*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 67235 ***

Transcriber’s Note: Maps are clickable for larger versions.

Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism

Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission

Anthropological Study No. 2

THE CADDO

INDIANS

OF LOUISIANA

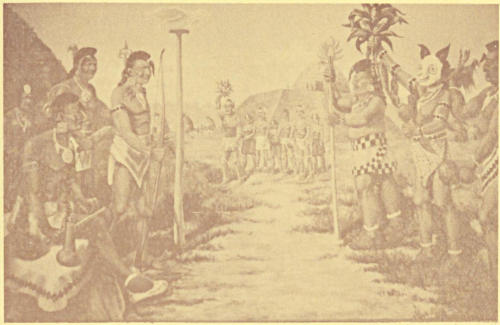

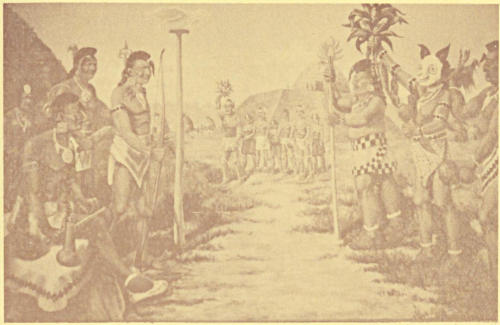

Green Corn Ceremony of prehistoric Caddo Indians.

Presumed village, dress, and utensils about A.D. 1000 as reconstructed

from archaeological findings. Mural in Louisiana State Exhibit Museum,

Shreveport.

Clarence H. Webb

Hiram F. Gregory

August 1978

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

STATE OF LOUISIANA

Edwin Edwards

Governor

DEPARTMENT OF CULTURE, RECREATION AND TOURISM

Dr. J. Larry Crain

Secretary

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND ANTIQUITIES COMMISSION

Ex-Officio Members

| Dr. Alan Toth |

State Archaeologist |

| Dr. E. Bernard Carrier |

Assistant Secretary,

Office of Program Development |

| Mr. William C. Huls |

Secretary, Department of

Natural Resources |

| Mr. Leon Tarver |

Secretary, Department of

Urban and Community Affairs |

Appointed Members

| Mrs. Lanier Simmons |

Mrs. Dale Campbell Brown |

Mr. Thomas M. Ryan |

| Mr. Fred Benton, Jr. |

Dr. Clarence H. Webb |

Dr. Jon L. Gibson |

|

Mr. Robert S. Neitzel |

|

Editor’s Note

More than 10,000 years of human settlement in Louisiana have left a

cultural heritage that is both rich and informative. With the publication of

“The Caddo Indians of Louisiana,” the Department of Culture, Recreation

and Tourism is pleased to continue the series of Anthropological Studies that

will illuminate some of the major episodes in Louisiana’s past.

The two authors of the present study are eminently qualified authorities

on the Caddo Indians. Dr. Clarence H. Webb, a well-known Shreveport

physician, is equally distinguished by his pioneer archaeological efforts in the

Caddoan area. For more than four decades, he has led the professional

community in the illumination of Caddoan prehistory. Dr. Hiram F. Gregory

is Professor of Anthropology at Northwestern State University and also a

veteran of many years of Caddoan archaeology. His professional career,

which began with an exhaustive study of the Spanish presidio of Los Adaes,

has acquired a pronounced ethnohistoric orientation in recent years as the

result of his close cooperation with the Caddo and other living Indian groups.

Recognizing that the past belongs to everyone, and not just to a handful of

scholars, the Anthropological Studies are directed to a general audience. It is

hoped that these studies will bring cultural enrichment to the people of

Louisiana and stimulate an interest in preserving our historic and archaeological

resources for enjoyment and study by future generations.

Alan Toth

State Archaeologist

State of Louisiana

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT

Baton Rouge

Edwin Edwards

Governor

July 5, 1978

CITIZENS OF LOUISIANA

This second edition of the Anthropological Study Series of the Department of Culture,

Recreation and Tourism and the Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission

is dedicated to the late Margaret Elam Drew, a charter member of the Commission.

Affectionately known by professional and amateur archaeologists as “Lady Margaret,” Mrs.

Drew and her close friend, Mrs. Rita Krouse, were instrumental in fostering statewide

governmental and private sector support for the protection of Louisiana’s archaeological

resources.

Mrs. Drew was the wife of Representative Harmon R. Drew of Minden. Her interest in

archaeology began in 1962, with her daughter’s curiosity about the location of Indian tribes in

Northwest Louisiana. Mrs. Drew, a devoted history buff, and Mrs. Krouse enthusiastically

began researching possible Indian sites.

The Drew-Krouse team contacted Dr. William Haag, the Louisiana State University professor

later named as Louisiana’s first State Archaeologist, for advice. Their research marked the

beginning of a fifteen-year partnership of field excursions, field training schools and dedicated

efforts to enlighten the public on archaeology and its importance to everyone.

Webster Parish had no registered archaeological sites in 1962. Through the efforts of Mrs.

Drew and Mrs. Krouse there are now twenty-nine such sites. Claiborne Parish had two

registered sites; there now are twenty-five. Mmes. Drew and Krouse established seventeen

sites in Bienville Parish alone.

In 1974, on Dr. Haag’s recommendation, I was honored to appoint Margaret Drew a charter

member of the Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission. Her appointment

was but a token of her colleagues and my appreciation for her efforts to promote the

establishment of the Antiquities Commission and her work to obtain public and private funds

for archaeological site surveys.

The publication of this study recognizes and honors the late Margaret Drew. Her selfless and

tireless dedication to the preservation of our archaeological resources will, through ages to

come, be credited with helping preserve this precious part of Louisiana’s cultural heritage.

Cordially,

EDWIN EDWARDS

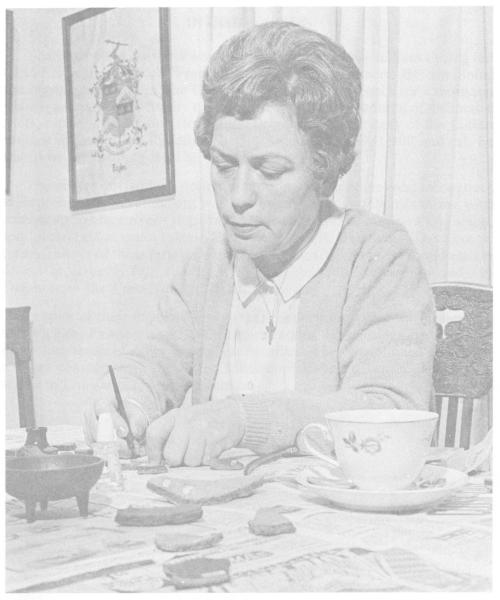

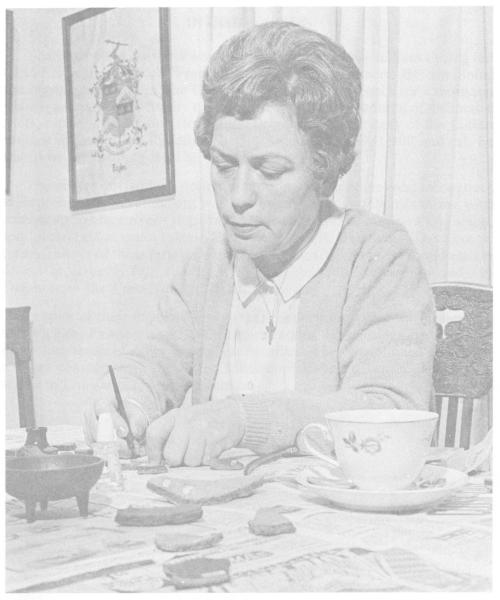

Margaret Elam Drew

(1919-1977)

INTRODUCTION

Northwestern Louisiana was occupied by the Caddo Indians during the

period of early Spanish, French, and American contacts. By combining

history and archaeology, the Caddo story can be traced back for a thousand

years—a unique opportunity made possible by a long tradition of distinctive

traits, especially in pottery forms and decorations. Our story of the Caddo

Indians in Louisiana, therefore, begins around A.D. 800-900 and can be

traced by archaeology well into the historic period.

The center of Caddoan occupation during contact times and throughout

their prehistoric development was along Red River and its tributaries, with

extensions to other river valleys in the four-state area of northern Louisiana,

southwestern Arkansas, eastern Texas, and eastern Oklahoma. The successful

agriculture of these farming peoples was best adapted to the fertile valleys

of major streams like the Red, Sabine, Angelina, Ouachita and—in

Oklahoma—the Canadian and Arkansas rivers.

In spite of their linguistic (language) connections with Plains tribes like

the Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara, the Caddos in Louisiana had customs

much like those of other Southeastern tribes. They maintained trade and

cultural contacts with the lower Mississippi Valley tribes of eastern and

southern Louisiana for many centuries.

[1]

PRE-CADDOAN DEVELOPMENTS

Northwestern Louisiana was occupied for thousands of years before the

beginnings of Caddo culture. In the upland areas, along small streams and

bordering the river valleys, projectile points and tools of Early and Late

Paleo-Indian peoples have been found (Webb 1948b; Gagliano and Gregory

1965). In the western plains, the makers of the fluted Clovis and Folsom

points hunted now extinct types of big game (mammoth, mastodon, sloth)

between 10,000 and 8000 B.C. The later Plainview, Angostura, and

Scottsbluff points have been found with the extinct large bison. Since all of

these distinctive projectile point types have been found in the Louisiana

uplands and mastodon bones, teeth, and tusks have been found in Red River

Valley, big game hunting was possible in the state. However, no camp or kill

sites of Paleo-Indian people have been found thus far.

The oldest camp sites in the Caddo area of northwestern Louisiana are

those of the San Patrice culture, thought to date between 8000 and 6000 B.C.

This culture, which some students look upon as late Paleo-Indian and others

as early Archaic, was named for a stream in De Soto and Sabine Parishes

(Webb 1946). When a camp site of two bands of San Patrice people was

excavated south of Shreveport (Webb, Shiner and Roberts 1971), only their

typical points and a variety of small scraping, cutting, and drilling stone tools

were found. The tools indicated that they still depended largely on

hunting—probably deer, bear, bison, and smaller animals—with a gradual

increase in reliance on gathering wild plant foods. Stone points and tools of

San Patrice people have been found over much of the terrace and upland

parts of Louisiana.

A combination of hunting, fishing, and gathering of native foods by bands

of people, whom we call Archaic, was characteristic throughout Louisiana

from 6000 B.C. until almost the time of Christ. In favorable locations they

congregated in larger groups, at least during certain times of the year, but did

not form definite year-round settlements. Grinding stones and pitted nut

stones show that Archaic people harvested seeds and nuts, such as hickory

nuts, walnuts, pecans, acorns, and chinquapins (chestnuts). They also made

ground stone celts (hatchets) for wood cutting and polished stone ornaments,

especially beads. They hunted with darts which are heavier than arrows and

were thrown with the atlatl, or throwing stick.

Toward the end of the long Archaic period, by 1500 B.C., the Poverty

Point culture developed in northeastern, central, and southern Louisiana.

Sites of this culture have not been found on Red River, but there are Poverty

Point sites on the Ouachita River and the late Archaic people on Red River[2]

had a few items—soapstone vessels, hematite plummets or bolas weights,

polished or effigy beads—which may have been traded from Poverty Point.

People who lived in small settlements and made pottery appeared in the

area about the time of Christ. Their crude pottery was generally plain and

resembled that of Fourche Maline people in eastern Oklahoma and southwestern

Arkansas. In northwestern Louisiana, the culture is called Bellevue

Focus, named for a small mound site on Bodcau Bayou near Bellevue, in

Bossier Parish (Fulton and Webb 1953). The small conical Bellevue mound

was found to cover flexed and partly cremated burials, and is thought to

represent the beginning of the trait of building mounds as burial commemorations

in this part of the state. There was no sign of cultivated plants,

although the Marksville people of this time may have grown maize (corn) and

squash. Probably, the Bellevue people lived largely as had the Archaic folk,

by hunting, fishing, and gathering of the abundant native foods. At another

half dozen small sites along the Red River Valley margins and on the lateral

lakes, small conical mounds show a culture like that of Bellevue. One of these

in Caddo Parish also had polished stone and native copper beads with

cremated burials. An occasional decorated pottery sherd found at these

Bellevue sites resembles Marksville and Troyville pottery of the lower Mississippi

Valley.

The Fredericks mound and village site, near Black Lake in Natchitoches

Parish, seems to be an outpost or colony of central Louisiana Marksville and

Troyville cultures, probably inhabited between A.D. 100 and 600. A few

scattered sherds at other sites along Red River show a thin occupation or

trade with Marksville, but Fredericks is the only large mound and village site

of this intrusive culture in the area.

The first widespread occupation of northwestern Louisiana by pottery

making, farming people was that of Coles Creek culture. This culture developed

along the lower Mississippi Valley, in Louisiana and Mississippi,

including the lower Red River, starting about A.D. 700. Probably because

their agriculture was more advanced, Coles Creek populations increased and

spread widely, up the Mississippi Valley, throughout northern Louisiana,

eventually into the Caddoan area of the other three states, and even to the

Arkansas River in central Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma.

Coles Creek hamlets and villages were on the river banks, on the lateral

lakes, and on streams in the uplands. Many settlements were larger than in

previous times and large ceremonial centers evolved, some of which featured

mounds around a central plaza. There probably were temples atop the

flat-topped mounds and burials within other mounds. The temples were

either chiefs’ or priests’ lodges, or sacred temples, and ceremonies and[3]

festivals presumably were held in the plazas. Pottery was well made and

hunting was with the bow and arrow which replaced the atlatl and dart in this

area about A.D. 600.

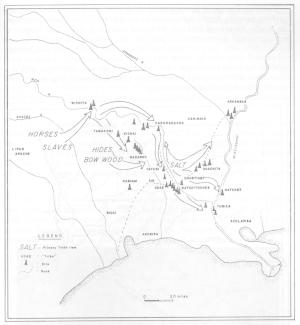

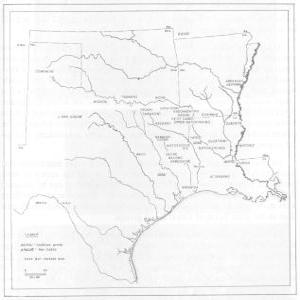

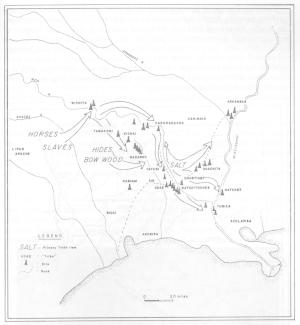

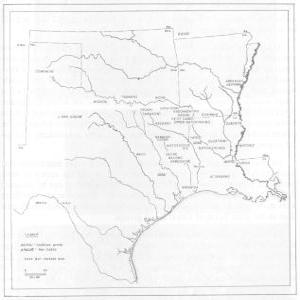

Distribution of principal archaeological sites in northwestern Louisiana. Reprinted with permission of

New World Research and the U.S. Army Engineer District, New Orleans.

[4]

EARLY CADDO CULTURE: ALTO FOCUS

At some time before A.D. 1000, and probably by A.D. 800, the traits

associated with the beginnings of prehistoric Caddo culture replaced Coles

Creek over the four-state area. The change may have started along Red River

in northwestern Louisiana, although others have thought that a group of

“culture bearers” entered the Caddoan area of eastern Texas overland from

the more advanced culture centers of the Mexican Highlands.

Whether the ideas that are shown in the prehistoric settlements came

overland or up the rivers, two conclusions seem certain: (1) early Caddoan

culture existed for a time with late Coles Creek; and (2) Caddo beginnings

added new customs and traits that seem to have originated in Middle

America, especially in the Mexican Highlands and on the upper Mexican

Gulf Coast.

The early Caddo unquestionably derived many things from Coles Creek.

Their settlement patterns were similar, a culture change from Coles Creek to

Caddo often occurring in the same village or even in building levels of the

same mound. The Caddo continued bow and arrow hunting, with identical or

slightly changed stone arrow points. Coles Creek and Caddo peoples practiced

the same kind of intensive maize-beans-sunflower-squash-pumpkin

agriculture or horticulture. They both made clay or stone effigy pipes and

smoked tobacco ceremonially. The Caddo shared many of the Coles Creek

pottery types, especially in the utility vessels, with minor changes taking place

through time, as is to be expected. The Caddo retained strong religious and

civil authority in the villages and the major ceremonial centers and were

organized under a chieftain type of authority. There are similarities to Coles

Creek, finally, in Caddoan ceremonial festivities, games, and customs of

burying the dead in mounds alongside the plazas.

A Middle American origin can be assumed for a number of Caddoan

ceramic ideas. The bottle and the carinated bowl—a bowl with a sharp angle

separating the rim from the sides or the base—vessel shapes are likely

Mexican introductions. The same is true of the low-oxygen firing of pottery

and the burnishing or polishing of the exterior to produce glossy mahogany

brown or black surfaces. Decoration of these surfaces was often by engraving

after firing, combined with cut-out areas and insertion of red pigment into the

designs, and the frequent use of curved line rather than straight line designs.

The curved motifs included concentric circles, spirals, scrolls, interlocking

scrolls, meanders, volutes, swastikas, and stylized serpent designs. A few

curvilinear designs were present in the earlier Marksville and Coles Creek

pottery, but they became more varied and frequent in Caddoan ceramics.

[5]

Another trait introduced from Middle America was that of placing the

burials of important people, such as chiefs, priests, and family members of the

ruling class, in shaft graves, sunk into mounds or special cemetery areas.

Some of the more important early Caddo tombs are quite large, as much as

fifteen to twenty feet in length and eight to sixteen feet in depth. Many had

special sands or pigments on the pit floor, numerous offerings, and indications

that retainers or servants were sacrificed to accompany the revered

person in the afterlife. Shaft tombs in mounds and pyramids occurred in the

Maya areas of Guatemala and Yucatan, and also in the Mexican Highlands,

before and during the time of the early Caddos.

Other Mexican traits were the concepts of the long-nosed god and the

feathered serpent. These symbols are seen in the Caddo area in sheet copper

masks, on carved stone pipes, and on carved conch shells. In Middle America,

the long-nosed god symbol relates to the worship of the rain god, Chaac, and

the feathered serpent is the symbol of Quetzalcoatl (Kukulcan in Maya).

Signs of elaborate ceremonialism have been found in large Caddoan

mound groups or centers in each of the four states: Davis, Sanders, and Sam

Kaufman sites in Texas; Spiro and Harlan in Oklahoma; Crenshaw, Mineral

Springs, Ozan, and East mounds in Arkansas. Along Red River in northwestern

Louisiana, the well-known early Caddo centers are Gahagan and

Mounds Plantation.

The Gahagan site is on the west side of Red River, almost equidistant

between Natchitoches and Shreveport. Formerly it was situated on an old

channel but much of the channel and site have been destroyed by river caving.

A village area, a conical burial mound, and a small flat-topped mound

surrounded a large plaza at Gahagan. Another small mound is about a

quarter mile distant. The burial mound was excavated by Clarence B. Moore

in 1912, and by Webb and Dodd (1939). Moore described a central shaft,

eleven feet in depth and thirteen by eight feet in dimensions, with five burials

and more than 200 offerings. Webb and Dodd found two additional pits

along the slopes, both starting at the mound surface and terminating near the

base. They were nineteen by fifteen and twelve by eleven feet in dimensions,

and contained six and three burials, respectively. Between 250 and 400

offerings were preserved in each pit.

The burial offerings at Gahagan included ornate pottery, beautifully

flaked stone knives (called Gahagan blades), batches of choice flint arrow

points, long stemmed or figurine pipes of clay and stone, copper-plated ear

ornaments, sheet copper plaques, copper hand effigies, long-nosed god copper

masks, polished greenstone celts (some spade-shaped), bone hairpins,

and shell beads or ornaments. All of these are unusual for this area and show

that the early Caddos had widespread trade channels for these esoteric

objects and materials. The sources are as distant as the Gulf coast, the

Kiamichi Mountains of Oklahoma, the central Texas plateau, Tennessee or

Kentucky, and, possibly, the Great Lakes area.

[6]

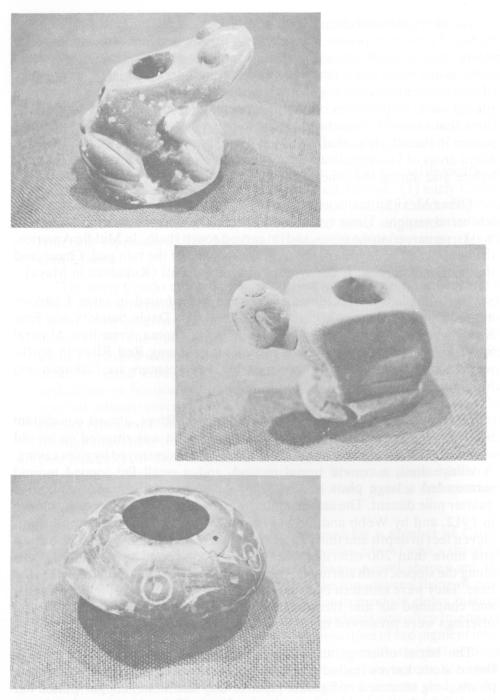

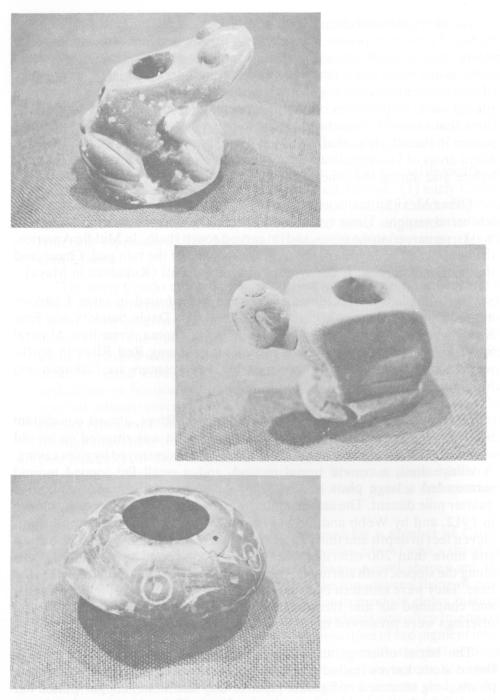

Frog and human effigy stone pipes and polished and engraved pottery vessel made about A.D. 1050.

Artifacts from the Gahagan Mound site, Red River Parish, Louisiana.

[7]

The second Caddo site where high ceremonialism existed is at Mounds

Plantation, on an old Red River channel just north of Shreveport. An oval

plaza, more than 600 yards in length and 200 yards in width (about twenty-five

acres), is surrounded by seven mounds of varying sizes, with two smaller

mounds at some distance. It was first described by Clarence B. Moore (1912),

then studied by surface collections and limited excavations by Ralph R.

McKinney, Robert Plants, and Clarence H. Webb, with assistance of friends

(Webb and McKinney 1975). At least four culture periods were indicated by

pottery sherds. Excavations proved that Coles Creek people established and

laid out the site, probably constructing at least four of the mounds around the

plaza. A flat mound on the northwest corner, started by these people, was

built higher by the early Caddos in what seems to have been a period of rapid

culture change. The mound may have been the location of an arbor or lodge

where food was prepared and served during festivals or ceremonies held in

the adjoining plaza.

At the southeast end of the plaza, the Coles Creek people prepared a

large burial pit, measuring sixteen by fourteen feet, in which they placed ten

adult or adolescent burials in two parallel rows. Offerings found by the

investigators were limited to flint arrow points, bone pins, smoothing stones,

traces of copper-plated ear ornaments, and ankle rattles of tortoise shells

filled with pebbles. A small mound had been built over this pit, and into this

mound later Coles Creek burials had been placed.

Subsequently, the Alto Caddos also used this mound for burials, digging

four large shaft tombs and three smaller pits. All but one of these features

contained offerings of superior quality. The most spectacular of the graves

was a large crater-shaped pit adjoining the Coles Creek pit. It was nineteen

by seventeen feet in dimensions, and was cut through the mound to a depth of

four feet below its base. In it were the skeletons of twenty-one persons, from

elderly adults to unborn infants. An adult male, six feet tall, was provided

with numerous personal effects which included a sheathed knife on his left

forearm and a well-preserved five and one-half foot bow of bois d’arc wood

placed by his left side. He is thought to have been the paramount person

whose death occasioned the immense tomb, the ceremonial offerings, and the

presumed sacrifice of tribal members to accompany him in the afterlife. Part

of the tomb was covered with a framework of cedar logs, thus accounting for

the unusual preservation of many cane and wooden objects.

[8]

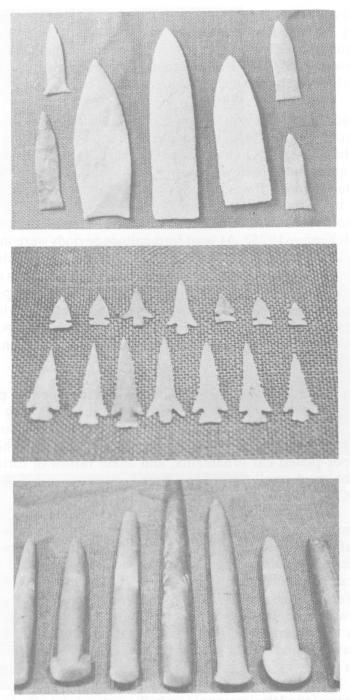

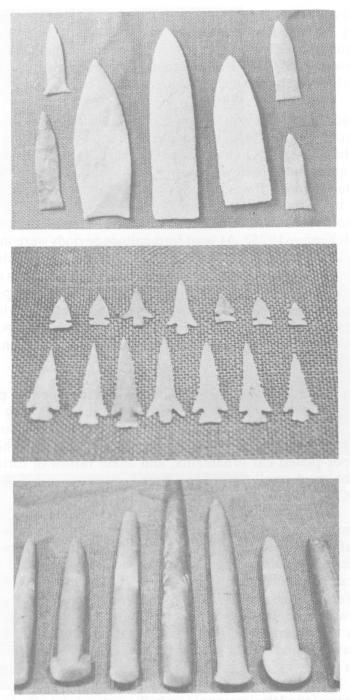

Prehistoric Caddoan stone knives, finely chipped arrow points, and ceremonial polished greenstone celts

from Gahagan Mound site. These Early Caddo artifacts date to the 11th century A.D.

[9]

Preserved offerings included an ornate pottery bowl, decorated with a

thumb-finger cross and eye symbols, flint knives of Gahagan type, fifty-three

arrow points, a long-stemmed pipe, copper-plated ear ornaments, puma

teeth, and objects of wood which included knife handles, a comb, a baton,

several small bows, and wooden frames. Also present were leather, plaited

cording or twine, and about 200 fragments of split cane woven mats, some of

them with diamond or bird head designs. A half pint of seeds beside the

important male were identified later as purslane (Portulaca oleracea), a plant

sometimes used for food by aboriginal people. Also beside the male were

four objects typical of Poverty Point or late Archaic manufacture: two long

polished stone beads, a polished hematite plummet, and half of a perforated

slate gorget. These ancient objects, from a time 2000 years before the Caddo

burial occurred, must have been found and kept as venerated talismans by the

Caddo leaders.

Gahagan and Mounds Plantation have their counterparts as early Caddoan

ceremonial and trade centers at a dozen similar large sites in Texas,

Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The best known is the Spiro mound center on the

Arkansas River in eastern Oklahoma, where enormous amounts of well-made

and exotic objects from the entire midportion of the United States were

gathered or made as offerings. Close contact between these large ceremonial

centers is shown by the similarity of objects, materials, or artistic concepts

across the entire Caddo area. Contacts with other cultural centers in the

Mississippi Valley and into the Southeast also are seen.

Contrasting with these important centers, with their reflection of Middle

American ceremonialism, organized religio-civil leadership class, and expensive

cruel burial ceremonies, there were many small villages and hamlets of

early Caddo people. Their habitations, tools, and some customs are known by

explorations of sites at Smithport Landing (Webb 1963), Allen, Wilkinson,

Swanson’s Landing, and Harrison’s Bayou along the western valley escarpment

(Ford 1936; Webb and McKinney 1975; Gregory and Webb 1965).

Colbert and Greer sites on upland streams in Bienville Parish, and the recent

study of a hamlet at Hanna on the Red River below Gahagan (Thomas,

Campbell and Ahler 1977).

[10]

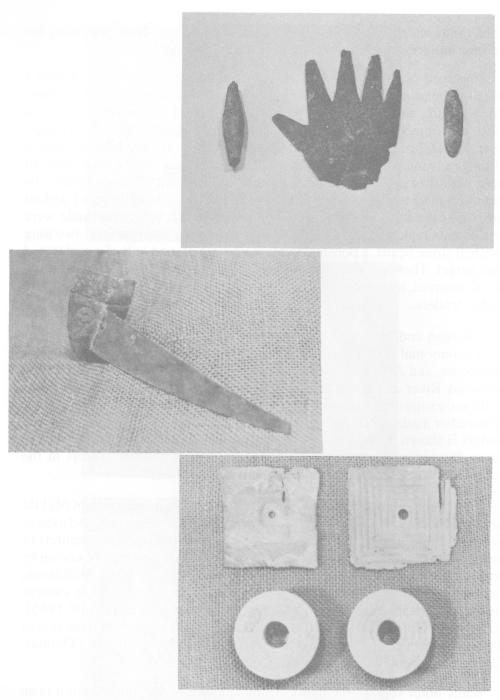

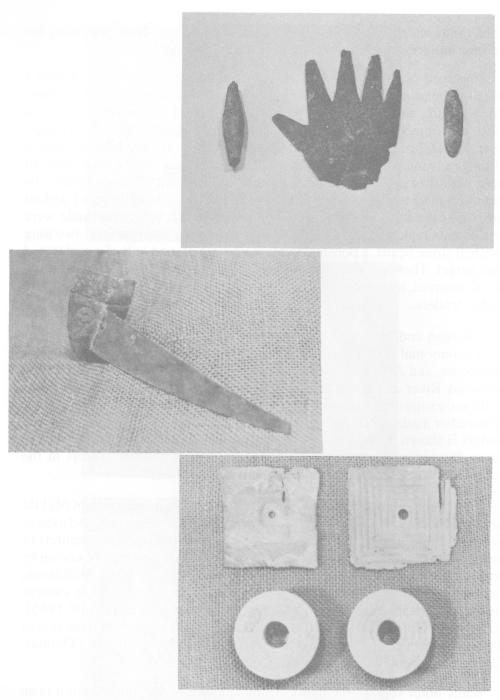

Early Caddo copper objects from Gahagan include beads, a hand effigy, a finger cover, a Long-Nosed God

mask, and copper-plated ear ornaments.

[11]

Many other small settlements of this time are known but have not been

studied, thirty to forty altogether between Natchitoches and the Arkansas

state line (Thomas, Campbell and Ahler 1977; Webb 1975). They are found

in the Red River Valley, on lateral lakes and streams, and in the uplands.

Apparently, these were simple farming, gathering, hunting, and fishing folk

who did not share in the exotic materials of the complex regional centers.

They probably did participate in ceremonies, festivities, and renewals of faith

by visits to the centers and may have provided food, local materials, and

occasional man-power in exchange for leadership and protection. For the

next 500 years there is no evidence of the Caddo being threatened by

outsiders.

BOSSIER FOCUS

Between A.D. 1100 and 1200 the early Caddo culture was changing into

a simpler culture that has been named Bossier, for the parish in which it was

first discovered (Webb 1948a). The large centers faded out or were inhabited

by small groups. The people seem to have been secure, not menaced, and

beginning to spread out along the streams in small settlements or family

homesteads. Local materials were used and few exotic objects have been

found. Burial customs became simpler, usually single graves with a few

offerings and situated near the home or in small cemeteries. The pottery of

the Bossier folk was of good quality and still had some of the decoration by

engraving, incising, and punctating techniques of the earlier period, but

increasing amounts of everyday wares were decorated by simple brushing

(similar to Plaquemine pottery of eastern and southern Louisiana).

Between Caddo Lake and Natchitoches the location of settlements in the

Red River Valley almost disappeared at this time, possibly signifying the

beginning of the Great Raft. The villages and hamlets were on the lateral

streams, lakes, and into the uplands, along virtually every watercourse. A

calm period of pastoral life is indicated and probably lasted until it was

shattered in 1542 by Moscoso’s tattered Spanish army and the subsequent

arrival of other Europeans.

One such hamlet or family homestead of Bossier people is under study at

the Montgomery site in upper Webster Parish at the Springhill Airport

(Webb and Jeane 1977). The people seem to have lived here long enough for

their thatched roof, clay-daubed houses to have been repaired and relocated

a number of times, leaving numerous post molds. Their simple tools and

arrow points were made of local cherts; ornaments are missing and polished

stone tools are rare. Residues of gathered or hunted food stuffs are present:

hickory nuts, acorns, persimmons, mussels, turtle, fish, and deer bones. No

corn, beans, or pumpkin seeds have been found, but they must have grown

these crops and probably did so in gardens rather than in fields. Their pottery,

as shown by broken sherds, ranged from rough culinary or storage pots to

nicely engraved bowls and red-surfaced or engraved bottles.

[12]

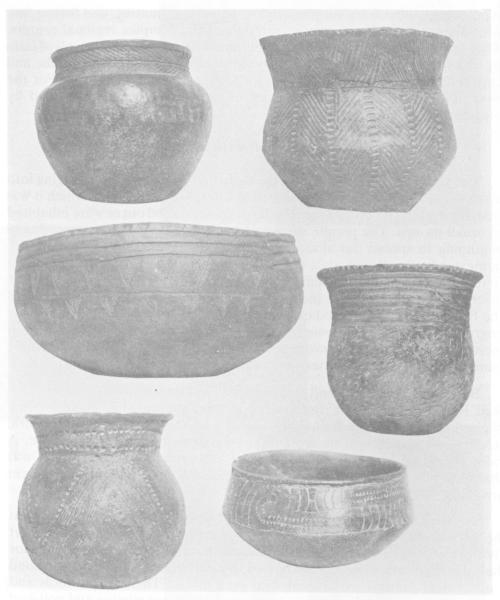

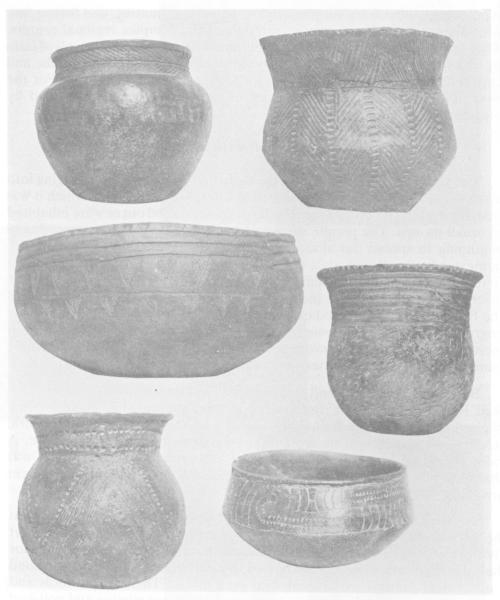

Bossier Focus pottery from Mill Creek site, Lake Bistineau. Photos courtesy of Sergeant O. H. Davis.

[13]

A Bossier group of higher culture lived along Willow Chute, an old Red

River channel in the valley east of Bossier City. Farming homesteads and

hamlets are strung along its course and two large mounds—Vanceville and

Werner—mark the Bossier ceremonial centers. Beneath the Werner mound,

destroyed in the 1930’s, were the ruins of an immense lodge which was

circular with a projecting entrance. The entire lodge measured eighty by

ninety feet. It was probably ceremonial, or the lodge of a Caddi (chief), as few

arrows, tools, or personal possessions were found. There were quantities of

deer and other animal bones, fish and turtle bones, and mussel shells. Broken

pottery in large amounts denoted feasts and the ceramics were of exceptional

quality. No burials or whole vessels were found.

Each lateral lake along Red River—Black Bayou, Caddo, Wallace, Clear,

and Smithport lakes on the west side; Bodcau, Bistineau, Swan, and Black

lakes on the east—has Bossier period sites around its margins. Occupations

continue westward to Sabine River and into eastern Texas, southward almost

to Catahoula Lake, eastward along D’Arbonne and Corney bayous toward

the Ouachita, and northward into Arkansas. Either late Bossier or Belcher

people could have been in the populous Naguatex district described by the

De Soto chroniclers, encountered just before the Spaniards crossed Red

River.

BELCHER FOCUS

The Belcher mound site, in Red River Valley about twenty miles north of

Shreveport, gives its name to this Caddo culture period. Radiocarbon dates at

the site and comparisons with other cultures suggest that the Belcher Focus

began about A.D. 1400 and lasted into the 17th century. During its beginning.

Belcher culture probably overlapped and coexisted with Bossier culture.

The Belcher site was excavated by Webb (1959) and his associates over a

ten year period. The Belcher mound contained a succession of levels on

which houses were built, burned or deserted, and covered over with new

buildings. Burials were placed in pits beneath the house floors or through the

ruins of burned houses. It is inferred that the houses were ceremonial lodges

or chiefs’ houses. The earliest house was rectangular, with wall posts erected

in trenches and packed with clay; a seven-foot entranceway projected northeastward.

The walls were clay-daubed, and the gabled roof covered with

grass thatch. Later houses were circular, also with projecting entranceways,

and with interior roof supports and central hearths. They also were daubed

and thatch-covered, but were divided into compartments, which contained

internal posts for seats or couches and sometimes small hearths for each[14]

compartment. Food remains found on the floors of Belcher houses included

maize, beans, hickory nuts, persimmon seeds, pecans, mussel and snail shells,

and bones of deer, rabbit, squirrel, fox, mink, birds, fish (gar, catfish, buffalo,

sheepshead, and bowfin), and turtle. Belcher tools encompassed stone celts

(hatchets or chisels), arrow points which had tiny pointed stems, flint scrapers

and gravers, sandstone hones, bone awls, needles and Chisels, shell hoes,

spoons and saws, and pottery spindle weights.

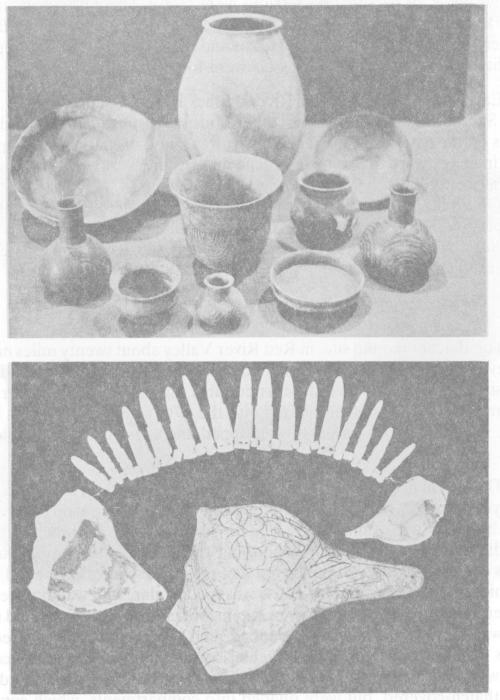

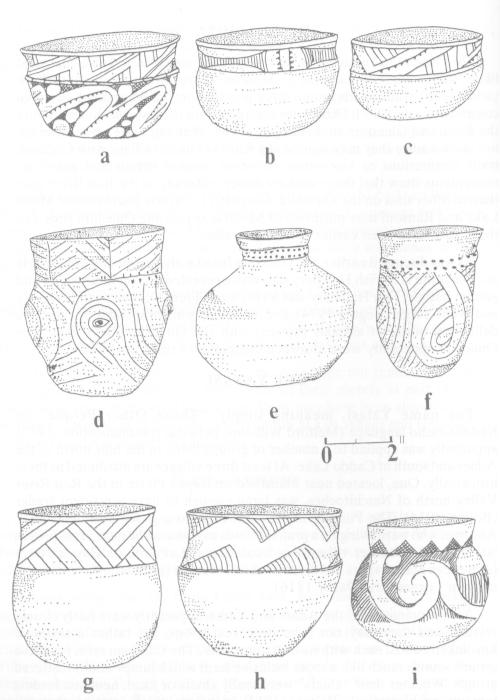

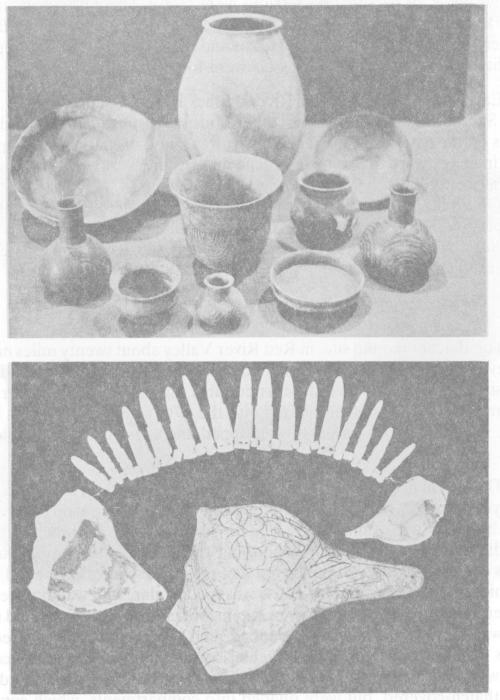

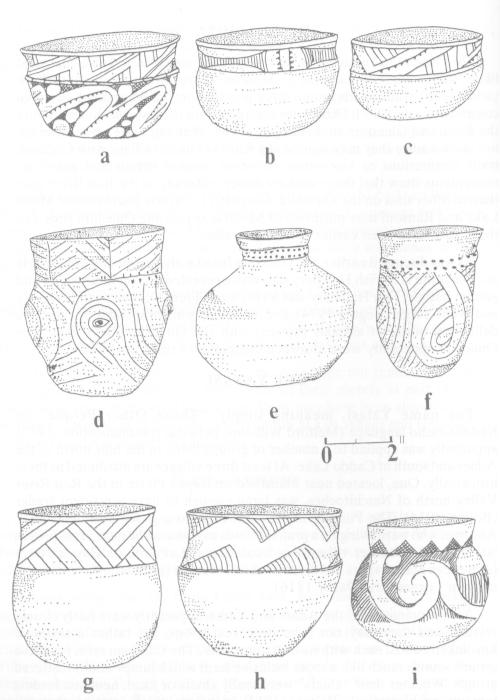

Prehistoric Caddo pottery, conch shell ceremonial drinking cups, and lizard effigy shell necklace from

Belcher Mound, Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Artifacts date approximately A.D. 1300 to 1400.

[15]

Ornaments found with burials or on house floors at Belcher include

beads, anklets, pendants and gorgets of shell, pearls, ear ornaments of shell,

bone and pottery, bone hairpins, bear tooth pendants, shell inlays, and small

shell bangles. Some of the shell pendants were carved in lizard or salamander

effigy forms. Ceremonial drinking cups made of conch shells were sometimes

decorated, one bearing a composite flying serpent-eagle design. Platform and

elbow pipes were of baked clay. Split cane basketry or matting fragments

show herringbone or 1-over-4-under weave.

Belcher pottery was superior to that of the Bossier people and, indeed, is

some of the best in the entire Caddoan area. There was a diversity of bowl,

bottle, urn, jar, vase, miniature, and compound forms. Large storage ollas

were found broken on house floors. Techniques of decoration involved

engraving, stamping, incising, trailing, ridging, punctating, brushing,

applique nodes, insertion of red or white pigment into designs, red slipping,

polishing, pedestal elevation, rattle bowls, bird and turtle effigies, and tripod

and tetrapod legs. Many of the vessels had ornate or intricate curvilinear

designs, with scrolls, circles, meanders, spirals, and guilloches; sun symbols,

crosses, swastikas, and triskeles were added.

Many of the twenty-six burials found in Belcher mound exhibited a

carry-over of the early Caddo burial ceremonialism, presumably including

human sacrifice. Individuals or groups of up to seven persons were placed in

shaft burial pits, and often were surrounded by many pottery vessels—sometimes

in stacks—in addition to tools, arrows, ornaments, food offerings,

vessels with spoons, decorated drinking cups, pipes, and other indicators of

high rank. As many as twenty to forty pottery vessels had been placed in a

single pit. Even small children had ornaments and numerous vessels, as

though they were of the nobility. This suggests a hereditary social ranking as

was found among the Natchez Indians.

Other mound centers of Belcher culture, occurring along Red River into

southwestern Arkansas, show similar ceremonialism. Villages and hamlets

along the river to Natchitoches and into the uplands are marked by typical

Belcher pottery sherds. In all, late Belcher people were dispersed widely, and

their way of life gave rise to the generalized cultural base that existed at the

time of European intrusion.

THE HISTORIC CADDO

If one views the Caddoan archaeological sequence as a tree trunk, identifiable

branches seem to begin spreading by about A.D. 1450 (Belcher

Focus). After that point, several distinct tribal branches can be recognized,[16]

each with its own particular language, or dialect, and customs. Within relatively

short distances these groups often exhibited striking differences.

The Louisiana Caddoan-speaking groups were the Adaes, Doustioni,

Natchitoches, Ouachita and Yatasi. These groups seem to have been concentrated

around Natchitoches, Mansfield, Monroe, and Robeline, Louisiana.

Their total aboriginal territory stretched from the Ouachita River west to the

Sabine River and south to the mouth of Cane River.

On Red River, in northeastern Texas and southwestern Arkansas, there

were other Caddoan groups: Kadohadacho, Petit Caddo, Nasoni, Nanatsoho,

and Upper Natchitoches. Eventually, due to pressure from the Osage,

these groups migrated south to Louisiana and settled north of the Yatasi,

near Caddo Prairie and Caddo Lake.

The Caddoan tribes seem to have had strong cultural affiliations. In fact,

some anthropologists have considered them part of three vast inter-tribal

confederacies (Swanton 1942; Hodge 1907). In eastern Texas another

group, led by the Hasinai, consisted of the Ais, Anadarko, Hainai, Hasinai,

Nabiti, Nacogdoches, and Nabedache. This group also has been considered a

large confederacy (Hodge 1907).

The various peoples mentioned above seem to have been regional groups,

fairly fluid in nature, but tied to general geographic boundaries. Linguistic

differences served to differentiate them (Taylor 1963:51-59) and some, like

the Adaes, could hardly be understood by the others. However, the

Kadohadacho language dominated in the east—where nearly everyone understood

it—and the Hasinai language in the west.

These groups had chiefs, or Caddi. Generally one man had more prestige

than any other Caddi, but multiple chiefs—usually two—were present in

most communities. Other groups seem to have had tama (local organizers),

but chiefs were weak or lacking. Polity, then, consisted of the Caddi, or chiefs,

and tama, a sort of organizational leader (often confused with the chief by

early Europeans) who was powerful enough to gather the people for work,

war, or ceremonials. The Caddi were a select group—likely the historic

equivalent to the priest-chiefs of prehistoric times. Priests and witches composed

a non-secular leadership among the Caddoan groups, but by historic

times they had become somewhat separate from the warrior-chiefs who led

the tribes.

It can be seen, then, that the Caddoan peoples had several of the criteria

of true chiefdoms (Service 1962): territory, leadership, and linguistic-cultural

distinctiveness. All of the Europeans—French, Spanish and[17]

Anglo-American—who dealt with them left records relative to their character

and intelligence. As late as the 19th century the Caddo still boasted that

they had never shed white blood (Swanton 1942) and their chiefs still were

respected.

In the age of tribal self-determination and Indian sovereignty, it seems in

order to explain basic Caddo tribalism. Contrary to many other southeastern

Indian groups, the Caddoan people seem to have clung tenaciously to land

and leadership even after the erosive effects of European contact. The fact

that their roots extended into prehistory gave them strength and self-confidence.

They kept their faith and polity, and their traditions remain even

today.

EUROPEAN CONTACT

The earliest contacts with Europeans in Louisiana were fleeting. The best

accounts were left by Henri de Tonti who reached a Natchitoches village in

February of 1690. He was searching for the lost La Salle expedition and went

on to visit the Yatasi, Kadohadacho, and Nacogdoches (Williams 1964). No

other visits seem to be recorded for the next decade, even though Spanish

efforts to Christianize the East Texas Caddo intensified. Contact is indicated

by the 1690’s in such practices as the tribes holding Spanish-style horse fairs

(Gregory 1974).

St. Denis and the Natchitoches Indians, 1714. Mural in Louisiana State Exhibit Museum, Shreveport.

[18]

In 1701 Governor Bienville and Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, guided by

the Tunica chief, Bride les Boeufs or Buffalo Tamer, arrived at the Natchitoches

area. They visited the Doustioni, Natchitoches, and Yatasi villages,

and then returned to New Orleans. Bienville was especially desirous of

contacting the Kadohadacho to the north (Williams 1964; Rowland and

Sanders 1929). This trip, ostensibly for exploration, was probably an attempt

to obtain two commodities the French in lower Louisiana were desperate for:

livestock and salt (Gregory 1974). The Tunica had long engaged in the

Caddoan salt, and later, horse trades (Brain 1977), and like them, the

Natchitoches quickly began capitalizing on their French connection. The

Natchitoches employed an old Caddoan trade strategy, that of moving to the

edge of another tribe’s territory, in order to be near their customers, and later

returning to their own territory. Accordingly, the Natchitoches claimed a

crop failure and relocated to the vicinity of Lake Pontchartrain, to trade with

the French. Eventually, in 1714, they returned to Red River with St. Denis

(McWilliams 1953). Likewise, the Ouachita had just moved back from the

Ouachita River where they had relocated in order to trade with Tunican

speakers (Gregory 1974).

After St. Denis returned to Red River in 1714, the Caddoan people in

Louisiana were to be impacted constantly by European migrants. Indian

polity and territory were eroded severely by more European settlements and

the depredations of displaced populations of other Indian tribes like the

Choctaw, Quapaw, and Osage.

Fort St. Jean Baptiste aux Natchitos was founded in 1714; it was the

earliest European settlement in northwestern Louisiana. The East Texas

missions, started in 1690, had not introduced many non-Indians to that area.

The French settlements were different, however, and the Caddoan people

began to see a gradual augmentation of European population. The French

had, in general, good relations with the Caddo and by the 1720’s a number of

them had Caddoan kinsmen.

In 1723, to counter French attempts at establishing a western trade, the

Spanish established an outpost, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes

(Bolton 1914). The Spanish presidio, or fort, became a hub for clandestine

traders—French, Indian and Spanish—and lasted for some fifty years (Gregory

1974). Horses, cattle, and Lipan Apache (Connechi) slaves were traded

via Los Adaes, and by the mid-eighteenth century the Spanish governors had

named the site the capital of Spanish Texas.

The Caddo—Adaes, Natchitoches, Ouachita, Doustioni, and all the

others—were caught between the political and economic machinations of the

European powers. Gradually, the seesaw of European boundaries crossed[19]

what the Caddo all knew as their tribal territories. Traders resided in their

larger communities, and seasonal hunts to the west tied them to the mercantile

policies of the French and Spanish. After Louisiana was ceded to Spain at

the end of the French and Indian War, French traders were left in charge of

most Indian affairs in Louisiana because of the quality of their relationship to

the Indians. For example, Athanase de Mézières (Bolton 1914), St. Denis’

son-in-law, became a power on the frontier because of his close relationship

to the Caddo.

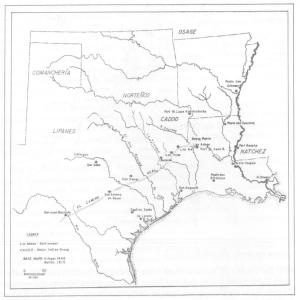

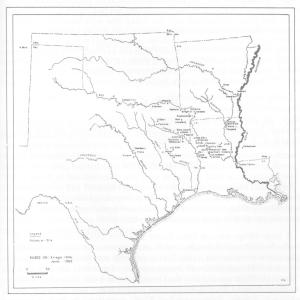

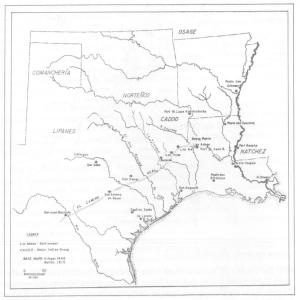

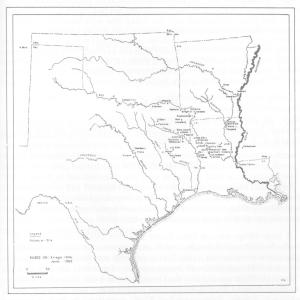

Caddoan interaction, 18th century A.D.

[20]

Caddoan-European ties remained close until 1803 when the Louisiana

Purchase brought Anglo-Americans into contact with the Caddoan groups.

The Anglo-Americans had new trade and military policies, and in spite of

their agreement to recognize all prior treaties between France, Spain, and

Indian tribes, they were not very careful to do this. The French and Spanish

had ratified land sales by tribes and had insisted that their citizens respect

Caddoan land and sovereignty, but the Americans saw new lands with few

settlements, and were quick to encourage white settlement. The old Caddo-French-Spanish

symbiosis was ending.

European settlements in Caddoan area, 18th century A.D.

The Caddoan-speaking groups began to move together by the late

eighteenth century. The Kadohadacho apparently absorbed several smaller

groups—Upper Natchitoches, Nanatsoho, and Nasoni—and shifted south.[21]

Osage raids had taken their toll and the Kadohadacho moved to Caddo

Prairie, farther from the plains, on marginal land (Swanton 1942). They

settled on the hills to the southwest of the prairie (Soda Lake) near modern

Caddo Station and added their numbers to the other Red River tribes in

Louisiana.

Beset by many problems, the American agents at Natchitoches began

moving the agency about, trying to keep the Caddo away from white settlements.

It was moved to Grand Ecore, Sulphur Fork, Caddo Prairie, and

finally to Bayou Pierre about six to seven miles south of Shreveport (Williams

1964).

The Louisiana Caddoans also found themselves estranged from their

cultural kinsmen in eastern Texas. First, the East Texas tribes remained

under Spanish domination while their neighbors were American. Policies in

Texas were quite different until the Texas Revolution and the foundation of

the Republic in the 1830’s and 1840’s. The new Texicans refused to allow old

patterns of trade and traverse for fear of having to deal with even larger

Indian populations.

The Caddoan tribes were consolidated enough by 1834 that the American

agents had begun to treat them as though they were a single group. The

term Caddo, an abbreviated cover term for Kadohadacho, one of the larger

groups, began to cover all the tribes in the American Period. It was this

amalgam of tribal units with which the United States decided to deal.

Caddo Indian Treaty of Cession, July 1, 1835. Mural in Louisiana State Exhibit Museum, Shreveport.

[22]

On June 25-26, 1835, some 489 Caddo gathered at the Caddo Agency

seven or eight miles south of Shreveport on Bayou Pierre and on July 1, 1835,

they agreed to sell to the United States approximately one million acres of

land in the area above Texarkana, Arkansas, south to De Soto Parish,

Louisiana (Swanton 1942). Two chiefs, Tarsher (Wolf) and Tsauninot, were

the leaders of the Caddoan groups present at the land cession.

Present also at the land cession was their interpreter, Larkin Edwards, a

man they regarded so highly that they reserved him a sizable piece of land

(McClure and Howe 1937; Swanton 1942). Further, the treaty reserved a

sizable block of land for the mixed Caddo-French Grappe family. Descended

from a Kadohadacho woman and a French settler, François Grappe had

served his people well. His efforts to protect not only the Caddo, but also the

Bidai and others in East Texas, from American traders had resulted in his

termination as chief interpreter for the American agents. The Caddoan

people continued to respect and honor him.

The Caddo were to be paid $80,000, of which $30,000 was in goods

delivered at the signing, and the remainder in annual $10,000 installments

for another five years. Immediately Tarsher led his people into Texas and

settled on the Brazos River, much to the chagrin of Texas authorities (Gullick

1921). Another group, led by Chief Cissany, stayed in Louisiana. They lived

near Caddo Station in 1842 (seven years after the land cession). Texicans

actually invaded the United States to insist that the Caddos disarm, the rumor

in Texas being that the American agent had armed the Caddo and made

incendiary remarks regarding the new Republic. The Louisiana chiefs offered

to go to Nacogdoches as hostages to show their good faith, but the

Texicans refused them on the grounds it might mean recognition of Caddoan

land rights and polity in Texas (Gullick 1921).

Eventually these Louisiana Caddo left—their credit was cut off by local

merchants, their payments ended, and the United States protection was

failing—and headed for the Kiamichi River country in Oklahoma. The

Caddoan presence in Louisiana, after a millennium, or more, was over.

CADDOAN TRIBAL LOCATIONS AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN LOUISIANA

One of the most difficult problems in American archaeology is the firm

connection of historic tribal locations to specific material remains and sites.

In recent years a number of efforts (Wyckoff 1974; Tanner 1974; Williams

1964; Gregory and Webb 1965; Neuman 1974) have dealt with this topic for

the Louisiana Caddoan groups.

[23]

Again, the term Caddo has no real meaning. Each of the groups had its

own political existence, and both the Spanish and French realized that. Their

approach to Indian affairs has left us much better information than that of the

Americans. John Sibley, the first American agent, with the aid of the half-Caddo,

François Grappe, gave us good information, but through time the

American policy increasingly obscured tribal groups. By the time of the 1835

land cession the Americans were talking merely of the Caddo Nation. In the

1835 Treaty not a single warrior was identified by tribe, nor were the chiefs

(Swanton 1942); this was a purely political machination by the Americans.

Caddoan and adjacent Indian groups about A.D. 1700.

Since the early American policy has obscured the tribal diversity and

history of the Caddoan groups in Louisiana, it seems in order to return to the

older practice of recognizing the individual groups. Each will be discussed[24]

briefly, in turn, and archaeological sites will be related where possible. As was

the practice in French and Spanish days, the tribes will be discussed from

southernmost to northernmost, as they would be encountered as one

ascended the Red River.

THE NATCHITOCHES

The Natchitoches, or “Place of the Paw-Paw” (all translations by Melford

Williams, personal communication, 1973), sometimes simply stated as the

“Paw-Paw People,” were the southernmost Caddoan group. They had absorbed

the Ouachita (“Cow River People”) by 1690 (Gregory 1974) and will

be treated as a single group here.

The Natchitoches lived in a series of small hamlets, each with its own

cemetery and corn fields. One hamlet had a temple which was described by

Tonti (Walker 1935) and their whole settlement stretched from about Bermuda,

Louisiana, to the vicinity of Natchitoches. Throughout their early

history they remained in the alluvial valley of the Red River where only a few

areas, usually “islands” of older terraces, were above the active floodplain.

Wyckoff (1974) has stated that they preferred the tupelo gum-bald cypress

biotic zone along the Red River, but in reality they seem to have lived on the

mixed hardwood, cane-covered natural levees or in the oak-hickory ecological

communities found on higher ground.

Natchitoches chiefs’ names are scarce, and one gets the impression that

their chiefs were not very powerful. However, St. Denis seems to have

purchased property from a chief called the White Chief. It can be assumed

that the tribes all had Caddi, tama and priests. However, it seems that there

were more egalitarian structures among the Natchitoches, Adaes, and Yatasi

than in the East Texas or Great Bend groups.

Documents indicate that at least four sites were occupied by the Natchitoches

between 1690 and 1803: White Chief’s village, Captain’s village

(Pintado Papers), La Pinière village (Bridges and Deville 1967:239), and Lac

des Muire village (Sibley 1832; Abel 1933). There are a larger number of

archaeological sites which have yielded Natchitoches Engraved, Keno

Trailed, or Emory Incised ceramic vessels or sherds, catlinite pipes, glass

trade beads, copper or brass objects, knives, and gun parts. These include the

U. S. Fish Hatchery (Walker 1935), the Lawton (Webb 1945), the Southern

Compress (Gregory and Webb 1965), Natchitoches Country Club, Chamard

House, American Cemetery, Settle’s Camp, and Kenny Place sites (Gregory

1974).

[25]

The Southern Compress and American Cemetery sites seem to correspond

to White Chief’s villages. The Fish Hatchery and Kenny Place sites are

likely combinations of Ouachita and Natchitoches groups visited by Tonti

and others. Settle’s Camp site and Country Club site are along the high hills

west of the modern town of Natchitoches and may well be the dispersed

settlement known as La Pinière (Pine Woods) to the French. Chamard House

site may have belonged to the French trader Chamard, or possibly one of the

Grappes; located on the bluff overlooking the active Red River, it remains

undocumented.

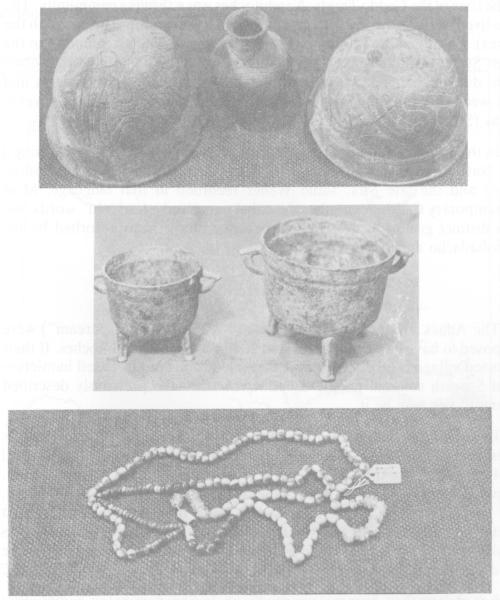

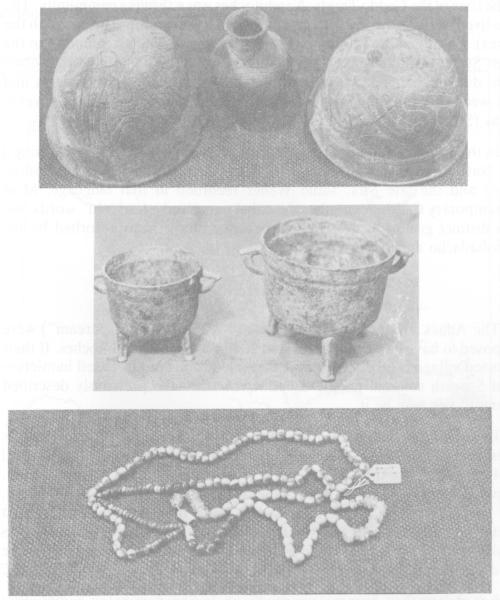

Historic Natchitoches pottery, French iron tripod pots, and Venetian glass trade beads. These 18th

century A.D. artifacts were found at the Southern Compress and Lawton sites.

[26]

The Lawton site was the site seized for debts from the son of the Christian

Indian, known as Pierre Captain, probably a sub-chief or possibly a tama, of

the Natchitoches (Pintado Papers: 139). The latest Natchitoches village, Lac

des Muire, was north of Powhatan and on the west bank of the Red River.

Sibley (1922) pointed out that although the tribe was reduced in number they

retained their language and distinctive dress. They were farmers and lived in

houses, presumably their traditional wattle-daub constructions.

Natchitoches land was gradually surrounded by Anglo-Americans and,

by the time of the Caddo Treaty, Natchitoches was a thriving community. The

tribe lived north of the town, near the Grappes (their cultural broker with the

whites). Local tradition holds that they were loaded on a steamboat on the

Front Street dock and taken to Oklahoma in 1835—something that obviously

did not happen. In 1843 the tribe was still together under Chief

Cho-wee (The Bow) and living near the Kadohadacho on the Trinity River in

Texas (Swanton 1942:96).

In the 1960’s Caddos living near Anadarko, Oklahoma, still could sing a

few Natchitoches songs (Claude Medford, Jr., personal communication,

1975) and the late Mrs. Sadie Weller recorded in that language. Most

contemporary Caddo remember the tribal name and a few “old” words, but

as a distinct group the Natchitoches seem to have been absorbed by the

Kadohadacho and Hasinai.

THE ADAES

The Adaes (from Na·dai which meant “A Place Along a Stream”) were

supposed to have had a village on Red River, near the Natchitoches. If their

reported village is taken to mean a dispersed series of kin-based hamlets—what

Spanish colonial people called rancherías—the previously described

Chamard site may be it.

In the 1720’s the Spanish established a mission for the Adaes, but its

priest and one lay-soldier were expelled by the French lieutenant, Blondel

(Bolton 1921). At the time there were no Indians living at the mission.

Apparently, they relocated nearer the Spanish, but conversions were rare,

and the Adaes were more interested in trade than religion. So, for that

matter, were the Spanish, and when the presidio (now called Los Adaes) was

established in 1723, ostensibly to protect the mission, the Adaes seem to have

lived all around the vicinity.

Los Adaes then became essentially an Indian dominated community:

Lipan, Coahuiltecans, Adaes, Wichita, Tawakoni, and others lived there off[27]

and on. Even the commandant, Gil Ybarbo, was married to a mestiza, a

half-Indian woman. Whenever the Spanish authorities in Texas needed

translators for Caddoan languages, they sent for soldiers from Los Adaes

(Blake Papers).

There was an Adaes village near Big Hill Firetower at a place called La

Gran Montaña (Bolton 1962) which has never been found, and another

nineteenth century village on Lac Macdon. The latter is probably a later

village than the one known on Spanish Lake where burials with European

goods were excavated by James A. Ford (1936, unpublished fieldnotes,

Museum of Geoscience, Louisiana State University).

Historic archaeological sites in the Caddoan area.

[28]

Taylor (1963:51-59) finally placed Adaes as a definite Caddoan language,

but it was the most deviant of all (Sibley 1832), and the Adaes became

more and more western in their cultural orientation (Gregory 1974). They

gradually extended to the Sabine River where a late trash pit (A.D. 1740) at

Coral Snake Mound may be evidence of their presence (McClurkan, Field

and Woodall 1966). It contained glass trade beads, and a French musket lock

was found nearby. Their Lac Macdon village, where they remained as late as

1820, was probably near the water body known today as Berry Brake and

may well be on Allen Plantation.

Little is known of Adaes history or culture. De Mézières (Bolton

1914:173) noted that they were severely impacted by Europeans and “extremely

given to the vice of drunkenness.” Like the Natchitoches, they seem

to have had close relationships with the Yatasi who were sometimes called

the Nadas, likely a homonym for Na·dais.

One Adaes chief who was their leader in the 1770’s has been identified

and they are clearly an archaeologically distinct group. Gregory (1974) has

pointed out the higher frequencies of bone-tempered pottery and the ceramic

types Patton Engraved and Emory Incised from trash pits at Los Adaes.

Unlike the Natchitoches and others, the Adaes are not remembered by

contemporary Caddo who may have heard of them merely as part of the

Yatasi, who are remembered as a group. Many may have been absorbed, as

Christians, into the general mestizo population at Los Adaes and still have

descendants in northwestern Louisiana.

THE DOUSTIONI

Swanton (1942) translates Doustioni as “Salt People,” and they seem to

have lived near the salines northeast of Natchitoches. Little else is known

about them, and they do not seem to persist into the nineteenth century. They

either disappeared or mingled with the Natchitoches.

A large village site, on Little Cedar Lick, has yielded shell-tempered

sherds, Venetian glass beads, and French faience, all early to middle

eighteenth century artifact types. The site probably was the major Doustioni

settlement. Other evidence of late occupations appears at Drake’s Lick.

Williams (1964) points out that the Doustioni once had a village below the

Natchitoches, and, though it has not been located, it may have been near the

confluence of Saline Bayou and Red River, somewhere below Clarence,

Louisiana. Saline Bayou provides easy access to the salt licks and was described

by several early travelers (Le Page du Pratz 1774).

The Ouachita were living on the river of that name before 1690. The most

likely site is Pargoud Landing at Monroe where recent excavations have

yielded early trade beads but no other goods (Lorraine Heartfield, personal

communication, 1977). Other sites considered for the historic Ouachita were

the Keno and Glendora sites (Gregory 1974; Williams 1964), but these are

not certain since they may represent a Koroa (Tunica) village with Caddoan

trade connections or vice-versa. However, animal burials and grave arrangements

show that these sites are closer culturally to the Red River sites

than to other sites on the Ouachita. Gregory (1974) has discussed the Moon

Lake and Ransom sites northeast of Monroe as possible Ouachita sites, but

these may have been earlier Koroa sites also.

As was discussed earlier, the Ouachita fused with the Natchitoches, likely

at or near the U.S. Fish Hatchery site, which revealed their ceramic styles and

animal burials. Fish Hatchery was a very early French contact site (Gregory

and Webb 1965; Gregory 1974), and it is the only historic Caddo site to share

deliberate burial of animals (horses) with the Ouachita River sites. The

Ouachita apparently were absorbed completely before the 1720’s.

THE YATASI

The name Yatasi, meaning simply “Those Other People” in

Kadohadacho language (Melford Williams, personal communication, 1977)

apparently was applied to a number of groups living in the hills north of the

Adaes and south of Caddo Lake. At least three villages are attributed to them

historically. One, located near Mansfield on Bayou Pierre in the Red River

Valley north of Natchitoches, was large enough to have a resident trader

(Bolton 1914). The Pintado Papers also refer to a group and their chief,

Antoine, who were living on a prairie known as Nabutscahe near Mansfield as

late as 1784. Another village was located near LaPointe on Bayou Pierre

(American State Papers 1859), and a third was near the Sabine River close to

modern Logansport (Darby 1816).

As was pointed out, the Adaes and Yatasi apparently were fairly closely

related, and they may not have been real tribes, but rather a series of

kin-linked bands, each with its own autonomy. The Caddoan term for these

groups sounds much like a more inclusive term which lumps small, scattered

groups. Whether their “chiefs” were really chiefs or local, heuristic leaders

remains problematical. Bolton (1914) mentions chiefs, stating that the

Athanase de Mézières gave peace medals to two chiefs, Cocay and Gunkan,

in 1768.

[30]

Historic 18th century A.D. Caddoan pottery vessels from Los Adaes, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana.

[31]

Presently, the archaeological picture seems to support the hypothesis that

the Yatasi included a number of small autonomous bands. A cluster of sites is

located around Chamard Lake: the Arnold or Bead Hill site (Gregory and

Webb 1965), the Wilkinson site (Ford 1936), and the Eagle Brake site

(Gregory 1974). These sites have fairly large, deep middens and all have

yielded Natchitoches Engraved sherds and trade goods. This is somewhat

different from the scattered shallow sites nearer Natchitoches and suggests

more clustered populations, but still a dispersed settlement pattern. None of

these archaeological sites seems to correspond to the Red River-Bayou

Pierre sites, though they shared the drainage. Although it is known that the

Lafittes, Poisot, and Rambin claims were near the Yatasi villages, and all of

these settlers traded with the tribe (Pintado Papers:82-84), their

documented sites remain to be found.

Contemporary Caddo, most of whom are Kadohadacho or Hasinai, frequently

mention the Yatasi when asked about other groups and know they

once existed. However, it remains obscure whether the Yatasi were one or

many little groups. They seem to have been absorbed by the Kadohadacho,

but it is hard to trace them after the American land sales.

THE KADOHADACHO

The Kadohadacho (“Great Chiefs” in the Caddoan languages) were the

dominant Caddoan-speaking group in the Red River Valley. They occupied a

widely dispersed settlement with a temple and a mound, in northeastern

Texas and probably near the Great Bend at Texarkana. The Petit Caddo,

Nasoni, Nanatsoho, and Upper Natchitoches were absorbed by the

Kadohadacho, and the tribes abandoned their Great Bend villages (at least

four archaeological sites there seem related to these groups) and shifted

south to Caddo Lake. Once there, their chief, Tinhiouen, dealt politically

with both the Spanish (Bolton 1914) and the Americans.

The Kadohadacho language was the most widely understood of all the

Caddoan tongues, and, according to early accounts (Sibley 1922), the tribe

was the most influential of all the Caddos. They had a sort of warrior class

comparable to the “Knights of Malta.” It is, therefore, not surprising that the

Kadohadacho became the Caddo Nation of the American Period (Williams

1964).

The Kadohadacho settled, at least by 1797 (Swanton 1942), at a location

known as Timber Hill (Mooney 1896:323) near Caddo Lake (Swanton

1942). Williams (1964) has pointed out that this village has never been[32]

located archaeologically. However, it should be noted that the Texicans

placed the tribe near Caddo Station in 1842 (Gullick 1921).

Immediately after the American land treaty, the tribe apparently split

into factions. A group under Tarsher moved to the Brazos River in Texas; the

others stayed in Louisiana until at least 1842, when they apparently moved to

live with the Choctaw some time that year (Swanton 1942:95).

The late Miss Caroline Dormon (1935, unpublished field notes, Special

Collections, Eugene Watson Library, Northwestern State University) recorded

a single burial, with a “silver crown, copper, etc.,” which was found

near Stormy Point on Ferry Lake by James Shenich, son-in-law of Larkin

Edwards. This burial may have been very near the Kadohadacho village.

According to the Dormon notes, this was a favorite crossing to Shreveport

and the Indian trace was visible as late as the 1860’s. In spite of the fact that

“Glendora Focus” artifacts were not present (Williams 1964), it can no

longer be said that there were no historic Caddoan sites in the Treaty Cession

areas of De Soto and Caddo parishes. In fact there is a good possibility that

this was the grave of the powerful chief, Dahaut, who died in 1833 (Caddo

Agency Letters).

CADDOAN HERITAGE

The Caddo left their names, art, and culture in Louisiana. A number of

colonial European families can boast of Caddoan ancestors: Grappes, Brevelles,

Balthazars, and others. In Oklahoma, after years of wandering, the

Kadohadacho and Hasinai have become the dominant groups. Yet, as has

been pointed out, old traditions persist. People still recall stories of floods on

Caddo Prairie which left cows hanging by their horns in the trees, and know

that Natchitoches meant the place of “little yellow fruits” that do not grow in

Oklahoma.

At Binger and near Hinton, Oklahoma, the old songs and dances continue

to be heard and seen. The Turkey Dance still is held before the sun sets,

and individuals sing the “Dawn Song” or “Tom Cat Song” on their way home

from the dancing.

The Caddo now visit Louisiana, especially Natchitoches and Shreveport,

to see the places of their tradition. Places are part of Indian tradition and[33]

pilgrimages are sacred acts. Perhaps now other Louisianians will join the

Caddo who realize how much Indian culture remains in northwestern

Louisiana.

[34]

American State Papers

1859 Documents of the Congress of the United States in Relation to the

Public Lands, Class VIII, Public Lands, Vol. 3, Washington.

Blake Papers

1939 Translations of the Spanish Records of Nacogdoches County,

Texas. Manuscript. Special Collections Library, Stephen F. Austin

University, Nacogdoches.

Bolton, Herbert E.

1914 Athanase de Mézières and the Louisiana-Texas Frontier, 1768-1780.

Arthur H. Clark, Cleveland.

1921 The Spanish Borderlands. Yale University Press, New Haven.

1962 Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century. Russell and Russell, New

York.

Brain, Jeffrey P.

1977 On the Tunica Trail. Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities

Commission, Anthropological Study No. 1, Baton Rouge.

Bridges, Catherine and Winston Deville

1967 Natchitoches and the Trail to the Rio Grande: Two Eighteenth

Century Accounts by the Sieur Derbanne. Louisiana History,

Vol. 8, pp. 239-247.

Caddo Agency Letters

1819-1835 Correspondence of George Gray and Jehiel Brooks. Microfilm.

National Archives, Washington.

Darby, William

1816 A Geographical Description of the State of Louisiana. John

Melish, Philadelphia.

[36]

Ford, James A.

1936 Analysis of Indian Village Site Collections from Louisiana and

Mississippi. Department of Conservation, Louisiana Geological

Survey, Anthropological Study No. 2.

Fulton, Robert L. and Clarence H. Webb

1953 The Bellevue Mound: A Pre-Caddoan Site in Bossier Parish,

Louisiana. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, Vol. 24,

pp. 18-42.

Gagliano, Sherwood M. and Hiram F. Gregory, Jr.

1966 A Preliminary Survey of Paleo-Indian Points from Louisiana.

Louisiana Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 62-77.

Gregory, Hiram F., Jr.

1974 Eighteenth Century Caddoan Archaeology: A Study in Models

and Interpretation. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Department of

Anthropology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

Gregory, Hiram F., Jr. and Clarence H. Webb

1965 European Trade Beads from Six Sites in Natchitoches Parish,

Louisiana. Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 18, No. 3, Part 2, pp.

15-44.

Gullick, Charles Adams (Editor)

1921 Papers of Mirabeau Lamar, 6 Vols. A. C. Baldwin and Sons,

Austin.

Hodge, Frederick Webb (Editor)

1907 “Caddo.” Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico.

Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 30, Part 1, Washington.

La Page du Pratz, Antoine Simon

1774 The History of Louisiana. English translation published by T.

Becket, London. (Original: Histoire de la Louisiane, Paris 1758).

McClure, Lilla and J. Ed Howe

1937 History of Shreveport and Shreveport Builders. J. Ed Howe,

Shreveport.

[37]

McClurkan, Burney B., William T. Field and J. Ned Woodall

1966 Excavations in Toledo Bend Reservoir, 1964-65. Papers of the

Texas Archaeological Salvage Project, No. 8, Austin.

McWilliams, Richebourg G. (Editor)

1953 Fleur de Lys and Calumet: Being the Pénicaut Narrative of French

Adventure in Louisiana. Louisiana State University Press, Baton

Rouge.

Mooney, James

1896 The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. 14th

Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1892-1893,

Part 2, pp. 322-324, Washington.

Moore, Clarence B.

1912 Some Aboriginal Sites on Red River. Journal of the Academy of

Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 14, pp. 482-644.

Neuman, Robert W.

1974 Historic Locations of Certain Caddoan Tribes. In Caddoan Indians

II, pp. 9-147. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

Pintado Papers

n.d. Land Claim Documents, State of Louisiana. Manuscript. Louisiana

State Land Office, Baton Rouge.

Rowland, Dunbar and Albert S. Sanders

1929 Mississippi Provincial Archives, 1701-1729. Mississippi Department

of Archives and History, Jackson.

Service, Elman

1962 Primitive Social Organization. Random House, New York.

Sibley, John

1832 Historical Sketches of the Several Indian Tribes in Louisiana,

South of the Arkansas River, and Between the Mississippi and

Rio Grande. American State Papers, Class II, Indian Affairs, Vol.

1, pp. 721-731, Washington.

[38]

1922 A Report from Natchitoches in 1807. Edited by Annie Heloise

Abel. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, Indian

Notes and Monographs, Miscellaneous Series, No. 25, pp. 5-102.

Swanton, John R.

1942 Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo

Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 132,

Washington.

Tanner, Helen Hornbeck

1974 The Territory of the Caddo Tribe of Oklahoma. In Caddoan

Indians IV, pp. 1-67. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

Taylor, Allen R.

1963 The Classification of the Caddoan Languages. Proceedings of the

American Philosophical Society, Vol. 107, No. 1, pp. 51-59.

Thomas, Prentice Marquet, Jr., L. Janice Campbell and Steven R. Ahler

1977 The Hanna Site: An Alto Village in Red River Parish. New World

Research, Report of Investigations No. 3. Unpublished Manuscript,

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans.

Walker, Winslow M.

1935 A Caddo Burial Site at Natchitoches, Louisiana. Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 94, No. 14, Washington.

Webb, Clarence H.

1945 A Second Historic Caddo Site at Natchitoches, Louisiana. Bulletin

of the Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society, Vol.

16, pp. 52-83.

1946 Two Unusual Types of Chipped Stone Artifacts from Northwest

Louisiana. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological and Paleontological

Society, Vol. 17, pp. 9-17.

1948a Caddoan Prehistory: The Bossier Focus. Bulletin of the Texas

Archeological and Paleontological Society, Vol. 18, pp. 100-143.

1948b Evidences of Pre-Pottery Cultures in Louisiana. American Antiquity,

Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 227-232.

[39]

1959 The Belcher Mound: A Stratified Caddoan Site in Caddo Parish,

Louisiana. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, No.

16.

1963 The Smithport Landing Site: An Alto Focus Component in De

Soto Parish, Louisiana. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society,

Vol. 34, pp. 143-187.

Webb, Clarence H. and Monroe Dodd

1939 Further Excavations of the Gahagan Mound: Connections with a

Florida Culture. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological and Paleontological

Society, Vol. 11, pp. 92-126.

Webb, Clarence H. and David R. Jeane

1977 The Springhill Airport Sites, J. C. Montgomery I (16 WE 32) and

II (16 WE 33). Newsletter of the Louisiana Archaeological Society,

Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 3-7.

Webb, Clarence H. and Ralph McKinney

1975 Mounds Plantation (16 CD 12). Caddo Parish, Louisiana.

Louisiana Archaeology, Vol. 2, pp. 39-127.

Webb, Clarence H., Joel L. Shiner and E. Wayne Roberts

1971 The John Pearce Site (16 CD 56): A San Patrice Site in Caddo

Parish, Louisiana. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society,

Vol. 42, pp. 1-49.

Williams, Stephen

1964 The Aboriginal Location of the Kadohadacho and Related

Tribes. In Explorations in Cultural Anthropology, edited by Ward

H. Goodenough, pp. 545-570. McGraw-Hill Book Company,

New York.

Wyckoff, Donald G.

1974 The Caddoan Cultural Area: An Archaeological Perspective. In

Caddoan Indians, I, pp. 6-16. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 67235 ***