Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. Contents: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

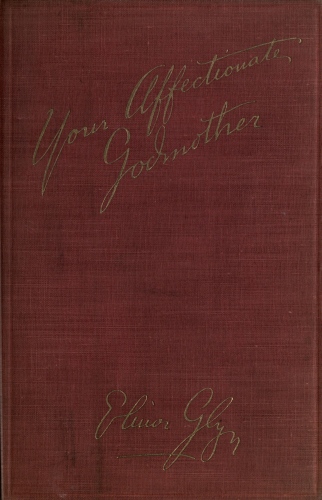

Your Affectionate

Godmother

| By ELINOR GLYN |

| Your Affectionate Godmother The Point of View Guinevere’s Lover Halcyone The Reason Why His Hour |

| D. APPLETON AND COMPANY New York and London |

By

Elinor Glyn

Author of “The Point of View,” “The Reason Why,” etc.

Illustrated by Grace Hart

D. Appleton and Company

New York 1914

Copyright, 1914, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

——

Copyright, 1912, 1913, by Harper’s Bazaar, Inc.

——

Published in England as

“Letters to Caroline”

November, 1912.

NOW that you are soon about to return from Paris, Caroline—polished, let us hope, in education—it may be interesting for us to have some little talks together upon the meaning of things and the aspects which life is likely to present to you.

If you had been with me from early childhood you would by now have grown so completely to understand my point of view that words would not be necessary between us. But circumstances have arranged that only in your eighteenth year have you been given into my charge, so, as I want you to be happy, my dear godchild, we must lose no time in looking at a number of points which can assist that end.

I understand, by what I know of your character, that you have a clear idea of what you want, and that is to take some place in the world of no mean importance. Therefore, the first thing to assure yourself of is that you are not the square peg screaming to get into the round hole. There is nothing so warping as that egotistical ignorance which feels itself fitted for whatever position it desires without question or further effort.

To me the most startling difference between the Americans and the English is this—that the English never boast of their attainments or prowess, in words, because for hundreds of years they really have been supreme among the nations, and so now they are simply filled with the belief that this is still the case, and therefore that it is unnecessary for them to try to learn anything new; on the other hand, the Americans boast in words continually that they are already ahead of the rest of the world, while using their clever brains all the time to pick up from every other nation equipments which will eventually make them so.

I leave it to your own powers of deduction to decide which, at the present stage of the world’s rapid evolution, seems the more likely to win in the end! But we are not now going to talk of the national characteristics of your two parents—I merely use this as an illustration of what I want to teach you so that you may have the advantage of knowing how to cultivate the good side of both. The thing to aim at is to make yourself fit for whatever position you aspire to, and to keep your receptive faculties always on the alert to continue to acquire good things even when you have obtained that position. Then you will never need to demonstrate your supremacy in words, every human being who comes in contact with you will see it. And you will have the dignity of the one country and the ability of the other in your possession.

The advice which was generally given to girls was a mixture of altruistic idealism coupled with the intention to throw dust in their eyes upon most of the facts of life.

We have fortunately changed all that now. But, before we come to any material points, we shall have to get down to the bedrock of the main principle of life which is our religion. And I do hope, Caroline, that I shall not bore you by speaking of this—for my religion, and the one I want you to believe in as yours, is a very simple one, and will not take me long to explain. You see, we cannot possibly go on until this point is settled, because it is the key to all others.

I believe I had better enclose you a dialogue I once wrote when strongly under the influence of the style of Lucian, that later Greek master of inimitable cynical humor. Your appreciation of style and your sense of humor, I trust, have been cultivated sufficiently to be able to grasp the fact that a reverent and divine belief is wrapped up in what at first reads as flippant language. I wrote a number of these dialogues upon all sorts of subjects when I was in the same mood, and, if you like them, and understand them, I can send them to you from time to time, to illustrate my meaning, for the finishing of your education, and the perfecting of your armory of weapons which must be of a sort which is not obsolete for the fight of life.

All godmothers writing to their godchildren—and indeed all women writing to the young—are very apt to be dreadfully serious and to give them only the heaviest fare, which must inevitably weary them. Now, Caroline, there is not going to be any of that kind of thing between you and me, because my aim is not to show you how many stereotyped moral sentiments I can instill into you on orthodox lines—but it is to try to prepare you for that place in the social sphere which you have a right by accident of birth and fortune to expect. And, above all, my aim is to try to help you to gain happiness spelt with a big H—as happiness is obtainable in this hour of the world’s enlightenment. It is not always possible for older people to secure it, because, when they were in the gloomy retrogressionist atmosphere which held sway in their younger days, they laid up for themselves limitations which may take them all their lives on this planet to get through.

You, Caroline, have not had time to incur any serious debts to fate, so you have a real chance to achieve the desired end, and so progress in body, soul, and spirit. Now read the dialogue.

Elinor: Very well, my good friend, let us begin by discussing religion then, and from there we can branch off to other matters which come up, and, as you are here merely to make a few remarks, I gather, and leave the hard work to me, I consider I have the right to select my subjects—and I choose religion to begin upon.

John: I’ll do my best to listen, but women are illogical beings, and you will pardon a yawn now and then.

Elinor: All I ask is good manners—conceal your yawn behind a respectful hand.

John: Begin—as yet I am all attention!

Elinor: My religion is very simple. It started by being a rebellion against the narrow orthodoxy which I had been taught in my youth. I refused to credit the idea that we were all born miserable sinners. I felt that we were glorious creatures who should stand upright and rise into space. I resented the attitude of all saints and martyrs as depicted in statuary and painting—a mea culpa attitude—a pleading for the charity of some omnipotent being to overlook a personal fault—as it were to say, “If I grovel enough your vanity will be appeased and you won’t punish me.” I looked round at the glorious world of nature and at the wonder of my own body, full of health and vitality, and I wanted to cry aloud to God, “Dear God, I am so glad you have made me, and I mean to do the very best I can for your creation in return.”

John: That is not altogether a bad idea.

Elinor: I felt that human beings, because of their gift of articulate speech, were different to animals, and had been given a higher spark of the divine essence in their possession of the loan of a more responsible soul. I seemed to realize that we had no smallest right to soil it or degrade it, since God need not have lent it to us at all if He had not wished. We were, so to speak, on our honor with the thing. I suddenly understood that it was unspeakable disgrace to commit paltry actions just because people would not know about them—that even if one had to admit the necessity of bluff in the affairs of men sometimes it was perfectly childish to use it in dealing with God—and not only childish, but useless.

John: You would be honest with God! Tut, tut!—a pretty state of things! A theory like that could upset the world.

Elinor: Tant pis!—I am not talking of expediency. I am stating my beliefs.

John: Go ahead.

Elinor: I felt that because we had received this divine triple loan from God of understanding, apprehension, and emotion, with its branches of deduction, critical faculty, and appreciation—all things beyond the material—we at least owed Him something in return. You will admit, I suppose, that decent people do not accept the loan of a friend’s house and then utterly neglect and defile it?

John: It would be in shocking taste.

Elinor: Then doing the thousand-and-one actions which defile the soul are in shocking taste also. Don Quixote was infinitely nearer a true knowledge of the obligation entailed by the possession of this loan than any of us modern people!

John: Oh, heavens! are you going to drag in fictional characters to illustrate your tirade? I feel the yawn coming.

Elinor: Then I will state what to me are the facts of religion. I believe that I personally, and each one of us, have received from God, for the term of our sojourn on earth, a spark of Himself, and, since He has had the intelligence to construct this planet and a number of others, He cannot be so wholly wanting in logic as deliberately to throw this spark of Himself into temptation, and then deliberately to punish it for falling. If I believed God capable of that I should utterly despise Him.

John: It sounds mean.

Elinor: Of course. Now think a moment. Each unit being a part of the eternal scheme, the soul of each unit being a spark of the Divine Consciousness, it follows surely that the basis of all religion is that we must not soil our souls—not from the fear of hell or hope of heaven, but because they, being lent by God, must return to Him untarnished. The law of cause and effect takes care of the punishments or rewards. We bring each upon ourselves by our own actions; setting in motion an inevitable machinery producing consequence, as surely as when we thrust our hand into the fire it is burnt.

John: That sounds all right; go on!

Elinor: You see, then, our setting in motion this law can have nothing to do with the anger or approval or complacency of God. “Be good, and you will go to heaven: behave evilly, and you will go to hell”—one was taught. Reward and punishment—personal gain or personal pain—which gets it back to pure selfishness.

John: Then you would take away these strong motives to influence human conduct? You are getting on to a high plane!

Elinor: I began by saying we were talking of religion; you seem to consider we are discussing a business concern.

John: So it is—put it how you will.

Elinor: I deny that from my point, but I admit it if you are going to traffic with rewards and punishments.

John: Then you mean to tell me that each unit is always to behave in the purest manner and do his level best simply to return to God at death an untarnished soul?

John: But you would do away with all priestcraft, all politics, all society! ’Pon my word, this is worse than Socialism. You know I never bargained for that!

Elinor: Nothing of the kind! The basic principle is that God is omnipotent. Granted this, and the poorest intelligence might then credit Him with having the best of all the attributes with which He has endowed mankind, whom he created—chief of these being common sense.

John: Go on.

Elinor: It is hardly likely, then, that He is perpetrating a colossal joke upon His creation by making the whole system experimental. It is conceivable that a brain which could evolve the intricate organism of a minute ant might be far-seeing enough to devise an immutable law which, when our evolution is sufficiently advanced, we shall be able to perceive, and to fall in with its action.

John: We are all as yet struggling in the dark, then?

Elinor: More or less. You see time is no object to God—these cycles which to us mean so much may be no more than a day to Him. I think you will admit we have let in a good deal of light in the last hundred years or so.

John: Well, yes. But just think, then, of the waste of time all the religions and conventions and superstitions have entailed in the past. It makes one giddy to realize it! Where would we be if we had always understood your basic principle?

Elinor: Nowhere. The evolution of the world has been perfectly necessary, my good John—you don’t ask children to play golf before they can walk.

John: No—but now I gather from your remarks that you would sweep away the incumbrances and restrictions of orthodox religions.

Elinor: Not at all! In a large family everyone cannot be grown up at the same time; the little ones have still to be thought of.

John: I think we are getting a bit out of our depths—had we not better get back to your muttons—in this case your idea of religion?

Elinor: But I have stated it plainly; it is simply to endeavor to keep the soul untarnished so as to return it to God—as a good butler keeps his employer’s silver under his charge highly polished, even though it is not all used every day.

John: Then what is the first step to this end?

Elinor: To think out the reason why of things, to try to see the truth in everything.

John: Good Lord! A fine task! Are you aware, my good woman, that this has been the modest ambition of several million of philosophers and theologians and metaphysicians before your day, and that none of them have altogether succeeded? If I did not mind being rude, I might say, “I like your cheek!”

Elinor: Oh, say what you please! Your words cannot alter my basic principle, which you will find very sound, if you care to apply to it the test of common sense.

John: You mean, to bring it to ordinary facts, that when I can get the better of a friend by a bit of sharp practice and make a pot of money without the risk of anyone’s finding me out, I am to refrain from doing so because of this soul business? I do call that hard! considering I go to church every Sunday, and subscribe to all the charities liberally—and to the football clubs.

Elinor: Yes, I mean that.

John: And when you are jealous of a woman you are not to set about a vile, false insinuation against her, even though it could never be traced to your door?

Elinor: Certainly not.

John: But, my poor child, that would produce a universal state of brotherly love. You had not suggested that before as one of your component parts of religion!

Elinor: John, when God made man I do believe He left out one colossal quality in him—the faculty of seeing the obvious. Women can see it sometimes, but men!—almost never! So I shall have to tell it to you in plain words. God is love!

Now, when you have digested all this, Caroline, I want you to think what that sort of religion really means—and how it must elevate its believers into great broad aims and ends. How it must destroy all paltry meannesses, because, once a person realized that, even if no one on earth could ever know of his small action, his own soul would be aware of it, and become tarnished in consequence—then surely he would hesitate to commit that which would injure his own self-respect.

There is another point to be considered: how best to arrive at what is actually right or wrong. And this can only be done by psychological deduction, through effect back to cause. If the results of an action produce pain and sorrow and evil, then the action—which is cause—must be bad. And, as there is nothing new under the sun—and all actions you would be likely to commit have already been committed by others in the past—you can get a general idea as to their probable result. But, above all other sides, the one to be examined is the effect upon the community. If the result of the action can only affect yourself, then you have the right to consider whether or no you will be prepared to pay the price of it before you commit it. But if there is plain indication that it can degrade or injure others who are near to you, or the community at large to which you belong, then the sin of it “jumps to the eyes,” as the French say.

The test of every action is whether or no it would injure your own self-respect; firstly, entirely for you; and, secondly, in regard to the community—because your self-respect would be injured if you felt you had hurt the community.

You are a responsible being, you know, Caroline, a being with naturally fine qualities, and one who has had the fortune to have received the highest education. Therefore you must “make good,” and show that, when art and science, directed by common sense, have done their best for a young girl, she can prove in herself that it is worth while to use these two things for the perfecting of the coming woman who is to be the mother of that race of mental giants which we hope the middle of this, our century, will produce.

I think I am a crusader for the cause of common sense—which is only another word for what God meant when He endowed Solomon with wisdom. And, as these letters to you go on, you will observe that every single point we shall discuss will be ruled by this aspect.

For the highest ideals are only common sense poetically treated. And now, Caroline, good-night—we have finished this talk upon religion—and need not refer to it again, since I believe your intelligence is such that you have grasped my basic principle. You will hear from me soon upon another subject.

Your affectionate godmother,

E. G.

December, 1912.

I HOPE you were not very bored by my last and rather serious letter, Caroline. I was obliged to begin in that solid way, so that we could be sure of our points of view being the same for future talks, but in this missive I am going to write about something quite different, and almost as important—your manners!

The tendency of the present day is to do away with all gentle things, and among them courtesy has gone by the board, so that to see anyone still with beautiful and gracious manners is a thing to be remarked upon and rejoiced over. And I want you to be among this small company of the survival of other days!

The modern young woman is so innately selfish that, as a rule, her manners are only good when some definite momentary gain to herself makes their display worth while. She is too short-sighted to look ahead and see their value, and she is no longer a proud person remembering what is due to herself, and, therefore, that good manners ought to be the stamp of her breeding. She is often as primitive as a young savage, with a smattering of a fair mental education on top.

Numbers of kind-hearted mothers about forty years ago began to think that their own training had been horribly stiff and cruel, and gave a much greater license to their offspring. Deportment masters and mistresses grew to be less and less in vogue, and ridicule was cast upon the rules that had been in practice for every girl entering society. People began to laugh at numbers of things, a sense of humor was reviving, and it attacked the methods and fashions of “young ladyhood.” The children of those days, who are now mothers of the present young girls, went a step further, with the best intentions, and augmented, by the craze for exercise and out-of-door games, the effect of the lax rules of deportment, so that now one hardly ever sees a really gracious and graceful young girl, and some of them are the most unattractive specimens of youthful females in consequence.

Now, Caroline, I want you to be a cunning creature and combine the methods of the old and the new. If your tastes incline to violent outdoor games, assiduously cultivate beautiful and gracious manners as well, so that the young men you play with, while admiring your skill, will not feel they can treat you as “another fellow,” hardly with courtesy, and with no consideration.

Try not to swing your arms and be ungraceful in walking. Try not to sit in every awkward position that may be comfortable. Do not cross your legs and display yards of ankle, and, above all, do not lean both elbows upon the table and eat as though at a picnic where gipsy’s ways were good enough. One sees all these defects so constantly now that one has almost ceased to remark upon them. The very tight skirts have done one thing for women—they have enormously improved their walk, making those long, manly strides impossible. I suppose no nation in the world has such naturally perfectly-shaped bones and proportions—and no nation spoils these advantages so much by their atrocious movements as we do. Well, what a pity! And why cannot common sense step in and rectify this failing? Why do anything with exaggeration? Why play games to death, turning a pleasure into a grind? All is out of balance; and by these unattractive methods girls have often had to become the seekers, not the sought-after!

You must remember, Caroline, that you will be in a country where women are in an enormous majority—and the effect of this is that the men, unconsciously and naturally, have a great idea of their own value. It is not their fault, or because they are particularly vain men; it is simply because there are so few of them and so many of us! Therefore, if you want really to enjoy life and count as a coveted quantity, you must rise above the general company of young, unmeaning beings of your sex, so as to make the nice young man you may fancy think of you, not as one of a batch for him to choose from, but as the only desirable creature in all the world for him to strive to obtain. The really interesting thing is to be a personality, not one of the herd. And I would like to see you, Caroline, with your beauty and your position, starting a new fashion in young girls when you come out. For, my dear child, realize one thing,—all the stuff and nonsense which you may have been told about women fitting themselves for a self-sufficing existence, and their “rights” and their assertion of equality, are pitiful makeshifts, of use only if the poor things do not obtain the sole real joy and happiness—to be the loved and honored mate of some nice man. If, by your self-assertion and exaggerated mentality, you have been able to crush out all sex instinct, then you become as the working bee—of a third sex, an anomaly in nature, and a ridiculous excrescence in God’s scheme of human progression. So for heaven’s sake, my sweet Caroline, keep this in view. Train what individuality in yourself you will, but keep your clear perspective so as to be able to see the ultimate goal of happiness.

I think I have been rather generalizing, so now I want to come down to a concrete description of what I think would be a perfect young girl, and you must tell me if you agree with this picture of a female “admirable Crichton”! I think, firstly, she ought to be sensible enough to understand the colossal

importance and value of beauty, and to have learned to take care of her personal appearance, so that in every way she is a pleasure to the eye. She ought to have discovered early what style of garments suits her; she should have practiced until she can do her hair becomingly; and by exercises, and by care in remembering what is ugly and to be avoided, she should have perfected the grace of her body’s movements. All these things having been looked upon, not as vanities, but as the natural polishing of the body God had entrusted her with, as the shrine for her soul.

Her voice should be soft, and her cultivation at least sufficient—should she not be naturally clever—to make her know the topics of the day which are interesting to converse upon; and she should be broad enough not to be prejudiced about any of them.

Unselfishness in her should go as far as not to want always to have her own way, regardless of whom it hurts or discomforts. (One could not expect more than that in these days!)

She ought to have so high a respect for herself that she could never make herself cheap, but she should also have common sense enough to realize that, because it is, numerically, such an unequal fight between the sexes, she must have her weapons of attraction peculiarly well polished. Then, out of the limited circle of possible husbands she will have to choose from, she may hope to attract the best—because like clings to like.

As she is my ideal young girl, she will not be stupid enough to set out with the idea of making her own life self-sufficing. Whatever circumstances may force her to do afterward, at least to start with she will know that to be happily married is the natural goal, and that to obtain this good thing she must take care of her equipments and fit them for the post she aspires to.

She must have tact and a highly cultivated sense of humor, so that she may not be a bore with her notions and her egotism. She must not stand against the times, but be so ruled by fine taste that she cannot be drawn into any exaggeration.

Her ambition is to become the inspiration and adored mate of whatever nice man she may marry, because, as she is very highly refined and balanced, she will not be attracted by the weakling or the fool, whom she would inevitably rule while she despised him.

If she finds that somehow she has drifted into union with one of these beings, then it will be time enough for her to assert her supremacy—and the more self-controlled and equilibrated she is, the more successfully will she be able to stand alone if necessity requires her to do so. But, Caroline, remember that the natural goal and the happy and glorious goal of a woman is to strive to be the refining influence, the inspiration and the worshiped joy of a man. When she has to be self-sufficing, then, no matter how great she may become, the happiness is only second-best. So as you have youth and a clear sky, child, I want you to set forth with a desire for this best and greatest happiness.

There are splendid and suitable young men coming on every year, so this should not be an impossible attainment. Do you remember what Tennyson wrote about King Arthur making his knights swear this vow after the others?

Now, even with your limited experience, Caroline, I am sure you will agree with me that there are very few modern maidens who are able to make a young man desire to shine in any of these ways. They do not inspire him with much reverence for themselves, or even much love!

Often the most they can make him feel is that they play a good game of golf, or that they “aren’t bad sorts,” or something of that kind. For you must not forget that whatever the other person thinks and feels about you is what you yourself have given him the presentment of. It

entirely lies with you, therefore, what impression on his heart and brain you wish to create. I do assure you, Caroline, that it is infinitely more agreeable when he thinks you all that is perfect, and is passionately in love, than when he is mildly attracted by your golf and your camaraderie, while his unemployed senses, left at liberty to roam, stray to the more cunning young women of the chorus, who have realized that some feminine allurements are not bad things to cultivate. By all means play your golf and your tennis if they give you pleasure, but try and make your partner feel that these things are a means to securing the end he desires: namely, your company and companionship; not that you are the means to his enjoyment of the game. Do not throw away all mystery and appear a loud, jolly schoolboy, because, if you do, naturally the other “boys” will treat you as one of themselves, or as a sister—not as “another fellow’s sister,” to be considered, and whose favors are to be schemed for.

There used to be an idea that girls must be warned about wolves in sheep’s clothing, who wandered in society ready to lead them astray, corrupt their morals, and break their hearts! But, if these fabulous creatures ever existed, they only survive now in a few daring, youngish married men who make it their business to flirt with girls. I need not warn you against these, Caroline, because

I know that you are a proud little lady, and one, therefore, whose instincts would tell you that the attentions of a married man were merely an insult, disguised in whatever form they happened to be. It is only the lowest and cheapest sort of girl who willingly encourages such people, blazoning to the world that her vanity is colossal and her self-respect nil. So we need not touch more upon this subject. If a man is not free to marry a girl, his assiduous attentions are an impertinence, to say the least of it.

Owing to the scarcity of men, as I said before, they are inclined to give themselves airs, and numbers of young women do the seeking and the hunting, while the poor youths are scared of being captured, and, when they are secured at all, it is unwillingly. Must not that be a hateful blow to the girl’s pride when she thinks of it!

The legitimate way is to render yourself as utterly desirable as possible, and then fate will bring you the particular needle your kind of magnet draws.

There are all sorts of points about manners which add to a girl’s charm. When you come into a room pay respect to elder people; it will not take up much of your time, and is a gracious tribute of youth to age. And when you go out to dine or lunch do not sit silent if you happen to be bored with the person who is next you; you owe it to your hostess to try to make things as agreeable as possible. And when you stay about in country houses remember this also: You have been asked because the hostess likes you, or you are a credit to her, or she is under some obligation to return some civility from your family. In all three cases you ought to make good by proving you are a most desirable guest. Try to acquire prestige, so that none of the nicest parties are complete without you; then you can choose which you prefer to go to. But prestige is not acquired without tact and perfect manners on all occasions. The tendency of all modern society is toward vulgarity and display, with a ruthless, cynical, brutal worship of wealth, snatching at any means to the end of luxury and pleasure. People accept invitations from those they despise, for no other reason than because they are rich and the entertainment will be well done. It is awfully cheap, is it not, Caroline? and a long way from my basic principle which I explained to you, that one must not in any way degrade oneself. Try to be kind to everyone you come in contact with and make them feel at home, however humble they may be, if they are your guests; be gracious and thoughtful for their comfort and pleasure—you need never be familiar or gushing. Be simple and modest; all pretense is paltry and all boasting is vain; nothing but the truth lasts or gains any respect.

I should like to tell you a little story, Caroline, before I finish this letter, as an instance of really exquisite manners.

A year or two ago I was staying in the North with a very great lady; we were all going in to Edinburgh for the day. My friend was a little short-sighted, and while we stopped at the bookstall before crossing over the viaduct to the departure platform I noticed a rather humble-looking little woman nervously and anxiously trying to bow to my hostess, who did not perceive her. After we had mounted the stairs and crossed the line her daughter told my great lady of this, and how Mrs. Mackenzie, the new doctor’s wife, had looked quite hurt. My friend was so distressed that she made an excuse to return to the bookstall, so that she might casually pass the little woman again and bow and speak, but not to hurt her feelings by making her feel she had done it on purpose. I went with her, and while buying an extra paper she glanced up sweetly at the humble-looking little woman, and said:

“Oh! how do you do, Mrs. Mackenzie? I hope your little children are well, and the Doctor; so glad to see you are quite recovered from the influenza I heard you had,” and then, with a gracious smile, she drew me on, and we had to run back up the stairs to be in time for our train. Such manners as these are the only true and beautiful ones, Caroline, because they spring from a kind and tender heart.

Your affectionate Godmother,

E. G.

January, 1913.

I HAD meant, my dear Caroline, to write to you upon the interesting subject of marriage in this letter, but before I can commence upon that, I must speak of something else, and you must promise me not to be offended at what I am going to say, since we both desire the same end—your success and welfare. The fact is, your picture, which you tell me was drawn by a friend, has just reached me. You say it is more like you than the only photograph I possess of you, taken when you were fifteen; and it is because of your assuring me of this that I cannot remain silent—for, Caroline child, I must confess it shocks and disconcerts me, and makes me feel that I must be very frank with you, if you are ever going to be able to attain that position which we both hope that you may.

Even if the drawing was perhaps done some months ago, and you have altered your style of hair-dressing since then—still, that you were ever able to have looked like that—you in Paris!—proves that your observation and taste are not yet sufficiently cultivated to make you anything of a success when you come out in May. Thus I must speak plainly and at once.

Now, let us pretend that the little girl I see before me is not you at all, but some abstract person; and let us dissect her bit by bit: her type, her style, her suitability—or want of it—her attitude and the general effect she produces. And then let me suggest the remedies and alterations which can improve her.

Firstly, her type, Caroline, child, is not distinguished. She has a large-eyed, dear little profile, which may be very pretty as a full face, and which, framed in appropriately done hair, could succeed in being picturesque, but in itself, with its little snub features, is insignificant. She has rather a big head, and thick, bushy dark hair—which I grieve to observe she has done in a large bun of sausage curls!—a fashion which was never in vogue really among ladies, and for over two or three years has been relegated to the pates of “roof-garden” waitresses and third-class shop assistants. And further to provoke my ire, although this girl in the picture is drawn in an ordinary morning skirt and boots, she wears a light-colored ribbon in her hair! Caroline, dearest, where could her eyes and observation and sense of the fitness of things have been—with the example of the exquisite Parisiennes in front of her—to be able to perpetrate these incongruities! But there is more to come! Her skirt is a rough, useful serge skirt, and her boots, although the heels are too high, are not a bad shape—but with this she has put on one of those cheap, impossible blouses, cut all in one piece—“kimono,” I believe they are called—with short sleeves and an unmeaning black bow tacked to the cuff! Now, a shirt should be a workmanlike thing, as neat as a man’s, and with long sleeves finished by real shirt-cuffs with links. It can be composed of silk, flannel, or linen, but if it is a shirt—that is, a garment for the morning, and to be worn with a rough serge or tweed winter suit—it should have no meaningless fripperies about it. If you want trimmed-up things, have a regular blouse, and then wear it with an afternoon costume. Short-sleeved blouses should only be indulged in in the summer, and when they are made of the finest material. And even then, if the wearer has what the little girl in this picture seems to have—thick wrists and rather big hands—it is wiser to avoid them altogether!

Now that I have torn her garments and hair-dressing to pieces, Caroline!—I must scold about her attitude. She is doing two of the most ungraceful things: putting her arm akimbo and crossing her legs! You may say every girl does them—which may be true, but that is no proof that they are pretty or desirable habits! To digress a moment—I went to a party the other night, a musical party where the guests were obliged to sit still round the room quietly; and I counted no less than thirteen of the younger women with their legs crossed, which in some cases, on account of these very narrow skirts we are all wearing, caused the sights to be perfectly grotesque. There is something so cheap about exposing one’s ankles, to say nothing of calf, and almost the knee, to any casual observer—don’t you think so?

But now to return to the girl in the picture! We have dissected the details and got to her style, and the effect she produces. Her style, I must frankly say, is common, Caroline, and the effect she produces is unprepossessing, because it is incongruous; and incongruity in all simple, morning, utility clothes is only another word for bad taste. I could write pages and pages about the vagaries of fashion, and how what looks chic one year may be vulgar the next, but we have not time or space for that. There are only these general rules always to be observed: for the morning or the street, the most distinguished-looking woman or girl is she who is garbed the most simply and the most neatly, with tidy hair and every garment plainly showing its purpose and meaning. It is in this that the Americans you can see any morning walking on Fifth Avenue excel. But, alas! English maidens nearly always spoil the picture by some unnecessary auxiliary touch or other.

Now, Caroline, be just, and, looking at the drawing with an unprejudiced eye, you will admit that what I have said, though severe, is true.

With a type like yours you cannot be too particular to be on the side of refinement and good taste, and my first advice is: Brush all that thick bush of hair so that it shines, then part it and take the sides rather farther back, so that they do not touch your eyebrows (I like the tiny curl by the ear which has escaped—leave that!); then twist all those dreadful sausages into the simplest twist, so as to make your head as small as possible—which, apart from being the present fashion, is a pretty balance. Never wear a light ribbon in the day-time, although it often looks very becoming at night.

In choosing an article of dress you must remember the vital matter of its suitability; suitability generally, suitability for the occasions you mean to wear it on, its suitability to yourself and your type. If you cultivate these points and use your eyes and observation to see what is the prettiest note in passing fashion, you can counteract the rather commonplace, though pretty, appearance Nature has endowed you with, and turn it into a quaint, picturesque little individuality.

Never buy things that you do not actually want just because they are cheap. Cheap things nearly always have disadvantages, or they would not be cheap. Have few clothes and good ones. Take care of them, and do not ruthlessly crush and rumple them when you have them on, even though you have a good maid to repair your ravages afterwards. I know you will not have to bother about money, but I say all this because I see by the blouse you are wearing in your picture that you have a leaning toward these rubbishy things. Be extremely particular about your foot-covering, too, Caroline. You look as though you had nice feet. Never buy any of the eccentric fashions that you see in every shop window, and on the feet of every little person trotting in the street. Go to one good bootmaker and let him make a study of your foot, and then have the simplest, neatest, and daintiest things made for you. You see, I am writing to one who has ample money for whatever is required, so I am giving her the best advice, because I fear her own taste is not sound—and she is young enough to learn! If you were a poor girl, Caroline, coming out in society on the narrowest means, I would send you all sorts of hints how to arrange and manage to look sweet and lovely upon a very small sum. It is not that all cheap things are ugly, but, with a faulty taste and a large allowance, it is wiser for our end that you should go only to the best shops. I implore you, Caroline, if the instinct of personal distinction does not come naturally to you, to cultivate it by observation. Every time you go out observe what women look the nicest, and what makes them achieve this effect. Examine your own little face, with its blue eyes and black hair, and try to imagine which of the styles would suit you best and make you look the least ordinary.

You have probably never thought of these things, and have just drifted on with other school-girls until you present the mass of incongruities your friend depicted in the drawing of you. I am extremely grateful that you have sent me this sketch now, when it is not too late, and we have still some months before us to alter matters. And your letter in answer to my first one shows me that you have a charming nature, and will understand this which I now write and take it as it is meant. Exaggeration is one of youth’s faults, and easily corrected and trained.

And now we can begin about marriage. But, as the post is going, I shall not be able to say all that I want to in this letter.

Marriage is the aim and end of all sensible girls, because it is the meaning of life. No single existence can be complete, however full of interests it may be. It is unfinished, and its pleasures at best are but pis-allers. You agree with me on this point, so we need not argue. But marriage in this country is for life, unless it is broken by divorce, which, no matter how the law may be simplified, and altered presently, must always remain as a stain upon a woman and a thing to be faced only in the last extremity. So, Caroline dear, when you marry you must

realize that it is for life, and it is therefore a very serious step, and not to be taken lightly. The rushing into unions without sufficient thought is the main cause of much of the modern unhappiness. How can you expect to spend peaceful, blissful years with a man whom you have taken casually just because you liked chaffing with him and dancing with him, or playing golf? Think of the hours you must spend with him when these things will be impossible, and if you have no other tastes in common you will find yourself terribly bored. In one of my books I once wrote this maxim: “It is better to marry the life you like, because after a while the man does not matter!” It was a very cynical sentence, but unfortunately true. It is only in the rarest cases that “after a while” either individual really matters to the other. They have at best become habits; they are friendly and jolly, and if “the life” is what they both like all rubs along smoothly enough. But love—that exquisite essence which turned the world into Paradise—is a thing flown away.

Now, Caroline, I want yours to be one of those rare cases where love endures for a long time, and even when it alters into friendship continues in perfect sympathy.

So, when you feel yourself becoming attracted by a young man, pull yourself together in time and ask yourself, if the affair goes on, would you really like him for a husband?

Think what it would be to be with him always, at the interminable meals, for years and years, through all the tedious duties which must come with responsibility. Ask yourself if his tastes suit yours, if his bent of mind is the same, if you will be likely to agree upon general points of view. And, if you are obliged honestly to answer these questions in the negative, then have the strength of mind to crush whatever attraction is beginning to spring in your heart. Once it goes on to passion, no reason is of any use, so it is only in the beginning that judgment can be employed.

You must remember that like draws like with more or less intensity according to the force of

characters. I know you are highly educated, Caroline, and if you do not let yourself become priggish you should draw a very nice young man. Then let us suppose you have done so, and marry him. You are then contracting a bargain, and you have to fulfil your half. The modern young woman seems to imagine she has done quite enough by going through the ceremony, and henceforward she is to do exactly what she pleases, and only consider her own pleasure on all occasions. This attitude of mind makes things very hard upon the poor young man, who presently gets bored with her, and, as in these days honor and rigid morality are rather vieux jeu, he soon drifts away to other interests and amusements. And one cannot blame him. It is upon your obligations and behavior, not his, that I wish to write to you at length, Caroline, but in this letter I shall have time only to begin. You must start by understanding that the natures of men and women are totally different. Men are infinitely more simple, and the British education helps them by its drumming into their heads the knowledge of what is or is not “cricket.” Their natural methods are more direct, and they are much easier to deal with. They are fundamentally and unconsciously selfish, because for generations women have been taught to give way to them. You must accept this fact and not storm and rage against it. The only way you can change it in regard to your own personal male belonging is by inspiring in him intense devotion to yourself; but, even so, it is wiser to face it and make the best of it, and not be disillusioned. You are probably selfish also; it is one of the greatest signs of the age, the growing selfishness of women. It is not altogether a bad thing; it is a proof in one way of their increasing individuality; but meanwhile it does not tend toward their happiness. Now, Caroline, I am sure you will agree with me that to aim at happiness is a wiser and more agreeable thing than just to express the growing individuality of your sex!

I must reiterate what I said in my former letters; I am advising you for a first start in all things. Circumstances may arise which may alter possibilities, but, to begin upon, we may as well aim at the best, and not fight windmills; storming that men ought to be different, and that women should not give way, being their superiors in most things!

It will take much longer than your lifetime (and I personally hope, in spite of the wrath I shall excite in stating this,—much longer than many lifetimes) to change the nature of men. So do not let us bother over these abstract points, but accept men as they are, dear, attractive, selfish darlings! with generous hearts and a quite remarkable faculty for playing fair in any game. So you must play fair also, and try to understand the rules and follow them. If the husband you select has a stronger character than you have, and if he is also extremely desirable to other women, the only way you will be able to keep him through all the years to come will be by being invariably sweet, loving, and gentle to him, so that, no matter what tempers and caprices he experiences in his encounters with the many others of your sex who will fling themselves at his head, he will never have a memory but of love and peace at home. Never mind what he does, supposing you really love him and want to keep him, this is the only method to use. It may even seem to bore him at the end of about the first two years, but continue.

If he is young and handsome and attractive he must have his fling, and you should let him have whatever tether he requires, while you influence him to good and beautiful things, and always know and feel certain in your heart that the intense magnetic force of your love and sweetness will inevitably draw him back the moment the outside fascination palls. These preliminary remarks, I dare say, are calculated to provoke the fiercest argument among many girls; but wait, Caroline, until I have finished explaining the reasons and dissecting the aspects, keeping in view our end—common sense and happiness.

You must tell me if these things interest you before next month, when I will write again. Because now I must end this letter.

Your affectionate Godmother,

E. G.

February, 1913.

IAM so glad, my dear Caroline, to hear that you were interested in my last letter. It is an important subject—marriage—and one I want more fully to discuss with you. No one accomplishes any rôle successfully without some preparatory training—and the rôle of a married woman requires a good deal of thought bestowed upon it before it should be undertaken.

As I said in my last epistle, the affair is a bargain, in which too often the modern young people refuse to recognize any of the responsibilities. Let us, for the sake of our argument, suppose, Caroline, that you have fallen in love with, and married, what appears to be a suitable young man in fortune and character. We will pretend that he is the eldest son of some one of importance, and in his turn one day will occupy a great position. If you have carefully followed the advice I have been giving you, you will be so distinguished in appearance and manner that you ought to be an ornament to your new station. And you must make your husband feel from the very beginning that you mean to take the deepest interest in all his tastes and pursuits: if they are political, that you will endeavor to forward his interest and understand his aims; if they lie in the country and the management of his estate, that you mean to fulfil all the duties which such an existence requires. If he is a soldier, a sailor, a barrister, a financier—no matter what—this same principle applies, though in the latter professions you cannot take perhaps such active interest; but you must show him that at all events you can give him your sympathy and understanding, and make his home pleasant and agreeable when he returns to it. If you make it smooth and charming for him you may be as certain that he will prefer to spend all his spare time with you as that he will break away immediately if you do not.

All human beings unconsciously in their leisure moments do what they like best. If you find a man in his free hours doing something which he obviously cannot like, it is because to accomplish his duty is the thing he likes best. Thus, if you bore your husband in his leisure, he may stay with you for a while from a sense of duty, but he will begin to make excuses of work to curtail the moments, and he will snatch time from his real work for his pleasure elsewhere.

Whether you keep your husband’s love and devotion lies almost entirely with yourself and your own intelligence, and I might say sagacity! Remember this maxim: “A fool can win the love of a man, but it requires a woman of resources to keep it”—the difficulty being much greater in a country like England, where the women are in the majority, than in another where they have to be fought for, and the men are the more numerous.

We will suppose that you desire to retain the love and devotion of your husband, and have not only married him for a home and a place in society. In this case face the fact that it is always a difficult matter for a woman to keep a man in love with her when once she belongs to him, and he has no obstacles to overcome. For man is a hunter naturally, and when the quarry is obtained his interest in that particular beast wanes, although the interest in securing by his skill another of the same species remains as active as ever.

The wise woman realizes all these primitive and deep-seated instincts in human nature, and adapts herself to them. She recognizes the futility of trying to make her personal protest effective against what is a fundamental characteristic of all male animals.

Who, seeing a wall with several gates in it, would be so foolish as to fling herself against the stones instead of quietly going through one of the openings, simply because she resented the wall’s being there at all! And yet this is what numbers—indeed the majority—of women do, figuratively, in their dealings with men; and so destroy their own happiness. But I want you to be wiser, Caroline. Realize when you embark upon matrimony that you will have to play a difficult game, with the odds all against you, and that it will take every atom of your intelligence to win it, the prize being continued happiness. You may reply, “If Charlie requires all this management and thinking over, let him go! I would not demean myself by pandering to such things.”

And I answer, “Certainly, if to let him go will make you as happy as to keep him!” But if, on the contrary, it will make you perfectly miserable, then it will be more prudent to use a little common sense about it. Ask yourself the question frankly and then settle upon your course of conduct.

If you decide to try to keep him, attend to your means of attraction. While you were engaged to him you would not have allowed him to see you looking ugly or unappetizing for the world—such things are even more important after you are married. Never under any circumstances let him have the chance of feeling physically repulsed—for the very first time he experiences this sensation that will be the beginning of the end of his being in love with you, although he may go on treating you in a very kind and friendly way. But if you want to keep him in the blissful state, attend far more to pleasing his eye and his ear when alone with him than to pleasing the world when you go out. Let him feel that whatever admiration you provoke—and the more you do provoke the better he will love you—still that your most utterly attractive allurements are reserved as special treats for himself alone. If I were able to give girls only one sentence of advice as to how to keep their husbands in love with them, I should choose this one—Never revolt the man’s senses. For, remember, this particular aspect of affection called being in love is caused by the senses of both participants being exalted. He is moved by what he thinks he sees in his beloved, and she likewise; and, if the realities are far below the mark of his or her imaginary conception of them, so much the more careful should each one be to keep up the illusions. Very deep affection can remain when all sense of “being in love” is over, but it has lost its exquisite aroma of sweetness.

A man will go on being in love with even a stupid woman who never fails to please his eye and his ear—whereas he will lose all emotion for the cleverest who revolts either. Grasp this truth, that the personal attraction in a connection like marriage is of colossal importance, for the moment that is over the affair will subside into a duty, a calm friendship, or an armed neutrality. It can no longer be a divine happiness. So if you can keep this great joy by using a little intelligence and forethought, how much better to do so! I hope you agree with me, Caroline?

your husband will meet will only be showing their most agreeable sides to him without the handicap of daily intercourse. Remember, also, that, though he may have the most honorable desire to be faithful to you in the letter and the spirit, he cannot by his own will suppress or increase his actual emotion toward you, and if you destroy his ideal of you it cannot be his fault if his ardor cools. That is one point of gigantic importance which I want to hammer into your head, child—whatever a person thinks and feels about you, you yourself are responsible for. You have given his or her sensibilities that impression, exactly as when you look in a mirror your reflection is reproduced.

People complain of being misunderstood, but it is because they themselves, unconsciously perhaps, have given the cause for misunderstanding. A girl may say a man is a brute and a false traitor, because in May he was passionately loving, making every vow to her, but by October he had cooled, and by December he had become in love with someone else! Granted that some men have fickle natures and more easily stray than others, still the actual emotion for a particular person is not under any human being’s control, only the demonstrations of it. I must be very explicit about this statement in case you misunderstand me.

I mean that no man or woman can love or unlove at will—(by “love” I am still meaning all the emotions which are contained in the state called “being in love”). This state in man or woman is produced, as I said before, by some attraction in the loved one, just as a needle is attracted by a magnet. If the magnetic power were to lessen in the magnet the needle could not prevent itself from falling away from it—or if another and stronger magnet were placed near the needle it would be drawn to that. It—the needle—would only be obeying natural laws and therefore would not be responsible.

Which, then, could you blame—the original magnet or the needle?

Obviously the magnet is responsible.

You may reply. But the magnet did not wish to lessen in attraction; that and the arrival of the stronger magnet were pure misfortunes and accidents of fate.

Granted—but this only brings in a third influence—it does not throw the blame upon the needle. So I want you to understand, Caroline, that if a man ceases to love you it is your own fault—or misfortune—never his fault; just as, if you cease to love the man, it is his fault or misfortune, not yours.

These are truths which ninety-nine women out of a hundred do not care to face. But the wise hundredth, realizing that she is the magnet, tries her uttermost to keep her magnetic power strong enough to withstand all misfortune or the attacks of other magnets—that is, if she wishes to keep the man who is the needle.

And if he leaves her she must ask herself how she is in fault. She must never blame him. If she cannot discover that she is in fault at all, she is then in the position of the first magnet—and it is her misfortune; but misfortune can be turned into success by intelligence, and, with skill, a magnet can be recharged.

Now do you clearly understand this argument, Caroline? I hope so, because I have put it plainly enough to make you conscious of your personal responsibility in the matter of being able to retain your husband’s love. So we can get back to the subject of the vital importance of keeping his senses pleased with you. There are numbers of girls who at the end of a month of marriage have done, said, and looked things which they would have died rather than let their fiancés perceive, hear, or see, and yet who are much astonished and feel resentful and aggrieved because they begin to reap the harvest of their own actions in the fact of their husbands showing less love and respect for them.

How illogical! How foolish!

To please a man after marriage every attraction which lured him into the bond should be continually kept up to the mark, because there are, then, the extra foes to fight—the natural hunting instinct in man and the destroying power of satiety. How could a girl hope to keep her husband as a lover when she herself had abandoned all the ways of a sweetheart and had assumed little habits which would be enough to put off any man! If you have done everything a woman can possibly do to be physically and mentally desirable to your husband, and yet have failed to keep his love, you must search more deeply for the reason, and when you have found it, no matter how the discovery may wound your vanity or self-esteem, you must use the whole of your wits to remedy its result if you are unable to eradicate its cause.

He may have idiosyncrasies—watch them and avoid irritating them. He may have some taste which you do not share, and have shown your antagonism to. Try to hide this, and if the taste is not a low one try to take an interest in it. Try always and ever to keep the atmosphere between you in harmony.

If the lessening of your attraction for him has been engendered by the arrival of a stronger magnet on the scene, your efforts must be redoubled to replenish your own magnetic powers. You certainly will not draw him back to you by making the contrast between yourself and his new attraction the greater through being disagreeable. If he outrages your truest feelings, let him see that he has hurt you, but do not reproach him—not because you may not have just cause to do so, but because giving way to this outlet for your injured emotions would only defeat your own end, that of bringing him back to yourself.

You may be perfectly certain that if that aim of your being remains unchanged, and your love continues strong enough to make your methods vitally intelligent, you will eventually draw him away from anything on earth back to the peaceful haven of your tender arms. All this I am saying presupposing that you are “in love” with the man, and the greatest desire of your life is to keep his love in return.

But supposing that his actions kill your affection (this, though, is not so likely to happen as that your actions will damp his—because of that hunting instinct in man making him more fickle by nature)—but supposing it does happen that you find yourself utterly disillusioned and disgusted, then all you can aim at is to obtain peace and dignity in your home, and at least merit your husband’s respect, and the respect of all who know you. But this possibility I must leave the discussion of to another letter; it would be a digression in this one.

The magnet and the needle simile works both ways. If your husband ceases to draw your affection he will only have himself or his misfortune to blame—not you. We have been speaking of emotions hitherto, and of their impossibility of control—and to leave the discussion at that would open a dangerous door to those feather brains who never, if they can help it, look at the real meaning of an argument, but adapt it and turn it to fit their own desires. So I must forcibly state that, although the actual emotion in its coming or going is not under human control, the demonstration of it most emphatically is, being entirely a question of will. A strong will can master any demonstration of emotion, and it is the duty of either the young husband or wife sternly to curb all vagrant fancies in themselves, whose encouragement can only bring degradation and disaster.

I am confining myself now to enlightening you, Caroline, upon your own responsibilities. If your health should not be good use common sense and try to improve it—make as light of it as possible, and do not complain. It is such a temptation to work upon a loved one’s feelings and secure oceans of sympathy, but often the second or third time you do so an element of boredom—or, at best, patient bearing of the fret—will come into his listening to your plaints. If he is ill himself do not fuss over him, but at the same time make him feel that no mother could be more tender and thoughtful than you are being for his comfort. Do not be touchy and easily hurt. Remember he may be thoughtless, but while he loves you he certainly has no deliberate intention of wounding you. Be cheerful and gay, and if he is depressed by outside worries show him you think him capable of overcoming them all. Let your thoughts of him be always that he is the greatest and best, and the current of them, vitalized by love, will assist him to become so in fact.

Think of all the young couples that you know. How few of them are really in love with each other after the first year! They have bartered the best and most exquisite joy for such poor returns—and they could have kept their Heaven’s gift if they had only thought carefully over the things which are likely to destroy it.

I believe you play the piano most charmingly, Caroline—in an easy way which gives pleasure to everyone. Do not, when you marry, give this up and let it be relegated into the background, as so many girls do with their accomplishments. And if your husband should be one of those rich modern young men who seem to have no sense of balance or responsibility, but pass their lives rushing from one sport to another, try to curb his restlessness and teach him that a great position entails great obligations and that he must justify his ownership of it in the eyes of the people who now hold the casting vote in their inexperienced hands. I believe, from the little I know about politics, that I am a Conservative, Caroline—but, when I see an utter recklessness and indifference to their nation’s greatness and a wild tearing after pleasure apparently the only aims of young lives in the upper classes, it sickens me with contempt and sorrow that they should give the enemy so good a chance to blaspheme.

And as women by their gentleness, tact, and goodness influence affairs and governments and countries, through men, a thousand-fold more than the cleverest suffragettes could influence these things by securing votes for women—I do implore you, Caroline, when your turn comes to be the inspiration of some nice young husband, to use your power over him to make him truly feel the splendor of his inheritance in being an Anglo-Saxon, and his tremendous obligation to come up to the mark.

Now you will think I am becoming too serious, so I will say good-night, child.

Your affectionate Godmother,

E. G.

March, 1913.

I FIND I must continue the subject we discussed in the last letter for a little, Caroline, because, besides the question you have written to ask me to answer, there are still some remarks I want to make about marriage which may be for your enlightenment.

You write: “How would it be if the man I were to fall in love with and marry were to be really fonder of me than I of him? Should I still have to use such a lot of intelligence to keep him?”

Now, in reply to that, I want you to remember what I said about the hunting instinct in man. Well, obviously, if he cares more for you than you do for him, that instinct would still be in a state of excitement; so that you would have this very powerful factor upon your side to assist you in keeping your husband’s interest and affection. Marriages are generally much happier when this is the case, but it cannot be arranged—it is a question, one might almost say, of luck. Nothing was ever truer than the French proverb, “Between two lovers there is always one who kisses and one who holds the cheek.” And if the girl is the one who holds the cheek she is fortunate indeed. But for some unaccountable reason, although this often happens during the period of courtship, after marriage the rôles change, and it will be then that the young wife will require all her intelligence to keep what she has learned to appreciate.

And no knowledge of the fact that your husband cares more for you than you do for him ought to make you lessen your determination to be attractive to him. To be absolutely unkind or cruel would not have so alienating an effect as to be unattractive. No woman can count upon her power if she ceases to charm the man’s senses. Should you be happy enough to love a little less than your husband, you may feel that all this analyzing of cause and effect which I have been treating you to does not altogether apply in your case, but still, if you are wise you will take to heart most of it, and so hold what you have won.

Supposing you have returned from your honeymoon still mistress of the situation, and, taking no trouble to please your husband, are just asserting your own individuality and only consulting your own likes and dislikes. Remember you have all your lives in front of you, and that satiety is an ever-present danger. He adores you still—but he will see you every day, and, if you take no pains to please him, that fact will militate against a continuance of his adoration, and you may suddenly realize that he is less eager to worship you—calmer under your caprices, not so disturbed at your displeasure, and you will know that, unless you use every art a woman possesses, your power over his emotions will continue to wane.

There are some weak characters in men who are always ruled by their wives, but of these I do not speak, because no woman ever really loves them from the beginning, and you and I, Caroline, are discussing marriages of love and how to keep the volatile little god an inmate of your hearth and home.

If a girl has married a real man, there are three things she must not forget:

That the man is stronger than she is; that the man is freer than she is; that the man is more open to flattery than she is. And, as he is stronger, so he will break bonds which are irksome to him more readily. And, as he is freer, he will have more opportunity to indulge vagrant desires. And, as he is more open to flattery, so will he be the easier prey of any other woman who may happen to fancy him.

Thus, Caroline, even if he loves you more than you love him, you cannot afford with safety to diminish your attractions for him. For, if you do, it follows logically that he, as the needle, will eventually be no longer drawn to a magnet whose magnetic force has decreased.

Now I want to discuss the two possibilities which I told you last time must be for another letter. The first one was, supposing that you find yourself at the end of the first year

or two utterly disillusioned and disgusted—what then is best to be done? Look the whole situation carefully in the face, and see what roads will lead to better or worse conditions. Above all, do not be dramatic. The ineradicable, insatiable dramatic instinct in some women has caused them, for the pleasure they unconsciously take in a “scene,” to ruin their own and their husbands’ lives. Men are not dramatic: they do not “make scenes”—they loathe them; they loathe exhibitions of emotion which, nine times out of ten, do not occur until some action of their own provokes them, the action having proved that their interest in their wives is going off. The wise woman instantly appreciates this point, and knows that, if she gives way to her, perhaps just, reproaches, she will be adding another millstone round her own neck in a further weakening of her attraction for, and influence over, the man. The wise woman makes quite sure that the matter which has annoyed her is really important—she banishes it if not, and, if it is, she states her case quietly and with dignity, so that her husband can answer her without heat, and give her explanations—or excuses.

She must never forget that the momentary relief and satisfaction of indulging her anger is but a poor consolation when it has produced resentment and repulsion in her husband’s mind—even if, as in the case of our present argument, she herself no longer cares for him. Whatever the man has done, she ought to say or do nothing which can make him feel less respect for herself in return.

If you can keep in front of you always that basic principle which I explained in my first letter, it will guide you on all occasions, and, if you are disillusioned and disgusted with your husband, it will suggest the finest course for you to take. Try to be just, do not repine, admit to yourself that you have lost the first prize in the lottery of marriage, but that there is still the second to be obtained, namely, an unassailable position, your husband’s respect, perhaps the interest in possible children, the interest in your life and your place in the world. And, above all, that inward peace which comes from the knowledge that you at least on your side are keeping up the dignity of your name and station.

You may say all this would be but a very second best, when love had been shipwrecked. I fully admit it, but it is more advisable to obtain the second best than the tenth—or to go under altogether.

Accept the fact that such happiness as you had hoped for is not for you, and decide to be a noble woman and do your duty. Reflection will tell you that whatever you sow you will reap, so, if this misfortune should come to you, keep your head, Caroline, and use your common sense.

Another thing to remember is that you will not always be young, and that many years of your life will probably be passed when the respect of the world, a great position, and the material advantages will count more than the romantic part of love.

And if, through your disillusion and disgust, and the pain of broken idols, you permit yourself to act foolishly and with want of dignity at a period when love seems of supreme importance, you will be laying up limitations for yourself. And it is only the fool who lays up limitations for himself or herself. You will not have got love back by acting so, and you will have lost what might have compensated you in the future. Nothing is more pitiful than the position of the woman of forty-five who has made scandals in her youth, quarreled with her husband and broken up her home, just because she herself was unhappy and the man was a brute. She is then left with none of the consolations of middle age. No one considers her; she is spoken of by her friends and relations as “poor So-and-so.” If she has had children, they have grown up under the wretched conditions of an atmosphere of partisanship for either parent. She is ever conscious of an anomalous position, and has to go through more humiliations than she would have had to do if she had borne bravely the anguishes of the time of trial, and used the whole of her intelligence to better the state of things.

However much a man may turn into a brute, if he has once loved the woman she must in some way be to blame, because love is so strong a master that it can soften the greatest wretch, and if the woman had kept him loving her she would have kept her influence over him as well.

So you can see, Caroline, the tremendous responsibility you will be taking upon yourself when you marry, and how terribly, tragically foolish it will be of you to enter into this bond lightly and without due reflection.

Now for the other subject I alluded to: the permitting and encouraging of vagrant fancies. In these days, when no discipline has been taught girls, and very little principle, they are prone to indulge any caprice which comes into their heads. Good-looking and attractive young women like you, Caroline, are bound to have many temptations to look elsewhere for diversions very soon after they are married. And here wisdom—quite apart from high principle—should teach you to resist as much as possible, because of the end. Ask yourself if it is worth while to start a ball rolling which can only roll down hill—if it is worth while, for the momentary gratification of vanity, to open a door which will let in complete disillusion for the life which you have undertaken to live. Because all forbidden excitements are like drugs—they have to be taken in stronger and stronger doses to produce their effect, until the patient is a wretched maniac or dies under the strain. Suggestion and a strong will are such great helps to happiness. Suggest to your subconscious mind that you are perfectly happy and contented with your legitimate mate—make the current between you one of tenderness and charm, and sternly control every unbalanced fancy. I quote here another of my maxims: “It is a wise man who knows when he is happy and can appreciate the divine bliss of the tangible now. Most of us retrospect or anticipate, and so lose the present.”

Do not retrospect—do not anticipate. Go on from day to day enjoying the good things which fate has given you: ménage them like a careful housewife—use forethought—quite a different thing to anticipation! Recognize that you are happy and decide what makes you so, and how you can continue to employ the methods to keep this joyous state. Be perfectly calm, and believe that nothing can alter or interrupt the enchanting present. For do not forget—each one draws to himself or herself what his or her thoughts dwell upon. Those who lay up for a rainy day attract the rainy day as surely as those who always believe that good will come secure good. A very useful thing for you to do is to look round at all your young married friends, and see what niches they have carved for themselves in the world—which ones are considered and have prestige, which are treated as nobodies, which are laughed at or pitied. Then try to decide upon the grade in public opinion you would desire to occupy yourself, and what are the causes of your friends being in whatever places they are. You will get a number of advantageous hints if you do this before you embark upon marriage yourself.

You will find that simplicity, good manners, and absence of all pretense are things which attract everyone. You will be wise never to be drawn into a set one iota lower than the one you wish to shine in. Weed your acquaintances and remain faithful to your friends. Society is composed, so to speak, of three loops. There is the very common loop which, at its upper edge, slightly overlaps the one above it, so that the best of these common people will just be seen at the worst of the middle loop’s parties. The middle loop, in its turn, overlaps at its highest point the third and great loop, which never mingles with the first and lowest one. You, Caroline, will enter society by the best door, so see that you are not drawn to the lower edge of your loop, and so into the vortex beneath. A large section of the world rave and storm that people are snobs who desire to be in the best society, but they forget that it is entirely the most amusing, the most intelligent and the most desirable, and therefore a very natural goal for newcomers to aim at. The cleverest men go where they meet the cleverest and most entertaining women. And these are naturally to be found among the leisured classes, who have had time to polish all their attractions, who have had money enough to see the world and cultivate their critical faculties, who have learned to dress and to move and to please the eye and ear, and whose abodes provide their guests not only with rich food and drink and spacious rooms, but surround them with an atmosphere of taste and distinction as well. And when you see people with a fine title or great riches commanding no prestige, you may know it is because in themselves they have failed to come up to the standard of what the best society requires. It is also the fashion to say wealth is necessary to a position in society. It may be, if you are only trying to enter it, but it is certainly not the case if you have a right to your position, and are already there. Then, if you have just a sufficiency to swim with the tide, and are charming and agreeable in yourself, you can create a position for yourself and be the desired guest at all the best houses.