denounce some proposed spoliation of the people. With all the arts of the demagogue—wonderfully delineated—he begins his string of ready-made phrases. He postures, he mouths,[Pg 29] he prophesies, he looses the dogs of war, “he even risks a bit of poetry, flourishes old metaphors which were worn-out in the time of Cicero,” and amidst mingled bravos and grumbles “soars like a goose,” and ends.

As we leave the Chamber we see an elderly woman of the bourgeoisie. It is the mother of the political mountebank—she is radiant and content.

“The Sabots of Little Wolff” is a typical tale, done in the manner of a legend. Never was the spirit of childhood—human and divine—more exquisitely set forth than in this wonderfully wrought story. How can it be told in other, or fewer, words than those simple and eloquent sentences of François Coppée!

“Once upon a time—it was so long ago that the whole world has forgotten the date—in a city in the north of Europe—whose name is so difficult to pronounce that no one remembers it—once upon a time there was a little boy of seven, named Wolff. He was an orphan in charge of an old aunt who was hard and avaricious, who embraced him only on New Year’s Day, and who breathed a sigh of regret every time she gave him a porringer of soup.

“But the poor little fellow was naturally so good that he loved the old woman all the same, though she frightened him greatly, and he could[Pg 30] never without trembling see the huge wart, ornamented with four gray hairs, which she had on the end of her nose.”

On Christmas eve the schoolmaster took all his pupils to the midnight mass. The winter was cold, so the lads came warmly wrapped and shod—all except little Wolff, who shivered in thin garments, and heavy wooden shoes, or sabots. “His thoughtless comrades made a thousand jests over his sad looks and his peasant’s dress,” and boasted of the wonderful times in store for them on Christmas Day. Little Wolff knew very well that his miserly aunt would send him supperless to bed, yet he innocently hoped that the Christ-child would not forget him on the morrow.

On the way out little Wolff noticed sitting in a niche under the porch a sleeping child—not a beggar child, for he was covered by a robe of white linen. But notwithstanding the cold his feet were bare—and near him lay the tools of a carpenter’s apprentice. None of the well-clad scholars heeded the child, “but little Wolff, coming last out of church, stopped, full of compassion, before the beautiful sleeping infant,” took off his right shoe, and laid it beside the child, “so the Christ-child could put something therein to comfort him in his misery.”

[Pg 31]

At home his aunt scolded him well for having given away his shoe, and scornfully she placed the other sabot in the chimney, predicting that he would find in it next morning only a rod for a whipping. And with a couple of slaps the wicked woman drove the child to bed.

But on Christmas morning little Wolff beheld in artless ecstasy both his little sabots overflowing with countless good things, so that the whole chimney was full of them. But the outcries on the street outside told them that the other children of the school had each gotten only a rod!

Finally, in “The Substitute” we have the typical short-story. Though the plot is simple, it is well balanced and marches forward with never a digression nor a false step. The characters live, the setting is adequate, and the treatment is without artificiality. The rise of Leturc from the purlieus of Paris to the moral grandeur which leads him to his final imprisonment is simple, unaffected and natural. There is not a trace of the theatric in the whole story, not a suggestion of false sentiment, not anything that mars its beauty, its symmetry, and its power.

In the midst of so much that is sordid and gross in modern fiction, how refreshing it is to read the pages of a master who could be truthful without[Pg 32] wallowing, moral without sermonizing, humorous without buffooning, and always disclose in his stories the spirit of a sympathetic lover of mankind!

[Pg 33]

(LE REMPLAÇANT)

By François Coppée

Done into English by the Editor

He was scarcely ten years old when he was first arrested as a vagabond.

Thus he spoke to the judges:

“I am called Jean François Leturc, and for six months now I’ve been with the man who sings between two lanterns on the Place de la Bastille, while he scrapes on a string of catgut. I repeat the chorus with him, and then I cry out, 'Get the collection of new songs, ten centimes, two sous!’ He was always drunk and beat me; that’s why the police found me the other night, in the tumble-down buildings. Before that, I used to be with the man who sells brushes. My mother was a laundress; she called herself Adèle. At one time a gentleman had given her an establishment, on the ground-floor, at Montmartre. She was a good worker and loved me well. She made money because she had the clientele of the café waiters, and those people use lots of linen. Sundays, she would put me to bed early to go to the ball; but week days, she sent me to the Brothers’ school,[Pg 34] where I learned to read. Well, at last the sergent-de-ville whose beat was up our street began always stopping before her window to talk to her—a fine fellow, with the Crimean medal. They got married, and all went wrong. He didn’t take to me, and set mamma against me. Every one boxed my ears; and it was then that, to get away from home, I spent whole days on the Place Clichy, where I got to know the mountebanks. My step-father lost his place, mamma her customers; she went to the wash-house to support her man. It was there she got consumption—from the steam of the lye. She died at Lariboisière. She was a good woman. Since that time I’ve lived with the brush-seller and the catgut-scraper. Are you going to put me in prison?”

He talked this way openly, cynically, like a man. He was a ragged little rascal, as tall as a boot, with his forehead hidden under a strange mop of yellow hair.

Nobody claimed him, so they sent him to the Reform School.

Not very intelligent, lazy, above all maladroit with his hands, he was able to learn there only a poor trade—the reseating of chairs. Yet he was obedient, of a nature passive and taciturn, and he did not seem to have been too profoundly corrupted[Pg 35] in that school of vice. But when, having come to his seventeenth year, he was set free again on the streets of Paris, he found there, for his misfortune, his prison comrades, all dreadful rascals exercising their low callings. Some were trainers of dogs for catching rats in the sewers; some shined shoes on ball nights in the Passage de l’Opéra; some were amateur wrestlers, who let themselves be thrown by the Hercules of the side-shows; some fished from rafts out in the river, in the full sunlight. He tried all these things a little, and a few months after he had left the house of correction he was arrested anew for a petty theft: a pair of old shoes lifted from out an open shop-window. Result: a year of prison at Sainte-Pélagie, where he served as valet to the political prisoners.

He lived, astonished, among this group of prisoners, all very young and negligently clad, who talked in loud voices and carried their heads in such a solemn way. They used to meet in the cell of the eldest of them, a fellow of some thirty years, already locked up for a long time and apparently settled at Sainte-Pélagie: a large cell it was, papered with colored caricatures, and from whose windows one could see all Paris—its roofs, its clock-towers, and its domes, and, far off, the distant line of the hills, blue and vague against the[Pg 36] sky. There were upon the walls several shelves filled with books, and all the old apparatus of a salle d’armes—broken masks, rusty foils, leather jackets, and gloves that were losing their stuffing. It was there that the “politicians” dined together, adding to the inevitable “soup and beef” some fruit, cheese, and half-pints of wine that Jean François went out to buy in a can—tumultuous repasts, interrupted by violent disputes, where they sang in chorus at the dessert the Carmangole and Ça ira.[2] They took on, however, an air of dignity on days when they made place for a newcomer, who was at first gravely treated as “citizen,” but who was the next day tutoyed,[3] and called by his nickname. They used big words there—Corporation, Solidarity, and phrases all quite unintelligible to Jean François, such as this, for example, which he once heard uttered imperiously by a frightful little hunchback who scribbled on paper all night long:

“It is settled. The cabinet is to be thus composed: Raymond in the Department of Education, Martial in the Interior, and I in Foreign Affairs.”

Having served his time, he wandered again about Paris, under the surveillance of the police, [Pg 37]in the fashion of beetles that cruel children keep flying at the end of a string. He had become one of those fugitive and timid beings whom the law, with a sort of coquetry, arrests and releases, turn and turn about, a little like those platonic fishermen who, so as not to empty the pond, throw back into the water the fish just out of the net. Without his suspecting that so much honor was done to his wretched personality, he had a special docket in the mysterious archives of la rue de Jérusalem,[4] his name and surnames were written in a large back-hand on the gray paper of the cover, and the notes and reports, carefully classified, gave him these graded appellations: “the man named Leturc,” “the prisoner Leturc,” and at last “the convicted Leturc.”

He stayed two years out of prison, dining à la Californie,[5] sleeping in lodging-houses, and sometimes in lime-kilns, and taking part with his fellows in endless games of pitch-penny on the boulevards near the city gates. He wore a greasy cap on the back of his head, carpet slippers, and a short white blouse. When he had five sous, he had his hair curled. He danced at Constant’s at Montparnasse; bought for two sous the jack-of-hearts or the ace-of-spades, which were used as [Pg 38]return checks, to resell them for four sous at the door of Bobino; opened carriage-doors as occasion offered; led about sorry nags at the horse-market. Of all the bad luck—in the conscription he drew a good number.[6] Who knows whether the atmosphere of honor which is breathed in a regiment, whether military discipline, might not have saved him? Caught in a haul of the police-net with the young vagabonds who used to rob the drunkards asleep in the streets, he denied very energetically having taken part in their expeditions. It was perhaps true. But his antecedents were accepted in lieu of proof, and he was sent up for three years to Poissy. There he had to make rough toys, had himself tattooed on the chest, and learned thieves’ slang and the penal code. A new liberation, a new plunge into the Parisian sewer, but very short this time, for at the end of hardly six weeks he was again compromised in a theft by night, aggravated by violent entry,[7] a doubtful case in which he played an obscure rôle, half dupe and half fence.[8] On the whole, his complicity seemed evident, and he was condemned to five years’ hard labor. His sorrow in [Pg 39]this adventure was, chiefly, to be separated from an old dog which he had picked up on a heap of rubbish and cured of the mange. This beast loved him.

Toulon, the ball on his ankle, the work in the harbor, the blows from the staves, the wooden shoes without straw,[9] the soup of black beans dating from Trafalgar, no money for tobacco, and the horrible sleep on the filthy camp-bed of the galley slave, that is what he knew for five torrid summers and five winters blown upon by the Mistral.[10] He came out from there stunned, and was sent under surveillance to Vernon, where he worked for some time on the river; then, an incorrigible vagabond, he broke exile and returned again to Paris.

He had his savings, fifty-six francs—that is to say, time enough to reflect. During his long absence, his old and horrible comrades had been dispersed. He was well hidden, and slept in a loft at an old woman’s, to whom he had represented himself as a sailor weary of the sea, having lost his papers in a recent shipwreck, and who wished to essay another trade. His tanned face, his calloused hands, and a few [Pg 40]nautical terms he let fall one time or another, made this story sufficiently probable.

One day when he had risked a saunter along the streets, and when the chance of his walk had brought him to Montmartre, where he had been born, an unexpected memory arrested him before the door of the Brothers’ school in which he had learned to read. Since it was very warm, the door was open, and with a single glance the passing incorrigible could recognize the peaceful school-room. Nothing was changed: neither the bright light shining in through the large windows, nor the crucifix over the desk, nor the rows of seats furnished with leaden inkstands, nor the table of weights and measures, nor the map on which pins stuck in still pointed out the operations of some ancient war. Heedlessly and without reflecting, Jean François read on the blackboard these words of the Gospel, which a well-trained hand had traced as an example of penmanship:

Joy shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons which need no repentance.

It was doubtless the hour for recreation, for the Brother professor had left his chair, and, sitting on the edge of a table, he seemed to be telling a[Pg 41] story to all the gamins who surrounded him, attentive and raising their eyes. What an innocent and gay countenance was that of the beardless young man, in long black robe, with white necktie, with coarse, ugly shoes, and with badly cut brown hair pushed up at the back. All those pallid faces of children of the populace which were looking at him seemed less childlike than his, above all when, charmed with a candid, priestly pleasantry he had made, he broke out with a good and frank peal of laughter, which showed his teeth sound and regular—laughter so contagious that all the scholars broke out noisily in their turn. And it was simple and sweet, this group in the joyous sunlight that made their clear eyes and their blonde hair shine.

Jean François looked at the scene some time in silence, and, for the first time, in that savage nature all instinct and appetite, there awoke a mysterious and tender emotion. His heart, that rude, hardened heart, which neither the cudgel of the galley master nor the weight of the watchman’s heavy whip falling on his shoulders was able to stir, beat almost to bursting. Before this spectacle, in which he saw again his childhood, his eyes closed sadly, and, restraining a violent gesture, a prey to the torture of regret, he walked away with great strides.

[Pg 42]

The words written on the blackboard came back to him.

“If it were not too late, after all?” he murmured. “If I could once more, like the others, eat my toasted bread honestly, sleep out my sleep without nightmare? The police spy would be very clever to recognize me now. My beard, that I shaved off down there, has grown out now thick and strong. One can borrow somewhere in this big ant-heap, and work is not lacking. Whoever does not go to pieces soon in the hell of the galleys comes out agile and robust; and I have learned how to climb the rope-ladders with loads on my back. Building is going on all around here, and the masons need helpers. Three francs a day,—I have never earned so much. That they should forget me, that is all I ask.”

He followed his courageous resolution, he was faithful to it, and three months afterward he was another man. The master for whom he labored cited him as his best workman. After a long day passed on the scaffolding, in the full sun, in the dust, constantly bending and straightening his back to take the stones from the hands of the man below him and to pass them to the man above him, he went to get his soup at the cheap eating-house, tired out, his legs numb, his hands burning, and his eyelashes stuck together by the plaster,[Pg 43] but content with himself, and carrying his well-earned money in the knot of his handkerchief. He went out without fear, for his white mask made him unrecognizable, and, then, he had observed that the suspicious glance of the policeman seldom falls on the real worker. He was silent and sober. He slept the sound sleep of honest fatigue. He was free.

At last—supreme recompense!—he had a friend.

It was a mason’s helper like himself, named Savinien, a little peasant from Limoges, red-cheeked, who had come to Paris with his stick over his shoulder and his bundle on the end of it, who fled from the liquor-dealers and went to mass on Sundays. Jean François loved him for his piety, for his candor, for his honesty, for all that he himself had lost, and so long ago. It was a passion profound reserved, disclosing itself in the care and forethought of a father. Savinien, himself easily moved and self-loving, let things take their course, satisfied only in that he had found a comrade who shared his horror of the wine-shop. The two friends lived together in a furnished room, fairly clean, but their resources were very limited; they had to take into their room a third companion, an old man from Auvergne, sombre[Pg 44] and rapacious, who found a way of economizing out of his meagre wages enough to buy some land in his own province.

Jean François and Savinien scarcely left each other. On days of rest they took long walks in the environs of Paris and dined in the open air in one of those little country inns where there are plenty of mushrooms in the sauces and innocent enigmas on the bottoms of the plates. There Jean François made his friend tell him all those things of which those born in the cities are ignorant. He learned the names of the trees, the flowers, the plants; the seasons for the different harvests; he listened avidly to the thousand details of a farmer’s labors: the autumn’s sowing, the winter’s work, the splendid fêtes of harvest-home and vintage, and the flails beating the ground, and the noise of the mills by the borders of the streams, and the tired horses led to the trough, and the morning hunting in the mists, and, above all, the long evenings around the fire of vine-branches, shortened by tales of wonder. He discovered in himself a spring of imagination hitherto unsuspected, finding a singular delight in the mere recital of these things, so gentle, calm, and monotonous.

One anxiety troubled him, however, that Savinien should not come to know his past.[Pg 45] Sometimes there escaped him a shady word of thieves’ slang, an ignoble gesture, vestiges of his horrible former existence; and then he felt the pain of a man whose old wounds reopen, more especially as he thought he saw then in Savinien the awakening of an unhealthy curiosity. When the young man, already tempted by the pleasures which Paris offers even to the poorest, questioned him about the mysteries of the great city, Jean François feigned ignorance and turned the conversation; but he had now conceived a vague inquietude for the future of his friend.

This was not without foundation, and Savinien could not long remain the naïve rustic he had been on his arrival in Paris. If the gross and noisy pleasures of the wine-shop always were repugnant to him, he was profoundly troubled by other desires full of danger for the inexperience of his twenty years. When the spring came, he began to seek solitude, and at first he wandered before the gayly lighted entrances to the dancing-halls, through which he saw the girls going in couples, without bonnets—and with their arms around each other’s waists, whispering low. Then, one evening, when the lilacs shed their perfume, and when the appeal of the quadrille was more entrancing, he crossed the threshold, and after that Jean François saw him change little by little in[Pg 46] manners and in visage. Savinien became more frivolous, more extravagant; often he borrowed from his friend his miserable savings, which he forgot to repay. Jean François, feeling himself abandoned, was both indulgent and jealous; he suffered and kept silent. He did not think he had the right to reproach; but his penetrating friendship had cruel and insurmountable presentiments.

One evening when he was climbing the stairs of his lodging, absorbed in his preoccupations, he heard in the room he was about to enter a dialogue of irritated voices, and he recognized one as that of the old man from Auvergne, who lodged with him and Savinien. An old habit of suspicion made him pause on the landing, and he listened to learn the cause of the trouble.

“Yes,” said the man from Auvergne angrily, “I am sure that some one has broken open my trunk and stolen the three louis which I had hidden in a little box; and the man who has done this thing can only be one of the two companions who sleep here, unless it is Maria, the servant. This concerns you as much as me, since you are the master of the house, and I will drag you before the judge if you do not let me at once open up the valises of the two masons. My poor hoard! It was in its place only yesterday; and I will tell you what it was, so that, if we find it, no one can[Pg 47] accuse me of lying. Oh, I know them, my three beautiful gold pieces, and I can see them as plainly as I see you. One was a little more worn than the others, of a slightly greenish gold, and that had the portrait of the great Emperor; another had that of a fat old fellow with a queue and epaulets; and the third had a Philippe with side-whiskers. I had marked it with my teeth. No one can trick me, not me. Do you know that I needed only two others like those to pay for my vineyard? Come on, let us look through the things of these comrades, or I will call the police. Make haste!”

“All right,” said the voice of the householder; “we’ll search with Maria. So much the worse if you find nothing, and if the masons get angry. It is you who have forced me to it.”

Jean François felt his heart fill with fear. He recalled the poverty and the petty borrowings of Savinien, the sombre manner he had borne the last few days. Yet he could not believe in any theft. He heard the panting of the man from Auvergne in the ardor of his search, and he clenched his fists against his breast as if to repress the beatings of his heart.

“There they are!” suddenly screamed the victorious miser. “There they are, my louis, my dear treasure! And in the Sunday waistcoat of[Pg 48] that little hypocrite from Limoges. Look, landlord! they are just as I told you. There’s the Napoleon, and the man with the queue, and the Philippe I had dented with my teeth. Look at the mark. Ah, the little rascal with his saintly look! I should more likely have suspected the other. Ah, the villain! He will have to go to the galleys!”

At this moment Jean François heard the well-known step of Savinien, who was slowly mounting the stairs.

“He is going to his betrayal,” thought he. “Three flights. I have time!”

And, pushing open the door, he entered, pale as death, into the room where he saw the landlord and the stupefied servant in a corner, and the man from Auvergne on his knees amid the disordered clothes, lovingly kissing his gold pieces.

“Enough of this,” he said in a thick voice. “It is I who have taken the money and who have put it in my comrade’s trunk. But that is too disgusting. I am a thief and not a Judas. Go hunt for the police. I’ll not try to save myself. Only, I must say a word in private to Savinien, who is here.”

The little man from Limoges had, in fact, just arrived, and, seeing his crime discovered, and[Pg 49] believing himself lost, he stood still, his eyes fixed, his arms drooping.

Jean François seized him violently about the neck as though to embrace him; he pressed his mouth to Savinien’s ear and said to him in a voice low and supplicating:

“Be quiet!”

Then, turning to the others:

“Leave me alone with him. I shall not go away, I tell you. Shut us up, if you wish, but leave us alone.”

And, with a gesture of command, he showed them the door. They went out.

Savinien, broken with anguish, had seated himself on a bed, and dropped his eyes without comprehending.

“Listen,” said Jean François, who approached to take his hands. “I understand you have stolen three gold pieces to buy some trifle for a girl. That would have cost six months of prison for you. But one does not get out of that except to go back again, and you would have become a pillar of the police tribunals and the courts of assizes. I know all about them. I have done seven years in the Reform School, one year at Sainte-Pélagie, three years at Poissy, and five years at Toulon. Now, have no fear. All is arranged. I have taken this affair on my shoulders.”

[Pg 50]

“Unhappy fellow!” cried Savinien; but hope was already coming back to his cowardly heart.

“When the elder brother is serving under the colors, the younger does not go,” Jean François went on. “I’m your substitute, that’s all. You love me a little, do you not? I am paid. Do not be a baby. Do not refuse. They would have caught me one of these days, for I have broken my exile. And then, you see, that life out there will be less hard for me than for you; I know it, and shall not complain if I do not render you this service in vain and if you swear to me that you will not do it again. Savinien, I have loved you well, and your friendship has made me very happy, for it is thanks to my knowing you that I have kept honest and straight, as I might always have been, perhaps, if I had had, like you, a father to put a tool in my hands, a mother to teach me my prayers. My only regret was that I was useless to you and that I was deceiving you about my past. To-day I lay aside the mask in saving you. It is all right. Come, good-by! Do not weep; and embrace me, for already I hear the big boots on the stairs. They are returning with the police; and we must not seem to know each other so well before these fellows.”

He pressed Savinien hurriedly to his breast,[Pg 51] and then he pushed him away as the door opened wide.

It was the landlord and the man from Auvergne, who were bringing the police. Jean François started forward to the landing and held out his hands for the handcuffs and said, laughing:

“Forward, bad lot!”

To-day he is at Cayenne, condemned for life, as an incorrigible.

[Pg 52]

FOOTNOTES:

[2] Revolutionary songs of '93.

[3] Tu—Thou—used only in familiar address.

[4] Police headquarters.

[5] “The California” is a cheap eating-house in Paris.

[6] In drawing lots for military service the higher numbers give exemption.

[7] Literally, climbing and breaking in.

[8] A receiver of stolen goods.

[9] Stuffed into the sabots to cushion the feet.

[10] A northwest wind on the Mediterranean.

[Pg 53]

The inflexible realist in fiction can be faithful only to what he sees; and what he sees is inevitably colored by the lens of his real self. For the literary observer of life there is no way of falsifying the reports which his senses, physical and moral, make to his own brain. If he wishes, he may make alterations in transcribing for his readers, but in so doing he confesses to himself a departure from truth as he sees it.

Pure realism, then, demands of its apostle both a faithful observation of life and a faithful statement of what he sees. True, the realist uses his artist’s privilege of selecting those facts of life which seem best suited to picturing his characters in their natures, their persons, and their careers, for he knows that many irrelevant, confusing, and contradictory things happen in the everyday lives of everyday men. So in point of practice his realism is not so uncompromising as his theories sound when baldly stated.

How near any great artist’s transcriptions of life approach to absolute truth will always be a question, both because we none of us know what is final truth, and because realists, each seeing life through his own nature, will disagree among[Pg 54] themselves just as widely as their temperaments, their predispositions, and their experiences vary. Thus we are left to the common sense for our standards, and to this common sense we may with some confidence appeal for a judgment.

Guy de Maupassant was a realist. “The writer’s eye,” he says in Sur l’Eau, “is like a suction-pump, absorbing everything; like a pickpocket’s hand, always at work. Nothing escapes him. He is constantly collecting material; gathering up glances, gestures, intentions, everything that goes on in his presence—the slightest look, the least act, the merest trifle.”

But Maupassant was more than a realist—he was an artist, a realistic artist, frank and wise enough to conform his theories to his own efficient literary practice. He saw as a realist, selected as an artist, and then was uncompromising in his literary presentation.

Here at the outstart another word is needed: Maupassant was also a literalist, and this native trait served to render his realism colder and more unsympathetic. By this I mean that to him two and three always summed up five—his temperament would not allow for the unseen, imponderable force of spiritual things; and even when he mentions the spiritual, it is with a sort of tolerant unbelief which scorns to deny the superstitious[Pg 55] solace of women, weaklings, and zealots. It was this pervading quality in both character and method which has caused his critics to class him is a disciple of naturalism in fiction. However, Maupassant’s pessimism was not so great that he could not dwell upon scenes of joy; but a preacher of hope he never was, nor could have been.

Maupassant led so individual a life, was so unnormal in his tastes, and ended his career so unusually, that common sense decides at once the validity of this one contention: his realism was marvellously true in details, but less trustworthy in its general results. His pictures of incidents were miracles of accuracy; his philosophy of life was incomplete, morbid, and unnatural.

Think how unnormal must be a spirit who could write, in the work just quoted: “I feel vibrating through me something akin to every form of animal life; I thrill with all the instincts and confused desires of the lower creatures. Like them I love the earth, not men, as you do. I love it without admiring it, without poetizing or exalting it; I love, with a profound and bestial love, at once contemptible and sacred, all that lives, all that thinks, all that we see about us,—days, nights, rivers, seas, and forests, the dawn, the rosy flesh and beaming eye of woman; for all[Pg 56] these things, while they leave my mind calm, trouble my eyes and my heart.”

But this author’s life may not be read in his works, for, unlike his contemporary, Alphonse Daudet, Maupassant’s writings are singularly barren of personal detail. True to his naturalistic school, and growing out of his method as well as by reason of his individualistic philosophy, he avoided all attempt at interpreting life and character by the lights and leadings of his own personality. And yet I have already intimated that he was biased—as similarly we all are biased—by his own nature; but it was not an artistic prejudice; rather was it the temperamental bias of a cynical eye trained to view the minute rather than the large, the sordid rather than the ideal, the pessimistic rather than the hopeful, the physical rather than the spiritual—for this was the sort of life he lived, first and last.

Persistently refusing to give to the public any record of his life, he dwelt, as it were, behind closed doors. No soul, he held, could enter into the life of another soul, so he had no real intimates, and those who called him friend and knew the frank charm of his manner discussed with him mainly impersonal themes. Thus in spite of importunities he gave no encouragement to that impertinent curiosity which avidly seizes upon[Pg 57] the details of an author’s private life and flaunts it to a gaping public. We, then, are concerned with Maupassant’s temperament and personal career only in so far as they color his work.

Born in Normandy in 1850, he passed his youth in that charming section where he has laid the scenes of many of his provincial narratives. The picturesque Norman characters, the narrow-browed country life, the colorful phases of town, market, and church, appear with intaglio clearness in a thousand wonderfully-wrought settings. The sordid and ungracious bourgeoisie with whom he came most in contact predominate in these stories, just as his strenuous days as an oarsman live again in his aquatic tales, and his life as a minor clerk in the government and his experiences as a soldier during the Franco-Prussian War are used for material in other stories. It was his later life in the Capital that gave him his knowledge of society life, and of the underworld peopled by courtesan and roué.

The gifted Flaubert, as everyone knows, left a profound impress upon his young nephew, Maupassant, who served under him a literary apprenticeship at once rigid and productive. It was Flaubert who taught the man of thirty to seek for the one inevitably fitting word, made him tear up early poems, plays, and stories,[Pg 58] taught him to suppress relentlessly all his unformed work, until, full panoplied, he sprang into being as a brilliant maker of artistic fictions.

His later years—he died by his own hand in 1893 at the age of forty-three—were darkened by the approaching madness which he so terribly pictures in “The Horla.” In Bel Ami he writes:

“There comes a day, you know, when no matter what you are looking at, you see Death lurking behind it.... As for me, for the last fifteen years I have felt the torment of it, as if I were carrying a gnawing beast. I have felt it dragging me down, little by little, month by month, hour by hour, like a house that is crumbling away.... Each step I take brings me nearer to it, every moment that passes, every breath I draw, hurries on its odious work.... Breathing, sleeping, eating, drinking, working, dreaming,—everything we do is simply dying by inches.... Now I see it so near that I often stretch out my arm to thrust it back!”

But under the shadow of this terrible phantasm as he was, latterly his cold, unsympathetic scrutiny of men and things had warmed somewhat, and his latest writings—his productive period covers only about ten intensely active years—show more gentleness, more sympathy with[Pg 59] struggling humanity. But never did he really depart from the morbid and cynical view of life, and the horror of death as the final breakdown of all things desirable, which showed so plainly in most of his fictions.

If we see but little of Guy de Maupassant’s life in his writings, it is to them we must turn to discover his temperament and his philosophy—glimpses of which we have already had.

Absolutely French, almost a typical Latin, Maupassant was not unemotional; he merely refused to allow his emotions to color the characters he delineated. He was himself a passionate pleasure-seeker, determined to extract the last drop of satisfaction from life, but he erred in thinking that one may at the same time drain the cup of mental joys and that of physical pleasures. What wonder that this vampire, in love with the blood of life, should suck final poison whence he had thought to draw only pulsing bliss. His very repressions supplied power for each fresh explosion of private excess—yet always the cold precision of his artistry grew, until the perfection of his chiselling left critics wordless. The deft maker of word-masterpieces never lost the artist in the man.

According to this warped genius, life was intended to amuse, to gratify self. Inner beauty he[Pg 60] scouted—the beauty of the seen he adored. For such a nature the ideal existed only as a foolish figment. Even ideal love he scouted, depicting with relentless fidelity the sins of a mother as discovered by her loving children, the universal laxity of the Norman peasants as condoned by complacent priests, the ravishing of every illusion, the degradation of every virtue. What other conclusion was there for so sad, so hopeless, so pitiless, so materialistic, a philosophy, than What’s the use!

But if there was little of apparent beauty in our author’s character, it is impossible not to admire his industry, his will, his passionate devotion to a perfect art, his relentless literary fidelity to truth as he saw it, his magic mastery of diction and of dialogue, his incisive though unmoral analysis of character and life, his constant advance in craftsmanship to the end. To turn out something beautiful in form was to him worth a lifetime of effort. How great would he have grown had his eyes been opened to the inner light!

I have chosen his Clair de Lune for presentation here because it more nearly approaches spiritual beauty than any other of his stories. It needs no commentary—it speaks its own beauties in tones subtly delicate yet silver clear.

[Pg 61]

(CLAIR DE LUNE)

By Guy de Maupassant

Done into English by the Editor

The Abbé Marignan bore well his title of Soldier of the Church. He was a tall priest, and spare; fanatical, perpetually in a state of spiritual exaltation, but upright of soul. His every belief was settled, without even a thought of wavering. He imagined sincerely that he understood his God thoroughly, that he penetrated His designs, His will, His purposes.

As with long strides he promenaded the garden walk of his little country presbytery, sometimes a question would arise in his mind: “Why did God create that?” And, mentally taking the place of God, he searched obstinately for the answer—and nearly always found it. It would not have been like him to murmur, in an outburst of pious humility: “O Lord, thy designs are impenetrable!” Rather might he say to himself: “I am the servant of God; I ought to know the reasons for what He does, or if I know them not, I ought to divine them.”

To him, all nature seemed created with a logic[Pg 62] as absolute as it was admirable. The “wherefore” and the “because” always corresponded perfectly. Dawn was made to gladden our waking, the day to ripen the crops, the rain to water them, the evening to prepare for slumber, and the night darkened for sleep.

The four seasons met perfectly all the needs of agriculture; and to the priest it was quite inconceivable that nature had no designs, and that, on the contrary, all living things were subjects of the same inexorable laws of period, climate, and matter.

But he did hate woman! He hated her unconscionably, and by instinct held her in contempt. Often did he repeat the words of Christ, “Woman, what have I to do with thee?” And he would add, “One might think that God Himself did not feel quite content with this one work of his hands!” To him, indeed, woman was the child twelve times unclean of whom the poet speaks. She was the temptress who had ensnared the first man, and who constantly kept up her work of damnation—she was a feeble, dangerous, and mysteriously troublous creature. And even more than her accursed body did he hate her loving spirit.

He had often felt that women were regarding him tenderly, and even though he knew himself[Pg 63] to be invulnerable, it exasperated him to recognize that need for loving which fluttered ever-present in their hearts.

In his opinion, God had created woman only to tempt man and to test him. She should never be even approached without those defensive measures which one would take, and those fears which one would harbor, when nearing a trap. In fact, she was precisely like a trap, with her lips open and arms extended towards man.

Only toward nuns did he exercise any indulgence, for they were rendered harmless by their vow. But he treated them harshly just the same, because, ever-living in the depths of their pent-up and humbled hearts, he discerned that everlasting tenderness which constantly surged up toward him, priest though he was.

Of all this he was conscious in their upturned glances, more limpid with pious feeling than the looks of monks; in the spiritual exaltations in which their sex indulged; in their ecstasies of love toward Christ, which made the priest indignant because it was really woman’s love, carnal love. Of this detestable tenderness he was conscious, too, in their very docility, in the gentleness of their voices when they addressed him, in their downcast eyes, and in their submissive tears when he rudely rebuked them.

[Pg 64]

So he would shake his cassock when he left the convent door, and stride off, stretching his legs as if fleeing before some danger.

Now the Abbé had a niece who lived with her mother in a little house near by. He was determined to make of her a sister of charity.

She was pretty, giddy, and a born tease. When he preached at her, she laughed; and when he became angry with her, she kissed him vehemently, pressing him to her bosom, while he would instinctively seek to disengage himself from this embrace—which, all the same, gave him a thrill of exquisite joy, awaking deep within his soul that feeling of fatherhood which slumbers in every man.

Often as they walked together along the footpaths through the fields, he would talk with her of God, of his God; but she scarcely heard him, for she was looking at the sky, the grass, the flowers, with a joy of life which beamed from her eyes. Sometimes she would dart away to catch some flying creature, crying as she brought it back: “See, my uncle, how pretty it is; I should like to kiss it.” And that passion to kiss insects, or lilac flowers, disturbed, irritated, and repelled the priest, who recognized even in that longing the ineradicable love which blooms perennial in the heart of woman.

[Pg 65]

And now one day the sacristan’s wife, who was the Abbé Marignan’s housekeeper, cautiously told him that his niece had a lover!

He was dreadfully shocked, and stood gasping for breath, lather all over his face, for he was shaving.

When at length he was able to think and speak, he cried: “It is not true. You are lying, Mélanie!”

But the peasant woman laid her hand over her heart: “May our Lord judge me if I am lying, monsieur le curé. I tell you she goes out to him every night as soon as your sister is in bed. They meet each other down by the river. You need only go there between ten o’clock and midnight to see for yourself.”

He stopped rubbing his chin and began pacing the room violently, as was his custom in times of serious thought. When at length he did try to finish his shaving he cut himself three times, from nose to ear.

All day long he was silent, though almost exploding with indignation and wrath. To his priestly rage against the power of love was now added the indignation of a spiritual father, of a teacher, of the guardian of souls, who has been deceived, robbed, and trifled with by a mere child. He felt that egotistical suffocation which[Pg 66] parents experience when their daughter tells them that she has selected a husband without their advice and in defiance of their wishes.

After dinner he tried to read a little, but he could not—he grew more and more exasperated. When the clock struck ten, he grasped his cane, a formidable oaken club which he always carried when he went out at night to visit the sick. With a smile he examined this huge cudgel, gripped it in his solid, countryman’s fist, and flourished it menacingly in the air. Then, suddenly, with grinding teeth, he brought it down upon a chair-back, which fell splintered to the floor.

He opened his door to go out; but paused upon the threshold, surprised by such a glory of moonlight as one rarely sees.

And as he was endowed with an exalted soul of such a sort as the Fathers of the Church, those poetic seers, must have possessed, he became suddenly entranced, moved by the grand and tranquil beauty of the pale-faced night.

In his little garden, all suffused with the tender radiance, his fruit-trees, set in rows, outlined in shadows upon the paths their slender limbs of wood, scarce clothed with verdure. The giant honeysuckle, clinging to the house wall, exhaled its delicious, honeyed breath—the soul of perfume seemed to hover about in the warm, clear night.

[Pg 67]

He began to breathe deep, drinking in the air as drunkards drink their wine; and he walked slowly, ravished, amazed, his niece almost forgotten.

When he reached the open country he paused to gaze upon the broad sweep of landscape, all deluged by that caressing radiance, all drowned in that soft and sensuous charm of peaceful night. Momently the frogs sounded out their quick metallic notes, and distant nightingales added to the seductive moonlight their welling music, which charms to dreams without thought—that gossamer, vibrant melody born only to mate with kisses.

The Abbé moved on again, his courage unaccountably failing. He felt as though he were enfeebled, suddenly exhausted—he longed to sit down, to linger there, to glorify God for all His works.

A little farther on, following the winding of the little river, curved a row of tall poplars. Suspended about and above the banks, enwrapping the whole sinuous course of the stream with a sort of light transparent down, was a fine white mist, shot through by the moon-rays, and transmuted by them into gleaming silver.

The priest paused once again, stirred to the deeps of his soul by a growing, an irresistible feeling of tenderness.

[Pg 68]

And a doubt, an undefined disquietude, crept over him; he discerned the birth of one of those questions which now and again came to him.

Why had God made all this? Since the night was ordained for slumber, for unconsciousness, for repose, for forgetfulness of everything, why should He make it lovelier than the day, sweeter than dawn and sunset? And that star, slow-moving, seductive, more poetic than the sun, so like to destiny, and so delicate that seemingly it was created to irradiate things too subtle, too refined, for the greater orb—why was it come to illuminate all the shades?