| Vol. II.—No. 75. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, April 5, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"Put it back, Jim. Do put it back."

"Why?" Jim whispered, with a startled glance along the wood path. "Is the master in sight, Ned?"

"We are in sight of the Master, Jim."

Jim drew a long breath of relief, and put his finger into the open mouth of one of the unfledged blackbirds. "You frightened me for a moment," he said, "but I see you were only talking Sunday-school stuff. Of course, as Squire's forbid us to touch the nests here, we must mind he doesn't see, that's all."

"Put it back, Jim, lad," pleaded the elder boy, without resenting his companion's sneer. "It's as much a home, you know, as your own cottage; and those four little blackbirds can no more live and grow if you destroy it, than your baby sisters could live and grow if they had no home and no mother."

"I ain't harmin' the mother," muttered Jim.

"Suppose your mother came home one night, after her work, feeling happy, and thinking of the rest she should have in her own snug little house, where you would all be looking out for her, and just when she came close up to your cottage—just at the old lilac-tree by the gate, you know—she looked up and saw there were no little ones to meet her, no bright little room to rest in, no sign, even, of where the dear old home had been: if you could see her then, Jim, would[Pg 354] you say that anybody who'd taken it all away hadn't harmed her?"

"I don't know nothin' 'bout that," stammered Jim, moodily. "It ain't got to do with a nest. The old bird can make another."

"I suppose your mother could find another cottage, but would it be the same without you and the babies?"

"It's very different," grumbled Jim, but a little less defiantly now.

"Father says the mother birds often die of grief when they find their nests gone. You'll put it back, Jim?"

"Not very likely, when I've had all this fuss to get it."

"Just put it back for ten minutes," pleaded Ned.

"And take it again after?"

"Yes, and take it again after—if you like."

"What good would that do?" inquired Jim, with a laugh.

"Just put it back for ten minutes, while I tell you a story."

"You'll promise not to talk Sunday-school stuff when I take 'em back again, or tell the master, or serve me any sneaky trick like that?"

"I promise. Stay, I'll help you put the nest back in exactly the old spot."

"I'll do it myself," returned Jim, ungraciously. "I fetched it myself first, and I'll fetch it again when your tale's over. There, I've put it."

"Look, Jim! look!" cried Ned, joyfully. "That blackbird flying straight to the tree is sure to be the mother. Aren't you glad the nest's there now?"

"Ten minutes ain't very long," observed Jim, as he threw himself at full length on the turf, looking longingly up at the branch on which the nest was built, while the white blossoms of the hawthorn fell upon his upturned face. "I'm safe to have 'em in ten minutes to do what I like with. Now, then, for the tale. Is there a giant in it?"

"Not this time," said Ned, gently. "It's only about myself and the children and mother. That won't be like Jack the Giant-Killer or Robinson Crusoe, will it? But the story isn't long, Jim. I was a very little chap, and the twins were dots of things, and baby only a month or so old. Father worked for the master here, and loved him as all the men do now; but I didn't love him, because he wouldn't have us boys take the eggs or nests. But one day, when I was going through this very wood, and nobody was by to see me, I took a thrush's nest with five tiny throstles in it. I hid it in the basket I was bringing to mother, and went off so cheerfully, remembering we had an old wicker cage at home, and thinking how I'd put the birds in it, and watch how they'd manage to fledge; and how I'd burn the nest—it was dry and crisp, and would burn beautifully—that I mightn't be found out. Mother was sitting by the fire nursing baby (poor mother was sick that time, and baby hadn't ever been well), and I went behind her to the cage, and put my birds in without her seeing, for I knew well enough how she'd tell me I was wrong to disobey the master, and cruel to the little creatures I'd stolen. I didn't care to be told that, for I wasn't sorry, and I didn't want to give mother the chance of spoiling my fun by any of her quiet speeches about the other Master—up there beyond the blue—who cares for every little bird in every tree. I had plenty of opportunities for slipping away to the dim corner where the cage was, for I was let stay up waiting for father; but at last mother sent me to bed. I slept in a little bed in a corner of the kitchen, so it wasn't the same as going up stairs; and I watched the hand of the clock go round, for I couldn't sleep for thinking how queer my orphan birds looked, and how jealous some of the lads at school would be. I saw mother get to look whiter and whiter, and tireder and tireder; but father didn't come home. Then baby began to moan, and mother got up and walked about with her, and I watched how troubled she looked. Then I fell asleep. It seemed like the middle of the night when I awoke, and I jumped up, for I seemed to know in a second that everything wasn't like other nights. The cottage door was wide open, and there was mother standing there, looking out into the darkness, and listening. When I went up to her, she just put her arm round my neck, but she didn't look at me; she only looked into the darkness.

"'Come in, mother,' I cried; 'you oughtn't to stand here while you are ill.'

"But she only stood there trembling, till baby began to cry and move restless in her cradle; then mother came in, and took her up, and held her close to her neck, sobbing as I'd never heard mother sob before in all my life—never. I held to her, and begged her to stop, but I was crying myself too all the time. And still father didn't come. I was a silly lad, Jim, and a wicked one, but I wasn't a coward; and so I begged mother to let me go up to the Hall to ask about father. For a long time she wouldn't, but at last I got her just to whisper 'yes' in her crying, and I was only too eager to set off. She came to the door with me, still shivering, and holding baby wrapped in a shawl; and while she kissed me she whispered something I couldn't hear; but I suppose it didn't matter my hearing, for she was speaking up to Heaven. I wasn't long reaching the Hall, for I knew every inch of the road, and could run safely enough even in the darkness. I went up through the yard, and when I saw a light in the saddle-room, I knew one of the grooms was sitting up to take the master's horse, and I went in at once. It was Tom Harris, and of course I was sorry, because he hated father, and didn't like me; but whoever it had been, I should have gone in then to ask for father. Tom scolded me first for startling him, then he laughed at my questions, and then he got cool again, and stared at me.

"'You won't find your father here,' he said; 'you won't never find him here again, Ned Sullivan, for he ain't ever coming here again. He's turned off. The master won't have nothing more to do with him. You'd best go and ask for him at the public, for he went that way when the master sent him off. The public's a good place for him to forget his troubles in.'

"I stared at the man, trying to understand what he said, and trying to believe him. 'Father never goes to the public,' I stammered. 'What do you mean?'

"'He's never been turned off work before to-night,' laughed Tom. 'That's what sends a man to the public. If he ain't there, something's happened to him. Go you and see after him. Don't stare,' he went on, crossing his arms, and leaning back in his chair by the fire. 'Can't ye hear what I say? Your father's been turned off here, and to-morrow you're all to be off out of your cottage.'

"I caught hold of the table, for the room was spinning round and round; and then I remember Tom laughed, and said it again, as if I'd questioned him.

"'Yes, I mean just what I say. Your father's been late every morning this week, and the master won't stand it—not likely. So you're all to turn out of your cottage to-morrow for the new shepherd. Go home and make as much as you can of the place to-night, as it'll be gone to-morrow.'

"At first I was afraid to stir, for I thought if I did I should fall; but as soon as I could I crept away from the man's sight. Out in the darkness again, all my strength came back, and I ran home faster even than I had run to the Hall, crying mother's name all the way, without knowing what I meant.

"The cottage door was open when I reached it. I think she'd put it open to guide us—father and me; and I looked in, actually afraid for the first time in my life of meeting mother. She was sitting by the fire, her face white, and the tears falling all the time. While I stood wondering how to tell her about father, my sobs burst out[Pg 355] and frightened her. But I was by her side then, and I fell on my knees, and laid my head in her lap. It was just then, Jim, that I remembered my little unfledged birds and their ruined home, and the mother who had lost them, and I folded my hands and looked up into mother's face almost as if she had been God. 'I'll never do it again—never! never! I didn't know it was so terrible. I'll put them back.'

"Afterward, while I told her all that Tom had said, I tried not to see her face, and tried still more, Jim, not to see that old cage in the far corner of the kitchen, where my little prisoners were. When I'd done, mother got up from her seat, and put on her shawl and bonnet.

"'No, no, mother,' I cried, quite quietly, though, for fear of waking baby; 'you mustn't go out; you'll be ill again, and it's quite dark. Oh, let me go!'

"She stooped and kissed me. 'It's no place for you, my child. Take care of baby.' She couldn't say another word, and I could only watch her go, as she had watched me, thinking what I'd have given to be able to go and take care of her.

"I sat close to baby's cradle, and stared into the fire as if that wide stare could keep the tears away; but all the while I didn't see the fire at all, but other things—oh, Jim, so plainly!

"The white light crept through the kitchen window, then the sun rose, and still father and mother didn't come. The sun was shining now, and this was the very day we were to go, so I woke the twins and dressed them, and wrapped baby ready, and put the room in order, all without a word, for I was too miserable to cry. At last father and mother came in, very slowly and silently, and father put his hand on my head, and mother took baby, and then I knew we were bidding good-by to the little home where we had been so happy, and I didn't want to cry, though my heart was breaking, so I crept away to the woods for a few minutes. I felt that everything would seem better there, where I should see the sunshine on the leaves and grass and flowers, and hear the birds' songs among the boughs, making the leaves seem full of music, as I had so often heard them; and even higher still, among the soft white clouds, where I'd often thought that even the angels must like to hear them, stooping to listen when their own songs were silent for a bit. But, Jim, when I came into the wood, there was no note of all these bright glad songs.

"The whole wood was heavy with a dismal silence; and then I knew that it was my fault that the birds were unhappy, and would never sing again.

"What could I do? Was it all too late? Sobbing bitterly, I ran home to fetch the little orphan birds, and give the mother back her children and her home. Ah, Jim, what a change I found in our own dear home! The little kitchen that had always seemed so snug and bright and cheerful was empty and bare. Nowhere in the cottage was there a step or voice to be heard; only I was left there, and with me, in that nest in the old cage, five little dead birds.

"The dream had been so real, Jim, that my cry terrified a gentleman who was riding past in the darkness, and heard it. He dismounted, and came into the cottage kitchen, and I saw it was the master.

"'Were you asleep, Ned?' he asked, in his kind way. 'Did you cry out in your sleep?'

"Scarcely knowing I had dreamed, I told him all about taking the nest, and disobeying him, and about the woods being silent, and how I came home and found our home ruined, and father and mother gone, and the birds dead; and when he looked kindly at me, I fell down on my knees and begged him to forgive me, and not take our home away from mother, but to send only me away, because I'd taken the nest, and to let father and mother and the children stay. Then he questioned me till I'd repeated all that Tom Harris had told me when I went to ask for father; and I said how father had never been to the public before that night, and how mother had been to fetch him, though she was ill. Then he put out his kind hand, and lifted me up.

"'I am glad I heard you as I passed,' he said. 'Harris has been deceiving you, Ned. You might have guessed that, because he is so fond of frightening you, and has a grudge against your father. But this amounts to wickedness, and he shall be punished. I guess how it is, my lad. Your father is in the shed in the far meadow with the sick cow. I dare say he couldn't send a message from there, and has all the while expected he would be able to come home in a few more minutes. You may be sure he is as anxious to come as you are to see him, but he never neglects a sick animal. Dry your eyes, my lad, for the cottage is your home still, and it doesn't look at all "ruined," I think. Now build up the fire, and wait for your mother. I'll see about your father.'

"Oh, Jim, can you fancy what it was like then? I put my head into the cradle, and smothered baby with kisses; I made the fire up, and put on the kettle. Then I ran a little way down the dark road, calling out to mother, 'Make haste, mother! make haste!' At last she came, Jim—not white and crying and alone, as she had gone, not silent and sorrowful with father, like in my dream, but talking happily with him. And then how I longed that I could have given back my dead birds to their mother—given them back their home, as ours had been given to us! I don't know what I did for a bit, but when I'd got father and mother to have some tea, I laid my head down upon the cold nest, and while I held so tenderly the little dead birds—killed by these hands of mine, while the master who was kind to the birds had been so kind to me—I asked God to forgive me, and I made a promise to Him that He has let me be able to keep, for I ask Him again every night and every morning. Don't you think it's true, Jim, what mother says, that the more we love the things He loves, the more we love Him? That's all. It's quite ten minutes, isn't it? Are you going to take your nest again?"

"You might have told a cheerfuler tale, Ned. Tell another. There's no hurry about taking that nest again just yet."

The studios were open, all the artists had united,

And to see the very pretty show were lots of folks invited;

They came quite early in the day, they came till late at night,

And used up all the adjectives in showing their delight.

A water-color artist, rather grander than the rest,

Had a funny little usher in a funny costume dressed,

Who met the people at the door, and marshalled them the way

To where the easels were arranged with pictures for display.

And then he bowed a funny bow that made the people smile,

And through his funny little eyes he gazed at them the while,

As if to say, "My master is, you see, a clever man,

And on this grand reception day I do the best I can."

When the pictures were admired, and the people turned about,

This funny little usher would with grace escort them out,

And stand within the passage at a distance about right,

So as not to be familiar, but exceedingly polite.

There are many of the pictures that I can not now recall;

And the little living tableau I remember best of all

Was the funny little usher from the distant Isle of Skye,

Who did his duty well, and answered to the name of Fly.

The queer-looking figure in the accompanying etching is that of a halberdier, or one of a style of soldier that formed an important body of the European armies of four hundred years ago. We of to-day would laugh at soldiers in such queer costumes; but in those days the halberdiers were considered a very fine-looking and handsomely uniformed body of men. The halberd, or half battle-axe, was a stout shaft of wood some six feet in length, and having a curious steel head formed for cutting, thrusting, or tearing; that is, one side of it was shaped like a battle-axe, and was for cutting; the end was like a spear; and on the other side was a strong hook, which was very useful in tearing down outworks.

The halberd was used by the Scandinavians and the semi-barbarous tribes of Germany in the very earliest times. The Swiss introduced it into France in the fifteenth century, and it was first used in England in the time of Henry VIII.

In our day halberds are very seldom seen, and but few exist outside of museums, where they are preserved as curiosities. Until late in the last century they were used by certain court officials in England, and at the present time they are sometimes borne on occasions of state ceremony by the yeomen of the Queen's Guard.

During this walk Toby learned many things that were of importance to him, so far as his plan for running away was concerned. In the first place, he learned from the railroad posters that were stuck up in the hotel to which they went that he could buy a ticket for Guilford for seven dollars, and also that by going back to the town from which they had just come, he could go to Guilford by steamer for five dollars.

By returning to this last town—and Toby calculated that the fare on the stage back there could not be more than a dollar—he would have ten dollars left, and that surely ought to be sufficient to buy food enough for two days for the most hungry boy that ever lived.

When they returned to the circus grounds, the performance was over, and Mr. Lord in the midst of the brisk trade which he usually had after the afternoon performance, and yet, so far from scolding Toby for going away, he actually smiled and bowed at him as he saw him go by with Ben.

"See there, Toby," said the old driver to the boy, as he gave him a vigorous poke in the ribs, and then went off into one of his dreadful laughing spells—"see what it is to be a performer, an' not workin' for such an old fossil as Job is. He'll be so sweet to you now that sugar won't melt in his mouth, an' there's no chance of his ever attemptin' to whip you again."

Toby made no reply, for he was too busily engaged thinking of something which had just come into his mind to know that his friend had spoken.

But as old Ben hardly knew whether the boy had answered him or not, owing to his being obliged to struggle with his breath lest he should lose it in the second laughing spell that attacked him, the boy's thoughtfulness was not particularly noticed.

Toby walked around the show grounds for a little while with his old friend, and then the two went to supper, where Toby performed quite as great wonders in the way of eating as he had in the afternoon by riding.

As soon as the supper was over, he quietly slipped away from old Ben, and at once paid a visit to Mr. and Mrs. Treat, whom he found cozily engaged with their supper behind the screen.

They welcomed Toby most cordially, and despite his assertions that he had just finished a very hearty meal, the fat lady made him sit down to the box which served as table, and insisted on his trying some of her doughnuts.

Under all these pressing attentions, it was some time before Toby found a chance to say that which he had come to say, and when he did he was almost at a loss how to proceed; but at last he commenced by starting abruptly on his subject with the words, "I've made up my mind to leave to-night."

"Leave to-night?" repeated the skeleton, inquiringly, not for a moment believing that Toby could think of running away after the brilliant success he had just made. "What do you mean, Toby?"

"Why, you know that I've been wantin' to get away from the circus," said Toby, a little impatient that his friend should be so wonderfully stupid, "an' I think that I'll have as good a chance now as ever I shall, so I'm goin' to try it."

"Bless us!" exclaimed the fat lady, in a gasping way. "You don't mean to say that you're goin' off just when you've started in the business so well? I thought you'd want to stay after you'd been so well received this afternoon."

"No," said Toby, and one quick little sob popped right up from his heart, and out before he was aware of it; "I learned to ride because I had to, but I never give up runnin' away. I must see Uncle Dan'l, an' tell him how sorry I am for what I did; an' if he won't have anything to say to me, then I'll come back; but if he'll let me, I'll stay there, an' I'll be so good that by-'n'-by he'll forget that I run off an' left him without sayin' a word."

There was such a touch of sorrow in his tones, so much pathos in his way of speaking, that good Mrs. Treat's heart was touched at once; and putting her arms around the little fellow, as if to shield him from some harm, she said, tenderly: "And so you shall go, Toby, my boy; but if you ever want a home or anybody to love you, come right here to us, and you'll never be sorry. So long as Sam keeps thin and I fat enough to draw the public, you never need say that you're homeless, for nothing would please us better than to have you come to live with us."

For reply, Toby raised his head and kissed her on the cheek, a proceeding which caused her to squeeze him harder than ever.

During this conversation the skeleton had remained very thoughtful. After a moment or two he got up from his seat, went outside the tent, and presently returned with a quantity of silver ten-cent pieces in his hand.

"Here, Toby," he said, and it was to be seen that he was really too much affected even to attempt one of his speeches; "it's right that you should go, for I've known what it is to feel just as you do. What Lilly said about your having a home with us, I say, an' here's five dollars that I want you to take to help you along."

At first Toby stoutly refused to take the money; but they both insisted to such a degree that he was actually forced to, and then he stood up to go.

"I'm goin' to try to slip off after Job packs up the outside booth if I can," he said, "an' it was to say good-by that I come around here."

Again Mrs. Treat took the boy in her arms, as if it were one of her own children who was leaving her, and as she stroked his hair back from his forehead, she said: "Don't forget us, Toby, even if you never do see us again; try an' remember how much we cared for you, an' how much comfort you're taking away from us when you go; for it was a comfort to see you around, even if you wasn't with us very much. Don't forget us, Toby, an' if you ever get the chance, come an' see us. Good-by, Toby, good-by," and the kind-hearted woman kissed him again and again, and then turned her back resolutely upon him, lest it should be bad luck to him if she should see him after saying good-by.

The skeleton's parting was not quite so demonstrative. He clasped Toby's hand with one set of his fleshless fingers, while with the other he wiped one or two suspicious-looking drops of moisture from his eyes, as he said: "I hope you'll get along all right, my boy, and I believe you will. You will get home to Uncle Daniel, and be happier than ever, for now you know what it is to be entirely without a home. Be a good boy, mind your uncle, go to school, and one of these days you'll make a good man. Good-by, my boy."

The tears were now streaming down Toby's face very rapidly; he had not known, in his anxiety to get home, how very much he cared for this strangely assorted couple, and now it made him feel very miserable and wretched that he was going to leave them. He tried to say something more, but the tears choked his utterance, and he left the tent quickly to prevent himself from breaking down entirely.

In order that his grief might not be noticed, and the cause of it suspected, Toby went out behind the tent, and sitting there on a stone, he gave way to the tears which he could no longer control.

While he was thus engaged, heeding nothing which passed around him, he was startled by a cheery voice, which cried: "Hello! down in the dumps again? What is the matter now, my bold equestrian?"

Looking up, he saw Ben standing before him, and he wiped his eyes hastily, for here was another from whom he must part, and to whom a good-by must be spoken.

Looking around to make sure that no one was within hearing, he went up very close to the old driver, and said, in almost a whisper, "I was feelin' bad 'cause I just come from Mr. and Mrs. Treat, an' I've been sayin' good-by to them. I'm goin' to run away to-night."

Ben looked at him for a moment, as if he doubted whether the boy knew exactly what he was talking about, and then he said, "So you still want to go home, do you?"

"Oh yes, Ben, so much," was the reply, in a tone which expressed how dear to him was the thought of being in his old home once more.

"All right, my boy; I won't say one word agin it, though it do seem too bad, after you've turned out to be such a good rider," said the old man, thoughtfully. "It's better for you, I know; for a circus hain't no place for a boy, even if he wants to stay, an' I can't say but I'm glad you're still determined to go."

Toby felt relieved at the tone of this leave-taking. He had feared that old Ben, who thought a circus-rider was almost on the topmost round of fortune's ladder, would have urged him to stay, since he had made his début in the ring, and he was almost afraid that he might take some steps to prevent his going.

"I wanted to say good-by now," said Toby, in a choking voice, "'cause perhaps I sha'n't see you again."

"Good-by, my boy," said Ben, as he took the boy's hand in his. "Don't forget this experience you've had in runnin' away, an' if ever the time comes that you feel as if you wanted to know that you had a friend, think of old Ben, an' remember that his heart beats just as warm for you as if he was your father. Good-by, my boy, good-by, an' may the good God bless you!"

"Good-by, Ben," said Toby; and then, as the old driver turned and walked away, wiping something from his eye with the cuff of his sleeve, Toby gave full vent to his tears, and wondered why it was that he was such a miserable little wretch.

There was one more good-by to be said, and that Toby dreaded more than all the others. It was to Ella. He knew that she would feel badly to have him go, because she liked to ride the act with him that gave them such applause, and he felt certain that she would urge him to stay.

Just then the thought of another of his friends, one who had not yet been warned of what very important matter was to occur, came into his mind, and he hastened toward the old monkey's cage. His pet was busily engaged in playing with some of the younger members of his family, and for some moments could not be induced to come to the bars of the cage.

At last, however, Toby did succeed in coaxing him forward, and then, taking him by the paw, and drawing him as near as possible, Toby whispered: "We're goin' to run away to-night, Mr. Stubbs, an' I want you to be all ready to go the minute I come for you."

The old monkey winked both eyes violently, and then showed his teeth to such an extent that Toby thought he was laughing at the prospect, and he said, a little severely: "If you had as many friends as I have got in this circus, you wouldn't laugh when you was goin' to leave them. Of course I've got to go, an' I want to go; but it makes me feel bad to leave the skeleton, an' the fat woman, an' old Ben, an' little Ella. But I mustn't stand here. You be ready when I come for you, an' by mornin' we'll be so far off that Mr. Lord nor Mr. Castle can't catch us."

The old monkey went toward his companions, as if he were in high glee at the trip before him, and Toby went into the dressing tent to prepare for the evening's performance, which was about to commence.

It appeared to the boy as if every one was unusually kind to him that night, and feeling sad at leaving those in the circus who had befriended him, Toby was unusually attentive to every one around him. He ran on some trifling errand for one, helped another in his dressing, and in a dozen kind ways seemed as if trying to atone for leaving them secretly.

When the time came for him to go into the ring, and he met Ella, bright and happy at the thought of riding with him, and repeating her triumphs of the afternoon, nothing save the thought of how wicked he had been to run away from good old Uncle Daniel, and a desire to right that wrong in some way, prevented him from giving up his plan of going back.

The little girl observed his sadness, and she whispered, "Has any one been whipping you, Toby?"

Toby shook his head. He had thought that he would tell her what he was about to do just before they went into the ring, but her kind words seemed to make that impossible, and he had said nothing when the blare of the trumpets, the noisy demonstrations of the audience, and the announcement of the clown that the wonderful children riders were now about to appear, ushered them into the ring.

If Toby had performed well in the afternoon, he accomplished wonders on this evening, and they were called back into the ring, not once, but twice; and when finally they were allowed to retire, every one behind the curtain overwhelmed them with praise.

Ella was so profuse with her kind words, her admiration for what Toby had done, and so delighted at the idea that they were to ride together, that even then the boy could not tell her what he was going to do, but went into his dressing-room, resolving that he would tell her all when they both had finished dressing.

Toby made as small a parcel as possible of the costume which Mr. and Mrs. Treat had given him—for he determined that he would take it with him—and putting it under his coat, went out to wait for Ella. As she did not come out as soon as he expected, he asked some one to tell her that he wanted to see her, and he thought to himself that, when she did come, she would be in a hurry, and could not stop long enough to make any very lengthy objections to his leaving.

But she did not come at all; her mother sent out word that Toby could not see her until after the performance was over, owing to the fact that it was now nearly time for her to go into the ring, and she was not dressed as yet.

Toby was terribly disappointed. He knew that it would not be safe for him to wait until the close of the performance if he were intending to run away that night, and he felt that he could not go until he had said a few last words to her.

He was in a great perplexity, until the thought came to him that he could write a good-by to her, and by this means any unpleasant discussion would be avoided.

After some little difficulty he procured a small piece of not very clean paper, and a very short bit of lead-pencil, and using the top of one of the wagons, as he sat on the seat, for a desk, he indited the following epistle:

"deaR ella I Am goin to Run away two night, & i want two say good by to yu &, your mother. i am Small & unkle Danil says i dont mount two much, but i am old enuf two know that you have bin good two me, & when i Am a man i will buy you a whole cirkus, and we Will ride together, dont forgit me & I wont yu in haste

"Toby Tyler."

Toby had no envelope in which to seal this precious letter, but he felt that it would not be seen by prying eyes, and would safely reach its destination, if he intrusted it to old Ben.

It did not take him many moments to find the old driver, and he said, as he handed him the letter, "I didn't see Ella to tell her I was goin', so I wrote this letter, an' I want to know if you will give it to her."

"Of course I will. But see here, Toby"—and Ben caught him by the sleeve, and led him aside where he would not be overheard—"have you got money enough to take you home? for if you haven't, I can let you have some," and Ben plunged his hand into his capacious pocket as if he was about to withdraw from there the entire United States Treasury.

Toby assured him that he had sufficient for all his wants; but the old man would not be satisfied until he had seen for himself, and then taking Toby's hand again, he said: "Now, my boy, it won't do for you to stay around here any longer. Buy something to eat before you start, an' go into the woods for a day or two before you take the train or steamboat. You're too big a prize for Job or Castle to let you go without a word, an' they'll try their level best to find you. Be careful, now, for if they should catch you, good-by any more chances to get away. There"—and here Ben suddenly lifted him high from the ground, and kissed him—"now get away as fast as you can."

Toby pressed the old man's hand affectionately, and then, without trusting himself to speak, walked swiftly out toward the entrance.

He resolved to take Ben's advice, and go into the woods for a short time, and therefore he must buy some provisions before he started.

As he passed the monkeys' cage he saw his pet sitting near the bars, and he stopped long enough to whisper, "I'll be back in ten minutes, Mr. Stubbs, an' you be all ready then."

Then he went on, and just as he got near the entrance, one of the men told him that Mrs. Treat wished to see him.

Toby could hardly afford to spare the time just then, but he would probably have obeyed the summons if he had known that by so doing he would be caught, and he ran as fast as his little legs would carry him toward the skeleton's tent.

The exhibition was open, and both the skeleton and his wife were on the platform when Toby entered, but he crept around at the back, and up behind Mrs. Treat's chair, telling her as he did so that he had just received her message, and that he must hurry right back, for every moment was important then to him.

"I put up a nice lunch for you," she said, as she kissed him, "and you'll find it on the top of the biggest trunk. Now go; and if my wishes are of any good to you, you will get to your uncle Daniel's house without any trouble. Good-by again, little one."

THE RUNAWAYS.

THE RUNAWAYS.

Toby did not dare to trust himself any longer where every one was so kind to him. He slipped down from the platform as quickly as possible, found the bundle—and a good-sized one it was, too—without any difficulty, and went back to the monkeys' cage.

As orders had been given by the proprietor of the circus that the boy should do as he had a mind to with the monkey, he called Mr. Stubbs, and as he was in the custom of taking him with him at night, no one thought that it was anything strange that he should take him from the cage now.

Mr. Lord or Mr. Castle might possibly have thought it queer had either of them seen the two bundles which Toby carried, but fortunately for the boy's scheme, they both believed that he was in the dressing tent, and consequently thought that he was perfectly safe.

Toby's hand shook so that he could hardly undo the fastening of the cage, and when he attempted to call the monkey to him, his voice sounded so strange and husky that it startled him.

The old monkey seemed to prefer sleeping with Toby rather than with those of his kind in the cage, and as the boy took him with him almost every night, he came on this particular occasion as soon as Toby called, regardless of the strange sound of his master's voice.

With his bundles under his arm, and the monkey on his shoulder, with both paws tightly clasped around his neck, Toby made his way out of the tent with beating heart and bated breath.

Neither Mr. Lord, Castle, nor Jacobs were in sight, and everything seemed favorable for his flight. During the afternoon he had carefully noted the direction of the woods, and he started swiftly toward them now, stopping only long enough, as he was well clear of the tents, to say, in a whisper:

"Good-by, Mr. Treat, an' Mrs. Treat, an' Ella, an' Ben. Some time, when I'm a man, I'll come back, an' bring you lots of nice things, an' I'll never forget you—never. When I have a chance to be good to some little boy that felt as bad as I did, I'll do it, an' tell him that it was you did it. Good-by."

Then turning around, he ran toward the woods as swiftly as if his escape had been discovered, and the entire company were in pursuit.

A mist of green on the willows;

A flash of blue 'mid the rain;

And the brisk wind pipes,

And the brooklet stripes

With silver hill and plain.

Hark! the bluebirds, the bluebirds

Have come to us again!

The snow-drop peeps to the sunlight

Where last year's leaves have lain;

And a fluted song

Tells the heart, "Be strong:

The darkest days will wane.

And the bluebirds, the bluebirds

Will always come again!"

Berlin, March, 1881.

It will be long after Christmas before you get this letter, dearest Clytie, but, for all that, I'm sure you will like to hear about my German holidays. If my letter seems mixed up and secure, you must excuse it, for my mind is in a perfect whirligig. One of their festivals, or "Fest-tag," as they say here, is so different from any we have at home, that I must tell you about it, although it happened so many weeks ago. It is "Nicholas-day," and comes on the 6th of December. My new cousins Ilsie and Lisbet told me that St. Nicholas always comes himself, and leaves presents at every house for the good children, and a bunch of rods for the naughty ones. He lives ever so far away, and is a kind of relation of Santa Claus—second cousins or step-fathers, maybe. Some people say he was once a real man, and lived in Asiaminer, wherever that may be; that he was a great Bishop there, and was so good to little children that they called him "dear Father Nicholas," and when he died they called him "Saint," and kept his birthday by giving presents to everybody. Well, that evening we had quite a party in mamma's parlor: all our cousins, besides Minna and Karl, Randolph and Helen, Cousin Carrie and two or three of mamma's friends. Cousin Frank didn't come till after St. Nicholas had gone—wasn't it too bad?

Well, we were talking and playing together, when all at once we heard a great shouting and stamping of feet, ringing of bells and blowing of horns; the door was thrown open, and in stalked St. Nicholas himself! He was as tall as a real giant; his beard came down below his knees; he wore great goggles, and carried a switch in his hand. He cried out in a terrible voice, "Where are the bad children?"

Then papa said, "Dear St. Nicholas, we have no bad children here; they are all as good as good can be."

At that St. Nicholas laughed, and he kept laughing louder and louder. He hid the switch under his cloak, and said: "Somehow I can't find any naughty children anywhere. What a beautiful world it is, to be sure—a world full of good boys and girls!"

Then he opened a bag and shook out nuts, raisins, apples, and oranges, and while we were scrambling for them, he hurried away, before we could say, "Thank you."

Next came Christmas, which I can't write about now, and then Twelfth-night, when we had a splendid supper, with a great plum-cake in the middle of the table, covered all over with queer little sugar things, cats and dogs and rabbits, chocolate shoes and mice and goats, and cunning little candy babies.

Do you wonder that I have had no time for writing you lately, and that my mind should be in a whirligig, and my thoughts go higgledy-piggledy? for besides all this, we went to Leipsic to the New-Year's fair. The fair is held out-doors, and people come from all parts of the world, bringing curious things to sell. They have their booths in the public squares, and it is merry and noisy from morning till night. There are Spaniards and French and Swiss and Italians, and just such people as I've read you about in my Stories of all Nations, and they look exactly like the pictures I've shown you so often. The fair lasts a fortnight, and at the end of it is Carnival. Then there are bands of music everywhere, and processions march through all the streets, and oh, dear me, Clytie! I can't give you a nidea of the funny times we had.

The doll I have in my lap I bought at the fair, and have named her Princess Carnival. She is a magnificent creature, and I admire and suspect her; but as for loving her—there is no doll in the world to compare with you, my Clytie, when it comes to loving. You are not as handsome as Princess Carnival, but I love you a million times more, my pet, than I can ever love her, beautiful as she is.

And now good-night. Be as happy as you can, and take good care of the others, till I come back to you all.

THE MAGIC LANTERN.—Drawn by S. G. McCutcheon.

THE MAGIC LANTERN.—Drawn by S. G. McCutcheon.

The picture on the next page represents one of the most remarkable incidents in the life of Dr. Samuel Johnson. This famous man prided himself upon being odd and different from other men, and in doing queer things that no one else would have thought of doing; and the picture shows him in the act of carrying out one of the queer ideas for which he was noted.

Dr. Johnson's father was a bookseller in a small way, and was in the habit of setting up stalls or booths for the sale of books in the market-places of towns in the neighborhood of Lichfield, where he lived, on market-days. Sometimes he took his son Samuel with him as an assistant. This son Samuel, who afterward became Dr. Johnson, said, in speaking of the incident to which the picture refers, that as a general thing he could not accuse himself of having been a disobedient child. "Once, indeed," said he, "I was disobedient: I refused to attend my father to Uttoxeter market. Pride was the source of that refusal, and the remembrance of it was painful. A few years ago I desired to atone for this fault. I went to Uttoxeter in very bad weather, and stood for a considerable time, bare-headed, in the rain, on the spot where my father's stall used to stand."

So here the wise Doctor is, standing bare-headed in the open market-place, exposed to drenching rain, and to the jeers of the people. And all this, when he is more than seventy years of age, for the purpose of trying to atone for one act of disobedience committed in his boyhood!

This quaint method of doing penance for an act that most men would have forgotten long before is but a specimen of his innumerable queer actions. These were so novel and so original as to gain for him the name of "Oddity," by which he was very generally known.

DR. JOHNSON IN UTTOXETER MARKET-PLACE.—See Preceding Page.

DR. JOHNSON IN UTTOXETER MARKET-PLACE.—See Preceding Page.

If our heroine, Cynthia Smith, walked the earth to-day, she would be a great-great-grandmother. But at the time of this story, 1780, she was only a small girl, who lived on a plantation near the Santee River, in South Carolina. She was twelve years old, four feet and two inches high, and, for so young and so small a person, she was as stanch a rebel as you could have found in all America; for the War of Independence had been raging in the United States ever since Cynthia could remember.

When she was only five years old, her little heart had beaten hard at the story of the famous "Boston Tea Party," at which a whole ship-load of tea had been emptied into the harbor because stupid George III. insisted on "a threepenny tax."

"And New York and Philadelphia would 'a done the same, but for the ships turning tail, and going where they came from. They've burned the stuff in Annapolis, and it's spoiling in the Charleston cellars, bless the Lord!" said Mr. Smith, striking his heavy hand on his knee.

"Hurray!" shouted John and Jack and William and Ebenezer, Cynthia's brothers. "Hurray!" echoed Cynthia, as if she understood all about it.

The following year, when England shut up Boston Harbor with her "Stamp Act," never a bit of rice did Cynthia get to eat, for her father sent his whole harvest North, as did many another Southerner.

After that, John went to Massachusetts to visit Uncle Hezekiah, and the next June they heard that he had been shot dead at the battle of Bunker Hill.

Cynthia wept hot tears on her coarse homespun apron; but she dried them in a sort of strange delight when Jack, all on fire to take John's place, insisted on joining the Virginia Riflemen, and following a certain George Washington to the war.

"It's 'Liberty or Death' we have marked on our shirts, and it's 'Liberty or Death' we have burned into our hearts," Jack wrote home; at which his mother wrung her hands, and his father smiled grimly.

"Just wait, you two other boys," said the latter; "we'll have it hot and heavy at our own doors before we're through."

That was because Will and Ebenezer wished to follow in Jack's footsteps. Cynthia longed to be a boy, that she might indulge in a private skirmish with the "Britishers" on her own account.

But she had little time for even patriotic dreamings and yearnings. There was a deal of work to be done in those days.

Cynthia helped to weave cloth for the family gowns and trousers, and to spin and knit yarn for the paternal and fraternal stockings. This kept her very busy until 1776, when two great events took place.

One was the signing of the Declaration of Independence; the other was the birth of a red and white calf in Mr. Smith's barn. Which was of the most importance to Cynthia it is hard to say.

To be sure, she tingled from head to foot at her father's ringing tones, as he read from a sheet of paper some one had given him, "All men are born free and equal"; but she also went wild with joy when her father said, "You may keep that bossy for your own, if you'll agree to raise her, Cynthy."

Cynthia took the calf into her inmost heart, and she named her "Free-'n'-equal." That was the way the words sounded to her.

If ever an animal deserved such a name, this was the beastie. She scorned all authority, kicked up her hind-legs, and went careering round the plantation at her own sweet will, only coming to the barn when Cynthia's call was heard.

Free-'n'-equal was Cynthia's only playmate, for no children lived within six miles. As the calf grew into a cow, the more intimate and loving were the two. To Free-'n'-equal did Cynthia confide all her secrets, and chiefly did she inform her of her sentiments in regard to the war. She even consulted her as to the number of stitches to be put on a pair of wristlets for Jack, who in this winter of 1777-78 had gone with General Washington to Pennsylvania. Alas! Jack never wore those wristlets. He was one of the many who lay down to die of cold and hunger in that awful Valley Forge. Cynthia believed that Free-'n'-equal understood all the sorrow of her heart when she told her the pitiful news.

Quite as much did she share her joy when Cynthia came flying to the barn with the joyful tidings that British Burgoyne had surrendered at Saratoga.

Again the joy vanished, and Cynthia sobbed her woe into Free-'n'-equal's sympathizing ear when Sir Henry Clinton captured Charleston, only twenty miles away.

But she sobbed even more a few months later.

"For General Gates has come down to South Carolina, Free-'n'-equal, and father and Will and Ebenezer have gone to fight in his army."

Free-'n'-equal shook her head solemnly at that, and her long low "Moo-o" said, plainly enough, "What's to become of the rest of us, my poor little mistress?"

Cynthia brushed away her tears in a twinkling.

"We'll take care of ourselves, that's what we'll do. Mother and I'll hoe the rice. And, Free-'n'-equal, you've got to toe the mark, and give more milk than ever to keep us strong and well."

"Trust me for that," said Free-'n'-equal's eyes.

And she kept her promise. Rich yellow milk did she give, pailful after pailful. Cynthia and her mother worked like men, and fed on the cream.

Those were dangerous days all along the Santee River, for Lord Cornwallis's troops were roaming over the land, and laying waste the country. But Cynthia was not afraid—no, not even when Lord Cornwallis came within three miles of the plantation. She said her prayers every day, and believed firmly in the guardian angels, and a certain rusty gun behind the kitchen door.

"Just let those soldiers touch anything of ours, and see what they'll get!" said she, with ponderous dignity.

Free-'n'-equal was perfectly sure Cynthia could manage the whole British army, if need were, and munched her cud in blissful serenity.

Oh no, Cynthia had no fear, even when a red-coat did sometimes rise above the horizon like a morning cloud. She regarded him no more than she would a scarlet-breasted bird which sung above her head when she went into the forest hard by to gather sticks.

So no wonder that she was taken mightily aback when, one afternoon as she came home with her bundle of sticks, her mother met her with wide-open eyes and a pale face.

"Cynthy, they've been here and carried off Free-n'-equal."

"'They!'" gasped Cynthia. "Who?"

"The British soldiers. They tied a rope round her horns. She kicked well, but they jerked her along. Cynthy, Cynthy, what shall we do?"

Cynthia uttered a sound between a groan and a war-whoop, and darted out of the door. Along the dusty road she ran, on and on. Her yellow sun-bonnet fell back on her shoulders, and her brown curls were covered with dust. One mile, two miles, three miles—on and on. At last she reached a small house, which was Lord Cornwallis's head-quarters. Never a moment did Cynthia pause. The sentinels challenged her in vain. She marched majestically past them. Into the house—into the parlor—walked she.

There sat Lord Cornwallis and some six of his officers, eating and drinking at a big table.

Cynthia stopped at the threshold and dropped a courtesy.

Lord Cornwallis glanced up and saw her.

Miss Cynthia dropped another courtesy, opened her lips, and spake.

"I am Cynthia Smith," said she, gravely, "and your men have taken my cow, Free-'n'-equal Smith, and I've come to fetch her home, if you please."

"Your cow?" questioned Lord Cornwallis, pausing, with a wine-glass in his hand.

"They carried her off by a rope," said Cynthia.

"Where do you live?" asked the British General.

"Three miles away, along with my mother."

"Have you no father?"

"One, and four brothers."

"Where is your father?"

"In General Gates's army, Mr. Lord Cornwallis."

"Oh, he's a rebel, is he?"

"Yes, sir," said Miss Cynthia, proudly erect.

"And where are your brothers?"

Cynthia paused. "John he went to heaven along with General Warren, from the top of Bunker Hill," said she, with a trembling lip.

One of the younger officers smiled, but he stopped in a hurry as Lord Cornwallis's eyes flashed at him.

"And Jack went to heaven," proceeded Cynthia, softly, "out of Valley Forge, where he was helping General Washington."

"Where are the other two?"

"In the army, Mr. Lord Cornwallis." Cynthia's head was erect again.

"Rank rebels."

"Yes, they are."

"Hum! And you're a bit of a rebel too, I'm thinking, if the truth were told."

Miss Cynthia nodded with emphasis.

"And yet you come here for your cow," said Lord Cornwallis. "I'll be bound she's rebel beef herself."

Cynthia meditated. "I think she would be if she had two less legs, and not quite so much horn. That is, she'd be rebel, but maybe they wouldn't call her beef then."

Lord Cornwallis threw back his head and laughed a good-natured, hearty laugh that made the room ring. All his officers laughed too, including the miserable red-coat who had smiled over John's fate.

Miss Cynthia wondered what the fun might be; but in no wise abashed, she stood firm on her two little feet, and waited until, the merriment over, they might see fit to return to the cow in hand, which was certainly worth any two in the camp.

At last her face began to flush a little. What if these fine gentlemen were making game of her, after all.

Lord Cornwallis saw the red blood mount in her cheeks, and just because he was a real gentleman, he became sober instantly. "Come here, my little maid," said he. "I myself will see to it that your cow—"

"Free-'n'-equal," suggested Cynthia.

"That Free-'n'-equal," repeated Lord Cornwallis, courteously, "is safe in your barn to-morrow morning. And perhaps," he added, unfastening a pair of silver knee-buckles which he wore, "you will accept these as a gift from one who certainly wishes no harm to these rebels. And that his Majesty himself knows."

Then he rose and held his wine-glass above his head; so did every officer in the room.

"Here's to the health of as fair a little rebel as we shall meet, and God bless her!" said he.

She dropped her final courtesy, clasped the shining buckles, and out of the room she vanished, sure in her mind that Free-'n'-equal was all her own once more.

As for those buckles, children dear, they are this very day in the hands of one of Cynthia's descendants. For there was a real cow and a real Miss Cynthia, as well as a real Lord Cornwallis.

It was a perfect morning. Blue sky, with pure little snow-drop clouds, as if the angels had dropped them from their baskets as they tended the flowers in the heavenly gardens. The lake sparkled and glistened in the sunshine, and every wave seemed to leap joyously as it broke in soft foam on the shore. In one end of the Flyaway sat Phil, on a pile of shawls; in the other were stowed a large basket, a pail of ice, and a pail of milk, and in between were Miss Rachel, Lisa, Joe, and Graham. Phil had twisted up a little nosegay for each, and had pinned a broad wreath of grape leaves around Joe's straw hat, making the old fellow laugh at his nonsense. They were just pushing off, when a sudden rattling of chain and some impatient barks from Nep showed that he began to feel neglected.

"I thought we could get away unnoticed," said Miss Rachel, "but I find myself mistaken."

The boys pleaded for Nep. "Ah, let him come, please let him come."

Nep's leaps becoming frantic, Miss Rachel yielded, and Graham soon had him loosened. He jumped at once into the boat, and crept under Phil's feet, making a nice warm mat.

"Poor Nep," said Phil, patting him, "he felt neglected;" and the big tail wagged thankful thumps against the boat.

The morning air was sweet with all manner of herbage yet fresh from the morning dew. The trees were in their most brilliant green, and every leaf seemed newly washed.

Graham began a boating song, and Miss Schuyler joined in the chorus. Old Joe chuckled and grinned; even quiet Lisa hummed a little as the song rose louder; and Phil, dipping his hands in the clear water, imagined that the fishes were frisking a waltz in their honor. They glided past Point of Rocks, past huge beds of water-lilies, past lovely little coves and inlets, and spots where Graham said there was excellent fishing; finally Eagle Island became more distinct, and its pine-trees began to look imposing.

"Here we are!" said Graham at last, bringing the Flyaway up nicely on a pebbly beach, in good boating style.

Graham and Joe made a chair with their hands and arms, and so carried Phil very comfortably to the place under the trees which Miss Rachel had chosen for their encampment.

"Now," said Miss Rachel, as she brought out Phil's portfolio, a book, her own embroidery, and Lisa's sewing, "I propose that Graham, being a more active member of society than we are, go off with Joe and catch some fish for our dinner."

"Just the thing!" said Graham; "but I did not bring a line."

"Joe has everything necessary, bait and all," said Miss Schuyler.

"Now," said Miss Rachel, when the fishermen had gone, seeing Phil's longing look, and knowing well how much he would have liked to go with them, "we must go to work too, so that we may enjoy our play all the more afterward. I could not let you go with Graham, my dear Phil; it would have fatigued you too much; but I want you to try and draw me that drooping bush on the edge of the water, and while you draw I will read aloud for a while."

Miss Schuyler read, explained, talked to Phil about his drawing, and gave him the names of the trees about him.

The time flew fast, and it seemed a very little while[Pg 364] when Miss Schuyler said to Lisa, "I think I hear oars; we had better be getting our feast ready."

They brought out the basket and pails, spread a nice red dessert cloth down on a smooth patch of grass, laid broad green leaves down for the rolls and biscuits; golden balls of butter were in a silver dish of their own, and so were the berries in a willow basket, around which they put a few late wild flowers.

"Now we want a good flat stone for our fire-place, and— Ah! here come our fishermen just in time."

Graham and Joe now appeared with a few perch, but plenty of cat-fish. They went to work with zeal, and soon had enough brush for the fire, which they built at a good distance. And whilst Graham fed it, Joe skinned his cat-fish, salted the perch, and laid them on the stone.

Then they all sat around their grassy table, and Joe served them in fine style, bringing them their fish smoking hot on white napkins.

How merry they were over the good things, and how eager Graham was to cook fish for Joe, and serve the old fellow as nicely as he had done all of them! And Phil cut the very largest slice of cake for Joe.

"It is just the jolliest picnic I ever was at," said Graham, helping to wash and clear away, and re-stow spoons and forks.

"Of course it is," said Phil. "There never can be another quite so nice: it is my first one, you know."

"Yes; just think of it, and it's my fiftieth, I suppose; but then you must not think all picnics like this. It is something really remarkable to have everything go off so smoothly. Why, sometimes all the crockery gets smashed, or the fire won't burn, or if it does, you get the smoke in your eyes, or your potatoes get burned, and your lemonade gets in your milk, or somebody puts your ice in the sun, and, to crown all, down comes a shower."

"Dear! dear! what a chapter of accidents, Graham!"

"Are you listening, Miss Rachel?" said Graham, with a quizzical look. "I was only letting Phil know how much better you manage than most people."

"Well, when you and Phil are ready, I want to tell you about something else I should like to manage. Come, put away all the books and work, and listen to my preaching."

Miss Rachel sat on a fallen tree, leaning against some young birches. "Phil was asking me, yesterday," said she, "what became of all the poor sick children in the city, and he seemed to think he ought in some way to help them. So I promised him to think about what he had been considering, and a little plan came into my head in which I thought you could help us, Graham."

Graham looked up with a pleased face, and nodded.

"It is just this. In the city hospitals are many sick children who have to stay in bed almost all the time. Now Phil and I want to do the little that we can for them, and it seems to me it would be nice to send fresh flowers and fruit—all that we can spare from our gardens—once or twice a week to some of these sick city children. What do you think, boys?"

"It would be lovely, Miss Schuyler," said Phil, "only I do not see how we could help; it would all come from you."

"Not all, dear child. I mean to give you both a share of the work—you in your way, and Graham in his. Are you interested? Shall I go on and tell you?"

"Yes, indeed," both exclaimed.

"I propose that we set aside a certain part of our flower garden and our fruit trees, you and I, Graham (for I know you have a garden of your own), which we will call our 'hospital fruits and flowers,' and Phil is to assist in making up bouquets, hulling berries, and packing to send away; besides that, he is to make some little pictures, just little bits of sketches of anything that he fancies—a spray of buds, a single pansy, Joe's old hat and good-natured face beneath, a fish, or a bit of vine-covered fence—and we will sell them for him, and the money shall help pay the express charges upon our gifts to the sick children, so that Phil will really be doing more than any of us. How do you like my plan?"

"LOOK! THERE'S AN EAGLE."

"LOOK! THERE'S AN EAGLE."

The boys were pleased, and had begun to say so, when a shout came from the other part of the island, from Joe, and Nep set up a violent harking.

"Hi! look up dar, Miss Schuyler!" called out Joe.

"Quick, Phil!" said Graham; "look! there's an eagle. How fortunate we are! There he goes sailing away in all his glory;" and sure enough the great bird floated further and further up in the blue sky.

Still Nep kept on barking, and Graham ran down to see what was the matter. He came back with something dangling from his hand, Joe and Nep following.

"A black snake!—oh, what a dreadful creature!" exclaimed Lisa.

"Yes, indeed, ma'am," said Joe, "and if Nep hadn't barked so, the drefful cretur would have bitten me sure. That dog knows a heap; you'd better allus take him with you in the woods, Miss Rachel. I was lyin' off sound asleep, with this critter close beside me, when Nep come up, and barked just as plain as speakin'. 'Take care,' says he, 'ole Joe, you're in danger,' an' with that I woke in a hurry, an' jist then I saw that big eagle come soarin' overhead, and then Marsa Graham come and give that snake his death-blow."

"How did you do it, Graham?" asked Phil, excitedly.

"Oh, I pounded him on the head with a stone as he was making off. He is a pretty big fellow, and he must have swum from the mainland, Miss Schuyler."

"Yes, I never saw a snake on this island before."

"Come here, Nep," said Phil, "dear old fellow; good dog for taking care of Joe. Your head shall be my first picture for our sick children."

ne of the most exquisite pieces of embroidery I ever saw was brought from the Royal School of Art Needle-Work at South Kensington by a gentleman who imports the most beautiful art embroideries for sale in this country. This was a sofa pillow of soft yellow India silk, with the design outlined, and the rest of the surface darned back and forth in a rich old-gold-color. A few lines of pale pink veined the petals, and there was a narrow border of dull greenish-blue that inclosed the whole. The only stitch used was simply an irregular darning stitch. The work was so charming and so easy that any young girl would enjoy doing it. It would be a very pretty way of embroidering work-bags or squares for the backs of wall-brackets. The soft India silks are hard to find, but you may find a dull yellow Surah silk, and there is a soft cream-colored pongee that would do. Something near the color of a light yellow nasturtium would be best. Get a piece eight inches square, trace on it the design of Fig. 17, and back the silk with a piece of soft, very thin unbleached muslin, and overcast the edges. Fig. 17 is just the size of a tile such as is usually set in square wall-brackets. Buy a skein or two of old gold filoselle of a somewhat darker shade than your silk, or a good bronze-color that harmonizes well with it. First run the outline of your flowers in the dark yellow or bronze, and the shading lines, taking up but few threads of the silk with your needle, so that the outline will show strong and plain on the surface. Outline the leaves and stems in a dull, not too dark, green. Take two or three threads from a strand of filoselle in your needle at once, and do not take too long a needleful. Then darn the background back and forth, making the threads run parallel to each other, but with constant variation as to the length of stitch and the closeness of the lines—in this way:

The background could be darned in dull blue if you prefer, or with slightly varying shades of yellow. The irregularity in stitch, in closeness of the lines, and in shade, all help to give the work a very antique look. A narrow border can be darned all around of another color that will not contrast too sharply with the flowers or the background.

Fig. 17.

Fig. 17.

Villa Piscione, Posilippo, Naples, Italy.

In the month of January a party of Americans had the honor of a special excavation at Pompeii. There were nine in the party. We had a room given us to be excavated. They found some table legs of bronze ornamented with ivory rings, and a bronze vase which had stood on the same table; also some nails and pieces of terra-cotta vases. After the workmen had finished excavating, some of us went to digging. My sister found two nails, auntie and another lady found some nails too, and I found one handle of the bronze vase, which had been broken off. We also went to where the workmen were making the regular excavations, and saw a little bit of a fountain, which the manager said was the finest which had been found yet. It was of mosaic. Then we went to the Stabian Baths, and had our luncheon, which was spread on an old marble fountain—a dry one, of course. The Stabian Baths was the largest bathing establishment in Pompeii. It was called Thermæ.

We went upon an embankment, and took a bird's-eye view of Pompeii. It is a great mass of houses without roofs, and is a very odd sight. I have seen it several times, and it does not look very strange to me now.

I do not remember my first visit there, but I am told that I danced on one of the mosaic floors in the house of Sallust, and the guide said that children always wanted to dance in Pompeii. I would like to write more about this old buried city, but I must go to school.

I am nine years old, and my sister is eight. We are delighted with Young People, especially with the story of "Toby Tyler," and are impatient for the mail that brings it.

Odell H. D.

West Union, Ohio.

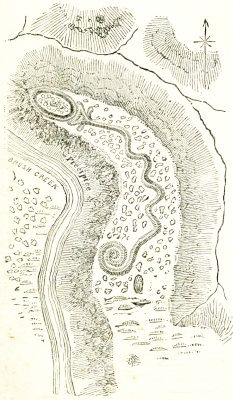

There is a very interesting Indian mound near this place, on the banks of Brush Creek. It is called the Serpent Mound, because it is in the form of a serpent. It is nearly one thousand feet in length, extending in graceful curves, and ending in a triple coil at the tail. Its neck is stretched out and slightly curved, and its mouth is opened wide, as if in the act of swallowing an oval figure, like a huge egg. Some think it was built to represent the Oriental idea of the serpent and the egg. It is said to have been the work of a race of men called the Mound-Builders, very many years ago. There are other mounds here, but none so interesting as this one.

Ettie C. I.

THE GREAT SERPENT MOUND.

THE GREAT SERPENT MOUND.

The mound described by our young correspondent is in Adams County, Ohio, and is one of a number called "animal mounds," because they represent the forms of animals, or birds, or men, instead of the usual type of the pyramid or circle. The Serpent Mound is described in Short's work on The North Americans of Antiquity, published by Harper & Brothers, from which we take the accompanying illustration. It lies "with its head conforming to the crest of hill, and its body winding back for seven hundred feet in graceful undulations." Another remarkable work by the ancient race of men is a large elephant mound, found a few miles below the mouth of the Wisconsin River. It is so perfect in its proportions that its builders must have been well acquainted with all the physical characteristics of the elephant; so that the mound-builders may have been of Asiatic origin, or lived when the great mastodon of North America roamed over the continent. Another mound, in Licking County, Ohio, represents an alligator. It is about two hundred feet in length, twenty feet broad, and each of the paws is twenty feet long.

Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.

I live near where the celebrated David Crockett once lived. His old house is still standing on our place. The logs are full of auger-holes, where I suppose he had wooden pins to support shelves, or to hang clothes and household things on. When my grandpa was a little boy he knew David Crockett very well.

Ella B.

David Crockett was a famous hunter, who was born in Tennessee in 1786. He was a political friend of General Jackson, and was several times elected to Congress. He was a great humorist, and very eccentric in his habits. When the people of Texas revolted against the government of Mexico, he enlisted in the Texan army, and lost his life in the terrible massacre at Fort Alamo, in 1836, when the Mexicans, in violation of the rules of war, slaughtered all their prisoners.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I am a little boy five years old. I take Harper's Young People, and mamma and auntie read me all the pretty stories and all the little letters in the Post-office Box.

I have a little brother three years old. We each have a bank in which we keep our pennies. George's bank is a great big cross-looking bull-dog. He has a flat place on his nose. If we put a penny on it, and then pull his tail, he will open his mouth and swallow the penny. My bank is a soldier who is standing in front of the trunk of a tree. He has a gun in his hand, with which he points at a hole in the tree. When I put a penny on the end of the gun, and touch the soldier's foot, he fires off the gun, and the penny goes into the hole. Papa gives us each a penny every day we are good; but every day we are naughty we have to give him one. I have fifty-one pennies in my bank. George has not quite so many, but I am the oldest, and I ought to be the best boy.

I would like to write about some of our playthings, but I am afraid my letter would be too long.

John I. McK.

New York City.

I would like to tell Young People what kind friends I have. I am a poor little girl, and my mamma has to go out to work. I go to the public school, but I am not very strong, and the noise and close air sometimes make me sick. Once I had to stay from school a long time; and there was a little girl who had a private teacher come every day, and she let me go and study with her. She used to pay my car fare out of her own spending money. It cost her sixty cents a week. And she made me a present of all my school-books, and a great many other handsome books. I do not think there are many little girls so kind.

There is another little girl who made me a Christmas present of Young People, and I will have it all the year. She, too, is very kind to me. I like Young People very much. I think "Mildred's Bargain," "Phil's 'Fairies," and especially poor "Toby Tyler," are splendid stories.

May H.

South Kirtland, Ohio.

I thought I would tell Young People about my pet sheep. My grandpa gave me a sheep and a lamb when I was a baby, and now I have seven. They are all very tame, and almost run over me when I feed them. I am seven years old.

I read in the Third Reader, and I study arithmetic and geography, but I have never been to school.

Frank T. C.

Berea, Ohio.

I live on a beautiful farm. My papa raises lots of onions, and sends them to Cincinnati by car-loads. There are a great many stone quarries in this place, where they make grindstones. They are sent all over the world from here. They also get big blocks of stone from the quarries for building railroad bridges, houses, and sidewalks.

Last summer I went up the lakes with papa and mamma as far as Marquette. We saw lots of Indians sailing down the rivers in their canoes, and a great many other pretty and interesting sights.

Mamie W.

St. Louis, Missouri.

When we lived in the country my sister had a pet deer. Its name was Nellie. It was a very pretty creature. When we were in the garden, and were hungry, we used to send Nellie to get us some bread, and the darling little thing would go and get a loaf of bread from grandma and bring it out to us. One day Nellie was running in the woods, and some one shot her. My sister cried very much, and we buried poor Nellie, and put flowers on her grave.

L. F.

Red Oak, Iowa.

I have been in bed for two months with rheumatism, and I look forward to the coming of Young People with very great pleasure.

I think the picture of "Harry and Dan" is very pretty indeed. I have not been able to walk any distance for more than a year, and I think it would be real nice to have such a pretty goat and sleigh.

I am very glad Young People disapproves of disturbing birds' nests. I always thought it was very cruel.

Gracie M.

Batavia, Iowa.

We think the Post-office Box, and everything in Young People, are interesting. My brother Ernest likes "Toby Tyler" the best.

My little sister Mabel, two years old, can sing every tune she hears once. She likes "Kissing through the Chair," in Young People No. 57. She calls it "Peep Ho." She gets in the rocking-chair every day, and rocks, and sings the first verse over and over for a long time.

Minnie H.

Warthen, Georgia.

I am thirteen years old. I take Young People, and like it very much. I go to school nine miles from this place, and come home every Friday evening. I call for my paper on my way, and I read it to my little brother and sister. They are much pleased and interested with the stories and pictures.

I have two pet lambs, named Annie Bell and Ellinore, that follow me everywhere I go. They are about a year old.

I hope Young People will be in the hands of all the boys and girls.

Bessie W.

I have no more postmarks, but I will exchange stamps, for curiosities or foreign stamps.

George N. Prentiss, Watertown, Wis.

All my silver ore is exchanged, but I will exchange a few foreign stamps, a piece of coral, some Florida shells, and some other curiosities, for a genuine Indian bow and arrow in good order for shooting.

Fred Pfans, Jun.,

11 Beaver Street, Newark, N. J.

I am a little girl thirteen years old. I take Young People, and like it very much. I like Bessie Maynard's "Sea-Breezes."

I would like to exchange sea-shells and other small curiosities for old coins or odd bits of money.

Virgie McLain, care of U. S. Consul,

Nassau, N. P., Bahamas.

M. D. Austin, Buffalo, N. Y., wishes to inform correspondents that his stock of Sandwich Island and Canadian stamps is exhausted, and he accordingly withdraws his name from our exchange List.

The following exchanges are desired by correspondents:

Postmarks and beetles, for butterflies and moths.

George A. Hough,

95 Elm Street, New Bedford, Mass.

Foreign stamps, for a 5-cent, 30-cent, or 90-cent United States stamp, issue of 1851 to 1860; a 90-cent, issue of 1861, envelope or newspaper stamps, except 1-cent, 2-cent, and 3-cent, or any Department stamps except Interior and Treasury.

R. L. Brackett, P. O. Box 4494, New York City.

Postage stamps, crests, and monograms.

F. P. Caroll,

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada.

Foreign and United States postage stamps, for minerals and coins.

Daniel T. Jay,

P. O. Box 611, Emporia, Kan.

Canadian, East Indian, English, and old issues of United States stamps, for stamps from Russia, Persia, China, and other foreign countries.

Subscriber to "Young People,"

31 Thorp Block, Indianapolis, Ind.

Pressed autumn leaves, postmarks, and stamps, for minerals, Florida moss, or any curiosity.

Belle de Lamater,

125 Fourth Street, Jackson, Mich.

Danish, German, Italian, East Indian, or British stamps, for other foreign stamps, or for Indian curiosities.

L. B. Brickenstein,

Lititz, Lancaster County, Penn.

United States postage and Department stamps, for other stamps.

Chancy Whitney,

P. O. Box 1552, Muskegon, Ottawa County, Mich.

English and German stamps, for stamps of any other foreign country.

Anna J. Davison,

St. Edward, Boone County, Neb.

Quartz, Indian arrow-heads, rocks from the Mammoth Cave, some shells from the Dead Sea, and sea-oates, for amethysts or other curiosities.

Willis G. White, Yorkville, S. C.

Six different War Department stamps, for a stamp from India, China, Egypt, or any South American country.

Clem Flagler,

Rock Island Arsenal, Rock Island, Ill.

Twenty-five postmarks, for five foreign stamps.

George H. Ashley,

20 North Washington Street, Rochester, N. Y.

Fourteen Ohio postmarks, for two rare foreign stamps.

Fred W. Adams,

Warren, Trumbull County, Ohio.

Virginia and Lake Superior iron ores, for insects, minerals, or Indian arrow-heads. Stones and soil from Ohio, for sea-shells.

Alex. C. and Lulu A. Bates,

1115 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio.

English and Cuban stamps, for other foreign stamps.

J. D. J. B.,

129 Broadway, South Boston, Mass.

United States stamps, for foreign stamps.

Jessie R. Bentley,

Marshall, Calhoun County, Mich.

Foreign stamps, specimens of wood, foreign and United States postmarks, slate showing formation of coal, or soil of Illinois, for rare foreign or United States Department stamps, or ocean curiosities.

Edward T. Rea,

P. O. Box 531, Urbana, Champaign County, Ill.

Petrified coral, zinc ore, or a piece of volcanic rock from Italy, for a specimen of lead or copper ore.

Allen R. Benson,

51 Seventh Street, Hoboken, Hudson Co., N. J.

Indian arrow-heads and rattlesnake rattles, for ocean curiosities.

J. P. Crozier,

Carlyle, Allen County, Kansas.

Twenty foreign postage stamps (no duplicates), for twenty others.

George L. Rusby,

Franklin, Essex County, N. J.

Stamps, for minerals.

W. Miller,

1743 North Seventh Street, Philadelphia, Penn.

Rare postage stamps.

Clarence G. White,

1581 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio.

A piece of Quincy granite, for ten stamps of any foreign country except England, France, and Germany.

W., P. O. Box 208, Milton, Mass.

Fifty postmarks or twenty-five stamps, for ocean shells.

Louis C. Grime,

Mohrsville, Berks County, Penn.