Project Gutenberg's A Manual of Ancient History, by M. E. Thalheimer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: A Manual of Ancient History Author: M. E. Thalheimer Release Date: March 13, 2018 [EBook #56734] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A MANUAL OF ANCIENT HISTORY *** Produced by Adrian Mastronardi and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BY

M. E. THALHEIMER,

FORMERLY TEACHER OF HISTORY AND COMPOSITION IN THE PACKER COLLEGIATE

INSTITUTE, BROOKLYN, N. Y.

VAN ANTWERP, BRAGG & CO.,

137 WALNUT STREET,

CINCINNATI.

28 BOND STREET,

NEW YORK.

THALHEIMER’S HISTORICAL SERIES.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by

WILSON, HINKLE & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

ECLECTIC PRESS:

VAN ANTWERP, BRAGG & CO.,

CINCINNATI.

Several causes have lately augmented both the means and the motives for a more thorough study of History. Modern criticism, no longer accepting primitive traditions, venal eulogiums, partisan pamphlets, and highly wrought romances as equal and trustworthy evidence, merely because of their age, is teaching us to sift the testimony of ancient authors, to ascertain the sources and relative value of their information, and to discern those special aims which may determine the light in which their works should be viewed. The geographical surveys of recent travelers have thrown a flood of new light upon ancient events; and, above all, the inscriptions discovered and deciphered within half a century, have set before us the great actors of old times, speaking in their own persons from the walls of palaces and tombs.

Nor is the new knowledge of little value. If we look familiarly into the daily life of our fellow-men thousands of years ago, it is to find them toiling at the same problems which perplex us; suffering the same conflict of passion and principle; failing, it may be, for our warning, or winning for our encouragement; in any case, reaching results which ought to prevent our repeating their mistakes. The national questions which fill our newspapers were discussed long ago in the Grove, the Agora, and the Forum; the relative advantages of government by the many and the few, were wrought out to a demonstration in the states and colonies of Greece; and no man whose vote, no woman whose influence, may sway in ever so small a degree the destinies of our Republic, can afford to be ignorant of what has already been so wisely and fully accomplished.[iv] Present tasks can only be clearly seen and worthily performed in the light of long experience; and that liberal acquaintance with History which, under a monarchical government, might safely be left as an ornament and privilege to the few, is here the duty of the many.

The present work aims merely to afford a brief though accurate outline of the results of the labors of Niebuhr, Bunsen, Arnold, Mommsen, Rawlinson, and others—results which have never, so far as we know, been embraced in any American school-book, but which within a few years have greatly increased the treasures of historical literature. While it may have been impossible, within our limits, to reproduce the full and life-like outlines in which they have portrayed the characters of ancient times, we have sought, with their aid, at least to ascertain the limits of fact and fable. With but few exceptions, and those clearly stated as such, we have introduced no narrative which can reasonably be doubted.

The writer is more confident of justice of aim than of completeness of attainment. No one can so acutely feel the imperfections of a work like this, as the one who has labored at every point to avoid or to remove them; to compress the greatest amount of truth into the fewest words, and while reducing the scale, to preserve a just proportion in the details. To hundreds of former pupils, who have never been forgotten in this labor of love, and to the kind judgment of fellow-teachers—some of whom well know that effort has not been spared, even where ability may have failed—this Manual is respectfully submitted.

Brooklyn, N. Y., April, 1872.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| Sources of History. | 9. |

| Dispersion of Races; Periods and Divisions of History. | 10. |

| Auxiliary Sciences: Chronology and Geography. | 11. |

| BOOK I. Asiatic and African Nations, from the Dispersion at Babel to the Rise of the Persian Empire. |

|

| Part I.—The Asiatic Nations. | |

| View of the Geography of Asia. | 13. |

| History of the Chaldæan Monarchy. | 17. |

| The Assyrian Monarchy. | 18. |

| The Median Monarchy. | 22. |

| The Babylonian Monarchy. | 24. |

| Kingdoms of Asia Minor. | 29. |

| Phœnicia. | 30. |

| Syria. | 33. |

| Judæa. | 34. |

| (a) Theocracy. | 35. |

| (b) United Monarchy. | 36. |

| (c) The Kingdom of Israel. | 39. |

| (d) The Kingdom of Judah. | 42. |

| Part II.—The African Nations. | |

| Geographical Outline of Africa. | 48. |

| History of Egypt. | 50. |

| (a) The Old Empire. | 51. |

| (b) The Shepherd Kings. | 53. |

| (c) The New Empire. | 55. |

| Religion and Ranks in Egypt. | 61. |

| History of Carthage. | 66. |

| BOOK II. The Persian Empire, from the Rise of Cyrus to the Fall of Darius. |

|

| Career of Cyrus. | 73. |

| Reign of Cambyses. | 76. |

| Organization of the Empire by Darius I. | 79. |

| Invasions of Europe under Darius. | 83. |

| The Behistûn Inscription. | 87. |

| [vi]Invasion of Greece by Xerxes. | 88. |

| Reign of Artaxerxes I. (Longimanus) | 92. |

| Xerxes II. | 94. |

| Sogdianus; Darius II. | 95. |

| Artaxerxes II. (Mnemon). | 96. |

| Artaxerxes III.; Arses. | 98. |

| Darius III. (Codomannus). | 99. |

| BOOK III. Grecian States and Colonies, from their Earliest Period to the Accession of Alexander the Great. |

|

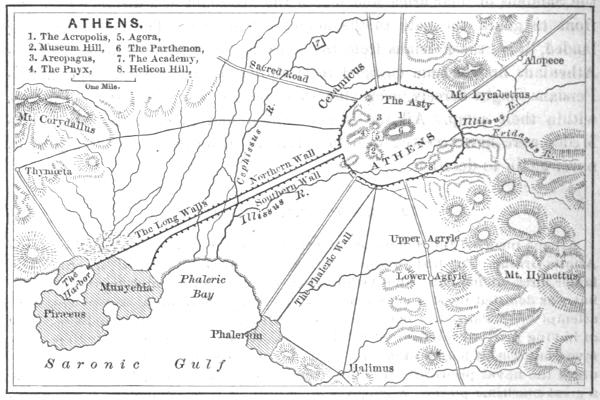

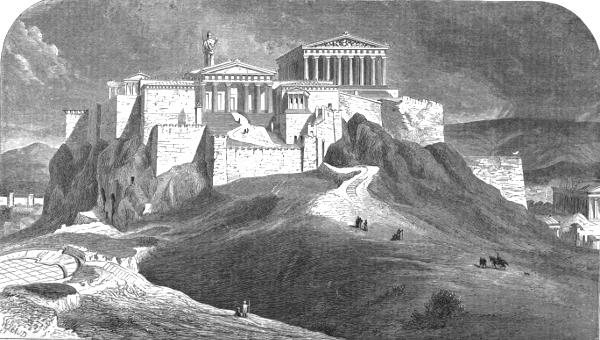

| Geographical Outline of Greece. | 105. |

| History of Greece. | 107. |

| First Period. | |

| Traditional and Fabulous History, from the Earliest Times to the Dorian Migrations. | 107. |

| Greek Religion. | 110. |

| Second Period. | |

| Authentic History, from the Dorian Conquest of the Peloponnesus to the Persian Wars. | 116. |

| Sparta. | 118. |

| Athens. | 124. |

| Grecian Colonies. | 130. |

| Third Period. | |

| From the Beginning of the Persian Wars to the Macedonian Supremacy. | 134. |

| Invasions by Mardonius and Datis. | 134. |

| The Battle of Marathon. | 135. |

| Invasion by Xerxes; Battle of Thermopylæ. | 138, 139. |

| Battle of Salamis, and Retreat of Xerxes. | 141. |

| Battles of Platæa and Mycale. | 144. |

| Hellenic League, and Greatness of Athens. | 145. |

| The Peloponnesian War. | 161. |

| The Sicilian Expedition. | 169. |

| Decline of Athens. | 175. |

| Battle of Ægos-Potami, and Fall of Athens. | 179. |

| Spartan Supremacy. The Thirty Tyrants. | 181. |

| The Corinthian War. | 184. |

| Peace of Antalcidas. | 187. |

| Theban Supremacy. | 188. |

| Theban Invasions of the Peloponnesus. | 192-195. |

| The Social War. | 195. |

| The Sacred War. | 196. |

| Battle of Chæronea. Supremacy of Philip of Macedon. | 197. |

| BOOK IV. History of the Macedonian Empire, and the Kingdoms formed from it, until their Conquest by the Romans. |

|

| First Period. | |

| [vii]From the Rise of the Monarchy to the Death of Alexander the Great. | 201. |

| Second Period. | |

| From the Death of Alexander to the Battle of Ipsus. | 206. |

| Third Period. | |

| History of the Several Kingdoms into which Alexander’s Empire was Divided. | 209. |

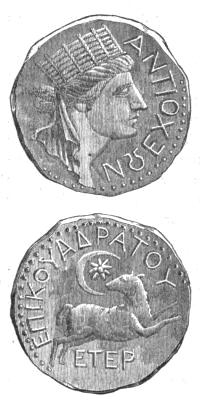

| Syrian Kingdom of the Seleucidæ. | 209. |

| Egypt under the Ptolemies. | 216. |

| Macedonia and Greece. | 222. |

| Thrace; Pergamus. | 230. |

| Bithynia. | 231. |

| Pontus. | 232. |

| Cappadocia; Armenia. | 234. |

| Bactria; Parthia. | 235. |

| Judæa, under Egypt and Syria. | 237. |

| Under the Maccabees. | 238. |

| Under the Herods. | 240. |

| BOOK V. History of Rome, from the Earliest Times to the Fall of the Western Empire. |

|

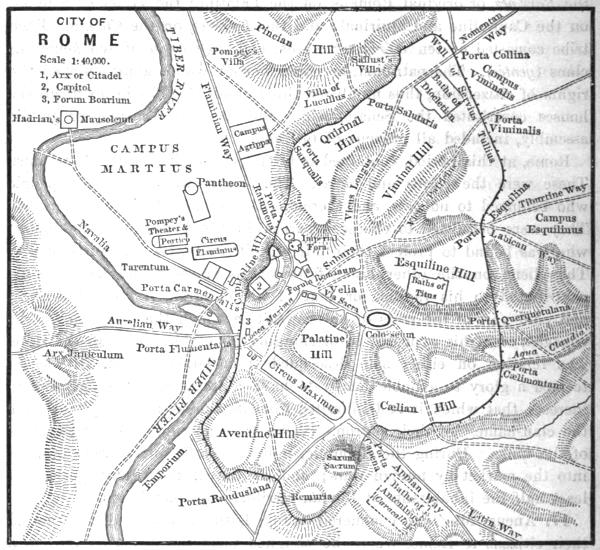

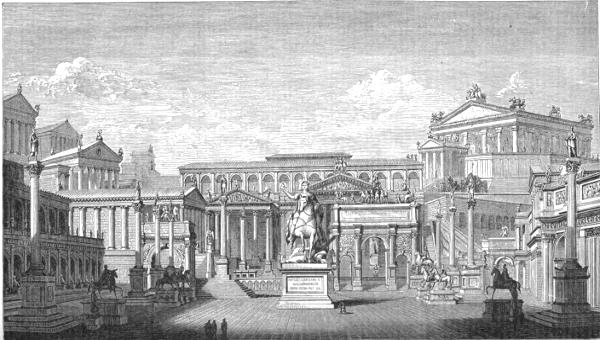

| Geographical Sketch of Italy. | 245. |

| I. History of the Roman Kingdom. | 248. |

| Religion of Rome. | 255. |

| II. History of the Roman Republic. | 260. |

| First Period. Growth of the Constitution. | 260. |

| Laws of the Twelve Tables. | 265. |

| Capture of Rome by the Gauls. | 269. |

| Second Period. Wars for the Possession of Italy. | 274. |

| First Samnite War. | 274. |

| Latin War, and Battle of Vesuvius. | 275. |

| Second Samnite War. | 276. |

| Third War with Samnites and the Italian League. | 278. |

| War with Pyrrhus, King of Epirus. | 279. |

| Colonies and Roads. | 282. |

| Third Period. Foreign Wars. | 283. |

| First Punic War. | 284. |

| War with the Gauls. | 286. |

| Second Punic War, and Invasion of Italy by Hannibal. | 287. |

| Battles of the Trebia, Lake Thrasymene, Cannæ. | 288, 289. |

| Wars with Antiochus the Great; with Spain, Liguria, Corsica, Sardinia, and Macedon. | 293. |

| Third Punic War. | 294. |

| Subjugation of the Spanish Peninsula. | 295. |

| Fourth Period. Internal Commotions and Civil Wars. | 296. |

| Reforms Proposed by the Gracchi. | 297. |

| Jugurthine Wars, and Rise of Marius. | 299. |

| Defeat of the Teutones and Cimbri. | 302. |

| [viii]Servile Wars in Sicily. | 303. |

| The Social War. | 304. |

| Exile and Seventh Consulship of Marius. | 305. |

| Dictatorship of Sulla. | 306. |

| Sertorius in Spain. | 307. |

| War of the Gladiators. | 308. |

| Extraordinary Power of Pompey. | 311. |

| Conspiracy of Catiline. | 312. |

| Triumvirate of Pompey, Cæsar, and Crassus. | 314. |

| Conquests of Cæsar in Gaul, Britain, and Germany. | 315. |

| Civil War; Pompey defeated at Pharsalia. | 319. |

| Cæsar Victor at Thapsus, and Master of Rome. | 321. |

| Murder of Cæsar in the Senate-house. | 323. |

| Triumvirate of Antony, Cæsar Octavianus, and Lepidus. | 324. |

| Antony defeated at Actium; Octavianus becomes Augustus. | 325. |

| III. History of the Roman Empire. | 326. |

| First Period. | |

| Reigns of Augustus, 326; Tiberius, 328; Caligula, Claudius, 330; Nero, 331; Galba, Otho, Vitellius, 333; Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, 334; Nerva, Trajan, 335; Hadrian, T. Antoninus Pius, M. Aurelius Antoninus, 336; Commodus, 337. | |

| Second Period. | |

| Reigns of Pertinax, Didius Julianus, 338; Severus, Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabalus, 339; Alexander Severus, 340; Maximin, the Gordians, Pupienus and Balbinus, Gordian the Younger, Philip, Decius, 341; Gallus, Æmilian, Valerian, Gallienus and the “Thirty Tyrants,” 342; Aurelian, Tacitus, Florian, 343; Probus, Carus, Numerian, Carinus, 344. | |

| Third Period. | |

| Reigns of Diocletian and Maximian with two Cæsars, 345; of Constantine, Maximian, and Maxentius in the West—Galerius, Maximin, and Licinius in the East, 348; of Constantine alone, and the Reörganization of the Empire, 349; of Constantine II., Constans, and Constantius II., 350; of Julian, Jovian, and Valentinian I., 352; of Valens, 353; of Gratian, Valentinian II., and Theodosius I., 354. | |

| Fourth Period. | |

| Final Separation of the Eastern and Western Empires. | 356. |

| Reigns, in the West, of Honorius, 356; of Valentinian III., 358; of Maximus, 359; of Avitus, Marjorian, Libius Severus, Anthemius, Olybrius, Glycerius, and Julius Nepos, 360; of Romulus Augustulus, 361. | |

| MAPS. | |

| I. The World as known to the Assyrians. | facing 17. |

| II. Empire of the Persians. | ” 97. |

| III. Ancient Greece and the Ægean Sea. | ” 113. |

| IV. Empire of the Macedonians. | ” 209. |

| V. Italy, with the Eleven Regions of Augustus. | ” 257. |

| VI. The Roman Empire. | ” 305. |

1. The former inhabitants of our world are known to us by three kinds of evidence: (1) Written Records; (2) Architectural Monuments; (3) Fragmentary Remains.

2. Of these the first alone can be considered as true sources of History, though the latter afford its most interesting and valuable illustrations. Several races of men have disappeared from the globe, leaving no records inscribed either upon stone or parchment. Their existence and character can only be inferred from fragments of their weapons, ornaments, and household utensils found in their tombs or among the ruins of their habitations. Such were the Lake-dwellers of Switzerland, and the unknown authors of the shell-mounds of Denmark and India, the tumuli of Britain, and the earthworks of the Mississippi Valley.

3. The magnificent temples and palaces of Egypt, Assyria, and India have only afforded materials of history since the patient diligence of oriental scholars has succeeded in deciphering the inscriptions which they bear. Within a few years they have added immeasurably to our knowledge of primeval times, and explained in a wonderful manner the brief allusions of the Bible.

4. The oldest existing books are the Hebrew Scriptures, which alone[1] of ancient writings describe the preparation of the earth for the abode of man; his creation and primeval innocence; the entrance of Sin into the world, and the promise of Redemption; the first probation, and the almost total destruction of the human race by a flood; the vain attempt of Noah’s descendants to avert similar punishment in future by building a “city and[10] a tower whose top may reach unto heaven,” and their consequent dispersion. The Bible lays the foundation of all subsequent history by sketching the division of the human race into its three great families, and describing their earliest migrations.

5. The family of Shem, which was appointed to guard the true primeval faith, remained near the original home in south-western Asia. Of the descendants of Ham, a part settled in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, and built the great cities of Nineveh and Babylon; while the rest spread along the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean, and became the founders of the Egyptian Empire. The children of Japheth constituted the Indo-Germanic, or Aryan race, which was divided into two great branches. One, moving eastward, settled the table-lands of Iran and the fertile valleys of northern India; the other, traveling westward along the Euxine and Propontis, occupied the islands of the Ægean Sea, and the peninsulas of Greece and Italy. By successive migrations they overspread all Europe.

6. Our First Book treats of the Hamitic and Semitic empires. With the rise of the Medo-Persian monarchy, the Aryan race came upon the scene, and it has ever since occupied the largest place in History. The Hamitic nations were distinguished by their material grandeur, as exemplified by the enormous masses of stone employed in their architecture, and even in their sculpture; the Semitic, by their religious enthusiasm; the Indo-Germanic, by their intellectual activity, as exhibited in the highest forms of art, literature, and political organization.

7. History is divided into three great portions or periods: Ancient, Mediæval, and Modern.

Ancient History narrates the succession of empires which ruled Asia, Africa, and Europe, until the Roman dominion in Italy was overthrown by northern barbarians, A. D. 476.

Mediæval History begins with the establishment of a German kingdom in Gaul, and ends with the close of the fifteenth century, when the revival of ancient learning, the multiplication of printed books, and the expansion of ideas by the discovery of a new continent, occasioned great mental activity, and led to the Modern Era, in which we live.

8. Ancient History may be divided into five books:

| I. | History of the Asiatic and African nations, from the earliest times to the foundation of the Persian Empire, | B. C. 558. |

| II. | History of the Persian Empire, from the accession of Cyrus the Great to the death of Darius Codomannus, | B. C. 558-330. |

| III. | History of the States and Colonies of Greece, from their earliest period to the accession of Alexander of Macedon, | B. C. 336. |

| IV. | History of the Macedonian Empire, and the kingdoms formed from it, until their conquest by the Romans. | |

| V. | History of Rome from its foundation to the fall of the Western Empire, | A. D. 476. |

9. In the study of events, the two circumstances of time and place constantly demand our attention. Accordingly, Chronology and Geography have been called the two eyes of History. It is only by the use of both that we can gain a complete and life-like impression of events.

10. For the want of the former, a large portion of the life of man upon the globe can be but imperfectly known. There is no detailed record of the ages that preceded the Deluge and Dispersion; and even after those great crises, long periods are covered only by vague traditions. We have no complete chronology for the Hebrews before the building of Solomon’s Temple, B. C. 1004; for the Babylonians before Nabonassar, B. C. 748; or for the Greeks before the first Olympiad, B. C. 776. When its system of computation was settled, each nation selected its own era from which to date events; but we reduce all to our common reckoning of time before and after the Birth of Christ.

11. The study of Geography is more intimately connected with that of History than may at first appear. The growth and character of nations are greatly influenced, if not determined, by soil and climate, the position of mountains, and the course of rivers.

Note.—It is recommended to Teachers that the Geographical sections which precede Parts 1 and 2 of Book I, Book III, and Book V, be read aloud in the class, each pupil having his or her eye upon the map, and pronouncing the name of each locality mentioned, only when it is found. By this means the names will become familiar, and questions upon the peculiarities of each country can be afterward combined with the lessons. Many details necessarily omitted from maps I., II., IV., and VI., will be found on maps III. and V.

Pupils are strongly urged to study History with the map before them; if possible, even a larger and fuller map than can be given in this book. Any little effort which this may cost, will be more than repaid in the ease with which the lesson will be remembered, when the places where events have occurred are clearly in the mind.

12. Asia, the largest division of the Eastern Hemisphere, possesses the greatest variety of soil, climate, and products. Its central and principal portion is a vast table-land, surrounded by the highest mountain chains in the world, on whose northern, eastern, and southern inclinations great rivers have their rise. Of these, the best known to the ancients were the Tigris and Euphra´tes, the Indus, Etyman´der, Arius, Oxus, Jaxar´tes, and Jordan.

13. Northern Asia, north of the great table-land and the Altai range, is a low, grassy plain, destitute of trees, and unproductive, but intersected by many rivers abounding in fish. It was known to the Greeks under the general name of Scythia. From the most ancient times to the present, it has been inhabited by wandering tribes, who subsisted mainly upon the milk and flesh of their animals.

14. Central Asia, lying between the Altai on the north, and the Elburz, Hindu Kûsh, and Himala´ya Mountains on the south, has little connection with ancient History. Three countries in its western part are of some importance: Choras´mia, between the Caspian and the Sea of Aral; Sogdia´na to the east, and Bac´tria to the south of that province. The modern Sam´arcand is Maracan´da, the ancient capital of Sogdiana. Bactra, now Balkh, was probably the first great city of the Aryan race.

15. Southern Asia may be divided into eastern and western sections by the Indus River. The eastern portion was scarcely known to the[14] Persians, Greeks, and Romans; and materials are yet lacking for its authentic history: the western, on the contrary, was the scene of the earliest and most important events.

16. South-western Asia may be considered in three portions: (1) Asia Minor, or the peninsula of Anato´lia; (2) The table-land eastward to the Indus, including the mountains of Arme´nia; (3) The lowland south of this plateau, extending from the base of the mountains to the Erythræ´an Sea.

17. Asia Minor, in the earliest period, contained the following countries: Phry´gia and Cappado´cia, on its central table-land, divided from each other by the river Ha´lys; Bithy´nia and Paphlago´nia on the coast of the Euxine; Mysia, Lydia, and Caria, on that of the Æge´an; Lycia, Pamphyl´ia, and Cilic´ia, on the borders of the Mediterranean. It possessed many important islands: Proconne´sus, in the Propon´tis; Ten´edos, Les´bos, Chi´os, Sa´mos, and Rhodes, in the Ægean; and Cy´prus, in the Levant´.

18. Phrygia was a grazing country, celebrated from the earliest times for its breed of sheep, whose fleece was of wonderful fineness, and black as the plumage of the raven. The Ango´ra goat and the rabbit of the same region were likewise famed for the fineness of their hair. Cappadocia was inhabited by the White Syrians, so called because they were of fairer complexion than those of the south. The richest portion of Asia Minor lay upon the coast of the Ægean; and of the three provinces, Lydia, the central, was most distinguished for wealth, elegance, and luxury. The Lydians were the first who coined money. The River Pacto´lus brought from the recesses of Mt. Tmolus a rich supply of gold, which was washed from its sands in the streets of Sardis, the capital.

19. The Grecian colonies, which, at a later period, covered the coasts of Asia Minor, will be found described in Book III.[2] This peninsula was the field of many wars between the nations of Europe and Asia. From its intermediate position, it was always the prize of the conqueror; and after the earliest period of history, it was never occupied by any kingdom of great extent or of long duration.

20. The highlands of south-western Asia contained seventeen countries, of which only the most important will here be named. Arme´nia has been called the Switzerland of Western Asia. Its highest mountain is Ar´arat, 17,000 feet above the sea-level. From this elevated region the Tigris and Euphrates take their course to the Persian Gulf; the Halys to the Euxine; the Arax´es and the Cyrus to the Caspian Sea. Colchis lay east of the Euxine, upon one of the great highways of ancient traffic. It was celebrated, in very early times, for its trade in linen. Media was a mountainous region, extending from the Araxes to the Caspian Gates. Persia[15] lay between Media and the Persian Gulf. Its southern portion is a sandy plain, rendered almost desert in summer by a hot, pestilential wind from the Steppes of Kerman. Farther from the sea, the country rises into terraces, covered with rich and well-watered pastures, and abounding in pleasant fruits. The climate of this region is delightful; but it soon changes, toward the north, into that of a sterile mountain tract, chilled by snows, which cover the peaks even in summer, and affording only a scanty pasturage to flocks of sheep.

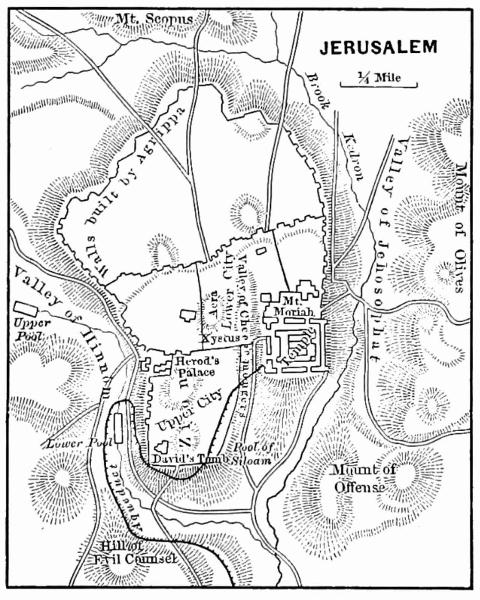

21. The lowland plain of south-western Asia comprised Syr´ia, Arabia, Assyr´ia, Susia´na, and Babylo´nia. Syria occupied the whole eastern coast of the Mediterranean, and consisted of three distinct parts: (1) Syria Proper had for its chief river the Oron´tes, which flowed between the parallel mountain ranges of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon. (2) Phœni´cia comprised the narrow strip of coast between Lebanon and the sea. (3) Palestine, south of Phœnicia, had for its river the Jordan, and for its principal mountains Hermon and Carmel. Syria becomes less fertile as it recedes from the mountains, and merges at last into a desert, with no traces of cities or of settled habitations. Yet even this sandy waste is varied by a few fertile spots. The site of Palmy´ra, “Queen of the Desert,” may be discerned even now in her magnificent ruins. In more prosperous days she afforded entertainment to caravans on their way from India to the coast of the Mediterranean.

22. Arabia is a vast extent of country south and east of Syria, lying between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Though more than one-fourth the size of Europe, it was of little importance in ancient times; for its usually rocky or sandy soil sustained few inhabitants, and afforded little material for commerce.

Assyria Proper lay east of the Tigris and west of the Median Mountains. The great empire which bore that name varied in extent under different monarchs, and the name of Assyria is often applied to all the territory between the Zagros Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. The region between the two great rivers and north of Babylonia was called by the Greeks Mesopota´mia. It differed from the more southerly province in being richly wooded: the forests near the Euphrates more than once supplied materials for a fleet to Roman emperors in later times.

Susiana lay along the Tigris, south-east of Assyria. It was crossed by numerous rivers, and was very rich in grain. Its only important city was Susa, its capital.

23. Babylonia comprised the great alluvial plain between the lower waters of the Tigris and Euphrates, and sometimes included the country south of the latter river, on the borders of Arabia Deserta, which is better known as Chaldæ´a. When the snows melt upon the mountains of Armenia, both rivers, but especially the Euphrates, become suddenly[16] swollen, and tend to overflow their banks. In fighting against this aggression of Nature, the Babylonians early developed that energy of mind which made their country the first abode of Eastern civilization. The net-work of canals which covered the country served the three purposes of internal traffic, defense, and irrigation. Immense lakes were dug or enlarged for the preservation of surplus waters; and the earth thrown out of these excavations formed dykes along the banks of the rivers. The fertile plain, so thoroughly watered, produced enormous quantities of grain, the farmer being rewarded with never less than two hundred fold the seed sown, and in favorable seasons, with three hundred fold. We shall not be surprised, therefore, to learn that Babylonia was, from the earliest times, the seat of populous cities, crowded with the products of human industry, and that its people long constituted the leading state of Western Asia. Though the plain of Babylonia afforded neither wood nor stone for building, Nature had provided for human habitations a supply of excellent clay for brick, and wells of bitumen which served for mortar. (Gen. xi: 3.)

24. South-eastern Asia. India extends from the Indus eastward to the boundaries of China, being bounded on the south by the Indian Ocean, and on the north by the Himala´yas, from whose snowy heights many great rivers descend to fertilize the plains. The richness of the soil fits it for the abode of a swarming population; and roads, temples, and other structures, dating from a very remote period, attest the skill and industry of the people. Herod´otus[3] names them as the greatest and wealthiest of nations, though he had not seen them. It was only in the fifth century before Christ that the Indian peninsulas became distinctly known to the Greeks; and it was two centuries later, in the invasion by Alexander, that the remarkable features of the country were first described to the Western world by eye-witnesses. “Wool-bearing trees” were mentioned as a most peculiar production; for cotton, as well as sugar, was first produced in India. The pearl fisheries, however, of the eastern coast, the diamonds of Golcon´da, the rubies of Mysore´, as well as the abundant gold of the river-beds, the aromatic woods of the forests, and the fine fabrics of cotton, silk, and wool, for which India was already famous,[4] drew the merchants of Phœnicia at a much earlier period to the banks of the Indus.

25. China was even less known than India to the inhabitants of the ancient world. The province of Se´rica, which formed the north-western[17] corner of what is now the Chinese Empire, was visited, however, by Babylonian and Phœnician merchants, for its most peculiar product, silk. The extreme reserve of the Chinese in their dealings with foreigners, may already be observed in the account given by Herodotus of their trade with the neighboring Scythians. The Sericans deposited their bales of wool or silk in a solitary building called the Stone Tower. The merchants then approached, deposited beside the goods a sum which they were willing to pay, and retired out of sight. The Sericans returned, and, if satisfied with the bargain, took away the money, leaving the goods; but if they considered the payment insufficient, they took away the goods and left the money. The Chinese have always been remarkable for their patient and thorough tillage of the soil. Chin-nong, their fourth emperor, invented the plow; and for thousands of years custom required each monarch, among the ceremonies of his coronation, to guide a plow around a field, thus paying due honor to agriculture, as the art most essential to the civilization, or, rather, to the very existence of a state.

26. After the dispersion of other descendants of Noah from Babel,[5] Nimrod, grandson of Ham, remained near the scene of their discomfiture, and established a kingdom south of the Euphrates, at the head of the Persian Gulf. The unfinished tower was converted into a temple, other buildings sprang from the clay of the plain, and thus Nimrod became the founder of Babylon, though its grandeur and magnificent adornments date from a later period. Nimrod owed his supremacy to the personal strength and prowess which distinguished him as a “mighty hunter before the Lord.” In the early years after the Flood, it is probable that wild beasts multiplied so as to threaten the extinction of the human race, and the chief of men in the gratitude and allegiance of his fellows was he who reduced their numbers. Nimrod founded not only Babylon, but E´rech, or O´rchoë, Ac´cad, and Cal´neh. The Chaldæans continued to be notable builders; and vast structures of brick cemented with bitumen, each brick bearing the monarch’s or the architect’s name, still attest, though in ruins, their enterprise and skill. They manufactured, also, delicate fabrics of wool, and possessed the arts of working in metals and engraving on gems in very high perfection. Astronomy began to be studied in very early times, and the observations were carefully recorded. The name of Chaldæan became equivalent to that of seer or philosopher.

27. The names of fifteen or sixteen kings have been deciphered upon[18] the earliest monuments of the country, but we possess no records of their reigns. It is sufficient to remember the dynasties, or royal families, which, according to Bero´sus,[6] ruled in Chaldæa from about two thousand years before Christ to the beginning of connected chronology.

1. A Chaldæan Dynasty, from about 2000 to 1543 B. C. The only known kings are Nimrod and Chedorlao´mer.

2. An Arabian Dynasty, from about 1543 to 1298 B. C.

3. A Dynasty of forty-five kings, probably Assyrian, from 1298 to 772 B. C.

4. The Reign of Pul, from 772 to 747 B. C.

During the first and last of these periods, the country was flourishing and free; during the second, it seems to have been subject to its neighbors in the south-west; and, during the third, it was absorbed into the great Assyrian Empire, as a tributary kingdom, if not merely as a province.

28. At a very early period a kingdom was established upon the Tigris, which expanded later into a vast empire. Of its earliest records only the names of three or four kings remain to us; but the quadrangular mounds which cover the sites of cities and palaces, and the rude sculptures found by excavation upon their walls, show the industry of a large and luxurious population. The history of Assyria may be divided into three periods:

| I. | From unknown commencement of the monarchy to the Conquest of Babylon, | about | 1250 B. C. |

| II. | From Conquest of Babylon to Accession of Tiglath-pileser II, | 745 B. C. | |

| III. | From Accession of Tiglath-pileser to Fall of Nineveh, | 625 B. C. |

One king of the First Period, Shalmaneser I, is known to have made war among the Armenian Mountains, and to have established cities in the conquered territory.

29. Second Period, B. C. 1250-745. About the middle of the thirteenth century B. C., Tiglathi-nin conquered Babylon. A hundred and twenty years later, a still greater monarch, Tiglath-pileser I, extended his conquests eastward into the Persian mountains, and westward to the borders of Syria. After the warlike reign of his son,[19] Assyria was probably weakened and depressed for two hundred years, since no records have been found. From the year 909 B. C., the chronology becomes exact, and the materials for history abundant. As´shur-nazir-pal I carried on wars in Persia, Babylonia, Armenia, and Syria, and captured the principal Phœnician towns. He built a great palace at Ca´lah, which he made his capital. His son, Shalmane´ser II, continued his father’s conquests, and made war in Lower Syria against Benha´dad, Haza´el, and A´hab.

30. B. C. 810-781. I´va-lush (Hu-likh-khus IV) extended his empire both eastward and westward in twenty-six campaigns. He married Sam´mura´mit (Semi´ramis), heiress of Babylonia, and exercised, either in her right or by conquest, royal authority over that country. No name is more celebrated in Oriental history than that of Semiramis; but it is probable that most of the wonderful works ascribed to her are purely fabulous. The importance of the real Sammuramit, who is the only princess mentioned in Assyrian annals, perhaps gave rise to fanciful legends concerning a queen who, ruling in her own right, conquered Egypt and part of Ethiopia, and invaded India with an army of more than a million of men. This mythical heroine ended her career by flying away in the form of a dove. It became customary to ascribe all buildings and other public works whose origin was unknown, to Semiramis; the date of her reign was fixed at about 2200 B. C.; and she was said to have been the wife of Ninus, an equally mythical person, the reputed founder of Nineveh.

31. Asshur-danin-il II was less warlike than his ancestors. The time of his reign is ascertained by an eclipse of the sun, which the inscriptions place in his ninth year, and which astronomers know to have occurred June 15, 763 B. C. After Asshur-likh-khus, the following king, the dynasty was ended with a revolution. Nabonas´sar, of Babylon, not only made himself independent, but gained a brief supremacy over Assyria. The Assyrians, during the Second Period, made great advances in literature and arts. The annals of each reign were either cut in stone or impressed upon a duplicate series of bricks, to guard against destruction either by fire or water. If fire destroyed the burnt bricks, it would only harden the dried; and if the latter were dissolved by water, the former would remain uninjured. Engraved columns were erected in all the countries under Assyrian rule.

32. Third Period, B. C. 745-625. Tiglath-pileser II was the founder of the New or Lower Assyrian Empire, which he established by active and successful warfare. He conquered Damascus, Samaria, Tyre, the Philistines, and the Arabians of the Sinaitic peninsula; carried away captives from the eastern and northern tribes of Israel, and took tribute from the king of Judah. (2 Kings xv: 29; xvi: 7-9.)[20] Shalmaneser IV conquered Phœnicia, but was defeated in a naval assault upon Tyre. His successor, Sargon, took Samaria, which had revolted, and carried its people captive to his newly conquered provinces of Media and Gauzanitis. He filled their places with Babylonians, whose king, Merodach-baladan, he had captured, B. C. 709. An interesting inscription of Sargon relates his reception of tribute from seven kings of Cyprus, “who have fixed their abode in the middle of the sea of the setting sun.” The city and palace of Khor´sabad´ were entirely the work of Sargon. The palace was covered with sculptures within and without; it was ornamented with enameled bricks, arranged in elegant and tasteful patterns, and was approached by noble flights of steps through splendid porticos. In this “palace of incomparable splendor, which he had built for the abode of his royalty,” are found Sargon’s own descriptions of the glories of his reign. “I imposed tribute on Pharaoh, of Egypt; on Tsamsi, Queen of Arabia; on Ithamar, the Sabæan, in gold, spices, horses, and camels.” Among the spoils of the Babylonian king, he enumerates his golden tiara, scepter, throne and parasol, and silver chariot. In the old age of Sargon, Merodach-baladan recovered his throne, and the Assyrian king was murdered in a conspiracy.

33. His son, Sennach´erib, reëstablished Assyrian power at the eastern and western extremities of his empire. He defeated Merodach-baladen, and placed first an Assyrian viceroy, and afterward his own son, Assarana´dius, upon the Babylonian throne. He quelled a revolt of the Phœnician cities, and extorted tribute from most of the kings in Syria. He gained a great battle at El´tekeh, in Palestine, against the kings of Egypt and Ethiopia, and captured all the “fenced cities of Judah.” (2 Kings xviii: 13.) In a second expedition against Palestine and Egypt, 185,000 of his soldiers were destroyed in a single night, near Pelusium, as a judgment for his impious boasting. (2 Kings xix: 35, 36.) On his return to Nineveh, two of his sons conspired against him and slew him, and E´sarhad´don, another son, obtained the crown. His reign (B. C. 680-667) was signalized by many conquests. He defeated Tir´hakeh, king of Egypt, and broke up his kingdom into petty states. He completed the colonization of Samaria with people from Babylonia, Susiana, and Persia. His royal residence was alternately at Nineveh and Babylon.

34. Under As´shur-ba´ni-pal, son of Esarhaddon, Assyria attained her greatest power and glory. He reconquered Egypt, which had rallied under Tirhakeh, overran Asia Minor, and imposed a tribute upon Gyges, king of Lydia. He subdued most of Armenia, reduced Susiana to a mere province of Babylonia, and exacted obedience from many Arabian tribes. He built the grandest of all the Assyrian[21] palaces, cultivated music and the arts, and established a sort of royal library at Nineveh.

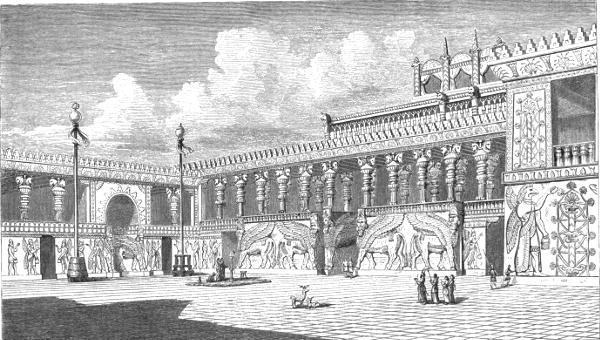

COURT OF SARGON’S PALACE, AT KHORSABAD.

35. The reign of his son, Asshur-emid-ilin, called Saracus by the Greeks, was overwhelmed with disasters. A horde of barbarians, from the plains of Scythia, invaded the empire, and before it could recover from the shock, it was rent by a double revolt of Media on the north, and Babylonia on the south. Nabopolassar, the Babylonian, had been general of the armies of Saracus; but finding himself stronger than his master, he made an alliance with Cyax´ares, king of the Medes, in concert with whom he besieged and captured Nineveh. The Assyrian monarch perished in the flames of his palace, and the two conquerors divided his dominions between them. Thus ended the Assyrian Empire, B. C. 625.

36. The Third Period was the Golden Age of Assyrian Art. The sculptured marbles which have been brought from the palaces of Sargon, Sennacherib, and Asshur-bani-pal, show a skill and genius in the carving which remind us of the Greeks. A few may be seen in collections of colleges and other learned societies in this country. The most magnificent specimens are in the British Museum, the Louvre at Paris, and the Oriental Museum at Berlin. During the same period the sciences of geography and astronomy were cultivated with great diligence; studies in language and history occupied multitudes of learned men; and modern scholars, as they decipher the long-buried memorials, are filled with admiration of the mental activity which characterized the times of the Lower Empire of Assyria.

For the First and more than half the Second Period, the names are discontinuous and dates unknown. We begin, therefore, with the era of ascertained chronology.

| Asshur-danin-il I | died | B. C. | 909. |

| Hu-likh-khus III | reigned | ” | 909-889. |

| Tiglathi-nin II | ” | ” | 889-886. |

| Asshur-nasir-pal I | ” | ” | 886-858. |

| Shalmaneser II | ” | ” | 858-823. |

| Shamas-iva | ” | ” | 823-810. |

| Hu-likh-khus IV | ” | ” | 810-781. |

| Shalmaneser III | ” | ” | 781-771. |

| Asshur-danin-il II | ” | ” | 771-753. |

| Asshur-likh-khus | ” | ” | 753-745. |

| Tiglath-pileser II, usurper,[7] | B. C. | 745-727. | |

| Shalmaneser IV, | ” | 727-721. | |

| Sargon, usurper, | ” | 721-705. | |

| Sennacherib, | ” | 705-680. | |

| Esarhaddon, | ” | 680-667. | |

| Asshur-bani-pal, | about | ” | 667-647. |

| Asshur-emid-ilin, | ” | 647-625. |

A kingdom of mighty hunters and great builders is founded by Nimrod, B. C. 2000. Chaldæa becomes subject, first to Arabian, then to Assyrian invaders, but is made independent by Pul, B. C. 772. The Assyrian monarchy absorbs the Chaldæan, and extends itself from Syria to the Persian mountains. After two hundred years’ depression, its records become authentic B. C. 909. Iva-lush and Sammuramit reign jointly over greatly increased territories. The Lower Empire is established by Tiglath-pileser II, whose dominion reaches the Mediterranean. Sargon records many conquests in his palace at Khorsabad. Sennacherib recaptures Babylon and gains victories over Egypt and Palestine. The Assyrian Empire is increased by Esarhaddon, and culminates under Asshur-bani-pal, only to be overthrown in the next reign by a Scythian invasion and a revolt of Media and Babylonia.

37. Little is known of the Medes before the invasion of their country by Shalmaneser II, B. C. 830, and its partial conquest by Sargon,[8] in 710. They had some importance, however, in the earliest times after the Deluge, for Berosus tells us that a Median dynasty governed Babylon during that period. The country was doubtless divided among petty chieftains, whose rivalries prevented its becoming great or famous in the view of foreign nations.

In Babylonian names, Nebo, Merodach, Bel, and Nergal correspond to Asshur, Sin, and Shamas in Assyrian. Thus, Abed-nego (for Nebo) is the “Servant of Nebo;” Nebuchadnezzar means “Nebo protect my race,” or “Nebo is the protector of landmarks;” Nabopolassar = “Nebo protect my son”—the exact equivalent of Asshur-nasir-pal in the Assyrian Dynasty of the Second Period.

38. About 740 B. C., according to Herodotus, the Medes revolted from Assyria, and chose for their king Dei´oces, whose integrity as a judge had marked him as fittest for supreme command. He built the city of Ecbat´ana, which he fortified with seven concentric circles of stone, the innermost being gilded so that its battlements shone like gold. Here Deioces established a severely ceremonious etiquette, making up for his want of hereditary rank by all the external tokens of the divinity that “doth hedge a king.” No courtier was permitted to laugh in his presence, or to approach him without the profoundest expressions of reverence. Either his real dignity of character or these stately ceremonials had such effect, that he enjoyed a prosperous reign of fifty-three years. Though Deioces is described by Herodotus as King of the Medes, it is probable that he was ruler only of a single tribe, and that a great part of his story is merely imaginary.

39. The true history of the Median kingdom dates from B. C. 650, when Phraor´tes was on the throne. This king, who is called the son of Deioces, extended his authority over the Persians, and formed that close connection of the Medo-Persian tribes which was never to be dissolved. The supremacy was soon gained by the latter nation. The double kingdom was seen by Daniel in his vision, under the form of a ram, one of whose horns was higher than the other, and “the higher came up last.” (Daniel viii: 3, 20.) Phraor´tes, reinforced by the Persians, made many conquests in Upper Asia. He was killed in a war against the last king of Assyria, B. C. 633.

40. Determined to avenge his father’s death, Cyaxares renewed the war with Assyria. He was called off to resist a most formidable incursion of barbarians from the north of the Caucasus. These Scythians became masters of Western Asia, and their insolent dominion is said to have lasted twenty-eight years. A band of the nomads were received into the service of Cyaxares as huntsmen. According to Herodotus, they returned one day empty-handed from the chase; and upon the king’s expressing his displeasure, their ferocious temper burst all bounds. They served up to him, instead of game, the flesh of one of the Median boys who had been placed with them to learn their language and the use of the bow, and then fled to the court of the King of Lydia. This circumstance led to a war between Alyat´tes and Cyaxares, which continued five years without any decisive result. It was terminated by an eclipse of the sun occurring in the midst of a battle. The two kings hastened to make peace; and the treaty, which fixed the boundary of their two empires at the River Halys, was confirmed by the marriage of the son of Cyaxares with the daughter of Alyattes. The Scythian oppressions were ended by a general massacre of the barbarians, who, by a secretly concerted plan, had been invited to banquets and made drunken with wine.

41. Cyaxares now resumed his plans against Assyria. In alliance with Nabopolassar, of Babylon, he was able to capture Nineveh, overthrow the empire, and render Media a leading power in Asia. The successful wars of Cyaxares secured for himself and his son nearly half a century of peace, during which the Medes rapidly adopted the luxurious habits of the nations they had conquered. The court of Ecbatana became as magnificent as that of Nineveh had been when at the height of its grandeur. The courtiers delighted in silken garments of scarlet and purple, with collars and bracelets of gold, and the same precious metal adorned the harness of their horses. Reminiscences of the old barbaric life remained in an excessive fondness for hunting, which was indulged either in the parks about the capital, or in the open country, where lions, leopards, bears, wild boars, stags, and antelopes still abounded. The great wooden palace, covered with plates of gold and silver, as well as other buildings of the capital, showed a barbarous fondness for costly materials, rather than grandeur of architectural ideas. The Magi, a priestly caste, had great influence in the Median court. The education of each young king was confided to them, and they continued throughout his life to be his most confidential counselors.

42. B. C. 593. Cyaxares died after a reign of forty years. His son, Asty´ages, reigned thirty-five years in friendly and peaceful alliance with the kings of Lydia and Babylon. Little is known of him except the events connected with his fall, and these will be found related in the history of Cyrus, Book II.

| Phraortes | died | B. C. | 633. |

| Cyaxares | reigned | ” | 633-593. |

| Astyages | ” | ” | 593-558. |

Note.—It is impossible to reconcile the chronology of the reign of Cyaxares with all the ancient accounts. If the Scythian invasion occurred after the beginning of his reign, continued twenty-eight years, and ended before the Fall of Nineveh, it is easy to see that the date of the latter event must have been later than is given in the text. The French school of Orientalists place it, in fact, B. C. 606, and the accession of Cyaxares in 634. The English school, with Sir H. Rawlinson at their head, give the dates which we have adopted.

43. For nearly five hundred years, Babylon had been governed by Assyrian viceroys, when Nabonassar (747 B. C.) threw off the yoke, and established an independent kingdom. He destroyed the humiliating records of former servitude, and began a new era from which Babylonian time was afterward reckoned.

44. Merodach-baladan, the fifth king of this line, sent an embassy to Hezekiah, king of Judah, to congratulate him upon his recovery from illness, and to inquire concerning an extraordinary phenomenon connected with his restoration. (Isaiah xxxviii: 7, 8; xxxix: 1.) This shows that the Babylonians were no less alert for astronomical observations than their predecessors, the Chaldæans. In fact, the brilliant clearness of their heavens early led the inhabitants of this region to a study of the stars. The sky was mapped out in constellations, and the fixed stars were catalogued; time was measured by sun-dials, and other astronomical instruments were invented by the Babylonians.

45. The same Merodach-baladan was taken captive by Sargon, king of Assyria, and held for six years, while an Assyrian viceroy occupied his throne. He escaped and resumed his government, but was again dethroned by Sennacherib, son of Sargon. The kingdom remained in a troubled state, usually ruled by Assyrians, but seeking independence, until Esarhaddon, son of Sennacherib, conquered Babylon, built himself a palace, and reigned alternately at that city and at Nineveh. His son, Sa´os-duchi´nus, governed Babylon as viceroy for twenty years, and was succeeded by Cinnelada´nus, another Assyrian, who ruled twenty-two years.

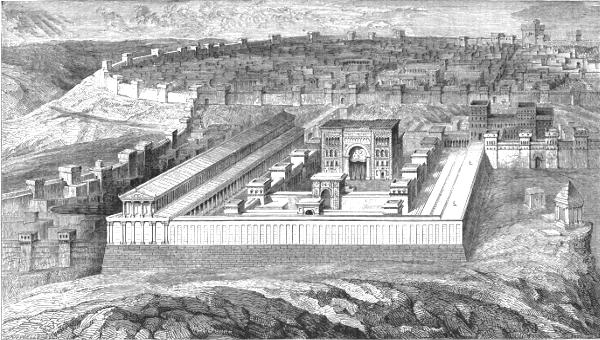

46. B. C. 625. Second Period. Nabopolas´sar, a Babylonian general, took occasion, from the misfortunes of the Assyrian Empire, to end the long subjection of his people. He allied himself with Cyaxares, the Median king, to besiege Nineveh and overthrow the empire. In the subsequent division of spoils, he received Susiana, the Euphrates Valley, and the whole of Syria, and erected a new empire, whose history is among the most brilliant of ancient times. The extension of his dominions westward brought him in collision with a powerful neighbor, Pha´raoh-ne´choh, of Egypt, who actually subdued the Syrian provinces, and held them a few years. But Nabopolassar sent his still more powerful son, Nebuchadnez´zar, who chastised the Egyptian king in the battle of Car´chemish, and wrested from him the stolen provinces. He also besieged Jerusalem, and returned to Babylon laden with the treasures of the temple and palace of Solomon. He brought in his train Jehoi´akim, king of Judah, and several young persons of the royal family, among whom was the prophet Daniel.

47. During his son’s campaign, Nabopolassar had died at Babylon, and the victorious prince was immediately acknowledged as king. Nebuchadnezzar made subsequent wars in Phœnicia, Palestine, and Egypt, and established an empire which extended westward to the Mediterranean Sea. He deposed the king of Egypt, and placed Amasis upon the throne as his deputy. Zedeki´ah, who had been elevated[26] to the throne of Judah, rebelled against Babylon, and Nebuchadnezzar set out in person to punish his treachery. He besieged Jerusalem eighteen months, and captured Zedekiah, who, with true Eastern cruelty, was compelled to see his two sons murdered before his eyes were put out, and he was carried in chains to Babylon. In a later war, Nebuzar-adan, general of the armies of Nebuchadnezzar, destroyed Jerusalem, burned the temple and palaces, and carried the remnant of the people to Babylon. The strong and wealthy city of Tyre revolted, and resisted for thirteen years the power of the great king, but at length submitted, and all Phœnicia remained under the Babylonian yoke, B. C. 585.

48. The active mind of Nebuchadnezzar, absorbed in schemes of conquest, began to be visited by dreams, in one of which the series of great empires which were yet to arise in the east was distinctly foreshadowed. Of all the wise men of the court, Daniel alone was enabled to interpret the vision; and his spiritual insight, together with the singular elevation and purity of his character, gained him the affectionate confidence of the king. (Read Daniel ii.)

49. The reign of Nebuchadnezzar was illustrated by grand public works. His wife, a Median princess, sighed for her native mountains, and was disgusted with the flatness of the Babylonian plain, the greatest in the ancient world. To gratify her, the elevated—rather than “hanging”—gardens were created. Arches were raised on arches in continuous series until they overtopped the walls of Babylon, and stairways led from terrace to terrace. The whole structure of masonry was overlaid with soil sufficient to nourish the largest trees, which, by means of hydraulic engines, were supplied from the river with abundant moisture. In the midst of these groves stood the royal winter residence; for a retreat, which in other climates would be most suitable for a summer habitation, was here reserved for those cooler months in which alone man can live in the open air. This first great work of landscape gardening which history describes, comprised a charming variety of hills and forests, rivers, cascades, and fountains, and was adorned with the loveliest flowers the East could afford.

50. The same king surrounded the city with walls of burnt brick, two hundred cubits high and fifty in thickness, which, together with the gardens, were reckoned among the Seven Wonders of the World. During his reign and that of his son-in-law, Nabona´dius, the whole country was enriched by works of public utility: canals, reservoirs, and sluices were multiplied, and the shores of the Persian Gulf were improved by means of piers and embankments.

51. Owing to these encouragements, as well as to her fortunate position midway between the Indus and the Mediterranean, with the Gulf and the two great rivers for natural highways, Babylon was thronged with the merchants of all nations, and her commerce embraced the known world.[27] Manufactures, also, were numerous and famous. The cotton fabrics of the towns on the Tigris and Euphrates were unsurpassed for fineness of quality and brilliancy of color; and carpets, which were in great demand among the luxurious Orientals, were nowhere produced in such magnificence as in the looms of Babylon.

52. It is not strange that the pride of Nebuchadnezzar was kindled by the magnificence of his capital. As he walked upon the summit of his new palace, and looked down upon the swarming multitudes who owed their prosperity to his protection and fostering care, he said, “Is not this great Babylon, that I have built for the house of the kingdom by the might of my power, and for the honor of my majesty?” At that moment the humiliation foretold in a previous dream, interpreted by Daniel, came upon him. We can not better describe the manner of the judgment than in the king’s own words (Daniel iv: 31-37):

“While the word was in the king’s mouth, there fell a voice from heaven, saying, O King Nebuchadnezzar, to thee it is spoken; The kingdom is departed from thee. And they shall drive thee from men, and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field: they shall make thee to eat grass as oxen, and seven times shall pass over thee, until thou know that the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will. The same hour was the thing fulfilled upon Nebuchadnezzar: and he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws. And at the end of the days, I, Nebuchadnezzar, lifted up mine eyes unto heaven, and mine understanding returned unto me, and I blessed the Most High, and I praised and honored him that liveth forever, whose dominion is an everlasting dominion, and his kingdom is from generation to generation.… At the same time my reason returned unto me; and for the glory of my kingdom, mine honor and brightness returned unto me; and my counselors and my lords sought unto me; and I was established in my kingdom, and excellent majesty was added unto me. Now I, Nebuchadnezzar, praise and extol and honor the King of heaven, all whose works are truth, and his ways judgment: and those that walk in pride he is able to abase.”

53. The immediate successors of Nebuchadnezzar were not his equals in character or talent. Evil-merodach, his son, was murdered after a reign of two years by Nereglis´sar, his sister’s husband. This prince was advanced in years when he ascended the throne, having been already a chief officer of the crown thirty years before at the siege of Jerusalem. He reigned but four years, and was succeeded by his son, La´borosoar´chod. The young king was murdered, after only nine months’ reign, by Nabona´dius, who became the last king of Babylon. The usurper strengthened his title by marrying a[28] daughter of Nebuchadnezzar—probably the widow of Nereglissar—and afterward by associating their son Belshaz´zar with him in the government. He also sought security in foreign alliances. He fortified his capital by river walls, and constructed water-works in connection with the river above the city, by which the whole plain north and west could be flooded to prevent the approach of an enemy.

54. A new power was indeed arising in the East, against which the three older but feebler monarchies, Babylonia, Lydia, and Egypt, found it necessary to combine their forces. After the conquest of Lydia, and the extension of the Persian Empire to the Ægean Sea, Nabonadius had still fifteen years for preparation. He improved the time by laying up enormous quantities of food in Babylon; and felt confident that, though the country might be overrun, the strong walls of Nebuchadnezzar would enable him cheerfully to defy his foe. On the approach of Cyrus he resolved to risk one battle; but in this he was defeated, and compelled to take refuge in Bor´sippa. His son Belshazzar, being left in Babylon, indulged in a false assurance of safety. Cyrus, by diverting the course of the Euphrates, opened a way for his army into the heart of the city, and the court was surprised in the midst of a drunken revel, unprepared for resistance. The young prince, unrecognized in the confusion, was slain at the gate of his palace. Nabonadius, broken by the loss of his capital and his son, surrendered himself a prisoner; and the dominion of the East passed to the Medo-Persian race. Babylon became the second city of the empire, and the Persian court resided there the greater portion of the year.

Deioces, the first reputed king of Media, built and adorned Ecbatana. Phraortes united the Medes and Persians into one powerful kingdom. In the reign of Cyaxares, the Scythians ruled Western Asia twenty-eight years. After their expulsion, Cyaxares, in alliance with the Babylonian viceroy, overthrew the Assyrian Empire, divided its territories with his ally, and raised his own dominion to a high degree of wealth. His son Astyages reigned peacefully thirty-five years.

Babylon, under Nabonassar, became independent of Assyria, B. C. 747. Merodach-baladan, the fifth native king, was twice deposed, by Sargon and Sennacherib, and the country again remained forty-two years under Assyrian rule. It was delivered by Nabopolassar, whose still more powerful son, Nebuchadnezzar, gained great victories over the kings of Judah and Egypt, replacing the latter with viceroys of his own, and transporting the former, with the princes, nobles, and sacred treasures of Jerusalem, to Babylon. By a thirteen years’ siege, Tyre was subdued and all Phœnicia conquered. From visions interpreted by Daniel, Nebuchadnezzar learned the future rise and fall of Asiatic empires. He constructed the Hanging Gardens, the walls of Babylon, and many other public works. His pride was punished by seven years’ degradation. Evil-merodach was murdered by Nereglissar, who after four years bequeathed his crown to Laborosoarchod. Nabonadius obtained the throne by violence, and in concert with his son Belshazzar, tried to protect his dominions against Cyrus; but Babylon was taken and the empire overthrown, B. C. 538.

55. The Anatolian peninsula, divided by its mountain chains into several sections, was occupied from very ancient times by different nations nearly equal in power. Of these, the Phrygians were probably the earliest settlers, and at one time occupied the whole peninsula. Successive immigrations from the east and west pressed them inward from the coast, but they still had the advantage of a large and fertile territory. They were a brave but rather brutal race, chiefly occupied with agriculture, and especially the raising of the vine.

56. The Phrygians came from the mountains of Armenia, whence they brought a tradition of the Flood, and of the resting of the ark on Mount Ararat. They were accustomed, in primitive times, to hollow their habitations out of the rock of the Anatolian hills, and many of these rock cities may be found in all parts of Asia Minor. Before the time of Homer, however, they had well-built towns and a flourishing commerce.

57. Their religion consisted of many dark and mysterious rites, some of which were afterward copied by the Greeks. The worship of Cyb´ele, and of Saba´zius, god of the vine, was accompanied by the wildest music and dances. The capital of Phrygia was Gor´dium, on the Sanga´rius. The kings were alternately called Gor´dias and Mi´das, but we have no chronological lists. Phrygia became a province of Lydia B. C. 560.

58. In later times Lydia became the greatest kingdom in Asia Minor, both in wealth and power, absorbing in its dominion the whole peninsula, except Lycia, Cilicia, and Cappadocia. Three dynasties successively bore rule: the Atyadæ, before 1200 B. C.; the Heraclidæ, for the next 505 years; and the Mermnadæ, from B. C. 694 until 546, when Crœsus, the last and greatest monarch, was conquered by the Persians. The name of this king has become proverbial from his enormous wealth. When associated with his father as crown prince, he was visited by Solon of Athens, who looked on all the splendor of the court with the coolness of a philosopher. Annoyed by his indifference, the prince asked Solon who, of all the men he had encountered in his travels, seemed to him the happiest. To his astonishment, the wise man named two persons in comparatively humble stations, but the one of whom was blessed with dutiful children, and the other had died a triumphant and glorious death. The vanity of Crœsus could no longer abstain from a direct effort to extort a compliment. He asked if Solon did not consider him a happy man. The philosopher gravely replied that, such were the vicissitudes of life, no man, in his opinion, could safely be pronounced happy until his life was ended.

59. Crœsus extended his power over not only the whole Anatolian peninsula, but the Greek islands both of the Ægean and Ionian seas. He made an alliance with Sparta, Egypt, and Babylon to resist the growing[30] empire of Cyrus; but his precautions were ineffectual; he was defeated and made prisoner. He is said to have been bound upon a funeral pile, or altar, near the gate of his capital, when he recalled with anguish of heart the words of the Athenian sage, and three times uttered his name, “Solon, Solon, Solon!” Cyrus, who was regarding the scene with curiosity, ordered his interpreters to inquire what god or man he had thus invoked in his distress. The captive king replied that it was the name of a man with whom he wished that every monarch might be acquainted; and described the visit and conversation of the serene philosopher who had remained undazzled by his splendor. The conqueror was inspired with a more generous emotion by the remembrance that he, too, was mortal; he caused Crœsus to be released and to dwell with him as a friend.

Of the First and Second Dynasties, the names are only partially known, and dates are wanting.

| Atyadæ | Heraclidæ, last six: |

Mermnadæ: | ||

| Manes, | Adyattes I, | Gyges, | B. C. | 694-678. |

| Atys, | Ardys, | Ardys, | ” | 678-629. |

| Lydus, | Adyattes II, | Sadyattes, | ” | 629-617. |

| Meles, | Meles, | Alyattes, | ” | 617-560. |

| Myrsus, | Crœsus, | ” | 560-546. | |

| Candaules. | ||||

60. The small strip of land between Mount Lebanon and the sea was more important to the ancient world than its size would indicate. Here arose the first great commercial cities, and Phœnician vessels wove a web of peaceful intercourse between the nations of Asia, Africa, and Europe.

61. Sidon was probably the most ancient, and until B. C. 1050, the most flourishing, of all the Phœnician communities. About that year the Philistines of Askalon gained a victory over Sidon, and the exiled inhabitants took refuge in the rival city of Tyre. Henceforth the daughter surpassed the mother in wealth and power. When Herodotus visited Tyre, he found a temple of Hercules which claimed to be 2,300 years old. This would give Tyre an antiquity of 2,750 years B. C.

62. Other chief cities of Phœnicia were Bery´tus (Beirût), Byb´lus, Tri´polis, and Ara´dus. Each with its surrounding territory made an independent state. Occasionally in times of danger they formed themselves into a league, under the direction of the most powerful; but the[31] name Phœnicia applies merely to territory, not to a single well organized state, nor even to a permanent confederacy. Each city was ruled by its king, but a strong priestly influence and a powerful aristocracy, either of birth or wealth, restrained the despotic inclinations of the monarch.

63. The commerce of the Phœnician cities had no rival in the earlier centuries of their prosperity. Their trading stations sprang up rapidly along the coasts and upon the islands of the Mediterranean; and even beyond the Pillars of Hercules, their city of Gades (Kadesh), the modern Cadiz, looked out upon the Atlantic. These remote colonies were only starting points from which voyages were made into still more distant regions. Merchantmen from Cadiz explored the western coasts of Africa and Europe. From the stations on the Red Sea, trading vessels were fitted out for India and Ceylon.

64. At a later period, the Greeks absorbed the commerce of the Euxine and the Ægean, while Carthage claimed her share in the Western Mediterranean and the Atlantic. By this time, however, Western Asia was more tranquil under the later Assyrian and Babylonian monarchs; and the wealth of Babylon attracted merchant trains from Tyre across the Syrian Desert by way of Tadmor. Other caravans moved northward, and exchanged the products of Phœnician industry for the horses, mules, slaves, and copper utensils of Armenia and Cappadocia. A friendly intercourse was always maintained with Jerusalem, and a land-traffic with the Red Sea, which was frequented by Phœnician fleets. Gold from Ophir, pearls and diamonds from Eastern India and Ceylon, silver from Spain, linen embroidery from Egypt, apes from Western Africa, tin from the British Isles, and amber from the Baltic, might be found in the cargoes of Tyrian vessels.

65. The Phœnicians in general were merchants, rather than manufacturers; but their bronzes and vessels in gold and silver, as well as other works in metal, had a high repute. They claimed the invention of glass, which they manufactured into many articles of use and ornament. But the most famous of their products was the “Tyrian purple,” which they obtained in minute drops from the two shell-fish, the buccinum and murex, and by means of which they gave a high value to their fabrics of wool.

66. About the time of Pygma´lion, the warlike expeditions of Shalmaneser II overpowered the Phœnician towns, and for more than two hundred years they remained tributary to the Assyrian Empire. Frequent but usually vain attempts were made, during the latter half of this period, to throw off the yoke. With the fall of Nineveh it is probable that Phœnicia became independent.

67. B. C. 608. It was soon reduced, however, by Necho of Egypt, who added all Syria to his dominions, and held Phœnicia dependent until he himself was conquered by Nebuchadnezzar (B. C. 605) at Carchemish.[32] The captive cities were only transferred to a new master; but, in 598, Tyre revolted against the Babylonian, and sustained a siege of thirteen years. When at length she was compelled to submit, the conqueror found no plunder to reward the extreme severity of his labors, for the inhabitants had secretly removed their treasures to an island half a mile distant, where New Tyre soon excelled the splendor of the Old.

68. Phœnicia remained subject to Babylon until that power was overcome by the new empire of Cyrus the Great. The local government was carried on by native kings or judges, who paid tribute to the Babylonian king.

69. The religion of the Phœnicians was degraded by many cruel and uncleanly rites. Their chief divinities, Baal and Astar´te, or Ashtaroth, represented the sun and moon. Baal was worshiped in groves on high places, sometimes, like the Ammonian Moloch, with burnt-offerings of human beings; always with wild, fanatical rites, his votaries crying aloud and cutting themselves with knives. Melcarth, the Tyrian Hercules, was worshiped only at Tyre and her colonies. His symbol was an ever-burning fire, and he probably shared with Baal the character of a sun-god. The marine deities were of especial importance to these commercial cities. Chief of these were Posi´don, Ne´reus, and Pontus. Of lower rank, but not less constantly remembered, were the little Cabi´ri, whose images formed the figure-heads of Phœnician ships. The seat of their worship was at Berytus.

70. The Phœnicians were less idolatrous than the Egyptians, Greeks, or Romans; for their temples contained either no visible image of their deities, or only a rude symbol like the conical stone which was held to represent Astarte.

| Abibaal, partly contemporary with David in Israel. | ||

| Hiram, his son, friend of David and Solomon, | B. C. | 1025-991. |

| Balea´zar, | ” | 991-984. |

| Abdastar´tus, | ” | 984-975. |

| One of his assassins, whose name is unknown, | ” | 975-963. |

| Astartus, | ” | 963-951. |

| Aser´ymus, his brother, | ” | 951-942. |

| Phales, another brother, who murdered Aserymus, | ” | 942-941. |

| Ethba´al,[9] high priest of Astarte, | ” | 941-909. |

| [33]Bade´zor, his son, | ” | 909-903. |

| Matgen, son of Badezor and father of Dido, | ” | 903-871. |

| Pygmalion, brother of Dido, | ” | 871-824. |

For 227 years Tyre remained tributary to the Eastern Monarchies, and we have no list of her native rulers.

| Ethbaal II, contemporary with Nebuchadnezzar, | B. C. | 597-573. |

| Baal, | ” | 573-563. |

| Ec´niba´al, judge for three months, | ” | 563. |

| Chel´bes, judge ten months, | ” | 563-562. |

| Abba´rus, judge three months, | ” | 562. |

| Mytgon and Gerastar´tus, judges five years, | ” | 562-557. |

| Bala´tor, king, | ” | 557-556. |

| Merbal, king, | ” | 556-552. |

| Hiram, king, | ” | 552-532. |

71. Syria Proper was divided between several states, of which the most important in ancient times was Damascus, with its territory, a fertile country between Anti-Lebanon and the Syrian Desert. Beside this were the northern Hittites, whose chief city was Carchemish; the southern Hittites, in the region of the Dead Sea; the Pate´na on the lower, and Hamath on the upper Orontes.

72. Damascus, on the Abana, is among the oldest cities in the world. It resisted the conquering arms of David and Solomon, who, with this exception, reigned over all the land between the Jordan and the Euphrates; and it continued to be a hostile and formidable neighbor to the Hebrew monarchy, until Jews, Israelites, and Syrians were all alike overwhelmed by the growth of the Assyrian Empire.

| Hadad, | contemporary with | David, | about B. C. | 1040. |

| Rezon, | ” | Solomon, | ” | 1000. |

| Tab-rimmon, | ” | Abijah, | ” | 960-950. |

| Ben-hadad I, | ” | Baasha and Asa, | ” | 950-920. |

| Ben-hadad II, | ” | Ahab, | ” | 900. |

| Hazael, | ” | Jehu and Shalmaneser II, | ” | 850. |

| Ben-hadad III, | ” | Jehoahaz, | ” | 840. |

| Unknown until Rezin, | ” | Ahaz of Judah, | ” | 745-732. |

73. The history of the Hebrew race is better known to us than that of any other people equally ancient, because it has been carefully preserved in the sacred writings. The separation of this race for its peculiar and important part in the world’s history, began with the call of Abraham from his home, near the Euphrates, to the more western country on the Mediterranean, which was promised to himself and his descendants. The story of his sons and grandsons, before and during their residence in Egypt, belongs, however, to family rather than national history. Their numbers increased until they became objects of apprehension to the Egyptians, who tried to break their spirit by servitude. At length, Moses grew up under the fostering care of Pharaoh himself; and after a forty years’ retirement in the deserts of Midian, adding the dignity of age and lonely meditation to the “learning of the Egyptians,” he became the liberator and law-giver of his people.

74. The history of the Jewish nation begins with the night of their exodus from Egypt. The people were mustered according to their tribes, which bore the names of the twelve sons of Jacob, the grandson of Abraham. The sons of Joseph, however, received each a portion and gave their names to the two tribes of Ephraim and Manas´seh. The family of Jacob went into Egypt numbering sixty-seven persons; it went out numbering 603,550 warriors, not counting the Levites, who were exempted from military duty that they might have charge of the tabernacle and the vessels used in worship.

75. After long marches and countermarches through the Arabian desert—needful to arouse the spirit of a free people from the cowed and groveling habits of the slave, as well as to counteract the long example of idolatry by direct Divine revelation of a pure and spiritual worship—the Israelites were led into the land promised to Abraham, which lay chiefly between the Jordan and the sea. Two and a half of the twelve tribes—Reuben, Gad, and the half tribe of Manasseh—preferred the fertile pastures east of the Jordan; and on condition of aiding their brethren in the conquest of their more westerly territory, received their allotted portion there.

76. Moses, their great leader through the desert, died outside the Promised Land, and was buried in the land of Moab. His lieutenant, Joshua, conquered Palestine and divided it among the tribes. The inhabitants of Gibeon hastened to make peace with the invaders by a stratagem. Though their falsehood was soon discovered, Joshua was faithful to his oath already taken, and the Gibeonites escaped the usual fate of extermination pronounced upon the inhabitants of Canaan, by becoming servants and tributaries to the Hebrews.

77. The kings of Palestine now assembled their forces to besiege the traitor city, in revenge for its alliance with the strangers. Joshua hastened to its assistance, and in the great battle of Beth-horon defeated, routed, and destroyed the armies of the five kings. This conflict decided the possession of central and southern Palestine. Jabin, “king of Canaan,” still made a stand in his fortress of Hazor, in the north. The conquered kings had probably been in some degree dependent on him as their superior, if not their sovereign. He now mustered all the tribes which had not fallen under the sword of the Israelites, and encountered Joshua at the waters of Merom. The Canaanites had horses and chariots; the Hebrews were on foot, but their victory was as complete and decisive as at Beth-horon. Hazor was taken and burnt, and its king beheaded.

78. The nomads of the forty years in the desert now became a settled, civilized, and agricultural people. Shiloh was the first permanent sanctuary; there the tabernacle constructed in the desert was set up, and became the shrine of the national worship.

79. Jewish History is properly divided into three periods:

| I. | From the Exodus to the establishment of the Monarchy, | B. C. 1650-1095. | (See Note, page 47.) |

| II. | From the accession of Saul to the separation into two kingdoms, | B. C. 1095-975. | |

| III. | From the separation of the kingdoms to the Captivity at Babylon, | B. C. 975-586. |

80. During the First Period the government of the Hebrews was a simple theocracy, direction for all important movements being received through the high priest from God himself. The rulers, from Moses down, claimed no honors of royalty, but led the nation in war and judged it in peace by general consent. They were designated to their office at once by revelation from heaven, and by some special fitness in character or person which was readily perceived. Thus the zeal and courage of Gideon, the lofty spirit of Deb´orah, the strength of Samson, rendered them most fit for command in the special emergencies at which they arose. The “Judge” usually appeared at some time of danger or calamity, when the people would gladly welcome any deliverer; and his power, once conferred, lasted during his life.

After his death a long interval usually occurred, during which “every man did that which was right in his own eyes,” until a new invasion by Philis´tines, Ammonites, or Zidonians called for a new leader. The chronology of this period is very uncertain, as the sacred writers only incidentally mention the time of events, and their records are not always continuous. The system of chronology was not settled until a later period.

| Moses, liberator, law-giver, and judge, | 40 | years |

| Joshua, conqueror of Palestine, and judge, | 25 | ” |

| Anarchy, idolatry, submission to foreign rulers, | 20 or 30 | ” |

| Servitude under Chushan-rishathaim of Mesopotamia, | 8 | ” |

| Othniel, deliverer and judge, | 40 | ” |

| Servitude under Eglon, king of Moab, | 18 | ” |

| {Ehud, | ||

| {Shamgar. In these two reigns the land has rest, | 80 | ” |

| Servitude under Jabin, king of Canaan, | 20 | ” |

| Deborah, | 40 | ” |