| Etext transcriber’s note: The footnotes have been located after the etext. Corrections of some obvious typographical errors have been made (a list follows the etext); the spellings of several words currently spelled in a different manner have been left un-touched. (i.e. chesnut/chestnut; every thing/everything; Our’s/Ours; Codoba/Cordoba; sanitory/sanitary; your’s/yours; janty/jaunty; visiters/visitors; negociation/negotiation.) The accentuation of words in Spanish has not been corrected or normalized. |

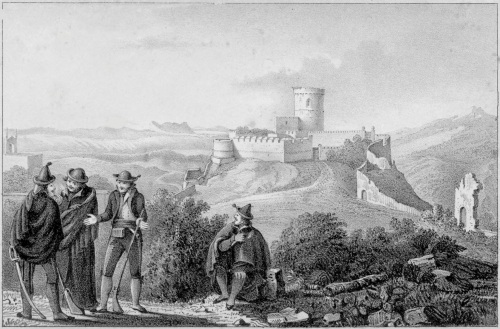

On Stone by T. J. Rawlins from a Sketch by Capt C. R. Scott

R. Martin lithog 26, Long Acre

CASTLE OF XIMENA, AND DISTANT VIEW OF GIBRALTAR

Published by Henry Colburn, 13 Great Marlborough St.

![]()

BY

CAPTAIN C. ROCHFORT SCOTT,

AUTHOR OF “TRAVELS IN EGYPT AND CANDIA.”

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, PUBLISHER,

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

—

1838.

LONDON:

F. SHOBERL, JUN. 51, RUPERT STREET, HAYMARKET.

———

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

Departure from Cordoba—Post Road to Cadiz—Carlota—Ecija—Carmona—Road from Ecija to Gibraltar—Locusts—Osuna—Saucejo—An Olla in perfection—Ronda—Splendid Scenery on the road to Grazalema—Distant View of Zahara—Grazalema—Extensive Prospect from the Pass of Bozal—Secluded Orchards of Benamajama—Pajarete—El Broque—Ubrique—Difficult Road across the Mountains to Ximena—Our Guide in a rage—Fine Scenery—Ximena—Strength of its Castle—Road to Gibraltar | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

Departure for Cadiz—Road round the Bay of Gibraltar—Algeciras—Sandy Bay—Gualmesi—Tarifa—Its Foundation—Error of Mariana in supposing it to be Carteia—Battle of El Salado—Mistake of La Martiniere concerning it—Itinerary of Antoninus from Carteia to Gades verified—Continuation of Journey—Ventas of Tavilla and Retin—Vejer—Conil—Spanish Method of Extracting Good from Evil—Tunny Fishery—Barrosa—Field of Battle—Chiclana—Road to Cadiz—Puente Zuazo—San Fernando—Temple of Hercules—Castle of Santi Petri—Its Importance to Cadiz | 33 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

Cadiz—Its Foundation—Various Names—Past Prosperity—Made a Free Port in the hope of ruining the trade of Gibraltar—Unjust Restrictions on the Commerce of the British Fortress—Description of Cadiz—Its vaunted Agremens—Society—Monotonous Life—Cathedral—Admirably built Sea Wall—Naval Arsenal of La Carraca—Road to Xeres—Puerto Real—Puerto de Santa Maria—Xeres—Its Filth—Wine Stores—Method of Preparing Wine—Doubts of the Ancient and Derivation of the Present Name of Xeres—Carthusian Convent—Guadalete—Battle of Xeres | 64 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

Choice of Roads to Seville—By Lebrija—Mirage—The Marisma—Post Road—Cross Road by Los Cabezas and Los Palacios—Difficulty of Reconciling any of these Routes with that of the Roman Itinerary—Seville—General Description of the City—The Alameda—Display of Carriages—Elevation of the Host—Public Buildings—The Cathedral—Lonja—American Archives—Alcazar—Casa Pilata—Royal Snuff Manufactory—Cannon Foundry—Capuchin Convent—Murillo—Theatre of Seville—Observations on the State of the National Drama—Moratin—The Bolero—Spanish Dancing—The Spaniards not a Musical People | 90 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

Society of Seville—Spanish Women—Faults of Education—Evils of Early Marriages, and Marriages de Convenance—Environs of Seville—Triana—San Juan De Alfarache Santi Ponce—Ruins of Italica—Italica not so ancient a City as Hispalis—Young Pigs and the Muses—Departure from Seville—The Marques De Las Amarillas—Weakness, Deceit, and Injustice of the Late King of Spain—Alcala De Guadiara—Utrera—Observations on the Strategical Importance of this Town—Moron—Military operations of Riego—Apathy of the Serranos during the Civil War—Olbera—Remarks on the Itinerary of Antoninus | 123 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

Ronda to Gaucin—Road to Casares—Difficulty in Procuring Lodgings—Finally Overcome—The Cura’s House—View of the Town from the Ruins of the Castle—Its Great Strength—Ancient Name—Ideas of the Spaniards regarding Protestants—Scramble to the Summit of the Sierra Cristellina—Splendid View—Jealousy of the Natives in the matter of Sketching—The Cura and his Barometer—Departure for the Baths of Manilba—Romantic Scenery—Accommodation for Visiters—The Master of the Ceremonies—Roads to San Roque and Gibraltar—River Guadiaro and Venta | 154 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

The Baths of Manilba—A Specimen of Fabulous History—Properties of the Hedionda—Society of the Bathing Village—Remarkable Mountain—An English Botanist—Town of Manilba—An Intrusive Visiter—Ride to Estepona—Return by way of Casares | 179 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

A Shooting Party to the Mountains—Our Italian Piqueur, Damien Berrio—Some Account of his Previous Life—Los Barrios—The Beautiful Maid, and the Maiden’s Levelling Sire—Road to Sanona—Reparation against Bandits—Arrival at the Caseria—Description of its Owner and Accommodations—Fine Scenery—A Batida | 202 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

Luis de Castro | 226 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

Don Luis’s Narrative is interrupted by a Boar—The Batida resumed—Departure from Sanona—Road to Casa Vieja—The Priest’s House—Adventure with Itinerant Wine-Merchants—Departure from Casa Vieja—Alcala De Los Gazules—Road to Ximena—Return to Gibraltar | 249 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

Departure for Madrid—Cordon drawn round the Cholera—Ronda—Road to Cordoba—Teba—Erroneous Position of the Place on the Spanish Maps—Its Locality agrees with that of Ategua, as described by Hirtius, and the Course of the River Guadaljorce with that of the Salsus—Road to Campillos—The English-loving Innkeeper and his Wife—An Alcalde’s Dinner spoilt—Fuente De Piedra—Astapa—Puente Don Gonzalo—Rambla—Cordoba—Meeting with an old Acquaintance | 267 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

History of Blas El Guerrillero—continued | 294 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

Unforeseen Difficulties in Proceeding to Madrid—Death of King Ferdinand—Change in our Plans—Road to Andujar—Alcolea—Montoro—Porcuna—Andujar—Arjono—Torre Ximeno—Difficulty of Gaining Admission—Success of a Stratagem—Consternation of the Authorities—Spanish Adherence to Forms—Contrasts—Jaen—Description of the Castle, City, and Cathedral—La Santa Faz—Road to Granada—Our Knightly Attendant—Parador de San Rafael—Hospitable Farmer—Astonishment of the Natives—Granada—El Soto de Roma—Loja—Venta de Dornejo—Colmenar—Fine Scenery—Road from Malaga to Antequera, and Description of that City | 325 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

Malaga—Excursion of Marbella and Monda—Churriana—Benalmania—Fuengirola—Discrepancy of Opinion respecting the Site of Suel—Scale to be adopted, in order to make the measurements given in the Itinerary of Antoninus agree with the Actual Distance from Malaga to Carteia—Errors of Carter—Castle of Fuengirola—Road to Marbella—Tower and Casa Fuertes—Disputed Site of Salduba—Description of Marbella—Abandoned Mines—Distance to Gibraltar | 363 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

A Proverb not to be lost sight of whilst travelling in Spain—Road to Monda—Secluded Valley of Ojen—Monda—Discrepancy of Opinion respecting the Site of the Roman City of Munda—Ideas of Mr. Carter on the Subject—Reasons adduced for concluding that Modern Monda occupies the Site of the Ancient City—Assumed Positions of the Contending Armies of Cneius Pompey and Cæsar, in the Vicinity of the Town—Road to Malaga—Towns of Coin and Alhaurin—Bridge over the Guadaljorce—Return to Gibraltar—Notable Instance of the Absurdity of Quarantine Regulations | 382 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

The Knight of San Fernando | 410 |

| 439 | |

DEPARTURE FROM CORDOBA—POST-ROAD TO CADIZ—CARLOTA—ECIJA—CARMONA—ROAD FROM ECIJA TO GIBRALTAR—LOCUSTS—OSUNA—SAUCEJO—AN OLLA IN PERFECTION—RONDA—SPLENDID SCENERY ON THE ROAD TO GRAZALEMA—DISTANT VIEW OF ZAHARA—GRAZALEMA—EXTENSIVE PROSPECT FROM THE PASS OF BOZAL—SECLUDED ORCHARDS OF BENAMAJAMA—PAJARETE—EL BROQUE—UBRIQUE—DIFFICULT ROAD ACROSS THE MOUNTAINS TO XIMENA—OUR GUIDE IN A RAGE—FINE SCENERY—XIMENA—STRENGTH OF ITS CASTLE—ROAD TO GIBRALTAR.

ON leaving Cordoba, we turned our horses’ heads homewards, taking the arrecife, or high road, to Seville and Cadiz. This appears to follow the direct Roman military way given in detail in the Itinerary of Antoninus; the distances from station to station, on the modern road, agreeing perfectly with those specified in the Itinerary, which, as it runs very straight as far as Ecija, would not be the case if the Roman road had diverged either to the right or left, as some are disposed to make it, placing Adaras (one of the intermediate stations) on the margin of the Guadalquivír.

Several monuments, bearing inscriptions alluding to this military way, are preserved at Cordoba. They all describe it as being from the temple of Janus to the Bœtis, (meaning, it must be presumed, the mouth of the river) and to the ocean.

The road is no longer paved, as it is described to have been in those days; but, nevertheless, it is good enough to enable a lumbering diligence to pulverize the gravel daily on its tedious way between Madrid and Seville. It is also furnished with relays of post horses,[1] but the posting establishments being, as in most other countries of Europe, under the direction of the government, is a satire upon the term post haste.

From Cordoba to Ecija is ten leagues.[2] The road, on reaching the river Badajocillo, or Guadajoz, which is crossed by a lofty stone bridge, commanding a fine view of Cordoba, leaves the rich alluvial valley of the Guadalquivír, and enters upon an undulated tract of country, that extends nearly all the way to Ecija. At three leagues is the scattered village and post-house of Mango-negro, and three leagues beyond that again, the settlement of Carlota. The ride is most uninteresting; as, besides being tamely outlined and thinly peopled, the country is nearly destitute of wood, and, in the summer season, of water; though, judging from the extraordinary number of bridges, especially on drawing near Carlota, there must be a superabundance in winter. Carlota is one of the numerous villages which Charles the Third colonized from the Tyrol. It consists principally of isolated cottages, standing some hundred yards apart, and the same distance from the road; but there is a small congregation of houses round the chapel, post-house, and Casa del Ayuntamiento,[3] and a Gasthof, which I can say, from personal experience, would do no discredit to Innsbruck itself.

The parish contains 250 houses, and a population of 1500 souls. The fields round Carlota certainly appear to be better tilled than those in other parts of the country, and there is a German tidiness about its white cottages, as well as a platterfacedness about the little white-headed urchins assembled round the doors, that are quite anti-Spanish.

We obtained an excellent dinner at the Tyroler Adler, and, in the afternoon, taking a by-road that struck off from the post route to the right, cantered through plantations of olives nearly all the way to Ecija,—four leagues. In the whole of the distance we did not see a drop of running water, until we arrived on the brow of the hill overlooking the river Genil. From this spot there is a fine view of the city of Ecija, situated on the opposite bank.

The volume of the Genil increases but little between Granada and Ecija; for its principal feeders, though falling into it below Granada, are expended in irrigating the vega; and the salados, on the western side of the Serranía de Ronda, are mostly dry during the summer. In winter, however, the Genil is so increased, that the bridge at Ecija (a solid stone structure of eleven arches,) is carried quite across the valley, although the bed of the river is not above 100 yards wide.

Ecija is the Astigi of the Romans. It stands on a gentle acclivity, some little distance from the Genil, and bears evident marks of antiquity. Almost all traces of its walls have disappeared, however; and what little remains of its tapia-built castle shows it to have been a work of the Moors. The principal streets are wide, and contain many good houses; and the plaza is particularly well worth a visit from the lovers of the picturesque.

The city contains sixteen convents, and two hospitals, with churches in proportion. None of them offers much to interest the protestant traveller; but, I believe, several boast of possessing valuable relics. The Royal stud-house is fast going to decay.

The population of Ecija is estimated at 30,000 souls; a number that appears totally disproportioned to the size of the city; particularly, as it contains but a few tanneries, and trifling manufactories of shoes, saddlery, &c. But, from the extreme fertility of the soil in its neighbourhood—considered the most productive and best cultivated in Andalusia—it is very possible this amount may not be exaggerated; for in Spain the agriculturalists do not scatter themselves about in small villages and hamlets over its surface, as in other countries, but assemble together in large towns; so that those places which are situated in fertile districts are as densely populated as our manufacturing towns.

The distance that a Spanish peasant sometimes travels daily, to and from his work, is truly surprising, in a people that, generally speaking, like to save themselves trouble. Whilst getting in the harvest, however, they erect ranchas, or rush huts, to shelter them from the midday sun and night dews, and dwell in these temporary habitations until their work is completed.

The crops of corn in the neighbourhood of Ecija are remarkably fine, yielding forty to one, and though not so tall, perhaps, as those of the vega of Granada, the grains are larger and better ripened.

I must not omit to say a good word for the Posada,—the Post-house,—which I do the more willingly from being so seldom called upon to speak in terms of commendation of Spanish “houses of entertainment.” Suffice it to observe, that, provided the traveller be very hungry, and moderately fatigued, he may reckon on getting a supper that he will be able to eat, and a bed whereon—albeit hard—he may obtain some hours’ unmolested repose.

The remainder of the post road to Seville is so perfectly uninteresting, that, reserving the Andalusian capital for a future tour, I shall take a more direct route back to Gibraltar, through the Serranía de Ronda; merely offering a few remarks on the town of Carmona, which is situated about two thirds of the way between Ecija and Seville, and referring my readers to the Itinerary in the Appendix for any further details as to the distances from place to place along the road.

Carmona is one of the few Roman towns of Bœtica of whose identity there is scarcely a doubt; its name having undergone little or no change. It is mentioned by most of the ancient writers, and called by them, indifferently, Carmo and Carmona, and by Julius Cæsar was esteemed one of the strongest posts in the whole country. Its position, considered relatively with the adjacent ground, is, indeed, most commanding; being on the edge of a vast plateau of very elevated land, which, stretching many miles to the south, falls abruptly along the course of the river Corbones.

The Roman name for this river is, I think, doubtful. Florez, and most antiquaries, suppose it to be the Silicensis. Some, and, as it appears to me, with better reason, give that name to the Badajocillo. Be that as it may, the Corbones is but an inconsiderable stream, and is now crossed by a stone bridge of three arches.

The ascent to Carmona is very steep and tedious. The city is entered through a triumphal Roman arch, which was repaired and spoilt by order of Charles III. Another Roman gateway stands at the southern extremity of the town, by which the road to Seville leaves it; and various parts of the walls which yet encompass the place are the work of the same people. The castle, however, is a relique of the Moors, and in a very ruinous condition.

This stronghold was wrested from the Moors by San Fernando, after a six months’ investment. It was a favourite place of residence of Peter, surnamed the Cruel, who, looking upon it as impregnable, left his children there in fancied security when he took the field for the last time against his brother. Soon after Peter’s death, however, it fell into the hands of his rival, who, according to some accounts, caused the children (his nephews) to be put to death in cold blood.

The streets of Carmona are wide, clean, and well-paved; and the alameda is enchanting, commanding a superb view of the ruined fortress, and over the rich vales of the Corbones, and more distant Guadalquivír, and embracing, at the same time, the whole chain of the Ronda mountains to the eastward.

The population of the place is about 10,000 souls. The inn is execrable.

The post road to Cadiz is directed from Carmona on Alcalà de Guadiara, where a branch to Seville strikes off, nearly at a right angle, to the east, thereby making a considerable détour. But in summer, carriages even may proceed to Seville by a cross road, which not only lessens the dust, but reduces the distance from six long to the same number of short leagues; or, in other words, effects a saving of about three miles.

I now return to Ecija, and take the road from that city to Osuna; which is tolerably good, and practicable for carriages during the greater part of the year. The distance is five (very long) leagues. The country presents a slightly undulated surface, and, excepting round the edges of some basins wherein extensive lakes have been formed, is altogether under the plough. At a little distance from the road, on the left hand, a stream, called El Salado, flows towards the Genil. It does not communicate with these lakes, nor has the name it bears been given from its being impregnated with salt.

During our ride, we observed a number of men advancing in skirmishing order across the country, and thrashing the ground most savagely with long flails. Curious to know what could be the motive for this Xerxes-like treatment of the earth, we turned out of the road to inspect their operations, and found they were driving a swarm of locusts into a wide piece of linen spread on the ground at some distance before them, wherein they were made prisoners. These animals are about three times the size of an English grasshopper. They migrate from Africa, and their spring visits are very destructive; for in a single night they will entirely eat up a field of young corn.

The Caza de Langostas[4] is a very profitable business to the peasantry; as, besides a reward obtained from the proprietor of the soil in consideration for service done, they sell the produce of their chasse for manure at so much a sack.

Osuna is generally admitted to be the Urso,[5] Ursao, and Ursaon, of the Roman historians; though it agrees in no one particular with the description given of that place by Hirtius; for it is not by any means “strong by nature;” it is in the vicinity of extensive forests—rendering it perfectly absurd to suppose that Cæsar’s troops “had to bring wood thither all the way from Munda;"—and, so far from “there being no rivulet within eight miles of the place,”[6] a fine stream meanders under its very walls.

The town is situated at the foot of a hill that screens it effectually to the eastward, and the summit of which is occupied by an old castle of considerable strength and size, but now fast crumbling to decay. The streets are wide and well paved, the houses particularly good;—indeed, some of the palaces of the provincial nobility (with whom it was formerly a favourite place of residence) are strikingly handsome; in particular, that of the Duke who takes his title from the city; and notwithstanding that the streets are overgrown with grass, and the houses covered with mildew, I am, nevertheless, disposed to call Osuna the best built and handsomest city in Andalusia, it contains a university, fourteen convents, for both sexes, and a population of 16,000 souls; but has little or no trade—in fact, though on the crossing of two high roads, (viz., from Gibraltar to Madrid, and from Granada to Seville) it has all the dullness of a secluded country village.

The vicinity is very fruitful in olives and corn; the soil is a whitish clay. To the S.E. the country is tolerably level all the way to Antequera, and to the west is nearly flat to Seville; but at about a mile southward from the city, shoot up the entangled roots of the mountains of Ronda, presenting on that side a belt of very intricate country. There are two roads to that place, the distance by the better, which, I think, is also rather the shorter, of the two, is nine leagues. It leaves Osuna by the gate of Granada, and, crossing the before-mentioned stream (which is one of the sources of the Corbones), advances some distance along a wide olive-planted valley. It then quits the great road to Granada (which continues along the valley), and ascends a steep and very long hill, from the crest of which, distant about three miles from Osuna, there is a splendid view of the city, and of the spacious plains extending to and bordering the distant Guadalquivír, studded with the towns of Marchena, Fuentes, Palmar, and Carmona.

The road continues along the summit of the elevated range of hills which it has now attained, for about five miles, winding amongst some singularly mammillated hummocks, that have very much the appearance of the tumuli left in an exhausted mining country. A succession of strongly marked and peculiarly rugged ravines present themselves along the eastern side of the ridge, and the ground falls also very abruptly in the opposite direction; but to the south, whither the road is directed, the descent is much more gradual; and from the foot of the hill, which is bathed by a rivulet wending its way to the Genil, the country is tolerably level, and the road extremely good the remaining distance to Saucejo.

In former days, this route was practicable for carriages throughout, and with very little labour it might again be made so; but, though the high road from the capital to Algeciras and Gibraltar, it is but little travelled. The other road from Osuna to Ronda joins in here on the right.

The village of Saucejo is a post station three leagues from Osuna, and six from Ronda. It contains some eight hundred inhabitants, great abundance of stabling, but not one decent house. The posada is a peculiarly unpromising establishment, and the landlady’s face such as to shut out all hope of any sound wine being found within its influence. We had left Osuna so late in the day, however, that it would have been vain to attempt reaching Ronda ere nightfall.

We, therefore, reluctantly took possession of the sala, and, presenting our sour-faced hostess with a rabbit and some partridges that we had purchased on the road, asked if she could furnish the other requisites for the concorporation of an olla, and whether it would be possible to let us have our meal ere midnight; to both of which questions, with sundry consequential nods of the head, she replied severally, en casa llena, presto se guisa la cena.[7] Notwithstanding this assurance, our supper was long in making its appearance, for the operations of an olla cannot be hurried. But, when it did come, it bespoke our landlady to be a cordon bleu of the first class; the pimento[8] had been administered with judgment; the berza[9] had duly extracted the flavour from the rabbit and partridges; the chorizo[10] had imparted but the desirable smack of garlic to the other ingredients; and the nutty savour of the tocino[11] was beyond all praise. Nor was her wine such as we had expected; though somewhat too light to have much influence on the digestion of the unctuous mess placed before us.

From Saucejo the road again branches into two, one route proceeding by way of Almargen, the other by the Venta del Granadal. Both are reckoned six leagues; but the last mentioned is better than the other, as well as shorter by several miles. It crosses a considerable stream (here called the Algamitas, but which is, in fact, the main source of the Corbones) by a ford, about three miles from Saucejo. The descent to the stream is very bad, and, after keeping along its bank for another mile, the road mounts to some elevated table land, from which the view to the westward is obstructed by the rocky peaks of two detached mountains about a mile off. These may be considered the outposts of the Serranía in that direction; and, on the rough side of the more considerable of the two, is the Hermita de Caños Santos.

The country becomes very wild as the road advances, and rugged tors, partially covered with wood, rise on all sides. At nine miles from Saucejo is the lone venta of Grañadal, and beyond it the mountains rise to a yet greater height, but their slopes are less abrupt, and are covered with forests of oak and cork. At twelve miles a track branches off to the right, proceeding to the little town of Alcalà del Valle, which, though distant only about half a mile, is not visible from the road. Soon after, a wide valley opens to the view, at the bottom of which, encased by steep rocky banks, flows the river Guadalete. This river is by some considered the Lethe of the ancients; but, if it be so, our long-cherished notions of the beauty of the Elysian fields have been wofully faulty, for the country is rather tame, and the soil stony and ungrateful. Thus far, however, it answers the description of Virgil, that you

The town of Setenil is perched on a crag overhanging the left bank of the Guadalete, and distant about three miles from the road, which keeps under the broad summit of the hills forming the northern boundary of Elysium. The sides of these are partially cultivated, and, from time to time, a low cottage is met with as the road proceeds; but it soon enters a cork-forest, and, threading its dark mazes for about four miles, gradually gains the crest of the chain of hills overlooking the vale of Ronda to the north, whence a splendid view is obtained of the fertile basin, its rock-built fortress, and jagged sierras.

The descent on the southern side of the hills is rather rapid, and, after proceeding downwards about a mile, the road is joined on the left by the other route from Saucejo. From hence to Ronda is two short leagues. The road still continues descending for another mile; and, in the course of the two following, it crosses three deep ravines, watered by copious streams, and planted with all sorts of fruit-trees.

In the bottom of one of these dells is ensconced the village of Arriate. The last is a deep and very singular rent that extends, east and west, quite across the basin of Ronda. Immediately after crossing this fissure, the road begins to ascend the range of hills whereon Ronda is situated, and, after winding for three miles amongst vineyards, olive grounds, and corn-fields, enters the city on its north side.

We were seven hours performing the journey, although the distance is but six leguas regulares.

I have already given so full a description of Ronda, that I will pass on without further remark.

To vary the scenery, and moved by curiosity to visit some of the scenes of our acquaintance Blas’s exploits, we determined to take a somewhat circuitous route homewards, by way of Grazalema and Ubrique.

The distance to the first named town is three long leagues. The road descends gradually to the south-western extremity of the basin of Ronda, where the Guadiaro, forming its junction with the Rio Verde, enters a rocky defile, and is lost sight of amidst the roots of the rugged sierras that spread themselves in all directions towards the Mediterranean.

Crossing the last named stream just before its confluence with the Guadiaro, the road at once begins ascending towards a deeply marked gap, that breaks the ridge of the mountains which rise along the right bank of the stream.

The pass is about four miles from Ronda, and commands a splendid view of the fruitful valley, which lies, like an outspread cornucopia, at its foot. On the other side, too, the scenery is not less fine, though of a totally different nature. There a singular double-peaked crag rises up boldly and darkly on the left hand, casting its shadow on the bright foliage of an oak forest, which, deep sunk below the rest of the country, spreads its verdant covering as far to the eastward as where the huge Sierra Endrinal raises its cloud-enveloped head above all the other mountains of the range. High seated on the side of this, a white speck is seen which, in the course of time, proves to be the town of Grazalema, whither we are bending our steps.

Proceeding onwards, from the pass about a mile, the little village of Montejaque shows itself, peeping from between the two peaks of the mountain on the left, and, seemingly, quite inaccessible, even to a goat.

It is inhabited by a horde of half-tamed Saracens, who pride themselves greatly on having foiled all the attempts of the French to make themselves masters of the place;[12] and, as this elevated little village is but three quarters of a mile from the high road, (which is the principal communication between Malaga and Cadiz) it must have possessed the means of annoying the enemy considerably.

For the next two miles our way lay along the spine of a somewhat elevated ridge; whence we looked down upon the before-mentioned wooded country on one side, and on the other into a well cultivated valley. From the bed of this, but at several leagues’ distance, the rock-built town of Zahara rears its embattled head.

This little fortress is very noted in Moorish history; its capture by Muley Aben Hassan, during a period of truce, having provoked the renewal of the war which led to the loss of the crown, not only to himself first, but to his race afterwards.

One of the sources of the Guadalete flows in this valley, bathing the walls of Zahara, which stands on the site of the Roman town of Lastigi.[13] The present name, I should imagine, (considering the locality) is derived rather from the Arabic word Zaharat (mountain top) than Zāhara, (flowery) as supposed by Mr. Carter; for the streets are cut out of the live rock on which the place is built.

The road to Grazalema, now mounting another step, enters a dark forest, and, continuing for five miles along the top of a narrow ridge, descends into a vine-clad valley, that spreads out at the foot of the rough sierra on the side of which Grazalema is seated.

The ascent to the town is very bad, and is rendered worse than it otherwise would be by being paved—for a paved road in Spain is sure to be neglected. We scrambled up with much difficulty, and alighting at the posada, remained for an hour or two, to procure some breakfast, and examine the place.

It is a singularly built town, the streets being heaped one above another, like steps; and in several instances they are even worked out of the native rock. There is, nevertheless, a fine open market-place, which we found well supplied with fruit, vegetables, and game, including venison and wild boar; and the town possesses several manufactories of coarse cloths and serges.

From its situation, immediately over the mouth of a deep ravine, by which alone access can be obtained to one of the principal passes in the Serranía, Grazalema occupies a very important military position, and may be considered almost inassailable; for, whilst at its back a perfectly impracticable mountain covers it from attack, it is protected to the north and east by the precipitous ravine it overlooks; up the side of which, even the narrow road from Ronda has not been practised without much labour. The only side, therefore, on which it has to apprehend danger, is that fronting the pass above it—i.e. to the westward. But it has the means of offering an obstinate resistance, even in that direction.

Commanding, as it thus does, so important a passage over the mountains, there can be but little doubt that Grazalema stands upon, or near, the site of some Roman fortress; and, for reasons which I shall hereafter mention, I feel inclined to place here the town of Ilipa.[14]

The inhabitants amount to about 6,000, and are a savage, ruffianly-looking race. During the “War of Independence,” assisted by their brethren of the neighbouring mountain fastnesses, they frequently rose against their invaders, driving them out of the place; and on one occasion they repulsed a French column of several thousand men, which was sent to dispossess them of their stronghold.

On leaving Grazalema, the road enters the narrow, rock-bound ravine leading up to the pass, down which a noisy torrent rushes, leaping from precipice to precipice, and lashing the base of the crag-built town, whence we had just issued. A newly-built bridge, whose high-crowned arch places it beyond the anger of the foaming stream, gives a passage to the road to Zahara, which winds along the eastern face of the Sierra del Pinar. Our route, however, continues ascending yet a mile and a half along the right bank of the torrent, ere it reaches the long descried gap in the mountain chain, the name of which is El Puerto Bozal.

This is considered one of the most elevated passes in the whole Serranía de Ronda, and must be at least 4,000 feet above the level of the sea. The mountains on either side rise to a far greater elevation; that on the right, distinguished by the name of El Pico de San Cristoval, is said (as has already been stated) to have been the first land made by Columbus on his return from the discovery of the “New World.”

The views from this pass are truly grand. At our backs lay the beautifully wooded country we had travelled over in the morning—Ronda and its vale, and the distant sierras of El Burgo and Casarabonela. Before us, a wild mountain country extended for several miles; and beyond, spreading as far as the eye could reach, were the vast plains of Arcos, through which the gladdening Guadalete, winding its way past Xeres, turns to seek the bay of Cadiz, whose glassy surface the white walls of its proud mistress, and the deep blue ocean, could be seen distinctly on the left, though at a distance of more than fifty miles.

From the Puerto Bozal, a trocha, directed straight upon Ubrique, strikes off to the left; but the saving in point of distance which this road offers, is counterbalanced by its extreme ruggedness. We, therefore, took the more circuitous route to that place by El Broque, which, for the first five miles, is itself sufficiently bad to satisfy most people. The views along it, looking to the south, are very fine; but the lofty barren range of San Cristoval, on the side of which it is conducted, shuts out the prospect in the opposite direction.

At length, crossing over a narrow tongue that protrudes from the side of the rugged mountain, we entered a dark, wooded ravine, and began to descend very rapidly, and, to our astonishment, by a very good road. After proceeding in this way about a mile, the valley gradually expanding, we emerged from the wood, and found ourselves in a sequestered glen of surpassing loveliness. A neat white chapel, with a picturesque belfry, stood on a sloping green bank on our right hand, and, scattered in all directions about it, were the trim, vine-clad cottages of its frequenters, each screened partially from the sun in a grove of almond, cherry, and orange trees. A crystal stream gurgled through the fruitful dell, which was bounded at some little distance by high wooded hills and rocky cliffs.

This secluded retreat is called La Huerta[15] de Benamajáma,—the peculiarly guttural name proving it to have been a little earthly paradise of the Moors.

The road, which had thus far been nearly west, here, continuing along the course of the little river Posadas, turns to the south; and, keeping under a range of wooded hills on the left hand, in about an hour reaches El Broque. This portion of the road is very good, and from it, looking over the great plain bordering the Guadalete, may be seen the lofty tower of Pajarete, perched on a conical mound, at about a league’s distance. The justly celebrated sweet wine called by this name was originally produced from the vineyards in its vicinity, but it is now made principally at Xeres.

El Broque is a small clean town, abounding in wood and water, and containing from 1500 to 2000 inhabitants. To the east it is overshadowed by a range of lofty, wooded hills, which may be considered the last buttresses of the Serranía; for the road to Cadiz, which here branches off to the right, crossing the Posadas, traverses an uninterrupted plain all the way to Arcos.

The route to Ubrique, on the other hand, again strikes into the mountains; though, for yet two miles further, it follows the course of the little river and its impending sierra. Arrived, however, at the mouth of a ravine, which brings down another mountain-torrent to the plain, it turns to the north, keeping along the margin of the stream, until the bridge of Tavira offers the means of passage; when, crossing to the opposite bank, it once more enters the intricate belt of mountains.

The name of the stream which is here crossed is the Majaceite; and on its right bank, close to the bridge, is a solitary venta. The scenery is extremely beautiful. The mountains of Grazalema, which we had traversed in the morning, form the background; the ruined tower of Alamada, perched on an isolated knoll, stands boldly forward in middle distance; and close at hand are the rough, coppiced banks and crystal current of the winding Majaceite.

From hence to Ubrique the country is very wild and rugged. The town is first seen (when about a league off) from the summit of a round-topped hill, six miles from El Broque. It is nestled in the bottom of a deep valley, hemmed in by singularly rugged mountains. The first part of the descent is gradual, but a steep neck of land must be crossed ere reaching the town; and, as if to render the approach as difficult as possible, the road over this mound has been paved.

Amongst the rude masses of sierra that encompass Ubrique, numerous rivulets pierce their way to the lowly valley, where, collected in two streams, they are conducted to the town, and, fertilizing the ground in its neighbourhood, cause it to be encircled by a belt of most luxuriant vegetation. The mountains in the vicinity abound also in lead-mines, but they are no longer worked. “Where are we to find money? Where are we to look for security?” were the answers given to my question, “Why not?”

The streets of Ubrique are wide, clean, and well paved; the houses lofty and good; but the inn, alas! affords the wearied traveller little more than bare walls and a wooden floor. The population of the place may be estimated at 8000 souls. It contains some tanneries, water-mills, and manufactories of hats and coarse cloths. It does not strike me as being a likely site for a Roman city.

We were on horseback by daybreak, having before us a long ride, and, for the first five leagues (to Ximena), a very difficult country to traverse. For about a mile the road is paved, and confined to the vale in which Ubrique stands by a precipitous mountain. But, the westernmost point of this ridge turned, the route to Ximena (leaving a road to Alcalà de los Gazules on the right) takes a more southerly direction than heretofore, and, entering a hilly country, soon dwindles into a mere mule-track. Ere proceeding far in this direction, another road branches off to Cortes, winding up towards some cragged eminences that serrate the mountain-chain on the left. The path to Ximena, however, continues yet two miles further across the comparatively undulated country below, which thus far is under cultivation; but, on gaining the summit of a hill, distant about four miles from Ubrique, a complete change takes place in the face of the country; the view opening upon a wide expanse of forest, furrowed by numerous deep ravines, and studded with rugged tors.

The road through this overshadowed labyrinth is continually mounting and descending the slippery banks of the countless torrents that intersect it, twisting and winding in every direction; and, on gaining the heart of the forest, the path is crossed and cut up by such numbers of timber-tracks, and is screened from the sun’s cheering rays by so impervious a covering, that the difficulty of choosing a path amongst the many which presented themselves was yet further increased by that of determining the point of the compass towards which they were respectively directed.

The guide we had brought with us, though pretending to be thoroughly acquainted with every pathway in the forest, was evidently as much at a nonplus as we ourselves were; and his muttered malditos and carajos, like the rolling of distant thunder, announced the coming of a storm. At length it burst forth: the track he had selected, after various windings, led only to the stump of a venerable oak. Never was mortal in a more towering passion; he snatched his hat from his head, threw it on the ground, and stamped upon it, swearing by, or at—for we could hardly distinguish which—all the saints in the calendar. After enjoying this scene for some time, we spread ourselves in different directions in search of the beaten track; and, at last, a swineherd, attracted by our calls to each other, came to our deliverance; and our guide, after bestowing sundry malditos upon the wood, the torrents, the timber-tracks, and those who made them, resumed his wonted state of composure, assuring us, that there was some accursed hobgoblin in this hi-de-puta forest, who took delight in leading good Catholics astray; that during the war an entire regiment, misled by some such malhechor,[16] had been obliged to bivouac there for the night, to the great detriment of his very Catholic Majesty’s service.

Soon after this little adventure we reached a solitary house, called the Venta de Montera, which is something more than half way between Ubrique and Ximena; i.e. eleven miles from the former, and nine from the latter. A little way beyond this the road reaches an elevated chain of hills, that separates the rivers Sogarganta and Guadiaro; the summit of which being rather a succession of peaks than a continuous ridge, occasions the track to be conducted sometimes along the edge of one valley, sometimes of the other. The mountain falls very ruggedly to the first-named river, but in one magnificent sweep to the Guadiaro.

The views on both sides are extremely fine; that on the left hand embraces Gibraltar’s cloud-wrapped peaks, the mirror-like Mediterranean, Spain’s prison-fortress of Ceuta, and the blue mountains of Mauritanía; the other looks over the silvery current of the Sogarganta, winding amidst the roots of a peculiarly wild and wooded country, and towards the rock-built little fortress of Castellar.

The road continues winding along this elevated heather-clad ridge for four miles, and then descends by rapid zig-zags towards Ximena.

The town lies crouching under the shelter of a rocky ledge, that, detached from the rest of the sierra, and crowned with the ruined towers of an ancient castle, forms a bold and very picturesque feature in the view, looking southward. The town is nearly a mile in length, and consists principally of two long narrow streets, one extending from north to south quite through it, the other leading up to the castle. The rest of the callejones[17] are disposed in steps up the steep side of the impending hill, and can be reached only on foot.

The old castle—in great part Roman, but the superstructure Moorish—is accessible only on the side of the town (east), and in former days must have been almost impregnable. The narrow-ridged ledge whereon it stands has been levelled, as far as was practicable, to give capacity to this citadel, which is 400 yards in length, and varies in breadth from 50 to 80. It rises gently, so as to form two hummocks at its extremities; and the narrowest part of the inclosure being towards the centre, it has very much the form of a calabash.

A strongly built circular tower, mounting artillery, and enclosed by an irregular loop-holed work of some strength, occupies the southern peak of the ridge; and a fort of more modern structure, but feeble profile, covers that in which it terminates to the north. An irregularly indented wall, or in some places scarped rock, connects these two retrenched works along the eastern side of the ridge; but, in the opposite direction, the cliff falls precipitously to the river Sogarganta; rendering any artificial defences, beyond a slight parapet wall, quite superfluous.

Numerous vaulted tanks and magazines afforded security to the ammunition and provisions of the isolated little citadel; but they are now in a wretched state, as well as the outworks generally; for the fortress was partially blown up by Ballasteros, (A.D. 1811) upon his abandoning it, on the approach of the French, to seek a surer protection under the guns of Gibraltar.

In exploring the ruined tanks of this old Moorish fortress, chance directed our footsteps to an unfrequented spot where some smugglers were in treaty with a revenue guarda, touching the amount of bribe to be given for his connivance at the entry of sundry mule loads of contraband goods into the town on the following night.

We did not pry so curiously into the proceedings of the contracting parties, as to ascertain the precise sum demanded by this faithful servant of the crown for the purchase of his acquiescence to the proposed arrangement, but, from the elevated shoulders, outstretched arms, and down-stretched mouth, of one of the negociators, it was evident that the demand was considered unconscionable; and the roguish countenance of the custom-house shark as clearly expressed in reply, “But do you count for nothing the sacrifice of principle I make?”

From the ruined ramparts of Fort Ballasteros (the name by which the northern retrenched work of the fortress is distinguished) the view looking south is remarkably fine. The keep of the ancient castle, enclosed by its comparatively modern outworks, and occupying the extreme point of the narrow rocky ledge whereon we were perched, stands boldly out from the adjacent mountains; whilst, deep sunk below, the tortuous Sogarganta may be traced for miles, wending its way towards the Almoraima forest. Above this rise the two remarkable headlands of Gibraltar and Ceuta; the glassy waterline between them marking the separation of Europe and Africa.

That Ximena was once a place of importance there can be no doubt, since it gave the title of King to Abou Melic, son of the Emperor of Fez; and that it was a Roman station (though the name is lost,) is likewise sufficiently proved, as well by the walls of the castle, as by various inscriptions which have been discovered in the vicinity. At the present day, it is a poor and inconsiderable town, whose inhabitants, amounting to about 8000, are chiefly employed in smuggling and agriculture.

On issuing from the town, the road to Gibraltar crosses the Sogarganta, having on its left bank, and directly under the precipitous southern cliff of the castle rock, the ruins of an immense building, erected some sixty years back, for the purpose of casting shot for the siege of Gibraltar!

The distance from Ximena to the English fortress is 25 miles. The road was, in times past, practicable for carriages throughout; and even now is tolerably good, though the bridges are not in a state to drive over. It is conducted along the right bank of the Sogarganta; at six miles, is joined by a road that winds down from the little town of Castellar on the right; and, at eight, enters the Almoraima forest by the “Lion’s Mouth,” of which mention has already been made. The river, repelled by the steep brakes of the forest, winds away to the eastward to seek the Guadiaro and Genil.

Here I will take a temporary leave of my readers, to seek a night’s lodging at a cottage in the neighbourhood, which, being frequented by some friends and myself in the shooting season, we knew could furnish us with clean beds and a gazpacho.

DEPARTURE FOR CADIZ—ROAD ROUND THE BAY OF GIBRALTAR—ALGECIRAS—SANDY BAY—GUALMESI—TARIFA—ITS FOUNDATION—ERROR OF MARIANA IN SUPPOSING IT TO BE CARTEIA—BATTLE OF EL SALADO—MISTAKE OF LA MARTINIERE CONCERNING IT—ITINERARY OF ANTONINUS FROM CARTEIA TO GADES VERIFIED—CONTINUATION OF JOURNEY—VENTAS OF TAVILLA AND RETIN—VEJER—CONIL—SPANISH METHOD OF EXTRACTING GOOD FROM EVIL—TUNNY FISHERY—BARROSA—FIELD OF BATTLE—CHICLANA—ROAD TO CADIZ—PUENTE ZUAZO—SAN FERNANDO—TEMPLE OF HERCULES—CASTLE OF SANTI PETRI—ITS IMPORTANCE TO CADIZ.

HOPING that the taste of my readers, like my own, leads them to prefer the motion of a horse to that of a ship, the chance of being robbed to that of being sea-sick, and the savoury smell of an olla to the greasy odour of a steam engine, I purpose in my next excursion to conduct them to Cadiz by the rude pathway practised along the rocky shore of the Straits of Gibraltar, and thence, “inter æstuaria Bætis,” to Seville, instead of proceeding to those places by the more rapid and now generally adopted means of fire and water. From the last named “fair city” we will return homewards by another passage through the mountains of Ronda.

To authorise me—a mere scribbler of notes and journals—to assume the plural we, that gives a Delphic importance to one’s opinions (but under whose shelter I gladly seek to avoid the charge of egotism), I must state that a friend bore me company on this occasion; our two servants, with well stuffed saddle-bags and alforjas, “bringing up the rear.”

Proceeding along the margin of the bay of Gibraltar, leaving successively behind us the ruins of Fort St. Philip, which a few years since gave security to the right flank of the lines drawn across the Isthmus in front of the British fortress; the crumbling tower of Cartagena, or Recadillo, which, during the seven centuries of Moslem sway, served as an atalaya, or beacon, to convey intelligence along the coast between Algeciras and Malaga; and, lastly, the scattered fragments of the yet more ancient city of Carteia, we arrive at the river Guadaranque.

The stream is so deep as to render a ferry-boat necessary. That in use is of a most uncouth kind, and so low waisted that “Almanzor,” who was ever prone to gad amongst the Spanish lady Rosinantes, could not be deterred from showing his gallantry to some that were collected on the opposite side of the river, by leaping “clean out” of the boat before it was half way over. Fortunately, we had passed the deepest part of the stream, so that I escaped with a foot-bath only.

The road keeps close to the shore for about a mile and a half, when it reaches the river Palmones, which is crossed by a similarly ill-contrived ferry. From hence to Algeciras is three miles, the first along the sea-beach, the remainder by a carriage-road, conducted some little distance inland to avoid the various rugged promontories which now begin to indent the coast, and to dash back in angry foam the hitherto gently received caresses of the flowing tide.

The total distance from Gibraltar to Algeciras, following the sea-shore, is nine English miles; but straight across the bay it is barely five.

Algeciras, supposed to be the Tingentera of the ancients, and by some the Julia Traducta of the Romans, received its present name from the Moors—Al chazira, the island. In the days of the Moslem domination, it became a place of great strength and importance; and when the power of the Moors of Spain began to wane, was one of the towns ceded to the Emperor of Fez, to form a kingdom for his son, Abou Melic, in the hope of presenting a barrier that would check the alarming progress of the Christian arms. From that time it became a constant object of contention, and endured many sieges. The most memorable was in 1342-4, during which cannon were first brought into use by its defenders. It, nevertheless, fell to the irresistible Alfonso XI., after a siege of twenty months.

At that period, the town stood on the right bank of the little river Miel (instead of on the left, as at present), where traces of its walls are yet to be seen; but its fortifications having shortly afterwards been razed to the ground by the Moors, the place fell to decay, and the present town was built so late as in 1760. It is unprotected by walls, but is sheltered from attack on the sea-side by a rocky little island, distant 800 yards from the shore. This island is crowned with batteries of heavy ordnance, and has, on more occasions than one, been found an “ugly customer” to deal with. The anchorage is to the north of the island, and directly in front of the town.

The streets of Algeciras are wide and regularly built, remarkably well paved, and lined with good houses; but it is a sun-burnt place, without a tree to shelter, or a drain to purify it. Being the port of communication between Spain and her presidario, Ceuta, as well as the military seat of government of the Campo de Gibraltar, it is a place of some bustle, and carries on a thriving trade, by means of felucas and other small craft, with the British fortress. The population may be reckoned at 8,000 souls, exclusive of a garrison of from twelve to fifteen hundred men.

The Spaniards call the rock of Gibraltar el cuerpo muerto,[18] from its resemblance to a corpse; and, viewed from Algeciras, it certainly does look something like a human figure laid upon its back, the northernmost pinnacle forming the head, the swelling ridge between that and the signal tower, the chest and belly, and the point occupied by O’Hara’s tower the bend of the knees.

The direct road from Algeciras to Cadiz crosses the most elevated pass in the wooded mountains that rise at the back of the town, and, from its excessive asperity, is called “The Trocha,” the word itself signifying a bad mountain road. The distance by this route is sixty-two miles; by Tarifa it is about a league more, and this latter road is not much better than the other, though over a far lower tract of country.

On quitting the town, the road, having crossed the river Miel, and passed over the site of “Old Algeciras,” situated on its right bank, edges away from the coast, and, in about a mile, reaches a hill, whence an old tower is seen standing on a rocky promontory; which, jutting some considerable distance into the sea, forms the northern boundary of a deep and well sheltered bay. The Spanish name for this bight is La Ensenada de Getares; but by us, on account of the high beach of white sand that edges it, it is called “Sandy bay.” It strikes me this must be the Portus albus of Antoninus’s Itinerary, since its distance from Carteia corresponds exactly with that therein specified, and renders the rest of the route to Gades intelligible, which, otherwise, it certainly is not. But more of this hereafter.

Within two miles of Algeciras the road crosses two mountain torrents, the latter of which, called El Rio Picaro[19] (I presume from its occasional treacherous rise), discharges itself into the bay of Getares. Thenceforth, the track becomes more rugged, and ascends towards a pass, (El puerto del Cabrito) which connects the Sierra Santa Ana on the right with a range of hills that, rising to the south, and closing the view in that direction, shoots its gnarled roots into the Straits of Gibraltar.

The views from the pass are very fine—that to the eastward, looking over the lake-like Mediterranean and towards the snowy sierras of Granada; the other, down upon the rough features of the Spanish shore, and towards the yet more rugged mountains of Africa; the still distant Atlantic stretching away to the left. The former view is shut out immediately on crossing the ridge: but the other, undergoing pleasing varieties as one proceeds, continues very fine all the way to Tarifa.

The road is now very bad, being conducted across the numerous rough ramifications of the mountains on the right hand, midway between their summits and the sea. At about seven miles from Algeciras it reaches the secluded valley of Gualmesi, or Guadalmesi, celebrated for the crystaline clearness of its springs, and the high flavour of its oranges; and, crossing the stream, whence the romantic dell takes its name, directs itself towards the sea-shore, continuing along it the rest of the way to Tarifa; which place is distant twelve miles from Algeciras.

The stratification of the rocks along this coast is very remarkable: the flat shelving ledges that border it running so regularly in parallel lines, nearly east and west, as to have all the appearance of artificial moles for sheltering vessels. It is on the contrary, however, an extremely dangerous shore to approach.

The old Moorish battlements of Tarifa abut against the rocky cliff that bounds the coast; stretching thence to the westward, along, but about 50 yards from, the sea. It is not necessary, therefore, to enter the fortress; indeed, one makes a considerable détour in doing so; but curiosity will naturally lead all Englishmen—who have the opportunity—to visit the walls so gallantly defended by a handful of their countrymen during the late war; and those who cannot do so may not object to read a somewhat minute description of them.

The town closes the mouth of a valley, bound by two long but slightly marked moles, protruded from a mountain range some miles distant to the north; the easternmost of which terminates abruptly along the sea-shore. The walls extend partly up both these hills; but not far enough to save the town from being looked into, and completely commanded, within a very short distance. Their general lines form a quadrangular figure, about 600 yards square; but a kind of horn work projects from the N.E. angle, furnishing the only good flanking fire that the fortress can boast of along its north front. Every where else the walls, which are only four feet and a half thick, are flanked by square towers, themselves hardly solid enough to bear the weight of artillery, much less its blows.

At the S.W. angle, but within the enceinte of the fortress, and looking seawards, there is a small castle, or citadel, the alcazar of its Moorish governors; and immediately under its machicoulated battlements is one of the three gateways of the town. The two others are towards the centre of its western and northern fronts.

In the attack of 1811, the French made their approaches against the north front of the town, and effected a breach towards its centre, in the very lowest part of the bed of the valley; thus most completely “taking the bull by the horns;” (and Tarifa bulls are not to be trifled with—as every Spanish picador knows,) since the approach to it was swept by the fire of the projecting horn-work I have before mentioned.

When the breach was repaired, a marble tablet was inserted in the wall, bearing a modest inscription in Latin, which states that “this part of the wall, destroyed by the besieging French, was re-built by the British defenders in November, 1813.”

When the French again attacked the fortress, in 1823, profiting by past experience, they established their breaching batteries in a large convent, distant about 200 yards from the walls on the west front of the town; and, favouring their assault by a feigned attack on the gate in its south wall, they carried the place with scarcely any loss.

The streets of Tarifa are narrow, dark, and crooked; and, excepting that they are clean, are in every respect Moorish. The inhabitants are rude in speech and manners, and amount to about 8000.

From the S.E. salient angle of the town, a sandy isthmus juts about a thousand yards into the sea, and is connected by a narrow artificial causeway with a rocky peninsula, or island, as it is more generally termed, that stretches yet 700 or 800 yards further into the Straits of Gibraltar. This is the most southerly point of Europe, being in latitude 30° 0’ 56", which is nearly six miles to the south of Europa Point.

The island is of a circular form, and towards the sea is merely defended by three open batteries, armed en barbette; but to the land side, it presents a bastioned front, that sweeps the causeway with a most formidable fire. A lighthouse stands at the extreme point of the island, which also contains a casemated barrack for troops, and some remarkable old tanks, perhaps of a date much prior to the arrival of the Saracens.

The foundation of the town of Tarifa is usually ascribed to Tarik Aben Zaide, the first Mohammedan invader of Spain; who probably, previous to crossing the Straits, had marked the island as offering a favourable landing-place, as well as a secure depôt for his stores, and a safe refuge in the event of a repulse. Mariana, however, imagined, that Tartessus, or Carteia—which he considered the same place—stood upon this spot; and, under this persuasion, he speaks of the admiral of the Pompeian faction retiring there, after his action with Cæsar’s fleet, and drawing a chain across the mouth of the port to protect his vessels; a circumstance which alone proves that Carteia was not Tarifa; since it must be evident to any one who has examined the coast attentively, that no port could possibly have existed there, which could have afforded shelter to a large fleet, and been closed by drawing a chain across its mouth.

Others, again, suppose Tarifa to occupy the site of Mellaria. But I rather incline to the opinion of those who consider it doubtful whether any Roman town stood upon the spot; an opinion for which I think I shall hereafter be able to assign sufficient reason.

As Tarifa was the field wherein the Mohammedan invaders of Spain obtained their first success, so, six centuries after, did it become the scene of one of their most humiliating defeats; the battle of the Salado, gained A.D. 1340, by Alphonso XI., of Castile, having inflicted a blow upon them, from the effects of which they never recovered. Four crowned heads were engaged in that sanguinary conflict—the King of Portugal, as the ally of the Castillian hero; Jusuf, King of Granada; and Abu Jacoob, Emperor of Morocco. The last-named, according to the Spanish historians, had crossed over from Africa, with an army of nearly half a million of men, to avenge the death of his son, Abou Melic; killed the preceding year at the battle of Arcos.

The little river, which gave its name to that important battle gained by the Christian army on its banks, winds through a plain to the westward of Tarifa, crossing the road to Cadiz, at about two miles from the town.[20] The valley is about three miles across, and extends a considerable distance inland. It is watered by several mountain streams that fall into the Salado. That rivulet is the last which is met with, and is crossed by a long wooden bridge on five stone piers.

The term Salado is of very common occurrence amongst the names of the rivers of the south of Spain; though in most cases it is used rather as a term signifying a water-course, than as the name of the rivulet: thus El Salado de Moron is a stream issuing from the mountains in the vicinity of the town of Moron; El Salado de Porcuna is a torrent that washes the walls of Porcuna; and so with the rest. As, however, the word in Spanish signifies salt, (used adjectively) it has led to many mistakes, and occasioned much perplexity in determining the course of the river Salsus, mentioned so frequently by Hirtius; but to which, in point of fact, the word Salado has no reference whatever, being applied to numerous streams that are perfectly free from salt.

On the other hand, it might naturally be supposed that the word Salido (the past participle of the verb Salir, to issue) would have been used if intended to signify a source or stream issuing from the mountains.

It seems to me, therefore, that the word Salado must be a derivation from the Arabic Sāl, a water-course in a valley; which, differing so little in sound from Salido, continued to be used after the expulsion of the Moors; until at length, its derivation being lost, it came to be considered as signifying what the word actually means in Spanish, viz. impregnated with salt.

At the western extremity of the plain, watered by the Salado de Tarifa, a barren Sierra terminates precipitously along the coast, leaving but a narrow space between its foot and the sea, for the passage of the road to Cadiz. Under shelter of the eastern side of this Sierra, standing in the plain, but closing the little Thermopylæ, I think we may place the Roman town of Mellaría,[21] eighteen miles from Carteia, and six from Belone Claudia, according to the Itinerary of Antoninus; and mentioned by Strabo as a place famous for curing fish.

Tarifa, which, as I have said before, is supposed by some authors to be on the site of Mellaría, is in the first place rather too near Calpe Carteia to accord with that supposition; and in the next, it is far too distant from Belon; the site of which is well established by numerous ruins visible to this day, at a despoblado,[22] called Bolonia.

It may be objected, on the other hand, that the position which I suppose Mellaría to have occupied, is as much too far removed from Carteia, as Tarifa is too near it: and following the present road, it certainly is so. But there is no reason to take for granted that the ancient military way followed this line; on the contrary, as the Romans rather preferred straight to circuitous roads, we may suppose that, as soon as the nature of the country admitted of it, they carried their road away from the coast, to avoid the promontory running into the sea at Tarifa. Now, an opportunity for them to do this presented itself on arriving at the valley of Gualmesi, from whence a road might very well have been carried direct to the spot that I assign for the position of Mellaría; which road, by saving two miles of the circuitous route by Tarifa, would fix Mellaría at the prescribed distance from Carteia, and also bring it (very nearly) within the number of miles from Belon, specified in the Roman Itinerary, viz. six; whereas, if Mellaría stood where Tarifa now does, the distance would be nearly ten.

The city of Belon appears to have slipped bodily from the side of the mountain on which it was built (probably the result of an earthquake), as its ruins may be distinctly seen when the tide is out and the water calm, stretching some distance into the Atlantic. Vestiges of an aqueduct may also be traced for nearly a league along the coast, by means of which the town was supplied with water from a spring that rises near Cape Palomo, the southernmost point of the same Sierra under which Belon was situated.

In following out the Itinerary of Antoninus—according to which the total distance from Calpe to Gades is made seventy-six miles[23]—the next place mentioned after Belon Claudia is Besippone, distant twelve miles. This place, it appears to me, must have stood on the coast a little way beyond the river Barbate; and not at Vejer, (which is several miles inland) as some have supposed; for the distance from the ruins of Bolonia to that town far exceeds that specified in the Itinerary.

Vejer (or Beger, as it is indifferently written) may probably be where a Roman town called Besaro stood, of which Besippo was the port; the latter only having been noticed in the Itinerary from it being situated on the direct military route from Carteia to Gades; the former by Pliny,[24] as being a place of importance within the Conventus Gaditani.

From Besippone to Mergablo—the next station of the Itinerary—is six miles; and at that distance from the spot where I suppose the first of those places to have stood, there is a very ancient tower on the sea side, (to the westward of Cape Trafalgar) from which an old, apparently Roman, paved road, now serving no purpose whatever, leads for several miles into the country. From this tower to Cadiz—crossing the Santi Petri river at its mouth—the distance exceeds but little twenty-four miles; the number given in the Itinerary.

The distances I have thus laid down agree pretty well throughout with those marked on the Roman military way; which, it may be supposed, were not very exactly measured, since the fractions of miles have in every case been omitted. The only objection which can be urged to my measurements is, that they make the Roman miles too long. Having, however, taken the Olympic stadium (in this instance) as my standard, of which there are but 600 to a degree of the Meridian, or seventy-five Roman miles; and as my measurements, even with it, are still rather short, the reply is very simple, viz. that the adoption of any smaller scale would but increase the error.

From the spot where I suppose Mellaría to have stood—which is marked by a little chapel standing on a detached pinnacle of the Sierra de Enmedio, overhanging the sea—the distance to the Rio Baqueros is two miles; the road keeping along a flat and narrow strip of land, between the foot of the mountain and the sea.

The coast now trends to the south west, a high wooded mountain, distinguished by the name of the Sierra de San Mateo, stretching some way into the sea, and forming the steep sandy cape of Paloma, a league on the western side of which are the ruins of Belon.

The road to Cadiz, however, leaves the sea-shore to seek a more level country, and, inclining slightly to the north, keeping up the Val de Baqueros for five miles, reaches a pass between the mountains of San Mateo and Enmedio.

The valley is very wild and beautiful. Laurustinus, arbutus, oleander, and rhododendron are scattered profusely over the bed of the torrent that rushes down it; and the bounding mountains are richly clothed with forest trees.

From the pass an extensive view is obtained of the wide plain of Vejer, and laguna de la Janda in its centre. Descending for two miles and a half,—the double-peaked Sierra de la Plata being now on the left hand, and that of Fachenas, studded with water-mills, on the right—the road reaches the eastern extremity of the above-named plain, where the direct road from Algeciras to Cadiz falls in, and that of Medina Sidonia branches off to the right. The Cadiz route here inclines again to the westward, and, in three miles, reaches the Venta de Tavilla.

From hence two roads present themselves for continuing the journey; one proceeding along the edge of the plain; the other keeping to the left, and making a slight détour by the Sierra de Retin; and when the plain is flooded, it is necessary to take this latter route. Let those who find themselves in this predicament avoid making the solitary hovel, called the Venta de Retin, their resting-place for the night, as I was once obliged to do; for, unless they are partial to a guard bed, and to go to it supperless, they will not meet with accommodation and entertainment to their liking.

We will return, however, to the Venta de Tabilla, which is a fraction of a degree better than that of Retin. From thence the distance to Vejer is fourteen miles. The first two pass over a gently swelling country, planted with corn; the next six along the low wooded hills bordering the laguna de la Janda; the remainder over a hilly, and partially wooded tract, whence the sea is again visible at some miles distance on the left.

In winter the greater part of the plain of Vejer is covered with water, there being no outlet for the Laguna; which, besides being the reservoir for all the rain that falls on the surrounding hills, is fed by several considerable streams.

A project to drain the lake was entertained some years ago; but, like all other Spanish projects, it failed, after an abortive trial. In its present state, therefore, the whole surface of the plain is available only for pasture; and numerous herds are subsisted on it. The gentle slopes bounding it, being secure from inundation, are planted with corn.

Vejer is situated on the northern extremity of a bare mountain ridge, that stretches inland from the coast about five miles, and terminates in a stupendous precipice along the right bank of the river Barbate. Towards the sea, however, it slopes more gradually, forming the forked headland, for ever celebrated in history, called Cape Trafalgar.

When arrived within half a mile of the lofty cliff whereon the town stands, the road enters a narrow gorge, by which the Barbate escapes to the ocean; this part of its course offering a remarkable contrast to the rest, which is through an extensive flat.

A stone bridge of three curiously constructed arches, said to be Roman, gives a passage over the stream; and a venta is situated on the right bank, immediately under the town; the houses of which may be seen edging the precipice, at a height of five or six hundred feet above the river.

The road to Cadiz, and consequently all others,—it being the most southerly,—avoids the ascent to Vejer, which is very steep, and so circuitous as to occupy fully half an hour. But the place is well worth a visit, if only for the sake of the view from the church steeple, which is very extensive and beautiful; and taken altogether, it is a much better town than could be expected, considering its truly out-of-the-way situation. That it was a Roman station, its position alone sufficiently proves; but whether it be the Besaro, or Belippo, or even Besippo of Pliny, seems doubtful.

It occupies a tolerably level space; though bounded on three sides by precipices, and is consequently still a very defensible post, notwithstanding its walls are all destroyed. The streets are narrow, but clean and well paved; and the place contains many good houses, and several large convents. The inns, however, are such wretched places, that on one occasion, when I passed a night there, I had to seek a resting-place in a private house.

The Barbate is navigable for large barges up to the bridge; but the difficulty of access to the town prevents its carrying on much trade. The population amounts to about 6,000 souls.

There is a delightful walk down a wooded ravine on the western side of the town, by which the road to Cadiz and the valley of the Barbate may be regained quicker than by retracing our footsteps to the Venta. Of this latter I feel bound to say—after much experience—that there is not a better halting-place between Cadiz and Gibraltar; albeit, many stories are told of robberies committed even within its very walls. Let the traveller take care, therefore, to show his pistols to mine host, and to lock his bedroom door.

We resumed our journey with the dawn. The road keeps for nearly a mile along the narrow, flat strip between the bank of the river, and the high cliff whereon the town is perched. The gorge then terminates, and an open country permits the roads to the different neighbouring places to branch off in their respective directions. From hence to Medina Sidonia is thirteen miles; to Alcalà de los Gazules, twenty; and to Chiclana—whither we were bound—fifteen;—but, leaving these three roads on the right, we proceeded by a rather more circuitous route to the last mentioned place, by Conil and Barrosa.

The distance from Vejer to Conil is nine miles; the country undulated and uninteresting. Conil is a large fishing town, containing a swarming population of 8,000 souls. The smell of the houses where the tunny fish (here taken in great abundance) are cut up and cured, extends inland for several miles; but the inhabitants consider it very wholesome; and to my animadversive remarks on the filth and effluvium of the place itself, answer was made, “no hay epidemia aqui;”[25]—quite a sufficient excuse, according to their ideas, for submitting to live the life of hogs.

We arrived just as the fishermen had enclosed a shoal of Tunny with their nets; so, putting up our horses, we waited to see the result of their labours. The whole process is very interesting. The Tunny can be discovered when at a very considerable distance from the land; as they arrive in immense shoals, and cause a ripple on the surface of the water, like that occasioned by a light puff of wind on a calm day. Men are, therefore, stationed in the different watch towers along the coast, to look out for them, and, immediately on perceiving a shoal, they make signals to the fishermen, indicating the direction, distance, &c. Boats are forthwith put to sea, and the fish are surrounded with a net of immense size, but very fine texture, which is gradually hauled towards the shore.

The tunny, coming in contact with this net, become alarmed, and make off from it in the only direction left open to them. The boats follow, and draw the net in, until the space in which the fish are confined is sufficiently small to allow a second net, of great strength, to circumscribe the first; which is then withdrawn. The tunny, although very powerful, (being nearly the size and very much the shape of a porpoise) have thus far been very quiet, seeking only to escape under the net; and have hardly been perceptible to the spectators on the beach. But, on drawing in the new net, and getting into shallow water, their danger gives them the courage of despair, and furious are their struggles to escape from their hempen prison.

The scene now becomes very animated. When the draught is heavy—as it was in this instance—and there is a possibility of the net being injured, and of the fish escaping if it be drawn at once to land, the fishermen arm themselves with harpoons, or stakes, having iron hooks at the end, and rush into the sea whilst the net is yet a considerable distance from the shore, surrounding it, and shouting with all their might to frighten the fish into shallow water, when they become comparatively powerless.

In completing the investment of their prey, some of the fishermen are obliged even to swim to the outer extremity of the net, where, holding on by the floats with one hand, they strike, with singular dexterity, such fish as approach the edge, in the hope of effecting their escape, with a short harpoon held in the other. The men in the boats, at the same time, keep up a continual splashing with their oars, to deter the tunny from attempting to leap over the hempen enclosure; which, nevertheless, many succeed in doing, amidst volleys of “Carajos!”

The fish are thus killed in the water, and then drawn in triumph on shore. They are allowed to bleed very freely; and the entrails, roes, livers, and eyes, are immediately cut out, being perquisites of different authorities.

The flesh is salted, and exported in great quantities to Catalonia, Valencia, and the northern provinces of the kingdom. A small quantity of oil is extracted from the bones.