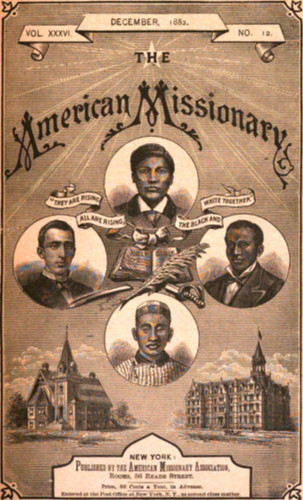

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The American Missionary -- Volume 36, No. 12, December, 1882, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The American Missionary -- Volume 36, No. 12, December, 1882 Author: Various Release Date: October 18, 2018 [EBook #58128] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN MISSIONARY, DECEMBER, 1882 *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, KarenD and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections)

DOUBLE NUMBER. SEE FOURTH PAGE COVER.

| Page. | |

| EDITORIALS. | |

| Paragraph—Financial Outlook. | 353 |

| Abstract of Proceedings at the Annual Meeting. | 354 |

| Summary of the Annual Report of The Treasurer. | 357 |

| General Survey. | 359 |

| FREEDMEN. | |

| Report of Committee on Educational Work. | 369 |

| Higher Education of the Negro. Pres. E. M. Cravath. | 370 |

| Report of Committee on Church Work. | 372 |

| Remarks of Rev. C. O. Brown. | 374 |

| AFRICA. | |

| Report of the Committee. | 375 |

| Report of the Committee on Proposed Exchange of Missions. | 376 |

| THE INDIANS. | |

| Report of the Committee. | 377 |

| Work and Duty in the East. Gen. S. C. Armstrong. | 378 |

| THE CHINESE. | |

| Report of the Committee. | 380 |

| Address of Rev. James Brand, D.D. | 381 |

| MISCELLANEOUS. | |

| Report of the Committee on Finance. | 383 |

| Petition of President Ware and Others. | 384 |

| Exchange of Missions. By Secretary Strieby. | 385 |

| ADDRESSES AT THE ANNUAL MEETING. | |

| President Hays’ Address. | 391 |

| Address of President A. D. White. | 395 |

| Address of Rev. A. G. Haygood, D.D. | 399 |

| From Address of Gen. C. B. Fisk. | 406 |

| From Address of Rev. A. J. F. Behrends. | 407 |

| Relation of the A. M. A. To Civilization, By Rev. F. L. Kenyon. | 409 |

| Dedication of Livingstone Missionary Hall. | 410 |

| Receipts. | 411 |

American Missionary Association,

56 READE STREET, NEW YORK.

President, Hon. WM. B. WASHBURN, Mass.

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY.

Rev. M. E. STRIEBY. D.D., 56 Reade Street, N.Y.

TREASURER.

H. W. HUBBARD, Esq., 56 Reade Street, N.Y.

DISTRICT SECRETARIES.

Rev. C. L. Woodworth, Boston. Rev. G. D. Pike, D.D., New York.

Rev. James Powell, Chicago.

COMMUNICATIONS

relating To the work of the Association may be addressed to the Corresponding Secretary; those Relating To the collecting fields, to the District Secretaries; letters for the Editor of the “American Missionary,” to Rev. G. D. Pike, D.D., at the New York Office.

DONATIONS AND SUBSCRIPTIONS

may be sent to H. W. Hubbard, Treasurer, 56 Reade Street, New York, or, when more convenient, to either of the Branch Offices, Rev. C. L. Woodworth, Dist. Sec., 21 Congregational House, Boston, Mass., or Rev. James Powell, Dist. Sec., 112 West Washington Street, Chicago, Ill. A payment of thirty dollars at one time constitutes a Life Member. Letters relating to boxes and barrels of clothing may be addressed to the persons above named.

FORM OF A BEQUEST.

“I bequeath to my executor (or executors) the sum of ——— dollars, in trust, to pay the same in ——— days after my decease to the person who, when the same is payable, shall act as Treasurer of the ‘American Missionary Association’ of New York City, to be applied, under the direction of the Executive Committee of the Association, to its charitable uses and purposes.” The Will should be attested by three witnesses.

The Annual Report of the A. M. A. contains the Constitution of the Association and By-Laws of the Executive Committee. A copy will be sent free on application.

The

American Missionary.

The annual meeting of this Association was held in Plymouth Church, Cleveland, O., Oct. 24–26, and was one of great interest. In this number of the Missionary we have endeavored to give a glimpse of what was said and done. For want of space, almost nothing is published entire except the reports of the committees.

For Dr. Goodell’s sermon on “More Power from Christ for the World’s Larger Needs,” Dr. Ward’s paper on “Caste in Education,” Dr. Noble’s on “God’s Way of Vindicating Brotherhood” and Dr. Roy’s on “The New South,” we must for the present refer our readers to The Advance of November 2d.

The papers read before the Women’s Meeting by Mrs. Andrews, Miss Cahill and Miss Hamilton are reserved for mention in the January Missionary.

The addresses given by Dr. Gregory, Dr. Rust and Mr. Beard, representing the Baptist, the Methodist and the Society of Friends may be used in compiling a pamphlet relating to the work done among the freedmen. Other addresses or papers may also be given in pamphlet form.

That part of the report of the Committee on Finances at our Annual Meeting which says: “More ample facilities for church and educational work bring with them larger demands for funds, so that simply to preserve its efficiency in fields already occupied, the Association requires an annual increase in contributions,” will be readily appreciated by all who are accustomed to study the laws of growth. Every new building either for school or church purposes; every additional scholar, whether among the Negroes, Indians or Chinese; every church and school organized, calls for enlarged expenditures. The recommendation at Cleveland that $50,000 be added to the current income of the Association for general uses during the next fiscal year is based on sound business principles. It is not one dollar more than will be required to give the greatest efficiency[354] to our operations. As in the past, so in the future we must have, if we do what is pressing to be done, money for special purposes.

1. The church work, that has grown so steadily under our care, requires $10,000 for enlargement the coming year.

2. The work contemplated among the Indians, in addition to that carried on by us during the past year, will also require at least $20,000.

3. We have purchased fourteen acres of land at Little Rock, Ark., for a site for the Edward Smith college, and need $25,000 in addition to the amount pledged to provide the buildings needful.

4. We need a new dormitory at Austin, Tex. Allen Hall was crowded to its utmost the day the present school year was opened, and among the first duties of the teachers was the painful one of turning needy students away.

The committee at Cleveland, in urging that $375,000 be raised for the coming year, observes that, “While the receipts for the past two years have been more than $100,000 larger than in the two years next preceding them, the expense of raising and disbursing these funds and managing the affairs of the Association has increased less than $400 per annum, thus showing that the Association is fully equipped for a much larger work without additional cost for the machinery of administration.” We never were in such good condition to do the work we have in hand so economically, wisely and successfully as at present, and there never was a time when the welfare of the nation and the cause of Christ were more fruitful with promise. The voice of the whole people, North, South, East and West, is calling upon us to go forward with renewed strength. Shall we have the means needful?

The thirty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Missionary Association was held in Plymouth Church, Cleveland, Ohio, on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, October 24th to 26th, 1882.

Promptly at three o’clock Tuesday afternoon, the meeting of the Association was called to order by the President, Hon. William B. Washburn, of Massachusetts. Devotional services were conducted by Prof. John Morgan, of Oberlin, after which Gov. Washburn, on assuming the chair for the first time, said:

“I appear before you on this occasion with feelings of a mixed character; partly painful, partly pleasing—painful when I reflect that your expectations in regard to the presiding officer whom you have lately selected probably never will be realized; pleasing—doubly pleasing—to remember that I have received the support of so distinguished an organization as has invited me to preside over its deliberations.

“Let me, then, first of all, thank you for the honor conferred, and assure you that no effort of mine shall be wanting to meet the demands of the occasion.

“I know full well the many trials and difficulties which this Society has been called upon to pass through in the past. Your labors have been for the most part among the neglected and despised races of our country. Society rests upon selfish principles. Men respect the honored and the elevated, not the despised[355] and the down-trodden. Hence a great portion of the labors of this organization has been unknown and uncared-for by the great majority of mankind; and yet it is in the midst of such degradation that we get the brightest glimpses of Christianity, the widest and broadest views of humanity. The aspect to-day which we witness of endeavoring to raise even the lowest masses of mankind into intellectual, moral and spiritual dignity, never was broader than at the present hour. Take courage, then, and feel that your labors have not been in vain. The success which has attended your efforts during the past year, the wonderful increase of the means which have been provided this organization by an enlarged constituency, the bright aspect of the future, ought to strengthen the hands and encourage the hearts of all who are interested in this organization to make greater sacrifices, if need be, in the future than have ever been made in the past.

“Every true citizen, every real patriot ought to feel to-day a special interest in the prosperity and the success of this Society.

“It has been well said that essential to the perpetuity of our republican institutions are two conditions: Popular intelligence and popular morality. In other words, in order that free institutions may be preserved, there must be general intelligence and sound morals. Hence, two institutions are essential—schools and Christian churches. Free institutions without intelligence can exist only in name. It is moral, not physical ills which we have to fear. While the people themselves remain pure no human force can prevail against them.

“When four millions of slaves were suddenly set free the great problem to solve was, what shall we do with them? To-day each vote of those individuals counts as much in the ballot-box as the vote of the most distinguished and intelligent citizen in the land. Would we preserve, therefore, and hand down to our children those institutions which were entrusted to our charge by our fathers, and which have been shedding on us blessings to which all other nations are perfect strangers, then we must educate and Christianize these millions of new-born citizens. I honor this organization especially to-day because it has done more than all other instrumentalities, perhaps, combined to bring about this grand result. Let no one, then, be discouraged or falter at the magnitude of the work; for, if we rise to the level of our opportunity, if we are true to ourselves, victory will sooner or later be ours.”

Rev. George R. Merrill, of Ohio, was then elected Secretary, and Rev. S. M. Newman, of Wisconsin, Assistant Secretary.

The Treasurer, H. W. Hubbard, Esq., then read his report, which was referred to the Committee on Finance.

The annual report of the Executive Committee of the Association was presented by Rev. M. E. Strieby, D.D., Corresponding Secretary of the Society, and its several portions were referred to appropriate committees.

After the appointment of the various committees, the remainder of the session was devoted to prayer and conference, led by Rev. C. L. Woodworth, District Secretary of the Association. This season of prayer derived special interest from the fact that the same hour was observed by the workers throughout the field.

Tuesday evening, after devotional services, led by Rev. Arthur Little, D.D., of Chicago, the annual sermon was preached by Rev. C. L. Goodell, D.D., of St. Louis, from the text, Matthew 28:18, the theme being “More Power from Christ for the World’s Larger Needs.”

After the sermon, Rev. J. E. Twichell, D.D., presented an address of welcome in behalf of the churches and people of Cleveland. The observance of the Lord’s Supper followed, at which Rev. T. M. Post, D.D., of St. Louis, and President J. H. Fairchild, D.D., of Oberlin, presided.

Wednesday morning the prayer meeting was conducted by Rev. H. L. Hubbell, of New York. At the opening of the regular session at nine o’clock, the report of the Committee on the Revision of the Constitution of the Association was presented by Rev. George M. Boynton, of Massachusetts. A general discussion followed, in which the speakers were limited to ten minutes each, and which was closed promptly at half-past ten o’clock. On motion, the report was made the order for two o’clock in the afternoon. Rev. F. L. Kenyon, of Iowa, read a paper on “The Relation of the A. M. A. to Civilization.” Gen. S. C. Armstrong, of Hampton, Va., read a paper on “The Indian Problem,” which was followed by a few remarks from Father Potter, of Ohio, formerly for about twenty years a missionary among the Cherokee Indians. Rev. W. H. Ward, D.D., of New York, read a paper on “Caste in Education.”

After the opening of the Wednesday afternoon session with prayer, the order of the day was taken up and the report of the Committee on the Constitution was referred to a special committee of thirteen, to reconsider the whole subject, and report at the next Annual Meeting, after having obtained an expression of opinion from each of the State Congregational organizations. An invitation was presented to the Association from Mr. and Mrs. D. P. Eells to visit Oakwood on Friday morning, which was received with an expression of thanks. Rev. F. A. Noble, D.D., of Illinois, read a paper on “God’s way of vindicating Brotherhood.” The report of the Committee on African Missions was presented by Rev. M. McG. Dana, D.D., of Minnesota. Rev. Henry M. Ladd, D.D., of New York, using a large map, gave an account of his recent extended missionary explorations on the Upper Nile. Rev. M. E. Strieby, D.D., Secretary of the Association, read a Paper in regard to the proposed exchange of Missions with the A. B. C. F. M., and a special committee was appointed to which the paper was referred. Rev. James Brand, D.D., of Ohio, presented the report of the Committee on Chinese Missions.

Wednesday evening, after opening with devotional exercises, Rev. A. G. Haygood, D.D., of Georgia, delivered an interesting address, followed by addresses from Gen. Clinton B. Fisk, of New York, and Rev. A. J. F. Behrends, D.D., of Rhode Island.

Thursday morning the prayer-meeting was led by Rev. Moses Smith, of Michigan. The business session was opened with prayer by Prof. A. H. Currier, of Oberlin, after which Rev. W. E. Brooks, President of Tillotson Institute, Texas, presented the claims of the work there. The report on Indian Missions was presented by Rev. A. H. Ross, D.D., of Michigan. Prof. G. F. Wright, of Ohio, next presented the report on the Educational Work at the South, and was followed by Mr. B. F. Ousley, a graduate of Fisk University, who spoke upon the report, and also by Prof. A. Salisbury, the recently appointed superintendent of the educational work of the Association. Rev. E. M. Cravath, President of Fisk University, read a paper on “Higher Education.” Rev. Arthur Little, D.D., of Chicago, presented the report of the Committee on Church Work, which was followed by addresses from Rev. C. O. Brown and Mr. Geo. W. Moore, a graduate of Fisk University.

The Woman’s Missionary Meeting was held at nine o’clock Thursday morning in the chapel of the church, when papers were read by Mrs. G. W. Andrews, of Talladega, Ala., Miss Annie Cahill, of Nashville, Tenn., and Miss Hamilton, of Memphis, Tenn.

Thursday afternoon the session was opened with devotional exercises. The Committee on the proposed transfer of missions reported, through Rev. M. McG. Dana, D.D., of Minnesota, favoring the general plan, but making it a condition that the interests of the work already in hand be not sacrificed, and with this condition referring the whole subject to the Executive Committee of the Association,[357] with power. The report was accepted and adopted. A petition was presented by President Ware, of Atlanta University, requesting the appointment of a committee to define the policy of the Association with reference to its work among the different races, which was referred to the Executive Committee. The officers of the Association were re-elected for the ensuing year. Addresses were then made by Rev. J. M. Gregory, D.D., of Washington, D.C., representing the work of the Baptists at the South, and by Rev. R. S. Rust, D.D., of Ohio, representing the Methodists, and by Elkanah Beard, representing the Friends in the same field. These brethren were received in a spirit of cordial fellowship and co-operation. Rev. J. E. Roy, D.D., Field Superintendent of the Association, read a paper on “The New South.” The concluding address of the session was made by Secretary Strieby, representing the work of the Congregational churches at the South. The report of the Finance Committee was presented by J. G. W. Cowles, Esq. Thursday evening a mass meeting was held in the Tabernacle. The music was furnished by a choir of seventy-five voices from Oberlin, under the leadership of Prof. F. B. Rice. After devotional exercises, addresses were made upon “The National Problem of Southern Education,” by ex-President R. B. Hayes, of Ohio: President A. D. White, of Cornell University, and by Hon. J. L. M. Curry, of Virginia. Rev. G. D. Pike, D.D., in behalf of the Association, tendered a resolution of thanks to the churches and people of Cleveland for their hospitality, and to the committees, pastors, choir and railroads for their kindness in contributing to the success of the meetings.

It was the prevailing feeling that the meeting at Cleveland was, on the whole, a great success. Although there were other attractions which drew many away, yet the attendance was large, and at the closing session there were over three thousand present. The weather was fine, the papers presented of a high order, and the interest from beginning to end unabated. Nothing was lacking in the way of preparation, and with the impetus of this meeting resting upon it, the Association takes courage and looks forward to another year of work with renewed faith and hope.

| RECEIPTS. | ||||

| From Churches, Sabbath-schools, Missionary Societies and Individuals | $186,166.62 | |||

| From Estates and Legacies | 78,612.47 | |||

| From Income. Sundry Funds | 7,701.04 | |||

| From Tuition and Public Funds | 24,400.22 | |||

| From Rents, Southern Property | 704.10 | |||

| ————— | $297,584.45 | |||

| Balance on hand Sept. 30th, 1881 | 518.80 | |||

| ————— | ||||

| $298,103.25 | ||||

| ========= | ||||

| EXPENDITURES. | ||||

| The South. | ||||

| For Church and Educational Work, Lands, Buildings, etc. | $230,733.07 | |||

| The Chinese. | ||||

| For Superintendent, Teachers, Rent, etc. | 12,454.45 | |||

| The Indians. | ||||

| For Missionaries and Student Aid | 2,020.00 | [358] | ||

| Foreign Missions. | ||||

| Mendi Mission: | ||||

| For Superintendent, Missionaries, Supplies, etc. | 9,548.70 | |||

| For John Brown Steamer, amt. transferred | 7,002.43 | |||

| Jamaica Mission: | ||||

| For support of aged Missionary | 250.00 | |||

| Publication Account. | ||||

| For American Missionary (22,000 Monthly), Annual Reports (1,500), Circulars, Clerk Hire, Postage, etc. | 9,043.38 | |||

| Cost of Collecting Funds. | ||||

| BOSTON OFFICE. | ||||

| For Salary Rev. G. L. Woodworth, Dist. Sec. | $2,500.00 | |||

| For Salary Rev. Lewis Grout, Agent | 900.00 | |||

| For Traveling Expenses of Dist. Sec. and Agent | 613.21 | |||

| For Clerk Hire, Rent, Printing, Postage, etc. | 1,628.27 | |||

| ———— | 5,641.48 | |||

| CHICAGO OFFICE. | ||||

| For Salary Rev. James Powell, Dist. Sec. | 2,500.00 | |||

| For Traveling Expenses | 540.16 | |||

| For Clerk Hire, Postage, Stationery, etc. | 700.20 | |||

| ———— | 3,740.36 | |||

| MIDDLE DISTRICT. | ||||

| For Salary Rev. O. D. Pike, D.D., Dist. Sec. | 2,500.00 | |||

| For Salary Rev. O. H. White, D.D., Special Work | 355.00 | |||

| For Trav. Expenses, Printing, Postage, etc. | 178.70 | |||

| ———— | 3,033.70 | |||

| Cost of Administration. | ||||

| For Salary Rev. M. E. Strieby, D.D., Cor. Sec. | 3,500.00 | |||

| For Clerk Hire for Cor. Sec. | 1,720.00 | |||

| For Salary of H. W. Hubbard, Treas. | 2,500.00 | |||

| For Clerk Hire | 1,200.00 | |||

| For Rent, Stationery, Printing, Furniture, Janitor, Expressage, Postage, Trav. Ex., etc. | 3,336.99 | |||

| ———— | 12,256.99 | |||

| Miscellaneous. | ||||

| For Expenses in settlement of Legacies | 157.25 | |||

| For Expenses of Annual Meeting | 515.91 | |||

| For Amounts paid Annuitants, balance | 850.86 | |||

| For Amounts refunded, sent Treas. by mistake | 64.84 | 1,588.86 | ||

| ————— | ||||

| $297,313.42 | ||||

| Balance in hand Sept. 30th, 1882 | 789.83 | |||

| ————— | $298,103.25 | |||

| ========= | ||||

| Endowment Funds received, 1881–82. | ||||

| President’s Chair. Talladega College | $15,000.00 | |||

| Graves’ Theo. Scholarships, for Talladega College | 5,000.00 | |||

| Belden Scholarship, Bond of Oregon Short-Line Railway Co., for Talladega College | 1,000.00 | |||

| Fisk University Scholarship, Note of Gen. C. B. Fisk | 500.00 | |||

| Statement of Arthington Mission Fund, for Africa. | ||||

| Balance in hand Sept. 30th, 1881 | 25,477.53 | |||

| Received from Oct. 1, 1881, to Sept. 30, 1882 | 5,172.92 | |||

| ———— | $30,650.45 | |||

| Amount expended | 9,280.53 | |||

| Balance in hand Sept. 30, 1881 | 21,369.92 | |||

| ———— | 30,650.45 | |||

| Statement of Stone Fund. | ||||

| Balance in hand Sept. 30, 1881 | 72,868.03 | |||

| Income in part | 655.47 | |||

| ———— | 73,523.50 | |||

| Expended as follows: | ||||

| Fisk University, Livingstone Missionary Hall, balance | 37,523.50 | |||

| Atlanta University, Stone Hall, in part | 25,081.30 | |||

| ———— | ||||

| $62,604.80 | ||||

| Balance in hand | 10,918.70 | |||

| ———— | 73,523.50 | |||

| RECAPITULATION. | ||||

| American Missionary Association, Current Fund | $297,584.45 | |||

| Endowments for Talladega College | 21,000.00 | |||

| Endowment for Fisk University | 500.00 | |||

| Arthington Fund, appropriated and used during the year | 9,280.53 | |||

| Stone Fund, appropriated and used during the year | 62,604.80 | |||

| ————— | ||||

| $390,969.78 | [359] | |||

| The receipts of Berea College, Hampton N. and A. Institute, and State appropriation of Georgia to Atlanta University, are added below, as presenting at one view the contributions of the same constituency for the general work in which the Association is engaged: | ||||

| American Missionary Association | $390,969.78 | |||

| Berea College | 23,179.00 | |||

| Hampton N. and A. Institute (beside amount through A. M. A.) | 87,865.16 | |||

| Atlanta University | 8,000.00 | |||

| ————— | ||||

| $510,113.94 | ||||

| ========= | ||||

These our fellow-citizens are proving the wisdom of the Government in putting upon them the responsibilities of the elective franchise as at once their defense and their process of education. Taking into account their own aspiration and the force put beneath them by the scheme of Christian schools, we should expect, as we find, a tremendous uplift among them. In this we have assurance as to the future, provided the appliances be worked with increasing vigor. There is in this matter no halting place for the nation. We must lift them up, or they will drag us down. As one of these helping forces, we come to our own

Our system of schools during the year has been working with its full force, and its appliances have been materially extended. The large additions made to our accommodations provided the year before were at once taxed to their utmost, thus proving that our appreciation of the necessity was correct, and that our appeal for the extension had not been made too soon nor too strong. And the enlargement secured during this closing year is now met with the response, “we, too, are full to overflowing.” Of the buildings put up the year before, the two dormitories at Hampton, one for Indian and one for colored youth, have had no empty rooms; at the Atlanta University, the wing built to the Girls’ Hall by the Stone Fund did not have capacity enough for the overflow of the main structure; the Strieby Hall at Tougaloo, brought to completion and dedicated since the opening of the year, had to be supplemented in an extempore way; the Stone Hall at Talladega for boys was filled; the Stone Hall at New Orleans for girls, and for the family of teachers, was only opened to find the need of a boys’ hall; and the Tillotson Institute at Austin, turning the ends of halls into apartments, calls loudly for another building.

During this year, at the Fisk University, the Livingstone Missionary Hall has been brought to completion and furnished, providing dormitories for 121 male students, also a chapel, library and recitation rooms. The total cost, $60,000, came from the Stone Fund. This structure, which, in its name, embraces the highest idea of the greatest African explorer, is next Monday to come to its dedication, and some of our friends are to go hence to participate in that service—the address to be delivered by Professor Northrop, of Yale College. At the Atlanta University, the Stone Hall, as the central building of the group, has been erected at an expense of $40,000, and will soon be ready for occupancy. Greatly commodious, and comely enough to relieve the plainness of the halls on either side, it will furnish a chapel, library, reading room and recitation rooms. This structure, as well as the Stone Halls at Nashville, Talladega and New Orleans, has had the wise supervision of Prof. T. N. Chase, who has occupied, meantime, his favorite chair of Greek, and who, as a builder, has shown the rare gift of always keeping[360] within his appropriations. At Macon, Ga., to the Lewis High School we have built a two-room “annex,” to which also was added a wing for the library which is there growing up. At Athens, Ga., our Knox Institute has been renovated, and in it a chapel fitted up for the new church. At Mobile, Ala., our Emerson Institute, that had been burned the second time, has been rebuilt upon an enlarged scale, and at an expense not far beyond the insurance money. At Talladega, the President’s house has been finished, and two cottages on land adjoining our premises have been bought for the use of two of our mission families, one of them being named after Mr. Seth Wadhams, of Chicago, who gave the $1,500 for the purchase. At Marion, a house was built for a parish school. At Athens, the Trinity School Building to accommodate 150 scholars and the family of teachers, has been completed at a cost to the Association of $8,000. For this the colored people themselves made the needed two hundred thousand brick, mixing the clay by the tramp of their one small steer, and they have their proportionate interest in the property. At the laying of the corner stone, the local editor, the Postmaster and the Principal of the Ladies’ Seminary of the place, made appreciative addresses, and Miss Wells had her Jubilee. In Little Rock, Ark., at a cost of $5,500, we have bought and fenced a tract of 14 acres, overlooking that city, as a site for the Edward Smith College, which has been chartered by the State, being so named from a gentleman in Massachusetts who gave the money to buy the land, and who to a surplus now in hand intends to add enough to make his donation $19,000. This institution is greatly needed in that grandly opening State, where there is, as yet, no provision for the higher education of the colored people. This last planting will about complete our circle of State institutions. At Fayetteville, Ark., our Howard School Building has been overhauled, and in it we have re-opened our own school. So at Lexington, Ky., we have refitted our High School Building, and have resumed our own school, the city for the last six years having had the use of the house. At Camp Nelson, the trustees of the Academy are erecting a new three-story building under the lead of the Rev. John G. Fee.

At the South we count 8 chartered institutions, 11 high and normal schools, and 38 common schools—in all 57. During the year we have employed 241 teachers, an increase over the last year of 11. Of these, 13 have performed the duties of matrons and 15 have been engaged in the business departments. The number of students has been 9,608, a gain of 500 over last year. Of these, 72 have been in the theological department, 28 in the law, 104 in the collegiate, 139 in the preparatory, 2,542 in the normal, 1,103 in the grammar, 2,185 in the intermediate, and 3,481 in the primary.

The theological departments at Howard, Talladega and Straight have been doing their good work in training upon the ground just the sort of men who are needed for the peculiar work to be done. Fisk University has three of its graduates in the study of theology at Oberlin, and one in a divinity school at Yale. The law department of the Straight, with a faculty made up of five of the best lawyers in New Orleans, has had 20 students, who are of both races, and who, upon their diplomas, by the statute, are admitted to the bar of all the courts of the State. We are pushing more and more the lines of industrial training. The two farms at Talladega and Tougaloo have this year been put into better shape than ever before. Tougaloo raises fine fruits for the Chicago market and fine stock for the surrounding country. Both raise much of the beef and pork and vegetables for their own use. Atlanta University is pushing fine gardening, teaching the girls of the senior class cookery, and is planning to go into a school of carpentry. The Fisk, this year, under a trained hospital nurse, introduces hygienics and cookery. The Le Moyne, at Memphis, teaches cooking, nursing and sewing.[361] All of our boarding-schools require a certain amount of work. The Storrs school, in Atlanta, has opened this fall a genuine kindergarten under an expert teacher. The Avery Institute, at Charleston, is going into the same, with training also in the use of tools.

But to all intellectual and secular training there needs to be added moral and religious cultivation. This is kept as our steady aim. No teacher is sent out who is not in fellowship with some church, and who does not profess to be actuated in going by a missionary spirit. The large number of conversions, the frequent revivals in these institutions, and the developed fruit of good living, attest the fidelity of these missionary teachers. The judgment day alone can reveal the influence of these consecrated workers, the most of whom are women, upon the life and character of the multitude of youth who have been under their care. The pupils are watched over in the class-room, in the place of religious assembly, and out of school hours. They are invited to private conferences for the correction of habits and views, and there the concerns of the soul are considered; scholars are prayerfully followed up even into vacation by correspondence, until not a few in these ways are led to Christ and into His church. The most of our young men, who are examined for entering the ministry, in giving their religious history, trace it back to the time when they were led to the Saviour by some of their teachers, whose richest reward it must be to see these young men coming into the ministry with ample equipment largely through their own influence. Women’s work for women is the modern discovery of missions. Of those who go abroad, their work is largely that of teaching. Our lady workers, of whom we have 200, besides the 40 in Howard, Hampton and Berea, who are reckoned as teachers, are usually missionaries as really as those who go abroad, or go South under that title. Of this last class of workers, of whom we have twelve, there are some who are very apostles in the garb of womanly delicacy. They teach mothers and daughters things which belong to their sex; they lead to the tidiness and comfort of home; they gather the maternal meetings and lead in the same; they labor in revivals; they become assistant pastors, being often, as the young pastors testify, their own best teachers and guides. The soldiers of the Union are worthy of all the praise and the gratitude they have received, but here has been a small army of heroines, who, forgetful of the best chances, came after the pomp of war, to serve not for three years, but for ten, twelve, fifteen, seventeen years, growing gray by work and by the anxieties and privations of the field, breaking down in health and wearing out their lives, ostracised and despised by those about them, who ought to have given sympathy and succor, and not sustained as they should have been at home, of whom the world is not worthy, but who must have a large place in the heart of Him, who, in their isolation, has been the companion of each one, and who, at the last, shall say, “She hath done what she could, she hath chosen the good part.”

Before the war and since, the wealthy people at the South had a full supply of colleges and seminaries, besides the free use of the best institutions in the North, so that their children were well educated. But there was a class of white people who could avail themselves of no such advantages and for whom there were no free public schools. As a consequence they fell into a distressing state of ignorance and poverty; they lost aspiration; they felt themselves in a hopeless class; and they are just there now. From the beginning our institutions have been open to pupils of all races. As yet the colored youth have been almost alone in entering them. But it is thought that, as they shall be seen shooting ahead, as prejudice shall wear away, many of these worthy white young people will go where they can get an education, a better one, and at a less cost, than anywhere else. A Confederate Colonel says that this will come about in ten years. Already[362] in the medical department of the Howard University, of the 93 students two-thirds are white, while some of the Professors are colored, though accomplished in their profession. In the law department of the Straight at New Orleans there are more white than colored students. Some of the best teachers in the white public schools of Atlanta have visited the class-rooms of our University there, with the purpose frankly avowed of making improvement in the art of teaching. In the country white teachers have gone to those who had been trained at Atlanta to learn their normal methods of instruction and of management. May not such yet say we will go to that training school for ourselves, and get those improvements at first hand? We have one notable illustration of what may be done, and that is at Berea, Ky. This college, planted before the war by the Association, upon being opened after the war, allowed colored scholars to come. After some effervescence the institution settled into its color-blind method, until it has become a great power in the State with the colors in about equal proportion among the students and at the grand commencement convocations. Some of the young folks coming down from the mountains to Berea say they would rather go there than to endure the manners of the aristocratic colleges. The citizens of Cabin Creek, Ky., our old ante-bellum battle ground, are just now erecting an Academy with the money subscribed upon the condition of no caste. The influence of Berea College is felt up in all the mountain country. White youth come down there to get stores of knowledge to carry back. The Professors have gone through that region lecturing on education, holding teachers’ institutes and preaching. At Clover Bottom, 20 miles out, they have gotten up such a mixed school, which is a success, and is now under the patronage of this Association. The Committee have decided to offer those mountain people the aid of our system, if they will only allow the very few colored scholars to enter the schools. Up there the colored children in a whole county are scarcely numerous enough to call for more than one school, and so the law forbidding such mixed public schools is a virtual closing of the doors of knowledge to this class. The Committee have made an appropriation for this work and have already had their Field Superintendent upon a tour of exploration—his report being favorable to kind, patient, persevering endeavor to get the school-master abroad through a region wherein whole counties the few school-houses are cabins with scarcely a glass window in them.

In the growth of the educational department and in the purpose of the Committee to do the very best work in our institutions, it has been found needful to secure the service of an expert in school processes who should help to the most approved methods of organization, discipline, instruction and unification. Accordingly Mr. Albert Salisbury, who had been a Professor in the State Normal, at Whitewater, Wis., and a conductor of teachers’ institutes, has been appointed Superintendent of Education, and has already entered upon service, giving promise of great effectiveness in his line. Doctor Roy will continue in his position as Field Superintendent.

At the first some of our best friends thought that the Association was too slow in its church work; but all now, we think, agree that the wisdom of experience justifies the process which mainly through our schools grows its own timber, out of which to build its churches, taking the young people thus trained and the adults who are converted to the standard of Christian living and away from the superstitions and immoralities of the old time. At first view this would seem to be a tedious process. But it is surprising how soon the youth run up to maturity and[363] to become the leaders of churches, the best of which have come on by this nurture. Then there are some adult people, noble natures, of a childlike spirit, who gain by absorption and take on the ideas of the younger folks. In this way, through these seventeen years since the war, our churches have come on from two or three to number 83, which is an average of five a year. Nor are these merely skeleton churches. Every one of these 83 has a pastor, except one whose minister died a short time ago. Of the 73 ministers who serve these 83 churches, 22 are from the North, and 51 are native preachers. Every one of these churches except seven has its own house of worship, or chapel, and there are only four of these that depend upon the college chapels for their places of religious assembly. Some of these are rude in structure; the most are plain but comely; four or five are of brick and of commanding appearance; all are blessed sanctuaries. Many friends, in going through the South, are pleasantly disappointed in finding these churches so well housed. Nor, for young churches, are these deficient in encouraging numbers. They have a total of 5,641 members, an average of 68, while the average membership of the Congregational churches west of the Mississippi River is only 45, and of all west of Pennsylvania, 63. The additions on profession were 709; the Sunday-school scholars numbered 1,835; the amount raised for church purposes $9,306, and the benevolent contributions reached $1,496.50.

It is beautiful to see how readily these plain people take up the New Testament idea of church government, and how this natural process tends to their education and discipline of character. Herein we find confirmation that the Apostle made no mistake in setting up such churches among the Christians of his day who had not been trained in New England. These churches in the South are known everywhere as insisting upon a high standard of ethics. Their example, their methods, their influence, are greatly stimulating to the churches round about them, so that by quality they make up in part for want of quantity. These churches are organized into seven conferences. Many persons have smiled upon reading the reports of these convocations, and have wondered how such an ecclesiastical body would seem, whether its members were not simply playing at an ecclesiastical parliament. Our suggestion is, come and see. If you were to come, you would find a fulfillment of the Saviour’s words, “All ye are brethren,” the white and the colored being members of the same body. You would find a rigidity of parliamentary usage. You would find literary exercises, discussions, reports, Sunday-school assemblies, devotional services going on after the manner of those with which you are familiar. Some of our brethren testify that these meetings seemed to afford as much intellectual and spiritual stimulus as those which they were accustomed to attend before going South. An additional feature of these gatherings is the presence and participation of the lady missionaries and teachers, whose reports are greatly interesting. In Alabama the conference has associated with it a Ladies’ Missionary Society with auxiliaries in different parts of the State. The exercises of these women’s meetings are not only to cultivate the missionary spirit, but to help the wives, mothers and daughters of this people to be missionaries of sweetness and light, of order and comfort, in their own homes. These ecclesiastical assemblies become not only a representative of our work in its spirit and extent, but they become occasions for drawing out the fellowship of the pastors and churches, white and colored, where they meet. At first these bodies were ignored. Now it is a common thing for the local pastors to drop in upon them, to participate in the exercises and to offer their pulpits for supply. This has been done at Wilmington, Macon, Mobile, Marion and Selma.

During the last year, six new churches have been organized, those at Williamsburg, Ky.; Cedar Cliff, N.C.; Athens, Ga.; Meridian, Miss.; Eureka and Topeka,[364] Kan. All of these are supplied with pastors. Athens uses the assembly-room of our Knox Institute; Meridian for the present rents rooms for the church and school; Eureka and Topeka have both built houses of worship. New meeting-houses have also been built at Caledonia, Miss.; Fausse Point, La., and Luling, Tex. Paris, Tex., has replaced its big shanty by a fine church edifice. Childersburg, Ala., burnt out, has rebuilt with great self-denial on the part of the people. Mobile, burnt out, is to be accommodated for a time in the assembly-room of the Emerson Institute, rebuilt since the fire. The church at East Savannah, blown down, has been rebuilt. The suburban church at Louisville, Ga., also blown down, is still in its ruins. At Five Mile, out from the city, a mission house has been built. By the wonderful enterprise of their pastor, Rev. A. A. Myers, the people have put up a commodious house at Williamsburg, Ky., in the mountain country. The town is sixty years old, and this is the first church brought to completion, three others having rotted down during the process of building. The church at Clover Bottom, Ky., has been supplied with a school-house sanctuary through the aid secured by President Fairchild, of Berea. The great church at Midway, Ga., has been finished up. The church at Anniston, Ala., has been enlarged. So during the year ten churches have been erected.

The closing year has not been without its comforting measure of spiritual influence. The dew has been in the fleece of most of our churches and schools. In some of them individual cases of conversion have been the reward of large faith and zeal. In others, clusters of souls have been won to Christ. Distinctive revivals have been enjoyed at Chattanooga and Memphis, Tenn.; McIntosh and Macon, Ga.; Marion, Ala.; New Orleans, Talladega College, and in the Fisk, Atlanta and Tougaloo Universities. The total number of additions to our Southern churches on profession is 709. Those who in our missions have been led to Christ but who have gone to other churches would nearly double that number. The total number of members in all our Southern churches is 5,641.

When our last annual meeting was in session we had two parties upon the ocean on their way to Africa. Mr. I. J. St. John and Rev. J. M. Hall were going to reinforce the Mendi Mission, and Superintendent Ladd and Dr. Snow were going to explore the Upper Nile with reference to locating the Arthington Mission if the project should prove feasible. Mr. St. John was to be the business manager and to have charge of the John Brown steamer which was to be built. Mr. Hall, from the theological department of the Howard University, was to take charge of the Good Hope Station. He readily got hold of the work and proved himself an acceptable and successful missionary. He has the church, and a native teacher has the school under his supervision. Mr. Hall, being of the sturdy mountain stock of East Tennessee, has endured the climate well, and we can but hope that an extended career of usefulness is before him. Mr. St. John, by his own unavoidable exposure on his voyages between Freetown and Mendi, and up the rivers to our stations, was himself made sick, and so was confirmed in the judgment that called for the steamer as a means of preserving the health of our missionaries. The English Governor-General of the West Coast agreed with Mr. St. John to give the steamer the carrying of the mail and of all Government freight between Freetown and Mendi, which is an English dependency. The transportation of supplies for the Mission and the marketing of the lumber of our mill, the only one on the West Coast, call for this steam craft. All views conspire to put down the “John Brown” as one of the most effective missionaries to be introduced to that region,[365] where there are no roads nor beasts of burden and where the water highway is the main reliance. It was thought best that Mr. St. John should not take the risk of the first wet season at the Mission, and so he returned to this country, coming over by a sailing vessel to save expense. He makes the gratifying report that in his intercourse along the coast he found many evidences of the good influence of the Mendi Mission in its training of men who have gone out into the ways of business, and who retain their integrity of character. He named the noble chief of a tribe where is located the vigorous Shengay Mission, who, with his son, had been educated at our Good Hope Station. Rev. A. E. Jackson has continued in charge of the Avery Station and boarding-school. During the year the Mission was afflicted in the death of Rev. J. M. Williams, of the Kaw Mendi Station, who, after having endured fifteen years of service in Africa, succumbed to the disease of diabetes. Rev. Mr. Jowett, one of the native preachers, is acceptably supplying Mr. Williams’ place at Kaw Mendi. Mr. Jowett has a son now in the Fisk University, who gives promise of making himself a useful man in his native land. The other three lads from the Mendi Mission at school at Hampton and at Atlanta, are doing well. The Debia Station is under the care of Mr. and Mrs. Goodman.

Dr. Ladd and Dr. Snow, having made their long and perilous tour, which took them up the Nile 2,500 miles, have returned. They report no sufficiently inviting location for a mission in the region of the Sobat. They recommend that Khartoum be occupied as a base of operations, and that a school be established on the east bank of the river opposite the city, which lies in the junction of the Blue and White Niles. That site is quite healthy. They would have a steamer by which to communicate with the Arthington district of the Upper Nile. The Executive Committee, of course, had to submit to the inevitable, as indicated by the double revolt, and voted to put the mission into complete abeyance for the time.

Though the Indian once had the continent to himself, he yet seems to be “the man without a country.” And the Christian missions which have sought to identify him with his native land have with him been driven along before the advancing tide of the white man’s migration. So has it been from the days of Jonathan Edwards, John Eliot and David Brainard down to these times of the Riggses and Williamsons. The Indian missions of this Association have fared in the same way, those at Northfield, Mich., and those at Cass Lake and Red Lake, Minn., which were served by some fifteen missionaries, among them Revs. S. G. Wright, J. B. Bardwell and A. Barnard. Of these the venerable Mr. Wright still abides in the service, being now at Leech Lake. Returning this year to his field, he writes: “We were very happy to find the little company of earnest, devoted Christians, whom we left two years before, still faithfully pursuing their work for God. They are truly the salt of the earth, burning lights in this great darkness, the spiritual power in the place.” Again he says: “I wish I could attend the annual meeting. I should love to give the friends a short history of the conversion and rich Christian experience of numbers of those around us.” Our church at S’Kokomish, Washington Territory, Rev. Myron Eells, pastor, during the year has swarmed, seven of its members having taken letters to unite with four other Christians of the Clallam Indians to form a Congregational Church at Jamestown. One infant was baptized. A half-dozen white neighbors came in and communed with them. Mr. Eells says that the services were held in Chinook, Clallam, English, Chinook translated into Clallam, and English translated into Clallam, a Pentecostal gift of tongues. The work of the mother church has been[366] more encouraging this year than the last. Five have united with the church on profession of faith. The service of the agents at the S’Kokomish, Fort Berthold and Sisseton agencies has been about as usual in routine and outcome. The work that is now going on at the Hampton Institute in the educational and industrial training of 89 young Indians of both sexes is truly encouraging; not only as to its immediate accomplishment, but as to its future bearings upon the welfare of the Indians, and upon the Indian question itself. At the last commencement, the Indian classes claimed their full share of attention, and showed an improvement in the general character of the pupils over last year. One noted speech was made by an Indian youth. Rev. Dr. Bartend, referring to that speech in his address, said: “Two hundred and fifty years ago there came floating into this beautiful harbor vessels from the old country. What was their object? What was their hope? The prayer that arose from their decks was this: ‘God give us strength that we may educate and Christianize the Indian.’ William and Mary College, now almost ready to perish, is the monument of their endeavor. They did not see the answer to their prayer. God works in His own way, in His own time, with His own men. Could they see what we to-day behold, they would say, as do we, Speed on. God speed this glorious school.” Although the Association, which founded and developed the Hampton, has surrendered its control to a Board, yet besides aiding in the support of the pastor, who cares for the three races, associated in the one church of the place, it also makes a special appropriation toward the Indian department of the Institute. The Association will be ready to co-operate with the Government under its new appropriation, using some of its own institutions for the instruction and training of Indian youth. It has been proposed that the Association take up a new mission among a neglected tribe in the deep Northwest. Gen. Armstrong, by his recent tour among the several Indian tribes of that region, has been able to make judicious suggestions which will be duly considered.

But a little while ago we were praying God to open the door of China; and now the Chinese are pressing in at our own back door, having a steam ferry between our shore and theirs. Even the building of our Chinese wall, while China has been tearing down hers, has had the immediate effect of hastening 25,000 of these people in at our Golden Gate before the law should go into effect, and this influx has been felt already in our schools, which for the last few months have had a total larger than that of any former months. Mr. Pond certifies that even the enforcement of the law will not for some time occasion any let up in the pressure upon our school accommodations. We have as stock on hand, as raw material, these 125,000 people whom we should work up in the Christianizing way, so that they may be prepared, some for their own mission work at home, and some to receive the masses who may come by-and-by when the embargo is lifted. So that while our government stands at the Golden Gate to warn off any Mayflower immigrants, it may be that this enforced quiet and isolation will become a mighty factor in the scheme for Christianizing China. But none the less is it a ludicrous object lesson that the nation which stands with its front door wide open to receive 90,000 Europeans a month, should yet shudder over the 125,000 Mongolians who in many years have sought admission at the back door. It is a humiliating confession that 50,000,000 of Christian people, compacted as a nation, should shrink from having their system come into contact with the effete superstitions of 125,000 sojourners. But the politicians’ law is only for ten years. The principle, the conscience[367] of the nation will be at work. The law may become a dead letter or be repealed. Before we are aware of it, the flood-gates may be raised and a great tide may set in. So, in any event, we have herein a grand opportunity, a mighty obligation.

Our last Annual Report mentioned a desire on the part of the converted Chinamen in California and their friends, that a mission be located at some well-chosen point in Southern China, from which their Christian brethren going back to fatherland might go forth to carry the Gospel to their countrymen. Further consideration has settled it that Hong Kong, the centre of the district from which most of our California Chinamen come, is the proper location. Such a mission would give a Christian greeting to the returning Christian Chinamen, would furnish an atmosphere and an instrumentality for keeping up their spiritual life, would be a training-school for those who should become missionaries, would be a rallying centre there, and would be the point of juncture between our work on the coast and that heathen empire. But, as it is the purpose of this Association not to extend its operations abroad, we made a distinctive proposition to the American Board that it take up the proposed mission at Hong Kong, and so work in harmony with us on this side the Pacific. We are glad to report that this overture has been cordially acceded to, and that that venerable missionary body accepts this “sacred trust.” Our brethren of the Chinese Christian Association out there have in hand already a fund of $700, which they intend to put into that mission as an offering of the first fruits.

In its work on the Pacific Coast, the Association is represented by its auxiliary, the California Chinese Mission, whose President is Rev. Dr. John K. McLean, and whose Secretary is Rev. Wm. C. Pond, who, in addition to the care of his city parish, has the supervision of our operations there. Taking up the work into his own mind and heart, he gives to it an amount of study, watch-care and service that is marvellous. With a Pauline spirit, he goes the round of the missions, cheering and directing the workers, healing divisions and laying new plans.

Our fifteen schools are located at Berkeley, Marysville, Oakland, Oroville, Petaluma, Point Pedro, Sacramento, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, Stockton, and at San Francisco, where are the five missions, No. 1, No. 2, Barnes, Bethany, and West. The work of the year has been greatly encouraging. These schools have been taught by thirty-one teachers, of whom eleven are Christianized Chinamen.

The total number of scholars enrolled during the year was 2,567, a gain over the previous year of 935, while that year had a gain over the former one of 76. Of these during the past year 156 have ceased from idolatry and 106 have given evidence of conversion. Nor do these figures give the full number of those who are brought to the light in our schools, for many are scattered and cannot attend them. The whole number of those of whom we have hope that they are born of God in connection with our work from the first, Mr. Pond thinks cannot be less than 431, and wisely does he add: “The figures will cease to look dry and the statistical table will glow with even a celestial light, if we but reflect that every unit in these numbers stands for an undying soul, and every unit in some of them for such a soul brought out from the dark bondage of Chinese paganism into the glorious liberty of the sons of God.”

It is proposed now to re-establish our mission at Los Angeles, which, as the original, gave way for a time to another that came in but has turned out a failure. Chico, where there are many Chinese, and no one to care for them, is another place where the Superintendent could start a mission. So also the door seems to be opening for yet another school in San Francisco at the great Pioneer Wooden[368] Mills, where 600 Chinese are employed. And so the expanding work demands the additional appropriation which the Committee have already voted, making a total of $13,000 to be used.

At our last annual meeting we reported a total of $243,795.23, which was a gain of $56,315.12, or 20 percent, over that of the previous year. One year ago the Committee felt constrained to ask that this sum should be carried up to $300,000 for the support and enlargement of the varied work in charge. We started out well. Then in the spring our chariot came to dragging heavily with a debt of $25,000 upon it. Then there was a rally, and the fiscal year came to its close, Sept. 30, with $297,584.45, which is a gain of $53,789.22 over the last year, or 22 per cent. Besides the current receipts we have received toward the endowment of the President’s chair in Talladega College, $15,000; and for scholarships in the same, $6,000; also a Scholarship note for $500, in behalf of Fisk University, which makes a total of $319,584.45 received into our treasury during the year. This leaves the treasury out of debt, with a balance in hand of $789.83, and an increase of endowment fund of $21,500. For this accomplishment we offer devout thanks to Almighty God.

The exigencies of the work, the enlargement of the expenditure made almost inevitable by the new buildings and increased facilities, will scarcely be met by $300,000 the coming year. An increase of that amount by 20 per cent, could be most economically and wisely expended without any attempt at undue enlargement. The legitimate and almost irresistible progress of the work demands that. But we are the servants of our constituents, and assume not to decide. We can most efficiently use the increase, but will faithfully work as best we can with the means entrusted to us. We can only add that the work will suffer if less than the $300,000 be secured.

As boys run backward that they may jump the further forward, so we may profitably compare the receipts of this Association in its earlier years with those of this last year. The nearly $300,000 just announced is equal to the total of contributions for the first ten years. And the total for the year, as given by the Treasurer, of the contributions from the same constituency for the general work in which the Association is engaged, more than $500,000, is equal to the receipts into our treasury for the first fourteen years.

Never have the affairs of this Association seemed more prosperous; never have its labors on the field yielded a more abundant and precious fruitage; never has it seemed more firmly established in the confidence of the people, both at the North and the South; never has it shared more fully the favor of God!

May we have grace to walk so humbly before God, and so honestly and faithfully before men, in the administration of our trust, that His favor and their confidence may abide upon us!

The Committee to whom has been referred the subject of the educational work of this Association, beg leave to report that we heartily approve the policy of the Association by which it has put its main efforts upon the Christian education of teachers for the colored people. Our Congregational churches, while it is important to plant them, are not the first need. They can enter but slowly. The people do not appreciate them nor ask for them. Education they beseech us for. The lower common-school education we can supply only here and there. We thank God, and we recognize it as a blessed evidence of the growth of healthy public sentiment, that every year more and more attention is paid in the States of the South to free public education, and that in this the colored people are having their part, and that the expense of supporting their schools is more and more cheerfully borne. But the States which are willing to educate children are not all ready as yet to educate their teachers. Whether the common schools of the South are good, depends on whether the schools for teachers are good. We believe there is no other agency which is doing so much to secure teachers for the colored youth of the South as the American Missionary Association. This is a task which does not carry with it ecclesiastical profit; but it carries the blessing of the Great Head of the Church, as it has the good will of good men in every communion.

Apprehending the paramount importance of this work, we would impress upon the officers of this Association, what they doubtless feel, the importance of raising their chartered institutions and normal schools to the very highest possible grade. Bricks and mortar are necessary, good buildings are noble, but the first demand is for good teaching, for the very best instruction which Northern culture can secure. A few extra hundreds paid to a competent principal may be of more real use than many thousands paid for a building. Our consecrated wealth will provide the buildings. That we do not fear for; but it needs great and rare executive wisdom to see that these buildings shall be put to their best use for the best instruction. Now is the molding time for the colored people, and they need to be molded aright. Good education in barracks is better than poor education in a palace. It has been the boast of our constituency that they have known how to educate. They have supported the best colleges in the North. They are now supporting the best schools in the South. We are glad that, apprehending these duties, the Association has just appointed a competent Superintendent of Education, whose special business it will be to see to it that the standard of education shall be raised to the highest possible grade. We would especially recommend that all our institutions be carefully examined, that we call nothing college or university whose course of instruction falls below the grade which belongs to the name, and that, if it be necessary in any case, inferior teachers be weeded out and their places supplied by such as are competent and earnest. This we urge, while knowing that our institutions, as a rule, are models in all the South, because we would not have the Association satisfied with that to which we have already attained, and because we believe that our schools can and should be made so superior to other institutions that they shall attract white pupils as well as black, or break down the walls of caste.

We see with satisfaction the progress made in Howard and Talladega in theological education, which has been followed by the organization of numerous prosperous[370] churches. We would urge that, as soon as possible, Fisk and Straight universities be supplied with similar active departments of theological instruction.

Industrial departments have been made very useful in Hampton and Tougaloo. These institutions are models in these as in other respects. The explanation rests in part in the great enthusiasm or ability of the gentlemen whom we are so fortunate as to have in charge of those institutions, and who have a special gift in developing these departments, and in part in the fortunate locality in which these institutes are placed. While we would be glad to have similar instruction given in Fisk, Atlanta, and elsewhere, we recognize the great difficulty of doing similar work in cities. Domestic labor should be encouraged, to relieve the expense of board; but experiments in establishing schools of carpentry, blacksmithing, nursing, etc., while excellent, need to be made with the greatest care, and under the supervision of such teachers as possess the requisite enthusiasm and faith.

We would especially urge, in this connection, on those who manage our institutions, that they impress on the pupils the virtues of thrift and self-support. The students who have come to us are no longer ex-slaves. They have all been reared in freedom. They should be required to pay a reasonable amount for tuition. This should be imposed as an educating influence. They should be made to understand that when education is given it represents a money value as well as does the food that goes into the stomach. More and more should they be required to pay their tuition, if it be but a dollar a month, that they may understand its value. The aggregate of this will be of considerable help, as it will elevate the educational notions of the people.

We are glad to see that our chartered institutions are making progress toward independence of the Association. For this they should work by the increase of their endowments for instruction. We express our great thanks to the generous friends who have so nobly given for these purposes, and especially to the wise and generous benevolence of Mrs. Stone, which has made this a marked year in the history of our institutions. May the Lord reward her, and may her example stir up many more.

Our work would not be complete without a more formal and a most cordial recognition of the thanks we owe to the self-denying teachers of our institutions. They are men and women of most admirable culture; they have made the greatest sacrifices; they have entered with the warmest enthusiasm into their work. We have been greatly pleased with the professional enthusiasm of those at the head of some of our excellent normal schools, to whom no words of praise can be extravagant. The progress in nearly all our institutions has been such as to merit our heartiest appreciation. We commend this, our great work, to the generous hearts of our Christian constituency.

G. F. Wright, Chairman.

BY PRES. E. M. CRAVATH, FISK UNIVERSITY.

1. The negroes are citizens, and vested with all the rights, duties and responsibilities of American citizenship. The ballot is in their hands, and as a necessary consequence they will share the offices of trust and responsibility. There must and will be political leaders among them. It might be better for the country if the colored people would use the ballot purely, with an eye single to the best interests of society; if they should always vote for the wisest, most honest and most capable men, uninfluenced by personal prejudices, race distinction, or the popular excitement of heated political campaigns, and with no aspiration for[371] political distinction or the honors and spoils of office. It might be better for the country if the citizens of other races would do this. But how unlike the Anglo-Saxon or the Celt would be the African if he should do it. But, fortunately, or unfortunately, there is about as much genuine human nature in the American citizen of African descent as there is in those of European; and we must expect essentially the same results under like conditions. It will not prevent colored men from having political aspirations, and from being elected to offices of trust and responsibility, to confine education among them to public, normal and industrial schools. The safer and better way is to give to the young men who have aspirations for a higher education the opportunities and advantages they seek, just as they are provided for the youth of other races.

2. The six millions of colored people in the South are organized into distinct and separate churches, which are ministered to by persons of their own race. This is the result both of choice and necessity. The white churches are not open to them, and as a general thing they prefer to have their separate organizations. The influence and power of the minister among the colored people are exceedingly great. No people stand more in need of an intelligent, wise and educated ministry, and among no people can such a ministry do such a noble work for the proper training of the young men who are to constitute the religious teachers and guides of these six millions of colored American citizens just delivered from bondage, and now making trial before the world of freedom and citizenship. I urge the necessity of institutions for higher education.

The public schools of the South for colored children are in general taught by colored teachers. This is usually demanded by the parents. In these public schools there are hundreds of positions such as are filled in white schools by men who have had their training in the best colleges and universities of the South, and why should not colored young men be given the same training for the same responsibilities and duties? The same principles and necessities hold in the departments of law and medicine. Is there any reason, in the nature of the case, why a young colored man does not need to have as good an education to fit him for these professions as a young white man does? In all enlightened countries, institutions of higher education are regarded as indispensible; they accomplish a work in the interests of society, the Church and the State, which cannot be left out with safety to any race or any country. But there are weighty reasons why the colored youth of the South need the advantages of a higher education. They have received less by inheritance. Education, discipline, culture, the habits and surroundings of life through generations, to some extent, at least, determine the inherited intellectual and moral qualities of individuals, families and races. The colored youth begins life without the inherited qualities which can come only through generations of civilization.

Then, too, he has not had the advantages (and these are among the greatest children can possess) of a cultured home, refined and intellectual associations, a purified and stimulating social life, and the instruction of an educated ministry. These have largely been denied him in his earlier years. Thus, when young colored men or women set out to secure an education that shall put them on a high plane of intellectual life and give them a fair chance to work a career which shall entitle them to be honestly ranked among the educated and cultured of the white race in the higher departments of the world’s work, they find themselves at a great disadvantage.

How shall this be overcome, except by patient, long-continued and wisely-directed study? Aspiration must mature into purpose and purpose ripen and harden into character. Intellectual labor must be encouraged and even exacted until it[372] becomes comparatively easy and pleasurable. Habits of study and investigation must be formed and the judgment must be matured. Where shall the young men of the South get these advantages except in schools for higher education? But there is one more consideration which I wish to urge. These six millions are the representatives of a race 200,000,000 strong and of a continent. No equal body of Africans was ever before placed in a condition so favorable for the development of whatever possibilities there are in the race. Under slavery they have been disciplined to toil and have learned the lessons of work; they have come to like the ways of civilized life and have acquired a desire and taste for its comforts and luxuries. Pagan worship and heathen superstitions have been largely destroyed, and the people have accepted the Christian religion. They are widely scattered among their fellow citizens of other races, and they have intrusted to them the full duties, and have resting upon them all the responsibilities of citizenship. Whatever possibilities are in the race can here be developed in a shorter time and by a more direct way than in the case of any section of Africa. So the race is on trial, and every aid should be given in order that the best possible result may be reached. Who can properly estimate the power for good which colleges and universities, founded in the right spirit, strongly administered and wisely adapted to the wants and necessities of the people, can exert in determining the future of the negro in this country and the future of the great African race?

The church work of the Association during the year has been steady, growthful, and encouraging. Quite the average of progress has been attained. This will readily appear by reference to a few statistics. Six new churches have been added to the list, making in all eighty-three. Ten houses of worship have been erected. It is a remarkable fact that every one of the eighty-three churches, except one whose minister died a short time ago, has a pastor. And equally remarkable that fifty-one of these pastors are native preachers. As showing the value of theological seminaries established by the Association, and the ability and usefulness of trained colored men, the average membership of sixty-eight in each church exceeds the average of all the Congregational churches west of Pennsylvania. The addition of 709 on profession, and the conversion of about an equal number who have found other church homes, make an average of seventeen conversions to each church, an increase of 20 per cent. Where else can an equally good exhibition be made? Only about one to a church throughout the country. There are seven churches which have added from twenty-five to forty-five to their membership. There are only six that report no additions. So far as reported all but eleven churches contribute money for church purposes. Thirty-seven report benevolent contributions. One church reports $350, another church reports $158, another church reports $86, another church reports $83, another church reports $60, another church reports $50. Seventy-four Sunday-schools are reported. One Sunday-school has over 500 members, another 400 members, ten schools 200 members, and seven schools 100 members. These figures indicate vitality in the churches, for Sunday-schools do not thrive very well, excepting where there is activity in the churches with which they are associated. In nine localities precious revivals have been enjoyed. The local associations indicate growth in fellowship and power. When we remember that these results have been reached amid manifold hindrances and discouragements[373] arising from ignorance, prejudice, superstition and vice, we may well exclaim, “What hath God wrought?” “Thank the Lord and take courage.” But the best results of the year do not admit of tabulation. The unwritten history of these churches are the tears, the struggles, the sacrifices, the prayers, the burdens silently, uncomplainingly borne. This is their real history. God knows it all, and those who have been the patient workers in its making will be remembered in that day when he counts up his jewels. Then it must not be forgotten that these churches represent almost infinitely more in the South than their small number would indicate. They are tonic in their influence upon all the other churches around them. Their simple New Testament polity, which encourages self-government and self-development, their high standard of ethics, which is a constant rebuke to an emotional religion apart from morality, make them peculiarly lights shining in dark places, and invest them with that quiet, but inscrutable transforming power that belongs to good leaven.

In this has been vindicated the wisdom of the policy which has preferred quality to quantity, good character to great numbers, intelligent piety to ignorant devotion, a pure life to a noisy profession. Without doubt the Association might have doubled its present number of churches during these seventeen years. It has cost something to move slowly in this matter.

We have said that the past year has witnessed the average growth. The rate of progress during the last seventeen years has been uniformly very constant, about five churches a year. Ten years ago six new churches and ten houses of worship were reported. The question now comes whether it is not quite time to change the rate by doubling it, at least to quicken the pace. The church work is initial and fundamental. It underlies all else. The Association is in the South for no other purpose than to make Christian manhood and womanhood. For this glorious work the church of God is the divinely appointed agency. Others are auxiliary. There is but one opinion as to the sore need of more churches. The Macedonian cry is heard in many directions.

It has been demonstrated that Congregational churches can exist and thrive west of the Hudson and south of Mason and Dixon’s line.

The polity and faith of the Pilgrim Fathers is not for the elect few but the unsaved many. And if the methods, influence, and example of our churches in the South are greatly stimulating to the churches round about them, that is an additional argument for their multiplication.