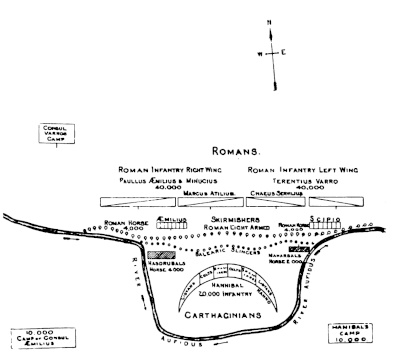

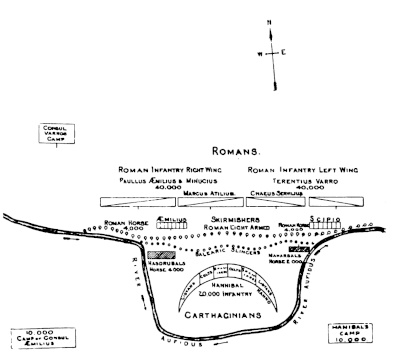

Showing the distribution and Number of the Various Troops Engaged

BY

LIEUT. COL. ANDREW HAGGARD, D.S.O.

Author of

“Tempest Torn,” “Under Crescent and Star,” etc., etc.

LONDON

HUTCHINSON & CO.

PATERNOSTER ROW

1898

TO HER ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS LOUISE,

MARCHIONESS OF LORNE.

Madam,

Surely never, in the history of the world, have events more romantic been known than the career of Hannibal and of his eventual conqueror, the youthful Scipio. Therefore, under the title of “Hannibal’s Daughter,” it has been my humble effort to present to the world in romantic guise such a story as may impress itself upon the minds of many who would never seek it for themselves in the classic tomes of history.

Having been commenced on the actual site of Ancient Carthage, the local colouring of the opening chapters may be, with the aid of history, relied upon as being correct. Throughout the whole work, moreover, the thread of the story has been interwoven with a network of those wonderful feats that are so graphically recorded for us in the pages of Polybius and Livy.

To Your Royal Highness, with the greatest respect, I have the honour to dedicate my work. Should there appear to be aught of art in the manner in which I have attempted to weave a combination of history and romance, may I venture to hope that a true artist like Your Royal Highness, of whose works the nation is justly proud, may not deem the results of my efforts unworthy.

I have the honour to be,

Madam,

Your most obedient servant,

ANDREW C. P. HAGGARD.

Alford Bridge, Aberdeenshire, May, 1898.

On a point of land on the Tœnia, a hundred paces or so to the south of the canal connecting the sea with the Cothon or double harbour of Carthage, stood a palatial residence. Upon the balcony, which ran completely round the house on the first storey, stood a man gazing steadily across the gulf towards the north-east, past the end of the Hermæan Promontory, to the left, of which the distant Island of Zembra alone relieved the monotony of the horizon. His face was grave, and his short hair and beard were slightly grey, but he was evidently a man from whom the fire of youth had not yet departed. His eye was the eye of one born to command; his straight-cut, sun-burned features told the tale of many campaigns. Near him, on a stool covered with a leopard skin, was carelessly thrown a steel helmet richly incrusted with gold, and with the crest and the crown deeply indented, as if from recent hard usage. The golden crest was in one place completely divided by a sword cut, the brighter colour of the gold within the division plainly showing that the blow had been but lately delivered. On the floor of the balcony, at the foot of the stool, lay a long straight sword. Although the hilt was of ivory, and the scabbard of silver inlaid with gems, the blood-stains on the former and the absence of many of the gems from their sockets, told that this was no fair-weather weapon for state occasions, but a lethal blade which had been borne by its owner in the brunt of many a combat. Only, the armour which the warrior wore—consisting as it did merely of a bright steel breast-piece, upon the breast of which was emblazoned in gold a gorgeous representation of the sun, the emblem of the great god Baal or Moloch, and the back of which was similarly inlaid with the two-horned moon, the attribute of the glorious Astarte, Queen of Heaven, and further studded with golden stars, the emblems of all the other and lesser divinities—seemed on first appearance as if more intended for the court than the camp. A closer examination, however, revealed the fact that this also was no mere holiday armour, for it, too, bore severe marks of ill-usage. The warrior’s arms were bare from the elbow downwards, save for a couple of circlets of gold upon each wrist, which from their width seemed more intended for defence than ornament. Beneath the armour he wore a bright toga of pure white cloth, the lower part falling in a kilted skirt below the knee, being adorned with a narrow band of Tyrian purple. Upon his feet he wore cothurns or sandals strongly attached with leather thongs, the thongs being protected with bright chain mail. Some steel pieces for the protection of the thigh and knee were lying close at hand.

Such was the attire of the great General Hamilcar Barca, as with an ever-deepening frown upon his anxious brow, he gazed sternly and steadily in deepest reverie across the sea.

At length his reverie seemed to be broken.

“Why gaze thus towards Sicily,” he muttered; “why dream of vengeance upon the hated Romans, who now occupy from end to end of that fair isle, where, for many years, by the grace of Melcareth, the invisible and omnipotent god, I was able with my small army of mercenaries to deal them so many terrible and crushing blows?

“Have they not almost as much cause to hate and to dread me, who did so much to lower their pride and wipe out the memory of their former victories? Did I not brave them for years from Mount Ercte, descending daily like a wolf from the mountain crest, to ravage the country in front of their very faces in strongly-fortified Panormus, from the shelter of whose walls, for very fear of my name, they scarcely dared to stir, so sure were they that their armies would be cut to pieces by Hamilcar Barca?

“Did I not firmly establish myself in Mount Eryx, half-way up its slope in the city on the hill, and there for two years, despite a huge Roman army at the bottom, and their Gallic allies holding the fortified temple at the top, snap my fingers at them, ay, laugh them to scorn and destroy them by the thousand? For all that time, was not their gold utterly unable to buy the treachery of my followers—were not their arms utterly futile against my person? Did they not indeed find to their cost that I was indeed the Hamilcar my name betokens—him whom the mighty Melcareth protects?”

Proudly glancing across the sea with a scornful laugh, he continued:

“Oh, ye Romans! well know ye that had not mine own countrymen left me for four long years without men, money, or provisions, Sicily had even now been mine. Oh, Prætor Valerius! what was thy much boasted victory of the Œgatian Islands over the Admiral Hanno but the conquest of a mere convoy of ill-armed cargo vessels, whom mine economical countrymen were too parsimonious to send to my relief under proper escort. Where was then thy glory, Valerius? And thou, too, Lutatius Catulus? how did I receive thy arrogant proposals that my troops should march out of Eryx under the yoke? I, a Hamilcar Barca, march out under the yoke!” The General’s swarthy cheek reddened at the thought. “Did not I but laugh in thy beard and lay my hand upon this sword—which I now lift up and kiss before heaven,” he raised and kissed the blood-stained hilt. “Did not I, even as I do now, but simply bare the well-known blade,” here he drew it from its sheath, “and thou didst fall and tremble before me, and in thine anxiety to rid Sicily of me didst willingly take back thine insult and offer to Hamilcar and all his troops the full and free liberty to march out with all the honours of war? Ah!” he continued, stretching forth his sword menacingly across the sea, “for all that it hath been mine own countrymen who were the main cause of my downfall, I yet owe thee a vengeance, Rome, a vengeance not for mine own but for my country’s sake, and, with the help of the gods, in days not long to come, those of my blood shall redden the plains and mountains of Europe with the terrible vengeance of the Barcine sword.”

The General returned his sword to its sheath with an angry clang, then striding across the wide balcony to where it overlooked a beautiful garden on the other side of the house, he shouted loudly:

“Hannibal, Hannibal!”

There was no reply, but down beneath the shelter of the fig trees Hamilcar could plainly perceive three little boys engaged in a very rough game of mimic warfare. They were all three armed with wooden swords and small shields of metal. One of them was up in a fig tree and striking downwards at the head of one who stood upon the crown of a wall; while the third boy, who stood below the wall, was striking upwards at his legs. The din of the resounding blows falling upon the shields was so great that the boy at first did not hear.

“Hannibal, come hither at once,” cried out his father again in louder tones.

Looking up and seeing his father, the boy on the wall threw down his shield, a movement which was instantly taken advantage of by each of the two other boys to get a blow well home. He did not, however, pause to retaliate, but crying out, “That will I revenge later,” threw down his sword also and rushed into the house and up to the balcony, for even at his early age the boy had been taught discipline and instant obedience, and he knew better than to delay. He appeared before his father all out of breath and with torn clothing. Notwithstanding that his forehead was bleeding from the result of the last cut which had been delivered by the boy in the tree, he did not attempt to wipe the wound, but with cast-down eyes and hands crossed over his breast, silently awaited his father’s commands.

“What wast thou doing in the garden, Hannibal?”

“Waiting until Chronos the slave could take me up to see the burnt sacrifice to Baal of the mercenaries whom thou hast conquered,” he answered—then added excitedly, “Matho, who murdered Gisco and his six hundred after mutilating them first, is to be tortured, thou knowest, oh, my father, Chronos told me so, and I am going to see it done.”

Hamilcar frowned.

“Nay, it is not my will that thou shalt go to see Matho tortured and burnt; now, what else wast thou doing down there?”

The boy’s face fell; he did not like to be deprived of the pleasure of seeing Matho tortured first and burned afterwards, for, boy as he was, he knew that if ever man in this world deserved the torture, that man was this last surviving chief of his father’s revolted mercenaries.

But he made no protest at the deprivation of his expected morning’s amusement, answering his father simply.

“I was playing with my brothers Hasdrubal and Mago at thine occupation of the City on Mount Eryx, oh! my father. Mago was up in the tree and represented the Gauls who had deserted and joined the Romans. Hasdrubal was down below and took the place of the Roman Army.”

“And thou wast in thy father’s place between the two, and like thy father himself, hast been wounded,” replied Hamilcar, smiling grimly. “Come, wipe thy face, lad, and tell me why didst not thou, being the strongest, take the part of the Romans at the bottom of the hill?”

Fiercely the youth raised his head, and, looking his father straight in the face, replied:

“For two reasons, my father. First, I am much stronger than Hasdrubal, and the war would have been too soon over; secondly, I hate the Romans, and for nothing in the world would I represent them even in play.”

“Ah! thou hatest the Romans! And wilt thou then fight them one day in earnest and avenge the torrents of Carthaginian blood they have caused to flow, the hundreds of Carthaginian cities whose inhabitants they have put to the sword; avenge, too, our defeat and loss of forty-one elephants before Heraclea; the sacking of Agrigentum and enslavement of 25,000 of its citizens; the terrible loss of three hundred warships at Ecnomos; the invasion of Carthaginia by Regulus; his sacking and burning of all the fair domain between here and Clypea, across yonder Hermæan Promontory; the capture by Cœcilius Metellus before Panormus of 120 elephants from Hasdrubal, all of them slaughtered in cold blood as a spectacle for the Roman citizens in the Roman circus; the fight at—”

“Stop, father, stop!” cried the young Hannibal, stamping his foot. “I can bear no more. By thy sword here, which I can even now draw—see I do so—I swear to fight and avenge all these disasters. By the favour of the great god Baal, whose name I bear, I will wage war against them all my life as soon as ever I am old enough to carry arms.”

“Good,” said his father, “thou art a worthy son of Hamilcar, and this very day shalt thou swear, not in the bloody temple of Moloch, but in the sacred fane of Melcareth, the god of the city, the god of thy forefathers in Tyre, and the god of the divine Dido, the foundress of Carthage, that never wilt thou relax the hatred to the Romans thou hast even now sworn by thy father’s sword. Never shalt thou, whilst life lasts thee, cease to fight for thy native city, thy native country. Look forth, my lad, upon all thou canst see now, and say, is it not a fair domain? Let all that lies before thine eyes now sink down deep into the innermost recesses of thy memory, for soon I shall take thee hence; but I would not have thee, when far away, forget the sacred city for whose very existence thou and I must fight. When thou hast gazed thy fill upon all that lies before us, thou must perform thine ablutions, arrange thy disordered dress, and then thou shalt accompany me, not to see the sacrifice of the mercenaries in the pit of fire before the brazen image of Moloch, but to make thy vow in the temple of the invisible and all-pervading mighty essence of godhead, the eternal Melcareth.”

The terrible war, known as the inexpiable or the truceless war, was just at an end, after three years’ duration. The mercenaries who had served so faithfully under Hamilcar in Sicily had by the bad faith of the Carthaginian Government, headed by Hamilcar’s greatest enemy, Hanno, been driven to a revolt to try and recover the arrears of pay due to them for noble services for years past. When the effete Hanno, after a first slight success, had allowed his camp to be captured, the Government, at the last gasp, had begged Hamilcar to fight against his own old soldiers. For the sheer love of his country, he had, although much against the grain, consented to do so. But the towns of Utica, the oldest Phœnician town in Africa, and of Hippo Zarytus were joining in the revolt; the Libyans and Numidians had risen en masse to join the revolutionists, and the Libyan women, having sold all their jewellery, of which they possessed large quantities, for the sake of the revolted mercenaries, there was soon so much money in the rebel camp that the very existence of Carthage itself was at stake. Therefore, although Hamilcar well knew that all the mercenaries, whether Libyans or Ligurians, Balearic Islanders, Greeks, or Spaniards, were personally well disposed to himself, he had been forced to take up arms against them.

Under Spendius, a Campanian slave, and Matho, an African in whom they had formerly placed great trust, the rebels had gained various successes, and, on visiting them in their camp, had treacherously made prisoner of Gisco, a general in whom they had previously expressed the greatest trust, and whom they had asked to have sent to them with money to arrange their difficulties. Hamilcar had been at first much hampered by his enemy, Hanno, an effeminate wretch, being associated in the command with himself; but when the Carthaginians found that, by leaving Hanno to hamper Hamilcar, with all these well-trained soldiers against them, they had got the knife held very close to their own luxurious throats, they removed Hanno, and left the patriotic Hamilcar in supreme military command. Their jealousies of him would not have allowed the aristocracy and plutocracy to have done so much for the man whom they had deserted for so long in Sicily had they not known their own very existence to be at stake. For they ran the risk of being killed both by the Libyans and mercenaries outside, and by the discontented people inside the walls.

When Hamilcar assumed supreme command, the war had very soon commenced to go the other way. He forced the easy, luxurious Carthaginian nobles to become soldiers, and treated them as roughly as if they had been slaves. And he made them fight. He got elephants together; he made wonderful marches, dividing the various rebel camps; he penned them up within their own fortified lines. Many deserted and joined him; many prisoners whom he took he released; a great African chief named Naravas came over to his side. All was going well for Carthage when Spendius and Matho mutilated and murdered the wretched General Gisco and his six hundred followers in cold blood. After that no more of their followers dared to leave them for fear of the terrible retaliation that they knew awaited them. But how Spendius and all his camp were at length penned up and reduced to cannibalism, eating all their prisoners and slaves, how Spendius and his ten senators were taken and crucified, while Matho, at the same time issuing from Tunis, took and crucified a Carthaginian general and fifty of his men, and how at length, after slaughtering or capturing the 30,000 or 40,000 remaining rebels, Hamilcar took Matho himself prisoner, are all matters of history.

On the morning of the opening of our story, there was to be a terrible sacrifice offered up to the great Baal Hammon, the sun god Moloch, the Saturn of the Romans: the terrible monster to whom in their hours of distress the Carthaginians were in the habit of offering up at times their own babies, their first-born sons, or the fairest of their virgins, whose cruel nuptials consisted not in being lighted with the torch of Hymen, but in being placed bound upon the outstretched, brazen, red-hot hands of the huge image, from whose arms, which sloped downwards, they rolled down into the flaming furnace at his feet. And fathers and mothers, sisters and brothers, yea, even the very lovers of the girls, looked on complacently, thinking that in thus sacrificing their dearest and their best to the cruel god, they were consulting the best interests of their country in a time of danger. Nor were the screams of the victims, many of whom were self-offered, allowed to be heard, for the drums beat, the priests chanted, and the beautiful young priestesses attached to the temple danced in circles around, joining the sound of their voices and their musical instruments to the crackling of the fire and the rolling of the drums.

When Hamilcar bid his boy, Hannibal, look forth upon the city before him, on the sea in front and behind him, and upon the country around, it was a lovely morning in early summer. The weather was not yet hot; there was a beautiful north-west breeze blowing down the Carthaginian Gulf straight into the boy’s face, tossing up little white horses on the surface of the sea, of which the white-flecked foam shone like silver on its brilliantly green surface. Across the gulf, upon whose bosom floated many a stately trireme and quinquireme, to the east side arose a bold range of rugged mountains with steep, serrated edges. Turning round yet further and facing the south, the young Hannibal could see the same mountain range, dominated by a steep, two-horned peak, sweeping round, but gradually bearing back and so away from the shores of the shallow salt water lake then known as the Stagnum, now called the Lake of Tunis. This lake was separated, by the narrow strip of land called the Tœnia, from the Sirius Carthaginensis, or Gulf of Carthage, upon the extremity of which is now built the town of Goletta. There was in those days, as now, a canal dividing this isthmus in two, and thus giving access for ships to Tunis, a distance of ten miles from Carthage, at the far end of the Tunisian lake.

Turning back again and looking to the north and north-west, Hannibal saw stretching before him the whole noble City of Carthage, of which his father’s palace formed one of the most southern buildings within the sea wall. Close at hand were various other palaces, with gardens well irrigated and producing every kind of delicious fruit and beautiful flower to delight the palate or the eye. Here waved in the breeze the feathery date palm, the oleander with its wealth of pink blossom, the dark-green and shining pomegranate tree with its glorious crimson flowers. Further, the fig, the peach tree, the orange, the lemon, and the narrow-leaved pepper tree gave umbrageous shelter to the winding garden walks. Over the cunningly-devised summer-houses hung great clusters of blue convolvulus or the purple bourgainvillia, while along the borders of plots of vines gleaming with brilliant verdure, clustered, waist-high, crimson geraniums and roses in the richest profusion. Between these palaces lay stretched out the double harbour for the merchant ships and war ships, a canal forming the entrance to the one, and both being connected with each other. The harbour for the merchant ships was oblong in shape, and was within a stone’s throw of the balcony upon which the boy was standing. The inner harbour was perfectly circular, and surrounded by a fortification; and around its circumference were one hundred and twenty sets of docks, the gates of each of which were adorned with beautiful Ionic pillars of purest marble.

In the centre of this cup, or cothon as it was called, there was an island, upon which was reared a stately marble residence for the admiral in charge of the dockyards, and numerous workshops for the shipwrights. All were designed and built with a view to beauty as well as utility.

For that day only, the clang of hammers had ceased to be heard, and all was still in the dockyards, for there was high holiday and festival throughout the whole length and breadth of the City of Carthage on the glad occasion of the intended execution, by fire, of Matho and the remaining rebels who had not fallen by the sword in the last fight at Tunis.

Just beyond the war harbour, there was a large open place called the Agora, and a little beyond and to the left of it Hannibal could descry the Forum placed on a slight elevation. It was a noble building, surrounded by a stately colonnade of pillars, the capitals of which were ornamented in the strictly Carthaginian style, which seemed to combine the acanthus plant decoration of the Corinthian capital, with the ram’s horn curves of the Ionic style. Between the pillars there stood the most beautiful works of art, statues of Parian marble ravished in the Sicilian wars, or gilded figures of cunning workmanship of Apollo, Neptune, or the Goddess Artemis, being the spoils of Macedon or imported from Tyre. The roof of the Forum was constructed of beautiful cedar beams from Lebanon, sent as a present by the rulers of Tyre to their daughter city, and no pains or expense had been spared to make the noble building, if not equal in grandeur, at any rate only second in its glorious manufacture to the magnificent temple of Solomon, itself constructed for the great king by Tyrian and Sidonian workmen.

A couple of miles away to the left could be seen the enormous triple fortification stretching across the level isthmus which connected Carthage, its heights and promontories, with the mainland. This wall enclosed the Megara or suburbs, rich with the country houses of the wealthy merchant princes. It was forty-five feet high, and its vaulted foundations afforded stabling for a vast number of elephants. It reached from sea to sea, and completely protected Carthage on the land side. Between the city proper and this wall beyond the Megara, everywhere could be seen groves of olive trees in richest profusion, while between them and the frequent intervening palaces, were to be observed either waving fields of ripening golden corn, or carefully cultivated vegetable gardens, well supplied with running streams of water from the great aqueduct which brought the water to the city from the mountains of Zaghouan sixty miles away.

To the north of the Forum and beyond the Great Place, the city stretched upwards, the width of the city proper, between the sea and the suburbs, being only about a mile or a mile and a half. It sloped upwards to the summit of the hill of the Byrsa or Citadel, hence the boy Hannibal, from his position on the sea level in rear of the harbours, was able to take in, not only the whole magnificent coup d’œil of palaces and temples, but also that of the high and precipitous hill forming Cape Carthage, which lay beyond it to the north, whose curved and precipitous cliffs enclosed on the eastern side a glittering bay, wherein were anchored many vessels of merchandise.

The summit of this mountain was, like the suburbs of the Megara to the west of the city, studded with the rich country dwellings of the luxurious and ease-loving inhabitants of Carthage.

But it was not on the distant suburbs that the lad fixed his eager gaze, it was on the gleaming city of palaces itself. Here, close at hand on the right, he could see the temple of Apollo with its great golden image of the god, gleaming between the open columns in the morning sun. Further away appeared the mighty and fortified buildings of the temple of Ashmon or Æsculapius. To the left of the city the fanes of Neptune, Diana, and Astarte glittered in the sun, while occupying the absolute centre of the town, and standing apart in a large and now crowded open space, was clearly visible the huge circular temple of the awful Sun god—Saturn, Baal Hammon, or Moloch. The drums and trumpets loudly sounding from the vicinity of this temple, and the wreaths of smoke winding up between the triple domes plated with solid gold, told that the terrible sacrifices had already begun. Indeed, the yells of execration of the myriads of brightly-robed populace, most of them women, as victim after victim was dragged forward by the priests and thrown upon the dreadful sloping arms of the god, a sight Hannibal could easily observe between the rows of columns, often nearly drowned the blare of the trumpets and the rolling of the drums.

Well, indeed, might they scream, these women of Carthage, for owing to the cruelties and massacres of those upon whom they were now wreaking their vengeance, all who had been their husbands or lovers were gone. There were now scarcely any men left. Thus they saw themselves condemned either to a perpetual virginity, with no hopes of ever knowing the joys of motherhood, or fated at the best to a share with many other women in the household of some rich and elderly noble, since polygamy had been recently decreed as a means of repopulating the State. All the young men remaining alive, Hamilcar had enrolled in his army, and although a few of the more luxurious and ease-loving might leave him and remain in Carthage, that army was, so rumour said, about to start with him and the flower of Carthaginian manhood for unknown battle-fields, whence it was improbable that they would ever return. Thus, the older women screamed and yelled with fury at the loss of husbands or sons, and the young women screamed with rage at the loss of the once possible husbands, who never had been and never could be theirs. Yet, all alike, having put off their mourning for the day, were gaily attired for joy at the burning alive of their enemies. They had even adorned their raven locks with the brilliant crimson flowers of the pomegranate, as red as their own red lips, or the blood which had been shed in torrents by Spendius and Matho, and which was again to flow that very day on this joyful occasion of revenge.

Leading from the harbours and the Great Place up through the town to all these temples were three streets—the Vicus Salutaris, on the right, leading to the temple of Æsculapius; the Vicus Satyrnis, in the centre, leading to the great brazen god Moloch; and to the left, the Vicus Venerea or Venus Street, leading to the temple of the Carthaginian Venus and Juno in one; Tanais, Tanith, or Astarte, the Goddess of Love and the Queen of Heaven combined. These last two streets swept round on either side of the hill of the Byrsa or Citadel, and it was on this hill that the eye of the youthful Hannibal chiefly rested, for within and above its walls he could see on the summit of the hill the temple of Melcareth, the unknown and invisible god of whom no image had ever been made. Melcareth was the great Spirit of life and the protector of his father, before whom he was to register his vow.

Plainly built of white marble, in simple but solemn simplicity, it was surrounded with plain Doric columns of Numidian marble. This very plainness made the exterior of the building more impressive; and as it occupied the highest point in the whole city, the boy could see it clearly.

At length, with a sigh, he took one last lingering look all round, from the mountains of the Hermæan Promontory to the Gulf, from the Gulf to Cape Carthage, and to the city from the hill of the Catacombs, round and past the triple wall enclosing the Megara, away to the white buildings of Tunis in the distance, and to the lake near at hand.

“I have seen it all, my father,” he said at length; “not a headland nor a house, not a tree nor a temple, will ever fade away again from my memory. It is all engraven on my heart.”

“It is well,” said Hamilcar; “now go and prepare thyself to accompany me to the temple of Melcareth; thou shalt accompany me upon my elephant, for I shall go in state. Here, Maharbal! Imlico! Hanno! Gisco!”

A crowd of officers rushed in from the ante-chambers, where they were waiting; the great General gave directions about the ceremony that was to take place, and orderlies and messengers were soon galloping in every direction.

An hour later, a gorgeous procession started from the General’s palace; for on this occasion Hamilcar, well knowing the hatred and jealousy with which he was regarded by the other Suffete or Chief Magistrate, Hanno, and, indeed, by more than half of the Council of one hundred senators, the real holders of power in ordinary times, had determined for once to assert the power which, in view of his recent victories, he knew that he, and he alone, held in the city. Being a great general, and just now, moreover, a victorious general, he determined that, since fortune and his own ability had for the moment placed him at the top of the tree, no sign of weakness on his own part should give to his enemies in the State the opportunity of pulling him down again from his pedestal. He had an object in view, and until he had obtained that object and left Carthage with almost regal powers over the army that he had got together, he was fully determined to maintain his own potent position by all the force at his command.

It was a whole army with which he set forth to pay his homage to the god Melcareth on that eventful June morning.

On the Great Place, just beyond the Forum, and about half a mile away, were massed, in two lines, forty war elephants fully accoutred with breastplates formed of scales of brass coated with gold. On the back of each elephant was a wooden tower containing four archers, whose burnished casques and breastplates glittered in the sun, also musicians carrying trumpets and horns. In rear of them and in front of the Forum itself was drawn up a body of a thousand Numidian cavalry, under the Chief Naravas, who, with a gold circlet round his head, which was studded with ostrich plumes, headed their van. Naravas, like all his followers, bestrode a magnificent white barb, without either saddle or bridle; the ornamental saddle cloth of golden embroidery, fastened by a cinglet, being merely for show, for the Numidians had no need for either saddles or bridles, but guided their horses with their knees. The hoofs of the horses were gilded, and their manes and tails had been newly stained with vermilion. Altogether, this band of Numidian cavalry formed a remarkable sight. The chief himself and all his men held a barbed dart in each hand, while a sheath or quiver containing other darts hung upon their left breasts. On the right side each carried a long, straight sword.

Following Naravas and his cavalry, the whole street up to Hamilcar’s dwelling was filled with the soldiers of the “Sacred Band”—the élite of Carthage. This corps was comprised only of those belonging to the richest and noblest families, and they more than equalled in valour and determination the fiercest of the mercenaries against whom they had been lately fighting. Their armour was of the most gorgeous description; it seemed literally made of gold; while necklaces of pearls and earrings of precious stones adorned their persons. On their fingers they wore gold rings in number equalling the battles they had been in—one for each fight; but many of them present on this eventful morn had taken part in so many fights under Hamilcar that they were unable to carry all their rings on their fingers. They had therefore attached them by smaller rings of strong metal to the edges of their shields, which shields were inlaid with gold and precious stones. With each maniple, or company of a hundred of the Sacred Band, was present—in rear—a hundred Greek slaves. These slaves wore collars of gold, were gorgeously attired, and bore in state the golden wine goblets from which the Sacred Band were wont to drink. Alone in the army the Sacred Band were allowed to drink wine when on service; for other soldiers to do so was death. Woe betide any soldier of any other corps who should be discovered in purloining or even drinking from one of these sacred cups. Crucifixion was the least of the evils that he might expect to befal him.

The Sacred Band were commanded at that time by Idherbal, the son of Gisco, the general who had been so barbarously murdered by Spendius and Matho. He was a noble-looking young man, mounted on a splendid chestnut barb. All his officers were however, like the men, dismounted. Originally two thousand five hundred in number, there now only remained eighteen hundred of Idherbal’s troops.

Eight hundred of these filled the streets from the rear of the Numidian cavalry to Hamilcar’s palace, the remaining thousand were massed behind the palace, and they in turn were to be followed by over three thousand Gauls who had, fortunately for themselves, immediately left the insurgent camp and joined Hamilcar on the first occasion of his advancing against the mercenaries. These Gauls were naked to the waist and carried long straight swords.

On each side of the road leading up to the citadel, for the whole distance at intervals of a few paces, were posted alternately “hastati” or spearmen, and cavalry soldiers to keep back the crowd. These were all Iberians or Spaniards, some of whom had come across with Hamilcar himself when he had left Sicily, while others had through emissaries been since recruited. They were all absolutely faithful to Hamilcar. The horses of the Spanish cavalry were saddled and bridled, and the soldiers of both horse and foot alike wore under their armour white tunics edged with purple. The cavalry carried a long straight sword, adapted either to cutting or thrusting, and a small shield on the left arm. There were about two thousand in number of these guards placed to line the streets.

With the exception of the Sacred Band of nobles, upon whom Hamilcar could perfectly rely, and whom, for State reasons, he wished to have that day much en evidence in his train, none of these troops, nearly eight thousand in number, were Carthaginians. Orders had been previously given that all the guard duties at the outposts and round the city walls were that day to be taken by the recently raised Carthaginian troops. All the guards within the city were therefore held by troops to whom, as to these soldiers of his magnificent escort—Hamilcar’s person was as sacred as that of a god.

Between the first and second detachments of the Sacred Band, in front of the door of the palace, stood Hamilcar’s magnificent state elephant, Motee, or Pearl—the highest in all Carthage. It was of great age, and had been brought from India through Persia. The Mahout, or driver, who was an Indian, was dressed in a crimson and gold turban, with a loose silken jacket and pantaloons of the same colours. The elephant, Motee, was protected on the forehead, neck, head, and shoulders with plates formed of golden scales, while over all its body hung a cloth of the most gorgeous Tyrian purple, edged with gold. Round its legs, just above the feet, were anklets of silver, to which were attached bells like sledge bells, made of bronze, gilded. The tusks of the elephant were gigantic in size, and were painted in wide rings with vermilion, leaving alternate rings showing off the white ivory, the points of the tusks being left of the natural colour. Upon the back of the elephant was a car of solid silver, each side being formed of a crescent moon. It was constructed so as to contain two or three persons only. The front and rear of this car were formed of large shields, made so as to represent the sun, being of gold, and having a perfectly smooth surface in the centre, which was burnished as a mirror. Radiating lines of rougher gold extending to the edges of the shields made the shields indeed blaze like the sun itself, when the glory of the sun god fell upon them. Overhead was raised on silver poles a canopy, supporting a sable curtain or awning, upon which was represented in gold several of the best known constellations of the stars. Thus did Hamilcar, by the symbolical nature of this howdah, which he had had expressly made for this occasion in order to impress the populace, seem to say that, although devoted to Melcareth, the unseen god, of whom no representations could be made, he none the less placed himself under the protection of Baal, the sun god, of Tanith or Astarte, the moon goddess, and of all the other divinities whom the stars represented. He knew that not only would the richness of this new and unheard of triumphal car impress the Carthaginian populace, always impressed by signs of wealth, but that the sacred symbolism of his thus surrounding himself with the emblems of all the mighty gods would impress them still more.

At length, all being ready, Hamilcar, accompanied by his little son, Hannibal, issued from the house, being surrounded by a body of his generals. Then the elephant was ordered to kneel, and a crowd of slaves ran forward with a ladder of polished bronze to place against its side. A body of “hastati,” placed as a guard of honour, saluted by raising high above their heads and then lowering to the ground the points of their polished spears, a movement which they executed with the most absolute precision. Hamilcar looked critically at the soldiers for a minute, to see if there were any fault to detect in their bearing, then, when satisfied that nothing was wrong, acknowledged the salute and turned to compliment the officer in command. He happened to be Xanthippus, a son of him who had defeated Regulus. The troops were a body of 200 Greeks who had fled to Carthage from Lilybæum to escape slavery at the hands of the Romans. This young officer himself had joined Hamilcar in Sicily, and done him good service since.

“ ’Tis well! Xanthippus,” he said, “if thy soldiers are always as worthy of thee as they are on this auspicious day, thou too shalt some day be worthy of thy father.”

It was said so that all the band of Greeks could hear, and said in Greek. The praise was just enough, but not too much. It was a great deal from Hamilcar.

Without stirring an inch from the statuesque bronze-like attitudes in which they stood, a simultaneous cry arose from every throat that rent the air.

“Evoe Hamilcar!” Then there was silence.

Then instantly, on a signal made to him by Hamilcar, Xanthippus gave a short sharp order. Once more the spear points being lifted simultaneously from the ground flashed high in the air, then with a resounding thud all the butt ends of the spears were brought to the ground together, and the troops remained like a wall.

Hamilcar and his little son now mounted the elephant; the generals and staff officers who had accompanied him from the interior of the palace, also mounted the richly caparisoned horses which brilliantly clothed slaves were holding, and placed themselves on each side of the elephant. A blare of trumpets burst forth from musicians stationed behind the Greek spearmen, and the triumphal procession began its march towards the temple of Melcareth.

A trumpet note from a mounted herald now gave the signal to march to the forty elephants and other troops stationed ahead on the Great Place.

Here there was no delay. Hamilcar had given orders that the Vicus Satyrnus, that passing by the temple of Moloch, was the one to be followed, but the road was of course too narrow for a large number of elephants to march abreast. But they were well trained; all the elephants in both lines turned to the right into file, and every second elephant then coming up, the whole body was formed instantly into ten sections of four elephants each. The leading section of elephants now wheeled to the left at a trot, and all the others following at a trot, wheeled at exactly the same spot and the whole marched up the Vicus Satyrnus. Thus the square was clear of their enormous bulk soon enough to allow the Numidian cavalry of Naravas, also moving at a trot, to clear the square in time to avoid checking the advance of the Sacred Band marching behind on foot. When once the whole line, both of elephants and cavalry, was clear of the square, they assumed a walking pace, and then the musical instruments on the elephants were played loudly with triumphant music, which brought all of the inhabitants who, for it was still early, had not yet started for the temple of Baal, to the windows, verandahs, and doors.

“Hamilcar! Is Hamilcar coming?” they cried excitedly to those on the elephants and to the cavalry. But these were far too well trained to pay the slightest attention, and pursued their way in silence.

When Hamilcar arrived, on his elephant, opposite the Forum, he saw the whole of the hundred senators standing on the verandah facing the road that he had to pass. All were dressed in purple togas, their necks were adorned with heavy necklaces of pearls or of sacred blue stones, large ear-rings were in their ears, their fingers were covered with rings, their wrists were ornamented with bracelets, and their sandals blazed with jewels.

Willingly or not, they, with one exception, saluted Hamilcar respectfully as he passed. The exception was a fat, flabby, middle-aged man with face and eyebrows painted. He was overloaded with gems and jewellery, but not all the jewellery in the world could have redeemed the ugliness of his face, or the awkwardness of his figure. As the elephant bearing Hamilcar approached, this man was apparently engaged in a wordy war with the soldiers lining the streets. He was evidently trying to force his way between their ranks, but the foot soldiers, smiling amusedly, placed their long spears lengthwise across the spaces between the horse soldiers who separated them, and kept him back. Gesticulating wildly, and perspiring at every pore, this grandly-dressed individual was cursing the soldiers by every god in the Punic calender, when the great General, the saviour of Carthage, arrived upon the scene. He instantly ordered the herald to sound a halt.

“Salutation to thee, O Suffete Hanno,” he cried. “Why, what ails thee this morning? Art thou perchance suffering from another attack of indigestion, and were not the oysters good last night, or was it the flamingo pasties that have been too much for thee?”

“Curses be upon thy head, Hamilcar, and upon thy soldiers too,” replied the other petulantly. “I but sought to cross the road to join my family in my house yonder, when these foreign devils of thine prevented me—me, Hanno, a Suffete of Carthage! It is atrocious, abominable! I will not stand it. I will be revenged.”

Hamilcar glanced across the road to where, on a balcony within a few yards of him, were standing a bevy of young beauties, all handsomely attired. They were all smiling, indeed almost laughing, at the exhibition of bad temper by the overgrown Suffete; or maybe it was at Hamilcar’s remark about his indigestion, for Hanno was a noted glutton. Seeing the young ladies, the General continued in a bantering tone:

“Ay! indeed, it is a meet cause for revenge that thou hast, O Hanno, in being thus separated, if only for a short space of time, from thy lovely daughters yonder.”

“My daughters, my daughters!” spluttered out Hanno excitedly. “Why, thou knowest I have no daughters, Hamilcar. Dost thou mean to insult me?”

“I insult thee, noble Hanno! Are those noble young beauties, then, not thy daughters? Surely thou must pardon me if I am mistaken, but meseems they are of an appropriate age, and thou saidst but this very minute that my soldiers, meaning, I suppose, the soldiers of the State, had prevented thee from joining thy family yonder. Of what, then, consists thy family?”

At this sally there was a loud laugh, not only among the young girls on the balcony, but from all the assembled senators. For it was a matter of common ridicule that Hanno, whose first wife had been childless, had put her away in her middle age, and taken advantage of the recent law permitting polygamy to take to wife at once half a dozen young women belonging to noble families, whose parents were afraid to oppose such a dangerous and powerful person. Hanno was furious, but strove to turn the tables by ignoring this last remark.

“Whither goest thou, Hamilcar, with all this army? Hast come to conquer Carthage?” he asked sarcastically.

“And how could I conquer Carthage when it contains a Hanno, conqueror apparently of all the hearts therein? Could Lutatius Catulus have conquered Lilybæum even had but the mighty Admiral Hanno remained a little longer in the neighbourhood?”

This reference to Hanno’s defeat at the Ægatian Islands made him furious. He could not bear the smiles he saw upon his young wives’ faces and the sneers he imagined upon the faces of the senators behind him. He broke out violently:

“Whither goest thou, Hamilcar, with all these troops? As thy co-Suffete I demand to know, lest thou prove to be plotting against the State,” and he stamped upon the ground in rage. Hamilcar smiled sarcastically.

“I go, Hanno, where all good Carthaginians should go on a day like this, to offer a sacrifice to the gods.”

“Ah!” cried Hanno, seeing a chance, “ ’tis well that spite of all former evasions thou hast at length determined to do thy duty to thy country by frying yonder brat of thine as a thanksgiving to Moloch. I would that I might be there to see the imp frizzle, and all the rest of the Barcine tribe as well.”

Hamilcar was now angry, but he answered in apparent politeness and good humour:

“There are some bodies that will frizzle far better than such a morsel, Hanno; but since thou wouldst see some frizzling, thou shalt even now accompany me as far as the temple of Baal. I have plenty of room on the elephant.”

“Come hither, Idherbal,” he cried, the chief of the Sacred Band having taken up a position near him, “tell some of thy men to assist the noble Suffete on to the car beside me. He is anxious to see some burning done to-day. He shall not be deprived of the pleasure of assisting in person at the burnt sacrifices.”

Hanno turned pale. He tried to retract his words. The large tears fell down his flabby cheeks. He attempted to resist. But resistance was useless. In a few seconds the soldiers of Idherbal very roughly forced “the soldier’s enemy,” as he was rightly termed, upon the car beside Hamilcar, and the procession again started, leaving the hundred senators and all the women on the balcony, not that these latter cared much, trembling with fear; for they imagined, and with apparent reason, that Hamilcar was about to offer Hanno as a burnt sacrifice to Moloch, and the senators did not know if their own turn might not come next. Therefore, raising their robes in dismay, they all rushed into the Forum, not caring in the least as to what might be the fate of Hanno, but only trembling for their own skins. Might not the time have really come when Hamilcar was about to revenge himself upon all the ancients for their long-continued neglect of him and all the best interests of Carthage? And was not all the power in his hands? Thus they reasoned.

There was no doubt about it that all the power was in the hands of Hamilcar, and that, if he had been only a self-seeking man, he could easily that day and at that hour have seized and burnt not only Hanno, but also all those of the rich and ancients of Carthage, whom he knew to be inimical to himself. He could with the greatest ease have shattered the constitution, denounced the captured senators to the people as equally responsible with the mercenaries for all the miseries they had suffered, and caused them to be offered up wholesale to Baal in that very same holocaust with Matho and Hanno. But Hamilcar was not a self-seeking man, or he would that day, after first removing all his enemies from his path, have declared himself King of Carthage. And the people would have applauded him, and he would have ruled wisely, and probably saved Carthage from the terrible destruction which awaited her later as a reward for treating his son Hannibal, in after years, with the same culpable neglect that she had shown himself.

Hamilcar, however, did not imagine that his duty to his country lay in making himself king. Nevertheless, he determined to show his power, and to establish it over the senators, at least until such time as he should have obtained from them what he wanted—what he considered needful for his country’s welfare merely, and not for his own.

To the young Hannibal, who had from the time of earliest youth been brought up to look upon his father’s foes as his own, every word of what had taken place was full of meaning. Looking disdainfully at the pale-faced Suffete, who, with the tears flowing down his fat cheeks, looked the image of misery, he asked:

“Father, is it true that this man wanted you to offer me up as a sacrifice to Baal? I have heard so before!”

“Yes, it is true, my son, and I should, owing to the pressure put on me, doubtless have done so had I not thought that thou wouldst be of far more use to thy country living than dead.”

“Ah! well,” replied Hannibal complacently, “now we will burn him instead, and he will deserve it, and someone else will get all his young wives. I am glad! But if I were going to be burned I would not have blubbered as he is doing like a woman. Just look at his disgusting tears! I suppose it is all the fat running out. Pah! how soft he is!” and the boy disdainfully dug his finger into the soft cheek of Hanno, just below the eye, where it sunk in the fat nearly up to the knuckle.

“Do not defile thy hands by touching the reptile, Hannibal,” remarked his father.

So the boy desisted, and sat silently and disgustedly watching the wretched man as they moved on.

Meantime, as the procession advanced slowly along the crowded streets, and the people saw the tear-stained and miserable-looking Hanno seated on the grand elephant in the gorgeous shining car beside Hamilcar, whose mortal enemy he had always shown himself to be, the word was passed from mouth to mouth throughout the multitude, “Hamilcar is going to burn Hanno! Hamilcar is going to sacrifice Hanno!” And the fickle people shouted loudly cries of welcome and triumph for Hamilcar, and gave groans and howls of detestation for Hanno. So certain did his end seem to be, that the wretched man was dying a double death beforehand.

At length the open place was reached by the temple of Moloch. Here all the women who had heard the cry became perfectly delirious with delight when they saw the fat Suffete in his miserable condition. “Smite him, smite him,” they cried. “Tear him to pieces; let us drag him limb from limb; the man who has caused the war; the man who has deprived us of our lovers and murdered our husbands, but who has, nevertheless, taken six young wives himself. Burn him! burn him!” And before the guards lining the streets knew what was about to happen, at least a hundred women slipped under their arms, and made a way through. Then rushing to Hamilcar’s elephant, they endeavoured to spring up into the car, with the hope of tearing the hated Suffete to the ground.

Motee was the tallest elephant in Carthage, and they could not effect their purpose, though one young woman, more agile than the rest, being helped by others, got such a hold of the trappings, that she was able at last to swing herself right up into the car.

“This kiss is for my lost lover,” said she, and seizing Hanno by the ears, she made her teeth meet through the flabby part of his cheek; “and this kiss for thy six wives,” she cried, and this time she made her little white teeth meet right through the other cheek just below the eye.

The soldiers overcame the other women and beat them back, and even got hold of Hanno’s assailant by the legs; but for a while she could not be dragged away, for Hanno himself was clinging with both hands to the side of the car, and she had him tight by the ears and with her teeth. At last, exhausted, she let go; but as she did so, she scored his face all down on both sides with her long finger nails, leaving him an awful picture, streaming with blood.

Meanwhile the drums and trumpets had ceased sounding, and the cries of the miserable, tortured victims inside the temple could be plainly heard as the priests ran out to see what was going on. The smell of roasting flesh also filled the air with a sickening odour.

The women who had been beaten back from the elephant now remained outside the line of soldiers, which had been reinforced by some of Hamilcar’s escort. They could not possibly approach a second time; but, like a group of hungry hyenas, they remained screaming and gesticulating, thirsting for their prey. Many of them were beautiful, most of them were young. Their raven tresses were raised above their heads, and bound with fillets of gold. Their dresses displayed their beautiful arms and bosoms, their necks were covered with jewels, their wrists with bracelets, and their fingers were almost concealed by the rings of precious stones. They were clothed in purple and fine linen; but in spite of all these signs of womanhood gently nurtured, they had already ceased to be women, and had become brutes. The burning, the blood, the torture, the smell of the roasting flesh, the cries of the victims, the sight of the dying agonies of men from an early hour that morning, had completely removed all semblance from them of the softer attributes of womanhood, and they had become panthers, wolves.

“Give him to us, Hamilcar!” they screamed; “give over to us the wretch, who, by refusing to pay the mercenaries, caused the war. We will burn him, torture him! Burn him! burn him!” They became fatigued at length with their own screaming, until many fell upon the ground fainting and exhausted. Then Hamilcar sent for all the musicians upon the elephants in front. He also commanded the priests to bring all the kettle drums forth from the temple of Baal, whose terrible brazen figure could be plainly seen, red-hot and glowing, through the smoke. Three separate times he commanded all the brazen instruments and the drums to be sounded together. The horrible din thus raised drowned the cries of the women; but no sooner did the blare of the trumpets cease, and the roulade of the drums fall, than the women began shrieking once more, “Give him to us, Hamilcar! Let us tear him in pieces, torture him! Burn him! burn him!”

Then to enforce silence, Hamilcar, in addition to the awful sounds of the musical instruments, ordered the drivers of the elephants to strike them with the goads and make them trumpet. The trumpeting of the elephants, in addition to the rest of the infernal din, at length completely drowned the yells of the women. They subsided in complete silence. Then, rising in his car, Hamilcar addressed the multitude:

“Oh, priests! men and women of Carthage! it is not meet that I decide upon this man’s fate. He hath been mine enemy all my life as much, ay, far more, than he hath been yours. His fate, whether we shall slay him now or leave him to the future terrible vengeance of the gods, shall not be left in either your hands or in mine. Here in this car with him and me, a sacred car devoted as all can see to all the gods, is my son Hannibal, the favoured of Baal. His young life, from jealousy of me the father, this miscreant, Hanno, hath often tried to take; ay, even this very day before the Hundred Judges he suggested openly that I—I who have saved you all, and saved Carthage, should sacrifice my young son in a common heap with the bloodthirsty malefactors who are, rightly for their awful crimes, being sacrificed this day to the mighty Baal Hammon.”

Here such a howl of execration against Hanno again burst forth from the crowd that the elephants had once more to be made to trumpet, and the musical instruments to raise their hideous din, to obtain silence.

Then Hamilcar continued:

“In the hands of this my son, whom I hope may be spared to protect this country even as I have done, I leave the life of his would-be murderer. Speak, Hannibal, my son, say, shall this Hanno, who would have slain thee, die now for thy vengeance and for mine? Or shall he be left in the hands of the gods, who doubtless for our punishment have placed such a scourge here on earth among us?”

The boy Hannibal arose and regarded steadily, first the now silent crowd, and then the bloated form of Hanno, who, with face all bleeding, hung back upon his seat in the car, while stretching forth his ring-covered hands to the child as if for mercy. Then he spoke clearly, in the voice of a child but with the decision of a man:

“My father, and people of Carthage, I am destined from my birth to be a warrior, one to fight for and protect my country. Do not then let my first act, where the life of others be concerned, be that of an executioner. It would not be worthy of one of the blood of Barca. Let Hanno live. The gods are powerful; his punishment lies in their hands!”

The boy sank back upon the cushions in the car, and a roar of applause greeted the speech, for it met the fancy of the crowd. Henceforth the life of Hanno was secure. He was taken off the elephant, placed in a litter, and sent to his home under a small escort. But the escort was not necessary. He was now looked upon as one under the curse of the gods, and no one in the crowd, whether man or woman, would have defiled their hands by touching him.

Meanwhile, Hamilcar and his son proceeded to the temple of Melcareth, where, entering the sacred fane quite alone save for the priests, the former sacrificed to his protecting deity a bull and a lamb. For no human blood was ever shed in those days in the temple of the Carthaginian unknown god. And in that solemn presence, on that sacred occasion, the boy Hannibal plunged his right arm up to the elbow in the reeking blood of the sacrifice, and solemnly vowed before the great god Melcareth an eternal hatred to Rome and the Romans.

* * * * * * * *

A few weeks later, Hamilcar, having won from the terror-stricken senators all that he required—supreme and absolute command, and sufficient money and war material—left Carthage with an army and a fleet. He coasted ever westward, the army marching by land, and subduing any malcontents that might still exist among the Numidians and Libyans. At length, having reached the Pillars of Hercules, the modern Straits of Gibraltar, he, by means of his fleet, crossed over into Spain. And Hannibal accompanied his father.

END OF PART I.

All the lower parts of Spain had been conquered and settled. Hamilcar had died, as he had lived, fighting nobly, after enjoying almost regal rank in his new country. Hasdrubal, who had succeeded him, was also dead, and now Hannibal, Hamilcar’s son, a man in the young prime of life, held undisputed sway throughout the length and breadth of the many countries of Iberia that his father’s arms and his father’s talents had won for Carthage.

In the delightful garden of a stately building reared upon a hill within the walls of the city of Carthagena or New Carthage, a group of girls and young matrons were assembled under a spreading tree, just beyond whose shade was situated a marble fish pond, filled with graceful gold and silver fishes. The borders of the pond were fringed with marble slabs, and white marble steps led down into the basin for bathing purposes. In the centre a fountain threw up in glittering spray a jet of water which fell back with a tinkling sound into the basin.

Upon the marble steps, apart from the other young women, sat a maiden listlessly dabbling her fingers and one foot in the water, and watching the fishes as they darted hither and thither after some insect, or rose occasionally to the surface to nibble at a piece of bread which she threw them from time to time. The girl, who was in her seventeenth year, was in all the height of that youthful beauty which has not yet quite developed into the fuller charms of womanhood, and yet is so alluring with all the possibilities of what it may become.

Of Carthaginian origin on the father’s side, her mother was a princess of Spain—Camilla, daughter of the King of Gades. She had inherited from the East the glorious reddish black hair and dark liquid eyes, and had derived from the Atlantic breezes, which had for centuries swept her Iberian home, the brilliant peach-like colouring with its delicate bloom, seeming as though it would perish at a touch, which is still to be seen in the maidens of the modern Seville. For this city of Andalusia had been, under the name of Shefelah, a part of her grandfather’s dominions. Tall she was and graceful; her bosom, which was exposed in the Greek fashion on one side, might have formed the model to a Phidias for the young Psyche; her ivory arms were gently rounded and graceful. Her rosy delicate foot was of classical symmetry, and the limb above, displayed while dabbling in the water, was so shapely, with its small ankle and rounded curves, that, as she sat on the marble there by the fish pond in her white flowing robes, an onlooker might well have been pardoned had he imagined that he was looking upon a nymph, a naiad just sprung from the waters, rather than upon the daughter of man.

But it was in the face that lay the particular charm. Above the snow-white forehead and the pink, shell-like ear, which it partially concealed, lay the masses of ruddy black hair bound with a silver fillet. The delicious eyes, melting and tender, beamed with such hopes of love and passion that had the observer been, as indeed were possible, content for ever to linger in their dusky depths of glowing fire, he might have exclaimed, “a woman of passion, one made for love only, nothing more!” Yet closer observation disclosed that above those eyes curved two ebony bows which rivalled Cupid’s arc in shape, and which, although most captivating, nevertheless expressed resolution. The chin, although softly rounded, was also firm; the nose and delicious mouth, both almost straight, betokened a character not easily to be subdued, although the redness and slight fulness of the lips seemed almost to proclaim a soft sensuous side to the nature, as though they were made rather for the kisses of love than to issue commands to those beneath her in rank and station.

Such, then, is the portrait of Elissa, Hannibal’s daughter.

The other ladies, including her aunt, the Princess Cœcilia, widow of Hasdrubal, a buxom, merry-looking woman of thirty, kept aloof, respecting her reverie. For, notwithstanding her youth, the lady Elissa was paramount, not only in the palace, but also in the New Town or City of Carthagena during the absence of her father Hannibal and her uncles Hasdrubal and Mago at the siege of the Greek city of Saguntum, and had been invested by Hannibal, on his departure, with all the powers of a regent. For, being motherless almost from her birth, Hannibal, a young man himself, had been accustomed to treat her as a sister, almost as much as a daughter. He had been married when a mere lad, for political reasons, by his father Hamilcar, and Elissa had been the sole offspring of the marriage. Since her mother’s death he had remained single, and devoted all his fatherly and brotherly love to training his only daughter to have those same noble aims, worthy of the lion’s brood of Hamilcar, which inspired all his own actions in life. And these aims may be summed up in a few words: devotion to country before everything; self abnegation, ay, self sacrifice in every way, for the country’s welfare; ambition in its highest sense, not for the sake of personal aggrandisement, but for the glory of Carthage alone. No hardships, no personal abasement even—further, not even extreme personal shame, or humiliation if needful, was to be shrunk from if thereby the interests of Carthage could be advanced. Self was absolutely and at all times to be entirely set upon one side and placed out of the question, as though no such thing as self existed; the might, glory, and power of the Carthaginian kingdom were to be the sole rule, the sole object of existence, and with them the undying hatred of and longing for revenge upon Rome and the Romans, as the greatest enemies of that kingdom, through whom so many humiliations, including the loss in war of Sicily, and the loss by fraud of Sardinia, had been inflicted upon the great nation founded by Dido, sister of Pygmalion, King of Tyre.

These, then, were the precepts that Hannibal had ever, from her earliest youth, inculcated in his daughter; and with the object that she might learn early in life to witness and expect sudden reverses of fortune, he had hitherto, since her twelfth year, ever taken her with him upon his campaigns against the Iberian tribes. Thus she might from early experience be prepared, should the cause arise, to fulfil a noble destiny, even as he himself, having from his tenth year borne arms under his father Hamilcar and brother-in-law Hasdrubal, had been prepared for the mighty role which, with the siege of Saguntum, he was now commencing to fill in the world’s history.

For the Greek city of Saguntum, on the eastern coast of Spain, was strictly allied with Rome, and the fact of Hannibal’s attacking it was, he well knew, equivalent to a commencement of a new war with mighty Rome herself.

Upon Hannibal’s departure for the siege of Saguntum some eight months previous, he had taken all the generals and captains in whom he could put trust and the greater part of the army with him. Although not styled a king, his power was at that time more than regal in all the parts of Spain south of the Ebro, and his authority as regards the care of the City of New Carthage itself he had, on his departure, delegated under his sign manual and seal absolutely to his daughter Elissa.

It is, then, no cause for wonder, if her female companions looked with some degree of awe and respect upon this sixteen-years-old girl who sat there so pensively dabbling her hands and feet in the marble basin, while raising her head occasionally to cast a glance through the embrasures on the battlemented walls surrounding the garden, upon the gulf below and the blue sea stretching out far beyond. Elissa had far sight, and it seemed to her once or twice as though she could make out, shining in the evening sun, far away upon the horizon, the white sails of ships. But they were no larger than specks, and soon disappeared altogether; therefore the maiden, thinking that she had been misled by some sea birds, soon gave up watching the sea, and returned to the apparent contemplation of the fishes, but really to the continuation of the reverie upon which she was engaged.

Meanwhile the ladies under the trees were chatting away merrily.

“Oh! dear me, how hot it is,” exclaimed the rotund little Princess Cœcilia, fanning herself vigorously with a palm leaf fan. “I am sure when my poor husband, Hasdrubal, built this city of New Carthage, he must have selected it purposely as being the warmest site in all Spain, just to remind him of his native country which he was so fond of. Or else,” she continued, “it was to try and keep down my inclination to fat. Oh! dear me!” and she fanned away at herself more vigorously than ever.

“Don’t call it fat,” interposed Cleandra, a very handsome fair young woman of about twenty, who was herself by no means inclined to be thin—“say rather adipose deposit, it is a far more elegant way of putting it.”

“Or plumpness, Cleandra, that is nicer still,” struck in Melania, a dark young beauty with vivacious black eyes, who was a year younger. “I wish I could call myself plump like thee, I am sure I should not mind the heat,” she added, “instead of being the scarecrow that I am,” and rising she surveyed with mock ruefulness her really very graceful figure. She was the tallest of all the young women there, and was perfectly well aware of the fact that her comparative slenderness was most becoming to her willowy and lissome figure.

“A scarecrow, thou a scarecrow,” almost screamed the little Cœcilia. “Oh! just listen to the conceited thing; why, thou hast a lovely figure and thou knowest it; there is none in all New Carthage, save Elissa yonder, who can compare to thee. But then, of course, no one can compare with her in any way. But what a girl she is! how can she sit out there in the afternoon sun like that? the worst kind of sun, my dears, for the complexion, I can assure you. I am sure if I were to remain like that for only five minutes I should lose my complexion entirely, yes, become perfectly covered with freckles I am certain, in even less than five minutes. Now what are you giggling at, you naughty girls? I declare you are too wicked, both of you; I shall have to report you to our Queen Regent yonder and ask her to put you both in the dungeon if you make fun of an old lady like me. Alas! thirty years of age, don’t you call that old?”

For with a sly glance at each other the two girls had mutually looked at the lively little princess’s manifestly artificial complexion which was trickling away in little runnels down her cheeks.

“I wonder what she is thinking about?” she interposed hastily, to turn away the merry girls’ attention from herself, and glancing across towards the lady Elissa.

“Who?” said Cleandra.

“Why, Elissa, of course,” replied that lady’s aunt. “Canst thou not see that she hath been in a brown study for ever so long? She is no more thinking of the fish than I am; her thoughts are miles and miles away. But just notice how pretty the ruddy tints are in her dark hair, lighted up like that by the afternoon sun.”

“Perhaps she is thinking of affairs of State,” answered Cleandra, “and whether she is to put us in that black hole or no.”

“Or, perhaps,” said Melania with a grain of malice, “and far more likely, she is thinking of the siege of Saguntum and whether a certain young officer of cavalry called Maharbal will ever come back from the war again to do what we girls cannot hope to do, that is cheer her in her solitude. I really should like to go and disturb her, she reminds me so of her namesake Dido—Elissa is Hebrew for Dido, thou knowest, Lady Cœcilia—mourning on the heights of Carthage for her lost Æneas.”

“I wonder what she sees in that Maharbal,” continued Melania, in a tone of pique; “a great big mountain of a hobbledehoy, that’s what I call him, and merely a prefect of the Numidian cavalry, too. Such assurance on his part to be always making love to her! I wonder that Hannibal allows it—a mere nobody!”

“A mere nobody! a hobbledehoy! nonsense!” said the princess, “thou’rt jealous, Melania, because he never looks at thee. Why, he is own nephew to Syphax, King of Massaesyllia, and cousin to the powerful Massinissa, King of Massyllia, both great Libyan princes.”

“Mere vassals of Carthage! and the last named not very trustworthy,” replied the other interrupting.

“Well then,” gabbled on the princess, “look at his strength, a hobbledehoy indeed; Maharbal is a regular Hercules, and hath a beautiful face just like the celebrated Hermes of Praxiteles. I think Elissa will be a very lucky girl if she weds a magnificent fellow like that; she will be the mother of a race of giants.”

“Shsh! Shsh!” cried both the girls, smiling in spite of themselves. “Elissa is listening to all we are saying—just look at her.”

“Yes, yes, you wicked people, and she hath been listening for the last quarter of an hour,” cried Elissa, springing to her feet as red as a rose. “But really, my aunt is too bad, she maketh me ashamed; say, what shall we do with her for punishment? put her in the fish pond I think.” Bounding across the open space, she playfully seized upon the merry little woman, and aided by the two others, dragged her in spite of her cries, screams, and vigorous resistance to the very brink of the marble basin. She struggled violently, and but with difficulty escaped her fate.

“Oh, dear me! think of my complexion—cold water in the afternoon is bad for it. Oh! I did not mean a word, dear Elissa. Oh, dear me, I shall die,” and with a vigorous final effort for freedom, as she was really a very strong young woman, suddenly she pushed both Elissa and Melania together over the brink so that they fell with a splash into the shallow pond. Then being left alone with the plump Cleandra, who had no strength whatever, she speedily overcame her, and threw her in after the others, remaining with torn garments and dishevelled hair, shrieking with laughter, and panting for breath on the bank.

“Now there is naught for us but to have a bathe,” cried Elissa gaily; and first drenching the princess with a shower of spray, and then springing up the marble steps, the three girls quickly threw off their thin, wet, clinging garments.

Standing there together in a pretty group for a brief minute or two, poised on the top of the marble steps, with arms raised in graceful curves while loosening the fillets of silver from the hair that fell in masses to the hips, they seemed in all their youthful beauty like the three graces personified.

At that very moment, from behind the trees, the sound was heard of a horse’s hoofs galloping on the turf, and in a second an armed warrior, mounted on a black charger covered with foam and utterly exhausted, appeared upon the scene. At the same time, a great sound of shouting was heard in the town without the garden walls, which shouting was taken up again and again, till the clamour seemed literally to fill the air. The shouting sounded like the cheers for victory.

The princess was the first to recover her composure.

“Why, it’s Maharbal,” she cried; “jump into the water, girls, instantly. Fancy his coming like that!” Then, rushing in front of the warrior, she wildly waved her hands at the horse, shouting, “Go back! Maharbal, go away, thou wicked man, go back. Dost not see that the girls are bathing?”

At that moment they all plunged into the water once more like frightened swans.

“In the name of Hannibal!” cried the young warrior, “let me pass. I must speak to Elissa, and instantly, or my head will fall,” and he held up Hannibal’s signet ring before the dripping princess’s astonished gaze.

“Oh!” screamed the princess, falling back affrighted. “Hannibal’s ring! Yes, of course, Hannibal’s orders are law.”

Maharbal advanced to the edge of the shallow pond. In this the maidens were now crouching and partially concealing themselves under some flags, but in spite of all, their heads and shoulders remained uncovered. Elissa and Cleandra faced Maharbal and strived to look dignified. Melania, on the other hand, had turned her back upon him.

Curiosity and anger combined caused her to turn her head, and she was the first to speak, as Maharbal, his charger beside him, stood upon the steps. Both she and Cleandra, of noble Iberian families by birth, were, although treated as of the family, but slave girls in Hannibal’s household, therefore she had no right to speak in the tone she now used, except the right of outraged modesty that every woman possesses.

“Begone! Maharbal, thou insolent wretch, begone instantly, or the Lady Elissa will have thee scourged and beheaded for thine impertinence. How darst thou insult us, thou ruffian? I wish that thou wert dead.”

At this instant, Maharbal’s war-horse, with a mournful kind of half scream, half sigh, fell upon the ground at the edge of the pond, and with a quiver of all its limbs expired. The warrior turned to watch it for a second, then looking back, remarked sadly: “My best charger, and alas! the third I have killed since yesterday morning. But there is no time for talk. Lady Elissa, my business is with thee alone, and it brooks absolutely not a moment’s delay. Wilt thou kindly direct thy slaves,” and he looked hard at Melania, “to leave the water at once. I must speak with thee alone. I obey the General’s strict orders.

“Pray be quick,” he added, “for I feel my strength rapidly failing me, and if I have not fulfilled my duty before, like my horse yonder, I die, I shall have failed in my vows to my General and to my country.”

He removed his helmet as he spoke, and all the three maidens noticed not only that the young man was turning deadly pale, but that a wound on the side of the head, which had been covered with coagulated blood, had broken out, and was bleeding violently afresh.

But he had yet strength to hand a garment, the first he found to hand, to Elissa, who, while attiring herself in the water, turned sharply to her attendants, and addressed them authoritatively.

“Leave the water, maidens, and let no false shame delay ye for a moment, for I see this is a matter of life or death. Begone at once, and thou, mine aunt,” she cried.

Like startled deer, the two girls, having recovered some of the scattered raiment, fled from the pond, and rushed within the palace, followed by the dishevelled Princess Cœcilia. But whether from being reminded thus forcibly that she was but a slave, or from a combination of feelings, no sooner had Melania reached her apartment than she burst into a flood of violent weeping. The princess was wringing her hands as she went, and talking aloud.

“Oh, dear me! this is very odd and very dreadful, and most improper! But poor Maharbal’s horse is dead, and he looks at death’s door himself. Oh! what hath happened? I hope Hannibal is not dead as well, or a prisoner, or anything awful. But nay! he hath sent his seal. But I must prepare a room for poor Maharbal to die in; where shall I get a bed big enough? what a long body he will be.” And so chattering to herself, for want of anyone else to talk to, she left Maharbal, the handsome young warrior, alone with the beautiful child of sixteen, the Lady Elissa.