A FLOATING HOME

·

CYRIL IONIDES · J. B. ATKINS

ARNOLD BENNETT

Project Gutenberg's A Floating Home, by Cyril Ionides and J. B. Atkins

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Floating Home

Author: Cyril Ionides

J. B. Atkins

Illustrator: Arnold Bennett

Release Date: February 13, 2013 [EBook #42091]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A FLOATING HOME ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

A FLOATING HOME

·

CYRIL IONIDES · J. B. ATKINS

ARNOLD BENNETT

A FLOATING HOME

A BARGE PASSING THE MAPLIN LIGHT

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1918

All rights reserved

To

THE MATE

The authors owe to their readers an explanation of the manner of their collaboration. The owner of the Thames sailing barge, of which the history as a habitation is written in this book, is Mr. Cyril Ionides. ‘I’ throughout the narrative is Mr. Cyril Ionides; the ‘Mate’ is Mrs. Cyril Ionides; the children are their children. Yet the other author, Mr. J. B. Atkins, was so closely associated with the events recorded—sharing with Mr. Ionides the counsels and discussions that ended in the purchase of the barge, prosecuting in his company friendships with barge skippers, and studying with him the Essex dialect, which nowhere has more character than in the mouths of Essex seafaring men—that it was not practicable for the book to be written except in collaboration. The authors share, moreover, an intense admiration for the Thames sailing barges, to which, so far as they know, justice has never been done in writing. Mr. Atkins, however, felt that it would be unnecessary, if not impertinent, for him to assume any personal shape in the narrative when there was little enough space for the more relevant and informing characters of Sam Prawle, Elijah Wadely, and their like.

The book aims at three things: (1) It tells how the problem of poverty—poverty judged by the standard of one who wished to give his sons a Public School education on an insufficient income—was solved by living afloat and avoiding the payment of rent and rates. (2) It offers a tribute of praise to the incomparable barge skippers who navigate the busiest of waterways, with the smallest crews (unless the cutter barges of Holland provide an exception) that anywhere in the world manage so great a spread of canvas. Londoners are aware that the most characteristic vessels of their river are ‘picturesque.’ Beyond that their knowledge or their applause does not seem to go. It is hoped that this book will tell them something new about a life at their feet, of the details of which they have too long been ignorant. (3) It is a study in dialect. It was impossible to grow in intimacy with the Essex skippers of barges without examining with careful attention the dialect that persists with a surprising flavour within a short radius of London, where one would expect everything of the sort—particularly in the va-et-vient of river life—to be assimilated or absorbed.

As to (1) and (3) something more may be said.

One of the authors (J. B. A.) published in the Spectator before the war a brief account of Mr. Cyril Ionides’ floating home, and was immediately beset by so many inquiries for more precise information that he perceived that a book on the subject—a practical and complete answer to the questions—was required. Neither of the authors is under any illusion as to the determination of those who have made such inquiries. Most of the inquirers no doubt are people who will not go further with the idea than to play with it. But that need not matter. The idea is a very pleasant one to play with. The few who care to proceed will find enough information in this book for their guidance. The items of expenditure, the method of transforming the barge from a dirty trading vessel into an agreeable home, a diagram of the interior arrangements, are all given. The castle in Spain has actually been built, and people are living in it.

Here is a scheme of life for which romantic is perhaps neither too strong a word nor one incapable of some freshness of meaning. The idea is available for anyone with enough resolution. Of course, not every amateur seaman would care to undertake the mastership of so large a vessel as a Thames sailing barge, but that natural hesitation need be no hindrance. The owner would want no crew when safely berthed for the winter; and in the summer a professional skipper and his mate (only two hands are required) would sail him about with at least as much satisfaction to him as is obtained by the owners of large yachts carrying bloated crews.

If he is a ‘bad sailor’ he could get more pleasure from a barge than from an ordinary yacht of greater draught. The barge can choose her water; she can run into the smooth places that lie between the banks of the complicated Thames estuary. She can thread the Essex and Suffolk tidal rivers; the Crouch, the Roach, the Blackwater, the Colne, the Stour, the Orwell, the Deben, the Aide, are all open to her, and are delightfully wild and unspoiled; she can sit upright upon a sandbank till a blow is over. Many people who could afford yachting and are drawn to it persistently think that it is not for them, because they are ‘bad sailors.’ If they tried barging on the most broken coast in England—say between Lowestoft and Whitstable—they would be very pleasantly undeceived, unless indeed their case is hopeless. This book, however, is not written to recruit the world of yachtsmen, but to show how a home—a floating home on the sea for winter as well as summer, not a tame houseboat—and a yacht may be combined at a saving of cost to the householder.

And by those whose heart is equal to the adventure this cure for the modern ‘cost of living’ will not by any means be found an uncomfortable makeshift, a disagreeable sacrifice by a conscientious father of a family. A barge is not a poky hole. The barge described in this book, though one is not conscious of being cramped inside her, is only a ninety tonner. It would be easy to acquire a barge of a hundred and twenty tons, and such a vessel could still be sailed by two hands. The saloon in Mr. Ionides’ barge is as large as many drawing-rooms in London flats which are rented at £150 a year. In a small London flat which was not designed for inhabitants ‘cooped in a wingèd sea-girt citadel’ (though it might have been better if it had been) there is little thought of saving space. In a vessel, one of the primary objects of the designer is to save space. Sailors in their habits act on the same principle. The success that has been achieved by both architects and seamen is almost incredible. No one who has lived for any length of time in a vessel has ever been able to rid himself of the grateful sense that he has more room than he could have expected, and certainly more than ever appeared from the outside.

Nor do the points in favour of a vessel as a house end there. A ship is cool in the summer and warm in the winter. In the summer you have the sea breezes, which can be directed or diverted by awnings and windows as you like. In the winter a ship is easily warmed and there are no draughts. Although a vessel is farther removed from the world than a flat, your contact with the world is paradoxically closer. If you go downstairs from your flat you must dress yourself for the street. The very man who works the lift, and mediates between you and the external world, expects it of you. But from your comfortable cabin on board ship to the deck, which gives you a platform in touch with all that is outside, there are but half a dozen steps up the companion. And yet, in touch with the world, you are still in your own territory. You have not, as a matter of habit, changed your clothes.

A sea-going vessel is a real home, a property with privileges attached, and a solution of a difficulty. We hear much praise of caravanning—a most agreeable pastime for those who prefer the rumble of wheels to the wash of the tide or the humming of wind in the rigging. But is it a solution of anything? It has not been stated that it is. Let any receiver of an exiguous salary, who trudges across London Bridge daily between his train and his office, not assume finally that a more romantic way of life than his is impossible. Let him lean for a few moments over the bridge, watch the business of the Pool, and ask himself whether he sees in one of the sailing barges his ideal home and the remedy for him of that tormenting family budget of which the balance is always just on the wrong side.

Life in a barge brings you acquainted with bargees. They are your natural neighbours. The dialect of those who belong to Essex has been reproduced in this book as faithfully as possible. If certain words such as ‘wonderful’ (very) and ‘old’ occur very frequently, it is because the authors have written down yarns and phrases as they heard them, and not with an eye to introducing what might seem a more credible variety of language. It is said that dialects are everywhere yielding to a universal system of education. In the opinion of the authors the surrender is much less extensive than is supposed. Some people have no ear for dialect, and are capable of hearing it without knowing that it is being talked. The users of local phrases, for their part, are often shy, and if asked to repeat an unusual word will pretend to be strangers to it, or, more unobtrusively, substitute another word and continue apace into a region of greater safety. The authors, however, have had the good fortune to be on such terms with some men of Essex that they have been able to discuss dialect words with them without embarrassment. It is hoped that the glossary at the end of the book will be found a useful collection by those who are interested in the subject. Some of the words, which have become familiar to the authors, are not mentioned in any dialect dictionary. Although the Essex dialect has persisted, it has not persisted in an immutable form. So far as the authors may trust their ears, they are certain that the pronunciation of the word ‘old’ (which is used in nearly every sentence by some persons) is always either ’ould’ or ‘owd.’ But if one looks at the well-known Essex dialect poem ‘John Noakes and Mary Styles: An Essex Calf’s Visit to Tiptree Races,’ by Charles Clark, of Great Totham Hall (1839), one sees that ‘old’ used to be pronounced ‘oad.’ In the same poem ‘something’ is written ‘suffin’,’ though the authors of this book, on the strength of their experience, have felt bound to write it ‘suthen.’ In Essex to-day ‘it’ at the end of a sentence, and sometimes elsewhere, is pronounced ‘ut’—in the Irish manner. Some words are pronounced in such a way as to encourage an easy verdict that the Essex accent is Cockney, but no sensitive ear could possibly confuse the sounds. In the Essex scenes in ‘Great Expectations’ Dickens made use of the typical Essex word ‘fare,’ but he did not attempt to reproduce the dialect in essential respects. Mr. W. W. Jacobs’s delightful barge skippers are abstractions. They may be Essex men, but they are not recognizable as such. Enough that they amuse the bargee as much as they amuse everybody else; one of the authors of this book speaks from experience, having ‘tried’ some of Mr. Jacobs’s stories on an Essex barge skipper. No more about dialect must be written in the preface. Readers who are interested will find the rest of the authors’ information sequestered in a glossary.

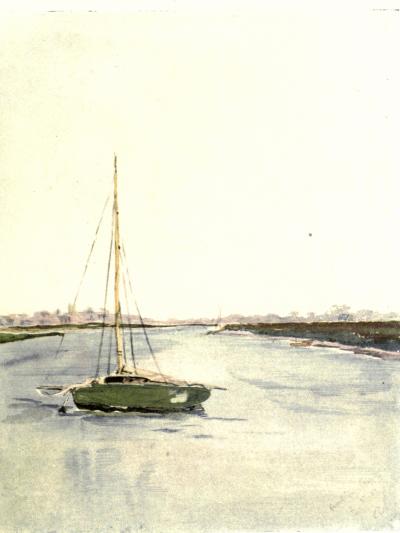

Mr. Arnold Bennett, who has settled in Essex near the coast, and is, moreover, a yachtsman, shares the enthusiasm of the authors for the peculiar character of the Essex estuaries. He makes his first appearance here as an illustrator. He has given his impressions of the scenery in which the barges ply their trade, and which is the setting of the following narrative.

It remains to say that in the narrative several names of places in Essex, as well as the real name of the barge, have been changed; and that the authors wish to thank the proprietors of the Evening News, who have allowed them to republish Sam Prawle’s salvage yarn, which was originally printed as a detached episode.

| I. COLOUR PLATES FROM WATER-COLOUR DRAWINGS BY ARNOLD BENNETT | |

| A Barge passing the Maplin Light | Frontispiece |

| The Swale River | to face page 24 |

| Bradwell Creek | 60 |

| Maldon | 84 |

| Beaumont Quay | 124 |

| Walton Creek | 136 |

| Landermere | 150 |

| The River Orwell | 164 |

| II. MONOCHROME PLATES FROM PHOTOGRAPHS | |

| A Barge at Sunset in the Lower Thames | 8 |

| In Sea Reach | 30 |

| Barges at an Essex Mill | 40 |

| Hauling a Barge to her Berth | 50 |

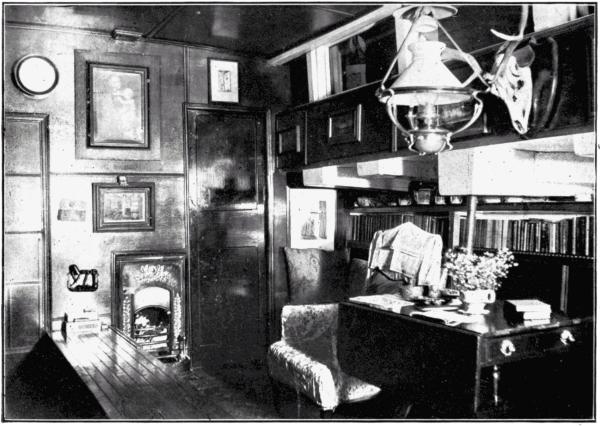

| The Dining Cabin | 72 |

| The Saloon | 92 |

| The Ark Royal | 102 |

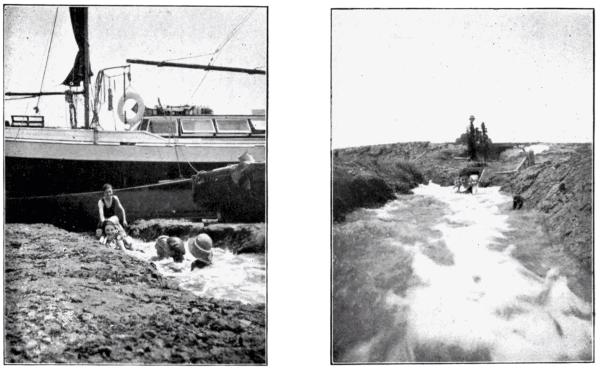

| Bathing in the Sluice at the Ark Royal’s Headquarters | 178 |

| Plan of the Ark Royal | 192 |

A FLOATING HOME

One winter I made up my mind that it was necessary to live in some sort of vessel afloat instead of in a house on the land. This decision was the result, at last pressed on me by circumstances, of vague dreams which had held my imagination for many years.

These dreams were not, I believe, peculiar to myself. The child, young or old, whose fancy is captive to water, builds for castles in Spain houseboats wherein he may spend his life floating in his element. His fancy at some time or other has played with the thought of possessing almost every type of craft for his home—a three-decker with a glorious gallery, a Thames houseboat all ready to step into, a disused schooner, a bluff-bowed old brig. He will moor her in some delectable water, and when his restlessness falls upon him he will have her removed to another place. Civilization shall never rule him.[Pg 2] As though to prove it he will live free of rates, and weigh his anchor and move on if the matter should ever happen to come under dispute. Nor will he pay rent resentfully to a grasping landlord. For a mere song he will pick up the old vessel that shall contain his happiness. Her walls will be stout enough to shelter him for a lifetime, though Lloyd’s agent may have condemned her, according to the exacting tests that take count of sailors’ lives, as unfit to sail the deep seas.

Certainly those who have the water-sense, yet are required by circumstances to earn their living as landsmen, have all dreamed these dreams. In many people the sight of water responds to some fundamental need of the mind. To the vision of these disciples of Thales everything that is agreeable somehow proceeds from water, and into water everything may somehow be resolved. When they are away from water they are vaguely uncomfortable, perhaps feeling that the road of freedom and escape is cut off. Inland they will walk, like Shelley, across a field to look at trickling water in a ditch, or will search out a dirty canal in the middle of an industrial town. The sea, which to some eyes seems to lead nowhere, seems to them to lead everywhere. Iceland and the Azores open their ports equally to the owner of any kind of vessel, and the wind is ready to blow him there, house and all. The water-sense is the contradiction in many people of the hill-sense. They[Pg 3] of the water-sense cannot tolerate that too large a slice of the sky, in which they love to read the weather-signs, should be eclipsed; the wonderful lighting of the mountains is less significant to them than the marshalling of vapours and tell-tale clouds upon their spacious horizon.

But this water-sense which lays a spell on you often exacts severe tolls of labour. The yachtsman who employs no paid hands, for instance, must sweat for his enjoyment; the simple acts of keeping a yacht in sea-going order, of getting the anchor and making sail, and of stowing sail and tidying up the ship when he has returned to moorings, mean exacting and continuous work. If he goes for a short sail the labour might reasonably be said to be disproportionate to the pleasure; and if he goes for a long sail the pleasure itself may easily turn into labour before the end. These disadvantages and uncertainties the yachtsman knows, and yet they are for him no deterrent. He may spend a miserable night giddily tossed about in an open and unsafe anchorage, and call himself a fool for being there; but the next week he will expose himself to the same discomfort. Why? Because it is in his blood; because he has this water-sense which compels him, bullies him, and enthrals him.

The houseboats of the Thames are famous centres of a dallying summer existence in which life tunes itself to the pace of the drifting punts and[Pg 4] skiffs, and seems to be expressed by the metallic melody of a gramophone or the tinkling of a mandolin. At night there is enough shelter for paper lanterns to burn steadily; and as the wind is tempered, so is everything else. All is arranged to add the practical touch of ease and comfort to the ideal of living roughly and simply, and the result is a mixture of paradox and paradise. One wonders what proportion of the population of the houseboats, if any, lives in the houseboats in the winter. The boats always seem to be empty then, and of course they were not designed for regular habitation. A wall or roof which, like

is not a meet covering for the winter. Nor would even a thoroughly weather-proof boat be so if it have no fireplace. But thought runs on from the spectacle of the mere Thames houseboat to the further possibilities of this mode of life. Why keep to the tame scenes of the upper Thames? Why not live on the Broads, under that clean vault of sky, scoured by the winds, among the wilder sights and sounds of nature? Thought runs on again. Why on the Broads, after all? They are a long way from London, and it may happen that one has to be often in London. And in the summer you might imagine that the upper Thames had been transported to Norfolk, so full are the Broads and[Pg 5] rivers of picnicking parties. Why, then, not live in a houseboat on sea water? Sea water is a great purifier. No fear that it will become stagnant or rank. Its transmuting process turns everything to purity. Take an odd proof. Even rubbish or paper in sea water is not an offence as it is in fresh water. Hurried along on the tide, it bears a relation to the great business of ships; but in fresh water it reminds one of disagreeable people, careless of all the amenities.

The houseboat, then, must be a ship lying with her sisters of the sea in a harbour. Attracted by the Government advertisements that appear from time to time in shipping newspapers, one thinks, perhaps, or buying an old man-of-war. But old men-of-war, though very roomy, are more expensive than you might suppose. Besides, in the conditions of sale there may be a stipulation that the buyer must break up the ship. A barque, such as is often bought by a Norwegian trader in timber, and spends her remaining days being pumped out by a windmill on deck, might serve for a houseboat. So would a steam yacht when the engines had been taken out. But then the draught of either is not light, and the occupier of a houseboat might want to lie far up a snug creek, and there even the highest spring tide would not give him the necessary depth. A sea houseboat might be built specially, but that is not the way of wisdom; the cost would be very great. The houseboat must be a[Pg 6] vessel of very easy draught, and also one that can be bought cheap and be easily adapted for the purpose.

Often had my thoughts carried me to this point by some such stages as have been described. But the floating home had remained a phantom because my desire for the sea was partly satisfied by the possession of a small yacht, the Playmate, of which I was the Skipper and my wife was the Mate, and in which we had spent all our holidays. Our home was a country cottage, which I had bought at Fleetwick, not far from a tidal river that strikes far into the heart of Essex. But at length circumstances, as I have said, caused the dream to become for me a very practical matter.

It happened in this way. The shadow of the change from governess to school had fallen on our two boys. We regretted it the more because there was no school within reach of home, and they were, in our opinion, too young to go to a boarding school. And so there seemed nothing to be done but to sell or let our cottage—if we could—where we had lived for nine years, and move to some place where there was a good school for the boys. Whatever place we chose had to be on or near salt water, for neither my wife nor I could seriously think of life without water and boats.

We found a satisfactory school near a tidal river in Suffolk, but we could not find a house—at least, not one we both liked and could afford. One day,[Pg 7] having returned dejectedly from a search as futile as usual, we were discussing the situation, which indeed looked hopeless, for our means were obviously unequal to what we wanted to do, when the idea of a floating home suddenly repossessed me with a fresh significance.

‘Let’s buy an old vessel,’ I said, ‘and fit her up as our house. We have often talked of doing it some day. That may have been a joke, perhaps. But why not do it seriously—now?’

The Mate evaded the startling proposal for the moment.

‘I wish the children wouldn’t grow up,’ she commented sadly.

‘If we don’t have the vessel,’ I persisted, ‘we shall fall between two stools, because with all the expenses—school, rent, and so on, which we’ve never had before—we shall have to give up the Playmate.’

‘That would be worse than anything.’

The mere idea of giving up our boat was more than we could contemplate—our boat in which we two had cruised alone together, summer and winter, on the East Coast, and from whose masthead more than once we had proudly flown the Red Ensign on our return from a cruise ‘foreign.’

‘I would rather live in a workman’s cottage and keep the boat, than live in a better house and have no boat,’ said the Mate emphatically.

‘Well, we’ve got to leave here, and it’s something to have found a decent school. I suppose, if we take a house really big enough to hold us, it will cost us forty pounds to move into it.’

‘Much more than that if you count all the new carpets, curtains, and dozens of other things we shall want.’

I thought an occasion for reiteration had arrived.

‘Just think. If we had a ship, we should do away with the expense of moving for one thing, the rent for another, and the rates and taxes for another. We may be absolutely sure our expenses will increase, and our income almost certainly won’t.’

The Mate was silent, so I continued: ‘Suppose we are reduced to doing our washing at home. Washing hung up to dry in the garden of a villa is one thing, but slung between the masts of a ship it is another. Not many people can scrub their own doorsteps without feeling embarrassed, but one can wash down one’s own decks proudly in front of the Squadron Castle.’

‘There is something in that.’ She was gazing out over the marshes, where the gulls and plover were circling. She sighed, and I knew she was thinking of the ‘move.’

I sat beside her and looked out of the window too, and the familiar sight of a barge’s topsail moving above the sea-wall caught my eye. ‘That’s what we should be doing,’ I said, pointing to the [Pg 9]barge—‘sailing along with our children and our household goods on board instead of waiting for pan-technicons to arrive with our furniture, and spending days in misery and discomfort moving it into a house we don’t like, and then paying a large rent every year for the privilege of staying in it. If we had a barge we could anchor clear of the town, and when the holidays came we could up anchor and clear off to a place more after our own hearts. Of course a barge is the very thing—the most easily handled ship for her size in the world. I see the way out quite clearly now.’

A Barge at Sunset in the Lower Thames

‘Yes, that sounds very jolly, but there would be a lot of drawbacks too.’ The Mate began to retreat towards the drawing-room.

‘Oh, but you haven’t heard half the advantages yet,’ I called after her.

The Mate wanted time. So did I. I lit a cigarette and thought for a few minutes over our position; and the more I thought the more sure I became that a barge would solve the problem for us. And when I joined her I felt that I had a pretty strong case.

‘Now listen to me,’ I said. ‘Not only should we save a great deal over the move, and over the rates and taxes, and have no landlord to interfere with us, but we should actually be freer than we are here. We should be sure of our sailing, which is one great advantage; and later, when the boys go to their public school, we can move wherever we like[Pg 10] and not be tied to a house for seven, fourteen, or twenty-one years. A move without a move—think of that. I am sure salt-water baths will be good for the children, and hot salt-water baths will be excellent for rheumatism—or anything of that sort. The barge will be warmer in the winter than a house, and cooler in the summer. She will be cheaper to keep up. You will save in servants and also in coals. You know you hate tramps, and hawkers, and barrel-organs. Well, you will be free from all these things. Of course, we don’t have earthquakes in England, but if we did have one we shouldn’t feel it. If we had a flood, it wouldn’t hurt us. You remember we paid about four pounds to have our burst water-pipes mended last winter, but we shouldn’t have that sort of thing in a barge. We shouldn’t be swindled over a gas-meter, and servants wouldn’t leave because of the stairs. It will be a delightful place for the children to bring their friends to, and no one will know whether we’re eccentric millionaires or paupers only just to windward of the workhouse. We’ll have the saloon panelled in oak, and white enamel under the decks, and our books and blue china all round. We’ll....’

I had just begun to warm to my work when an expression on the Mate’s face showed me that I had said enough and said it reasonably well. I had made an impression on her adventurous heart.

Two or three days after the conversation related in the last chapter the Mate and I fell into a vein of reminiscence and reconstructed a vision we had once shared of the ship that was some day to be our home. It had the proper condition of a vision that the thing longed for was unattainable; the vessel of our dreams had always been as far down on the horizon as the balance at the bank that would pay for her.

She was, above all things, to be beautiful, even for a ship, which is saying much—for who ever saw a sailing ship otherwise? Of course, she was to be square-rigged, for how else should we be able to[Pg 12] splice the mainbrace with rum and milk when the sun crossed the yard-arm? We fancied gorgeous pictures on her sails, so that the winds should be lovesick with them as with the sails of Cleopatra’s barge; an ensign aft, and streaming pennants of bright colours on her masts. Her poop, towering above the water, fretted and carved and blazoned with all the skill of bygone guilds, should have a gallery aft on which the captain and his wife would take their ease On either quarter, lit up at sundown, there would be tall poop lanterns covered with cunning tracery and magic, such as Merlin might have wrought, so that on windy nights the passing craft might see

Guns she would have on deck, and a fighting-top on the main, and a forecastle where the crew should man the capstan and weigh anchor to a chanty. Beneath her jibboom pointing heavenward she would set a spritsail heralding her on her way. We could see her with sails all bellied out in bold curves before a brave wind, and hear ‘the long-drawn thunder neath her leaping figure-head.’

Thus she would sail on her happy course, leaving behind ‘a scent of old-world roses.’ She would have to return, though, amid the smell of burnt crude oil or coal, for of course she could never go to[Pg 13] windward. And I am afraid we were going to have electric light too. After all, we are practical people.

I remember the evening of this reminiscence very well, because I suddenly became conscious that we were talking of the vision as a thing that had been supplanted by something else. There was no doubt about it. Our remarks had implied our consent to the scuttling of that glorious galleon. We took an artistic interest in the image, but it was no longer even good make-believe.

The more I had thought over it the more the idea of the barge had taken hold of me as a feasible scheme, for I was almost sure that the sale of the cottage and the Playmate would realize enough to buy the barge and pay for making her habitable.

I was familiar with the dimensions of a barge, and sketched out roughly to scale various plans by which we could have five sleeping cabins, a saloon, a dining cabin, kitchen, scullery, forecastle, and steerage. This occupation became so fascinating that I could hardly tear myself away from it at nights to go to bed.

As I am inclined to be the fool who rushes in while the Mate is the angel who fears to tread, it was natural for her to maintain certain objections for some time, even though thus early I could see that she was nearly as much bitten by the thought of the barge as I was. Here is the kind of discussion that would occur:

Skipper: You see, we’ve only got to be tidy and there’ll be heaps of room.

Mate: You don’t understand. Men never do. There are hundreds of things one doesn’t want in a yacht, even on a long cruise, which one must have in a house-boat.

Skipper: Well, there’ll be our cabin and a cabin for the boys, and another for Margaret, a spare cabin, the saloon, the dining-room, the bathroom, the kitchen, the forecastle, the steerage, and lots of lockers and cupboards everywhere.

Mate: Oh, you don’t understand.

Skipper: I could be bounded in a nutshell and feel myself the king of infinite space.

Mate: Hamlet won’t help us!

Skipper: But look at the alternative. If we go in for a house and can’t afford the rent we shall have to give up the Playmate and take to walks along a Marine Parade instead. Oh, Lord!

Mate: The children might fall overboard.

Skipper: We can have stanchions all round the ship and double lines.

Mate: What about slipping overboard between the ropes?

Skipper: Well, I don’t want to be laughed at, but if you really wish it we’ll have wire netting as well.

Mate: What about a water-supply? We can’t get on without plenty of fresh water.

Skipper: You shall have plenty.

Mate: How?

Skipper: In huge tanks.

Mate: What shall I do without my garden?

Skipper: That is the worst point and the only bad point. I’ve got no answer except that we must give up something, and the question is whether you would rather have the garden than everything else. Oh, happy thought!—some day we will tie up alongside a little patch and cultivate it.

Mate: Are you perfectly sure we shan’t have to pay rates?

At this point the Skipper could always cite in evidence the case of the ‘floating’ boathouse near by, which had been rated because it would not float. That proved to demonstration that anything capable of floating would not have been rated. Our friend Sam Prawle, an ex barge skipper, who lived in an old smack moored on the saltings, held himself an authority on rating in virtue of having taken part in this case. He had helped to build the floating boathouse, and therefore felt that his credit was involved in her ability to float.

Some years ago our saltings—the strip of marsh intersected by rills, which is covered by water only at spring tides—were not considered to have any rateable value. Later a good many yachts were laid up on them, and as the berths were paid for the saltings were rated. Then followed two or three[Pg 16] small wooden boathouses on piles, in which gear was kept, and on these a ferret-eyed busybody cast his eye. He reported them as being of rateable value. It was argued that the boats in which gear was stored, as distinguished from the yachts, might as well be rated too; but this would not hold water, for the simple reason that boats could be floated off and anchored in the river or taken away altogether, whereas the boathouses, though often surrounded by water, were buildings on the land.

To avoid paying rates, therefore, and at the same time to have a comfortable place in which to camp out and store things, the yacht-owner who employed Sam Prawle decided to build a floating boathouse. Sam and he, having fixed several casks in a frame, built a house on this platform.

Now it came to pass that the local ferret informed the overseers that this ‘building on the saltings’ did not float, and was therefore rateable. From that time onwards until the matter was decided our waterside world argued about little else but whether it was a house-boathouse or a boat-houseboat. The owner was invited to meet the overseers at the next spring tide to satisfy them on the point.

Sam worked hard all the morning of the trial, covering the casks with a thick mixture of hot pitch and tar. A small crowd gathered on the sea-wall to watch events. It was a good tide, and I, who was[Pg 17] present as chairman of the overseers, was glad, because it gave the owner a fair run for his money. My sympathy was all with him, although as an official I had not been able to give him the benefit of the doubt. As the tide rose near its highest point Sam and the owner, wading up to their thighs in sea-boots, did their utmost to lift the boathouse or move her sideways, but without success.

At the top of the tide, both of them, red in the face and sweating hard, managed to raise one end a couple of inches, and called on Heaven and the overseers to witness that the boathouse floated. As chairman of the overseers, I took the responsibility of saying that if they could shift her a foot sideways she should be deemed to have floated. They went at it like men, but the tide had fallen an inch before their first effort under these terms was ended, and two or three minutes later Sam was heard to say to the owner, ‘That ain’t a mite o’ use a shovin’ naow, sir. She’s soo’d a bit.’

And so the boat-houseboat turned out to be a house-boathouse after all, and was assessed at £1 a year. Sam used to pay the rate every half-year on behalf of his employer, not without giving the collector his views on the subject.

When the Mate had been convinced that we should really escape rates the thought of giving up her garden remained the last outwork of her very proper defences. But this position also fell in good[Pg 18] time. My foot-rule, my rough scale plans and piled-up figures of cubic capacity and surficial area carried all before them. I trembled for my arithmetic once or twice, however, when I proved that we should have very nearly as much room as in the cottage.

A barge, then, it was to be. Not a superannuated, narrow, low-sided canal barge; nor a swim-headed dumb barge or lighter, such as one can see any day of the week bumping and drifting her way up and down through London—the jellyfish of river traffic; nor yet, above all, an upper Thames houseboat of any sort, but a real sailing Thames topsail barge which could work from port to port under her own canvas, and meet her trading sisters in the open on their business.

The news that we were going to live in a barge spread like wildfire, and raised a storm of protest which took all our seamanship to weather. Many a time I had to clear off the land, so to speak, against an onshore gale with my barge and family. We thought our relations were unreasonable, for all barge skippers to whom we unfolded our plan became enthusiastic and said—tactful men!—that their wives were of the same mind. I claimed their views as expert at the time, though to be sure I knew well enough that there is a law of loyalty among sailormen whenever the old question of wives sailing with their husbands is discussed.

Our relations, who did not know a Thames topsail barge from a Fiji dug-out, regarded our scheme alternately as a sign of lunacy and as an injury to themselves. They were bent on shaking us; third parties were suborned to try tactfully to dissuade us, leading up to the subject through rheumatic uncles on both sides of the family. The emissaries lacked versatility, for they all approached the subject by way of uric acid, and the moment we heard the word rheumatism we took the weather berth by saying in great surprise, ‘You’ve come to talk about the barge, then?’

Having outsailed the emissaries, we were still bombarded with letters mentioning every possible objection. One said the barge would be dark, and we replied that we intended to have twenty-six windows. Another that it would be damp; against this we set our stoves. Another that it would be stuffy; and the windows were indicated once more. A fourth that it would be cold; and we brought forward the stoves again. A fifth declared that it would be draughty. To this last we intended to reply at some length that a ship with her outer and inner skin, and air-lock or space between the two, is the least draughty place possible. On second thoughts, however, we felt it would be waste of time, so, acting the part of a clearing-house, we switched the ‘draughty’ aunt on to the ‘stuffy’ uncle and left them to settle which it was to be.

Really we were too full of hope and plans to care what anyone said. Life was not long enough to get on with our work and answer objections too, so after a time we settled down in the face of the world to a policy of masterly silence.

In the meantime, as a first step, we took the measurements of a barge lying at Fleetwick Quay, so that we knew more accurately than before what room we should have, and could plan our home accordingly.

How those winter evenings flew! Armed with rulers, pencils, and drawing-boards, we sat in front of the drawing-room fire working like mad. We used reams of paper and blunted innumerable pencils making designs of the various cabins and placing the cupboards, the bunks, the bath, the kitchen range, the water-tanks, the china, the silver, the furniture, and the thousand and one things which make a house. After we had spent a week in deciding where the various pieces of furniture were to go, we discovered that they could not possibly be got in through the hatchways we had planned, and we accordingly designed a special furniture hatch. It was glorious fun, and we were always springing surprises on each other, and mislaying our pencils and snatching up the wrong one in the frenzy of a new idea. Indeed, we became so much absorbed that progress was hindered, for we could not be induced to look at each other’s plans[Pg 21] until we agreed to have two truces every night for purposes of comparison.

At any moment the house might be sold, and then we should want our barge, and buying a barge is not to be done in a moment or unadvisedly. The transaction is critical. We should not be able to go back upon it. Yacht copers, we knew, were as bad as horse copers, but both apparently were new-born babes compared with barge copers, if our information were correct.

The primitive explorers who came up the Thames in their rough craft examined the site of what was afterwards to be London, and saw that it was good. London is where it is because of the river. It is strange that Londoners should know so little, below bridges, of the river that made them. The reason, of course, is that the means of seeing it are very poor. How many Londoners could say how to come upon even a peep of the lower river within a distance of five miles of London Bridge? The common impression is that the river is impenetrably walled up by warehouses, wharfs, docks, and other forbidden ground. A simple way is to go by steamer when steamers are plying, but the best way is to be taken on board a sailing barge.

Taine said that the only proper approach to London was by the Thames, as in no other way could a stranger conceive the meaning of London. And from the water only is it possible to see properly one of the most beautiful architectural visions in the world—the magnificent front of[Pg 23] Greenwich Hospital, rising out of the water, as noble a palace as ever Venice imagined.

If this is the most splendid spectacle of the lower Thames, the most characteristic sight is that of the sailing barges, of which you may pass hundreds between London Bridge and the Nore. These are vessels of which Londoners ought to be very proud indeed; they ought to boast of them, and take foreigners to see them. But, alas! the very word ‘barge’ is a symbol of ungainliness and sordidness. What beauty of line these barges really have, from the head of the towering topsail to the tiny mizzen that lightens the work of steering! There is no detail that is weak or mean; a barge thriddling (as they say in Essex) among the shipping of the winding river in a stiff breeze is boldness perfectly embodied in a human design. The Thames sailing barges are one of the best schools of seamanship that remain to a world conquered by steam.

The Thames barge is worthy to be studied for three reasons: her history, her beauty, and her handiness. She is the largest sailing craft in the world handled by two men—often by a man and his wife, or a boy—and that in the busiest water in the world.

One hundred to one hundred and twenty tons is the size of an average barge nowadays. Seventy-five to eighty feet long by eighteen feet beam are her measurements. With leeboards up she draws about three feet when light and six when loaded; when[Pg 24] she is loaded, with her leeboards down, she draws fourteen feet.

For going through the bridges in London or at Rochester, or when navigating very narrow creeks, she will pick up a third hand known as a ‘huffler’ (which is no doubt the same word as ‘hoveller’)[1] to lend a hand.

[1] A hoveller is an unlicensed pilot or boatman, particularly on the Kentish coast. The word is said to be derived from the shelters or hovels in which the men lived, but such an easy derivation is to be mistrusted.

Some explanation must be given of how it is possible for two men to handle such a craft. In the first place, the largest sail of all, the mainsail, is set on a sprit, and is never hoisted or lowered, but remains permanently up. When the barge is not under way this sail is brailed or gathered up to the mast by ropes, much as the double curtain at a theatre is drawn and bunched up to each side. The topsail also remains aloft, and is attached to the topmast by masthoops, and has an inhaul and a downhaul, as well as sheet and halyard. Thus it can be controlled from the deck without becoming unmanageable in heavy weather. It is an especially large sail, and so far from being the mere auxiliary which a topsail is in yachts, it is one of the most important parts of the sail plan, and is the best-drawing sail in the vessel. It requires none of the coaxing and trimming which the yachtsman practises before he is satisfied with the set of the little sail which stands in so different a proportion and relation to his other sails. Often in a strong wind you may see a barge scudding under topsail and headsails only. The truth is that when a barge cannot carry her topsail it is not possible to handle her properly. The foresail, like the mainsail, works on a horse. These and several other things too technical to be mentioned here enable the barge to be worked short-handed.

THE SWALE RIVER

From Land’s End to Ymuiden the Thames barge strays, but her home is from the Foreland to Orfordness. Between these points, up every tidal creek of the Medway, Thames, Roach, Crouch, Blackwater, Colne, Hamford Water, Stour, Orwell, Deben, and Alde, wherever ‘there is water enough to wet your boots,’ as the barge skipper puts it, one will find a barge.

She is the genius of that maze of sands and mudbanks and curious tides

which is the Thames Estuary. Among the shoals, swatchways, and

channels, she can get about her business as no other craft can. The

sandbanks, the dread of other vessels, have no terror for her; rather,

she turns them to her use. In heavy weather, when loaded deep, she

finds good shelter behind them; when light, she anchors on their backs

for safety, and there, when the tide has left her, she sits as upright

as a church. Then, too, she is consummate in cheating the tides[Pg 25]

[Pg 26] and

making short cuts, or ‘a short spit of it,’ as bargees say. In this

the sands help her, for the tide is far slacker over the banks than in

the fairway, where her deep-draught sisters remain. While these are

waiting for water she scoots along out of the tide and makes a good

passage in a shoal sea.

What do all the barges carry? What do they not carry? were easier to answer. They generally start life—a life of at least fifty years if faithfully built and kept up—with freights of cement and grain, and such cargoes as would be spoilt in a leaky vessel. From grain and cement they descend by stages, carrying every conceivable cargo, until they reach the ultimate indignity of being entrusted only with what is not seriously damaged by bilge water.

Barges even carry big unwieldy engineering gear, and when the hatches are not large enough, the long pieces, such as fifty-foot turnable girders, are placed on deck. The sluices and lock-gates for the great Nile dam at Assuan were sent gradually by barge from Ipswich to London for transhipment.

Hay and straw—for carrying which more barges are used than for any other cargo except cement—must be mentioned separately. After the holds are full the trusses of hay or straw are piled up on deck lo a height of twelve to fifteen feet. At a distance the vessel looks like a haystack adrift on the sea. The deck cargo, secured by special gear, often weighs as much as forty tons, and stretches[Pg 27] almost from one end of the ship to the other. There is no way from bow to stern except over the stack by ladders; the mainsail and foresail have to be reefed up, and a jib is set on a bowsprit; and the mate at the wheel, unable to see ahead, has to steer from the orders of the skipper, who ‘courses’ the vessel from the top of the stack. To see a ‘stackie’ blindly but accurately turning up a crowded reach of London River makes one respect the race of bargees for ever. How a ‘stackie’ works to windward as she does, with the enormous windage presented by the stack, and with only the reduced canvas above it, is a mystery, and is admitted to be a mystery by the bargemen themselves. One of them, when asked for an explanation, made the mystery more profound by these ingenuous words: ‘Well, sir, I reckon the eddy draught off the mainsail gits under the lee of the stack and shoves she up to wind’ard.’

The Thames barge is a direct descendant of the flat-bottomed Dutch craft, and her prototype is seen in the pictures of the Dutch marine school of the seventeenth century. Both her sprit and her leeboards are Dutch; the vangs controlling the sprit are the vangs of the sixteenth-century Dutch ships; and until 1830 she had still the Dutch overhanging bow, as may be seen in the drawings of E. W. Cooke. The development of her—the practical nautical knowledge applied to her rigging and gear[Pg 28]—is British, like the invincible nautical aplomb of her crew.

Those who have watched the annual race of the Thames barges in a strong breeze have seen the perfection of motion and colour in the smaller vessels of commerce. The writer, when first he saw this race and beheld a brand-new barge heeling over in a wind which was as much as she could stand, glistening blackly from stem to stern except where the line of vivid green ran round her bulwark (a touch of genius, that green), with her red-brown sails as smooth and taut as a new dogskin glove, and her crew in red woollen caps in honour of the occasion, exclaimed that this was not a barge, but a yacht.

A barge never is, or could be, anything but graceful. The sheer of her hull, her spars and rigging, the many shades of red in her great tanned sails, the splendid curves of them when, full of wind, they belly out as she bowls along, entrance the eye. Whatever changes come, we shall have a record of the Thames barge of to-day in the accurate pictures of Mr. W. L. Wyllie. He has caught her drifting in a calm, the reflection of her ruddy sails rippling from her; snugged down to a gale, her sails taut and full, and wet and shining with spray; running before the wind; thrashing to windward with topsail rucked to meet a squall; at anchor; berthed. Loaded deep or sailing light; with towering[Pg 29] stacks of hay; creeping up a gut; sailing on blue seas beneath blue skies; or shaving the countless craft as she tacks through the haze and smoke of a London reach, she is always beautiful.

Of course the bargees pay their toll of lives like other sailors. They are not always in the quiet waters of liquid reflections that seem to make their vessels meet subjects for a Vandevelde picture. Many stories of wreck, suffering, and endurance might be told, but one will suffice—a true narrative of events. The barge The Sisters, laden with barley screenings, left Felixstowe dock for the Medway one Friday morning. She called at Burnham-on-Crouch, and on the following Friday afternoon was between the Maplin Sands and the Mouse Lightship, when a south-west gale arose with extraordinary suddenness. Before sail could be shortened the topsail and jib were blown away. The foresail sheet broke, and the sail slatted itself into several pieces before a remnant could be secured. Under the mainsail and the remaining portion of the foresail the skipper and his mate steered for Whitstable. Then the steering-chain broke, and nothing could be done but let go the anchor. They were then in the four-fathom channel, about three-quarters of a mile inside the West Oaze Buoy.

The seas swept the barge from end to end. Darkness fell, and for an hour the skipper burnt flares, while his mate stood by the boat ready to[Pg 30] cast it off from the cleat in an emergency. The emergency came before there was a sign of approaching rescue. The barge suddenly plunged head first and disappeared. The mate, with the instinct of experience, cast off the painter of the boat as the deck went down beneath his feet. Both men went under water, but the boat was jerked forwards from her position astern as the painter released itself, and the men came up to find the dinghy between them. It was a miracle, but so it happened. They grabbed hold of her before she could be swept away, climbed in, and began to bail out the water. With one oar over the leeside and the other in the sculling-hole they made for the Mouse Lightship. ‘If we miss that,’ said the skipper, ‘God knows where we shall go!’ For four hours they struggled towards the Mouse light, although they could not always see it, and eventually came within hailing distance. They shouted again and again, but the crew of the lightship, though they heard them, could not at first see them. At last the boat came near enough for a line to be thrown across it. The boat was hauled alongside and the men were drawn up into safety, ‘eaten up with cramp,’ as the skipper said, and numb with exhaustion and exposure. At the same moment the boat, which was half-full of water, broke away and disappeared.

Perhaps the best time to see a barge is while [Pg 31]deep laden, she beats to windward up Sea Reach, on a day when large clouds career across the sky, sweeping the water with shadows, as the squalls boom down the reach, and the wind, fighting the tide, kicks up a fierce short sea. Then, as the fishermen say, the tideway is ‘all of a paffle.’ As the barge comes towards you, heeling slightly (for barges never heel far), you can see her bluff bows crashing through the seas and flinging the spray far up the streaming foresail. It bursts with the rattle of shot on the canvas. You can see the anchor on the dripping bows dip and appear as sea after sea thuds over it, and the lee rigging dragging through the smother of foam that races along the decks and cascades off aft to join the frothy tumult astern. You can see the weather rigging as taut as fiddle-strings against the sky. Now she is coming about! The wheel spins round as the skipper puts the helm down, and the vessel shoots into the wind. She straightens up as a sprinter relaxes after an effort. The sails slat furiously; the air is filled with a sound as of the cracking of great whips; the sprit, swayed by the flacking sails, swings giddily from side to side; the mainsheet blocks rage on the horse. Then the foresail fills, the head of the barge pays off, and as the mate lets go the bowline the stay-sail slams to leeward with the report of a gun. The mainsail and topsail give a last shake, then fill with wind and fall asleep as the vessel steadies on her[Pg 32] course and points for the Kentish shore. As she heels to port she lifts her gleaming side and trails her free leeboard as a bird might stretch a tired wing. She means to fetch the Chapman light next tack.

In Sea Reach

A fleet of barges shaking out their sails at the turn of the tide and moving off in unison like a flock of sea-birds is a picture that never leaves the mind. And darkness does not stop the bargeman even in the most crowded reaches so long as the tide serves. Every yachtsman accustomed to sail in the mouth of the Thames has in memory the spectral passing of a barge at night. She grows gradually out of the blackness. There is the gleam of her side light, the trickling sound of the wave under her forefoot, the towering mass of sombre canvas against the sky, the faint gleam of the binnacle lamp on the dark figure by the wheel, the little mizzen sail right aft blotting out for a moment the lights on the far shore, and the splash-splash of the dinghy towing astern. There she goes, and if the fair wind holds she will be in London by daybreak.

When the barge Osprey berthed at Fleetwick Quay to unload stones for our roads we went on board, and took our old friend Elijah Wadely, the skipper, into our confidence.

’Ef yaou’re a goin’ to buy a little ould barge, sir,’ said Elijah, ‘what yaou wants to know is ’er constitootion. My meanin’ is, ef yaou knaow who built she, yaou’ll know ef she was well built; and ef yaou knaow what trade she’s bin’ in you can learn from that. Naow ef she’s a carryin’ wheat, or any o’ them grains, what must be kept dry, yaou’ll knaow she can’t be makin’ any water, or do, she ’ouldn’t be a carryin’ ’em. Then agin, water don’t improve cement, and that’s a cargo what’s wonnerful heavy on a barge is cement, and ef bags is spoilt that’s a loss to the skipper, that is. So you can take it that barges what carry same as grain and oilcake and cement and bricks and such-like is mostly good too.

‘And when yaou knaows what she’s bin a carryin’ yaou wants to know where she’s bin a carryin’ it to; for some berths is good and some is[Pg 34] wonnerful bad, specially draw-docks,[2] and what sort of condition she’s in is all accordin’ to where she’s bin a settin’ abaout. I’ve knaowed many a barge strain herself settin’ in a bad berth, whereas a barge of good constitootion settin’ in the same berth will maybe wring a bit and make water for a trip or two, but she’ll take up agin. Yes, sir, ef yaou’re a goin’ to buy a little ould barge—and there ain’t a craft afloat as ’ud make a better ’ome, as my missis ’as said scores o’ times—yaou must study ’er constitootion.’

[2] Berths on the river bed, where carts come alongside at low water to unload the barges.

‘How’s trade, Lijah?’

‘Well, sir, I’ve bin bargin’ forty years, and I don’t fare to remember when times was so bad in bargin’ afore.’

‘What do you think we could get a decent 120-ton barge for, Lijah, supposing we wanted a big one?’

‘I doubt yaou ’ont get ’un under five or six hundred paounds. Yaou see, sir, what bit o’ trade there is them bigger barges same as 120 tons and up’ards gits, for they on’y carries two ’ands same as we, what can on’y carry 95 ton, though by rights they ought to carry a third ’and.’

‘Do you think we could get a sound 90 tonner for two hundred pounds, because that’s the size we’ve practically decided on?’

‘I don’t want to think nawthen about that, I knaow yaou can. Why, on’y last week the Ada was sould for one ’undred and sixty pound, as good a little ould thing as any man ever wanted under ’im. But yaou wants to be wonnerful careful-like in buyin’ a barge. Yaou know that, sir, as well as I do, and my meanin’ is there’s barges and barges. As I was a tellin’ yer, yaou wants to know her constitootion first, and then yaou wants to knaow her character. Yaou don’t want to take up with a craft what yaou can’t press a bit, or what’ll bury ’er jowl or keep all on a gnawin’ to wind’ard or ’ont lay at anchor easy or is unlucky in gettin’ run into.’

‘Why, you’re not superstitious, are you, Lijah?’

‘No, no, sir. I’m on’y tellin’ yer there’s barges and barges. Look at this little ould Osprey, sir. Yaou can see she’s got a new bowsprit. Well an’ that’s the third time she’s bin in trouble since yaou’ve knaowed she, ain’t it? We’d just come off the loadin’ pier at Southend to make room for another barge, and we layed on that ould moorin’ under the pier right agin the foot of the beach ready for the mornin’s high water. Well, she took the graound all right, for she d’ent on’y float there about faour hours out of the twelve, and I went belaow to turn in for a bit. She ’adn’t barely flet when I felt her snub, and there was a barge atop ’o she and aour bowsprit gone. I knaow wessels has laid on that[Pg 36] ould moorin’ for the last twenty year, and never ain’t heard tell of one bein’ in trouble afore.

‘Soon as we’d got t’other barge clear, I went up and tould the guvnor. “Lijah,” ’e says, “ef I was to put that little ould Osprey in my back-yard she’d get run into.” Yes, that’s the truth, that is; you can’t leave that ould barge anywhere, no matter where that is, but the ould thing’ll have suthen atop o’ she. And what’s more, the guvnor’s lost every case he’s took up on ’er so far, though he was allus in the right.

‘Naow the Alma, what my wife’s cousin Bill Stebbins is skipper of, is all the other way raound. That ould thing’s bin run into twice since Bill’s had ’er, once on her transom and once on her port side just abaft the leeboards, and there warn’t no law case nor nawthen, but each time the party what done it agreed on a sum and paid it, and the ould thing made money over it for ’er guvnor.

‘I once see’d the Alma do a thing what I wouldn’t ’ave believed not if forty thaousand people told me. She was a layin’ in Limehouse reach, stackloaded and risin’ to abaout twenty fathom o’ chain. There was a strong wind daown, and she was a sheered in towards the shore. Bill’s mate was a goin’ ashore for beer, and I ’eard Bill tellin’ ’im to ’urry up. I knaowed why he tould the mate to be quick, because that blessed ould ebb was running wonnerful ’ard, and sometimes that’ll frickle abaout[Pg 37] and make a barge take a sheer aout, and p’raps break her chain, which barges do sometimes in the London River. Well, suddenly I seed that little ould Alma sheer right off into the river and snub up with a master great jerk what pulled her ould head raound agin. Then I see’d ’er with her chain up and daown a drivin’ straight for the laower pier, where I reckoned she’d be stove in or suthen, and there was Bill alone on board as ’elpless as a new-born babe, as the sayin’ is, for a’ course ’e couldn’t lay aout no kedge nor nawthen by ’isself.

‘Well, as true as I’m a settin’ ’ere that lucky ould thing come a drivin’ athwart till she fetches into the eddy tide below the upper pier, and then she goes away to wind’ard, although there was a strong wind daown, mind yer, till she fetches up alongside another barge, the Mabel, what was a layin’ there, and all Bill ’ad to do was to pass the Alma’s stay fall raound the Mabel’s baow cleat and back agin. Yes, sir, that was the head masterpiece that ever I did see.’

A few days afterwards we happened to see the Norah Emily down in the mouth of our river. This was the barge commanded by Bill Stebbins, the former skipper of the Alma. We took a rather mischievous pleasure in going on board to find out whether Bill Stebbins would confirm all Elijah had told us. We fancied that Elijah would have spoken more circumspectly about the unfailing luck of the[Pg 38] Alma, if he had guessed that Bill was likely to come round our way. But our doubts soon became remorse. Elijah was vindicated.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Bill, ‘that ould Alma was the luckiest ould basket ever built; that d’ent matter where yaou left she, she d’ent never git into trouble. There was faour on us once’t a layin’ in the middle crick below the Haven, the Lucy, the Susan, the Fanny, and my little ould Alma. We had to wait our turn at the quay for loadin’ straw, so the mate and me went off home for a day or two. Well, that come on to blaow suthen hard, that did, and all they there barges was in some kind of trouble, but the Alma she just stayed where she were and d’ent come to no manner o’ harm.

‘Then agin, same as in the London docks, yaou ast any barge skipper yaou like haow long a barge can lay there without a lighter or a tug or suthen wantin’ she to shift. None the more for that, I’ve bin, there plenties o’ times with that little ould Alma, and she warn’t niver in no one’s way. I remember off Pickford’s wharf, Charing Cross, we ’ad to shift to make room for another barge. I ’ad to goo off to fix up another freight, but reckoned to be back by six o’clock, so I tould the mate to git a hand to help shift she and make fast in case I warn’t back tide-time. Well, arter I got my freight I meets one or two friends, and what with one thing and another, I den’t git back till eleven o’clock o’ night.[Pg 39] I couldn’t find that mate, or, do, I’d a given he suthen, for there was that blessed ould thing made fast with a doddy bit o’ line no bigger’n yaour finger, whereas by rights she ought to have had three or faour of aour biggest ropes to hold she from slippin’ daown the wind. Anyway, there she lay end on just right for slippin’ off, and niver even offered to move. As yaou knaow, sir, scores and scores o’ barges ’av bruk the biggest rope they carry that way and gone slidin’ daown the wind. The Mary Jane did, just above Bricklesey[3] on the way to Toozy,[4] and buried her ould jowl that deep in the mud on t’other side of the gut that I was skeered she wasn’t goin’ to fleet.

[3] Brightlingsea.

[4] St. Osyth.

‘But there y’are, that Mary Jane ’ouldn’t never set anywhere where any other barge would; and ef her rope was strong enough she’d have tore the main cross chock or anything else aout o’ she. That’s the masterousest thing, that is, but I s’pose that’s all accordin’ to the way her bottom is. But that ould Alma—well, I’ve heard plenties o’ times afore I took she what a lucky bit o’ wood she were. Look at here, sir. We was up Oil Mill Crick by Thames Haven there and the wind straight in, and us had a bit o’ bad luck comin’ aout, for us stuck on that slopin’ shelf o’ mud right agin the salts there. I felt wonnerful anxious, for there warn’t three foot to spare, and ef she’d a slipped off she’d a bruk [Pg 40]’erself to pieces. I don’t reckon any other barge ’ud have hild on there, but that ould Alma did. She just set up there same as a cat might on a table.

‘In Shelly Bay, too, just above the Chapman Light, she done a thing what no other barge ’ould have done. Us couldn’t let goo our anchor where us wanted to, as there was another barge, the Louisa, agin the quay. I had to goo off to see the guvnor, so I ast the skipper o’ the Louisa to give my mate a hand when the Louisa come off, for a course the Alma hadn’t got near enough chain aout. Well, that bein’ a calm then my mate tould the skipper o’ the Louisa not to trouble, as he warn’t goin’ to shift till the mornin’. That bein’ a calm then warn’t to say that ’ud be a calm in the mornin’; and it warn’t, for that come on to blaow a strorng hard wind straight on shore.

‘That ould thing begun to drag her anchor, but as soon as ever her ould starn tailed on to that beach her anchor hild, and she lay head on to the sea as comfortable as yaou could want to be. There ain’t a mite o’ doubt but what ninety-nine barges out ’er a hundred ’ud have paid off one way or t’other, and come ashore broadside on and done some damage, for there’s a nasty swell comes in there.’

Barges came and went in our river. We inspected some at the quay, and sailed down in the Playmate to talk to the skippers of others. We soon learned enough about barges to fill a book. We heard how the day the Invicta was launched she ran into another vessel and her skipper’s hand was badly cut; how his wife tried (in the Essex phrase) to ‘stench’ the bleeding; how the skipper swore that the ship would be unlucky, as blood had fallen on her on the day she was launched; and how the wife herself died on board on the third trip. We heard of good barges and bad, of lucky barges and unlucky; of barges that would always foul their anchors, and others that never did; of barges that would carry away spars or lose men overboard, or break away from their berths, and of others that were as gentle as doves.

Barges at an Essex Mill

It seemed that barges are much like human beings; when young, they can stand strains and do heavy work which they have to give up when middle-aged. If they have a weakness of constitution it reveals itself when they are young; but having passed the critical age, they settle down to a long useful life, and it is not uncommon for them to be still at work after fifty or sixty years. But the most important result of our researches was the universal opinion that a sound 90 tonner was to be got at our price.

At least, that was the most important fact from my point of view; but

I ought in truthfulness to say that while I had been making notes

likely to[Pg 41]

[Pg 42] help me to buy a good barge with a sound constitution, the

Mate had looked upon our accumulated information from a different

angle, and had been giving her attention to barges’ characters.

I might have foreseen this, for she always looked on the Playmate as a living thing. She has the feeling of the bargemen, who say of an old vessel, ’Is she still alive?’ I was not prepared, however, for her to tell me that, however sound a barge might be, I was not to buy her unless her character was good. I argued in vain.

‘Do you think I would be left with the children on board a barge like the Osprey, always being run into? Or like the Mildred, always dragging her anchor? Or the Charlotte, who has thrown two men overboard? Not I!’

I pointed out that she had so successfully acquired the spirit of barging that she was evidently made for the life. The suggestion was received with favour. We were indeed now so deep in the business that we were beyond recall. Nothing remained but to choose our particular 90 tonner with a good character.

‘Ships are but boards, sailors but men; there be land-rats and water-rats, land-thieves and water-thieves.’

The next thing that happened was that we received an offer of £375 for our cottage. After an attempt to ‘raise the buyer one’—an attempt that would have been more persistent had our desire to become barge-owners been less ardent—we accepted the offer. We ought to have got more, but as the barge market was flat we salved our consciences on the principle that what you lose on the swings you gain on the roundabouts.

We entered the barge market as buyers. It is impossible to ‘recapture the first fine careless rapture’ of those days. In every 90-ton barge we looked on we saw the possible outer walls of our future home. The arrival of the post had a new significance, for we had made known far and wide the fact that we were serious buyers. We turned over our letters on the breakfast-table every morning like merchants who should say, ‘What news from the Rialto?’

The first barges we heard of were, according to the advertisement, the ‘three sound and well-found sailing barges, the Susan, the Ethel, and the Providence, of 44 tons net register.’ Each of these was about 90 tons gross register, and at that moment of optimism the chances seemed at least three to one that one of them would suit us.

Let it be said here that the net registered tonnage of barges is a conventional symbol. Whether a barge carries 100 or 120 tons, the net tonnage is always 44 and so many hundredths—often over ninety hundredths. If by any miscalculation in building she works out at 45 tons or more, a sail-locker or some other locker is enlarged to reduce her tonnage, for vessels of 45 tons net register and upwards have to pay port dues in London.

It is, of course, the ambition of every owner, whether of a 5-ton yacht or the Leviathan, to get his net registered tonnage as low as possible, so as to minimize his port and light dues. One well-known yachtsman who was having his yacht registered kindly assisted the surveyor by holding one end of the measuring tape. In dark corners the yachtsman could hold the tape as he pleased, but in more open places the surveyor’s eye was upon him. The result was curious; the yacht turned out to have more beam right aft than amidships. ‘She’s a varra funny shaped boat,’ said the surveyor doubtfully. Luckily his dinner was waiting for him, and[Pg 45] he did not care to remeasure a yacht about the precise tonnage of which no one would ever trouble himself.

We hurried off to consult Elijah Wadely about the Susan, the Ethel, and the Providence.

‘Not a one o’ they ’on’t suit yaou, sir,’ said Lijah. ‘That little ould Susan was most tore out years ago—donkeys years ago. And that ould Ethel—- well, she’s only got one fault.’

‘What’s that?’

‘She were built too soon,’ chuckled Lijah. ‘And that ould Providence is abaout the slowest bit o’ wood ever put on the water. No, no, sir; none o’ they ’on’t do.’

We were disappointed, of course, but not long afterwards we heard of another barge laid up near a neighbouring town, and went to see her. She had been tarred recently and looked fairly well, but we did not trust the owner. Not long before he had tried to sell us an old punt (also freshly done up) for twenty-five shillings—a punt which we discovered had been given to him for a pint of beer. We looked over the barge accompanied by the owner, who rather elaborately pointed out defects, which he knew, and we knew, were unimportant, in a breezy and open manner, as one trying to impress us with his candour.

When the Mate was out of hearing he used endearing and obscene language about the barge, as[Pg 46] one who should say, ‘Now you know the worst of her and of me.’ However, the memory of the punt, and what Falstaff describes in Prince Hal’s eyes as ‘a certain hang-dog look,’ convinced us that the barge would never stand a survey, and we learned afterwards that she was as rotten as a pear below the water-line.

We had hardly returned from this inspection when we heard of three more barges to be sold. They were engaged in carrying cement to London and bringing back anything they could get, and at that moment were lying off Southwark.

We went at once to London. The next day we visited the Elizabeth, one of the barges, and were invited into the cabin by the skipper and his wife—not any of our Essex folk, worse luck. I began to make use of some of the knowledge I had acquired. In this I was checked by the lady of the barge, who said, ‘It seems to me, mister, yer wants to know something, and if yer wants us to speak yer ought to pay yer footing.’

I sent for a bottle of gin, already painfully recognizing that looking at barges in our country was one thing, and in London another. The skipper and his wife appeared to be thirsty souls, for soundings in the bottle fell rapidly. We discussed the weather and things generally while I took stock of these people, who were to me a new and disagreeable type. I wondered whether they would be more likely[Pg 47] to speak the truth before they finished the gin—which they seemed likely to do—or afterwards. Meanwhile I looked round me.

The Elizabeth had a small cabin and no ventilation worth mentioning, and as the atmosphere grew thicker, in self-defence I lit my pipe. Then I tried again.

‘Well, yer see, mister, it’s this ’ere way. You wants to buy the barge, and if I says she’s all right you buys ’er, and I lose my job; and if I says she ain’t all right I gits into trouble with my guvnor.’

‘Quite so,’ I said, ‘but the survey will show whether she is sound or not, and I want to save the expense of having a survey at all if she isn’t sound. If I do have her surveyed and she is sound your owner will sell her anyhow. So you may just as well tell me.’

‘D’yer mind saying all that over again?’ remarked the skipper.

I did so, and the pair helped themselves to gin once more. ‘What I says is this,’ said the lady, ‘this is very fine gin and a very fine barge.’

‘Yus, the gin’s all right, and so’s the barge,’ said the skipper, adopting the brilliant formula. ‘I can’t say fairer’n that, can I?’

The situation was becoming hopeless and my anger was rising, so I said curtly, dropping diplomacy, ‘What I want to know is, does she leak, is she sound, what has she been carrying, where has she been trading to?’

“Can’t say, mister. This’s our first trip in ’er,” said the skipper.

“Fine gin and fine barge,” repeated the woman.

We fled.

The second barge we visited was a good-looking craft, built for some special work, but she lacked the depth in her hold which we required for our furniture.

The third barge, the Will Arding, lay off deep-loaded in the fairway waiting for the tide to berth. The skipper was not on board, but a longshoreman in search of a drink gave me a list of public-houses where he might be found.

At the first three public-houses knots of grimy mariners had either just seen George or were expecting him every minute, and if I would wait one of them would find him. At the fourth public-house the same offer was made, and in despair I accepted it.

It required more moral courage than I possessed to wait with thirsty sailors, their mugs ostentatiously empty, without ordering drinks all round; yet, as I expected, the huntsman returned in a few minutes puffing and blowing—which physical distress was instantaneously cured by sixpence—to say that George was nowhere to be found.

With a gambler’s throw, I tried one public-house not on my list, and George was not there; but as[Pg 49] usual there were those who knew where to find him if the gentleman would wait.

I never met George, and, judging by his friends, I did not want to; though, to be just, he might have been blamelessly at home all this time with his family. And there, as a matter of fact, he very likely was, for I learned later, what everyone else knew and I might have suspected, that he had been paid off, as this was the Will Arding’s last trip before being sold.

We wandered back to the waterside and stood gazing at the slimy foreshore, the barges and lighters driving up on the muddy tide, the tugs fussing up and down, their bow-waves making the only specks of white in the gloomy scene, the bleak sooty warehouses, and the wharfs with their cranes like long black arms waving against the sky. We were declining rapidly into depression, when I saw emerging from the shadow of the bridge a stackie in charge of a tug.

How clean and dainty she looked, like a fresh country maid marketing in a slum! Her fragrant stack of hay brought to us a whiff of the country whence she had come, and a vision of great stretches of marshland dotted with cattle, and hayricks sheltered behind sea-walls waiting for red-sailed barges to take them away.

The tug slackened speed; the stack-barge was being dropped. She seemed familiar, and as she came[Pg 50] nearer I saw her name, the Annie. Joe Applegate, the skipper, a trusted friend of ours, was at the wheel. How pleased I was now that I had spent those fruitless half-hours looking for George!

“Ain’t that a fair masterpiece a seein’ yaou here, sir!” shouted Joe in good Essex that raised our spirits like a bar of cheerful music. “And haow’s them little ould booeys?”

He had come with 70 tons of hay for the London County Council horses. We were doubly glad to look on his honest face when he came on shore and told us that he knew the Will Arding well and had traded to this wharf for years.

“Yes, yes, sir; knaowed her these twenty years. She belongs to a friend of my guvnor’s, and were built by ’is father at Sittingbourne, and ’as allus been well kep’ up by ’is son. She’d be gettin’ on for forty, I reckon, and a course she ain’t same as a new barge, but she’ll last your lifetime if you’re on’y goin’ to live in she and goo a pugglin’ abaout on her same as summer-time and that. She’ll ’ave a cargo of cement aboard naow—90 to 95 tons she mostly carry, and I ain’t never heard of ’er spoiling a bag yet. She’s got a good constitution, she ’as, but none the more for that yaou can watch she unloaded to-morrer if yaou’ve a mind to, and ef she suits yaour purpose ave ’er surveyed arterwards.”

The Mate asked about her character.

“She ain’t never bin in trouble but once, that I [Pg 51]knaows on, and then she were run into by a ketch and got three timbers bruk on ’er port bow. No, no, sir; there ain’t nawthen agin that little ould thing.”

Hauling a Barge to her Berth

We seemed to be on the right tack at last. Having learned what more we could, we prepared to come to grips with the owner.

The owner of the Will Arding, whom we met the next day, was a kindly simple man who told us all we needed to know about the vessel. We had prepared ourselves to cope with a coper of the worst kind; but we were soon disarmed, and that not to our detriment. He told us that the barge had just finished her contract, and as, in his opinion, the days of small barges were over, except in good times, he was going to sell her, as she was barely paying her way. He showed us the record of her trips, the cargoes she had carried, the places she had traded to, and the repairs done to her from time to time.