A BAPTIST ABROAD

OR

TRAVELS AND ADVENTURES

IN

EUROPE AND ALL BIBLE LANDS

BY

REV. WALTER ANDREW WHITTLE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

HON. J. L. M. CURRY, LL.D.

WITH MAPS AND NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS.

“Where rose the mountains, there to him were friends;

Where rolled the ocean, thereon was his home;

Where a blue sky, and glowing clime, extends,

He had the passion and the power to roam;

The desert, forest, cavern, breaker’s foam,

Were unto him companionship; they spake

A mutual language, clearer than the tome

Of his land’s tongue, which he would oft forsake

For Nature’s page glassed by sunbeams on the lake.”

Childe Harold

NEW YORK:

J. A. HILL & CO.,

UNION SQUARE,

1890.

COPYRIGHT, 1890.

By J. A. HILL & COMPANY.

All rights reserved.

MOTHER

WILL READ THIS BOOK

THROUGH

TWO PAIRS OF SPECTACLES.

ONE PAIR

WILL MAGNIFY ITS VIRTUES

WHILE THE OTHER

WILL DIMINISH ITS DEFECTS.

THEREFORE IT

IS AFFECTIONATELY AND LOVINGLY

DEDICATED TO

MOTHER.

INTRODUCTION.

Next to seeing a foreign land with one’s own eyes is seeing it through the eyes of an intelligent, appreciative countryman. The word is purposely chosen, because one wishes to know what is observed and thought by a person who has tastes, sympathies and views in common with himself. A thousand things in a strange country are interesting and in different degrees. One studies historically, another socially, another politically, another ecclesiastically, while unfortunately not a few rush pell-mell bringing back the most superficial and indistinct impressions. Some find most satisfaction in architecture, while others have their chiefest enjoyment in sculpture, in painting, in natural scenery, in costumes and customs. No two have precisely the same fancies, and yet an observant, cultivated countryman is more likely to please us by what he likes and describes than is a foreigner whose point of view and whose mental habitudes are so different from our own. What is most pleasing in a book of travels is wide and varied observation, is an account of several[iv] countries inhabited by different races and distinguished by marked peculiarities.

This volume embraces a wide extent of travel, and includes an account of visits to Great Britain, Switzerland, Italy, Turkey, Greece, Palestine, Egypt, etc. The full table of contents is a little misleading, for the chapters pertaining to Europe are short, and Palestine takes up a considerable portion of the work. The author, avoiding what is dry or didactic, manages to compress into his pages much valuable and trustworthy information. His own religious denomination, naturally and properly, is not overlooked, and from eminent men he has succeeded in obtaining monographs which give interesting facts, drawn from most authentic sources. The portraitures of men, of whom everybody wishes to know more, constitute an interesting feature of the book.

The journey was not a mere vacation tour, a hasty gallop to points visited by circular tourists, but it comprised many months of patient toil, nor were the countries seen from the windows of the car of an express train. Lubboch, in his essay on the Pleasures of Travel, says that some think that every one should travel on foot “like Thales, Plato and Pythagoras.” Mr. Whittle is a pedestrian by choice, full of enterprise, activity, courage[v] and enthusiasm, and on foot he deviated often from the beaten paths, and had opportunities for careful examination of objects of interest and for much pleasant and instructive intercourse with the “common people.” With an eye quick to discern what was peculiar, with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge, he combined a cheerful disposition, a ready appreciation of the humorous, and has succeeded in giving the public a volume, every page of which is interesting.

Travel, as a means of improvement, of education, of broadening horizon, of getting us out of narrow ruts, can hardly be overestimated. A visit to Europe, Africa and Asia makes objective what was subjective, and gives realism to what was before vaguely in our memories. Some acquaintance with geography, with history, literature, art, enhances the interest and the profit. A young student who had visited Jerusalem was much flattered by a request from Humboldt to call and see him. The savant soon showed that from reading and inquiry he had more knowledge of the city than the youth had acquired by his visit. With some mortification and a little petulance the young man said: “I understood, sir, that you had never visited the Holy City.” “True,” replied Humboldt, “I never have; but I once got[vi] ready to go.” Mr. Whittle, with wise forethought, had made preparation for his visit. He knew what he wanted to see, traveled with a purpose, and has so imparted to his readers what he learned and observed that one catches in part the enthusiasm of the traveler.

J. L. M. Curry.

PREFACE.

“Around the World in Eighty Days” has had an extensive circulation, especially in America. The title is striking. Our people like to do things quickly. Many of them would be glad to girdle the globe in forty days. They forget that “what is worth doing at all is worth doing well.” Under the patronage of Tourist Agencies it has become quite fashionable of late to do Europe in three months. These flying trips do perhaps result in some good to the tourist, but they are valuable chiefly to the agencies under which they are made.

Traveling is no child’s play. Sight seeing when properly done is hard work, but hard work is the kind of work that pays best in the long run. To see any country aright and understand it correctly one must not merely visit its fashionable watering places, large cities, splendid abbeys and cathedrals, noted art galleries, museums, etc. He must see these things to be sure, but in addition to these he must, in order to get a correct conception, go out into the mountains, into the rural districts, and there study the soil, climate and products of the country. He must commune with the yeomanry the common people, and closely scrutinize their[viii] daily life and habits. He must see, as best he can, how climate, political surroundings, education, occupation, and religion affect their character. He must project himself as far as possible into the thoughts and feelings of the people among whom he is traveling. This prepares him to sympathize with them, and to look at things from their standpoint. The traveler is then prepared to reason from cause to effect. He has gotten hold of that golden thread of truth which leads to right conclusions. He is in condition to explain upon correct and philosophical principles the Socialism of France, the Skepticism of Germany, the Nihilism of Russia, and the Pauperism of Turkey.

Having under the providence of God been permitted to make an extensive and prolonged trip through the East, I determined from the outset to get out of the beaten tracks of travel. In applying the above-named principles, I walked a thousand miles through different European countries, and rode six hundred miles and more in the saddle through Bible lands. This necessarily gave me a varied experience, and brought me into close contact with every phase of nature and human nature. At times every faculty of mind and heart was stirred to its profoundest depths. I was forced to think. And, lest these thrilling thoughts should slip away from me, I determined “to fasten them in words and chain them in writing.” I agree with Gray that “a few[ix] words fixed upon or near the spot are worth a cartload of recollection.”

This accounts to some extent for the use of the present tense in the book, and also for the colloquial style in which it is written—it was composed on or near the spot. True, since then it has been carefully revised, re-written and enlarged; but originally it was written “on the spot.” I made these pages my trusted confidant. To them I expressed my “every thought and floating fancy,” and my words formed a true thermometer to my soul. But now I release these pages from all obligations of secrecy. They may tell it in Gath, and withhold it not in Askelon. I propose to take the public into my confidence. “In short, never did ten shillings purchase so much friendship since confidence went first to market, or honesty was set up to sale.”

I have carefully excluded all opiates from these pages. Brevity is the only claim I make to wit. I have not attempted to exhaust the subjects treated. My words are intended simply to strike the reader’s thoughts which may interpret further. “If you would be prudent, be brief,” says Southey, “for ‘tis with words as with sunbeams, the more they are condensed the deeper they burn.”

“Clarence P. Johnson” was my man “Friday,” and from some of the jokes gotten off at his expense the reader may conclude that he is a “man-eater,” as was that other Friday of Robinson Crusoe fame. But not so. This was his maiden[x] trip out of his native city. Such things happened to him while traveling as would naturally occur with any other youth under the same circumstances. He is a young man of fine spirit and extraordinary business capacity. He will some day be known and felt in the commercial world.

It gives me peculiar pleasure to acknowledge my indebtedness to Professor John R. Sampey, D. D., for valuable assistance rendered while preparing this book for the press.

I have made free use of a wide range of literature, but trust that in each case due credit has been given to the author. Many of the measurements given were made by myself, others have been taken from reliable sources.

While abroad, I made it a special point to study the history and outlook of the Baptists in each of the several countries through which I traveled, and I have not failed to record the result of my observations. But, in order to have Baptist history correctly, authentically, and impartially given, I have secured chapters from eminent men on the Baptists of their several countries.

W. A. W.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| OFF FOR NEW YORK. | |

| Preparations—A Prayer and a Benediction—An Impatient Horse and a Run for Eternity—Strange Sceptre and Despotic Sway—Beauty in White Robes—Approaching the Metropolis—Business Heart of the New World—A Bright Face and a Cordial Greeting—An Hour with the President—More for a Shilling and Less for a Pound—A Stranger Dies in the Author’s Arms—Namesake—Prospects of Becoming a Great Man—A Confused College Student—The Hour of Departure—Native Land. Page, | 23 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| ON THE HIGH SEAS. | |

| A Difficulty with the Officers of the Ship—A Parting Scene—Danger on the Atlantic—A Parallel Drawn—Liberty Enlightening the World—Life on the Ocean Wave—Friends for the Journey—The Ship a Little World—A Clown and his Partner—Birds of a Feather—Whales—Brain Food—Storm at Sea—A Frightened Preacher—Storm Rages—A Sea of Glory—Richard Himself Again—Land in Sight—Scene Described—Historic Castle—Voyage Ended—Two Irishmen. Page, | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE LAND OF BURNS. | |

| English Railway Coaches—Millionaires, Crowned Heads, and Fools—A Conductor Caught on a Cow-catcher—Last Rose of Summer—Off on Foot to the Land of Burns—Appearance of Country and Condition of People—Destination Reached—Doctor Whitsitt and Oliver Twist—The Ploughman Poet—His Cottage—His Relics—His Work and Worth—His Grave and Monument—A Broad View of Life. Page, | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| EDINBURGH. | |

| A Jolly Party of Americans—Dim-Eyed Pilgrim—Young Goslings—An American Goose Ranch—Birthplace of Robert Pollok and Mary Queen of Scots—The Boston of Europe—Home of Illustrious Men—A Monument to the Author—Monument to Sir Walter Scott—Edinburgh Castle—Murdered and Head Placed on the Wall—Cromwell’s Siege—Stones of Power—A Dazzling Diadem—A Golden Collar—Baptized in Blood—Meeting American Friends. Page, | 47 |

| CHAPTER V.[xii] | |

| A TRAMP-TRIP THROUGH THE HIGHLANDS. | |

| His Royal Highness and a Demand for Fresh Air—A Boy in his Father’s Clothes—Among the Common People—Nature’s Stronghold—Treason Found in Trust—Body Quartered and Exposed on Iron Spikes—Receiving a Royal Salute—Following no Road but a Winding River—Sleeveless Dresses and Dyed Hands—Obelisk to a Novelist and Poet—On the Scotch Lakes—Eyes to See but See Not—A Night of Rest and a Morning of Surprise—A Terrestrial Heaven—A Poetic Inspiration—A Deceptive Mountain—A Glittering Crown—Hard to Climb—An Adventure and a Narrow Escape—Johnson Gives Out—Put to Bed on the Mountain Side—On and Up—A Summit at Last—Niagara Petrified—Overtaken by the Night—Johnson Lost in the Mountains—A Fruitless Search—Bewildered—Exhausted—Sick. Page, | 57 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A GENERAL VIEW OF SCOTLAND. | |

| Highlands and Lowlands—Locked up for Fifteen Days—The Need of a Good Sole—A Soft Side of a Rock—The Charm of Reading on the Spot—A Fearful Experience—Bit and Bridle—Thunder-Riven—Volcanic Eruption—Dangerous Pits—An Hundred-Eyed Devil—Gloomy Dens—Meeting an Enemy—Eyes Like Balls of Fire—Voice Like Rolling Thunder—A Speedy Departure—Leaping from Rock to Rock—Silver Thread among the Mountains—Imperishable Tablets—The Cave of Rob Roy and the land of the MacGregors—Lady of the Lake and Ellen’s Isle—Lodging with Peasants and with Gentlemen—Rising in Mutiny—Strange Fuel—Character of Scotch People—Scotch Baptists—Sunrise at Two O’Clock in the Morning. Page, | 67 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| FROM DUNDEE TO MANCHESTER. | |

| Scotch Presbyterians in Convention—Their Character and Bearing—On the Footpath to Abbotsford—The Home of Scott—Five Miles through the Fields—Melrose Abbey and the Heart of Bruce—Hospitality of a Baptist Preacher—Adieu to Scotland—Merry England—Manchester—Exposition and Prince of Wales—Manchester and Cotton Manufacturers—A $25,000,000 Scheme—Dr. Alexander Maclaren—His Appearance—The Force of his Thought—The Witchery of his Eloquence—His Hospitality Enjoyed—A Promise Made. Page, | 75 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| BAPTIST CENTENNIAL. | |

| Three Baptist Associations—Centennial Year and Jubilee Year—Baptists Seen at their Best—Doctor Alexander Maclaren—Matchless Eloquence—Hon. John Bright Delivers an Address—Boundless Enthusiasm—English Hospitality—A Home with the Mayor. Page, | 84 |

| CHAPTER IX.[xiii] | |

| A SOJOURN IN ENGLAND AND ON TO WALES. | |

| Arrested and Imprisoned—Released without a Trial—Nottingham—Dwellers in Caves—Seven Hundred Years Old—Forests of Ivanhoe and Robin Hood—Birthplace of Henry Kirk White—Home of the Pilgrim Fathers—Home of Thomas Cranmer—A Guide’s Information—Home of Lord Byron—Wild Beasts from the Dark Continent—A Sad Epitaph—Byron’s Grave—A Wedding Scene—Marriage Customs—Wales and Sea-Bathing—Among the Mountains—Welsh Baptists—A Tottering Establishment. Page, | 90 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| LONDON. | |

| Entering London—The Great City Crowded—Six Million Five Hundred Thousand People Together—Lost in London—A Human Niagara—A Policeman and a Lockup—The Jubilee and the Golden Wedding—“God Save the Queen.” and God Save the People—Amid England’s Shouts and Ireland’s Groans Heard. Page, | 98 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| SIGHTS OF LONDON. | |

| Traveling in London—London a Studio—The Hum of Folly and the Sleep of Traffic—Five Million Heads in Nightcaps—Too Many People Together—Survival of the Fittest—Place and Pride—Poverty and Penury—Beneficence in London—East End—Assembly Hall—A Converted Brewer—His Great Work—Meeting an Old Schoolmate. Page, | 107 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| A TRIO OF ILLUSTRIOUS MEN. | |

| Joseph Parker—Canon Farrar—Charles H. Spurgeon. Page, | 118 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| NOTTINGHAM, CAMBRIDGE, AND BEDFORD. | |

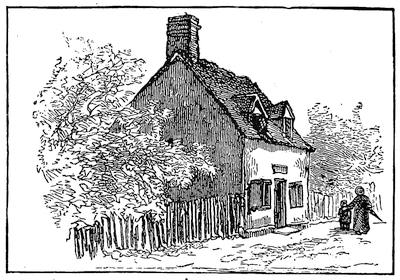

| Preaching to 2,500 People—Entertained after the Manner of Royalty—Excursion to Cambridge—What Happened on the Way—Received an Entertainment by the Mayor—Cambridge University—King’s Chapel—Fitzwilliam Museum—Trinity College—Cambridge Bibles—Adieu to Friends—Bedford—The Church where John Bunyan Preached—Bedford Jail, where Bunyan wrote Pilgrim’s Progress—Bunyan’s Statue—Elstow, Bunyan’s Birthplace—His Cottage—His Chapel—An Old Elm Tree. Page, | 123 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE BAPTISTS OF ENGLAND. | |

| Their Number and Divisions—The Regular Baptists—Their Movements and Progress. Page, | 130 |

| CHAPTER XV.[xiv] | |

| LAST OF ENGLAND AND FIRST OF THE CONTINENT. | |

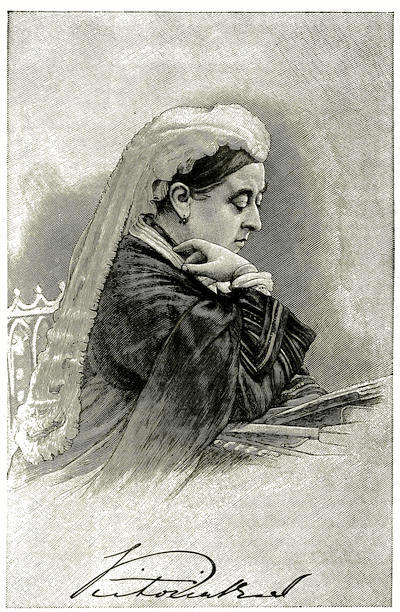

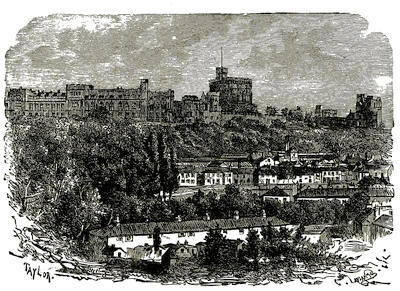

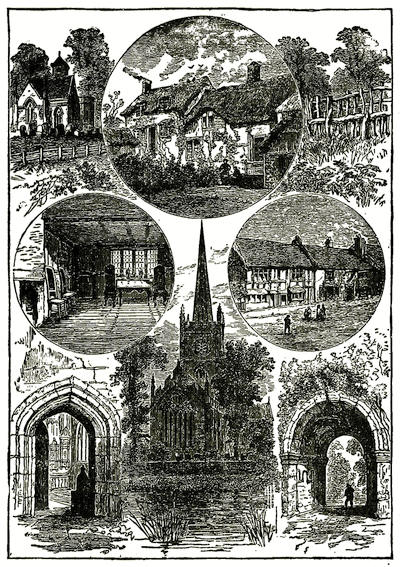

| Windsor Castle, the Home of England’s Queen—Queen Victoria—The Home of Shakespeare—Across the Channel—First Impressions—Old Time Ways—Brussels on a Parade—Waterloo Re-enacted—A Visit to the Field of Waterloo—A Lion with Eyes Fixed on France—Interview with a Man who Saw Napoleon—Wertz Museum—“Napoleon in Hell”—“Hell in Revolt against Heaven”—“Triumph of Christ”—Age Offering the Things of the Present to the Man of the Future. Page, | 143 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| FROM BELGIUM TO COLOGNE AND UP THE RHINE. | |

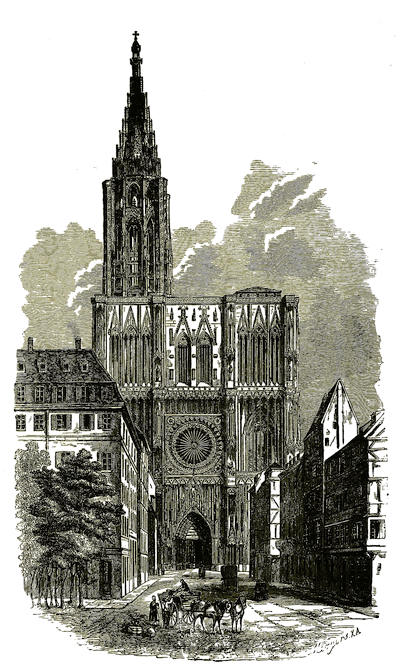

| Brussels—Its Laces and Carpets—Belgium a Small Country—Cultivated like a Garden—Into Germany—Aix-La-Chapelle—Birthplace of Charlemagne—Capital of Holy Roman Empire—Cathedral Built by Charlemagne—A Strange Legend—Shrine of the Four Relics—A Pulpit Adorned with Ivory and Studded with Diamonds—Cologne—Its Inhabitants—Its Perfumery—Its Cathedral—A Ponderous Bell—A Church Built of Human Bones—Sailing up the Rhine—A River of Song—Bonn—Its University—Birthplace of Beethoven—Feudal Lords—The Bloody Rhine—Dragon’s Rock—A Combat with a Serpent—A Convent with a Love Story—Empress of the Night—Intoxicated—Coblentz—A Tramp-Trip through Germany—Sixteen Thousand Soldiers Engaged in Battle—Enchanted Region—Loreli—Son-in-Law of Augustus Caesar—Birthplace of Gutenberg, the Inventor of Printing. Page, | 155 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| FROM FRANKFORT TO WORMS. | |

| Frankfort-on-the-Main—Met at Depot by a Committee—Frankfort, the Home of Culture and Art—Birthplace of Goethe—“He Preaches like a God”—The Home of Rothschild—A Visit to his House—Worms and its History—Luther and a Bad Diet—Luther Monument—Theses Nailed on the Door—Fame of Luther and his Followers more Imperishable than their Bronze Statues. Page, | 168 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| GERMAN BAPTISTS. | |

| A Weak Beginning—Persecutions—Firm Faith—Rapid Growth—A Trio of Leaders—Theological Schools—Publishing House—Hopeful Outlook. Page, | 174 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| OUT OF GERMANY INTO SWITZERLAND. | |

| A Lesson from Nature—Tramp-Trip through the Black Forests—Heidelberg Castle—Basle, Switzerland—Met by a Friend—Emigrants off for America—Delivering an Address to the Emigrants—The Grave of Erasmus—Gateway to the Heart of the Alps—Snowy Peaks—Rendezvous of the Nations—Beautiful Scene—Moonlight on the Lake—Sweet Music—Pretty Girls—Mountains Shaken with Thunder and Wrapped with Fire. Page, | 184 |

| CHAPTER XX.[xv] | |

| SWITZERLAND AS SEEN ON FOOT. | |

| Alpine Fever—Flags of Truce—Schiller and the Swiss Hero—Tell’s Statue and Chapel—Ascent of the Rigi—Beautiful Scenery—Famous Falls—Rambles in the Mountains—Glaciers—The Matterhorn—Yung Frau—Ascent of Mount Blanc—An Eagle in the Clouds—Switzerland and her People—The Oldest Republic in the World—“Home, Sweet Home”—High Living—Land Owners—Alpine Folk—Night Spent in a Swiss Chalet—Johnson in Trouble—Walk of Six Hundred Miles—Famous Alpine Pass—A Night above the Clouds—Saint Bernard Hospice—Overtaken in a Snow-Storm—Hunting Dead Men—The Alps as a Monument—Geneva—Prison of Chilon—How Time was Spent—Tongue of Praise. Page, | 190 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| BAPTIST MISSION WORK IN FRANCE. | |

| Incipiency of the Work—Obstacles to Overcome—Progress—Hopeful Outlook. Page, | 213 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| FROM VIENNA DOWN THE DANUBE TO CONSTANTINOPLE. | |

| A Black Night on the Black Sea—A Doleful Dirge—Two Thousand Miles—Vienna—Its Architecture—Its Palace—Its Art Galleries and Museums—Through Hungary, Servia, Slavonia, and Bulgaria—Cities and Scenery along the Danube—Products of the Countries—Entering the Bosphorus amid a War of the Elements—Between Two Continents—Constantinople—Difficulty with a Turkish Official—A Babel of Tongues—The Sultan at Prayer—Twenty Thousand Soldiers on Guard—Multiplicity of Wives—Man-Slayer. Page, | 220 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| FROM CONSTANTINOPLE TO ATHENS. | |

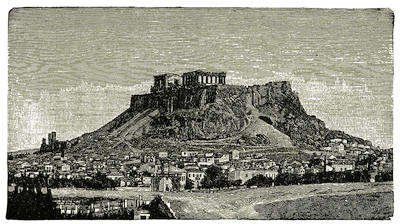

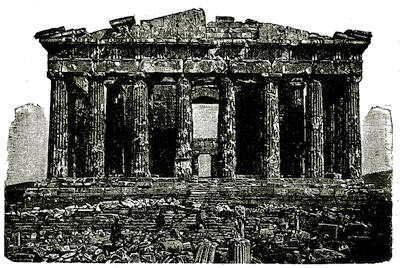

| A Stormy Day on Marmora—Sunrise on Mount Olympus—Brusa, the Ancient Capital of Turkey—Ancient Troy—Homeric Heroes—Agamemnon’s Fleet—The Wooden Horse—Paul’s Vision at Troas—Athens—A Lesson in Greek—The Acropolis—The Parthenon—Modern Athens—Temple of Jupiter—The Prison of Socrates—The Platform of Demosthenes—Mars Hill and Paul’s Sermon—Influence of the Ancients. Page, | 230 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| ASIA MINOR AND THE ISLAND OF PATMOS. | |

| Smyrna—Its Commerce—Its Population—Famed Women—Home of the Apostle John—One of the Seven Asiatic Churches—Martyrdom and Tomb of Polycarp—Emblematic Olive Tree—Out into the Interior of Asia Minor—Struck by Lightning—Visit to Ephesus—Birthplace of Mythology—Temple of Diana—Relics of the Past—Homer’s Birthplace—A Baptist Preacher and a Protracted Meeting—John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary—Timothy’s Grave—Cave of the Seven Sleepers—Return to Smyrna—Sail to Patmos—Patmos, the Exiled Home of the Apostle John—The Island of Rhodes and the Colossus—Death and Disease on the Ship—Quarantined—A Watery Grave—Hope Anchored within the Vail. Page, | 240 |

| CHAPTER XXV.[xvi] | |

| FROM BEYROUT TO THE CEDARS OF LEBANON. | |

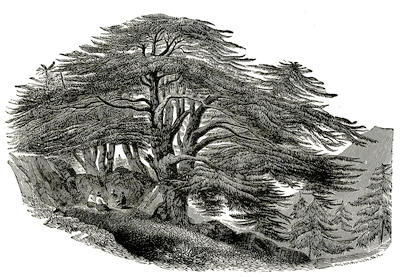

| Landing at Beyrout—Escape from Death—Thankful Hearts—Seed Planted—Desire Springs up—Bud of Hope—Golden Fruit—“By God’s Help”—Preparations—New Traveling Companions—Employing a Dragoman—A Many-Sided Man Required to Make a Successful Traveler—“Equestrian Pilgrims”—A Great Caravan—Ships of the Desert—Preparations for War—A Dangerous Mishap—National Hymn—Journey Begun—Mulberry Trees—Fig-Leaf Dresses—An Inspiring Conversation—The Language of Balaam—City of Tents—General Rejoicing—Tidings of Sadness—Welcome News—First Night in Tents—Sabbath Day’s Rest—Johnson and his Grandmother—A Wedding Procession—Johnson Delighted—Brides Bought and Sold—Increase in Price—Inferiority of Woman—Multiplicity of Wives—Folding of Tents—Camel Pasture—Leave Damascus Road—Noah’s Tomb, Eighty-Five Feet Long—Perilous Ascent—Brave Woman—“If I Die, Carry Me on to the Top”—The Cedars at Last—Emotions Stirred—“The Righteous Grow like the Cedars of Lebanon”—Amnon. Page, | 250 |

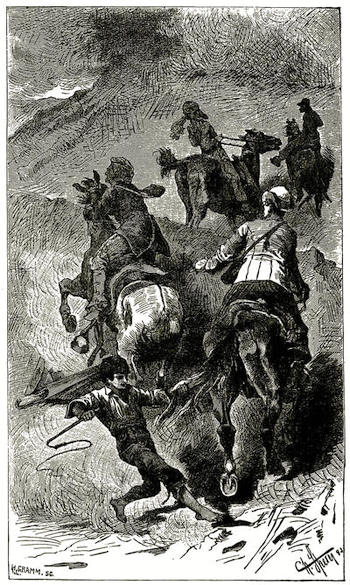

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| FROM THE CEDARS OF LEBANON TO BAALBEK. | |

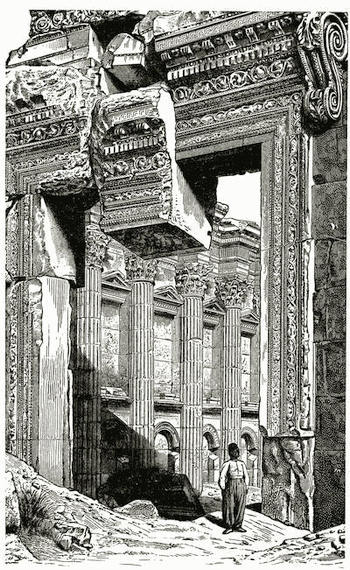

| Returning to Tents—Mountain Spurs and Passes—A Modern Thermopylae—Two Caravans Meet—A Fight to the Death—How Johnson Looks—Victory at Last—Into the Valley where the King Lost his Eyes—Playing at Agriculture—Squalid Poverty—Baalbek—Its Mighty Temples—Men, Mice and Monkeys—A Poem Writ in Marble. Page, | 269 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| DAMASCUS. | |

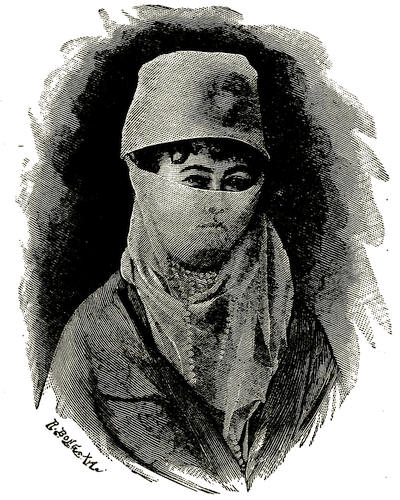

| A Beautiful Valley—Flowing Rivers—Mohammed at Damascus—Garden of God—Paul at Damascus—Mohammedan at Prayer—Valley More Beautiful—Damascus Exclusively Oriental—Quaint Architecture—“Often in Wooden Houses Golden Rooms we Find”—Narrow Streets—Industrious People—Shoe Bazaars—Manufacturing Silk by hand—Fanatical Merchants—“Christian Dogs”—Cabinet-Making—Furniture Inlaid with Pearl—Camel Markets—A Progenitor of the Mule—Machinery Unknown—Ignorance Stalks Abroad—Fanatical Arabs—A Massacre—The Governor Gives the Signal—Christians Killed—French Army—Abraham Our Guide—Brained before Reaching the Post-Office—Warned not to Look at the Women—Johnson’s Regret—Vailed Women—Johnson’s Explanation. Page, | 276 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| THE NAAMAN HOSPITAL FOR THE LEPROSY. | |

| Naaman, the Leper—His Visit to Elisha—The Prophet’s Command—Naaman Cured—House Turned into a Leper Hospital—Off to the Lepers’ Den—Origin, History and Nature of Leprosy—Arrival at the Gloomy Prison—Abraham, “I Didn’t Promise to Go into the Tomb with You”—“Screw your Courage to the Sticking Point”—Johnson’s Reply—Suspicious of the Arab [xvii]Gate-Keepers—A Charge to Abraham—Life in Johnson’s Hands—Mamie and the Currant-Bush—Among the Lepers—Judgment Come—Graves Open—Living Corpses—Walking Skeletons—Strewing out Coins—An Indescribable Scene—An Indelible Picture—Horrible Dreams. Page, | 292 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| FROM DAMASCUS TO THE SEA OF GALILEE. | |

| Sick, nigh unto Death—“Night Bringeth out the Stars”—Mount Hermon and the Transfiguration—Beautiful Camp-Ground—Amnon, the Reliable—“Thou Art Peter”—Fountain of the Jordan—Slaughter of the Buffaloes—Crossing into Galilee—Dan—Abraham’s Visit—A Fertile Valley—Wooden Plows—A Bedouin Village—Costumes of Eden—A Gory Field—Sea of Galilee—Sacred Memories—The Evening Hour—A Soliloquy—Bathing—Sailing—Fishing. Page, | 303 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| FROM THE SEA OF GALILEE TO NAZARETH. | |

| A Seven Hour’s Journey—A Rough Road and a Hot Sun—Gazelles—Nimrods of To-day—Historic Corn-Field—Cana of Galilee—First Miracle—Cana at Present—Greek and Roman Convents—Conflicting Stories of Greek and Latin Priests—Explanation—An Important Fact—Marriage Divinely Instituted—Woman Degraded—Woman Honored—Description of Nazareth—Childhood Home of Jesus—Jesus and the Flower-Garden—Studying Nature—He Goes to the Mountain Top—Without Bounds or Limits—A Fit Play-Ground and Suitable School-Room for the Royal Child—Rock Bluff where the People Tried to “Cast him down Headlong”—The Carpenter Shop—The Virgin’s Fountain—Nazareth at Present—Protestant Missions—A Short Sermon and a Sweet Song. Page, | 319 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| A CHARACTERISTIC SCENE IN THE ORIENT. | |

| Shepherd Tents—Many Flocks in One Sheep-Cote for the Night—Many Merchants from Different Countries—Ships Anchored—Arabs at Meal—Arabs Smoking—Shepherds with their Reed-Pipes—Merchants’ Response—Music and Dancing at Night—Bustle and Confusion in the Morning—Fight Like Madmen—Over-Burdened Camels—Camp Broken up—Dothan and Joseph’s Pit—Money-Loving Mohammedans—Crafty Jews—Return to Tents—The Shepherds Awaken—Crook, Sling and Reed-Pipe—David and Goliath—Shepherds under the Star-Lit Sky—”Glory to God in the Highest.” Page, | 337 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| FROM JERUSALEM TO JERICHO. | |

| A Man “Fell among Thieves”—The Way still Lined with Thieves—Guards Necessary—Across the Mount of Olives—Bethany and its Memories—David’s Flight from Jerusalem—”Halt! Halt!”—Seized with Terror—Splendid Horsemanship—”A Hard Road to Trabble”—Inn where the Good Samaritan Left the Jew—Brigands on the Way-side—Robbers and Guards in Collusion—Topography [xviii]of the Country—Dangers and Difficulties—Perilous Places Passed—Plain of Jericho—Writhing in Agony—The City of Palms—Trumps of Joshua—Jericho in the Time of Herod—Iron-Fingered Fate—Jericho at Present—A Divine Region—Pool of Moses—Antony and Cleopatra. Page, | 346 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| BEYOND THE JORDAN. | |

| Plain of Moab—Children of Israel—Moses’s Request—Moab a Rich Country—Lawless Clans—A Traveler Brutally Murdered—A Typical Son of Ishmael—Dens and Strongholds—Captured by a Clan of Arabs—Shut up in Mountain Caves—Heavy Ransom Exacted—The Moabite Stone—Confirmation of Scripture—Machaerus—John the Baptist—Prison Chambers—Character of John—How to Gauge a Life—Hot-Springs—Herod’s Visit—”Smell of Blood still”—Mount Nebo—Fine View—Life of Moses—From Egypt to Nebo—An Arab Legend—Death of Moses. Page, | 362 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| THE JORDAN. | |

| Two Thoughts—From Nebo to the River—Thrilling Emotions—Historic Ground—A Sacred Scene—An Earnest Preacher—Christ Baptized—Awe-Stricken People—A Sacred River—Bathing of Pilgrims—Robes Become Shrouds—The Ghor of the Jordan—The Valley an Inclined Plane—The Three Sources of the River—The Jordan Proper—Banks—Tributaries—Bridges—River Channel—Velocity of the Water—Its Temperature—Its Width and Depth—Vegetation along the Stream—Wild Beasts—Birds. Page, | 380 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| THE DEAD SEA. | |

| A Wonderful Body of Water—Receives 20,000,000 Cubic Feet of Water per Day—Has no Outlet—Never Fills Up—In the Sea—Johnson’s Suggestion as to my Identity—Why One Cannot Sink—”Salt Sea”—Caught in a Storm—Danger of Death—Dreary Waste—Sea of Fire—Johnson’s Argument—New-Born Babe—Child Dies—Lot’s Wife—Her Past History and Present Condition—The Frenchman’s Book—Why the Sea is so Salt—Why it Never Fills Up—Sown with Diamonds—Origin of the Dead Sea—God’s Wrath—The Sodom Apple—The Sea an Emblem of Death. Page, | 397 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| TWO RUSSIAN PILGRIMS, OR A PICTURE OF LIFE. | |

| A Steep Mountain—Rough Base—Beautiful Summit—Russian Pilgrims—Journey up Mountain—Life’s Hill—Courage in Heart—Marriage Altar—Long Pilgrimage—Star of Hope. Page, | 409 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| FROM JERUSALEM, VIA BETHLEHEM AND POOLS OF SOLOMON, TO HEBRON. | |

| Rachel’s Tomb—Bethlehem—Ruth and Boas—David the Shepherd Lad—Cave of the Nativity—Pools of Solomon—Royal Gardens—The Home of Abraham—Abraham’s Oak—Abraham’s Mummy. Page, | 414 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII.xix | |

| FROM DAN TO BEERSHEBA. | |

| Palestine—Its Situation—Its Dimensions—Its Names—Its Topography—Its Climate—Its Seasons—Its Agriculture—Its People—The Pleasure of Traveling through Palestine. Page, | 426 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| JERUSALEM. | |

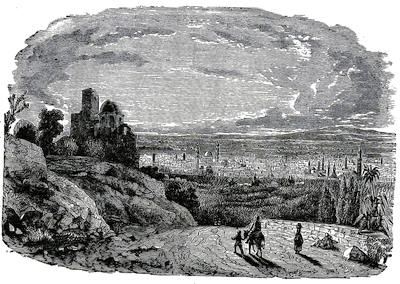

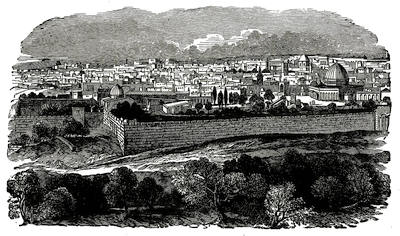

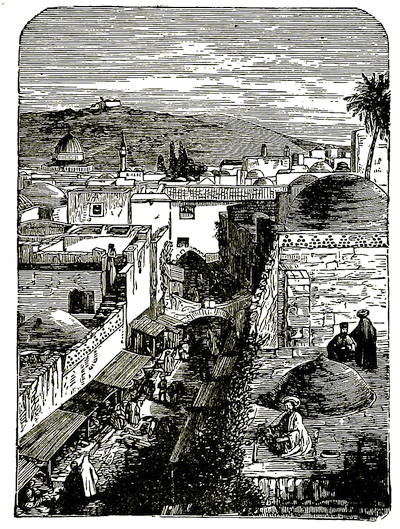

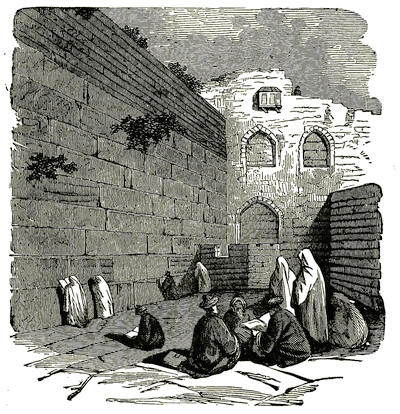

| Approaching Jerusalem—Coming Events—Dreams—Light Breaks In—Serenade—Zion, the City of God—Prayers Answered—Gratitude—A Vision of Peace—Blighted Fig-Tree—Still a Holy City—Prominence of Jerusalem—Its Influence among the Nations—A Melted Heart—Tents Pitched—Walk About Zion—Situation of the City—Its Walls—Its Gates—Afraid of Christ—Crossing the Kedron—Tomb of Virgin Mary—Gethsemane—What it Means, What it Is, and How it Looks—Superstitious Monks—Jerusalem Viewed from the Mount of Olives—Architecture of the City—Prominent Objects—Entering the City—Its Streets—Its Population—Jewish Theologues—Remaining Portion of Solomon’s Temple—”Wailing Place” of the Jews—Kissing the Wall—Weeping Aloud—Fulfillment of Prophecy—Only One Conclusion. Page, | 445 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

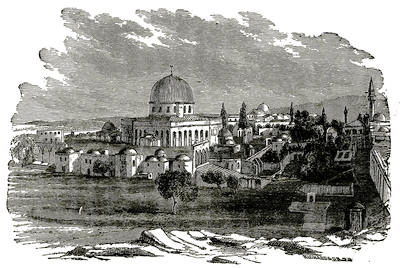

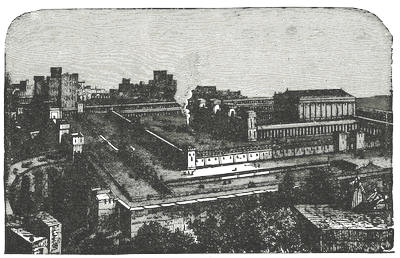

| JERUSALEM CONTINUED—MOSQUE OF OMAR. | |

| Haram Area—Its Past and Present—Wall—Gates—Stopped at the Point of Daggers—Legal Papers and Special Escort—Mosque of Omar—Its Exterior and Interior—A Great Rock Within—History and Legends Connected with the Rock—Mohammed’s Ascent to Heaven—Place of Departed Spirits—Their Rescue—Ark of the Covenant—Golden Key. Page, | 467 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| IN AND AROUND JERUSALEM. | |

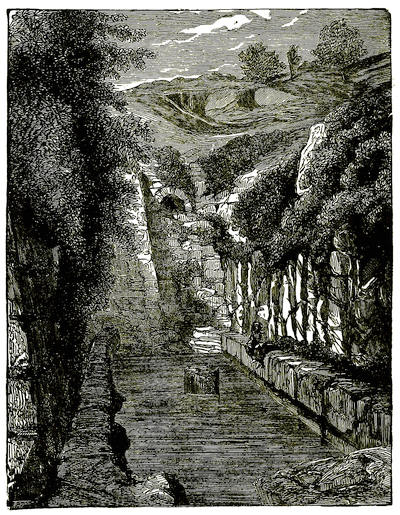

| Church of the Holy Sepulchre—Peculiar Architecture—Strange Partnership—The Centre of the Earth—The Grave of Adam—Unaccountable Superstitions—An Underground World—Pool of Siloam—Kedron Valley—The Final Judgment—Tomb of the Kings—Valley of Hinnom—Lower Pool of Gihon—Moloch—Gehenna—Upper Pool of Gihon—Calvary—The Savior’s Tomb. Page, | 479 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| EGYPT. | |

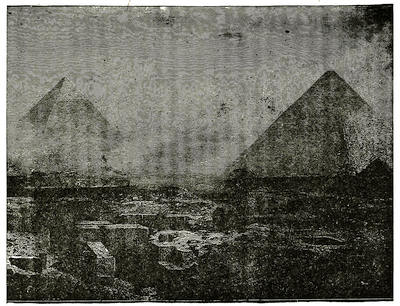

| Jaffa—Its History and its Orange Orchard—On the Mediterranean—Port Said—Suez Canal—The Red Sea—Pharaoh and his Host Swallowed Up—From Suez to Cairo—Arabian Nights—Egyptian Museum—Royal Mummies—A Look at Pharaoh—A Mummy 5,700 Years Old—A Talk with the King—Christmas-Day and a Generous Rivalry—Donkey-Boys of Cairo—Wolves around a Helpless Lamb—Johnson on his Knees—Yankee Doodle—The Nile—The Prince of Wales—Pyramid in the Distance—Face to Face with the Pyramid of Cheops—Ascending the Pyramid—Going in it—Johnson Cries for Help—The Sphinx, and what it is Thinking about. Page, | 495 |

| CHAPTER XLIII.[xx] | |

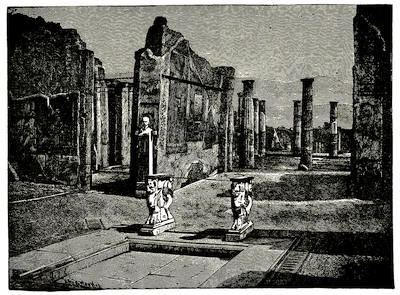

| A BURIED CITY—POMPEII. | |

| Long Shut Out of Civilization—Four Days in Gehenna—Paul’s Experience Co-Incides with Ours—Dead—Buried—A Stone Against the Door—Raised from the Grave—Under an Italian Sky—”See Naples and Die”—Off for the City of the Dead—Knocking for Entrance—Earthquake—Re-Built—Location of the City—Boasted Perfection—City Destroyed by a Volcano—Vivid Description by an Eye-Witness—Rich Field for Excavation—What Has been Found—Returns to Get Gold—Poetical Inspiration—Pompeii at Present—Mistaken Dedication. Page, | 515 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| VESUVIUS IN ACTION. | |

| As it Looks by Day and by Night—Leaving Naples—First Sight of Vesuvius—Description—The Number of Volcanoes—Off to See the Burning Mountain—A Nameless Horse—Respect for Age—Refuse Portantina—Mountain of Shot—A Dweller in a Cave—A Slimy Serpent for a Companion—Jets of Steam—Vulcan’s Forge—Exposed to a Horrible Death—Upheavals of Lava—Showers of Fire—Fiery Fiends—Winged Devils—Tongue of Fire—A Voice of Thunder. Page, | 526 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| ROME—ANCIENT AND MODERN. | |

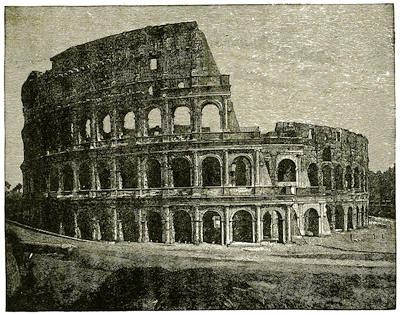

| The Mother of Empires—Weeps and Will not be Comforted—Nero’s Golden Palace—Ruined Greatness—Time, the Tomb-Builder—Papal Rome—The Last Siege—Self-Congratulations—Better Out-Look—The Seven-Hilled City—Vanity of Vanities—The Pantheon—Nature Slew Him—The Shrine of All Saints. Page, | 535 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| ROME—ITS ART AND ARCHITECTURE. | |

| A Question Asked—Answer Given—Nature as Teacher—Italians as Pupils—Great Artists—The Inferno—The Cardinal in Hell—The Pope’s Reply—A Thing of Beauty—The Beloved—The Transfiguration—Architecture—Marble Men Struggle to Speak—Resplendent Gems. Page, | 544 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

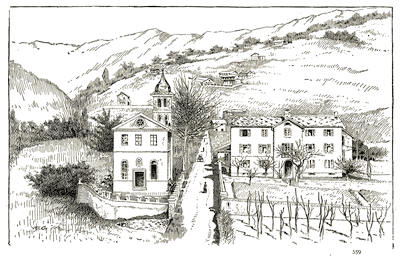

| BAPTIST MISSION WORK IN ITALY. | |

| Why Italy is a Mission-Field—Beginning of the Work—Difficulties—Increase of Forces—Growth of Work—Sanguine Expectations. Page, | 553 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| FROM ROME, VIA FLORENCE TO VENICE. | |

| Peasants—A Three-Fold Crop—Elba, the Exiled Home of Napoleon—Pisa—Leaning Tower—An Odd Burial-Ground—Florence—The Home of Savonarola, Dante, and Michael Angelo—Art Galleries—On to Venice—A Flood—Johnson Excited—Storm Raging—Lightening the Ship—Venice, a Water-Lily—No Streets but Water—No Carriages but Gondolas—Shylocks. Page, | 563 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| COLORED PLATES. | Page. |

| The River Jordan, where it is supposed Christ was baptised, | 380 |

| Vesuvius in Action, | 526 |

| MAP. | |

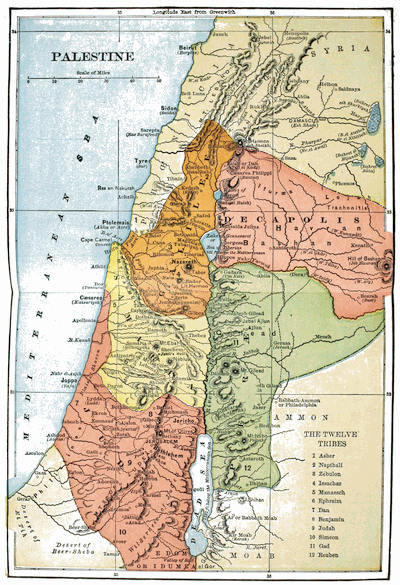

| Palestine—Time of Christ, | 250 |

| WOOD ENGRAVINGS, PHOTO-ENGRAVINGS, ETC. | |

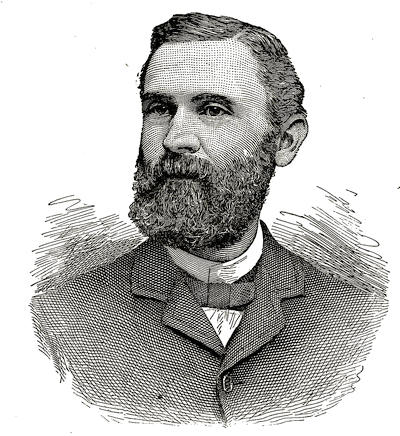

| Steel Plate of the Author—Frontispiece, | |

| Clarence P. Johnson, | 40 |

| Burns’ Cottage, | 42 |

| Burns’ Monument, | 45 |

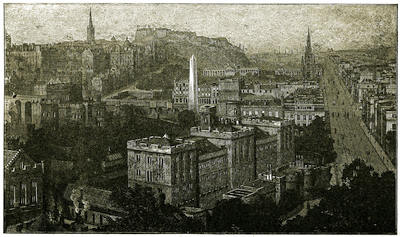

| Edinburgh, | 48 |

| Scott’s Monument, | 51 |

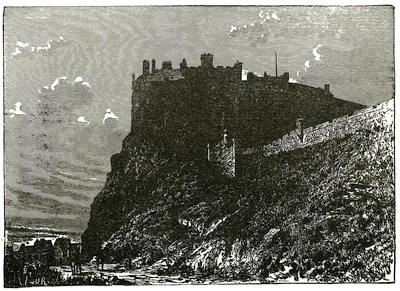

| Edinburgh Castle, | 53 |

| Abbotsford, | 76 |

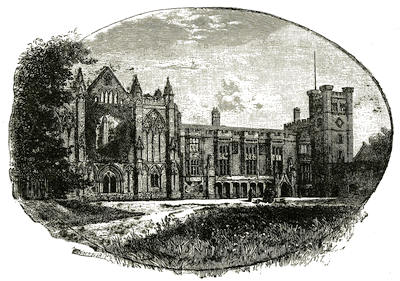

| Melrose Abbey, | 78 |

| Newstead Abbey, | 94 |

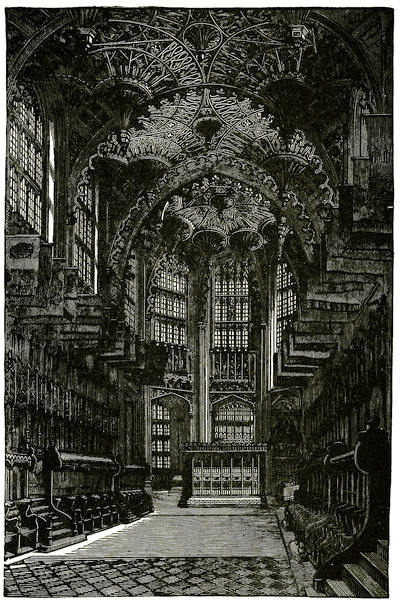

| Chapel of Henry VII, Westminster Abbey, | 104 |

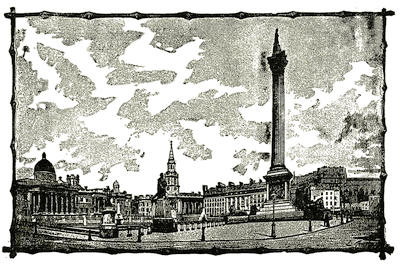

| Nelson’s Monument, | 106 |

| The House of Parliament, | 109 |

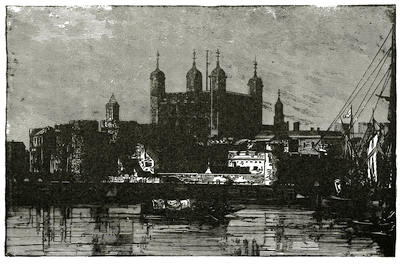

| The Tower of London, | 112 |

| St. Paul’s Cathedral, | 115 |

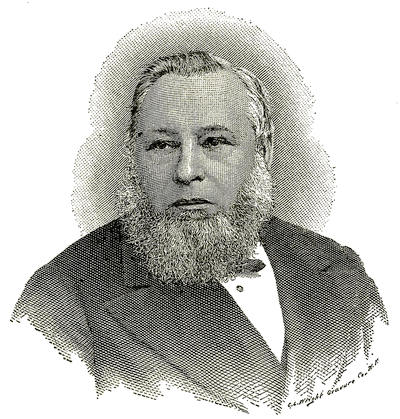

| Chas. H. Spurgeon, | 120 |

| Bunyan’s Cottage, | 129 |

| Edward Parker, | 132 |

| Queen Victoria, | 144 |

| Windsor Castle, | 146 |

| The Home of Shakespeare, etc., (six pictures,) | 148 |

| Strasburg Cathedral, | 158 |

| View on the Rhine, | 164 |

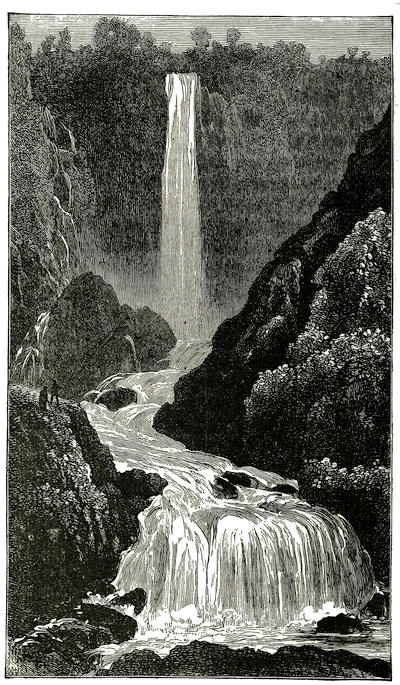

| Giessbach Falls, | 192 |

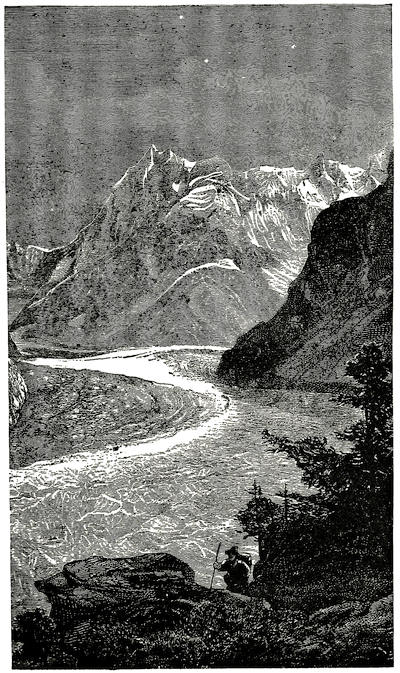

| A Glacier in Switzerland, | 197 |

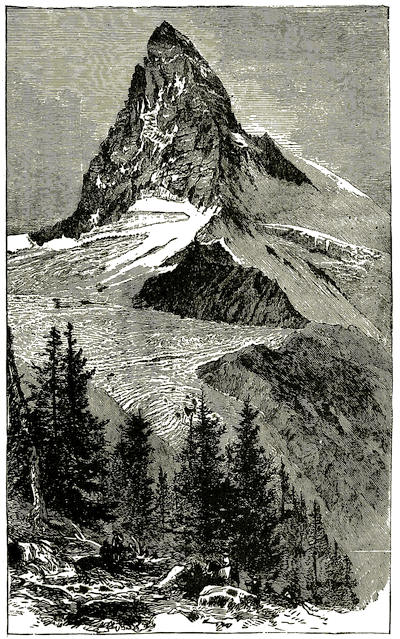

| Among the Peaks, | 202 |

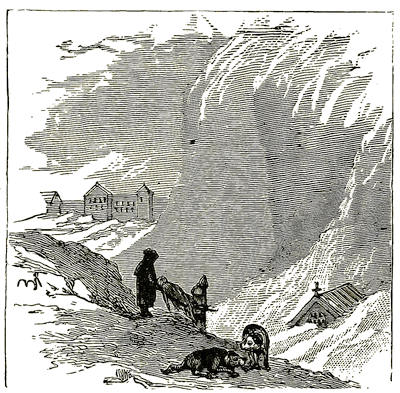

| Hospice in the Alps, | 208 |

| Swiss Mountains, | 211 |

| The Belvidere, Vienna, | 221 |

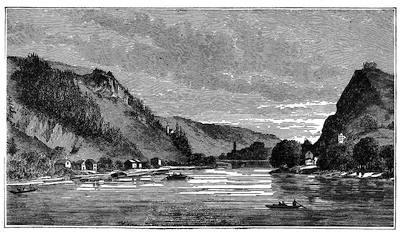

| The Danube, | 224 |

| Castle on the Danube, | 226 |

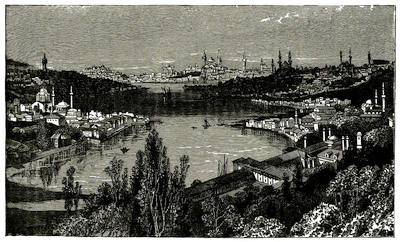

| Constantinople, | 228 |

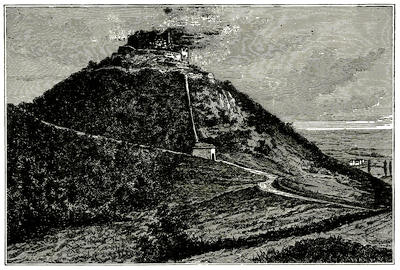

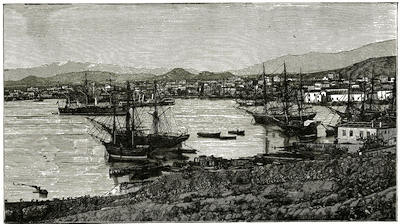

| Modern Athens, | 231 |

| The Acropolis, | 233 |

| The Parthenon of the Acropolis, | 234 |

| The Acropolis of Athens as it was, | 235 |

| Turkish Lady,[xxii] | 243 |

| Island of Patmos, | 247 |

| Cedars of Lebanon, | 263 |

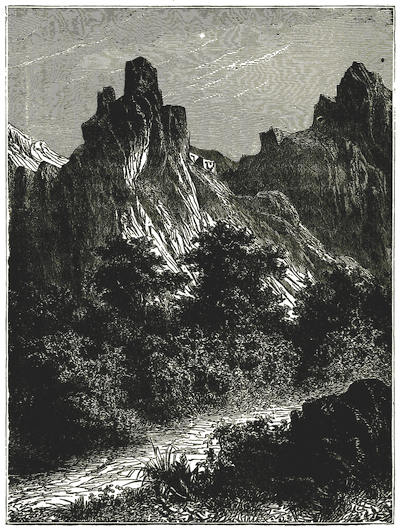

| Ruins of Baalbek, | 274 |

| Damascus, | 278 |

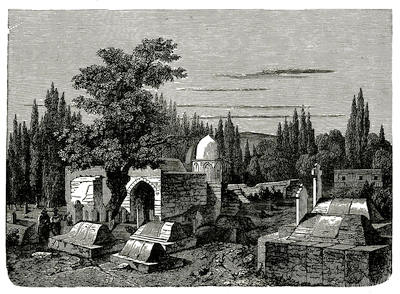

| Tombs of the Caliphs, | 290 |

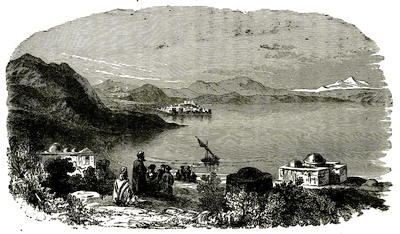

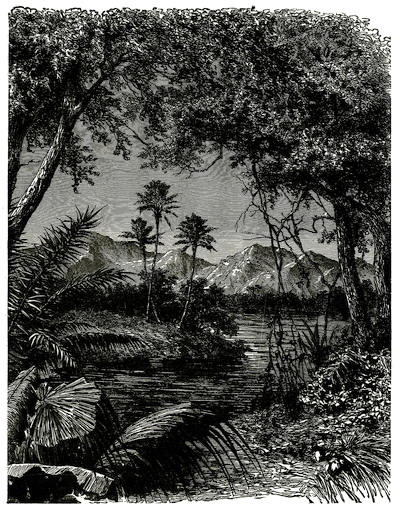

| Sea of Galilee, | 313 |

| Palms in Bush Form, | 321 |

| Priest of the Greek Church, | 325 |

| Vale and City of Nazareth, | 330 |

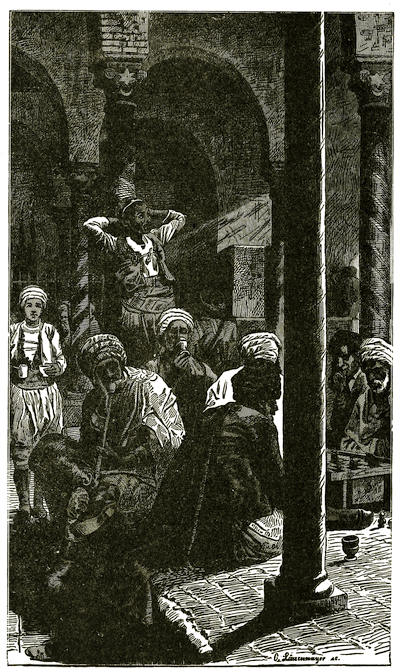

| Interior of a Caravansary, | 338 |

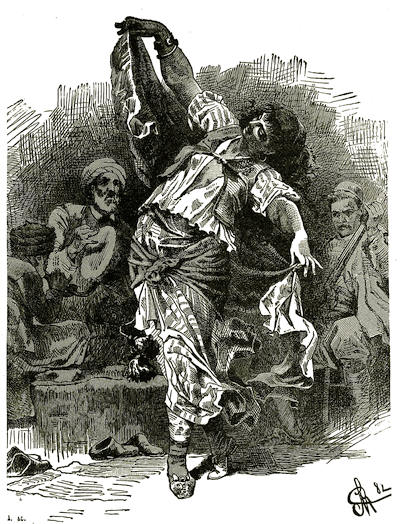

| Dancing Girl, | 341 |

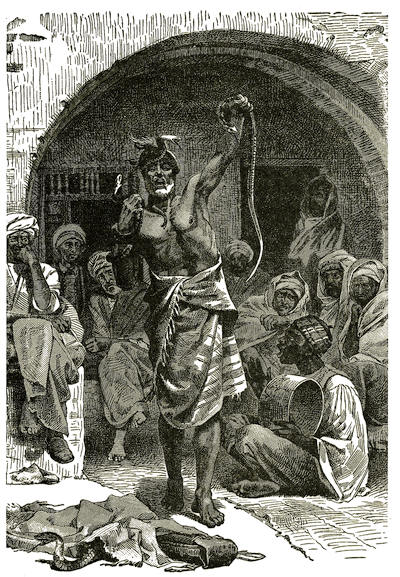

| Snake Charmer, | 343 |

| Ancient Sheep Fold, | 344 |

| Mt. of Olives, | 348 |

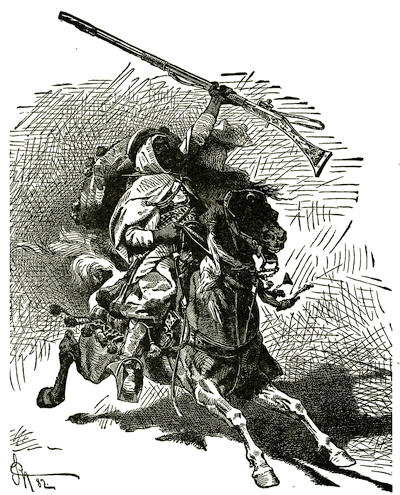

| An Arab Horseman, | 350 |

| A Bedouin, | 352 |

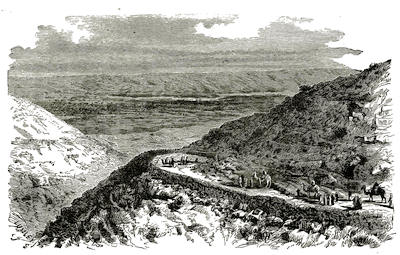

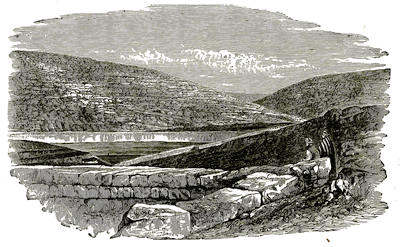

| View on the Road from Jerusalem to Jericho, | 356 |

| Ford of the Jordan, | 391 |

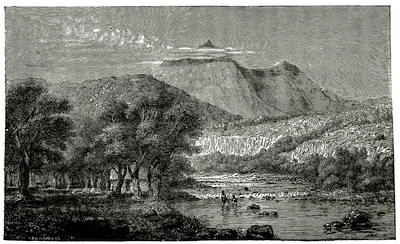

| View in the Valley of the Jordan, | 395 |

| The Dead Sea, | 399 |

| Lot’s Wife, | 402 |

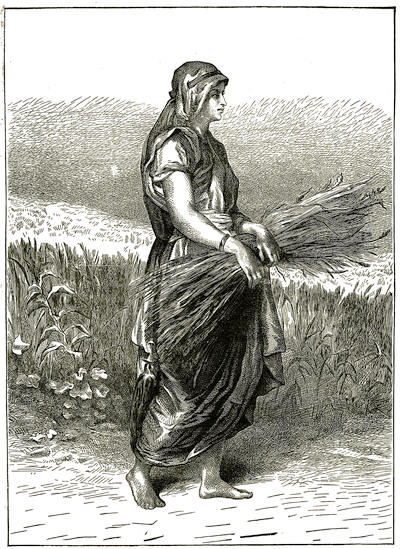

| Ruth, | 415 |

| Cave of the Nativity, | 418 |

| Bethlehem, | 420 |

| Pools of Solomon, | 423 |

| Mosque of Hebron, | 424 |

| Government Guards, | 438 |

| Jerusalem, | 448 |

| Hills and Walls of Jerusalem, | 450 |

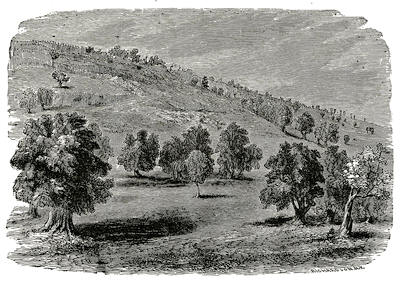

| Old Olive Trees in Gethsemane, | 455 |

| Street in Jerusalem, | 459 |

| Wailing Place of the Jews, | 461 |

| Mosque of Omar, | 470 |

| Solomon’s Temple as it was, | 474 |

| Holy Sepulchre, | 483 |

| Pool of Siloam, | 486 |

| Tombs of the Kings of Judah, | 489 |

| Burial of Christ, | 492 |

| The Castle of David and Jaffa Gate, | 497 |

| An Egyptian, | 502 |

| Donkey Boys of Cairo, | 507 |

| Pyramid and Sphinx, | 509 |

| Pompeii, Street of Cornelius Rufus, | 517 |

| Climbing Mt. Vesuvius, | 528 |

| Colosseum of Rome, | 537 |

| John H. Eager, | 555 |

| Baptist Chapel at Pellice, Italy, | 559 |

| Leaning Tower of Pisa, | 565 |

CHAPTER I.

OFF FOR NEW YORK.

Preparations—A Prayer and a Benediction—An Impatient Horse and a Run for Eternity—Strange Sceptre and Despotic Sway—Beauty in White Robes—Approaching the Metropolis—Business Heart of the New World—A Bright Face and a Cordial Greeting—An Hour with the President—More for a Shilling and Less for a Pound—A Stranger Dies in the Author’s Arms—Namesake—Prospects of Becoming a Great Man—A Confused College Student—The Hour of Departure—Native Land.

PREPARATIONS for the trip were completed when the week ended. Sunday, with its sweet privileges and solemn services, came and went. Mother and I knelt and prayed together. Rising to our feet, she looked up through her tears and smilingly said, “Son, the Lord has given me strength to bear the separation. ‘Go, and ‘God be with you till we meet again.’”

Monday morning, as the hands on the dial plate point to seven, Johnson and I seat ourselves in a carriage which is drawn by a horse whose path is steel, whose heart is fire, and whose speed is lightning. This impatient steed stands champing his bit, and when the word is given he starts on his long journey. At one bound he leaps the majestic river, and on, on he rushes as if he fears eternity will come before he reaches his journey’s end. After traveling only a few hours, we run into a[24] blinding snow-storm which reminds us that Winter still wields his icy sceptre, and rules with despotic sway. This storm continues for hours; in truth, it lasts until apparently the whole earth is wrapped in a mantle of white, and until the majestic mountains of Pennsylvania seem to rise up in their virgin purity to kiss the vaulted sky.

Washington, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, as seen in their white robes, are more beautiful than ever. Winter’s frosty breath has not chilled their blood. They are filled with energy and throbbing with life. From Philadelphia to New York, there is almost one continuous string of cars on each track. Along here our fiery steed sometimes runs sixty miles an hour.

Long before we reach the metropolis, the shadows of the sombre evening have shut out the light of day. As we enter this great city, it looks as if a thousand times ten thousand lamps are all trimmed and burning. New York is a marvelous city.

As much time as I have spent here, I never cease to wonder at it. Who could walk these streets without wondering at the miles of granite buildings, all joining each other and towering up from seven to twelve and fourteen stories high; at the broad sidewalks crowded from six o’clock in the morning until ten at night with one ceaseless stream of humanity; at the people rushing along at a breakneck speed, as if they were going to great fires in different parts of the city.

Notwithstanding the double-tracked elevated[25] railway and the double-tracked horse-cars, New York can not furnish transportation for the people. She will, I think, soon be compelled to arrange for an underground railway—this is a necessity. New York is the business heart of the New World. Every American loves it. It is his pride at home, his boast abroad.

At Temple Court I receive my mail, and meet my friend, Dr. H. L. Morehouse, corresponding secretary of the Baptist Home Missionary Society. As usual, his face is bright and his greeting cordial. He is planning great things for God, and expecting great things of God. Few men have done more to honor God and build up the Baptist cause in America than Henry L. Morehouse.

A pleasant hour is spent with Dr. Norvin Green, President of the Western Union Telegraph Company. His reminiscences of European travel are rehearsed. He says that in London one can buy more for a shilling and less for a pound than in any other place on earth. President Green gives me a letter to his European representative, and kindly extends other courtesies that are duly appreciated.

After attending to banking business and securing our ocean passage, we decide to run over to New Haven and spend a few days with some special friends. The double railroad track between New York and New Haven is constantly in use.[26] When about half way between the two cities, our engineer spies a handsomely dressed gentleman walking on the other track, and going in the same direction that we are going. A train is coming facing the gentleman. Unconscious of the presence of more than one train, he steps from one track to the other, just in front of our engine. Seeing the danger, both engineers try to stop their trains, but do not succeed. Both blow their whistles at the same time, but the walker, thinking all the noise is made by one train, pays no attention. Crash! Our engine strikes the man, and throws him twenty feet from the track. The trains stop. The passengers gather around the unfortunate man. The blood is oozing from his ears and nostrils. I take his head on my shoulder and raise him up to get air. He struggles—gasps for breath—and all is over. A letter in his pocket indicates his name and residence.

A carriage is waiting for us at New Haven. On reaching there, we are driven at once to the happy home of Mr. W. G. Shepard, who forthwith presents me to Master Walter Whittle Shepard. This important character is only twelve months old, but is full of life and promise. If he combines the sweet spirit and graceful manners of his mother with the strong character and bright intellect of his father, I believe he will make a great and useful man notwithstanding the fact that he bears the author’s name.

New Haven, with her one hundred thousand souls and great manufacturing interests, with her parks and colleges, with her broad streets and lordly elms, is one of the prettiest cities on the American continent.

When we retired last night, the snow was falling thick and fast; but we awoke this morning to find that God had snatched a beautiful Sabbath day from the bosom of the storm.

Mark Twain is in New Haven. In the course of a lecture delivered here, he said: “A certain college student got the words theological and zoological confused—he did not know one from the other. In talking to a friend, this collegian said: ‘There are a great many donkeys in the Theological Garden.’”

My stay in New Haven has been as pleasant as a midsummer dream, and seemingly as short as a widower’s courtship. But we must now return to New York. In less than three hours we will leave by the State Line, on “The State of Indiana,” for Glasgow, Scotland. And now that the time of my departure has come, I find myself breathing a prayer to God, asking that He will direct my course; that He will guide my footsteps; that in all my wanderings He will keep me from danger and death; that He will finally bring me back in health and safety to the land of my birth, to the friends of my childhood, to those whom I love and who are dearer to me than[28] life itself. And so may it be. More heartily than ever before, I can say:

“My native country! thee,

Land of the noble free,

Thy name I love:

I love thy rocks and rills,

Thy woods and templed hills;

My heart with rapture thrills

Like that above.”

CHAPTER II.

ON THE HIGH SEAS.

A Difficulty with the Officers of the Ship—A Parting Scene—Danger on the Atlantic—A Parallel Drawn—Liberty Enlightening the World—Life on the Ocean Wave—Friends for the Journey—The Ship a Little World—A Clown and his Partner—Birds of a Feather—Whales—Brain Food—Storm at Sea—A Frightened Preacher—Storm Rages—A Sea of Glory—Richard Himself Again—Land in Sight—Scene Described—Historic Castle—Voyage Ended—Two Irishmen.

STEPPING on board the steamship State of Indiana, I say to the purser: “Sir, I am from the West; I want elbow-room. Can’t you take away these partitions and turn several of these compartments into one?” He replies: “You are now from the West, but you will soon be from this ship, unless you keep quiet.” From this remark I see at once that the fellow is a crank, and I will either let him have his own way or give him a whipping. I choose the former; so we shake hands over the bloody chasm—or, I should say, over the briny deep.

I can never forget the scene that takes place at the wharf. The hour for departure has arrived. Hundreds of people have gathered around the vessel. As the last bell rings, there is hurrying to and fro. Friend leaving friend; husband kissing wife; fathers and daughters, mothers and sons,[30] mingling their tears together, as parents and children take their last fond embrace of each other. Ah! There are streaming eyes and heavy hearts. As the vessel moves off, one sees the throwing of kisses, the waving of hats and handkerchiefs. But we are gone. Tear-bedimmed eyes can no longer behold the forms of loved ones. I dare say that many of these partings will be renewed no more on this earth.

One hazards very little in committing himself to the winds and waves of the Atlantic when he is on a goodly vessel, wisely planned and skillfully put together; when the sea-captain is faithful and experienced, and understands the workings of the mariner’s compass and the position of the polar star. But my very soul is stirred within me when I think of the thousands and tens of thousands who are sailing on life’s dark and tempestuous ocean without a chart or compass; without a rudder to steer or a hand to direct them; without the light from the Star of Bethlehem to guide them over the trackless waters to the Haven of Rest. They came from nowhere! They see nothing ahead of them save the rock-bound coast of eternity, beset with false lights which are luring them on to the breakers of death and the whirlpool of despair. From the bottom of my heart do I thank God for the “Old Ship of Zion,” planned by Divine Wisdom, freighted with immortal souls, guided by the Star of Hope, commanded by Jesus Christ, bound for the Port of Glory!

As we leave New York, the Bartholdi Statue on Bedloe’s Island is one of the last things we behold. This statue has been justly called “the wonder of the century,” and one feels a national pride in the thought that this statue, rising three hundred feet in the air, her right hand lifting her torch on high—that this statue, the wonder of the age, is a fit emblem of the country to which it belongs—it is Liberty enlightening the world!

I can not pause here to speak of the deep, strange and strong impulses that stir one’s soul as he sees his native land fade from view. I must, instead, proceed to tell the reader something about

“A Life on the ocean wave,

A home on the rolling deep,

Where the scattered waters rave

And the winds their revels keep.”

The first few days, if the sea is calm and quiet, and so it is with us, are spent in forming new acquaintances. No one wants an introduction to any one. Everybody is supposed to know everybody else. A hearty hand-shake, a friendly look of the eye, and you are friends for the journey. And I dare say that many who here meet will be firm friends for the journey of life. The company on board the ship is a little world within itself, representing almost every phase of human life, from the lowest to the highest. Here a statesman, there a philosopher; here a musician, there[32] an artist. We have one wonderful fellow on board, who is here, there, and everywhere. He is anything, everything and nothing. He evidently has more life in his heels than brains in his head, and more folly on his tongue than reverence in his heart—a pretended musician, who has decidedly a better voice for eating soup than for singing songs. And it comes to pass that a certain small boy follows the example of this clown, and the two together make things lively and thoroughly uncomfortable for the rest of the party.

Naturally enough, after these acquaintances are formed, birds of a feather flock together. The Rev. Dr. Malcom MacVicar, Chancellor of the MacMaster University of Toronto, and his highly cultivated lady, are among our fellow-passengers. I first met the Doctor some years ago, when in Canada. He is an author of considerable note. For twenty-five years previous to his going to Canada, he was probably the most conspicuous figure in the educational circles of New York State. The University over which he is now called to preside is a Baptist institution with a million dollars endowment. Although raised to high position and crowned with honors, Doctor MacVicar is as humble and unassuming as though he were in the lowliest walks of life. Prof. Honey, of Yale University, places his wife under my care. Mrs. Honey is a lady of lovely character and superior attainments. Those whom I have mentioned, together with two physicians from Indiana,[33] and Rev. Mr. Smith from Canada, form a little party somewhat to ourselves, though we try not to appear clannish.

The passengers are occasionally attracted by whales, and are much interested in watching them. Frequently two or three may be seen following the vessel for miles and miles at a time, to get such food as may be thrown overboard. Then they strike out ahead of us, or to one side, chasing each other through the water. These monsters of the deep remind me of a former class-mate, who was noted more for genial nature than for strong intellect. One day, while the class in chemistry were reciting, he said:

“Professor, I understand that fish is good brain-food. Is it true?”

The teacher replied: “Yes, I am disposed to think there is some truth in the statement.”

“I am glad to know that, Professor, I am going to try it. How much do you think I ought to eat?”

“Well, Sir,” responded the sarcastic professor, “I should recommend at least half a dozen whales.”

I am sure, however, that when I last saw the student in question he had not begun the eating of fish.

The fourth day is stormy and the sea rough. The women and children are sick, very sick. The men are thoroughly prepared to sympathize with them. They all lose their sea-legs. The vessel[34] is turned into a hospital. It is really amusing to hear the different expressions from these afflicted sons of Adam.

One fellow, amid his heaving and straining, says: “I am not ‘zac’-ly sea-sick, but my stomach hurts me mightily.”

Another, in like condition, says: “If they would stop the ship only five minutes I would be all right.”

In the midst of the severest agony, an old gentleman ejaculates something like this: “I left my children and loved ones at home, and I expect to return in four months; but I would stay in Europe four years, if I knew there would be a railroad built across in that time.”

I did not hear this myself, but it is said of one clergyman on board that amid the fierceness of the storm he became exceedingly uneasy. Wringing his hands, and approaching the chief officer, he exclaimed: “O Captain, Captain, is there any danger of d-e-a-t-h?” The captain replied: “Would that I could give you some encouragement; but, my Reverend Sir, in five minutes we shall all be in Heaven.” At this, the distressed preacher clasped his hands and cried aloud, “God forbid!” A United States Minister on board said that any one who would cross the ocean for pleasure, would go to hell for amusement.

For five days the sea rages, and the vessel rolls and labors and groans. Looking out over the waters, I see ten thousand hills and mountains,[35] each crowned with white surf, which in the distance looks like melting snow. Between these mountains there are deep gorges and broad valleys. A moment later the mountains and valleys exchange places. Now on the crest of a wave, the vessel is borne high in the air, and now she drops into a yawning gulf below, coming down first on one side then on the other. Now and then she pitches head-foremost, reeling and staggering like a drunken man.

But, as usual, calm and quiet follow the storm. The sea is now as placid as a lake. The sun is going down, apparently to bathe himself in a sea of glory. In a few minutes the gleaming stars will look down to see their bright faces reflected in the water. The sick are restored to health, the staggering walk is gone, and “Richard is himself again.”

We were in sight of land almost the whole of yesterday. About twilight last evening, we viewed the western coast of “bonnie Scotland.” I arose at an early hour this morning, to find our stately craft smoothly gliding on the placid waters of the river Clyde. It is a picture worthy of the artist’s brush—a scene well calculated to inspire every emotion of the poet’s soul.

On the north side of the majestic river, there is a sodded plain, broad and unbroken, gradually rising from the water’s edge. As we view this wooded landscape o’er, we see, here and there, farmhouses, which are as picturesque and beautiful as[36] they are quaint and old, with the smoke from their ivy-covered chimneys coiling up and ascending on high like incense from the altar of burnt offering. Turning our eyes southward, we behold, hard by the stream, a long chain of towering mountains, whose gently sloping sides are carpeted with green grass, and girt around with budding trees. The heavy rain-drops on the grass and leaves are sparkling in the light of the new-risen sun. The mountains are echoing the merry tune which comes from the whistling plowman on the opposite shore. Now, between these two prospects, on the broad and unruffled bosom of this flowing river, our heavily-laden vessel, as though she were weary because of her long journey, moves slowly, gracefully, noiselessly, with the stars and the stripes proudly streaming from her mast-head. Indeed so motionless and queenly is our goodly vessel in her onward course, that she is apparently standing still while the mountains and plains are passing in review before her.

A little farther up the stream, we see Dumbarton Castle standing in the river. This historic rock measures a mile in circumference, and rises three hundred feet above the water. This castle was at one time the prison of Sir William Wallace, and afterwards the stronghold of Robert Bruce. From here on to Glasgow the Clyde is lined on both sides with iron-foundries and ship-building yards.

The voyage ends at Glasgow. The passengers[37] are glad once more to press terra firma under their feet. I would write something about Glasgow, but I am like the more hopeful one of two Irishmen who went to America. Landing in New York, they started up town. They had gone only a few paces, when one of them saw a ten dollar gold piece lying on the sidewalk, and stooped to pick it up. The other said: “Oh, don’t bother to get that little coin; we will foind plenty of pieces larger than that.”

CHAPTER III.

THE LAND OF BURNS.

English Railway Coaches—Millionaires, Crowned Heads, and Fools—A Conductor Caught on a Cow-catcher—Last Rose of Summer—Off on Foot to the Land of Burns—Appearance of Country and Condition of People—Destination Reached—Doctor Whitsitt and Oliver Twist—The Ploughman Poet—His Cottage—His Relics—His Work and Worth—His Grave and Monument—A Broad View of Life.

I AROSE this morning at an early hour, and, after partaking of a hearty breakfast, I at once repair to the Grand Central Depot in Glasgow where, a few minutes later, I seat myself in an English railway car. These cars are, of course, made on the same general plan as ours, yet they are in some respects quite different. The coaches are of about the same length as those used in America, but not so wide by eighteen inches or two feet. Each coach is divided into five compartments, each being five and one-half or six feet long. Each of these compartments has two doors, one on either side of the car, also two seats. Persons occupying these different seats must face each other, so one party or the other must ride backwards. They have no water or other conveniences on the train, as we Americans are accustomed to; no bell-rope to pull, in case of accident; no baggage-checks—each passenger[39] must look after his own baggage. As for myself, I have no baggage, save what I can carry in the car with me. They have first, second, and third-class compartments, the fare per mile being four, three, and two cents respectively. I have examined closely, and can not detect one particle of difference between the first and second-class compartments, either one being fully as good as our first-class car. The English first and second-class compartments are slightly superior to the third-class. It is a saying among the Europeans that only millionaires, soreheads (crowned heads), and fools ride first-class. Being neither a millionaire nor a crowned head, and, as I am unwilling to be classed as a fool, I always take third-class passage.

I believe in talking, asking questions, and exchanging ideas with every man I meet, be he high or low, rich or poor. So, while standing at the depot this morning, amid a great crowd of people, looking at the engines, I remark to a pleasant-looking conductor standing near me, that there is quite a difference in the engines used in this country and those used in America. He wants to know what that difference is. I tell him that our engines have cow-catchers before them and his has none. “A cow-catcher,” says he, “and what is that?” I explain to him that a cow-catcher is an arrangement fastened on in front of the engines to remove obstructions from the road, to knock cows from the track, etc. “Ah, indeed! We never need those in this country, and can you tell me,” he continues, “why we do not need them?” “Well, sir,” I reply, “I can see only one reason.” “And what is that, pray?” I answer, “It must be, sir, that you do not run fast enough to overtake a cow.” This creates quite a laugh at the conductors expense, though none seems to enjoy it more heartily than he. Just at this moment, the train starts, and I am off for Ayr, some forty miles away.

CLARENCE P. JOHNSON.

As I step from the train in Ayr, the hack-drivers gather around me like bees around the “Last Rose of Summer.” “Carriage, carriage, sir?” they cry. “I’ll be glad to show you through the city, and take you to Burns’ Monument—carriage, carriage?” Tipping my hat, I reply, “No, gentlemen, I will take a carriage some other time, when I have more leisure. I prefer walking to-day, as I am in a great hurry.” So, each with a cane in his hand and a portmanteau strapped on his back, Johnson, my pleasant traveling companion, and I set out on foot for “The Land of Burns.”

Luckily, we meet with some intelligent farmers who cheerfully give us much valuable information about the country. They, in turn, ask many questions concerning far-off America. Land in this part of Scotland is worth from two hundred to three hundred dollars per acre, and the annual rent is twenty to twenty-five dollars per acre. Most of the land in this country is owned by a few “lords” and “nobles,” and the “common people” are in bondage to them. They are in poverty[42] and rags, as might naturally be expected from the exorbitant rents which they have to pay.

“Man’s inhumanity to man,

Makes countless millions mourn.”

The principal crops raised by the farmers of this country are wheat, oats, rye, barley and Irish potatoes. They grow no Indian corn. They do not know what corn-bread is—many of them have never heard of it.

BURNS’ COTTAGE.

After a walk of an hour and a half through a most charming country, we reach our destination. I am now sitting in the room where was born Robert Burns who, Dr. Whitsitt says, was the most important personage that the British Isles have produced since the time of Oliver Twist—oh, excuse me, I should have said, since the time of Oliver Cromwell. I would have had it right[43] at first, if that “twist” had not gotten into my mind. This important personage was born 128 years ago. How long this cottage was standing before that time, we do not know; but, as you may imagine, it is now a rude and antique structure. It is built of stone, and the walls are about six feet high. It has an old-fashioned straw or thatched roof and a stone floor. A hundred years ago, this room had only one window. That is only eighteen inches square, and is on the back side of the house. In the time of Burns, the cottage had only two rooms, though some additions have since been made. The entire place is now owned by the “Ayr Burns’ Monument Association,” and the original rooms are used only as a museum, wherein are collected the furniture, books, manuscripts and other relics of the illustrious bard.

I have, for a long time, been somewhat familiar with the history and writings of the “Peasant Poet,” whose birthplace I now visit, and I have often read Carlyle’s caustic essay on Burns. I have just finished reading his life, written by James Currie. I have read, to-day, “The Holy Fair,” “Tam O’Shanter,” “Man Was Made to Mourn,” and “To Mary, in Heaven,” and now, as I sit in the room where this High Priest of Nature first saw light, as I sit at the table whereon he used to write, and view the relics which once belonged to him, I am carried back for a hundred years and made to breathe the atmosphere of the[44] eighteenth century. As I sit within these silent walls, a strange feeling comes over me. I hear, or seem to hear, the lingering vibrations of that golden lyre, whose master indeed is dead, but whose music still finds a responsive echo in every human heart. Robert Burns, the man, was born of a woman but Robert Burns, the poet, was born of Nature! He stole the thoughts of Nature and told them to man. It was believed long ago that Burns was the High Priest, the interpreter, of Nature, and

“Time but the impression deeper makes,

As streams their channels deeper wear.”

The multitudes who hither come, prove by their coming that

“Such graves as his are pilgrim shrines,

Shrines to code nor creed confined—

The Delphic vales, the Palestines—

The Meccas of the mind.”

Some three hundred yards beyond the cottage, we come to the “Burns’ Monument,” beautifully situated on “The braes and banks o’bonnie Doon, Tugar’s winding stream.” A more appropriate location could not have been selected for this monument, as near by are the “Alloway Kirk,” the “Wallace Tower,” the “Auld Mill,” and the “Auld Hermit Ayr,” and other localities rendered famous by the muse of the ploughman poet. I stand on the “Brig o’ Doon” before reaching the keystone of which Meg, Tam O’Shanter’s mare, “left behind her ain grey tail.”

BURNS’ MONUMENT.

From the top of this towering monument, which stands in the midst of a beautiful flower-garden, I for once take a “broad view of life.” With one sweep of the eye, I see the Doon, the Ayr, the Clyde, the ocean! The scene is made more grand and inspiring, more picturesque and beautiful, by the lakes, plains, hills and mountains which lie between, overhang, and tower above, these laughing rivers. Ah! me, how my spirit is stirred! Like Father Ryan, I have thoughts too lofty for language to reach. In describing what I now see and feel, silence is the most impressive language that can be used. Thought is deeper than speech. Feeling is deeper than thought.

CHAPTER IV.

EDINBURGH.

A Jolly Party of Americans—Dim-Eyed Pilgrim—Young Goslings—An American Goose Ranch—Birthplace of Robert Pollok and Mary Queen of Scots—The Boston of Europe—Home of Illustrious Men—A Monument to the Author—Monument to Sir Walter Scott—Edinburgh Castle—Murdered and Head Placed on the Wall—Cromwell’s Siege—Stones of Power—A Dazzling Diadem—A Golden Collar—Baptized in Blood—Meeting American Friends.

WE ARE now in Edinburgh; we have been here some days. On our way from Ayr, we fell in with a jolly party of American gentlemen. The eyes of one grey-haired brother in the crowd are somewhat dimmed with age, though he is unwilling to acknowledge it.

As the train made a graceful curve around a mountain, we came into a large, green pasture where many sheep were grazing. Now, the people of this country feed their sheep on turnips—large, yellow turnips, with the tops cut off. While in this pasture, we saw, some seventy-five or a hundred yards from the road, a great quantity of these turnips scattered over the grass for sheep food. The dim-eyed pilgrim spied the yellow objects and, pointing to them, he enthusiastically exclaimed: “Oh, what a fine lot of young goslings!” Then he added, “There are the goslings, but where are the geese?” I explained that those objects he saw were not “goslings” but turnips, and suggested that the goose was on our train. Before we separated, the two parties became fast friends. We all agreed to throw in and buy our friend a farm, to be known, not as a turnip patch, but as “The American Goose Ranch,” and on this ranch we are to meet the first day of May of each year, to discuss vital questions and living issues pertaining to the life and character of “young goslings.”

EDINBURGH.

Leaving the pasture, we passed the Moorhouse farm, where Robert Pollok, author of “The Course of Time,” was born, in 1798, two years after the death of Robert Burns. We came by Linlithgow, the birthplace of Queen Mary. The majestic ruins of its once proud palace are still standing on a green hillside near the town, as if to impress the passer-by with the mutability of all human greatness and all human grandeur.

In one hour more we had reached the end of our journey. Edinburgh has two hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants, just half the number of Glasgow, and is a magnificent city. It is the pride of every Scotchman. It is called “The Classic City,” “The Bonnie City,” “The Capital City,” “The Monumental City,” and “The Athens of Britain.” I expected to hear it called “The Boston of Europe,” but the people did not seem to think of it. This was the birthplace of Sir Walter Scott, the novelist and poet; the home of Hume, the scholar and historian; of John Knox,[50] the reformer, who never feared the face of man, nor doubted the Word of God; of Thomas Chalmers, the Astronomical preacher from whose pulpit the stars poured forth a flood of light and glory; and it was for a thousand years the home of the Scottish Kings and state officials. It is now the political home of Gladstone, who is perhaps the greatest living statesman, and the home of Drummond, author of “Natural law in the Spiritual World.”

The city is filled with many objects of peculiar interest, only a few of which I will mention. About a hundred years ago, though the people here speak of it as “recently,” the city was greatly enlarged, and I suppose the object of the enlargement was to make room for the monuments and statues. One sees a monument on almost every street-corner, and there is a perfect forest of statuary. These Scotch people are very fond of honoring great men. I am going to leave here to-morrow, for fear they put up a monument to me. They have not said anything about the monument yet, but I notice the police have been following me about for two or three days, as though they thought of something of that sort.

SCOTT’S MONUMENT.

On Princess street, in the prettiest and most romantic part of the city, stands a colossal monument to Sir Walter Scott which was fashioned by one of the world’s greatest artists, and which is said to be one of the most superb structures of the kind ever built. I am quite prepared to believe[51] the statement. In this monument architectural grandeur and artistic beauty are blended in the sweetest and most perfect manner imaginable. Like a sunset at sea, it never becomes monotonous, but is always pleasing. A fit emblem this of Scott himself, in whom a strong character was so gracefully blended with smooth and polished manners. This monument may be painted, but it beggars description.

To me, however, the most interesting object in Edinburgh is the Castle, located just in the centre of the city. The Castle is built on a high rock whose base covers an area of eleven acres. This rock rises to a[52] height of four hundred feet, its summit being accessible only in one place, the other portions of the rock being very precipitous, and, in some places, absolutely perpendicular. The top of the rock presents a level surface, has an area of five acres, and is surmounted by a massive stone wall built close around on the edge of the cliff. On this storm-beaten rock, and within these moss-covered walls, stands the historical Castle, built ten centuries ago. In appearance the Castle is “grand, gloomy, and peculiar.” In his charming poem, Marmion, Scott refers to it thus:

“Such dusky grandeur clothed the night,

Where the huge castle holds its state,

And all the steep slope down;

Whose ridgy back heaves to the sky,

Piled deep and massive, close and high,

Mine own romantic town!”

According to the history of Scotland, which to me is as charming as a story of romance, this Castle has a strange and bloody tale to tell. Here James II was confined, likewise James III. Here “The Black Dinner” was given, and the Douglasses were murdered. Here the Duke of Argyle and the good Montrose were beheaded. Montrose, you remember, is a conspicuous figure in Scottish history. He was loyal to his king and country. He was courageous as a lion, and as true and noble as he was brave. Yet he was tried before a false court, whose verdict was that on the next day he should be put to death, and his head placed on the prison wall. When permitted to reply, Montrose, in his calm and dignified manner, stepped forward and, with his usual boldness, said to the Parliament: “Sirs, you heap more honor upon me in having my head placed upon the walls of this Castle, for the cause in which I die, than if you had this day decreed to me a golden statue, or had ordered my picture placed in the King’s bed-chamber.”

EDINBURGH CASTLE.

In 1650, Cromwell besieged the Castle, for more than two months, without success. This was the home of the beautiful Queen Mary at the time she gave birth to James VI, since whose reign the whole of Great Britain has been ruled by one sceptre.

In what is called “The Crown Room” of the Castle, are “The Stones of Power,” or the “Emblems of Scottish Royalty.” These regalia consist of three articles, the Crown, the Sceptre, and the Sword of State. By a fortunate circumstance, I obtain free access to these royal relics. They are entirely new to me, hence I examine them closely. Thinking perhaps the reader would like to know something of an earthly crown before going home to wear an Heavenly one, I give the following description of this one: The lower part is composed of two circles, the undermost much broader than that which rises above it. Both are made of purest gold. The under and broader circle is adorned with twenty-two precious stones,[55] such as diamonds, rubies, topazes, amethysts, emeralds and sapphires. There is an Oriental pearl interposed between each of these stones. The smaller circle, which surmounts the larger one, is studded with small diamonds and sapphires alternately. From this upper circle two imperial arches rise, crossing each other at right angles, and closing at the top in a pinnacle of burnished gold.

The Sceptre is a slender and an elegant rod of silver, three feet long, gilded with gold and set with diamonds. The Sword of State is five feet long. The scabbard is made of crimson velvet and is ornamented with beautiful needlework and silver.

In the same glass case with the above-named insignia, is a golden collar of the “Order of the Garter,” which collar is said to be that presented by Queen Elizabeth to King James VI when he was created Knight of that Order. In the same case, is also a ruby ring labeled as the coronation ring of Charles I. But enough about

“The steep and belted rock,

Where trusted lie the monarchy’s last gems—

The Sceptre, Sword, and Crown that graced the brows,

Since Father Fungus, of an hundred kings.”

I am having a perfect feast in re-reading the “Heart of Midlothian,” the plot of which is laid in this city. I never had such a thirst for knowledge, nor did I ever enjoy reading so much as[56] now. I make daily visits to the Haymarket, to the old Tolbooth, to Holyrood Palace, to Arthur’s Seat, to the cottage where the Dean family lived, and to many places which have been baptized in blood, and about which Scott’s muse loved to sing.

While in the Waverly Hotel, a few days ago, I chanced to meet Reverends J. K. Pace and W. T. Hundly, Baptist preachers from South Carolina. What a happy meeting! We were together only two days. Theirs was a flying trip, and they had to rush on to London and the Continent without seeing much of “Bonnie Scotland.” We agree to meet in six weeks in London or Paris.

CHAPTER V.

A TRAMP-TRIP THROUGH THE HIGHLANDS.

His Royal Highness and a Demand for Fresh Air—A Boy in his Father’s Clothes—Among the Common People—Nature’s Stronghold—Treason Found in Trust—Body Quartered and Exposed on Iron Spikes—Receiving a Royal Salute—Following no Road but a Winding River—Sleeveless Dresses and Dyed Hands—Obelisk to a Novelist and Poet—On the Scotch Lakes—Eyes to See but See Not—A Night of Rest and a Morning of Surprise—A Terrestrial Heaven—A Poetic Inspiration—A Deceptive Mountain—A Glittering Crown—Hard to Climb—An Adventure and a Narrow Escape—Johnson Gives Out—Put to Bed on the Mountain Side—On and Up—A Summit at Last—Niagara Petrified—Overtaken by the Night—Johnson Lost in the Mountains—A Fruitless Search—Bewildered—Exhausted—Sick.

AFTER a sojourn of ten days, I left Edinburgh, the site of Scottish nobility. While there I heard so much of Dukes and Earls, of Lords and Nobles, of Her Majesty and His Royal Highness, etc., that it became necessary for me to seek some mountain peak where I could get a full supply of fresh air. If there is such a thing, I have a pious contempt for high-sounding titles of honor and nobility, and especially when, as is too often the case, the appellations themselves are of more consequence than the men who wear them. A man may indeed have a great name “thrust upon him,” but greatness itself is not thus attained. I like to see a son inherit his father’s good qualities, and the more of them the better, but as for honors and titles, let him win those for[58] himself. I saw a “Duke” the other day who reminded me of a half-grown boy on the streets wearing his father’s worn-out pants and coat and hat.

Well, as I started out to say, I became so nauseated with these inherited, worn-out, loose-fitting titles of nobility that I determined to leave the rendezvous of “honor,” and get out into the country among the common people. Accordingly I left Edinburgh, a week ago to-day, for an extended tramp-trip through the Highlands. I came first by rail, via Glasgow, to Dunbarton, a ship-building town of 13,000 inhabitants, on the river Clyde. Thence, a pleasant walk of three miles brought me to Dunbarton Castle, which I saw from the steamer as we were coming from America, and which was barely mentioned in a previous chapter. “This Castle,” says the Scottish historian, “is one of the strongest in Europe, if not in the world.” It is, as before stated, a great moss-covered rock, standing in the river, measuring a mile in circumference, and rising nearly three hundred feet high. In the first century of the Christian era, the Romans gained possession of, and fortified themselves in, this Castle. By the treachery of John Monmouth, Sir William Wallace, while on this rock, was betrayed, in 1305, into the hands of the British, who took him to London and struck off his head, after which his body was quartered and exposed upon spikes of iron on London Bridge. A long[59] two-handed sword, once used by Wallace, and other ancient relics of warfare, are shown to the visitor.

From the top of the Castle, one gets a commanding view of the surrounding country. While there, looking northward, I saw Ben Lomond, more than twenty miles away. I could not refrain from taking off my hat to this “Mountain Monarch.” And, as if to return my salute, the clouds just then were lifted, leaving the snow-covered head of the mountain bare for a moment. For this act of civility, I determined to pay His Royal Highness a visit. Hence, with felt hats pulled down over our eyes, with canes in hand, and small leather satchels strapped across our backs, my traveling companion and I set out on foot for the Highlands.

We followed no road, being guided by the river only, which flows from Loch Lomond into the Clyde. The general scenery along this route is nothing unusual; but the river itself is surpassingly beautiful, its water being transparent, and flowing deep, smooth and swift, but silent, between its level green banks.

Just before entering a small town, on the river, called Renton, we met hundreds of girls and young women homeward bound, all wearing sleeveless dresses, and carrying tin buckets. Their dyed hands and arms bespoke their occupation. They were factory girls, employed in the paint works the largest in Scotland. In this town, is a[60] splendid obelisk to Tobias Smollet, the novelist and poet, who was born here in 1721.