DREADNOUGHTS OF THE DOGGER

DREADNOUGHTS

OF THE DOGGER

A Story of the War on the

North Sea

BY

ROBERT LEIGHTON

Author of "The Golden Galleon," "The Thirsty Sword," etc.

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON AND MELBOURNE

1916

Made and printed in Great Britain by

WARD, LOCK & Co., LIMITED, LONDON.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I.—WHAT'S BRED IN THE BONE

II.—THE PERIL OF THE SILVER PIT

III.—WATCHERS OF THE SEA

IV.—THE MENACE OF THE MINES

V.—UNDER THE SYCAMORE

VI.—WHAT MARK FOUND IN THE PIGEON LOFT

VII.—UNDER THE WHITE ENSIGN

VIII.—HOW MARK MADE HIMSELF SMALL

IX.—AN EXPERT IN MINE-SWEEPING

X.—DARBY CATCHPOLE'S DISCOVERY

XI.—THE ESCAPE

XII.—A FLEET IN HIDING

XIII.—THE GERMAN ADMIRAL

XIV.—BRAVE AS A BRITON

XV.—TREASURE TROVE

XVI.—THE BOMB-PROOF SHELTER

XVII.—TOLD THROUGH THE TELEPHONE

XVIII.—A SHRIMPING ADVENTURE

XIX.—U50

XX.—PUT TO THE TEST

XXI.—THE RAIDERS

XXII.—CUT AND RUN

XXIII.—STRIKING THE BALANCE

XXIV.—THE MEETING ON THE CLIFF

XXV.—MAX HILLIGER'S SATISFACTION

XXVI.—THE GUIDING LIGHT

XXVII.—SURVIVORS

XXVIII.—THE WAY TO CALAIS

XXIX.—MAX MEETS THE ADMIRAL

XXX.—DREADNOUGHT AGAINST DREADNOUGHT

XXXI.—SUBMARINES AT WORK

XXXII.—U50'S WORST CRIME

XXXIII.—MAX RENOUNCES THE FATHERLAND

XXXIV.—THE SUPPLY SHIP

XXXV.—PRISONERS OF WAR

DREADNOUGHTS OF

THE DOGGER.

CHAPTER I.

WHAT'S BRED IN THE BONE.

The Scoutmaster paused in his work of opening a tin of condensed milk on the top of a packing-case. Glancing upwards to the shoulder of the cliff, he caught sight of a figure partly concealed beyond a dark clump of gorse and bramble. He could see the shining brass tube of a telescope beneath a naval cap. The telescope was levelled at the slate-grey shape of a light cruiser riding at anchor in Haddisport Roads, abreast of the camp.

"Your brother's out early, Redisham," said the Scoutmaster, turning again to the milk tin. "I hope he'll come down to us. I expect he can tell us a lot about that cruiser out there. He looks well in his cadet's uniform!"

Mark Redisham was bending over the fire, frying eggs and bacon. Some of his companions were in the tent, dressing after their morning swim, while others of the patrol were variously occupied in preparing the camp breakfast.

"Yes, sir," he answered. "Lucky chap, isn't he? I envy him being in the navy. And he's more than a cadet now, Mr. Bilverstone. He's a full-fledged midshipman—or soon will be, when he steps aboard his ship."

One of the Sea Scouts near to him, a tall, loose-limbed youth with a budding moustache, stood watching the lithe young fellow in naval uniform, now approaching with his telescope under his arm.

"Lucky?" he repeated with a sneer. "I don't see where the luck comes in. I don't envy him."

"Indeed!" said Mark. "You don't envy a chap who is going to be an officer in the British Navy? Why? Oh, but I was forgetting——"

Most of the Sea Scouts in the Lion Patrol were in the habit of overlooking the fact that Max Hilliger was not British. He had been amongst them so long, first as a playfellow, then as a Scout, that they had almost come to think of him as a native of Haddisport. In reality, he was a German, his father, Heinrich Hilliger, being German Vice-Consul in the port, as well as a wealthy fish merchant, doing a big business with Germany.

"Why?" Max repeated, shrugging his shoulders. "It isn't good enough. You fellows are always boasting about your British Navy, as if it were the only fleet on the seas. You seem to forget that Germany has a navy as good, if not better." He laughed derisively. "You'll discover your mistake if Germany and England come to grips. Your boasted navy'll be licked into a cocked hat. Half your cruisers are only fit to be scrapped. Those that are not obsolete couldn't hold their own against the Kaiser's High Sea Fleet."

Here a diversion was caused by the arrival of Midshipman Rodney Redisham, who shook hands with Mr. Bilverstone, and nodded recognition to such of the patrol as he remembered.

"You've grown, Catchpole," he said to one, "and you, too, Quester. Hullo, Max, you here? You've changed since we met last."

"Max has just been arguing that the Kaiser's Fleet is better than ours," remarked the Scout master.

"Germany has some jolly good fighting ships," acknowledged the midshipman; "but I believe our guns have a longer range, and, of course, we've got more ships."

Max Hilliger seemed disposed to dispute the point, but at that moment there came to the sharp ears of the Scouts a peculiar buzzing sound from beyond the houses on the cliff. All eyes were turned expectantly skyward in the one direction. Presently an aeroplane appeared above the trees, and, sinking rapidly, skimmed the level ground of the denes, and alighted like a great bird on a patch of grass within fifty yards of the camp.

At a word from Mr. Bilverstone, two of the Scouts ran forward; but they had hardly reached the machine before the pilot had leapt to his feet.

"Don't handle anything, boys," he said, pushing his goggles up over his forehead. "She's all right. But I see there's a crowd of people on the cliff. They'll be coming down to nose around. Keep guard here, while I step along to your camp and get some warmth into me."

Rodney Redisham strode forward to meet him, and, seeing the two gold stripes on his sleeve, greeted him with a very formal naval salute.

"Why, it's Lieutenant Aldiss!" he cried. "Where have you come from, sir?"

"Dover," returned the officer. "And what are you doing here? Why aren't you in your ship? Any news?"

"News?" Redisham repeated. "Do you mean about the ultimatum to Germany?"

"Yes, of course. Is it to be war?"

"I don't know. It looks precious like it. But we haven't heard yet."

"It's beastly cold up there this morning," said the lieutenant, indicating the sky. "Have these Scouts got any hot coffee? Ah, I see one of them is fetching some. That's nice."

"But won't you come up to my home and have a proper breakfast, sir?" Rodney invited. "It's that red house with the tower, on the cliff."

Lieutenant Aldiss shook his head.

"Thank you, but I'm due at Buremouth at eight o'clock," he explained, and, taking the steaming cup which Max Hilliger had brought to him, he added: "So you're appointed to the Atreus, out there, are you?"

Rodney looked across at the grey-painted cruiser.

"Yes," he answered proudly, "I am to join to-day."

In the meantime a crowd was gathering around the aeroplane, eager to see it start on its renewed flight. A police-constable was approaching hurriedly down the slope of the cliff, no doubt with the intention of keeping off the curious crowd. As he came near to the camp, Rodney Redisham called out to him:

"Any news, Challis?"

"News, sir," responded Constable Challis, producing a journal from the front of his tunic, "I should just think so. Look here!" He opened the newspaper. "England has declared war," he announced.

Lieutenant Aldiss gave a quick glance at the prominently printed lines, handed his empty cup to Hilliger, and, swinging round, made a bee-line for his aeroplane, accompanied by Rodney Redisham, who helped him to start.

"Yes," continued Constable Challis, excitedly, "it's war—war against Germany—war to the knife. We're going to be put to the test. It'll be tough while it lasts. But you can take it from me, we shall win. We shall sweep the Germans off the face of the seas, and make an end of 'em!"

"Not a bit of it!" cried Max Hilliger exultantly. "It will be the other way about. Ha, ha! England's done for now! She's doomed. Every cockboat in her rotten fleet will be sent to the bottom. D'you hear? She's doomed! She'll be smashed—smashed like that!"

He dashed the empty cup in fury to the ground. There was a hearty burst of laughter, for the cup fell upon the soft sand and was not even cracked. Enraged at the failure of his illustration, and the laughter which seemed to mock him, Max snatched his Sea Scout's cap from his head and deliberately flung it full into the face of Mark Redisham.

Mark caught it with a quickly uplifted hand, and politely offered it back to him.

"Don't make a silly ass of yourself," he smiled, "even if you have become our enemy."

But instead of taking it, Hilliger turned away, strode sullenly to his bicycle, mounted it, and rode off in the direction of the town and the harbour.

CHAPTER II.

THE PERIL OF THE SILVER PIT.

"Ah, this is just what I like!" declared Mark Redisham from his elevated perch on the trawler's windward bulwark. "It's heaps better than being ashore in camp!"

Darby Catchpole, seated beside him, clapped his feet together in delight.

"It's lovely," he agreed; "I wouldn't have missed it for anything."

They were far out on the blue waters of the North Sea, steaming towards the fishing grounds of the Dogger Bank in the trawler What's Wanted, an entirely new craft, owned by Catchpole's father and now making her first working trip.

"It's a pity none of the other chaps are with us," regretted Redisham.

"You needn't be sorry Max Hilliger isn't here," Darby responded. "He turned ridiculously crusty yesterday morning when the constable spoke about our beating the Germans. I suppose it was natural, since he's a German himself. Of course, he couldn't have stopped in the troop, even if he'd wanted to, being one of the enemy. But he might have had the grace to pay his debts. Mr. Bilverstone will never get the three shillings he owed him."

"Why? Max hasn't left the town, has he?"

"Yes, he has. He went off by the afternoon tide in that Dutch ketch that has been lying in the Roads so long. I suppose we've seen the last of him."

Redisham glanced round the wide stretch of sea, as if in search of the ketch, but there was no sign of her.

Darby jumped down from his perch, and Mark followed him aft, past the wheel-house, to find the skipper giving instructions for the trawl to be put out. They were now near the fishing grounds of the Silver Pit, a favourite spot for longshore soles and turbot.

When the trawling gear was out, the skipper and his two guests went below for breakfast in the tiny compartment which did service as a cabin. In taking his seat at the narrow flap table, Mark Redisham had to make room for himself by removing a gun. He examined the weapon, and, recognising it, looked across at Darby Catchpole.

"Why on earth have you brought your fowling-piece with you?" he asked in surprise. "Do you expect that you may need to defend yourself against the enemy?"

Darby laughed.

"No," he explained. "I told you once that I'm helping to complete the collection of East Coast birds for the Haddisport Museum. They don't possess a specimen of the common or North Sea tern. I thought perhaps I might get one."

He took his fowling-piece on deck with him. There were many sea birds—gannets, mews, and fulmars—flying about, but the graceful sea swallow was absent, and he transferred his interest to the work of hauling in the trawl.

The first take was disappointing; the second more fortunate. Time after time the gear was brought in, and gradually a considerable number of fish accumulated.

Redisham had brought with him a pair of marine glasses, of which he was especially proud. They were particularly powerful, and he was constantly testing them by trying to read the names on distant ships. At about nine o'clock he was idly searching the horizon, when his attention was arrested by a strange sail to the far north-east.

"Darby!" he cried. "There's that Dutch ketch! Have a look at her."

Darby took up the skipper's telescope from the top of the skylight and adjusted the focus.

"Yes," he agreed, after a while. "It's the same, no doubt. I know her by her weatherboard. But what's she up to? She's bang in the track of the steamer bearing down on her! Hullo! The steamer's stopped! Wait a bit. The Dutchman's putting out a boat."

The two Scouts watched what was going on across the sea—the rowing boat pulling alongside the steamship and returning to the ketch, having apparently disposed of some of its passengers.

Why should this transfer of passengers be made in the open sea? And had Max Hilliger anything to do with it?

Mark made out the steamer to be a vessel of about 2,000 tons. She had two cream-coloured funnels, and was furnished with many lifeboats and deckhouses, like a liner. He tried to read her name, but it was hidden by the anchor chain. It satisfied him, however, that she was flying the Red Ensign, and he took no further notice of her as she continued on her course south by west.

Shortly afterwards he was startled by the report of Darby's fowling-piece.

"Got him!" cried Catchpole. "It's a tern."

Darby was a good shot, and he had brought down the bird, which had fluttered into the sea hardly a score of yards from the trawler's starboard side.

The skipper made no demur when asked to reverse the engines. The boat was lowered, and Darby secured his prize. But his disappointment was great when he discovered that the bird was not a tern, or a web-footed sea bird of any species, but an ordinary domestic pigeon. He was on the point of casting it back into the sea when Redisham checked him.

"Wait!" cried Mark. "Which way was it flying?"

Darby looked at him in perplexity.

"What's your idea?" he questioned. "It was flying from north-east to south-west."

"Just what I guessed," returned Mark, with a significant nod. "It was going towards Haddisport from the Dutch ketch. It's one of Max Hilliger's pigeons. Let's have a look at it."

They examined the dead bird, and sure enough they discovered a strip of thin paper bandaged round one of the legs. The writing upon it was in minute shorthand.

"It's German!" declared Mark. "We must give it up to some naval officer to translate. I'll keep it in my pocket-book, shall I—till we get home?"

"Perhaps it came off the steamer, and not the ketch," suggested Darby.

They turned to look for the steamship, and saw her steaming southward, across their own wake. Although she was many miles away, it was possible now to distinguish her name, for the sunlight was upon her. They spelled out the words Minna von Barnhelm.

"Why, she's a German!" cried Mark, "and now she's flying the German naval ensign! Hullo! That's queer! There's something gone wrong with her. She's sprung a leak, surely! She's jettisoning her cargo. Have a squint at her!"

A large, dark object, like a cask or packing case, fell with a light splash into the sea under the steamer's counter. It seemed to have dropped from an inclined plank put out under her taffrail. She was going slowly while this was being done, but presently she put on steam and moved off, gathering speed, and was soon a mere speck in the far south.

The What's Wanted now altered her course to the westward, steered by Mark Redisham, for the two Sea Scouts were allowed to take each a spell at the wheel.

During every moment they were learning something new. What Darby enjoyed as much as anything was to work the winch which hauled in the loaded trawl; but always when the gear was brought inboard there was the excitement of emptying the pocket of the net and seeing what varieties of fish and strange marine creatures had been dredged up.

Darby was at the winch one moment, while Mark was pricking off the trawler's course on the chart, when the mate at the stern shouted excitedly:

"Belay there! Stop the winch, sir! Hold hard. We've fetched up a bit of wreck!"

Mark Redisham ran aft and looked over the side. The trawl beam was against the quarter bulwark, and a curious big, oval object, which at first glance looked like the back of a huge fish, was jammed between the beam and the vessel's side.

Mark leant over, and looked at the thing more closely; then he leapt back, trembling from head to foot.

"Steady all!" he cried hoarsely. "Don't move that winch, Darby! For the life of you, keep it still! Leave it, and come here—quick!"

Darby, the skipper, the mate, the engineer, the whole crew went up to him, staring at the thing which had so filled him with alarm. He alone seemed to know what it was.

"Stand back!" he cried. "Don't touch it! Don't go near it! It's a mine—a contact mine! If it's moved only an inch there'll be an explosion. See those spikes on the top of it? They're the detonators. One of them's resting on the rail! If it breaks—it's glass—if it breaks, we're all done for!"

The skipper, pocketing his pipe, looked through screwed-up eyes into the boy's face.

"Any c'nection with this yer war, Mester Redisham?" he coolly inquired.

"It has every connection with it," Mark answered calmly.

He went cautiously nearer to examine the exact position of the mine. It was balanced on its own circumference, held against the side by the trawl board; but every slightest movement of the ship threatened to explode it.

"We can't cut it away," he decided. He turned to the mate. "Dick," he ordered, "launch the boat very carefully and let us all quit."

Fortunately the boat was at the farther end, hanging outward from the davits. Mark advised the skipper exactly what to do. He pointed out that by passing a warp round the trawl gear and hauling upon it from seaward the mine might be released and slip back into the sea. This was the only chance, and in case it should fail, every one was to get into the boat.

He was himself the last to leave the ship. They took the longest rope, and, rowing round, contrived at great risk to lash an end of it to the lower extremity of the trawl beam. Four men were at the oars. Paying out the rope over the stern as they rowed away, they hauled upon it until it became fairly taut.

"Steady!" commanded the skipper. "Back 'er a bit—belay—row starboard!"

He manoeuvred the boat until the pull of the rope was at the proper angle, then the tension was slowly tightened. The trawl beam swayed very slightly at first; but suddenly there was a heavy jerk, the mine moved, but it was not dislodged. Mark Redisham saw one of the detonators bending.

"Look out!" he shouted.

Instantly the air and sea together were torn by a terrific crash, which must have been heard a score of miles away. In that instant Mark saw the whole fabric of the trawler burst open. The boat heaved under him, and he was flung forward, stunned and unconscious.

CHAPTER III.

WATCHERS OF THE SEA.

The sound of that explosion carried its warning far over the fishing grounds of the Silver Pit. It reached tramps and colliers plying their ceaseless traffic along the coast. Nearer at hand it alarmed the crew of the trawler Mignonette, who saw the column of smoke and wreckage shot skyward as from the crater of a volcano, and who, regardless of their own danger from floating mines, hastened to the spot to pick up the dazed survivors huddled together in the open boat. It reached the officers and men on a patrol of destroyers speeding northward within sight of the English shores. On the cruiser Atreus it was distinctly heard, coming like a challenge across the waves.

"Oho!" exclaimed the astonished commander, arresting his pacing of the quarter-deck. "Gunfire, eh? Hostilities are opening even earlier than we expected!"

He stood by the binnacle, listening for a second "boom."

"Seemed to me almost more like the explosion of a contact mine than a gun, sir," ventured the signal lieutenant, halting beside him.

"A mine?" protested the commander. "No, no, impossible! We have laid no mines. It is not in our programme to lay mines; and certainly not on the high seas. The enemy cannot have laid any, either—not over here; not so promptly, hardly thirty hours after the declaration of war. It cannot have been a mine. And yet there was only one detonation. If it had been a naval gun, it would have been answered. However, we shall soon know. We must go and see. Send out the signal to change course eight points to starboard."

It chanced that Rodney Redisham was midshipman of the watch, and that it fell to him to help in transmitting this signal.

With the precision of a battalion of soldiers at drill, the flotilla of destroyers and their guide ship wheeled first into line abreast formation and then into line ahead. The Atreus, which before had been leading, now held the rear station, following in the wake of the destroyers; and it was in this order that they appeared an hour later when sighted by Mark Redisham and Darby Catchpole from the deck of the Mignonette.

Mark was unhurt, excepting for a few bruises about the shins. Darby had a scar across his fore-head, and the skipper's head was badly cut; the mate's right arm was fractured, and all others of the crew had tested Mark's skill in first-aid. But they had escaped with their lives, even though the What's Wanted had disappeared.

"The blamed Germans!" complained the skipper, nursing his bandaged head. "And it was her maiden trip! The mean cowards to come sneakin' over here a-sowin' of their mines on the open sea for harmless fishin' craft to run foul of! 'T'aren't accordin' to any fightin' rules as ever I've heard on. 'T'aren't fightin' at all, nor honest warfare, look at it how you will!"

As the destroyers drew nearer, Mark Redisham grew more and more apprehensive lest they should run into the unsuspected danger of the mine-field, and he wanted to warn them of their peril. He urged the engineer to put on more steam and get close up, so that they might see their signals.

Already he had hoisted a flag signifying "I want to speak to you," and Darby was busy fashioning a pair of semaphore flags.

When the flotilla was near enough, Darby went to the steam whistle and opened the valve, giving a long, shrill blast to attract attention; following it with short and long blasts in the Morse code to form the message:

"You are running into danger. Steamer flying German ensign has been laying mines. Trawler sunk. Survivors on board me."

At the same time, Mark, taking the two flags, climbed upon the wheel-house, and, standing firmly, began to wave them, signalling very rapidly.

For a long time there was no response; but unknown to him, the leading destroyer had flashed its wireless message back to the cruiser. Presently the whole line came to a stop, and Mark saw that the semaphore on the Atreus was at work, questioning him. He answered, telling the whole story of the German mine-layer, and the loss of the What's Wanted.

Even while he was speaking, the motor-pinnace of the cruiser was launched, and the message came to him:

"If you, the Sea Scout, who are signalling, are one of the survivors, come aboard us immediately. Let your shipmates be taken into Haddisport."

Mark was not altogether surprised when he saw that the midshipman in charge of the pinnace was his own brother Rodney. They shook hands as he stepped into the stern sheets, but preserved a discreet silence before the men.

Saluting the quarter-deck as they boarded the Atreus, Mark found himself face to face with a group of officers. He advanced towards the commander.

"If you will lend me a chart, sir," he began, "I will show you exactly the way the mine-layer went. She has been sowing mines all along her track."

A chart was at once opened on top of the skylight, and with a pencil Mark traced as nearly as he could the Minna von Barnhelm's course, from the time when he first saw her until she disappeared.

"It was just here where she began laying mines," he explained, indicating the spot, "about three miles to the east of where we are now. If you keep well to the westward, you will escape them, sir. But I can't say which way she steered after we lost sight of her."

"Of course not," nodded the commander. "You have done very well as it is. I'm tremendously obliged to you for the information."

He turned to his officers and gave orders for the squadron to proceed at full speed in pursuit, handing the navigation officer the marked chart.

"There's another thing," resumed Mark, fumbling in his pocket-book, and producing the strip of paper taken from Darby Catchpole's pigeon. He explained how he had come by it, adding: "It seems to be written in German shorthand. Perhaps you will take charge of it, sir."

"Excellent," smiled the commander. "You have your wits about you, my lad. You have acted with commendable good sense and promptitude. This matter of the mine-field is most important. What is your name?"

"Redisham, sir—Mark Redisham. I am the brother of Midshipman Redisham."

"Indeed! Oh, then, just see if you can find him, and tell him from me to look after you until I want you again. Tell him he may show you over the ship!"

For a couple of hours or so Mark was in his glory going about the cruiser, examining the engines, the guns, the torpedo-tubes, inquiring into the mechanism of the water-tight doors, visiting the seamen's quarters, the conning-tower, and even watching the stokers at their grim work.

As they returned to the deck, a petty officer touched Mark's elbow.

"Captain Damant wishes you to go up to him on the bridge," he said.

Mark found his way, and climbed up to the commander's side.

"Take my binoculars and have a look at the steamer yonder," the commander told him, "and see if you identify her."

"I can identify her without the binoculars, sir," returned Mark. "It's the Minna von Barnhelm."

"Good," nodded Captain Damant. "I wanted to be sure. You can go now. Go and make yourself as small as you can in that corner of the conning-tower, and watch our destroyers. Don't be alarmed at the noise."

The destroyers were now stretched far in advance of the cruiser, bearing down upon the German in line ahead. Hardly had Mark settled himself in his corner, when the foremost of them fired a shot across the bows of the mine-layer.

The Minna von Barnhelm at once answered from small guns mounted on her upper deck, her shells falling short. Each of the destroyers fired a shot in turn, and every shot got home.

Within a few moments the mine-layer showed the terrible effects of the British guns. Her after-funnel fell over; one of her ventilators followed; her bridge was torn to shreds, and her top works were wrecked.

For a while it seemed to Mark that she was going to be left with this punishment, for the destroyers were continuing on their course, passing her on their port-beam. But presently he saw the immense four-inch guns of the Atreus herself being trained upon her from the forward barbette. Mark held his breath and waited, watching the long steel tubes moving as easily as if they were mere muskets taking aim.

Suddenly from one of them there was a great gush of fire and smoke, a staggering, deafening roar, which shook the whole ship, and a monster lyddite shell struck the Minna von Barnhelm on her quarter, exploding there with terrific violence.

Mark saw the gaping hole which it tore in the steamer's hull, and he knew that no further shots would be needed. She was sinking by the stern, the men at the same time leaping into the sea.

The British ships, with one accord, converged towards her, and from each of them boats were being launched to pick up the survivors. The Atreus was the nearest, and just as her first boat pushed off the Minna von Barnhelm heeled over, shuddered, and sank in a riot of foam.

Mark and Rodney Redisham stood together at the gangway of the cruiser as the first boatload of survivors were brought on board.

As the last of them came up the ladder, it was seen that he was hardly more than a boy, wearing a fisherman's guernsey and heavy sea boots. He held up his head unashamed, almost insolently.

"Why, it's Max!" Rodney Redisham exclaimed.

Max Hilliger stared at the two brothers, a spasm of hatred on his face. He clenched his fist to strike at one of them, when a couple of seamen, with a loaded stretcher, marched in between.

The Germans were at once led below to have their wounds dressed, and to be provided with dry clothing.

"You had better slip down to the petty officers' mess now, Mark, and get some grub," Rodney advised. "I will see you later on. We're going into Haddisport, I believe, so you'll be put ashore. The destroyers are to be sent off on another job, up north."

It was two or three hours before they again met. Mark had had dinner, and was sitting chatting with a company of petty officers, when Rodney came to him.

"You're wanted in the chart-room," he announced. "Come along!" And as they were passing aft through one of the alley-ways, he added: "Captain Damant has had that pigeon message translated, and it seems to be important. He's going to ask you something about it."

Mark followed him up a flight of stairs to the deck.

At that moment there came a low, rumbling sound from under the bows of the Atreus. Then the frightful, ear-splitting crash of an exploding mine. A sheet of flame instantly enveloped the bridge. The vessel's back seemed to be broken. She listed over to the port side with such a jerk that all who were on deck were flung off their feet. Mark Redisham was pitched bodily over a machine-gun and flung far out into the sea.

He sank down, down into the depths. It seemed an age before he felt himself rising. At length, when he came to the surface, gasping, it was to find the air filled with falling splinters and a dense yellow smoke which almost choked him as he tried to breathe. He saw the doomed cruiser some distance away settling down by the bows.

He looked around him. Most of the debris from the explosion had been of metal and had sunk. But he caught sight of a floating spar. He swam towards it. It was not large enough to support him, but it would help to keep him afloat until the poisonous fumes should clear.

He reached it and stretched forth a hand to grasp it, when another swimmer, coming behind him, shoved him violently aside and seized it.

Mark went under for a moment, rose again with his throat full of sea water, and grabbed the nearer end of the spar. As he did so he saw the other's face. It was the face of Max Hilliger.

They stared at each other. Both knew that one must yield.

"It's my life or yours," said Mark. "Which is it to be?"

CHAPTER IV.

THE MENACE OF THE MINES.

Hardly had Mark Redisham spoken the challenging words, when he realised that even if Max Hilliger should choose to yield to him the coveted chance of safety, he could not accept it. How could he afterwards forgive himself if he saved his own life at the cost of another's—even though that other were an enemy of his country?

The instinct of self-preservation was strong within him. He knew that by a turn of the hand he could take possession of the spar which would keep him afloat; he knew, too, that Hilliger was the better swimmer. But he did not hesitate.

"Take it," he said, pushing the spar from him.

He waited to see Hilliger seize and rest his arms over the support. Then he turned over on his side and struck out, swimming more easily among the waves than he had expected to do in his clothes and heavy boots. He could breathe more freely now, for the stifling fumes from the exploded mine no longer caught at his throat.

Uncertain of his best direction, striving only to keep his head above water, he glanced from side to side. In a ragged cloud of brown smoke and escaping steam he could dimly see the stricken cruiser, now about half a mile away.

She was perilously low in the bows, her afterpart tilted up, the blades of her propellers showing. Yet she did not seem to be sinking deeper. He supposed that her water-tight bulkheads had been promptly closed, that she still might keep afloat for hours.

Turning to see if Max Hilliger were following him, he caught sight of the destroyers rushing to the rescue, in spite of the danger from mines. He had not known that they were so close in the wake of the Atreus. Rodney had told him that they were going off on another job. He wondered if they would be able to save the ship by towing her into shoal water.

The shrill blast of a bugle reached him from the cruiser. As the smoke lifted for a moment he saw a throng of men on her decks, throwing things overboard—booms, hammocks, baulks of timber, crates, wooden gratings—anything that might help in saving life. Her boats appeared to have been smashed by the explosion. Everything beyond the bridge was wrecked—a funnel had fallen, the fire-control platform was down. He could see a gap in the forward turret, from which the great guns had been dislodged.

He thought of the stokers and engineers. None of the crew who had been in the forepart of the vessel when she struck the mine could have had any chance of life. Even as he swam, he passed many gruesome signs of the terrible destruction. He turned abruptly at sight of an uplifted hand and a young seaman's blood-stained face, which appeared immediately in front of him. He stretched out and caught at the man's wrist.

"Can I help you, mate?" he panted.

"No use, sonny," the seaman answered feebly. "Never you mind me. I've lost a leg, and I reckon my starboard side's stove in."

Mark held on, trying to get his free arm round the man's body. But he was drawn under, struggling, losing his grip.

When again he rose exhausted to the surface, and began once more to swim for his life, he was himself seized by the shoulder and pushed from behind. He made a spurt to free himself, and his right hand came down upon something solid, at which he grabbed with desperate fingers. It was one of the gratings that had been thrown overboard.

"Hold on to it!"

He heard the words confusedly through the buzzing of the sea water in his ears. He did not recognise the voice as that of his brother. Before he could turn to speak, his rescuer was swimming off again to the help of other possible survivors.

Mark reached over and managed to get a shin against the edge of the grating, pulling himself up until he rested bodily across the support. Thus raised above the surface, clinging with hands and knees, he could look round in search of swimmers who might share his refuge.

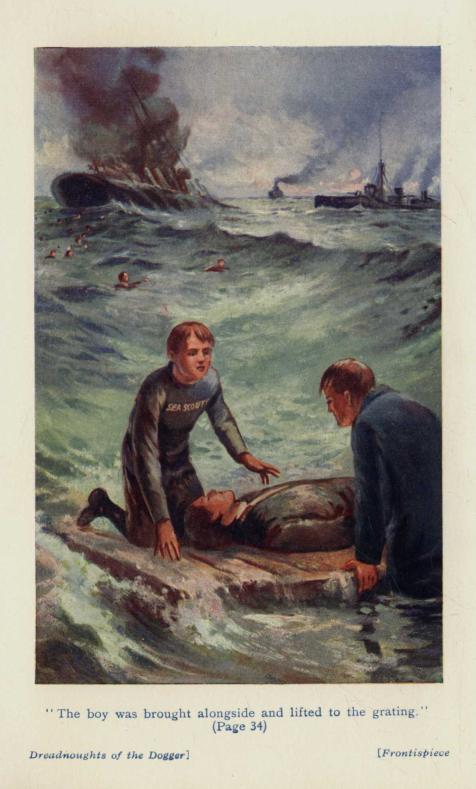

A little distance away he saw, and now recognised, his brother Rodney, swimming back to him with a hand under the chin of a wounded midshipman. The boy was brought alongside and lifted to the grating; but Mark Redisham saw that he was already beyond all need of human help.

Rodney clambered upon the raft, and saw what Mark had seen.

"He was one of my pals at Dartmouth," he said. "Look around and see if there are any others."

"Max Hilliger is somewhere about," Mark answered; "but I see no sign of him."

"I expect he will be picked up," returned Rodney. "See! There's one of the destroyers putting out her boats."

The leading destroyer had meanwhile come close up to the Atreus, and was sending out a hawser, with the intention of getting her in tow by the stern. It was soon obvious, however, that this attempt to save the vessel was useless. She was settling down, the waves washing over her bows, her stern tilted high.

It was clearly time to abandon the ship. The order to do so was given; the men were falling in on her steeply sloping quarter-deck. Boats from the destroyers were pulled alongside, and without hurry or confusion men, officers, and captain left her to her fate.

A boat from the destroyer Levity picked up Rodney and Mark Redisham. Still in their wet clothes, they gave help in attending to the wounded. All of the survivors who were not hurt had been in the afterpart of the ship when she struck the mine. Those who had been below in the stokeholds and seamen's quarters were killed to the number of a hundred and forty men, apart from some thirty of the German prisoners taken from the Minna von Barnhelm.

Nor was this the end of the disaster. The destroyer's boats had barely drawn off from the sinking cruiser when she struck a second mine. It exploded the fore magazine. Two of the rescue boats were smashed; wreckage, falling from a great height, struck others, and one of the cruiser's shells, bursting on the deck of the Levity, killed three men.

When this happened, Mark was giving first-aid to a wounded signal-boy who had been carried below into the temporary cockpit. The shell exploded with a deafening crash just above his head. It seemed as if the stout deck plates were burst asunder. He betrayed no alarm, but went on with his work of attending to the signal-boy, until the surgeon came with his instruments and bandages.

Mark returned on deck, wondering what had happened, and was in time to watch the shattered Atreus taking her final plunge—the third ship which he had seen sent to the bottom of the North Sea on that memorable day!

Captain Damant stood near him, also watching.

"I should not have regretted it so much if she had been sunk in fair fight," the captain was saying to one of the officers. "This wholesale mine-laying, however, is something unexampled, and contrary to all international law. It is clear, too, that the enemy must have begun the work days before the declaration of war."

Mark saluted him.

"You wished to see me, sir," he reminded him.

"Yes," the captain nodded; "I wanted to know if the Minna von Barnhelm was the only suspicious-looking craft you saw this morning. But it is now obvious that she was not alone. I don't suppose," he added, "that you quite realise how important it was that you should give such prompt information."

"We didn't save the Atreus, sir," Mark regretted.

"That is true," acknowledged Captain Damant, "because, as a matter of fact, we altered our course, and ran into another mine-field. The important thing is that our wireless message was picked up by a squadron of our Dreadnoughts off the Dogger Bank. They were steaming towards the danger. What do you suppose would have been the result if they, as well as we, had run foul of those German mines? It is thanks to you that the Navy has been saved an even greater disaster than the loss of the Atreus. You may be sure I will see that your good services are recognised."

CHAPTER V.

UNDER THE SYCAMORE.

Long before the smoke of the destroyer flotilla blurred the clean line of the horizon, it was known in Haddisport that H.M.S. Atreus had been sunk by a floating mine. Among the first of the townspeople to hear the news was Darby Catchpole.

Darby had come ashore from the Mignonette, and had hastened to the naval signal station at the end of the pier to report what he personally knew of the mine-layer. His Sea Scout's uniform gave him a passport, and he entered the pavilion, undeterred by the armed bluejacket on guard at the door.

He found himself in a large room, in which were several officers and seamen. The officers were discussing a wireless message received from Captain Damant. He heard one of them transmitting the message by telephone. Another was working at the telegraph instrument. From an inner room came the busy clicking of a typewriter.

An officer whom he knew by sight as Lieutenant Ingoldsby, commander of a submarine, came up to him, and Darby told him of the loss of the What's Wanted, adding that another steam trawler, the Pied Piper, had met a similar fate, with the loss of all hands.

"I suppose the fishing will be stopped, won't it, sir?" Darby ventured anxiously. His father was an owner of several trawlers, and he foresaw the possibility of ruin.

"Not necessarily," the officer assured him. "We shall soon clear the sea of mines. If you are not otherwise on duty, you can be useful here."

Darby's eyes brightened.

"I'm ready now, sir, this minute, to do anything I can," he said.

"Good!" Lieutenant Ingoldsby nodded approval of this prompt willingness. "Go into the farther room, there. They'll tell you what to do."

Darby entered the tiny, sunlit room, from which he had heard the clicking of the typewriter. Two bluejackets stood between him and the table. One of them moved aside.

"A Sea Scout just come in, sir," he announced to the man at the typewriter.

The operator wheeled round, and Darby was astonished to recognise his own Scoutmaster, Mr. Arnold Bilverstone. He was aware that Mr. Bilverstone was in the Royal Naval Reserve. What surprised him was that Mr. Bilverstone had so quickly been installed in naval duties, and that he should already be wearing the uniform of a petty officer.

Responding to Darby's salute, Mr. Bilverstone questioned him concerning himself and his adventure, and, gathering a sheaf of papers, said:

"Take these to the Harbour-master. They are lists of selected steam trawlers that are to be brought at once into the inner harbour to be turned into mine-sweepers, flying the White Ensign."

Not Darby Catchpole alone, but several other Sea Scouts of the Lion Patrol were occupied about the town and harbour that afternoon, helping to convert a fleet of fishing boats into a fleet of naval auxiliaries.

Instead of trawling for fish, these stout little vessels were to engage in the perilous pursuit of picking up explosive mines from the waters of the North Sea. It only needed that their funnels and hulls should be painted grey, and that some alterations should be made in their dredging gear, and they were ready for their new and dangerous work, each with her daring crew of naval reserve men.

In the late afternoon, Darby watched the first of them going out, under the escort of a gunboat. It was astonishing how wicked looking a coat of war paint had made them.

He lingered at the naval base until the survivors of the Atreus were landed in boats from the destroyers, and with other Sea Scouts he helped in conveying the wounded to the hospital. On his return he met Mark Redisham, who told him of how Max Hilliger had been on board the German mine-layer.

"I've been looking and asking for him," said Mark, as they walked together across the swing-bridge. "I supposed he'd been picked up by one of the destroyers; but nobody seems to know anything about him. I'm afraid he is drowned. We'd better call and tell his people."

Darby Catchpole shook his head.

"I've just heard that his people have left the neighbourhood," he explained. "Mr. Hilliger, being a German, couldn't very well stay in Haddisport. Of course, the consulate has ceased to exist. He has had to shut up his office and apply for his passports. I shouldn't be at all surprised if he, as well as Max, was aboard that Dutch ketch—the Thor—that we spotted off the Silver Pit. Perhaps he even went with Max on board the mine-layer. Anyhow, he's said to have sold his business and gone off."

"It looks as if he'd known long beforehand that there was going to be war," Mark observed.

"That is what the men in the trawl market are saying," resumed Darby. "They are saying, too, that for years past he has been acting as an agent of the German Navy against Great Britain, using his fishing boats to fetch and carry information. What about that pigeon message? Had it anything to do with him? Did you get at what was in it?"

"Yes." Mark Redisham gave a cautious glance at his companion. "But I've got to keep it a secret."

"Right," nodded Darby. "Then I won't refer to it again. Are you going to call at Sunnydene? I don't suppose you will find any one there, except perhaps a caretaker. The German servants were dismissed quite a week ago."

Sunnydene was the name of the Hilligers' luxurious mansion on the edge of the cliff, to the north of the town. It was a conspicuous, stone-built house, with gables and turrets overgrown with creepers, flanked by fir trees grotesquely bent by the harsh winds of winter. In the middle of the front lawn there was a tall flagstaff, rigged like a schooner's mast, from which, on occasion, the German ensign was displayed. The lower as well as the upper windows commanded a wide expanse of the North Sea, and it was from one of them, opening upon the terrace, that Herr Hilliger had watched the Thor setting out, with his son on board.

Time and again during this day he had stood looking out towards the far horizon, as if he expected something to happen. And now in the dusk of the evening he was once more gazing outward, with an expression of grave anxiety in his watery, blue eyes.

"The pigeon has not yet come home, Seligmann!" he said, turning sharply and speaking in German to his secretary, who had just entered the room carrying an overcoat and a yellow leather handbag.

"No, mein herr," the secretary answered, "I have again been into the loft. It has not returned. And already the car is at the door. It is time that we start."

"Strange!" ejaculated Heir Hilliger. "I cannot understand it. Max was to set it free at ten o'clock this morning. A bird that has so often found its way across from Heligoland is not likely to have lost itself on a shorter journey. It cannot be that the Minna von Barnhelm failed to come out from Cuxhaven. She was to have been at sea, equipped and ready to begin her work at once when Max should signal to her that war had been declared. Nothing can have gone wrong—nothing!"

He strode impatiently to and fro about the room.

"There is no help for it, Fritz," he resumed. "You must go without me. You have your passport. You will go by motor-car to Harwich, catch the night boat for the Hook of Holland, and join Max at Wilhelmshaven. You understand?"

"I understand, mein herr," returned Fritz Seligmann. "I have everything ready—the money, the secret code book, the plans, the letter to Admiral von Hilliger. But it is unfortunate that you come not also. If already our brave battleships are coming over for the great invasion, it will be better that you are in Germany rather than here in England."

"Very true," agreed Herr Hilliger. "But before three days I shall no longer be in England. I shall be on board the Admiral's flagship. Why should I remain in the enemy's country when I can be over there in my own, doing my duty for the Fatherland?"

An hour later, when the loaded car had gone off on its journey to Harwich and the house was in darkness, he was out in the grounds, prowling among the deep shadows of the trees. He seemed to have no object in his wanderings; but presently he entered the stables, empty now of both horses and motor-cars. He looked up into the blackness of the rafters, where the open square of a trap-door showed dimly. Then he determined to climb up into the pigeon loft. He clutched the sides of the ladder, his foot was on the lowest rung, when the sound of a footstep startled him. A hand caught agitatedly at his elbow. He turned with a nervous gasp, and drew back in amazement, as if he had seen a ghost.

"Max!" he cried. "You! Here? How is this? What has happened?"

Max stood facing his father, disguised in the engineer's cap and jumper that he had borrowed in place of his own wet garments on the destroyer which had brought him to land. He was breathing heavily, as if he had been running; as, indeed, he had, all the way from the harbour.

"I'm in time, then," he panted. "In time to stop you. But why are you not gone, hours ago? You got the message?"

"The message," his father repeated, recovering his composure. "It has not come. The bird is not yet home. You failed me. You did not set it free!"

"But I did, father!" protested Max. "It ought to have been here long since. I don't understand."

"Nor I," returned his father. "It was the best homing bird we ever had. Some one—why, what is the matter?"

Max was standing rigid, staring dazedly in front of him.

"I was thinking," he said slowly, "wondering—wondering if Mark Redisham——But no, it couldn't be. It's not possible. And yet there was that shot that I heard—a rifle shot—from across the sea! Are you sure the pigeon is not in the loft, father?"

"Never mind the pigeon now." Herr Hilliger drew him out into the stable yard. "Tell me what has happened. What of the Minna von Barnhelm? You signalled her? You went aboard? Why have you come ashore?"

"What?" cried Max in astonishment. "You have not heard? You have not been told? But she is sunk—sunk by the guns of a British cruiser—the Atreus. I was aboard of her—yes. I was picked up. And then the cruiser herself was blown up, sky-high, by one of our floating mines."

"Ah!" exclaimed Herr Hilliger, with a new eagerness. "Then the mines were laid?"

"Hundreds of them!" Max declared. "All along the coast."

"Good!" nodded his father, moving out from the yard into the drive. "We shall succeed."

He came to a halt under the shadow of a sycamore-tree.

"Listen, my son," he resumed, speaking very low. "This morning I have had a secret dispatch from Berlin. Everything goes well. Our brave soldiers are sweeping their way through Belgium. In a week they will march triumphantly into Paris. We shall have taken possession of Calais. The way to England will then be easy. Our battleships and submarines will command the Channel, and all the seas; cutting off supplies so effectually that Great Britain will be starved into submission, even before our transports and Zeppelins land their invading forces. Your opportunities, my dear Max, are even brighter than I had dared to dream."

He paused, drawing his son closer into the shielding shadows of the tree.

"But this delay in our getting over to Wilhelmshaven is most unfortunate," he continued. "As it happens, you had better have gone right across in the ketch, instead of changing into the Minna. As for myself——"

"Why didn't you go by the mail-boat from Harwich?" Max interrupted.

"My dear boy," exclaimed his father, "I waited for your message. All our plans—everything—depended upon my knowing the bearings of the Minna and my getting on board of her, as we planned."

"And now," pursued Max, "what do you propose to do?"

"Listen!" rejoined Herr Hilliger, still speaking in a cautiously low voice. "Everything that we now do must be in the service of the Emperor and the Fatherland. You and I are no longer concerned with England, in any way whatever, excepting in hastening her complete downfall. Great Britain must be beaten to the dust. And I have come to the determination that for the present we can best serve the Kaiser's cause by my going at once to Wilhelmshaven, leaving you here in England."

"Leaving me here?" cried Max in surprise. "But why? Why should I, a German, remain here among our enemies?"

"To be of the greatest use to his Majesty the Kaiser," returned Herr Hilliger. "You have been associated with the English people. You know them; you speak like one of them; you can pass yourself off anywhere as English. You can look about you without being suspected, seeing things which it is important that the Admiral and his captains should know."

"What?" Max ground his heel into the gravel. "You want me to stop here and find out the secrets of our enemies—to continue your underhand work of sending private information to Germany about the British fleet? You want me to betray the people who have been my friends? No, my father, I cannot do that. I am a German; I will fight for Germany. I will give up my life for the Fatherland. But I will not pretend to be what I am not. I will not be a spy."

Herr Hilliger laughed, a low, contemptuous laugh.

"My dear Max," he said, "since when did you learn that to be a true patriot it is necessary to consider the advantages of your country's enemies? It is nonsense. Your highest duty, as my son and as a German, is to do all you can against the arrogant English. You shall obey me. Do you understand? Tell me, once: how many people know that you are here in Haddisport? How many know that your life was saved when the British cruiser was blown to pieces by our faithful explosive mine?"

"Nobody knows," Max answered sullenly. "Nobody on board the destroyer which picked me up knew me, even by sight. I did not intend that any one should guess I was a German. Nobody who was on board the Atreus knows that I was not blown to bits—except—yes, except Mark Redisham. He saw me swimming. But he doesn't know that I was saved."

"Ah!" nodded Herr Hilliger. "And he need never know. He must never know—never. It is better that he should believe that you were drowned."

Max clutched at his father's arm, pressing him back upon the grass behind the tree.

"Some one comes!" he whispered agitatedly.

They both saw the lithe figure of a youth approaching silently up the drive. He paused for a moment, looking at the front door of the dark, deserted house, strode to the porchway, and quickly ran up the steps. In the silence the two watchers heard the tinkling of an electric bell; but neither moved. Strange that they should thus hide themselves in their own garden!

They waited, knowing that the door would not be opened. Herr Hilliger ventured to lean out and look towards the porch. As he did so, the revolving beam of light from the lighthouse, half a mile away, illumined the trees, travelled slowly over the towers and gables of the dwelling, glinted for an instant on the upper windows, then spread its glow across the sea. Against this glow he saw the figure on the doorstep, clearly defined.

"It is one of your Sea Scouts," he whispered.

The Sea Scout ran lightly down the steps, turned, and came quickly nearer, walking so quietly on the gravel that Max could only believe that he wore tennis shoes. Then, as he came yet closer, to within a couple of yards of the two Germans, again the beam from the lighthouse swung round and shone in his face.

It was the face of Mark Redisham.

CHAPTER VI.

WHAT MARK FOUND IN THE PIGEON-LOFT.

The two watchers under the sycamore-tree held themselves so very still and silent that even if he had been searching for them Mark Redisham might have passed by without a suspicion that they were so near. His well-trained senses were alert, but he was not consciously listening for any betraying sound or looking for any movement.

He went on along the gravel drive with confident stride until he reached the stables. Here he paused, glancing backward before entering the gateway of the yard. He had expected to find the gate shut and bolted, and was surprised to see that the door of the motor-garage also was open.

The place was in darkness, but he noticed that the motor-car was not there. This appeared to indicate that, although the family might have gone home to Germany, yet they had not dismissed all their servants. Mark reflected that probably the chauffeur, who acted also as gardener, had been left in charge of the house and grounds until the property should be sold or otherwise disposed of.

Mark had no intention of asking the caretaker's sanction to do what he had come to do. Indeed, it gratified him that his precautionary ringing of the hall hell had not been answered. He went boldly into the stables.

Knowing that he was about to use his electric torch, he closed the door behind him, lest the light should be seen. He knew the place well. Even in this past summer the Lion Patrol had had a scout game at Sunnydene. Pickets had been stationed at various points, and it had been his own part to steal into the grounds and make his way in the darkness into the harness-room without being caught.

He was now engaged in no ordinary scouting game, but in a serious duty imposed upon him by the officer in command at the naval base, and it was even more important that he should not be detected.

Feeling along the whitewashed wall, he touched the ladder leading to the loft. Up this he climbed through the trap-door.

He stood for some moments looking about him in the darkness of the loft. In the high door by which hay and straw were brought in there was a small hole, on a level with his eyes. Swallows used it as an entrance to their nests in the rafters. Going up to it and peering outward, he could distinguish the dark level of the sea, and presently the ruby gleam of the Alderwick lightship appeared, grew brighter, and faded against the dim horizon.

Mark realised that, if from here he could see that ruby gleam, it was certain that the crew of the lightship could equally well see the flash of his electric torch. Was it not possible that Heinrich Hilliger had used this hole in the loft door through which to flash his signals? Mark covered the hole by hanging his cap on a nail just above it.

Then he turned and closed the trap in the floor. It made more noise in falling than he had intended. Whether it was the displacement of air or his own fancy, there seemed to be a corresponding sound down below, as if another door had been suddenly shut, and as if the key of that other door had been turned in the lock.

"I suppose I'm a bit nervous," he said to himself. "It couldn't have been anything." He drew out his torch, pressed the switch, and turned the shaft of light upon the partition beyond which Hilliger's pigeons were kept. The key was in the door. Feeling like a guilty burglar, he turned it and entered, shielding the light from the open space in the gable by which the pigeons flew in and out.

There were no pigeons here now. The coops and perches were empty. He supposed that Herr Hilliger had taken the birds away with him, to use them in carrying secret messages back to England; although, as yet, there was no proof that Herr Hilliger had ever actually used any of his pigeons for this purpose.

Mark made a rapid survey of the untidy loft, with its lumber of old harness, rusty garden tools, bundles of sacking, broken fishing-rods, and discarded cricket bats. On a low shelf were some model yachts with torn sails and tangled rigging. He looked at the rough model of a steam trawler. The boat was curiously constructed with a boxed-in and bottomless well. Inside this well there was a crude model of a submarine. Some one—Max Hilliger, perhaps—had evidently attempted to invent a device by which a real submarine might be hidden within the casement of a larger vessel, thus enabling it to be brought close to an enemy without being discovered. The idea was ingenious, but obviously not practical.

In a corner cupboard he discovered a box of electric light bulbs of various colours. The sight of these led him to search for electric wires. He saw none; but what he did find was a portable electric lamp coiled round with a wire so exceedingly long that, as he estimated, the switch might be worked here in the loft while the bulb could be cunningly planted amongst the gorse bushes halfway down the cliff, there to flash its signals of coloured light.

Mark wondered if he should take the lamp away with him, but decided to leave it untouched. If as he believed, Herr Hilliger was already on his way back to Germany, and if Max were drowned, there could be no more risk of their communicating with the enemy.

He turned his torch upon the long trestle table at the far end of the loft. It was littered with feathers and grain, and thick with dust. But in the midst of the litter were several things which he considered it his duty to examine. The first article he touched was a match-box, half full of very small elastic bands. Beside it was a spool of thin, narrow paper.

"Here's proof enough!" he reflected with satisfaction. For he recognised the paper and the elastic bands as being precisely similar to the material found on the leg of the pigeon shot by Darby Catchpole from the deck of the What's Wanted.

For a little while longer he continued his search. From a pile of old newspapers and tattered books, he idly drew forth a long, tin cylinder, thinking at first it was a telescope case. The lid had been jammed on crookedly, and he had difficulty in pulling it off with the help of his knife. When he succeeded at last in opening the canister, he saw that it contained several tightly-rolled sheets of paper. He spread them out on the table. They were maps, plans, and charts, very carefully drawn.

The uppermost one was a general map of the coast, including Haddisport and Buremouth, with the villages between and a wide strip of the sea, divided into numbered sections. The others—and there were some twenty of them—were detailed enlargements of the same sections, upon which were shown the principal buildings of the two towns, the particulars of the harbours and railways, with every road and lane and bridge, every field and coppice and house, distinctly indicated.

Mark Redisham had never seen such wonderful maps, or imagined that any existed so complete and correct. Nothing seemed to have been overlooked. On the margins of each sheet were notes, written in German, with numbers referring to certain features in the plans.

Mark saw much that he did not then understand; but there was one sheet in particular which was perfectly clear to him. It was a large scale chart of the section of the North Sea immediately facing Haddisport, giving the exact soundings of the channels and shallows and showing an outline of the coast, with every altitude measured.

The soundings of Alderwick Knoll were so precise and plentiful that it was evident to him that some important purpose was connected with this sand-bank. He could hardly doubt, indeed, that the chart had been prepared for the guidance of an enemy attempting an invasion!

So greatly was he impressed by this idea, that he became nervously excited over his discovery. What was he to do? Should he carry these charts and maps away with him, now—to-night? He had not been instructed to take anything away with him; but only to "have a look round" and report upon any discovery he might happen to make.

Thinking over the situation for a few swift moments, he determined to obey his orders to the letter. Accordingly, he returned the sheets to the map-case, put the case back where he had found it, and prepared to leave the loft.

He left no trace of his secret visit. Taking his cap and pocketing his torch, he climbed down the ladder into the garage. He pushed lightly at the door; but it did not swing open. He pushed it harder; still it resisted. Then he put his shoulder to it and gave it a shove. It did not move. He grappled with it, trying with all his strength to force it open and, realised, to his alarm, that it had been locked from the outside!

He grew hot and cold by turns. Had he been watched, stealing into these stables where he had no business which he could truthfully explain? If so, who could it be that had watched and trapped him? It could not be Heinrich Hilliger himself, or Max. Herr Hilliger had gone back to Germany. Max was drowned. The chauffeur had not returned with the car. Once more he put his shoulder to the door. No. It was certainly locked! He was a prisoner!

But Mark Redisham was not a Sea Scout for nothing. There were more ways than one of getting out. He tried the door of the harness-room. That, too, was locked. Yet there was still another door, leading into the stable. It opened with a simple latch and he crossed to the door giving on to the yard. Again he was foiled.

He looked to the window. It was heavily barred.

But not even now did he despair. Beyond the vacant horse-boxes was a small opening in the wall—a hatch through which the stable refuse was forked out. This hatch, he knew, was fastened only on the inside by a hook and staple. In a moment he had flung it open, to climb out without further hindrances and make his way among the fruit trees and across the tennis lawn to the back gate of the Sunnydene property, and into the Alderwick road.

Five minutes after his escape, he was at home in his father's library, sending his report by telephone to the naval base.

His father, Major Redisham, had gone off to join his regiment, and the family supper was in consequence a melancholy meal. Mark said nothing of his visit to Sunnydene; but he was at liberty to tell his mother and sisters of the exciting events of the day—the loss of the What's Wanted, the sinking of the German mine-layer, and the terrible disaster to the Atreus.

"So you see," he concluded, "Rod was present at the firing of the first naval gun of the war!"

"Yes," said his mother; "but unfortunately Rodney's ship cannot be replaced, or the brave men who went down with her. He may not get another appointment for a long time. Is he coming home to-night, Mark?"

Mark shook his head.

"No, mother," he answered. "He was kept aboard the destroyer—the Levity. The whole flotilla went off to sea again as soon as the wounded were put ashore for hospital."

"I suppose they've gone to join the main fleet," his sister Vera conjectured. "Of course, the German battleships are out, and there'll be a great battle."

"The destroyers went south, however," Mark explained, "and the enemy fleet is much more likely to be hanging round off the Dogger Bank than down there in the narrow seas. It's my idea that the destroyers have gone into the Channel."

"Why?" questioned Vera. "What's the good of their going into the Channel when the Germans are in the North Sea? We want to fight them, don't we?"

"Well, you see," resumed Mark, "the British Army will be crossing to France. You don't suppose that ever so many of our transports—big liners crowded with troops—will be allowed to go over by themselves, at the risk of being sunk by German submarines? They've got to be protected on both flanks. I expect they'll steam across through quite an avenue of cruisers and destroyers."

Later, when Mark was saying good-night before going sleepily to bed, there was a ring at the front-door bell.

"Master Mark is wanted," the parlourmaid announced agitatedly. "There's a policeman and a lot of soldiers."

No longer sleepy, Mark hurried into the hall, where he found Constable Challis, Mr. Bilverstone, and two men in khaki.

"What's up?" he cried, seeing that the two soldiers were armed with rifles and fixed bayonets. "Are the Germans coming?"

"We want you to go with us," Arnold Bilverstone explained. "Get on your overcoat, and bring your electric torch. We're going to make a raid on Herr Hilliger's pigeon-loft."

Mark was quickly ready to march off at the head of the company. As they filed into the Sunnydene ground they saw that the house was in total darkness.

Leaving one of the sentries posted outside the stable yard, Mr. Bilverstone led the way round to the rear of the outhouses, where he posted the second sentry. Mark crossed the tennis-court, dodged under the fruit trees, and crawled through the hatch door which he had left unfastened. Mr. Bilverstone and Constable Challis followed him through the stable and into the garage. They mounted one by one into the loft. Mark flashed his torchlight along the floor, up into the rafters, and again along the floor. Then he stooped and picked up the stub of a cigarette, sniffed at it and shook his head.

"Somebody has been here!" he cried. "The end of this cigarette's still wet."

He went beyond the partition and began to search. But his search was in vain. The maps, the electric signalling-lamp and coloured bulbs, the model of the submarine, the spool of paper, the elastic bands—all had been cleared away. Nothing remained to show that the place was more than an abandoned pigeon-loft.

CHAPTER VII.

UNDER THE WHITE ENSIGN.

Because he was a Sea Scout, clever at semaphore signalling, with a knowledge of seamanship, resourceful, and generally handy, Mark Redisham had no difficulty in entering the Royal Naval Reserve, the more especially as he was strongly recommended by Captain Damant. It satisfied him greatly to be appointed at once as signal-boy and wireless operator on board His Majesty's steam trawler Dainty.

She was named the Dainty when launched, and as the Dainty she had toiled and battled for three stormy winters on the wild North Sea. But now her impudent white and red funnel and her gaudy hull were painted a sombre war grey, her trawling gear had been altered, her fish-well turned into a cabin, and the name on her bows had given place to the number 99. She was no longer a mere fishing craft, but classed as one of the great new fleet of naval mine-sweepers, flying the white ensign, and manned by a crew of sturdy East Coast fishermen wearing the blue jacket and loose trousers and flat-topped caps of the British Navy.

It was a proud moment for Mark when early on the morning following the "raid" on the pigeon-loft he went on duty, and the Dainty steamed out of Haddisport harbour and bore northward abreast of the lighthouse and past his home on the cliff. She was one of a squadron of twelve, and they went out in the company of the torpedo gunboat Rapid.

Word had come that the Germans had sown an extensive mine-field to the west and south of the Dogger Bank, scattering their deadly explosives over the seas, to the peril of peaceful trading vessels as well as of any British battleships and cruisers that might enter the area of danger. Two Danish cargo steamers and half a dozen English fishing boats had already been blown up, and our busy scavengers of the sea were now to go out and rake up the carefully-sown seedlings of death.

The work was dangerous, for at any moment one of the stout little vessels of the squadron might find a mine with her keel instead of with her stretched wire hawser, which meant ten more good men sent to the bottom. And there was always the risk of a premature explosion if a mine had to be handled in releasing it from its moorings.

Mines are not pleasant things to handle at any time—certainly not such powerful ones as the Germans employ, with glass "beards," or projecting spikes, the breaking of one of which results in an explosion great enough to sink a Dreadnought! They are charged, not with gun-cotton, but with the even stronger explosive known as T.N.T., which has the quality that if the mine filled with it strikes a ship it blows in the side of the vessel and then continues its destructive work in the interior.

The skipper of mine-sweeper 99 was Harry Snowling, R.N.R., an old salt who had fished for thirty years on the North Sea, and knew its deeps and shallows as well as he knew the lines on his own honest, weather-beaten face. But, of course, he had had no experience of mine-sweeping, and had only vague ideas as to how the mines were to be located.

"What's she doin' of, bor?" he questioned, when they were far out in the blue water, watching a seaplane sweeping overhead and flying to and fro athwart the gunboat's course.

"Well," said Mark Redisham, "I'm not certain; but I suppose she's looking for mines. They're not floating right on the surface, you know. They're held just about a foot below low water level, so that when a vessel passes she'll go bang on to them. But the pilot up there can see them, as a gannet sees a fish, and I expect he'll drop a signal when he spots one."

For something like an hour the seaplane searched, followed by the gunboat, with the trawlers moving in pairs in her wake.

When at length a signal was sent down that mines had been sighted, "dans," or small buoys with flags attached, were put out to mark the spot from which operations were to begin. Each couple of trawlers got ready their dredge tackle, dropping over the stern a long wire rope, heavily weighted. The weight drawn by each boat was connected with that of its partner by a yet longer wire hawser, weighted to keep it submerged and stretched below the level of the floating mines. The two vessels, ranging themselves on either side of the mine-field, steamed ahead on a parallel course, so that their submerged gear should catch upon the mooring-lines and sweep up the mines floating between them.

This process was carried on simultaneously by the other trawlers, clearing a wide lane through the mine-field, while the gunboat and the seaplane continued their searching for new fields.

When the mines were thus caught and brought to the surface, they were exploded from a safe distance by gunfire. You may be sure there were many narrow escapes from serious accident.

During the first afternoon, the Dainty and her working partner, the Ripple, brought up two mines together. They came into violent contact with each other, exploding so close astern of the Ripple that she was caught in the edge of the upheaval and badly damaged. Her crew made for the boat, thinking that all was over with them; but her skipper controlled them, and himself crawled below into the narrow space near the screw shaft, discovered the damage, and stopped the leak sufficiently to enable the pumps to keep the water down and save the ship.

Within a quarter of an hour of this accident, one of the other trawlers struck a mine and was shattered to fragments.

At the end of two days, the field having been cleared, the gunboat returned to port. Shortly after she had gone, Mark Redisham and his companions watched a squadron of British dreadnoughts and cruisers steaming safely across the area from which the danger had been so industriously removed.

Their trails of smoke had hardly faded from the horizon when Mark, still looking in the direction in which they had disappeared, noticed a curious disturbance in the calm water, about a couple of miles away.

At first he thought it was a school of gambolling porpoises showing their fins, but presently the periscopes and conning-tower of a submarine rose to the surface. The conning-tower was marked "U15," and he knew by this that she was German.

It seemed to him that she had probably been lurking in wait for the battleships that had just passed. If so, she had certainly missed her chance of doing them any damage. One of her officers climbed out to the conning-tower platform, looked searchingly around the sea, but quickly disappeared again, and the submarine dived, having paid no attention to the trawlers.

Mark, taking counsel with the skipper, went into the wireless operating-room and sent out a message, reporting what he had seen and giving the position. He did not expect his message to be picked up; but within an hour a British light cruiser came racing down from the north at twenty-five knot speed. The skipper and Mark watched her through their binoculars as she drew nearer, and identified her as H.M.S. Carlisle. They saw her suddenly alter her course, as though to avoid the mine-sweepers and possible floating mines.

"Her needn't be afeared," said Snowling. "Thar aren't no mines here now. Suppose you signals her, bor, and tells her it's all right!"

"Hold hard!" cried Mark. "Look! Look what she's after!"

In direct advance of the cruiser, he distinguished for a moment the two periscopes of the enemy submarine making a ripple as they moved through the calm water. In that same moment there was a gush of fire and smoke from one of the warship's 6-inch guns. A fountain of spray rose high into the sunlit air from where the shell had fallen. One of the periscopes seemed to have been struck. The submarine, evidently crippled, was emptying her ballast tanks to rise to the surface when a second shell struck her half-submerged conning-tower, smashing it like an egg.

"That's what I calls good marksmanship," declared old Harry Snowling. And going to the flag-halyard, he dipped his white ensign in salute.

The nearest of the trawlers hastened to the spot where the shattered submarine had gone down, hoping to save some lives; but nothing was found but a slimy patch of floating oil.

The Carlisle came within speaking distance of the trawlers, standing by for about an hour, and gave information of a new mine-field sown between the Dogger Bank and the Bight of Heligoland. Ten British trawlers, it was stated, had been captured by a German cruiser—the Schwalbe—which had taken them in to Emden. Their crews had been kept prisoners, and the boats had been fitted out as mine-layers to scatter mines indiscriminately wherever ships could sail.

The mine-sweepers were supposed to work in stretches of ten days at sea and six in port; but the Dainty and her companions continued at their task a longer time, for the danger was greater than ever the Royal Navy had counted upon.

Many neutral ships and fishing craft had been blown up, a British gunboat had been sunk, another badly damaged, and it was imperative that the seas should be kept clear. But at length a relief squadron from Grimsby came out to take over the work, and the Haddisport boats were dismissed for home.

Early on the next morning, Mark Redisham started up in his bunk, hearing the engines coming to a dead stop. He dressed himself in his oilskins and went out upon the rain-splashed deck. To his surprise he saw that a submarine had come close alongside. It was the H29, of which, as he remembered, his friend, Lieutenant Ingoldsby, was the commanding officer. One of her crew had been taken ill, and Lieutenant Ingoldsby wished the Dainty to take the man on board and nurse him until he could be put ashore in Haddisport.

The sick man had been carried over a gangway thrown across between the two vessels when Mark, happening to glance over the Dainty's farther bulwark, in search of the rest of the squadron which had gone on in advance, saw instead the dim shape of a three-funnelled cruiser looming ghostlike through the rain mist. She was flying no ensign, but by the look of her he was almost sure she was not British.

Not asking himself why he did so, he strode across the gangway to where Lieutenant Ingoldsby knelt, doing something with a spanner, on the narrow deck abaft the conning-tower.

"Good-morning, sir," he began. "I think the cruiser over there is signalling."

"Cruiser?" repeated Lieutenant Ingoldsby, springing to his feet. He climbed a few rungs up the ladder of the conning-tower, and looked out over the wheel-house of the Dainty, behind which the submarine was well hidden.

"Just slip below and ask Jardine for my glasses, Redisham," he ordered. "I believe it's the Schwalbe—the ship we've been stalking! In fact, I'm sure!"

Mark had never before been on board a submarine, and when he got to the foot of the perpendicular ladder of the hatchway, he became confused by the strange complexity of tanks and machinery. An electric light shone in the far end of a narrow passage. He was making his difficult way towards it when the great boom of a naval gun startled him. The Schwalbe was opening fire on the mine-sweepers.

He stood still. The silence following the gun shot was broken by the banging of an iron door above his head, and the sharply-spoken command rang out in Lieutenant Ingoldsby's voice:

"Prepare to dive!"

CHAPTER VIII.