| Five Minute Stories | $1.75 |

| More Five Minute Stories | 1.75 |

| Three Minute Stories | 1.75 |

| A Happy Little Time | 1.75 |

| Four Feet, Two Feet, No Feet | 2.75 |

| When I Was Your Age | 1.75 |

| Honor Bright | $1.75 |

| The Armstrongs | 1.50 |

| The Green Satin Gown | 1.50 |

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY THE PAGE COMPANY

———

All rights reserved

———

First Impression, November, 1914

Second Impression, March, 1917

Many of these stories and rhymes appeared originally in the Ladies’ Home Journal, and were signed either with my initials, or with names of characters in my books. Others were adapted by me from the Indian “Hitopadesa,” or “Book of Good Counsel,” and from two anonymous story-books of a bygone generation, long out of print. These are marked “Adapted.”

| PAGE | |

| Johnny and His Sand Box | 1 |

| Monosyllabics | 6 |

| The New Leaves | 10 |

| Grandmother’s Alphabet | 14 |

| The New Leaf | 20 |

| Mr. Hoppy Frog | 26 |

| New Year’s Day in the Wood | 28 |

| The News from Angel Land | 33 |

| The Boastful Donkey | 37 |

| The Cat’s Name | 41 |

| Suppity, Sippity! | 44 |

| [x]Johnny’s Red Shoes and White Stockings | 46 |

| The Foolish Tortoise | 53 |

| The Garden Gate | 56 |

| Little Cat’s Valentine | 59 |

| To My Valentine | 65 |

| March | 67 |

| Something New | 69 |

| Mr. Sparrow’s Bath | 70 |

| Little Girl | 76 |

| How Mr. Peacock Went to the Fair | 78 |

| Little Boy | 83 |

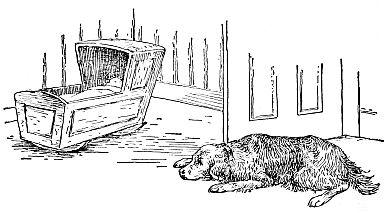

| Faithful Trusty | 85 |

| The Grateful Crane | 88 |

| The King of the Fen | 92 |

| The Swing | 98 |

| The Trees | 100 |

| The Leprechaun | 104 |

| The Deer and the Crow | 109 |

| Little Goldstar | 114 |

| The Broom | 119 |

| The Clever Crows | 121 |

| The John-Betty Table | 125 |

| The Little Gray Doves | 135 |

| Merry Christmas | 138 |

| Christmas Gifts | 142 |

| Church-bells | 148 |

| [xi]The Bird of Light | 151 |

| The Brothers and Sisters | 153 |

| The Pigeons | 155 |

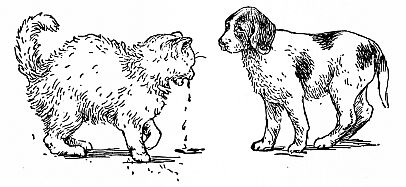

| Pussy and Doggy | 157 |

| Dick’s Family | 159 |

| PAGE | |

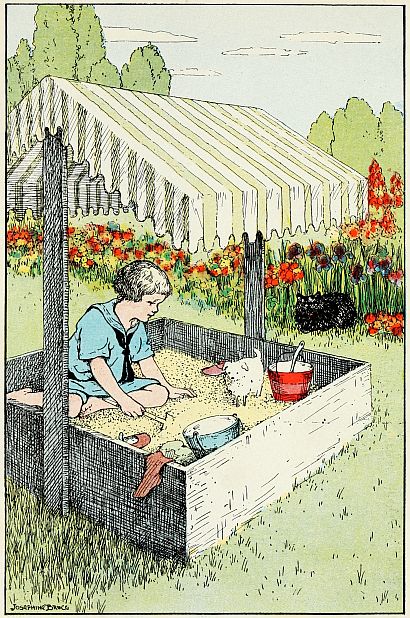

“It is a fine big box, with the sides raised so that Johnny and the sand will not fall out.” (See page 1) |

Frontispiece |

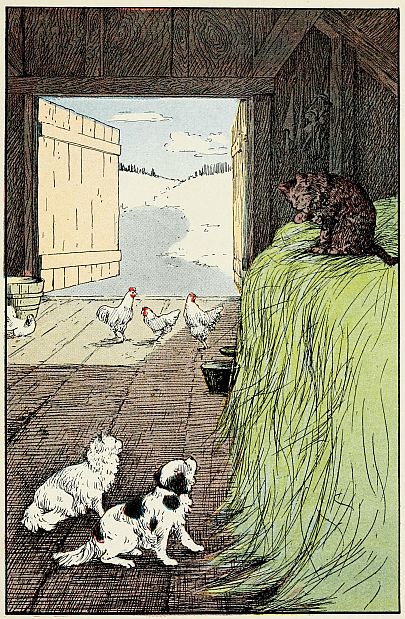

“They found Old Cat in the Barn sitting on a truss of hay, washing herself” |

22 |

“He held them up so that the Boy Over the Fence could see them” |

48 |

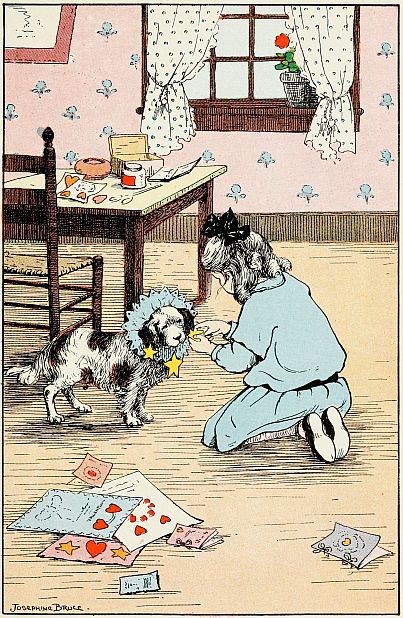

“Then she made two little stars and pasted them on the tips of his ears” |

62 |

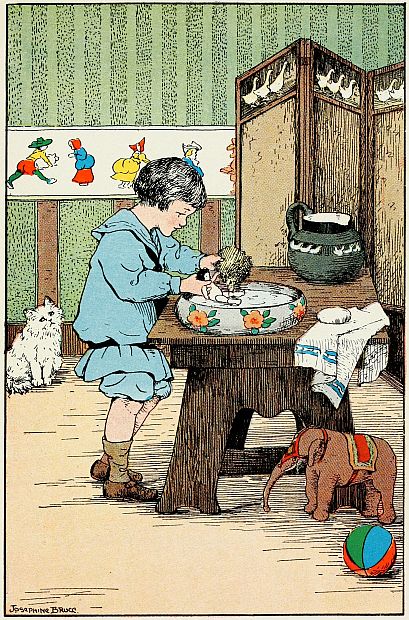

“Now he gave her one in the rosy-posy dish” |

71 |

“The battle was long and fierce on both sides” |

96 |

“Twice one is two, we make our bow to you” |

125 |

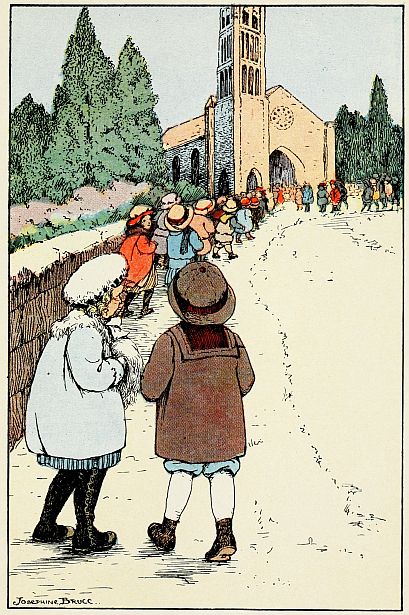

“Now the doors wide open throw, that we into church may go” |

148 |

Johnny’s sand box is in the back yard. It is a fine big box, with the sides raised so that Johnny and the sand will not fall out. The sand is fine and dry, and almost white; it came from the seashore, and sometimes you find a little shell in it.

The things that belong in the sand box (beside Johnny himself!) are the blue tin pail to hold sand, and the red tin pail to hold water, and the shovel, and the rake, and the old kitchen spoon. The things that do not belong there (some of them) are the woolly dog (because the sand gets all into his wool, and then shakes out on the nursery floor, and Maggie says it is a Sight!), and Johnny’s[2] shoes and stockings (he likes to take them off and sift the hot, clean sand between his bare toes), and the neighbors’ cats.

This story is about the cats. There are five of them. One is black, and has a red leather collar with a little silver bell; it belongs to the deaf old lady next door, and its name is Jetty. Another is yellow, and belongs to the lame girl in the white house with green blinds; its name is Topaz. The third cat is gray, with white front and paws. This is a lady cat, and her name is Malta; she belongs to the lady whom Johnny calls Mrs. Nose. Mamma does not allow him to say this, and he tries to remember, but sometimes he forgets; one day he said right out, “Good morning, Mrs. Nose!” and she only laughed, and said her nose was just the right size, and she needed it all to smell catnip with. She is a funny lady, and Johnny likes her, and Malta too.

The fourth cat belongs to Mr. Chops the butcher, and is a big tabby, with green eyes and fierce[3] whiskers. Johnny does not like him at all. But the fifth cat is Muffet, his own dear white kitten.

Now all these cats were friends except Bobs, the butcher’s cat. He lives on meat, and Mamma says perhaps that makes him cross. Anyhow, he is cross, and he growls and snarls and spits at Muffet and Jetty and Topaz and Malta, and tries to steal their fishbones, and upsets their milk, and is really a very horrid cat.

The story happened one night last week. Johnny was asleep, and Maggie was tidying up the nursery before going to bed, when suddenly she heard a queer noise. It came from the yard, and she stepped to the window and looked out. It was bright moonlight; and what do you think? The cats were having a party in the sand box! the four friendly cats, that is, Muffet and Topaz and Malta and Jetty. Maggie thought Muffet must have invited the others, for she was sitting in the middle of the box with her front paws tucked under her, looking so pleased and happy;[4] and the three others had their paws tucked in too, and they were all four talking in little soft mews, and seemed to be having a very good time. Then all of a sudden there was a snarl and a yowl, and that horrid great Bobs sprang over the fence and into the sand box, and began clawing and spitting and scratching right and left, just as hard as he could. At first the four friendly cats were too startled to do anything; but in another minute they began to spit and scratch and claw, and there were all five of them rolling over and over, scattering the sand on every side, and making such a noise that[5] it woke Johnny out of his sound sleep. At first he was frightened, but Maggie told him what it was, and said wait and see what she would do. She pushed up the fly screen very softly, and then she brought the great big jug full of water, and leaning out,—splash! she emptied it full on the fighting, struggling cats. Oh! how they yelled! One jumped this way, and one jumped that; and the next moment not one was left except poor little Muffet, sitting in the middle of the box and crying pitifully. “Oh, poor Muffy!” said Johnny. “Poor Muffy all wet!” So then good Maggie ran down and brought Muffet up, and dried her with a towel, and comforted her till she purred. Johnny wanted to take her into bed with him, but Maggie said that never would do; so,—what do you think? She put her in the doll’s cradle with Susan Dolly, and covered her up, and told her to go to sleep, and she did!

“Wake up!” said a clear little voice. Tommy woke, and sat up in bed. At the foot of the bed stood a boy about his own age, all dressed in white, like fresh snow. He had very bright eyes, and he looked straight at Tommy.

“Who are you?” asked Tommy.

“I am the New Year!” said the boy. “This is my day, and I have brought you your leaves.”

“What leaves?” asked Tommy.

“The new ones, to be sure!” said the New Year. “I hear bad accounts of you from my Daddy—”

“Who is your Daddy?” asked Tommy.

“The Old Year, of course!” said the boy. “He said you asked too many questions and I see he was right. He says you are greedy, too, and that you sometimes pinch your little sister, and that[11] one day you threw your reader into the fire. Now, all this must stop.”

“Oh, must it?” said Tommy. He felt frightened, and did not know just what to say.

The boy nodded. “If it does not stop,” he said, “you will grow worse and worse every year, till you grow up into a Horrid Man. Do you want to be a Horrid Man?”

“N-no!” said Tommy.

“Then you must stop being a horrid boy!” said the New Year. “Take your leaves!” and he held out a packet of what looked like copy-book leaves, all sparkling white, like his own clothes.

“Turn over one of these every day,” he said, “and soon you will be a good boy instead of a horrid one.”

Tommy took the leaves and looked at them. On each leaf a few words were written. On one it said, “Help your mother!” On another, “Don’t pull the cat’s tail!” On another, “Don’t eat so[12] much!” And on still another, “Don’t fight Billy Jenkins!”

“Oh!” cried Tommy. “I have to fight Billy Jenkins! He said—”

“Good-by!” said the New Year. “I shall come again when I am old to see whether you have been a good boy or a horrid one. Remember,

He turned away and opened the window. A cold wind blew in and swept the leaves out of Tommy’s hand. “Stop! stop!” he cried.[13] “Tell me—” But the New Year was gone, and Tommy, staring after him, saw only his mother coming into the room. “Dear child!” she said. “Why, the wind is blowing everything about.”

“My leaves! My leaves!” cried Tommy; and jumping out of bed he looked all over the room, but he could not find one.

“Never mind,” said Tommy. “I can turn them just the same, and I mean to. I will not grow into a Horrid Man.” And he didn’t.

“Why are you crying, Little Cat?” asked Little Dog.

“Because my paws are so cold!” said Little Cat. “I have been digging in the snow and I cannot find one.”

“One what?” asked Little Dog.

“One new leaf.”

“What do you want of a new leaf?”

“I want to turn it over, but there just aren’t any to turn.”

“Of course there aren’t!” said Little Dog. “It is winter.”

“But Little Girl is going to find one,” said Little Cat. “I heard her mother say to her, ‘You really must turn over a new leaf!’ and she said, ‘I truthfully will, Mamma!’ and when Little Girl says she truthfully will she always does. Then her mother kissed her, and said everybody had to turn over new leaves now, and she had some of her own to turn, so she knew just how it was. The door shut then—on the tip of my tail, too—and I heard no more; but what do you suppose it means?”

Little Dog shook his head. “We must ask somebody,” he said. “Let me see! Great Old Dog is out for a walk, and Crosspatch Parrot bit me the last time I asked her a question.”

“I know,” said Little Cat. “We will ask Old Cat in the Barn. She knows a good many things, and if she isn’t catching rats—but she generally is—she will tell us.”

They found Old Cat in the Barn sitting on a truss of hay, washing herself. She listened to Little Cat’s story, and her green eyes twinkled.

“So you have been looking for new leaves under the snow!” she said.

“Yes,” said Little Cat. “First I looked on the trees, and there weren’t any there; so I thought it must be leaves of plants and things, so I scratched and dug till my poor paws were almost quite frozen, but not one single scrap of a leaf could I find.”

“Fffff!” said Old Cat in the Barn. “This barn is full of ’em!”

“Full of leaves!” cried Little Cat and Little Dog together. “What can you mean, Old Cat? We don’t call hay leaves!”

“How many rats have you caught this week?” asked Old Cat, turning to Little Dog.

“None!” said Little Dog. “The last rat I caught bit me horridly; besides, they are odious,[23] vulgar beasts, and I don’t care to have anything to do with them.”

“Fffff!” said Old Cat. “Little Cat, how many mice have you caught in the kitchen this week?”

Little Cat hung her head. “I haven’t caught any,” she said. “I don’t care for mice, the flavor is too strong; I like cream better.”

“Ffffff! grrrr-yow!” said Old Cat; her green eyes shot out sparks, and her fur began to stand up. “Now, you two, listen to me! Why do you think the Big People keep you? Because you are soft and pretty and foolish? Not at all! They keep you because you are supposed to be useful. Your mother, Little Cat, was a hard-working, self-respecting mouser, who caught her daily mouse as regularly as she ate her daily bread and milk. Your father, Little Dog, hunted rats with me in this barn as long as he had legs to stand upon, and between us we kept the place in tolerable order. Great Old Dog cannot be expected to hunt at his age, and besides, he is too big; one might as well[24] hunt with an ox. But since your parents died you two lazy children have done next to nothing, and what is the consequence? I am worked to skin and bone, and the mice are all over the house; I heard Cook say so. Mind what I say; no creature, with four legs or two, is worth his salt unless he earns it, in one way or another. Now, what have you to say for yourselves?”

“Miaouw!” said Little Cat. “I am very sorry, Old Cat.”

“Yap! Yap!” said Little Dog. “I am sorry too, Old Cat.”

“Very well!” said Old Cat in the Barn. “Then turn over a new leaf!”

“Miaouw!” “Yap!” “That is just what we want to do!” said Little Cat and Little Dog together; “but we can’t find any.”

“The fact is,” said Old Cat in the Barn, “it is one of the foolish ways of speaking that the Big People have. It just means, stop being bad and begin to be good. Now do you see?”

“Prrr!” said Little Cat; “now I see. I will go and catch a mouse this minute, Old Cat.”

“Wuff!” said Little Dog; “I see, too, and I will come and hunt rats with you, Old Cat.”

“Prrrrrrr!” said Old Cat in the Barn. “That is right! Go to work, like good children, and as I may have been rather short with you lately I will turn over a new leaf, too, and ask you both to supper with me in my hay-parlor. Cook gave me the bones of the Christmas goose, and we will have a great feast.”

“Do I look nice?” asked the Rabbit.

“Very nice!” said the Chipmunk; “that is, for a person who has no tail to speak of. But, of course, you cannot help that.”

The Rabbit looked into the looking-glass pond and saw his little white blob of a tail. “Don’t you want to lend me yours, just this once?” he asked. “I would take great care of it!”

“No, I cannot do that,” said the Chipmunk, “but I can lend you the tail of my late uncle. It is such a fine one that we have kept it to brush out the nest with.”

“The very thing!” said the Rabbit.

So the Chipmunk brought the tail of his late uncle and tied it on to the Rabbit’s stub.

“How does that look?” asked the Rabbit.

“Fine!” said the Chipmunk. “Now tell me how I look!”

“Well enough!” said the Rabbit. “Of course, you would look better if you had long ears.”

“Dear me!” said the Chipmunk; and he, too, looked into the looking-glass pond. “Haven’t you a spare pair that you could lend me?”

“Why, yes,” said the Rabbit. “There is a pair that belonged to my grandfather, hanging on the wall at home. I will get those.”

So the Rabbit got the ears and tied them on to the Chipmunk’s head.

“How do I look now?” asked the Chipmunk.

“Splendid!” said the Rabbit. “Now let us go[30] and make our New Year’s calls. Where shall we go first?”

“I wish to call on Miss Woodchuck!” said the Chipmunk.

“So do I,” said the Rabbit. “We will go there first.” And off they went.

They came to Miss Woodchuck’s door and knocked, and she opened the door. “Mercy!” she cried. “Who are you, and what do you want?”

“We are Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Chipmunk,” said the two friends, “and we have come to make you a New Year’s call.”

“More likely you have come to steal the nuts!” said the lady angrily. “I know Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Chipmunk well, and neither of you is either of them. Who ever heard of a long-tailed rabbit or a long-eared squirrel? Get along with you! You are frights, and probably thieves as well.” And she shut the door in their faces.

The two friends walked a little way in[31] silence; then they stopped and looked at each other.

“You said I looked fine!” said the Rabbit.

“I—I meant the tail!” said the Chipmunk. “It is a fine tail. But you said I looked splendid!”

“I was thinking of the ears!” said the Rabbit. “They are splendid ears.”

They walked on until they came once more to the looking-glass pond. They looked at themselves; then they looked at each other; then, all in a minute, off came the long ears and tail.

“There!” cried the Chipmunk. “Now we look as we were meant to look; and I am bound to say, Rabbit, that it is much more becoming to you.”

“So it is to you!” replied the Rabbit. “Now shall we call on Miss Woodchuck again?”

“Come on!” said the Chipmunk.

So they went to Miss Woodchuck’s house, and knocked once more at the door, and Miss Woodchuck opened it. “Oh!” she cried. “Mr. Chipmunk[32] and Mr. Rabbit, how do you do? I am so glad to see you. A happy New Year to you both!”

“The same to you, Ma’am!” said the Rabbit and the Chipmunk.

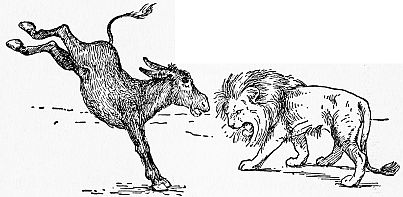

Once upon a time there was a donkey who lived in a field where there was no pond; so he had never seen his own image, and he thought he was the biggest and strongest and handsomest creature in the world.

One day a lion came through the field, and, being a polite beast, stopped to greet the donkey. “Good morning, friend!” he said. “What a fine day this is!”

“Fine enough, I dare say!” said the donkey. “I never think about the weather. I have other things to think about.”

“Indeed!” said the lion. “May I ask what things?”

“None of your business!” said the donkey[38] rudely; and he set up a loud braying, thinking to frighten the lion away.

“Why do you bray?” asked the lion.

“Bray!” cried the donkey. “That was not braying—it was roaring!”

“If you think I don’t know braying from roaring,” said the lion, still politely, “you are mistaken. That was a bray.”

“Very well!” shouted the donkey. “If that was, this shall not be!” and he uttered a long and loud “Hee-haw!” and kicked up his heels in angry pride. “What do you call that?” he asked proudly.

“I call it a bray,” replied the lion; “and a very ugly one. You see, after all, you are a donkey; look at the length of your ears!”

“How dare you?” cried the donkey. “My ears are the finest in the world, everybody says so. And as for roaring, if I have not scared you yet, just listen to me now!” And flinging up his heels again he bellowed till his own long ears tingled with the sound.

He expected the lion to be terrified, but the lion merely smiled.

“You certainly can make a most hideous noise,” he said; “but when all is said and done, it is only a bray. If you really wish to know how a roar sounds I shall be happy to oblige you.”

The King of Beasts then began to lash his tail and pretended to fall into a great passion. His eyes flashed fire, his tawny mane bristled; he opened his great mouth, and a roar like thunder filled the air. The donkey, after one terrified look, took to his heels and scampered off as fast as he could go, tumbled into a ditch, and lay there all day, not daring to move for fear.

The lion went on his way smiling. “It is a pity,” he said, “for a person to live in a place where he cannot see what he looks like.”

Tom had a cat who was so white that he named her Snow. He loved Snow and thought her the best cat in the world, but she would not come when she was called.

One day Snow went and played in the coal-bin, and when she came out she was quite black.

“See, Mother,” said Tom: “Snow cannot be Snow now, for she is black. What shall I name her?”

“You might name her Soot!” said his mother.

So he named Snow Soot. Snow did not care, and Soot did not care, but neither of them came when she was called.

One day Snow saw a tin pot on the shed floor, and Soot thought there might be cream in it; and Snow went to see, and Soot fell in, and it was[42] green paint, and when she came out she was all green.

“See, Mother,” said Tom. “My cat is not white now, so she cannot be Snow, and she is not black, so she cannot be Soot. What shall I name her now?”

“You might name her Grass,” said his mother, “till you have washed her; but I would wash her soon if I were you.”

So, Tom named the cat Grass. Snow did not care, and Soot did not care, and Grass did not care, but none of them came when they were called.

“How can I wash her,” asked Tom, “if she will not come when she is called?”

“Let me try!” said his mother. So she called, “Puss! Puss! Puss!” and the cat came running as fast as she could.

“Why-ee!” said Tom. “I think her name must be Puss.”

“I think so, too,” said his mother.

For every day, Johnny always wears blue; blue rompers in the morning, when he is playing in the sand box or helping Maggie make bread in the kitchen, and a blue sailor suit in the afternoon, when he goes “walk-a-walk-a” with Mamma. But on Sunday afternoon he goes walk-a-walk-a with Daddy (but they take Mamma too!), and then he has on his white sailor suit, and his white stockings and red shoes. Aunt Kitty brought him the shoes, and when they came there was a china cat inside one, and a tin frog inside the other. They were surprises, the cat and the frog; Aunt Kitty likes to give surprises.

Well! one Sunday morning Mamma and Daddy were going to church, and Maggie was very busy, so she put Johnny in the sand box, and told him[47] to play like a good boy, and he did. He made two forts, one with the red tin pail and one with the blue tin pail; and then he hammered on them with the old kitchen spoon and said, “Bang! bang! bang!” and that made a battle. While he was having the battle, the Boy Over the Fence came and looked through the pickets, and said, “Hurnh! I’ve got new shoes on!” Johnny looked, and he had; new brown shoes, that tied in front. So Johnny said: “I have new shoes too, only they are not on; they are up-stairs, and they are red.”

“They ain’t!” said the Boy Over the Fence. He was not a very nice boy.

“They are!” said Johnny. “Bright red, with wankle buttons. Aunt Kitty bringed them, and there was a cat in one, and a frog in the other, and they were s’prises. And white stockings too, so there!” Then he stopped, for he was out of breath.

“Hurnh!” said the Boy Over the Fence. “Let’s see ’em!”

Johnny trotted up the back stairs and brought down the white stockings and the red shoes; they were laid out on the chair, with the white suit, all ready for him to put on. He held them up so that the Boy Over the Fence could see them, and said, “So there!” again; it was all he could think of to say.

And the Boy Over the Fence said, “Hurnh!” again, as if that was all he could think of to say.

Just then Maggie opened the kitchen door and said: “Come in this minute of time, Johnny boy, and get your luncheon! see the nice cracker and the lovely mug of milk Maggie has for ye!”

Johnny was hungry, and he dropped the red shoes and white stockings and ran in to have his luncheon. While he was eating it, Maggie told him the story of the Little Rid Hin; (Mamma says it is “Red Hen,” really, but Maggie always says it the other way, and Johnny likes it better); and then she said it was time for his nap, and she whisked him up-stairs and tucked him up in his crib and told him to go to sleep like a good boy, and he went.

By and by he woke up, and Mamma came in to dress him for dinner. She washed his face and hands, and brushed his hair, and put on his white sailor suit; and then she said, “Why, where ever are the shoes and stockings?”

She looked under the chair, and on the bureau, and under the bed. “Johnny,” she said, “I cannot find your red shoes and white stockings. I put them here with your suit, and now they are gone.”

“Oh!” said Johnny.

“Do you know where they are, dear?” asked Mamma.

“Oh!” said Johnny again. “I think—they are in—the sand box!”

“In the sand box!” said Mamma.

“The Boy Over the Fence said they wasn’t red,” said Johnny; “and they was, and I gotted them and showed him, and then Maggie called me, and—and—I think that is all I know.”

“My goodness!” said Mamma. And she ran down-stairs and out into the yard to the sand box. But no red shoes or white stockings were there. Mamma looked all about carefully. There was the red tin pail, and the blue tin pail, both turned upside down, and the old kitchen spoon laid across them. And there were the marks of Johnny’s moccasins, and—oh! there were the marks of another pair of shoes, a little bigger than Johnny’s, with heels to them.

“My goodness!” said Mamma. “You don’t[51] suppose—” but she did not say what you didn’t suppose.

She looked over toward the next yard. There was no one there, but there were muddy footmarks leading from the fence to the sand box, and sandy footmarks leading back from the sand box to the fence.

“Now,” said Mamma, “I am afraid—” but she did not say what she was afraid of.

Just as she was stepping out of the sand box, her foot struck against the red tin pail and knocked it over; and—what do you think? Inside of the pail was one red shoe and one white stocking.

“My goodness!” said Mamma again. Then she turned over the blue tin pail, and there was the other red shoe and the other white stocking.

Mamma looked very severely over the fence, but no one was there; so she took the shoes and stockings up-stairs and showed them to Johnny. “Oh!” said Johnny.

She told him where she had found them; and then she put them away in the drawer, and brought out Johnny’s old brown moccasins and a pair of rather old brown stockings. “You shall wear these to-day!” said Mamma.

“But why?” said Johnny. “I like my red shoes and white stockings best.”

“But you took them out and left them in the sand box!” said Mamma.

“But I did forget!” said Johnny.

“But this will help you to remember!” said Mamma.

And it did.

Close beside the Pool of the Blue Lotus lived the two geese White-Wings and Gray-Back, and in the pool lived the tortoise Shelly-Neck, and the three were good friends. One night Shelly-Neck heard two fishermen talking together beside the pool. “To-morrow morning,” they said, “we will lay our nets and catch that old tortoise and cook him for our dinner.”

Shelly-Neck was much frightened, and when the men were gone he called his friends the geese, and begged them to save him.

“We will save you,” said White-Wings.

“But you must do just what we tell you to do!” said Gray-Back.

“I will! I will!” cried poor Shelly-Neck.

The two geese waddled about, looking till they[54] found a stick. “Now,” said White-Wings, “take this in your mouth and hold on tight!”

“And remember,” said Gray-Back, “that once you have taken hold you must not let go till we bid you.”

The tortoise promised and took hold on the middle of the stick with his strong jaws. Then White-Wings took one end of the stick in his bill and Gray-Back took the other, and they flew high up in the air over the roofs of the houses.

All the people came running to see this strange sight. “Look! look!” cried one. “See the flying tortoise!”

“Ho!” said another, who was one of the fishermen.[55] “He has no wings; soon he will forget and open his mouth, and then down he will come and we shall have him for dinner.”

“I will not let go! You shall not have me for dinner!” cried Shelly-Neck.

Crash! Down he fell on the hard ground. When the fishermen picked him up he was dead and they did have him for dinner.

White-Wings and Gray-Back flew sadly away. “We did our best,” they said; “but a fool cannot be saved from his folly.”

Great Old Dog was taking a nap before the parlor fire. He lay stretched out on the white bear skin, and reached almost from end to end, for he was a very great old dog indeed. By-and-by he woke up, and saw Little Dog sitting in front of him looking very melancholy.

“What’s the matter, young one?” asked Great Old Dog. “Where’s Little Cat?”

“I don’t know!” said Little Dog dolefully. “We don’t speak to each other any more.”

“Wuff!” said Great Old Dog. “Since when?”

“Since half an hour.”

“Wuff!” said Great Old Dog. “Why?”

“She was horrid to me,” said Little Dog, “about a bone; and—and then I was horrid to her.”

“And you think two wrongs make a right?” said Great Old Dog. “They don’t. That is monkey arithmetic, not fit for respectable dogs and cats. My advice to you is to make it up as soon as you can.”

“But she says she will never speak to me again!” said Little Dog piteously.

Great Old Dog yawned so wide that Little Dog could have got inside his mouth and turned around.

“She will!” he said.

“How do you know, Great Old Dog?”

“Wuff! I know cats.”

“I think she has gone out to see Old Cat in the Barn,” Little Dog continued. “Perhaps she may live out there and never come back.”

“She’ll come back,” said Great Old Dog. “She will miss you just as much as you miss her. Make it up, I tell you! Quarrelling is the silliest thing there is,” and he went to sleep again.

“Oh, dear!” said Little Dog. “I do miss Little Cat dreadfully, and the door is shut. Oh, oh dear!”

Little Girl was sitting at the desk, doing things with gold and silver paper. Little Dog went up to her and asked very prettily to be let out; but Little Girl was not so clever as usual.

“What is the matter, Little Dog?” she asked. “Do you want a valentine?”

“Please let me out!” said Little Dog; but she thought he said “Yap!”

“Listen, Little Dog!” she said. “Will this do?” She took up a frilled sheet with gold hearts on it and read:

“Please let me out!” said Little Dog; but she thought he said “Yap!”

“This is Valentine’s Day, Little Dog,” Little Girl went on. “You ought to send a valentine to Little Cat.

Why, Little Dog, you shall be her valentine. Come here, sir!”

Little Girl took a sheet of lace paper, crimped it into a frill, and tucked it into Little Dog’s collar. It tickled him woefully, but he said not a word, for he loved Little Girl almost next to Little Cat.

“You are lovely, Little Dog!” said Little Girl. “You are the best valentine I have made yet. Wait now!” She made a big star of gold paper and pinned it to his collar; then she made two little stars and pasted them on the tips of his ears.

“You are a lovely valentine!” she cried, clapping her hands. “And there is Little Cat mewing to be let in this minute. Now when I open the door, Little Dog, go straight up to her and say:

She opened the door and Little Cat started to come in, but when she saw Little Dog she stopped and looked shy.

Little Dog went up to her and said:

“If your heart is true as mine, Little Cat, I am sorry I was horrid about the bone; let me be your valentine and I want to make up.”

“Oh! Little Dog,” said Little Cat, “I was horrid first, and I was just coming to say I was sorry. Let’s never quarrel again, Little Dog; it is so lonely!”

“Dear little things!” said Little Girl. “They[64] are rubbing noses and telling each other something. Oh, dear! and I was cross to Brother this morning; I’m going to find him this minute and say I am sorry and ask him to be my valentine.”

One day Johnny followed Mamma up into the attic, where there are all kinds of pleasant things, and he saw a very pleasant thing indeed. It was a small dish, white with pink roses all over it; really and truly, it was the prettiest dish that ever was. Johnny said, “O-o-oh! may I have that dish for mine?”

Mamma looked, and then she took the dish in her hand and thought a minute. Mamma always likes to be sure about things before she says “Yes!” for fear it might not really be “yes” after all. But now she nodded her head, and said, “Yes, Johnny, you may have it.”

“O-oh!” said Johnny. “For my welly own?”

“For your very own. The rest of the set is broken, and I have just kept this dish because it[71] is so pretty. Now you may take it down into the nursery, and have it for a bath for Flora.”

Flora was a small doll, all china, and her clothes came off, so she could have a bath any time, and Johnny often gave her one. Now he gave her one in the rosy-posy dish, and it was just exactly the right size, and Johnny was so pleased, and said, “Oh, thank you, dear Mamma!” without having to be told. (Sometimes he forgets to say “thank you,” but he is getting to be quite good about it.)

The next time Johnny went down-stairs, he took the doll’s bath to show to Maggie, and she said ’twas the pick of the world for a dish, and asked Johnny to lave her bake a cake in it; but Johnny said no, not now, though perhaps by and by, for now he must take it out to show to Muffy. Muffet was out in the sand-box, and when Johnny showed her the dish she mewed and rubbed against his legs, and seemed to want something very much.

“Maggie,” said Johnny, “Muffy wants something! What do you suppose it is?”

“Sure she might be wanting a sup o’ milk!” said Maggie. “Bring me here the grand dish and we’ll give the crature a sup in itself, and won’t she be the proud kitty!” that is the way Maggie talks; it is a nice, funny way, Johnny thinks.

Well! so Maggie filled the pretty dish with milk, and Johnny set it down in the sand box before Muffet, and she lapped it up, every single drop, purring all the time. Johnny was watching her when Mamma called him in to take his nap. Muffet had not quite finished, so he left the dish standing, and ran in to Mamma, and then he went for his nap. When he woke up it was raining hard, and it rained all the afternoon, so he did not go out again, but stayed in the nursery building a Choo Choo House. The next morning was bright and clear, and the very first thing Johnny thought of, when he had had his bath, and Mamma was dressing him, was the rosy posy dish.

“I wants my diss,” said Johnny, “to give Flora her bath!”

So Mamma looked for the dish, all over the nursery, but it was not to be found.

“Where did you leave it, Johnny Boy?” said Mamma. “Think a minute!”

So Johnny thought a minute, and then he remembered. “I left it in the sand box,” he said. “Muffy was very thirsty, and she was drinking out of it, and you called me, and she hadn’t finished, and so, you see—and so, you see—”

And Mamma said she saw. Then she looked out of the window, and said yes, there was the dish, right in the sand box, beside the red tin pail and the blue tin pail and the old kitchen spoon. Then she said, “Oh! oh, Johnny, come here and look!”

So Johnny went to the window, and stood on his tippy-toe-toes, and looked; and what do you think he saw? A little brown sparrow had come fluttering down, and was drinking out of the rosy posy dish. (You see, it had rained all night, so the dish was full of water.) He perched on the edge, and dipped his little beak in, and drank and[74] drank; he must have been very thirsty. And then—oh! oh! what did he do but hop down into the dish, and begin taking his bath! He splashed, and he shook himself, and rustled his feathers, and then he splashed again. “Oh!” said Johnny. “Oh! Mamma, he is doing it all himself. Nobody told him to, not one bit.”

“No, indeed!” said Mamma. “He likes to take his bath and be clean, just as Johnny does. He knows it feels good to be clean.”

“Mamma!” said Johnny. “I want to tell you something. Shall we have something else for[75] Flora, and let the rosy posy dish be the sparrow’s bath, his ownty donty?”

“Suppose we do!” said Mamma. And they did.

Mr. Peacock was proud. He had a fine long train, a splendid crest, and the gayest blue-green coat that ever was seen; and all day long he would strut up and down the barnyard and say: “See what a beauty I am!”

The geese and ducks and turkeys were much displeased at this. “Beauty, indeed!” they said. “Of what use is your beauty? Can it hatch eggs?[79] Tell us that!” and they turned their backs and walked away.

“These are stupid creatures!” said Mr. Peacock. “Why should I stay among them? I will go to the Fair, for there people will see my beauty and admire it.”

So he spread his tail like a fan, raised his crested head and strutted off down the road to the Fair. Pretty soon he met some young men who also were going to the Fair. “Aha!” said Mr. Peacock. “These people will admire me!” and he strutted more than ever.

“Look!” said the young men. “What a fine peacock, and what splendid feathers he has! They are just what we want for our hats.” They surrounded Mr. Peacock, and, spite of his screams of rage and terror, tore out three or four of his finest tail feathers and went away laughing. Presently he fell in with a large flock of geese which a boy was driving to the Fair to sell. He spread his tail and tried to push his way to the[80] head of the flock, but they took no notice of him and waddled steadily on, keeping close together.

“Make way, you stupid creatures!” said Mr. Peacock. “Keep your dirty feet off my fine train!”

“Quack!” said an old gray goose, the grandmother of the flock. “Keep your train out from under our feet, Mr. Strut! Who asked you to join our company?”

“Join your company, indeed!” cried Mr. Peacock. “Get out of my way, you rude, clumsy thing, and learn how to treat your betters!” and he gave the goose a hard peck.

When the other geese, who loved their grandmother, saw this, they all fell upon Mr. Peacock and beat and pecked and hustled him till he ran screaming away, dragging his tail behind him.

He was now in a sad way, covered with dust, and many of his finest feathers were torn and broken; but still, when he came to the Fair he[81] spread his tail, reared his crest and made as much of himself as he could.

“I am still handsomer than any one else!” he said, “and people will be sure to admire me.”

“Look there!” said a man. “There is a peacock. Let us kill and stuff him and add him to our show.” And he chased Mr. Peacock, who ran off screaming with terror. Coming around a corner he ran into a large dog who was coming the other way.

“Get out of my way!” screamed Mr. Peacock.

“Get out of mine!” growled Mr. Dog, and he grabbed Mr. Peacock by the neck, shook him hard and tore out a great mouthful of feathers.

More dead than alive, the poor Peacock ran and ran and ran, and never stopped till he got home.

The geese and turkeys looked at him in great surprise. “Who is this wretched, shabby bird?” they asked each other. “It cannot possibly be Mr. Peacock?”

“Yes,” sobbed the poor creature, “it is I; but I have left my pride behind. If you will only let me stay with you I will do my best to hatch eggs.”

But he never could.

“Where are you going in such haste, friend?” said Trusty, the shepherd’s Dog, to a great wolf that was jogging along the same road.

“If I were sure you would not betray my secret,” said the Wolf, with a sly leer, “I would let you know.”

“You need not fear me; I shall tell no one a word of the matter,” said Trusty.

“Well, then,” said the Wolf, “you must know, as I was prowling around yonder cottage I saw the farmer’s wife put a fine baby into the cradle, and heard her say: ‘Lie still, my darling, and go to sleep, while I run down to the village to buy bread for your father’s supper.’ As soon as the babe is asleep I shall go and fetch it: it is fair[86] and fat, and will make a nice supper for me and my cubs.”

“Then,” said Trusty, “I would advise you to wait a little longer, for I saw the baby’s mother step into the next house to speak to a neighbor: take care lest you are seen.”

The Wolf thanked the Dog for his good advice, for he did not know that the baby belonged to Trusty’s master; and he said he would take heed and keep close.

Then Trusty ran home with all the speed he could. The door was ajar, and the innocent baby was fast asleep in the cradle; so he lay down on[87] the mat behind the door and listened for the coming of the Wolf. It was not long before he heard the tread of the Wolf’s feet on the gravel path, and in another minute the savage beast was in the room and stealing with cautious steps to the cradle; but just as he was preparing to seize the poor baby Trusty sprang upon him and after a fierce struggle laid him dead on the floor.

The first thing the mother saw on her return was the Wolf dead at the foot of the cradle, while the baby, unhurt, lay soundly sleeping on his little pillow, and faithful Trusty watching beside him. She flew to look the little one all over, to make sure that he was safe and sound, and then, oh! how she patted and fondled the good Dog who had saved her darling’s life! She called in all the neighbors, and told them what Trusty had done, and from that time he became the pet of the whole village, and all the mothers wished they had such a dog to watch over their children.

Once a poor Crane was caught in a net, and could not get out. She fluttered and flapped her wings, but it was of no use, she was held fast.

“Oh!” she cried, “what will become of me if I cannot break this net? The hunter will come and kill me, or else I shall die of hunger, and if I die who will care for my poor little young ones in the nest? They must perish also if I do not come back to feed them.”

Now Trusty (the same Trusty who saved the baby’s life) was in the next field and heard the poor Crane’s cries. He jumped over the fence, and seizing the net in his teeth quickly tore it in pieces. “There!” he said. “Now fly back to your young ones, ma’am, and good luck to you all!”

The Crane thanked him a thousand times. “I wish all dogs were like you!” she said. “And I wish I could do something to help you, as you have helped me.”

“Who knows?” said Trusty. “Some day I may need help in my turn, and then you may remember me. My old mother used to say to me:

Then Trusty went back to mind his master’s sheep, and Mrs. Crane flew to her nest and fed and tended her crane babies.

Some time after this she was flying homeward and stopped at a clear pool to drink. As she did so she heard a sad, moaning sound, and looking about, whom should she see but good Trusty, lying on the ground, almost at the point of death. She flew to him. “Oh, my good, kind friend,” she cried, “what has happened to you?”

“A bone has stuck in my throat,” said the Dog, “and I am choking to death.”

“Now, thank Heaven for my long bill!” said Mrs. Crane. “Open your mouth, good friend, and let me see what I can do.”

Trusty opened his mouth wide; the Crane darted in her long, slender bill, and with a few good tugs loosened the bone and finally got it out.

“Oh! you kind, friendly bird!” cried the Dog, as he sprang to his feet and capered joyfully about. “How shall I ever reward you for saving my life?”

“Did you not save mine first?” said Mrs. Crane. “Shake paws and claws, friend Trusty![91] I have only learned your mother’s lesson, which you taught me, that

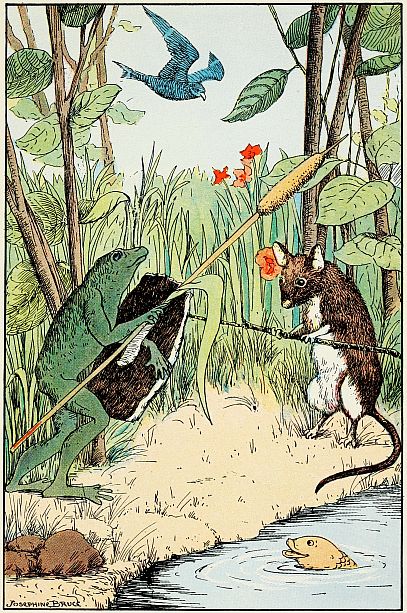

“I will be King of the Fen!” said Croaker the Frog, leaping out of the brook upon the dry land.

“You King, indeed!” said Slyboots, a fine, fat Field Mouse with a long tail and bright eyes, jumping out of his hole at the foot of a hazel bush which grew near. “I am larger than you, and I will be King, and the frogs shall be my subjects and cut rushes and bring me dry moss to line my nest.” And Slyboots strutted about and gave himself a great many airs.

[93]“I will never consent to be ruled by a Mouse,” replied the Frog with a disdainful air. “How finely King Slyboots would sound!”

“Quite as well as King Croaker!” retorted the Mouse.

Then the Frog flew into a great passion and hopped so high and croaked so loud that the Mouse crept a little farther from him (for frogs, like children, look very ugly when they are out of temper); and Slyboots did not much like the idea of being touched by his cold paws, and he said to himself: “In spite of this Frog’s looking so fierce and talking so loud I should not wonder if he were a coward at heart.”

So he turned to the Frog and said: “As we both wish to be King of the Fen I know of no way of ending the dispute but by fighting, and the one that wins the fight shall be King over the other.”

Then the Frog said: “Very well! We will each bring a friend to see fair play. To-morrow at twelve o’clock I shall be ready to take the field;[94] and if you fail to meet me here I shall be King of the Fen, and the mice shall be my servants.” For Croaker thought Slyboots was braver in word than in deed, as cowards are often the foremost to talk of fighting.

Then the Frog retired among the bulrushes and the Mouse ran home to his hole under the nut tree.

The two rivals awoke next morning by break of day to prepare for the combat, which was to take place at noon. The Frog was very much afraid of Slyboots’s sharp teeth and claws, so he fell to work and made a shield from the bark of an old willow tree, and then he plucked a long bulrush for a spear. “Now,” said he, “I am well armed: I have a shield to defend myself and a spear to attack the enemy with. If I had but a brave friend to be my second in the fight I should do very well.”

“I will be your second,” said a great Pike, raising his head above the water; “I will lie close to the bank among these rushes, and if you break[95] your spear come to me and I will procure you another.”

The Frog was well pleased at this offer. “I shall beat Slyboots in a little time,” said he, “with such weapons and so good a friend.”

Slyboots in the meantime was not idle; he sharpened his teeth and his claws and chose a light twig from the hazel bush and said: “I only want now a friend to be my second and see fair play.” A great Hawk, which was hovering near, said: “Mr. Slyboots, you may command my services at any hour you please to name.”

Now Slyboots was somewhat afraid of the Hawk, for he thought he had rather a hungry look about the eyes and beak, but he dared not refuse his offer lest he should give offence; so he thanked him for his kindness, and at the appointed hour they went to the spot where the Frog was waiting for them. The Pike lay in the hole among the rushes and the Hawk sat on the bough of a tree close by.[96]

The Frog and the Mouse looked at one another for a few minutes and shook their weapons. At last the Hawk and the Pike gave signal for the fight to begin. The battle was long and fierce on both sides, and for some time it was doubtful which would win. At last the Frog seemed to gain ground, but at the very minute that he seemed to be winning his spear broke in pieces.

“Alas!” croaked he in a tone of dismay, “what shall I do? Who will give me another weapon?”

“Here is one,” cried his friend, the Pike, from among the rushes.

The Frog gave a leap of joy and sprang toward the Pike, who, opening his mouth, quickly put an end to the battle by swallowing the hapless Frog at one mouthful.

“I am King of the Fen now!” cried Slyboots with a joyful squeak. “Long live your Majesty!” exclaimed the crafty Hawk. As he spoke[97] he darted from the tree and, pouncing upon the new monarch, bore him away in his claws and put an end to his reign and his life at the same moment.

“Summer is gone!” said the Trees. “The fall of the year is come, and it is time for us to dress up and be gay.”

“I shall wear red!” said a Maple. “Sunset red is my color.”

“Yellow for me!” said another. “My dress shall be like pure gold.”

“I choose purple!” said the Ash. “It is the color of Kings, and suits me very well.”

“What will you wear?” they all said to the little Fir.

“I have no other dress!” said the Fir sadly. “I must wear my plain green frock.”

“Te hee!” laughed the Maples and Birches and Ash trees, rustling their leaves and nodding their heads. “She has but one dress! What a poor thing she is!”

But the old Pine waved his dark branches and said: “Hush! hush! I know what I know!”

“We know, too,” cried the Maples. “We know that in snow-time Santa Claus comes, and chooses the finest tree, and dresses it in gold and silver and hangs stars all over it. That is why we wish to be fine and gay.”

“Hush! hush!” said the old Pine. “I know what I know.”

So the trees put on their gay robes, gold and red and purple, and each one was finer than the rest; only the little Fir and the great old Pine stayed just as they were, in their plain green dresses.

Now it grew cold, and a bleak wind blew through the forest. The trees shivered and drew their bright robes close around them. Colder still it grew, and snow fell, and the wind moaned; one day Jack Frost came in his silver coat and touched the bright leaves with his shining brush, and they curled up and turned brown, and,[102] one by one, fell rustling to the ground. Soon the poor Maples and Birches and the purple Ash who thought he looked like a King stood all bare, and the wind blew through their branches, and they shook with the cold. They looked at the Fir and wished that they had her warm, green dress. Now came Santa Claus, driving his reindeer team through the forest, cracking his whip and jingling his bells. He looked at the trees with his bright eyes.

“Ho! ho!” he said as he saw the Maples and Birches. “What a beggarly set! Why, they have[103] not a cloak among them to keep them warm. These will never do for me.”

But now he saw the little Fir, and a smile came over his face.

“This is the tree for me!” he cried. “Will you come with me, little Fir, and be the children’s tree, and make many hearts glad?”

“That I will!” said the little Fir gladly.

So Santa Claus took her away and dressed her in gold and silver and hung bright stars all over her; and she became the Christmas Tree, and many hearts were glad because of her.

“Hush! hush!” said the old Pine. “I knew what I knew.”

Once upon a time in a deep wood lived a Deer and a Crow, who were great friends and loved each other dearly. One day, as the Deer was roaming about alone, he met Small-Wit, the Jackal.

Small-Wit was hungry, and when he saw the fine fat Deer he said to himself: “Oho! if only I could have this fat Deer for my supper!” So he went up to the Deer, hanging his head and looking very sad.

“Who are you, Friend?” asked the Deer, “and why do you look so sad?”

“My name is Small-Wit,” said the Jackal; “and I am sad because I have not a friend in the world. Ah! if I could win your friendship how happy I should be!”

“Very well,” said the Deer, who was very[110] good-natured. “Come with me, and we will be friends.”

He led the way to his home, and the Jackal followed him. As they drew near, Sharp-Sense, the Crow, called from the tree where he was perching: “Who is this number two, Friend Deer?”

“It is Small-Wit, the Jackal,” said the Deer. “He is lonely, and wishes to be our friend.”

said the Crow.

“Nay!” said the Deer. “I like this rhyme better:

“Very good,” said Sharp-Sense: “as you will.”

Next morning they went off hunting, and the Jackal said to the Deer: “I know a field of sweet corn, and I will take you there.”

So the Deer followed Small-Wit, and, sure enough, they came to a field of sweet young corn.

“You are a friend indeed!” cried the Deer, and he feasted till suddenly he fell into a snare which the farmer had laid.

“Alas!” cried the Deer, “Friend Small-Wit, here am I caught by the feet, and cannot move. Come, I pray you, and gnaw these cords with your sharp teeth and set me free!”

The Jackal came and looked at the snare. “That will hold you fast enough,” he said. “To-day is a fast day, but to-morrow I will have a fine feast on your fat carcass, my foolish friend.” And off he went.

Presently came along Sharp-Sense, the Crow, who had been looking for his friend. “Alas!” he cried, “how did this happen, Friend Deer?”

“Through not minding what you said,” replied the Deer.

“Well,” said the Crow, “we must do what we can. Here comes the farmer. Do you lie still and pretend to be dead until I croak: then spring up and be off.”

The farmer came along and saw our friend lying perfectly still. “Aha!” he cried, “this fellow will eat no more of my corn.”

He stooped down and untied the cords of the snare, meaning to carry off the dead Deer; but at that moment the Crow gave a loud “Caw!” Up sprang the Deer and in a moment was safe in the[113] forest. The farmer flung a club after him; it hit Small-Wit, the Jackal, who was lurking near by hoping to have a share of the spoil, and killed him; and the two friends went home happy.

In a southern garden lived a family of green lizards, under the roots of a palm-tree. They were merry little creatures, and their parents loved them dearly.

One day Father Lizard said to his children: “Your mother and I must go away this morning; now be good children; stay close together, and be sure that one of you keeps watch for fear of snakes and hawks!”

The little lizards promised; and for some time they were very careful; first one kept watch, and then another; but at length Sprightly said: “There is no danger near. Why should we not all play together, just for a little while?”

Oh dear! they forgot their promise, and see what came of it! While they were playing merrily,[115] a great snake glided quietly out from the grass, seized poor Sprightly, and carried her off to his den.

The other lizards fled in terror. Swiftfoot ran up the tree, Longtail hid in the nest, and Goldstar ran away and away, to the farthest end of the garden. She did not dare to go home again, but found a hole in the bank near a summerhouse, and slipping into it, stayed all night, weeping for the death of her dear Sprightly.

Next day she tried to find her way home, but the garden was large, and she was too afraid of snakes to go far; so she decided to stay where she was, and make her home in the hole by the summerhouse.

One day, as she was lying in the sun, Goldstar saw a boy standing near her, with a cane in his hand. At first she was afraid to move, fearing he might strike her; but Carlos (for that was the boy’s name) was fond of lizards, and would not have hurt one for the world. He spoke softly to[116] Goldstar, and she soon saw that he was kind and good. He stroked her gently, first with a green leaf, then with his hand, and Goldstar lay still, and was not afraid any more.

They became great friends, and Carlos came every day to see his pretty lizard and play with her. One day, as he was coming down the garden walk, he saw a large hawk hovering in the air near the summerhouse, just about to dart down on something. “Oh! my lizard! my lizard!” cried Carlos; and he ran as fast as he could to the spot, shouting and waving his arms. The hawk flew screaming away, and Goldstar ran to Carlos, and crept inside his jacket. She could not speak, but he knew that she was glad, and perhaps was trying to thank him in her own way.

One very hot day, Carlos was taking a nap in the summerhouse, when he was waked by something running over his face. He brushed it away without opening his eyes, but it came again, and[117] still again. In fact, he could not get rid of it. At last he sat up, wide awake and very angry, and found that it was Goldstar. He tried to shake her off, but she ran into his bosom. He was going to pull her out in a pet, when, looking down, he saw a large snake, with head raised and glittering eyes, gliding slowly toward him. He knew its bite was fatal, and he sprang up with a loud cry. The snake stopped, and then turning, glided away into the bushes.

Very gently, Carlos drew his little pet from his bosom, and stroked her green and golden back.[118] “Dear Goldstar,” he said, “if I saved you from the hawk, you have saved me from the serpent. I will love you and take care of you as long as you live.” And so he did.

A pair of crows had their nest in a certain tree. It was a fine tree, and suited them well, but they had a bad neighbor, a black snake, who often stole and ate their young ones.

“Husband,” said Mrs. Crow, “we must leave this pleasant home of ours; we shall never be able to rear our children while that bad snake is there.”

“My dear,” replied Mr. Crow, “think no more about him. I have had enough of Black Snake, and I am going to get rid of him.”

“What can you do against a huge snake like that?” asked Mrs. Crow.

“Listen!” said Mr. Crow. “As you know, the Prince comes every day to bathe in the fountain under our tree. He has a fine gold chain, and he[122] takes it off before he goes into the water, and lays it on a stone. To-morrow, when he does this, do you take the chain in your beak (for I shall be away getting food for the babies), and drop it into the hollow of the tree, taking care to give some good loud ‘Caws’ while you do so. Then wait and see what happens!”

Sure enough, next morning the young Prince came as usual to bathe in the clear fountain. He took off his gold chain and laid it on a stone, just as Mr. Crow said he would; then he began to take off his robes. Just then down flew Mrs. Crow, took the chain in her yellow bill, and flew up into the branches with it. “Oh! my chain! my chain!” cried the Prince. “That crow has flown away with it!”

“Have peace, your Highness!” replied his servant. “The bird has not flown far; she has this instant dropped the chain into a hole in the tree, and I will climb up and get it.”

Up climbed the servant, and looked down into the hole.

“Do you see my chain?” cried the Prince.

“Yes,” said the servant, “I see it, shining in the hole, but I see something else that is not so pretty; the head of a great ugly black snake. If your Highness will throw me up a stone, I will kill the creature, for it is a poisonous snake.”

So the Prince threw up a stone, and the servant[124] caught it, and killed the snake with it. Then he reached down into the hole, pulled out the gold chain, and took it back to his master, who thanked him kindly.

“Ah!” said Mrs. Crow. “He is glad to get back his fine jewel; but I am far happier, for I have my babies safe and sound. See what it is to have a clever husband! I must be sure to have everything he likes best for supper to-night.”

So she did! I do not know what crows like best for supper, so I cannot tell you; but they had a wonderful feast, and the little ones picked the bones, and there was no happier family in all the forest than the Crow Family.

There are many old, old stories about the dear Christ Child when he was little. Not all of them are true, but all are sweet and lovely; listen now, and you shall hear one.

It had been raining in Nazareth, and the ground, which had long been parched and dry, was turned to wet clay. This was a wonderful thing for the children, and they all ran to play with the clay, just as you boys and girls do now. Some dug canals and wells, some built houses and towers; while others took the soft clay in their hands and moulded it into shapes of men and animals.[136] The little Jesus joined this last group, and while they made dogs and cats, horses and lions, he made little gray doves, and set them one by one on the edge of the fountain.

Presently sweet Mary the Mother came to the door and looked out, to see what the children were doing.

“See!” cried one little boy. “Mary Mother, see my dog! he can almost wag his tail and bark.”

“Look at my lion!” cried another. “He is so big and strong, he could eat up your dog in a minute.”

“Ho!” said a third. “My man here could whip your dog, and kill your lion with his sword, so he is the best of all.”

Mary Mother smiled, and praised the dog, the lion, and the man. Then she said, “And what has my little Jesus to show me?”

“I have made some little gray doves,” said Jesus. “See! here they are!”

“And what can they do, my little one?” asked[137] sweet Mary, as she stroked the boy’s curly head.

“I think they can fly!” said little Jesus. “Fly, pretty doves!”

He clapped his hands, and up flew the doves like a soft gray cloud. Then fluttered round the child’s fair head, and lighted for a moment on his shoulders and his hands; then they spread their gray wings and flew up into the sky, and were seen no more.

“What is going on to-day, Little Cat?” asked Little Dog. “Every one seems so happy and merry. I had chicken-bones for breakfast, with ever so much meat on them!”

“I had creamed fish,” said Little Cat; “and it was real cream. Look! Little Girl tied a red ribbon round my neck, and said I was a beauty. Am I, Little Dog?”

“Yes, for a cat!” said Little Dog. “Am I?”

“Yes, for a dog!” said Little Cat.

“I have a new collar, you see,” said Little Dog. “And your girl has on a new blue dress, and my boy a velvet jacket. And they are not going to say one cross word all day; I heard them tell their mother so.”

“I was in the nursery this morning,” said Little[139] Cat. “The children’s stockings were full of toys and sugar-plums, and they kissed each other and said, ‘Merry’—something! What can it all mean?”

“Let us ask Great Old Dog!” said Little Dog. “He knows almost everything, and he can surely tell us.”

Great Old Dog was asleep, but he woke up and heard their story patiently. “It was ‘Merry[140] Christmas!’ that the children said,” he told them. “This is Christmas Day.”

“What does it mean?” asked Little Cat.

“I don’t understand all about it,” said Great Old Dog; “but it is the best day in the whole year, for everybody is happy and kind, and tries to do pleasant things for everybody else. I think some one was born who brought kindness into the world.”

“Well,” said Little Dog; “if everybody is going to be good we must be good, too. Little Cat, I will not growl at you once to-day, even if they put our dinner on the same plate!”

“Nor I at you,” said Little Cat, “even if there is only one cushion by the fireside.”

“Nice Little Cat!” said Little Dog.

“Good Little Dog!” said Little Cat.

Just then in came Little Girl in her blue dress and Little Boy in his velvet jacket. “Merry Christmas!” they cried: “Little Cat and Little Dog, and dear, good Great Old Dog!”

“Merry Christmas!” said Little Dog (but it sounded like “Yap! yap!”).

“Merry Christmas!” said Little Cat (but it sounded like “Purrrrrrrrrrr!”).

“Merry Christmas!” said Great Old Dog, deep down in his great old throat (but it sounded like “Wuff! Wuff! WUFF!”).

“Mother,” said Jack, “may I have some money to buy Christmas presents with?”

“Dear,” said his mother, “I have no money. We are very poor, and I can hardly buy food for us all.”

Jack hung his head; if he had not been ten the tears would have come to his eyes, but he was ten.

“All the other boys give presents!” he said.

“So shall you!” said his mother. “All presents are not bought with money. The best boy that ever lived was as poor as we are, and yet he was always giving.”

“Who was he?” asked Jack; “and what did he give?”

“This is his birthday,” said the mother. “He was the good Jesus. He was born in a stable, and[143] he lived in a poor workingman’s house. He never had a penny of his own, yet he gave twelve good gifts every day. Would you like to try his way?”

“Yes!” cried Jack.

So his mother told him this and that; and soon after Jack started out, dressed in his best suit, to give his presents.

First, he went to Aunt Jane’s house. She was old and lame and she did not like boys.

“What do you want?” she asked as she opened the door.

“Merry Christmas!” said Jack. “May I stay for an hour and help you?”

“Humph!” said Aunt Jane. “Want to keep you out of mischief, do they? Well! you may bring in some wood.”

“Shall I split some kindling, too?” asked Jack.

“If you know how!” said Aunt Jane. “I can’t have you cutting your foot and messing my clean shed all up.”

Jack found some fresh pine wood and a bright[144] hatchet, and he split up a great pile of kindling and thought it fun. He stacked it neatly, and then he brought in a pail of water and filled the kettle.

“What else can I do?” he asked. “There are twenty minutes more.”

“Humph!” said Aunt Jane. “You might feed the pig.”

Jack fed the pig, who thanked him in his own way.

“Ten minutes more!” he said. “What shall I do now?”

“Humph!” said Aunt Jane. “You may sit down and tell me why you came.”

“It is a Christmas present!” said Jack. “I am giving hours for presents. I had twelve, but[145] I gave one to Mother, and another one was gone before I knew I had it. This hour was your present.”

“Humph!” said Aunt Jane. She hobbled to the cupboard and took out a small round pie that smelt very good. “Here!” she said. “This is your present, and I thank you for mine. Come again, will you?”

“Indeed I will!” said Jack, “and thank you for the pie!”

Next Jack went and read for an hour to old Mr. Green, who was blind. He read a book about the sea, and they both liked it very much, so the hour went quickly. Then it was time to help Mother get dinner, and then time to eat it; that took two hours, and Aunt Jane’s pie was wonderful. Then Jack took the Smith baby for a ride in its carriage, as Mrs. Smith was ill, and they met its grandfather, who filled Jack’s pockets with candy and popcorn and invited him to a Christmas Tree that night.

Next Jack went to see Willy Brown, who had been ill for a long time and could not leave his bed. Willy was very glad to see him; they played a game, and then each told the other a story, and before Jack knew it the clock struck six.

“Oh!” cried Jack. “You have had two!”

“Two what?” asked Willy.

“Two hours!” said Jack; and he told Willy about the presents he was giving. “I am glad I gave you two,” he said, “and I would give you three, but I must go and help Mother.”

“Oh, dear!” said Willy. “I thank you very much, Jack. I have had a perfectly great time, and it has driven the pain away; but I have nothing to give you.”

Jack laughed. “Why, don’t you see,” he cried, “you have given me just the same thing? I have had a great time, too.”

“Mother,” said Jack as he was going to bed, “I have had a splendid Christmas, but I wish I[147] had had something to give you besides the hours.”

“My darling,” said his mother, “you have given me the best gift of all, yourself!”

Pussy White and Doggy Brown were in the yard one day. Doggy Brown thought he would like to go into the house, so he went to the door, but it was shut. He tried to open it by bumping against it, but in vain. Then he barked, but no one heard him. Then he felt very sad, and sat down by the door and howled.

Pussy White had been watching him with one eye, while she dozed with the other.[158]

“Dogs are not very clever!” she said. Presently she went to the door and jumped up and lifted the latch with her paw. The door swung open.

“There!” she said.

“Oh, Pussy!” said Doggy Brown. “Thank you; how clever you are!”

“That is one way of putting it,” said Pussy White; “but you are welcome, all the same.”

Now this is true, for we saw it with our eyes. Dick was a bachelor, or so we had always supposed: a large black bachelor, with bright green eyes, and a very fine tail. He lived in the kitchen, and managed things pretty much as he pleased. When Peter, the new puppy, came he thought it would be fun to tease Dick. Dick thought it would be fun to be teased, and when he had sent Peter yelping and ki-yi-ing out into the shed, he sat and purred and blinked his green eyes, and thought the world a pleasant place.

Now one day we looked out of the south parlor window, and what do you think we saw? Dick was coming across the lawn looking very proud and very happy. Every now and then he stopped and looked over his shoulder and mewed as if he were calling some one to follow him. And some[160] one was following him! Across the lawn after him came:

One very thin and wretched-looking tortoise-shell cat.

One Maltese kitten.

One yellow kitten.

All three looked half-starved, and all three were scared out of their wits!

“Come on!” said Dick, as plain as mew could speak. “They won’t hurt you; those are my people: they belong to me. Come on, I tell you!”

They came on, though still very timidly, till they reached the barn. Then Dick took them under the barn and there he made them comfortable, we do[161] not know just how, because we cannot get under the barn, and there they stayed. And when Dick came for his supper he said to Maggie as plain as mew could speak, “Please feed my family, too!” and Maggie did.

That was a year ago. Now the tortoise-shell cat is dead, but the Maltese kitten and the yellow kitten are large and handsome cats, and Dick still sits by the fire and purrs, and blinks his large green eyes.