Title: With Boone on the frontier

Subtitle: Or, The pioneer boys of old Kentucky

Author: Ralph Bonehill

Release Date: September 14, 2023 [eBook #71642]

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

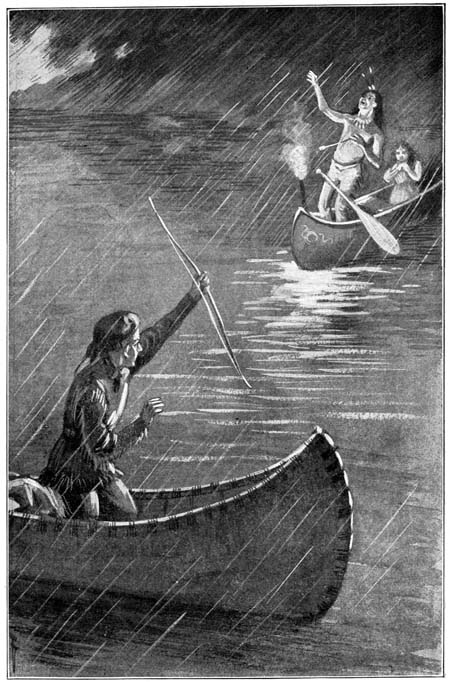

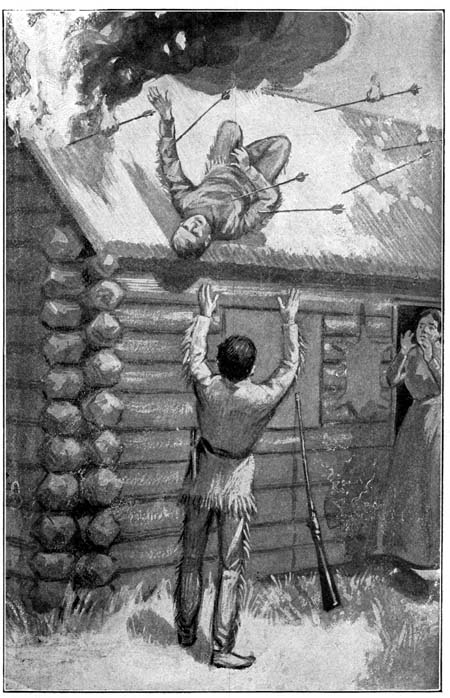

“LONG KNIFE WAS TAKEN FAIRLY AND SQUARELY IN THE BREAST.”—P. 63.

OR

THE PIONEER BOYS OF OLD

KENTUCKY

BY

CAPTAIN RALPH BONEHILL

AUTHOR OF “THE BOYS OF THE FORT,” “WITH CUSTER IN

THE BLACK HILLS,” “WHEN SANTIAGO FELL,”

“THE YOUNG BANDMASTER,” ETC.

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1903

BY

THE MERSHON COMPANY

“With Boone on the Frontier” relates the adventures of two youths who, with their families, go westward into what was at that time the wilderness of Kentucky, to join Daniel Boone in settling what has since become one of the richest and most prosperous of our States.

The history of this movement, and the history of the man who was its greatest leader, are as fascinating as the most exciting novel ever written. Daniel Boone was a character almost unique in American history, a man the very embodiment of pluck and energy, and one who knew neither fear nor the meaning of the word fail. For years he had his eye on the great green fields of Kentucky, and he resolved, in spite of the dangers from natural causes and from the Indians, to open up this territory to the hundreds of pioneers who had become tired of life along the eastern seacoast or close to it, and who wanted to go where they would be less under the rule of those English who were making themselves offensive at that time. While those in the East were fighting the War for Independence he and his[iv] trusty followers were working equally hard to give to this nation a stretch of land of which any people might well be proud.

The first settlement in Kentucky was at Boonesborough, about eighteen miles to the southeast of Lexington, on the Kentucky River. To-day this village is of small importance, but at that time, in 1775, it boasted of a fort which, built under the directions of Daniel Boone, was a rallying point for all the settlers of that territory and a place to which they fled for safety at the first sign of an Indian uprising. It is in and around this fort that many incidents of the present tale occur.

It may be that some, in reading this story, will deem many of the statements made therein overdrawn. Such is far from being the fact. The days in which Daniel Boone lived were full of dire peril to those who lived on the frontier, or who attempted to push further westward over the hunting grounds of the jealous red men, and many were the outrages committed by the Indians, not alone on the men and boys among the pioneers, but also among the women and girls, and even the little children. Let us all be thankful that such days are now past never to return.

Captain Ralph Bonehill.

July 1, 1903.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Two Boys of the Wilderness, | 1 |

| II. | Pursued by the Indians, | 11 |

| III. | A Dismaying Discovery, | 20 |

| IV. | Lost Underground, | 30 |

| V. | The Escape of the Captives, | 40 |

| VI. | Harry and the Bear, | 50 |

| VII. | What Happened in the Rain, | 60 |

| VIII. | Days of Peril, | 70 |

| IX. | Daniel Boone, the Pioneer, | 80 |

| X. | Boone Leads the Way, | 90 |

| XI. | With No Time to Spare, | 100 |

| XII. | Settling Down at Boonesborough, | 110 |

| XIII. | Perils of the Young Hunters, | 120 |

| XIV. | On the Trail of a Thief, | 130 |

| XV. | Fighting the Flames, | 140 |

| XVI. | The Fall of a Hickory Tree, | 150 |

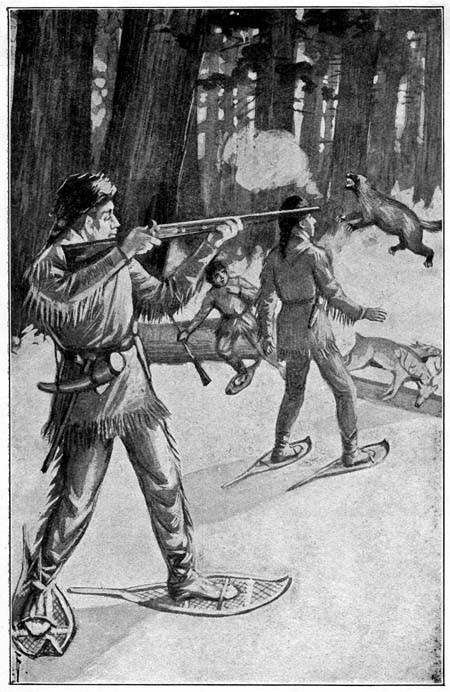

| XVII. | An Adventure on Snowshoes, | 166 |

| XVIII. | Night with the Wolves, | 176 |

| XIX. | The Hunters Hunted, | 185 |

| XX. | Daniel Boone’s Great Shot, | 195 |

| XXI. | The Foot Race at the Fort, | 205 |

| XXII. | Who Was the Winner? | 222 |

| XXIII. | The Rescue of Jemima Boone, | 231[vi] |

| XXIV. | A Night Raid by the Indians, | 240 |

| XXV. | In a Forest Fire, | 250 |

| XXVI. | The Attack on the Fort, | 266 |

| XXVII. | Shot on the Roof, | 276 |

| XXVIII. | The Retreat of the Indians, | 292 |

| XXIX. | The Long-Lost at Last, | 302 |

| XXX. | Back to the Cabin—Conclusion, | 312 |

WITH BOONE ON THE

FRONTIER

“Hark, Joe, what was that?”

“It sounded like the report of a gun, Harry. But I didn’t imagine that anybody was within gunshot of this place outside of ourselves.”

“That was what I was thinking. Do you imagine any of those Indians we met yesterday had guns?” went on Harry Parsons thoughtfully.

“I didn’t see any,” answered Joe Winship. “And if they had ’em I think we would have seen ’em,” he added, as he took up his gun from where it was resting against a tree and looked at the priming.

“We didn’t come out here to have trouble,” continued Harry Parsons. “We only came to see if we couldn’t bag a fine deer or two. If those Indians followed our party——”

The youth came to a stop, for at that instant[2] another gunshot rang out, somewhat closer than the first which had attracted their attention. Then came a rush through the forest and a few seconds later four beautiful deer burst into view.

“Deer!” cried Joe Winship, and leveled his gun at the nearest of the game.

“Don’t shoot, Joe!” cried his companion.

“Why not?”

“If the Indians are after ’em we may have trouble.”

There was no time to argue the matter, for even as Harry Parsons spoke the deer leaped the small brook which wound its way through the mighty forest and in a twinkling were out of sight again. Then all became as quiet as before.

“Don’t hear any Indians,” was Joe Winship’s comment, after straining his ears for a full minute. “And lost a tremendously good shot,” he added regretfully.

“Well, it’s best to be on the safe side. If half a dozen redskins were after those deer we wouldn’t stand any show at all against ’em,” said Harry Parsons, with a decided shake of his curly-haired head. “You remember what our folks told us—to keep out of trouble.”

“But what beautiful deer they were!”

“You are right. And it isn’t likely they’ll come back this way——”

[3]“Hush!”

As Joe Winship uttered the word he caught his companion by the sleeve and pointed through the forest to where there was an opening, perhaps an acre in extent, dotted here and there with small brushwood.

“What did you see, Joe?”

“A couple of Indians. There they are again—getting ready to cross the brook!”

“They came up quietly enough. What shall we do?”

“Let us get behind yonder bushes. They are on the trail of the game, and I don’t think they’ll come this way. But if they do we’ll have trouble just as sure as you are born,” concluded Joe Winship, and led the way to the shelter he had mentioned, quickly followed by his companion.

Joe Winship was a youth of fifteen, tall and as strong as outdoor life can make a boy of that age. He was the only son of Ezra Winship, a hardy hunter and pioneer, one of the number who did so much to build up our country in years gone by. Besides Joe, the family consisted of the boy’s mother and his two sisters, named respectively Cora and Harmony, both of whom were younger than himself.

Harry Parsons was a few months older than[4] Joe. He too was an only son, and had one sister, Clara, two years older than himself. His father, Peter, had in years gone by been a cattle dealer doing business in and around Philadelphia, and had there married his wife, Polly, of Quaker stock.

It was during a visit to Williamsburgh that Mr. Peter Parsons had fallen in with Ezra Winship, about four years previous to the opening of this story. A chance acquaintanceship had ripened into true friendship, which speedily spread from all the members of one family to all the members of the other.

From Williamsburgh the Winships and the Parsons migrated to a small settlement in North Carolina known by the name of Jackson’s Ford. Here log cabins were built and some planting was done by the boys and the others, while Mr. Winship and Mr. Parsons spent a good deal of their time in bringing down game in the almost trackless forests to the west of the rude settlement—the game being used to supply the table with meat and the pelts being sold or traded for household commodities at a trading-post thirty-five miles away.

In those days—just previous to the Revolution of 1776—the great West was an unknown country to the American colonists. There were settlements[5] in plenty along the Atlantic seacoasts, and for several hundreds of miles inland, but beyond this was, to them, the trackless forests and the unknown mountains, inhabited by game of all sorts and Indians.

One of the leading pioneers of those times, and one who will figure quite largely in our story, was Daniel Boone. Boone had already gone into the wilderness beyond the Kentucky River, and had come back to tell of the richness of the land there and the abundance of game. As a result a company was formed to settle the territory now known as the State of Kentucky, and among the first of the pioneers to take part in this move westward was Peter Parsons, who helped to erect a fort at what was afterwards called Boonesborough.

The settlement at Boonesborough was quickly followed by other settlements at Harrodsburgh, Boiling Spring, and St. Asaph, and when it became an assured fact that Kentucky was to be settled and held by the bold pioneers who had followed in the footsteps of Daniel Boone, Peter Parsons sent back word to Jackson’s Ford asking Ezra Winship to join him in this “far western country,” and bring all the members of the two families with him. He stated that he had selected two fine grants of land upon which they[6] could build, and that upon his arrival Mr. Winship should have his pick of the two prospective farms.

In those days to move, especially with one’s household effects, was no easy matter, and it was a good two months before all was in readiness for the start. The Winship and the Parsons family did not go alone, but were accompanied by four other pioneers and their families and a pack train of fourteen horses, for to get anything like a wagon or cart through the wilderness was utterly impossible.

To the boys the move westward seemed to promise no end of sport, and they willingly did all they could to further the project. But the girls and their mothers dreaded to think of this step into the great wilderness, and Mrs. Parsons shook her head doubtfully as she said in her quaint Quaker way:

“Friend Ezra, since Peter wishes me to come to him, I will go with thee. But I am of a mind that our journey will be a troublous one, and that the Indians will not be as friendly as thee imagines.”

“Have no fear, Mistress Parsons, but that we will get through in safety,” answered Ezra Winship. “The trail has now been used half a score of times, so we cannot very well get lost, and as[7] for the Indians, if we do not harm them I doubt if they harm us.”

But even though he spoke thus, Ezra Winship knew that all who were to move westward with him were sure to encounter more or less of peril. Wild animals roamed the forest, and the Indians, although apparently friendly, were not to be trusted. To this were to be added the perils of storms and of forest fires, and the dangers of crossing rapidly flowing streams in such frail craft as they could build, or upon horseback.

All told, there were five men and six boys in the train that started out from Jackson’s Ford one warm and pleasant day. Before the exodus began Ezra Winship called the men and the older boys aside and gave them a little advice.

“We are moving into a strange territory,” he said. “There is no telling what perils we may have to face. You have made me your leader, and that being so, I feel it my duty to warn each one to be on his guard constantly. In traveling, always be sure to keep the rest of our train in sight, and never discharge your weapons without reloading immediately. If any Indians appear, treat them well so long as they are friendly, but do not trust them too far.”

The progress westward was slow, but twelve miles being covered the first day, fifteen the[8] second, and ten the third. The trail—a narrow path used occasionally by the buffalo and by the Indians—was an exceedingly rough one, winding in and out of the forest and along the banks of rivers and small streams. At certain spots were huge rocks, over which buffalo and Indians could scramble with ease, but around which the pack horses had to make their way slowly and cautiously.

The party were out a week before any Indians appeared. Then one of the pioneers announced that he had discovered three red men looking down upon them from a nearby cliff.

“They disappeared the minute I spotted ’em,” said the pioneer, whose name was Pepperill Frost, generally shortened to Pep Frost.

“We must be on our guard against them,” said Ezra Winship, and that night a strict guard was kept, but no red men appeared.

But the next afternoon, about three o’clock, four Indians showed themselves at a spot where the trail crossed a shallow, rocky brook. They came up with their hands before them and with their bows and arrows and other weapons slung over their backs.

“To what place journey our white brothers?” questioned one of the Indians, after the usual greeting in his native tongue.

[9]“To some place where they can live in peace with our red brethren,” answered Ezra Winship cautiously.

After this the Indians said little, but begged for some tobacco and some Indian meal, a small quantity of which was given to them. They then departed into the forest, disappearing as rapidly as they had come.

“I think we’ll see more of those Indians,” said Pep Frost.

“I believe you,” answered Ezra Winship. “And perhaps they’ll not be so friendly another time. But do not alarm the women folks, for it will do no good.”

Early the following morning an accident happened which came close to proving fatal to one of the boys, Chet Rockley by name. He was driving a pack horse loaded with provisions along the river bank when the horse slipped and fell into the stream, carrying the lad with him. In the struggle that followed the boy was kicked in the head by the animal. Chet Rockley was rescued by Ezra Winship, but the horse was carried away by the swift current and drowned, and the provisions were lost.

It was decided to rest for two days, to care for young Rockley, and to bring in some game to take the place of the provisions which had been[10] lost. A temporary camp was established at the fork of two small streams, and as soon as this was done the men folks and the boys took turns in going out hunting and fishing.

Joe and Harry had been cautioned not to go too far, and to keep a close watch for Indians. But their anxiety to bring in at least one good-sized deer had caused them to roam further from the camp than at first anticipated. They had seen no game until the four deer burst into view, closely followed by the two Indians already mentioned.

“Do you really think the Indians would prove unfriendly?” questioned Harry, as both boys crouched down behind a thick clump of bushes.

“I do—if they belong to the crowd who called upon us yesterday. There was one Indian in particular, a tall chap, who looked bloodthirsty enough for anything,” said Joe.

“You mean the fellow called Long Knife?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t deny he did look ugly, Joe. But then a redskin can’t help his looks.”

Here the talk came to a sudden end, for a splashing in the brook reached their ears, telling that the two Indians were not far away. They had not gone after the deer as the boys had imagined, but were coming closer. Harry clutched Joe’s arm, and both youths crouched lower than ever in the grass and brushwood.

In a minute more the two red men were less than a rod away, and the boys could hear them talking softly to one another. Peeping through[12] the bushes, Joe made out the savage face of Long Knife, and saw that the Indian carried a musket of ancient pattern, and a horn of powder and ball, as well as his bow and arrows, and his tomahawk. The second Indian was similarly armed.

Hardly daring to breathe, the boys remained behind the bushes until the Indians had passed the spot and followed the course of the stream a distance of several rods further. Then Harry touched Joe on the arm.

“Did you see it?” he asked, in a low voice, but one full of suppressed excitement.

“See what, Harry?”

“The scalp Long Knife carried. I’m sure it was a fresh one, too!”

“A fresh scalp! Oh, Harry, are you sure?”

“Yes, and the best thing we can do is to get back to the train without delay.”

“But the Indians have gone up the brook——”

“We’ll have to take to the forest and trust to luck.”

“Supposing they have attacked the train? That scalp may be that of one of our party!”

“Let us trust not,” answered Harry, but with a face that showed his anxiety.

The youths had been following the course of the brook, which was lined on one bank with a series of large flat rocks. On these rocks their[13] trail had been lost, so that the Indians had not discovered their footprints in the semi-gloom caused by the heavy forest growth overhead.

“But they’ll find some footprints before long,” said Joe, in speaking of this. “And when they do they may be after us hot-footed.”

Fortunately for the boys the brook, as they remembered, made a long semicircle, so that if they could make their way through the forest in anything of a straight line they would cut off a goodly portion of the distance to camp.

The gun of each was loaded and freshly primed, and each held his weapon ready for instant use should occasion require. Joe led the way, but Harry followed closely in his footsteps.

Less than a hundred yards had been covered when there came a shot from a distance, followed by several others.

“Where can they come from?” questioned Joe.

“I don’t believe we are in sound of the camp, Joe. But if we are, perhaps those other shots came from there, too.”

“No, they were off in that direction.” Joe pointed with his hand. “I can tell you what, I don’t like the looks of the situation, do you?”

“No, I don’t—and that is why I think we had best get back to camp with all speed.”

On and on they went, deeper and deeper into[14] the forest. The summer day was drawing to a close and they knew that in another hour the darkness of night would be upon them.

Suddenly a small wild animal darted up in their path. This caused Joe to fall back upon Harry, and by accident the latter’s gun was discharged, the buckshot whistling past Joe’s left ear and tearing through the boughs overhead.

“Oh, Joe, are you shot?” cried Harry in keen alarm.

“I—I reckon not,” stammered his companion, as soon as he could recover from the shock. “But why did you fire over my shoulder like that? It was only a jack-rabbit.”

“I didn’t mean to fire. The gun—hark!”

Harry stopped short and both listened. From a distance they could hear one Indian calling to another. Then followed a crashing through some undergrowth.

“They are after us sure!” ejaculated Harry. “Come on.”

Both broke into a run without waiting for Harry to reload. As they went on, they heard more firing at a distance, and then a long yell that they knew could mean but one thing.

“The Indians are on the warpath!” exclaimed Joe. “There can be no doubt of it—they have attacked the camp.”

[15]“How many do you suppose there are of them?”

“There is no telling. But if they number a dozen or more it will surely go hard with all of our party, Harry.”

They calculated that they had covered half the distance to the camp when they reached something of a hollow. Here the undergrowth was extra heavy and the ground wet and uncertain, and before they realized it they were in a bog up to their ankles.

“This won’t do,” came from Harry. “If we aren’t careful we’ll get in so deep we can’t get out again. We’ll have to turn back.”

“Turn back—with the Indians following us?” said Joe.

“I mean to walk around this hollow, Joe. It’s the only way.”

They turned back to dry ground and then moved to the southward, still further away from the brook. Here was something of an opening, but they avoided this and made for some rocks, gaining a new shelter just as three Indians burst into view.

“Keep to the rocks,” whispered Joe. “Don’t leave a trail if you can help it—and get away as far as possible from this place!”

He went on, over the rocks, and Harry followed.[16] The way led deeper and deeper into the forest and soon the light of day was shut out entirely.

Both were now out of breath and glad enough to climb into a dense tree and rest. As they sat among the upper branches they listened intently for more signs of the Indians, but none reached them. Once Joe fancied he heard a cry in English at a great distance, but he was not certain.

“This is a pickle truly,” observed Harry, after a long spell of silence.

“It is what we get for straying away too far from camp,” returned Joe bitterly. “Father warned me to keep near, and he warned everybody else, too.”

“What do you say we should do next?”

“I hardly know, Harry. If we start to go on those Indians may be laying low for us.”

“Do you want to remain in the tree all night?”

“We may have to remain here all night. If we start out after it is real dark we may become hopelessly lost in the timber.”

“But the redskins can spot us twice as quick in the daylight as they can now.”

“I know that as well as you.”

After this came another long spell of silence, in which each boy was busy with his thoughts. The mind of each dwelt upon the camp. Had it been[17] attacked, and if so had any of the loved ones been slain?

As night came on they heard strange sounds in the forest, sounds which would have frightened youths less used to woodcraft. From the hollow came the mournful glunk of frogs, and the shrill tweet of tree toads. All around them the night birds uttered their solitary notes, punctuated ever and anon with the hoot of an owl. And then they heard the rustling of underbrush as various wild animals stole from their lairs in quest of prey.

“I am going to climb to the top of the tree and see if I can locate the camp-fire,” said Harry, at length. “If that is burning as usual it will be a sign that nothing very wrong has happened.”

Leaving his gun hanging on a limb, he commenced to climb from one branch to the next. Joe was about to follow but concluded that it would be best for one to remain below on guard, for the top of this giant of the forest was fully eighty feet above the position he now occupied.

The climbing of such a tree is by no means an easy task. As Harry approached the top he found the branches further apart and quite slender, and he had all he could do to haul himself from one safe position to another above it.

His activity was rewarded at last, and he stood on a limb which gave him a free and uninterrupted[18] view of the country for miles around. There was no moon, but the sky was clear, and countless stars served to brighten the early night. Far to the westward the clouds were still red from the setting sun.

Eagerly the youth turned to where he imagined the camp-fire of the pioneers must be located. Not a single light came to view, either camp-fire or lantern.

“That is certainly queer,” he told himself. “Not a flare of any kind.”

The thought had scarcely crossed his mind when his attention was attracted to a location about half a mile to the northward of the camp. The light of a torch had blazed forth and was now revolving rapidly in a semicircle.

“An Indian signal,” he muttered softly. “I wish I knew what it meant.”

The light was waved in a semicircle for fully half a minute. Then it bobbed up and down twice and vanished.

Scarcely had this light gone from view than Harry noticed another light, this time on the other side of the pioneers’ camp. This new light was bobbing up and down at a rapid rate, making it look almost like a streak of fire. Then it changed from side to side, and then to a circle. Inside of three minutes it was gone.

[19]“If one could only read the Indian signs it might prove a big help,” mused the boy. “Perhaps I had better stay up here to-night and see if any more signs are made. Then, if we get back to camp in the morning, I can ask old Pep Frost what they mean.”

He sat in a crotch of the limb for the best part of half an hour. The position was far from comfortable, and he was on the point of changing it when he heard a noise some distance below.

“Is that you coming up, Joe?” he asked softly.

A low hiss of warning was the only reply, and Harry knew at once something was wrong. He leaned far down and presently made out his companion, coming up slowly and noiselessly and carrying both of the guns.

“What is it?” he asked, when he could get his mouth close to Joe’s ear.

“Three Indians are in the forest, close to the bottom of this tree,” was the answer. “Don’t make a sound or we’ll be discovered—if we haven’t been spotted already.”

The announcement that Joe Winship made filled Harry Parsons with renewed fear. The three Indians in the forest below them must surely be on their trail, and for no good purpose.

In a low whisper Harry related what he had seen, and Joe agreed that they were Indian signals.

“More than likely they are surrounding the camp,” whispered Joe. “And as you didn’t see the camp-fire likely the folks are on guard. They are not going to make a light for the redskins to shoot by.”

This was all that was said for a long time. Joe passed up his companion’s gun and both sat in readiness to defend their lives at any instant it might become necessary to do so.

Presently the low murmur of voices came to their ears from the very root of the tree in which they were in hiding. Two Indians had met there and were discussing the situation.

[21]“What are they saying?” whispered Harry, for he knew that Joe had learned considerable of the Indian tongue, both from some friendly red men and from his father.

“I can’t hear clearly,” replied Joe. “I might go down a little further.”

“Don’t do it—it isn’t safe,” was his companion’s warning.

But Joe was curious, and as the murmur of voices continued, he noiselessly lowered himself until he was halfway down to the roots of the monarch of the forest.

Leaning over a limb, he strained his ears to catch what was said. The dialect of the red men was somewhat new to him, yet he caught the words “camp of the palefaces,” “Long Knife has commanded it,” and a little later “his scalp shall be mine.”

It was a good half-hour before the Indians moved away, having been joined by three others. All were in warpaint, as Joe could see by a smoky torch which one of the number carried. Luckily the Indians had tramped around the bottom of the tree so much that the trail of the two youths was completely obliterated.

When Joe returned to where he had left Harry, the pair discussed the situation in an earnest whisper.

[22]“The whole thing is clear in my mind,” said Joe. “Long Knife has ordered a raid on our camp, and one of the redskins has a particular grudge against one of our crowd and is going in to get his scalp. The question is: what are we to do?”

“What can we do, Joe?”

“I don’t know what we can do, Harry, but I know what we ought to try to do.”

“Get back to camp and warn everybody?”

“Yes. Of course I think they are on guard already, but we are not sure of it. And if the redskins fall on them by surprise they’ll kill all of the men folks, and kill the women and children too, or carry them off.”

“Then let us try to get back to camp, no matter how perilous it is.”

“I’m willing.”

It was not long after this that they were on the lowest branch of the tree. They strained eyes and ears for some sign of the Indians, but none appeared. Joe was the first to drop to the ground, and Harry speedily followed.

From the top of the tree they had “located themselves” with care, and now they struck out in the darkness directly for the camp.

“We are taking our lives in our hands,” was the way in which Joe expressed himself. “But it[23] cannot be helped. I don’t want to see the others suffer if we can do anything that will save them.”

“Right you are, Joe,” was his companion’s reply.

Fortunately for the boys there was but little undergrowth in that portion of the great forest, and the ground was comparatively level. The trees, five to fifteen feet apart, grew up tall and as straight as so many arrows. Some had stood there for many, many years, and it did not seem possible that these veterans were later on to fall beneath the stroke of the woodman’s ax, to make way for the farmer and his crops.

But if brushwood was wanting, exposed roots were not, and more than once one boy or the other would go sprawling in the darkness.

“By George, what a fall!” panted Harry, after a tumble that had laid him flat on his breast. “It—it knocked the wind right out of me.”

“Be glad it didn’t knock out your teeth,” answered Joe, as he assisted him to his feet. “It is dark here for certain.”

“How far do you suppose we have still to go?”

“Not less than half a mile.”

A moment after this a distant shot rang out, followed by several others in quick succession.

[24]Then came a muffled yell, which gradually became louder.

“The attack on the camp has begun!” ejaculated Joe. “Oh, Harry, we are too late!”

“You are right. More than likely the camp is surrounded.”

“Then we can’t get to the others even if we try!”

“Perhaps we can. Anyway I am not going to stay here when the others may be fighting for their lives. Think of your mother and mine, and of the girls.”

“Yes! yes!” Joe gave a groan which was echoed by his companion. “We must go on.”

And on they did go, running as fast as the trees and the darkness permitted. The land sloped slightly upward, but this they did not notice until Harry, who was slightly in advance, gave a cry of alarm. Then followed a crash of brushwood and a splash.

“Harry! Harry! what’s the matter?” asked Joe, and came to a halt.

No answer came back, and filled with added fear Joe crawled forward until he reached the brushwood. Then of a sudden he took a step backward. The brushwood was on the edge of a cliff and in front was a sheer descent of fully fifty feet.

[25]“Harry went over that and most likely broke his neck,” was Joe’s first thought, and a shiver passed down his backbone. Then he remembered having heard a faint splash, and crawling forward on hands and knees, peered over the cliff into the darkness beneath.

At first he could see nothing. But then came a faint twinkling of stars as they were reflected in the surface of the water, and he knew that a pond or a stream lay at the bottom of the cliff.

“Harry! Harry!” he called out, first in an ordinary tone and then louder and louder. For the moment his own peril was forgotten in his alarm over the disappearance of his chum.

No answering cry came back, and again Joe shivered. What if his companion was drowned?

“I must get down to the bottom of the cliff,” he told himself. “And the sooner the better. Harry may not yet be dead.”

With extreme caution the young pioneer moved along the edge of the cliff, not leaving one footing until he was sure of the next. By this means he discovered something of a break, and here let himself down, foot by foot. The route was rough, and more than once he scratched his face and hands, but just then he gave no attention to the hurts.

Luckily for Joe there was at the foot of the[26] cliff a small stretch of rocks and sand less than a yard wide. Standing on this the youth surveyed the surface of the dark water before him with interest.

It was no pond to which he had descended, but a good-sized stream which flowed rapidly to the northward, being hedged in on one side by the cliff, and on the other by a rock-bound forest. The stream disappeared around a curve of the cliff.

A rapid search along the sandy shore under the cliff revealed nothing more than Harry’s rifle, which had caught in a bush just over the water’s edge. This gave Joe a clew to where his companion had fallen, and he searched eagerly in the water at that point.

“Not a sign,” he murmured after reaching into the stream as far as possible. Then he cut down a sapling with his hunting knife and stirred up the water with that, and with no better result.

“The river is flowing so swiftly it must have carried Harry’s body away,” he reasoned. “Perhaps I had better move around the curve of the cliff and make a search there.”

All this while Joe had heard distant firing and yelling, and now, as he straightened up, he saw a glow in the sky, as of a conflagration.

“Something is on fire,” he thought. “And it[27] isn’t a plain camp-fire either. Oh, I trust to Heaven that the others are safe!”

Slowly and painfully he crawled along at the foot of the cliff until the bend was reached. Here a footing was uncertain, and more than once he slipped into the stream up to his ankles.

Around the bend the water swirled and foamed, on its way to a series of rough rocks. Here was another cliff and the stream appeared to disappear beneath this, much to Joe’s wonder.

“If it’s an underground river good-by to poor Harry,” he told himself.

Again he called out, not once, but a score of times, and the only answer he received was an echo from the rocks.

“Poor, poor Harry!” he murmured, and the tears of sorrow stood in his eyes. He loved his chum as though the two were brothers.

Joe knew not how to proceed. He wanted to find Harry, and he also wanted to learn how his folks and the others were faring at the camp.

While he was meditating he saw the flare of a torch on the opposite side of the stream. He had just time enough to drop behind an outstanding rock when three Indians came into view. Each carried a bundle, but what the loads contained Joe could not tell.

From a hiding place beneath the trees the Indians[28] brought forth a large canoe and two paddles. They placed their loads into the craft, and then entered themselves.

“Can they be coming over here?” Joe asked himself.

The question was soon answered in the negative, for the Indians turned up the stream. It was a difficult matter to paddle against the strong current, but the red men were equal to the task, and soon the canoe disappeared in the darkness.

“I’ll wager all I am worth those were things stolen from our camp,” reasoned Joe.

He sat down at the water’s edge to listen and to think. All had become quiet in the distance, and the red glow in the sky was dying away.

“I must do something,” he cried, leaping up. “If I stay here I’ll go crazy. Perhaps mother and father and the others need me this very minute.”

As quickly as he could he made his way along the rocks to the point where the stream disappeared under the cliff. Then he worked his way around to where the Indians had launched their canoe.

“There must be some sort of a route from this point to our camp,” he told himself.

He was about to move onward through the forest when another torch came into view. Again[29] he ran for shelter, and was not an instant too soon. Four red men were marching forward to the river, and between each pair was a captive, disarmed, and with his hands tied tightly behind him.

“Pep Frost!” murmured Joe, as he caught a good look at the first of the captives. It was indeed the pioneer the youth had mentioned. His garb was torn and dirty, and his face streaked with blood, showing that he had fought desperately.

The second captive was also dirty and bloodstained, and walked with a limp, as if wounded in the left leg. As he came closer Joe could scarcely suppress a cry of horror.

“Father!” he gasped, and he was right. The second captive was Ezra Winship.

“Oh!”

That was the single cry which Harry uttered as he plunged over the edge of the cliff into the stream below.

As he went down his gun was torn from his grasp by the bushes, and an instant later he struck the stream with a splash and went down straight to the bottom.

The breath was knocked out of him by the fall, and when he came again to the surface he was more than half unconscious. He felt himself borne along by the current, and there followed a strange humming in his ears. Then his senses completely forsook him.

When Harry was once more able to reason he knew little outside of the fact that he had a severe headache, and that all was pitch-dark around him. He lay in a shallow pool with the swiftly flowing river within an arm’s length. Absolute darkness was on all sides of the youth.

For a long time he lay still, gasping for breath[31] and putting his hand feebly to his forehead. Then he sat up and stared about in bewilderment.

“Joe!” he stammered. “Joe!”

Of course there was no answer, and then Harry slowly realized what had happened—his rapid run through the forest, his coming to the cliff, and his unexpected plunge into the river beneath.

“I’m still in the water,” he thought. “But where?”

This question he could not answer, nor could he explain to himself how it was that he had not been drowned. But with even so much of peril still around him he was thankful that his life had been spared.

Feeling cautiously around the pool, he soon learned which side sloped to the river, and which toward a sandy underground shore, and slowly and painfully he dragged himself up to the higher ground.

“I am not at the cliff, that is certain,” he mused, as he tried to gaze upward. “I can’t see a star.”

The conviction then forced itself upon him that he was underground, and this being so he quickly came to the conclusion that the flow of the river had carried him to this locality. But how far he was from the spot where he had taken the fall he could not imagine.

He was too weak to travel, or even to make an[32] examination of his surroundings, and having moved around a distance of less than a rod along the bank of the underground stream he was glad enough to sink down again to rest.

As Harry sat there, his head still aching, his mind went back to Joe.

“I suppose he thinks I am dead,” was his dismal thought.

Slowly the time wore away and Harry sat in something of a doze, too weak to either move or speculate upon his condition, very much as one does who is recovering from a long spell of sickness.

Thus the night wore away and morning came to view outside, with clear warm sunshine and singing birds. But in the cavern the darkness remained as great as before.

At last Harry felt that he must do something for himself. He was beginning to grow hungry, and he knew that many hours had passed since he had taken the plunge into the stream.

“I must see if I can’t follow the river back to where it ran under the rocks,” was what he told himself. “That ought o bring me back to the cliff, and perhaps I’ll find Joe looking for me.”

With extreme caution he felt of the water, to find in what direction it was flowing, and then[33] essayed to follow the stream up its course between the rocks and along the sandy beach.

It was a difficult task, and more than once he had to stop to get back his strength. At certain points he had to climb rocks which were sharp and slippery, and twice he fell into the stream and pulled himself out only with much labor.

And then came the bitterest moment of all, when he reached a point where the beach came to an end and found that the opening further up the stream was completely filled with water, which roared onward, dashing the spray in all directions. Here Harry could see a faint gleam of daylight, but only sufficient to show him how completely he was a prisoner.

“I can’t get through that,” he muttered. “If I try it I’ll surely be drowned.”

But if he could not get through what was he to do? To remain where he was would be to starve like a rat in a trap.

“Perhaps the stream leaves this cave at the other end,” he reasoned. “But that may be a long way from here.”

There was no help for it, and with slow and painful steps he retraced his way along the underground river bank, often falling over the rough rocks and stopping every few rods to rest and get back his breath. He was now hungrier than ever,[34] and eagerly gnawed at a bit of birch wood which he happened to pick up out of the water as he moved along.

As Harry journeyed onward, he came to a sharp turn of the stream. Here the water appeared to divide into several parts, and two of these sunk out of sight amid the rough rocks on all sides. A small stream flowed to the left. From some point far overhead a faint light shone down, just sufficient to reveal the condition of affairs to the youth.

“What a cave!” murmured Harry to himself, and he was right. It was certainly a large opening, but nothing at all in comparison to the great Mammoth Cave of that territory, discovered some years later, and which covers many miles of ground. The roof was fully fifty feet above the young pioneer’s head, and the walls were three or four times that distance apart.

Having even a faint light made walking easier, and once again he went onward, following the single stream that remained in sight. Twice he heard a rush of birds over his head, which made him confident that the open air could not be far off. The cave turned and twisted in several directions, and at last he saw sunshine ahead and fairly ran to make certain that he had not been deceived.

[35]When he was really out into the open air once more, Harry sat down on the grass, trembling in every limb. To him the time spent underground seemed an age. Never before had the sun and the blue vault of heaven appeared to him so beautiful.

But it was not long before the pangs of hunger again asserted themselves. He had already taken note of some berry bushes, and he hobbled to these and ate what he wanted of the fruit. They stilled the gnawing in his stomach, but did not satisfy him.

In his pocket the young pioneer had some fishing lines and several hooks, and also a box with flint and tinder. He laid the tinder out to dry on a warm rock, and then with the line went to fishing, after having turned up some worms from under a number of small stones.

His catch of fish amounted to little, but soon he had enough for a single meal, and then he made himself a tiny fire. He could hardly wait to cook the fish, and it must be confessed that he gulped them down when still half raw,—for Harry’s appetite had always been of the best, and in those days pioneers did not dare to be over-particular concerning their food.

By the position of the sun Harry judged that it was nearly noon. As the orb of day was almost[36] directly overhead it was next to impossible for him to locate the points of the compass.

“If I felt stronger I would climb a tree and take a look around,” he told himself. But he was still so shaky he felt that there would be too much danger of falling.

A grassy bank close to where he had cooked the fish looked very inviting, and he threw himself upon it to rest—for just about ten minutes, so he told himself. But the ten minutes lengthened into twenty, and then into half an hour, and soon he was sleeping soundly, poor, worn-out Nature having at last claimed her own.

When Harry awoke he felt much refreshed, and his headache was entirely gone. He sprang to his feet with an exclamation of surprise, for the sun was setting over the forest in the west.

“I must have slept all afternoon,” he murmured ruefully. “Well, I reckon I needed it. But I should have been on my way before dark.”

He now felt more like climbing a tree, and was soon going up a tall walnut that stood on a slight hill near by.

From the top a grand panorama of the rolling hills of Kentucky was spread out before him—that captivating scene which had but a few years before so charmed Daniel Boone and other pioneers who had entered that territory. Here and[37] there a stream glistened in the setting sun, and at one point Harry could see an open stretch of grass with a small herd of buffalo grazing peacefully, while at another point, evidently a salt-lick, several deer were making themselves at home. As Daniel Boone had said, it was truly the land of plenty.

But Harry’s mind was just then centered upon but two things—to find Joe and to get back as soon as possible to the camp,—provided anything was left of the latter, which was questionable. As he thought of the Indians he shook his head doubtfully.

“They won’t give up this land to us if they can help it,” he told himself. “They will fight for it to the bitter end. For all I know to the contrary, all of the others, including Joe, may be either dead or prisoners.”

From his position in the tree Harry tried to locate the camp which he had left the morning before, but all he could see was a smoldering fire far in the distance.

“That looks as if it might be where the camp was,” he reasoned.

Descending to the ground once more he determined to make his way in the direction of the smoldering fire. Before setting out he cut himself a stout club. He mourned the loss of his[38] gun, and wondered what he should do if confronted by the Indians, or by some wild beast.

But the forest seemed deserted, and he passed a good quarter of a mile without meeting anything but a few rabbits and a fox, and these lost no time in getting away.

The sun was already out of sight behind some trees when he struck another brook, that upon which the fated camp had been located. Here he stopped for a drink, getting down on his hands and knees for that purpose.

Having satisfied his thirst, Harry was on the point of rising, when a noise behind him attracted his attention. He whirled around, to discover a big black bear moving on him with great deliberation.

“Hi! get back there!” he yelled and swung his stick at the beast. He did not mean to throw the object, but it slipped from his hand and, sailing through the air, struck bruin fairly and squarely on the nose.

At once the bear let out a snort of pain and then an added snort of rage. His den was in that vicinity, and, thinking the youth had come to invade it, he arose on his hind legs and came for Harry in a clumsy fashion.

There now remained but one thing for the young pioneer to do, and this he did without stopping[39] to regain the club. He started off on a run up the brook.

The bear immediately dropped down on all fours and came after him. Although totally unconscious of it, Harry was running directly for the bear’s den. This enraged the beast still more, and he did what he could to close the gap between the boy and himself.

The bear was almost on top of Harry when the young pioneer came to a wide-spreading tree with low-hanging branches. One of the branches was within easy reach, and as quick as a flash the youth swung himself up, just as bruin made a leap for him. The bear caught him by the toe, but the boy’s foot-covering gave way and the beast fell back.

Harry lost no time in climbing higher up in the tree. Then he made his way to the trunk, and, hanging to one of the limbs, drew his hunting knife and waited for the bear to climb up.

For the moment after making the discovery that the two captives in the hands of the Indians, were his father and Pep Frost, the old pioneer, Joe Winship could scarcely believe the evidence of his senses.

“Father!” he repeated hoarsely. “Father and Pep Frost!”

The sound of his voice reached one of the Indians, and the red man gazed around sharply. But Joe was wise enough to drop out of sight behind some brushes, and the Indian continued to move on, doubtless thinking that it was merely the wind that had reached his ears.

The two captives were marched down to the river front, and here another canoe was brought to light, similar to that used by the three Indians who had gone off with the three bundles.

“Whar are ye a-going to take us?” Joe heard old Pep Frost ask.

For answer one of the Indians raised his palm and struck the pioneer across the mouth.

[41]“No talk now,” he said laconically.

The two captives were forced into the canoe, one being placed at the bow and one at the stern. Then two of the Indians took up the paddles and started up the stream, in the direction pursued by the first canoe.

Joe watched the proceedings with interest, but when the canoe began to disappear from sight his heart sank within him.

“If I could only follow!” he thought.

But to run along the river bank and thus keep the craft in sight was out of the question. The Indians were experts at using the paddle, and the shore of the stream was, as we already know, rough and uncertain.

Suddenly the youth was seized with a new idea. If there had been two canoes secreted in the bushes why not perhaps a third?

“I’ll hunt around and see,” he muttered, and began the search at once.

In a tiny cove he found just what he wanted, a small canoe boasting of a single paddle. Without hesitation he leaped into it, took up the paddle, and pushed the craft out into the river.

Joe had spent many of his boyhood days on the rivers near his home and could row and paddle just as well as he could shoot and ride on horseback. If it had but a single paddle, the craft[42] was correspondingly light, and by working with vigor he managed to keep the larger canoe within easy distance, although being careful to keep out of reach of the enemies he was following.

As he worked at the paddle his thoughts were busy. What did the capture of his father and Pep Frost mean? Was it possible that the fight at the camp had ended in a general massacre of the others? Such a dire happening was not an impossibility. He remembered that only the summer before the Indians had fallen upon one Jack Flockley and his companions, six in number, and murdered all but one young girl, who had been carried off into captivity.

“I must save them if I possibly can,” he reasoned. “I’ve got my hunting knife and my gun, as well as this gun of Harry’s. They will all come in handy if I can but cut their bonds.”

Fortunately for Joe the Indians kept their torch burning, as a signal for those who had gone on ahead. Two turns of the stream were passed when they came in sight of another torch, waving to and fro on the left bank of the river. At once the canoe turned in that direction, and presently a landing was made at a point where those in the first canoe had gone ashore.

By the light of the two torches Joe saw all of the Indians assembled, with their captives and[43] their bundles between them. He allowed his own little canoe to drift past the landing and then came ashore in the midst of some brushwood overhanging the stream.

By making a détour the young pioneer presently came to the rear of the enemy. He found that they were going into something of a camp and that they had already tied the two captives to separate trees some eight or ten feet apart. Between the two trees squatted a young warrior, placed on guard over the whites.

Scarcely daring to breathe, Joe crept closer and closer until he was less than five yards away from where his father stood, hands and feet fastened to the tree by means of a stout grass rope. For the present he did not dare go closer, but, lying full length in the grass, watched the Indians as a hawk watches a brood of chickens.

The red men were much interested in the contents of the bundles brought hither in the first canoe. Torches were stuck up in convenient places and the bundles were unrolled, revealing to Joe many of the smaller articles which the pioneers had been bringing westward on their pack horses. There was a dress belonging to his mother, a pair of slippers belonging to his sister Harmony, and a razor that he knew belonged to his father. The sight of the razor tickled the fancy of one of the[44] Indians, and flourishing it in the air he approached Pep Frost and made a motion as if to cut the throat of the old pioneer.

“Oh, I reckon ye air ekel to it,” snorted Pep Frost. “You are a cowardly, miserable lot at the best!”

There was a small mirror in one of the bundles, and this pleased the red men more than did any other object. Running up to a torch, one after another would gaze into the mirror with expressions of wonder and admiration. Even the young warrior on guard wanted to look into the glass.

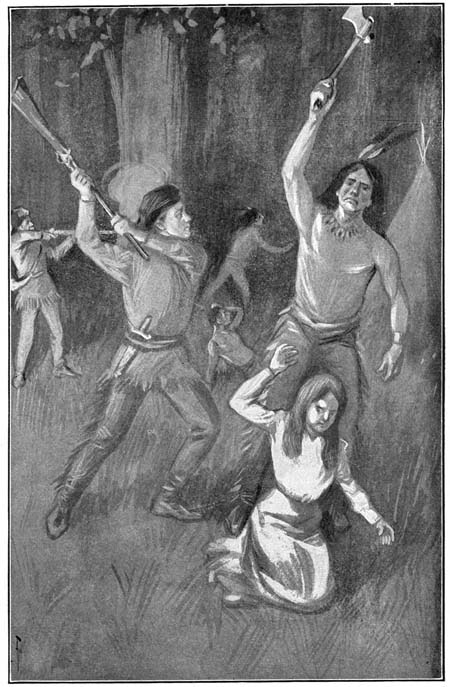

For the moment the prisoners were forgotten and, struck with a sudden determination, Joe crawled close up behind his father and cut the grass rope that bound the parent. Then he placed one of the guns into Mr. Winship’s hand.

“It is I, Joe,” whispered the boy. “Wait till I free Pep Frost.”

“Be quick, and be careful,” returned the astonished man in an equally low tone. And he added: “Are you alone?”

“Yes.”

No more was said, and crawling backward Joe made his way to the tree to which Pep Frost was fastened. Two slashes of the knife and the old pioneer was also liberated, and Joe provided him with the second musket.

[45]“Cut tudder man loose,” whispered Frost, as he fingered the gun nervously.

“He is free,” answered Joe.

So far the captives had not moved from their positions against the trees, and as the young warrior looked at them he imagined each as secure as ever. The Indians in general continued to look over the contents of the bundles until a light on the river caused a fresh interruption.

A third canoe was approaching filled with Indians and with at least two captives. The latter were evidently females, and one, a girl of twelve or fifteen, was crying piteously.

“Let me go! Please let me go!” she begged. “Oh, where are you taking me?”

“Better be quiet, Harmony,” said the woman in the canoe. “It will do thee no good to weep.”

“Harmony!” groaned Joe. “Harmony and Mrs. Parsons! Where can sister Cora be, and Harry’s sister Clara?”

All of the Indians had turned to the river front, and now Pep Frost made a motion to Ezra Winship. The pioneer understood, and, like a flash, both turned and fled into the forest, calling softly to Joe to follow.

Before the Indians discovered their loss the former captives were a good hundred yards away.[46] They kept close together and Joe was by his father’s side. Presently a mad yell rent the air.

“They’ve found out the trick,” came from Pep Frost. “But I reckon as how we’ve got the best o’ ’em, Joey—and thanks to your slickness.”

“Did you see those in the canoe?” queried the youth. “Mrs. Parsons and Harmony!”

“Harmony!” ejaculated Mr. Winship, and stopped short. “Are you sure?”

“Yes, father; Mrs. Parsons called her by name.”

“Then I had best go back——”

“No, no!” put in Pep Frost. “It would be worse nor suicide, friend Winship.”

“But my daughter—the redskins will——”

“I know, I know! But we must bide our time,” interrupted Pep Frost again. “Remember, there were seven redskins on shore and at least four more on the river. We can’t fight no sech band as thet.”

They had reached a small brook, and along this Pep Frost forced the father and son, more than half against their will. Yet both realized that the old pioneer was right—that to fight eleven of the foe under present circumstances would be out of the question.

[47]The Indians were already on the trail and the whites could hear them rushing along the tracks left in the forest. At the brook they came to a halt and then the force divided, some going up the stream and some down.

“I—I can’t walk much further,” came presently from Ezra Winship.

“By gum! I forgot about that wound in your leg,” exclaimed Pep Frost; “but we air a-comin’ to some rocks now an’ more’n likely they’ll afford us some kind o’ a hidin’-place.”

The old pioneer was right, and leaving the brook they crawled up a series of rough rocks and then into a hollow thick with brushwood. Here they felt comparatively safe, and Ezra Winship sank down exhausted, unable to take another step.

While Pep Frost remained on guard to give the alarm should any of the Indians appear in the vicinity, Mr. Winship gave Joe some of the particulars of the attack on the camp of the pioneers.

“We were caught at something of a disadvantage,” said he. “The horses were giving us a good deal of trouble because one of them stepped into a nest of hornets. While the men were trying to calm the beasts the Indians rushed at us without warning.”

[48]“Was anybody killed?”

“Yes; at the first volley Jim Vedder was laid low and Jerry Dillsworth received a wound from which he cannot possibly recover. The Freemans’ baby was also struck in the shoulder while her mother was holding her in her arms. Those who weren’t struck ran for their guns, and we fought the redskins for fully quarter of an hour. But at last the tide of battle went against us, and I was laid low with an arrow wound in the thigh. I went down and a horse came down on top of me, and that was all I knew for about half an hour, when I found myself a prisoner and tied to a tree in the dark.”

“And mother and the girls——”

“I didn’t see anything more of them,” answered Ezra Winship sadly. “I know your mother was hit in the arm by a tomahawk, but I don’t believe the wound was very bad. The last I saw of Pep Frost he was fighting to save Clara Parsons from being carried away. But a blow from a club one of the redskins carried stretched him flat, and when I saw him again he was a prisoner like myself.”

“And what of all of the others, father?”

“I can’t say anything about them for certain, but I imagine about half of them escaped under cover of the darkness, and Pep Frost thinks that[49] at least two men and two women got away on horseback. Besides that, Frank Ludgate was off on a hunt when the attack began, so that it is very likely he escaped too,” concluded Ezra Winship.

Hunting knife in hand, Harry waited for the black bear to mount the tree after him. He knew that if the beast came up he would have the bear at a disadvantage, and he hoped that one good stroke of the long blade would finish the fight.

But the bear did not come up. Instead he halted at the trunk, put his forepaws on the bark, and gazed thoughtfully upward. Then he dropped on his haunches, let out a growl of anger, and sat where he was.

“Don’t want to fight, eh?” mused Harry. “All right, but I hope you won’t stay where you are too long.”

For a while the bear kept his eyes fixed on Harry, as though expecting an attack. But as this did not come bruin lay down at the foot of the tree, resting his head on his forepaws.

This was certainly provoking, for it now looked as if the beast meant to keep the young pioneer a prisoner in the tree.

[51]“Perhaps he thinks he can starve me out,” thought Harry. “Well, I reckon he can, if he keeps me up here long enough. But I don’t mean to stay—not if I can help myself.”

With the hunting knife Harry cut a small limb from the tree and dropped it down on the bear. With a snarl bruin snapped at the limb and buried his teeth into it. Then he leaped up and began to come up the tree in a clumsy fashion.

Harry’s heart thumped madly, for he knew that a perilous moment was at hand. Grasping the hunting knife firmly he leaned far down to meet the oncoming animal.

Bruin was suspicious and evidently did not like the looks of that gleaming blade. When still a yard out of reach he halted in a crotch and snarled viciously. Then he came closer inch by inch.

Leaning still further down Harry made a lunge at the bear. Like a flash up came a forepaw to ward off the blow. Paw and blade met and the bear dropped back a little with the blood dripping from his toes.

But the animal was not yet beaten, and soon he came forward once more, uttering a suppressed snarl and showing his gleaming teeth. He kept his body low down as though meditating a spring.

It came and Harry met it with the point of the hunting knife, which sank deeply into the bear’s[52] right eye. This was a telling blow and the beast let a loud cry of pain. Then the bear dropped back, limb by limb, to the ground.

“That was a lucky stroke,” thought the youth, and he was right. He listened intently and soon heard the bear crashing through the forest and then climbing some rocks leading to his den. With the sight of one eye gone all the fight had been knocked out of him.

Not to be taken unawares, Harry descended to the ground cautiously. But the coast was now clear, and drops of blood on the grass and rocks told plainly in what direction the beast had retreated. Not wishing for another encounter without a gun, the young pioneer moved away in the opposite direction.

“Harry!”

The cry came from the rocks close at hand and made the young pioneer leap in amazement. Looking in the direction he saw Joe standing there, backed up by Mr. Winship and Pep Frost.

“Joe!” he ejaculated, and ran toward his chum.

“Oh, how glad I am to know that you escaped!” exclaimed Joe when they were together. “I thought you were drowned surely.”

“I had a narrow escape,” was the answer.[53] “But where have you been, and what brings your father and Pep Frost here?”

In the next few minutes each youth told his story, to which the other listened with interest.

“You were lucky to escape from that cave,” said Mr. Winship to Harry. “I have heard of such places before but have never seen one.”

From Joe, Harry learned that his chum and the others had been in hiding among the rocks and trees all night and a part of the forenoon, not being able to leave the vicinity because of Mr. Winship’s wounded leg. The Indians had scouted around for them for hours, but without locating them, and they had slipped away to the present location less than half an hour before.

“I must say I am mighty hungry,” said Pep Frost. “An’ if ye don’t mind I’ll follow up thet air b’ar Harry wounded an’ finish him an’ git the meat.”

The others did not object, and the old pioneer was soon on the trail of blood-spots.

“So my mother is in the hands of the Indians,” said Harry, when this news was at last broken to him. “Oh, Mr. Winship, this is terrible! And your daughter Harmony, too! What shall we do?”

“I am going on the trail of the redskins as soon as my wound will permit, Harry.”

[54]“And I am going along,” put in Joe.

“Then I shall go too. I wish we had two more guns.”

In less than an hour Pep Frost came back, bringing with him quite a large chunk of bear meat.

“Had a putty good fight with thet b’ar,” he said. “But the knocked-out eye bothered him a good bit. I knocked out tudder with the gun an’ then the rest was easy.”

In a deep hollow among the rocks a fire was kindled and here they broiled as much of the meat as they cared to eat. This meal was welcome to all and after it was over even Mr. Winship declared that he felt like a new person.

The want of weapons was a serious one, and Pep Frost declared that it was no use going after the Indians unless the two boys were armed with something. He cut for each a strong stick and fashioned it into a bow, and then cut a dozen or more arrows.

“Now try them,” he declared, and when they did so, and found the arrows went fairly straight and with good force, he was delighted.

“’Taint so good as a gun or a pistol,” he said, “but it’s a heap sight better’n nuthin’.”

As some of the Indians had been wounded and killed in the fight, the old pioneer declared that[55] the red men would most likely remain in that vicinity for a week or perhaps even for a month.

“They know well enough that there aint nobuddy to come to our aid,” he said. “So they’ll hang around down by the river an’ give the wounded warriors a chance to patch up thar hurts.”

“And what will they do with their prisoners?” questioned Harry.

“Keep ’em with ’em, more’n likely, lad.”

“Can’t we rescue them in the dark?” asked Joe.

“Jest what I calkerlated we might try to do. But we must be keerful, or else we’ll be killed, an’ nobuddy saved nuther.”

It was late that evening when they started back for the river, Pep Frost leading the way, slowly and cautiously, with Harry’s gun still in hand, ready to be used on an instant’s notice.

The boys had been taught the value of silence, and the whole party proceeded in Indian file, speaking only when it was necessary, and then in nothing above a whisper.

It soon became evident that the clear night of the day before was not to be duplicated. There was a strong breeze blowing, and heavy clouds soon rolled up from the westward.

[56]“A storm is coming,” whispered Joe to his father.

“I won’t mind that,” answered the parent. “It may make the work we have cut out for ourselves easier.”

Soon came the patter of rain, at first scatteringly, and then in a steady downpour. Under the trees of the forest it remained dry for a time, but at last the downpour reached them and they were soon wet to the skin.

“This isn’t pleasant, is it?” whispered Harry to Joe. “But if only it helps us in our plan I shan’t care.”

Before the river was gained they had to cross an open space. As they advanced Pep Frost called a sudden halt and dropped in the long grass, and the others followed suit.

Hardly were our friends flat than several Indians came in that direction, each carrying a bundle, the same that had been opened and inspected the night before. They passed within fifty feet of the whites, but without discovering their presence.

“That was a close shave,” whispered Joe when the last of the red men had finally disappeared in the vicinity of some rocks to the northward.

“Reckon they are striking out for some sort o’[57] shelter,” said Pep Frost. “I’m mighty glad on it, too,” he added thoughtfully.

“Why?” asked Harry.

“Thar was three o’ ’em, lad, an’ thet means three less down by the river a-guardin’ the prisoners.”

“To be sure,” cried the young pioneer. “I wish some more would come this way.”

The storm was now on them in all of its fury. There was no thunder or lightning, but the rain came down in sheets, and they were glad enough when the shelter of the forest was gained once more. They were now close to the river, and in a few minutes reached the spot where Joe had landed in the borrowed canoe. The craft still lay hidden where the young pioneer had left it.

“The canoe may come in very useful, should we wish to escape in a hurry,” said Ezra Winship.

While the others remained at the water’s edge, Pep Frost went forward once again on the scout. Joe begged to be taken along, but the old pioneer demurred.

“No use on it, lad, an’, besides, it’s risky. Sence you helped us to git away them Injuns is sure to be on stricter guard nor ever.”

Left to themselves, the others decided to float the canoe and hold it in readiness for use. This[58] was an easy matter, and Joe remained in the craft, paddle in hand, while Harry and Mr. Winship stood on the river bank on guard.

Thus nearly half an hour went by. The rain came down as steadily as ever, and the sky was now inky black.

“It’s time Pep Frost was back,” said Ezra Winship at last. “I hope nothing has happened to him.”

A few minutes later they heard a murmur of voices in the Indian camp, and then a scream which, however, was quickly suppressed.

“I cannot stand the suspense,” declared Mr. Winship. “Boys, watch out until I get back,” and without further words he followed in the trail Pep Frost had taken.

The scream had excited Joe as well as his father, for he felt that it was his sister Harmony who had uttered the cry.

“I’m going to push the canoe out to the edge of the brushwood,” he whispered to Harry. “I think I can see the Indian camp from that point, if they have any torches lit.”

Noiselessly he shoved the light craft forward until the edge of the bushes was reached. He peered forward cautiously, and then went out a little further. Only the fierce rain greeted him, and the silent river seemed deserted.

[59]At last he caught sight of the flare of a torch, spluttering fitfully in the rain and the wind. It was a good hundred yards away, and he made out the forms of several Indians with difficulty. Then he discovered another torch on the river and saw that it was fastened at the bow of a canoe which had just been set in motion.

“Save me!” came suddenly to his ears. “Oh, save me, Mrs. Parsons. Do not let this horrid Indian carry me away from you!”

“Harmony!” burst from Joe’s lips.

He was right, his sister was in the canoe, held there by the hand of a tall and fierce-looking warrior. With the other hand the red man was using his paddle to force the craft up the stream. As the canoe came closer Joe recognized the warrior. It was Long Knife, the savage chief who had led the attack on the pioneers’ camp.

It filled Joe’s heart with a nameless dread to see his sister being thus carried off by an Indian he knew was as cruel as he was bloodthirsty.

“I must save her,” was his thought. “I must save her, no matter what the cost!”

In haste he shoved his canoe back to the bank and called softly to Harry.

“What do you want, Joe?” asked his chum, in an equally low tone of voice.

In a few hurried words the situation was explained. “Tell father I have gone after the pair,” Joe added.

Without more conversation, Joe started his canoe forward again, and was soon on the river and in pursuit of the other canoe, which was now a hundred yards or more ahead.

By the aid of the torch in the bow he kept Long Knife’s craft in view with ease, while his own canoe was invisible to the red man on account of the rain and the darkness.

[61]As he crept closer Joe could hear his sister begging piteously of the Indian to let her go back to Mrs. Parsons.

“Please, please, let me go back!” cried Harmony. “Oh, have you no heart?”

“White maiden be quiet,” growled Long Knife. “Can talk much after she is in Long Knife’s wigwam.”

“I do not want to go to your wigwam,” moaned the girl. “I want to go back to the lady I was with.”

“Bah! the old Quaker woman does not count,” was Long Knife’s comment. “She is not as good as the squaw that shall take care of the white maiden.”

“I don’t want any squaw to take care of me,” answered Harmony, and then fell to weeping silently.

So far Joe had formed no plan of rescue. Long Knife had dropped his hold of the girl and was now paddling vigorously with both hands, and it was all the young pioneer could do to keep him in sight.

When about half a mile of the river had been covered, they came to a spot where there was something of a lake. Here Long Knife paddled with less speed and Joe came closer rapidly.

In the canoe the youth had the bow and arrows[62] made for him by Pep Frost, and also a stout club he had cut for himself.

“I wish I had a gun instead of the bow,” he thought. “I’d soon knock him over as he deserves.”

Picking up the bow and an arrow Joe adjusted the latter with care. Harmony had sunk to the bottom of the canoe, while Long Knife stood upright, trying, by the flare of the torch, to find a suitable landing.

The canoes were now not over a hundred feet apart. With a strong use of the paddle the young pioneer sent his craft thirty or forty feet closer. Then he leaped to the bow and aimed the arrow with all the accuracy at his command.

Whiz! the arrow shot forth, and had the object at which it was aimed not moved at that instant Long Knife would have received the shaft straight under the shoulder blade. But just then the canoe bumped on a part of the bank that was under water, and the Indian pitched slightly forward, which caused the shaft to graze his shoulder and his neck.

“What is the white maiden doing?” he cried in his native tongue, as he grasped the bow of the canoe to keep from going overboard.

Harmony did not answer, for she did not understand the question. But she saw the arrow[63] before it caught the eye of the Indian, and turning to see who fired it, discovered her brother and set up a cry of joy.

“Oh, Joe! Joe! Save me!”

“I will if I can,” he answered, and reached for another arrow.

By this time Long Knife had recovered and was peering forth into the gloom to learn from what point the attack was coming, and how many of the whites were at hand.

It must be admitted that Joe was excited, and his hand trembled somewhat as he adjusted the second arrow and let it fly without stopping to take a careful aim.

But the hand of Providence was in that shot, and Long Knife was taken fairly and squarely in the breast.

The wound was not a mortal one, but it was enough to take all the fight out of the Indian. With a groan of pain he fell in the bow of the canoe. Then, fearing another shot, or perhaps a blow from a hunting knife, he slipped overboard, staggered ashore, and disappeared in the total darkness of the forest.

“Oh, Joe!” These were the only words that Harmony could utter, but as the two canoes glided together, she arose and threw her arms around her brother’s neck.

[64]Just then the brother uttered no reply to this warm greeting. He had seen Long Knife disappear into the forest, and he did not know but that the Indian might return to the attack almost immediately.

Two steps took him to the bow of the other canoe, and with a handful of water he dashed out the light of the torch. Then he seized the paddle and began to work the craft out into midstream, shoving the other canoe along at the same time.

But Long Knife was in no condition to attack anybody, and soon the dim outline of the shore faded from view. Then Joe tied the smaller craft fast to the larger, and transferred his bow and arrows and club to the latter. He bent over his sister, and in the midst of the wind and the rain he kissed her.

“It was a close shave, Harmony,” he said. His heart was too full to say more.

“Oh, Joe!” She clung to him tightly. “Was it not terrible? Supposing he had carried me off, miles and miles away?”

“Don’t make too much noise, Harmony—there may be redskins all along this river bank.”

“Do you know anything of father and mother?”

“I was with father when I discovered you in the canoe with Long Knife. He and Pep Brown[65] and Harry Parsons were all with me, and we were getting ready to do what we could to rescue you and Mrs. Parsons. I don’t know anything about mother.”

“She was carried off by two of the Indians—Mrs. Parsons saw it done.”

“It’s queer the redskins separated.”

“The attack was made by two tribes, one under Long Knife, and the other under an Indian called Red Feather, a horrible-looking savage with a broken nose.”

“I haven’t seen anything of that savage. But now we had best keep quiet, Harmony, for we are getting close to the Indian camp again.”

Joe was right. Caught by the current of the river the two canoes were drifting down the stream rapidly. The rain still descended steadily although not as heavily as before.

So far no sound had reached them from the vicinity of the camp where Mrs. Parsons was still held a captive, but now a distant shout could be heard, followed by a war-whoop, and then two gun shots.

“Some sort of an attack is on!” cried the boy. “I trust our side wins out.”

“Oh, so do I, Joe. Did you say father and Mr. Frost had guns?”

“Yes, and they most likely fired those two[66] shots. Hark to the war-whoops! The redskins are making it lively. I’d like to know if Harry is in that mix-up.”

Joe turned the canoes toward the river bank, and after a careful survey of the locality discovered the spot where he had left his chum.

“Harry!” he called softly. “Harry!”

No answer came back, and with caution he shoved the leading canoe through the brushwood toward the bank.

“Keep quiet, Harmony, while I try to find out how the fight is going,” he said, and leaped ashore, hunting knife in hand.

“Oh, Joe, don’t leave me,” she pleaded, but he was already gone.

It was an easy matter to crawl to the vicinity of the Indian camp from where the canoes lay hidden. The whooping and the shots had ended as suddenly as they had begun.

Suddenly Joe stumbled over the dead body of an Indian, still warm, and with blood flowing from a wound in the breast. The discovery was a shock to the young pioneer, and he felt a great desire to jump up and fly from the scene.

Hardly had he made this discovery than he ran across Harry, leaning against a tree, gasping for breath.

“Harry,” he cried, and caught his chum just as[67] he was about to fall in a heap. “Where are you hit?”

“Some—somebody struck me in the—the stomach with a—a—club,” was the gasped-out reply. “Oh!” And then Harry sank like a lump of lead.

Without stopping to think twice Joe picked up the form of his chum and started for the canoes once more. It was a heavy load, but the excitement of the moment gave the youth added strength.

“Who is there?” called Harmony, through the rain.

“I’ve got Harry, Harmony. He has been hit with a club.”

“And father and Mr. Frost?”

“I don’t know where they are.”

But scarcely had the young pioneer spoken when there came a rush of footsteps, and Pep Frost appeared on the scene, closely followed by Ezra Winship, who carried the unconscious form of Mrs. Parsons.

“Father!” burst from the girl’s lips.

“My daughter!” ejaculated the astonished parent. “How did you get here? I thought that Long Knife had carried you off in a canoe.”

“So he did, but Joe came after me and brought[68] me back, after knocking Long Knife over with two arrows.”

“Got two canoes, eh?” came from Pep Frost. “By gum, but they air jest wot we need. In ye go, all of ye, an’ quick!”

But little more was said. All leaped into the canoes, taking the unconscious woman and boy with them. Then they shoved off into the river.

They were not a moment too soon, for as the darkness swallowed them up they heard the Indians in the brushwood, running forward and backward along the bank, and calling guardedly to each other. They did not imagine that the whites had the boats, and supposed they must be in hiding, most likely half in and half out of the water.