Project Gutenberg's The Story of Geronimo, by James Arthur Kjelgaard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Story of Geronimo Author: James Arthur Kjelgaard Illustrator: Charles Banks Wilson Release Date: December 15, 2012 [EBook #41630] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF GERONIMO *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan, Ross Cooling and the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

PUBLISHERS Grosset & Dunlap NEW YORK

SIGNATURE BOOKS GERONIMO

Š JIM KJELGAARD 1958

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9837 The Story of Geronimo

For

Eleanor Gefroh

who has been the dearest of friends to me and mine

| I | Duel by Stallion | 3 |

| II | Raiding the Papagoes | 13 |

| III | Alope | 28 |

| IV | Massacre | 39 |

| V | Flight | 51 |

| VI | Revenge | 59 |

| VII | The White Men | 71 |

| VIII | The Battle of Apache Pass | 80 |

| IX | A Wounded Chief | 90 |

| X | A Chief Dies | 99 |

| XI | Geronimo in Chains | 108 |

| XII | Flight into Mexico | 116 |

| XIII | Fortress Paradise | 127 |

| XIV | Chief Gray Wolf | 136 |

| XV | The Discontented | 145 |

| XVI | Hunted Like Wolves | 153 |

| XVII | A Gallant Soldier | 163 |

| XVIII | The Last Surrender | 170 |

Geronimo crawled up the hill so carefully that no stalk of grass moved, and no bush quivered. A pair of crested quail, feeding on insects in the grass, merely glanced up when he passed and went on feeding. Geronimo reached the top of the hill and crouched down in the grass.

Beyond were more hills, the near ones low, rocky, and given more to shrubs and grass than to trees. Geronimo's eyes strayed across the Arizona landscape to the east. There lay No-doyohn Canyon, where Geronimo had been born in 1829, just twelve years earlier. There his father had died when Geronimo was five years old. In the far distance beyond the canyon, tall, pine-clad mountains rose.

Geronimo looked down the slope on a wickiup. This Apache house was built of poles thrust into the ground, with deer skin walls and a smoke hole in the center of the roof. It was the home of Delgadito, a mighty chief among the Mimbreno Apaches, the tribe to which Geronimo belonged. Delgadito was so mighty that only the great chief, Mangus Coloradus himself, outranked him.

Delgadito owned many horses. Most of them grazed by day in pastures far from the village. But his black war stallion, his nimble-footed gray hunting horse, and the mare that his wife rode were only absent from their picket ropes when a rider was using them.

Now the gray hunting horse was gone, which meant that Delgadito was out after deer. But the mare and the stallion were still there. Geronimo had come to steal the war horse. This, however, was not the time to do it.

The mare's presence proved that Delgadito's wife was home. If she saw Geronimo stealing the war horse she would tell her husband. The punishment sure to follow would be harsh and long remembered. Delgadito knew how to use a switch on headstrong boys. Geronimo crouched in his hiding place, waiting.

Soon Delgadito's wife came from the wickiup, mounted her mare, and rode away. Geronimo rose and walked swiftly down the hill.

The stallion raised its head and watched with eyes that were fearless and questioning. Geronimo grasped the buckskin tie rope, and was drawing the horse to him when—

"You leave my uncle's war horse alone!"

A girl had come from the wickiup. Geronimo was so interested in the horse that he did not even know she was near until she spoke. Her name was Alope, and she was Delgadito's niece. Geronimo thought she was so lovely that the most dazzling maidens of the Mimbreno or any other tribe were drab beside her. When grown, such a girl would be too good for any warrior. Only a chief would be worthy to have her as his wife.

Geronimo said, "I must have this stallion, Alope."

"Why?" Alope asked.

"I must fight a duel of stallions with Ponce, the son of Ponce, and the only stallion among my mother's horses is too old to fight," Geronimo said.

Alope asked, "Why must you fight such a duel with young Ponce?"

"He gave me the lie!" Geronimo said angrily. "I killed three deer with my bow and arrows. Ponce said I found them dead!"

"Twelve-year-old boys are not supposed to be able to kill deer," Alope said.

"I did!" Geronimo insisted.

"I believe you," Alope said. "But these duels are dangerous. You know the elders have forbidden them."

Geronimo patted the stallion's cheek.

"If the elders do not know a duel is being fought," he said, "they can do nothing."

"And if my uncle's war horse is killed," Alope told him, "he'll stake you out on an ant hill and let the ants devour you."

Geronimo said, "I'll gladly accept any punishment after I have fought this duel, but I must fight!"

"What if you are killed?" asked Alope.

"I won't be. Among all his father's horses, the son of Ponce shall find no stallion to equal this one, and I am a much better rider!"

Alope said, "My good sense bids me run and get my aunt, but my heart tells me to speed a warrior on his way. I'll not tell, but I'll tremble for what will happen to you should my uncle's war horse be killed or hurt."

Geronimo slipped the tether rope, grasped the rein, and vaulted happily to the back of the mighty horse. Though the stallion wanted to gallop and Geronimo burned to test the speed and fire of such a mount, he held him to a walk. There was a fight coming up. The stallion must go into it rested.

At the same time, it was a glorious feeling just to be on such a stallion. All Apaches could ride, but few were master horsemen. Geronimo had started riding the village colts when he was so small that it was necessary to lead his mount beside a boulder or stump from which he could scramble onto its back. He seemed born to ride. Not half a dozen men in the village could stay on the back of Delgadito's war horse. But Geronimo was riding him.

After twenty minutes the Indian boy looked down on the secluded swale where the duel would be fought. He and Ponce had chosen a battle ground far enough from the village so that the elders would be unlikely to interfere. Young Ponce was waiting there with one of his father's best horses, a fiery bay that had already slain a half dozen rivals.

Though the elders knew nothing of the duel, a crowd of boys ringed the chosen arena. They were tense with excitement, but they did not yell and shout as white boys would have. And all stood far enough away so that they could escape if either stallion charged toward them.

As Geronimo rode down the hill, Delgadito's war horse caught scent of the other stallion and screamed his challenge. Ponce's bay answered, and the two stallions rushed each other. Quickly Geronimo planned his battle.

Such duels were a common way for Apache boys to settle arguments. They often resulted in the death of a horse, a rider, or both. When they did, it was usually the rider's fault. Geronimo planned on using his riding skill to make a fool of Ponce, and he intended that nobody should get hurt.

Just as it seemed certain the two stallions must close with each other, Geronimo turned Delgadito's war horse so expertly that they passed within inches. At this wonderful display of riding skill, an excited murmur of admiration rose from the watching boys.

Geronimo turned back, this time wheeling right in front of Ponce's angry stallion. He swerved to come in to the side. Ponce's bay reared and pawed the air with skull-crushing front hoofs. The watching boys gasped. But just as it seemed certain that Geronimo would be killed, he leaned over and escaped by the width of a hair.

Suddenly, to Geronimo's vast surprise, Ponce wheeled his stallion and galloped away as fast as his bay could run. Deciding to chase him on Delgadito's war horse, Geronimo was even more astonished when a shrill whistle split the air.

The war horse whirled and trotted obediently to—Delgadito himself! For the first time Geronimo noticed that the watching boys had disappeared too. He alone had been so interested in the duel that he had failed to see Delgadito come. The chief's eyes blazed with anger.

"Why do you fight a duel of stallions?" he demanded.

"The son of Ponce gave me the lie!" said Geronimo, sitting erect on the war horse. "I killed three deer with my bow and arrows! Young Ponce said I found them dead!"

"Come with me!" commanded Delgadito.

He turned toward his gray hunting horse, which was rein-haltered near by and which had a buck strapped behind the saddle. Without a word or a backward glance the tall chief mounted and rode at a walk in the direction of his wickiup.

Though he shivered inwardly, Geronimo did his best not to show it as he followed. Nor was he sorry that he had stolen the war horse. He had acted as a warrior should; he would take his punishment like a warrior.

When they reached the wickiup, they dismounted and Delgadito tethered both horses. Then he removed his bow and quiver of arrows from the hunting horse, took a single arrow from the quiver, and gave the arrow and the bow to Geronimo.

"Killer of deer, I would see you shoot," the chief ordered.

Geronimo fingered the unfamiliar weapon. "What target?"

Delgadito nodded at a pine about twenty yards away. "The knothole."

Geronimo nocked the arrow, raised the bow, and needed every ounce of his strength to draw it. This was a man's weapon, with a much heavier pull than the bow he had made for himself. But he did not shoot until he knew he was on target.

The arrow's shaft quivered as its copper point bit deeply into the knothole.

Delgadito said, "I saw you ride, and now I have seen you shoot. You told no lies. When the sun has risen three times more, I will lead a raid against the Papagoes, for we should steal more horses. You will ride with us."

Delgadito turned and entered his wickiup to indicate that Geronimo was dismissed. But for a full two minutes the dazed youngster did not move. At last, at long last, his fondest dream was coming true.

He was to be a true warrior.

Raiding the Papagoes

Three days later, at sunrise, an excited Geronimo sat nervously on his mother's aging stallion and waited for the raiders to start. Besides Delgadito, who was the leader, and Geronimo, there were four braves named Nadeze, Sanchez, Tacon, and Chie.

The dome-shaped wickiups where the villagers lived were softly beautiful in the early morning light. Here and there the embers of last night's cooking fire—for in this fine spring weather the Apaches did most of their cooking out of doors—glowed like a star fallen to earth. But except for the sentries who had been up all night, and the raiders about to set forth, the village slept.

When all the raiders were mounted, Nadeze and Sanchez left the others. Presently they returned driving a dozen loose horses among which was a beautiful spotted apaloosa. This horse had belonged to a shaman, or medicine man, of the White Mountain Apaches and had been taken from him in a night raid.

It was always necessary to have extra horses when going into enemy country for any reason. They could serve as remounts. If there was no other food they could be eaten, or they could be traded if there were any opportunities for trading.

But Geronimo wondered why Nadeze and Sanchez had included the apaloosa. The spotted horse was famous throughout the land. Even the Papagoes and pueblo-dwelling Zuņi knew him, and whoever saw him would surely send winged words to the shaman.

"Then a war party from the White Mountain Apaches will come to rescue their medicine man's horse," Geronimo thought. But he asked no questions. Surely Delgadito knew what he was doing.

Nadeze and Sanchez drove the loose horses on at full gallop, for the sooner the animals were tired the sooner they would be willing to stay with the rest and the less trouble they would cause. The other raiders rode out from the village more slowly.

An hour later they overtook Nadeze and Sanchez, and the driven horses, now too tired to run. They fell in at the rear and seemed satisfied to stay there. Geronimo felt a rising anxiety.

He had always imagined raiding to be a stealthy business. These men laughed, shouted, and gaily mimicked a coyote that moaned from a nearby ridge.

Presently lithe, slim Tacon challenged fat Chie to a race. Whooping at the tops of their voices, they were off. Geronimo stopped worrying. Delgadito was too experienced a raider to do anything foolish. If he let the warriors act as though there were no enemies within twenty miles, then there were none.

That night they camped on top of a rocky hill from which they could see in all directions, and they were careful to put all fires out as soon as darkness fell.

"Fire may be seen for a long distance on a dark night," Geronimo said to himself. "That is why they were put out."

The next morning the raiders rode on, and not until midafternoon did they make the slightest attempt to hide themselves. But when they finally halted under a cloud-ridden sky, there was a change in every man.

This was desert country, and they stopped in a cluster of rocky hills. Delgadito and Chie dismounted and climbed the tallest hill to scout from its summit. Soon they returned and told the others to dismount too. Tether ropes were slipped about the necks of the loose horses, which were now led by the raiders as all went on quietly.

A half hour later the raiders made a second stop in a dry wash. The banks of this desert creek bed were about four feet high and rimmed by cactus and palo verde trees.

Sanchez and Delgadito felled one of these trees with copper hatchets, cut off two stout chunks, and tied either end of a long rawhide thong to them. Then they stretched the thong as far as it would reach, and buried the chunks in the earth, at the bottom of the creek bed. Careful to place a gentle horse between two quick-tempered mounts, they tied all animals to this picket line. This done, all got their weapons and started up over the wash.

Geronimo ran happily for his own bow and arrows and followed. Suddenly Delgadito turned, put the palm of his hand against the youngster's face, and pushed so hard that Geronimo found himself seated in the bottom of the wash.

"Stay here to watch the horses," the chief growled.

"But I'm a warrior too!" Geronimo protested.

Delgadito growled again, and amused smiles flitted over the lips of the others. The raiders melted into the desert.

Flames of anger scorched Geronimo's cheeks, and rage ate at his heart. He had a fierce desire to pursue and kill Delgadito in revenge for being knocked down. But he knew that he must obey his chief. And he found it much more satisfactory to be guarding warriors' horses than to be playing children's games in the village.

Geronimo pillowed his back against a boulder and for a while never took his eyes from the horses. Then it began to seem foolish to watch them at all. The animals were standing quietly, and the idea that an enemy might come into the creek bed seemed unlikely. Presently Geronimo went to sleep.

Some time later he awakened. At first he thought he had been disturbed by the deepening clouds and a feeling that rain would soon fall. Then he peered down the wash.

Two nearly naked Indians carrying war clubs were stalking the horses and were only about forty yards from the nearest animal. Their clubs, the way they wore their straight black hair, and their tattooed faces stamped them as Papagoes. It was plain to see that they intended to steal the horses.

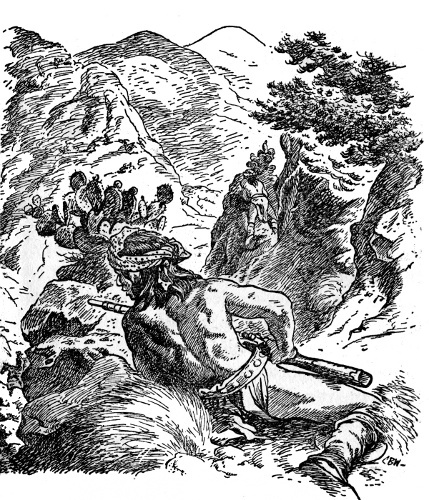

When he was certain that neither Papago was looking in his direction, Geronimo slung his quiver of arrows over his back. Taking his bow in hand, he crawled swiftly to and under the nearest horse.

The horses were not in an even line, but all stood perfectly still because they were interested in the Papagoes, and their legs formed a rough tunnel. Geronimo crawled down it. Reaching the last horse, he stopped and licked dry lips.

He wished Delgadito or any of the others were there. It was one thing to dream of becoming a warrior and quite another to face the enemy. What should he do now? Then the Papagoes saw him, raised their clubs and rushed forward, and there was only one thing he could do.

Geronimo plucked an arrow from his quiver, nocked it, drew his bow, took careful aim at the nearest Papago, and shot. The Papago was hit squarely in the heart. The only sound as the man fell was a jarring thud when he struck the ground. His companion turned to run.

Forgetting to nock another arrow, Geronimo crawled weakly from beneath the horse and for a few minutes sat shivering. Then he remembered that, though he was still a boy, he would soon be not just a warrior but an Apache warrior. Forcing himself to rise, he walked over to look at the dead Papago, and told himself that he was glad he had put an end to another enemy of the Apache. But he was just as happy that he had not killed the second Papago too.

Before long a black horse, flanked by a gray and four bays, jumped down into the wash, ran across it, and stopped. They stared back in the direction from which they had come, and the tethered horses raised their heads to stare too. Geronimo thought that the black was a wonderful stallion and was surely stolen from some Mexican rancheria because no Papagoes bred horses so fine.

Now more horses came galloping over the desert until there was a herd of about eighty milling around in the wash. For the most part they were scrawny Papago ponies. But Geronimo saw one more fine stallion, a dark gray with black spots.

Riding stolen ponies, which they guided without help of saddle or bridle, Delgadito and his raiders were on the heels of the last horses. As their mounts jumped into the wash they slid off. Delgadito made his way to Geronimo and looked down at the dead Papago.

"How is this?" the chief asked.

"He would have stolen our horses," Geronimo replied.

"Was he alone?"

"There was another," the boy admitted. "I did not kill him."

"You should have," Delgadito scolded. "But come now and mount."

Geronimo ran with him to the picket line and mounted his mother's old stallion, then he was astounded to see Delgadito take time to strip saddle and bridle from his own horse and put them on the apaloosa. Geronimo marveled. This was enemy country and, when the Papagoes discovered that some of their horses had been stolen, they were sure to launch a hot pursuit. But Delgadito seemed as calm as he had ever been at home in his own wickiup.

Mounting the apaloosa and whooping at the top of his voice, Delgadito charged the herd. The other riders took off, one after another, and drove the horses full speed straight north. This puzzled Geronimo. Finally he rode over to talk with Nadeze.

"Why do we go north?" he asked. "Our home is almost due east."

"Worry not and question not," Nadeze said coolly. "Look and learn."

Always at full gallop, Delgadito was racing from one end of the line to the other. The apaloosa already had run at least six times the distance any other horse had traveled.

About an hour and a half later Delgadito caught his own horse and transferred saddle and bridle from the apaloosa to him. The exhausted apaloosa staggered ten feet to stand with head drooping. Geronimo finally understood.

Beyond any doubt, Papago trackers were already on the trail of Delgadito's Mimbreno raiders. They could not fail to find the weary apaloosa and they would know its owner was the shaman of the White Mountain Apaches. They would also see that the stolen horses had been started northward, toward the home of these Apaches. Thus the Papagoes would think that they had been raided by men from the White Mountain tribe and they would seek revenge on them, rather than on the Mimbreno Apaches.

"We have a wise chief," thought Geronimo, as Delgadito's plan became clear to him.

Just then Delgadito said, "Chie, continue northward with thirty of the more worthless horses. Leave a plain trail, as though we were stricken with panic. But drive the horses back and forth so it will appear as though there were many more than thirty. Run as soon as you see pursuers."

Chie nodded, and the rest of the men started dividing the remaining horses into smaller groups.

"Why do we do this?" Geronimo asked, riding along beside Nadeze.

"It is easier to hide the trail of a small group of horses," said Nadeze. "And the Papagoes will find it much more difficult to track us since we will take each herd in a different direction before swinging back to our village."

"Do I drive some?"

"You are too anxious, stripling." Nadeze was far more respectful since Geronimo had slain the Papago. "You will ride with one of us."

Suddenly the rain clouds which Geronimo had noticed earlier loosed an earth-battering torrent. The raiders smiled. Usan, god of their tribe, had indeed blessed them. Though the Papago trackers would certainly find the apaloosa, they would never discover where the rest of the horses had gone after a storm such as this one.

Driving all the horses ahead of them through the pouring rain, the raiders turned homeward.

In bright sunlight next day, the stolen Papago horses cropped grass on the slope opposite Delgadito's wickiup. Geronimo listened anxiously while Delgadito, as was the right of a chief who led a raiding party, divided the plunder.

The leader reserved twenty horses for himself, and the twenty he chose included the two fine stallions. Then he gave smaller numbers of horses to the four men who had gone with him. The number each received depended on how hard he had worked to make the raid successful. Next came a just share for all families who had no one to steal horses for them.

Geronimo's heart sank as the horses were given away. He had hoped to get something for himself, but now the only horses remaining were a dozen or so fit only for the cooking pot. Delgadito declared them as such. Then he announced, so that all could hear:

"I give part of my portion, the black stallion and the gray stallion with black spots," he swung to Geronimo, "to an Apache youth who deserves them because during this raid he behaved like a warrior."

For a moment Geronimo was too surprised and delighted to move. Then he tilted his head, squared his shoulders, and went proudly forth to claim his prizes.

It was spring in the year 1846, five years after Geronimo's first raid. Ten miles south of the Arizona-Mexico border, Geronimo sat silently on the summit of a low hill. His knife was on his belt. His muzzle-loading rifle, powder horn, and bullet pouch were in easy reach. A red blanket was draped over his body, which was naked except for breech cloth, moccasins, and the warrior's headband that bound his black hair.

Two young warriors, Zayigo and Pedro Gonzalez, sat beside him. Both were older than Geronimo. Yet both had chosen to let the seventeen-year-old warrior lead this raid into Mexico because of his cunning and courage.

Now they were a little uneasy because of their leader's silence. Usually Geronimo loved to talk, and he was already a leading orator among the Mimbreno Apaches. When he was least talkative, he was most dangerous. Finally Zayigo said impatiently:

"We sit beside the youngest Mimbreno Apache ever to become a member of the Council of Warriors. Yet he sulks like a scolded child. It ill befits him."

"Aye," Pedro Gonzalez agreed. "Since leaving the Mimbreno village, Geronimo, you have smoldered like a fire that is not quite able to burst into flame. Is it because some warriors spoke against you when they met to determine whether you might be admitted to the Council?"

"I care not who speaks against me," Geronimo said sourly. "Any who consider me unworthy of being a Mimbreno warrior I'll fight gladly."

"Those who did not want to admit you to the Council of Warriors never questioned your bravery or your skill in battle," Zayigo said quickly. "They said only that you are reckless and headstrong, and that trouble goes where you do because you never reckon the odds."

"There are some Mimbreno warriors who have the cowardly souls of Mexicans," Geronimo grunted. "And I do not mean that you are a coward, Pedro."

Pedro Gonzalez said quietly, "Mexican I was once. Apache I am now."

That was true. Captured in Mexico when he was five years old, Pedro had been adopted by an Apache family. He had taken so readily to Apache ways that he was now one of their finest and fiercest warriors. He spoke again:

"If you care not because some spoke against you, what is the trouble? It is no pleasure to go raiding or anywhere else with one who does little except stew in his own anger."

Geronimo said bitterly, "Ne-po-se was one of the men who spoke against me."

"The father of Alope does not like you," Zayigo said. "But that is no news in the Mimbreno village. Ne-po-se does not care to have Alope marry a mere warrior when it is possible that a chief will offer five horses in exchange for her."

For a moment Geronimo did not answer. For five years he had watched Alope become lovelier each year. Her image accompanied him wherever he went by day and haunted his dreams by night. He was as deeply in love as a young man can be.

He said finally, "When I became a warrior in full standing, I went to Ne-po-se and asked for Alope. He sneered at me, and said to come back when I could offer ten horses for his daughter's hand."

"Ten horses!" Zayigo said in astonishment. "That is unheard of, even for such a bride as Alope! What do you intend to do?"

"Pay for my bride what she is worth," Geronimo said. "That is why we are in Mexico, where there are plenty of horses for the taking."

He spoke more easily, for talking about his troubles had made them seem less. Zayigo and Pedro Gonzalez smiled, their white teeth flashing in the darkness.

"Now you talk as the leader we hoped we were following," Pedro Gonzalez said happily. "Of course there are plenty of horses in Mexico. And when it comes to stealing horses, no warriors are more clever than Geronimo. You shall gain the price of your bride."

"I shall have the price or I shall not return to the Mimbreno village," Geronimo vowed. "And I know we shall return for we go against Mexicans.

"I think it must be true that something in the food they eat or the water they drink turns the marrow of Mexican men's bones to jelly as soon as they become men. Captive Mexican women fit very well into our tribe, as do children if taken young enough. The men do little except tremble with fear, and that is why it is better to kill than capture them."

Pedro Gonzalez laughed joyously. "It is long since I have fought Mexicans. Let us hope this is a good fight."

They curled up in their blankets and slept. The night was still black about them when they rose to go on. Traveling at a loose-legged gait that covered the ground with amazing speed, they were many miles from their camping place when the sun rose. They stopped to nibble parched corn from pouches that hung at their belts, rested less than five minutes, and went on.

Geronimo, who had been this way many times and who also had a splendid sense of direction, led the others through steep-walled canyons and over brush-grown hilltops. By midafternoon they were looking from the top of a hill down on the rancheria they intended to raid.

The house and other buildings were built of adobe, or sun-dried brick. To one side were extensive corrals made of poles that had been laboriously hauled from some river bottom or other where trees were plentiful. There were about fifty horses in the corrals.

The three Apaches crouched in the brush and bided their time. They were heedless of the sun that burned down upon them. Thirst that would have driven a white man mad bothered them not at all. They were trained to endure thirst.

An hour before dark, several Mexican riders came with a herd of forty horses. They put them in the same corral where the fifty were already confined, and turned their own saddle mounts in with them. Two more riders came, stripped saddles and bridles from their mounts, and shut them in the corral. Then all the Mexicans went into the house.

Night fell before the three Apaches stirred. Geronimo gave his orders.

"Zayigo and Pedro, keep those in the house from coming out. I go to the corral."

Geronimo slipped away in the darkness. He could no longer see the corral, but his sense of direction was so sure that he went exactly to it. The Mexicans had draped their saddles over the top rail and hung their bridles on the saddle horns. Taking no saddles, for all three raiders were expert bareback riders, Geronimo looped three bridles over his shoulder and entered the corral.

The horses snorted in alarm when they got his scent, then wheeled to run to the corral's far side. Geronimo did not hurry even slightly, for in the first place any quick move would frighten the horses. In the second place, with Zayigo and Pedro Gonzalez watching the house, he was not afraid that the Mexicans would come. In the third place, Geronimo had done this so many times that he knew exactly how to go about it.

Presently he backed a group of horses into a corner of the corral. Geronimo caught one, held it by looping the reins of one of his three bridles around its neck, and bridled it. He mounted.

At that moment, a stallion screamed.

The door of the house was flung open. But when Zayigo's rifle spoke, the door was slammed shut quickly. Still refusing to hurry, Geronimo caught and bridled two more horses. Sitting his own mount, and holding the reins of the other two, he whistled shrilly.

Zayigo and Pedro Gonzalez appeared out of the darkness. Not speaking, for each knew exactly what he must do, they mounted the two bridled horses. Geronimo opened the gate and the three drove the herd through.

There were hundreds of other horses grazing on the vast acreage of the rancheria. But this was the only herd kept near the house and the raiders had been careful to take all of them. The rest were miles away at other water holes. Even if the Mexicans recovered their wits immediately, they would still need hours to get more horses and launch any kind of pursuit.

The raiders drove their herd toward Apache land at a leisurely walk.

On their return Geronimo gave Ne-po-se twenty fine horses. It was a gift so dazzling that even Mangus Coloradus, giant chief of the Mimbreno Apaches, came to inquire about it. And Ne-po-se could no longer forbid Alope to marry the brave young Geronimo.

Several thousand people lived in the Mimbreno village. But since most Apaches liked plenty of room between themselves and their neighbors, the village was spread over several hills.

Geronimo and Alope, however, built a fine wickiup very near the house of Geronimo's widowed mother. Alope decorated it with pictures while Geronimo brought the skins of elk, deer, antelope, puma, and other creatures that fell to his hunting arrows. There were no bear skins because bears are sacred to Apaches.

The following twelve years were probably the only truly happy ones Geronimo ever knew. A daughter came to live in the wickiup, then a son, then another daughter. It was a full and wonderful life for all.

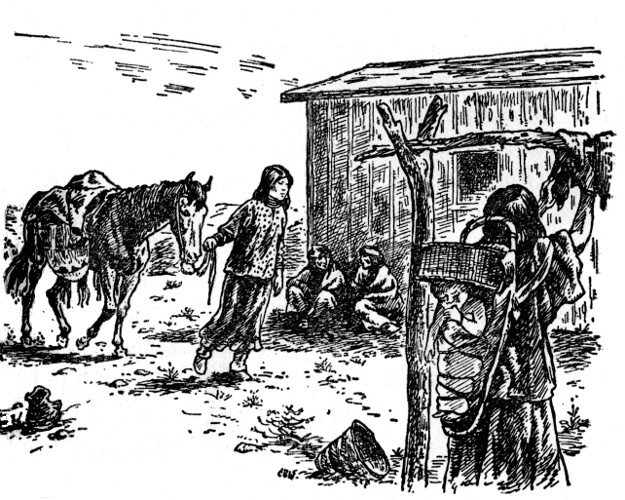

Again it was spring, the spring of 1858, and almost the entire village of Mimbreno Apaches was on the move.

Twenty or more youngsters, who couldn't contain their own bubbling spirits and wouldn't restrain their lively ponies, led the main column by half a mile. Next, riding his immense war horse and surrounded by his sub-chiefs, came Mangus Coloradus himself—a giant of a man and a great leader. Immediately behind this group were more than three hundred pack horses and burros. Their packs bore tanned skins, fruit of the saguaro cactus, edible roots of the mescal plant, and other trade goods.

The pack train was guarded by warriors who rode on either side. Far enough behind so that they would not be bothered too much by the dust of the pack train, came the remainder of the warriors, the old people, and the women and children. All were mounted. Some of the smaller children rode four or five to a pony. They were going on a holiday of the happiest sort.

Though the Apaches were usually at war with the Mexicans, they had arranged a peace so that they might have their great annual trading party, or fiesta, in Mexico. Most of their trading would be done in the town of Casas Grandes, deep in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. But before reaching Casas Grandes they intended to stop and trade at a smaller town which they called Kas-Kai-Ya.

Two and a half miles short of town they halted and set up camp. This was a simple enough business. Most of the Indians just cast their blankets down on the ground and arranged a fireplace. Some cut green saplings and thrust the thick ends in the ground to form a circle. Next they bent the tops together and held them with buckskin thongs. Then they thatched the walls with deer skins or blankets.

Geronimo started building such a wickiup for his mother, Alope, and his three children. His two daughters, ten and five, and his seven-year-old son tried so enthusiastically to help him that the wickiup never would have been built if Alope hadn't taken charge.

The Apaches had not stopped so far from Kas-Kai-Ya because they were afraid of the Mexicans. But, though Mexican women might roam at will in Apache villages, no Apache woman would think of showing herself in a Mexican town. Besides, trading was a man's business.

Leaving enough warriors to protect a peaceful camp, the eighty men who were going in town to trade set out, led by Mangus Coloradus himself. They took only thirty horses, twelve of which were laden with trade goods. The rest of the trade goods and the pack horses and burros were saved for trading in Casas Grandes.

Every warrior except Geronimo had a hidden knife. Some carried hidden pistols, and a few had carbines, or short rifles, thrust inside their breeches. To enter the town openly armed would surely provoke a fight, and a fight would spoil the holiday. But even though they were supposedly at peace, no Apache ever trusted any Mexican and no Mexican ever trusted any Apache.

Geronimo carried only a buckskin pouch filled with yellow metal that, to him, hadn't the slightest value. Made into arrow or lance heads, it blunted on almost any target. It was too heavy for hair or ear ornaments, and useless to the Apaches except as playthings for the children. But the Mexicans, who called the metal oro—gold—prized it greatly.

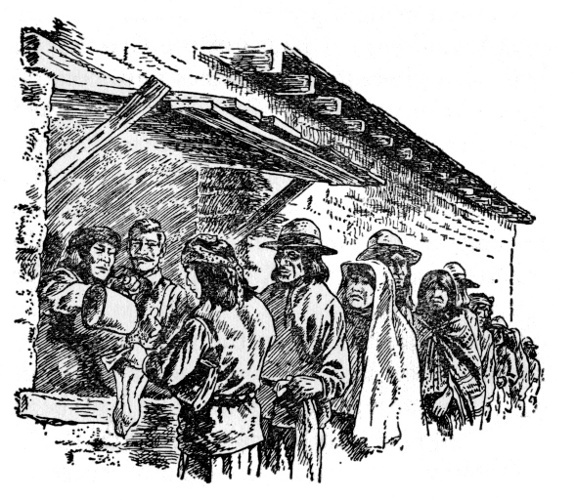

The traders reached the sun-dried brick wall enclosing the town of Kas-Kai-Ya and found a squadron of rurales drawn in formation across the gate. All these soldier police were mounted and armed, and their snapping black eyes were filled with hatred for Apaches. As Geronimo knew, there was good reason for this hate. Apaches had raided too long, too often, and too successfully in Mexico to win any friendship from rurales whose duty it was to stop them. Mangus Coloradus addressed the uniformed officer:

"Buenas tardes, Seņor Rurale. We would trade."

The officer made an effort to stare Mangus Coloradus down, and when he couldn't do it, flushed angrily. But he replied civilly:

"Buenas tardes, good afternoon, Seņor Apache. You may enter."

The rurales drew aside, let the Apaches through the gate, and then reformed across it. The Apaches braced themselves to meet the horde of peddlers that screeched and squawked down on them.

Geronimo was confronted by a lanky man whose only garment was a tattered serape, or blanket-like robe, that was draped over one shoulder and pinned at the sides with thorns. His hair looked as though it hadn't been combed in years, his beard was as tangled. His body was dirty. His eyes were both cunning and humble.

In sharp contrast were the fierce eyes of a golden eagle that the Mexican had imprisoned in a wooden cage. In spite of broken and bedraggled feathers, the eagle still looked royal. The Mexican lifted the cage.

"See?" he whined. "See, Seņor Apache? Grieved though I must be to part with anything so precious, this noble bird is yours for only three horses."

Geronimo brushed haughtily past the man and walked on. The peddler called anxiously, "Will you give me some mescal?"

Geronimo's eyes expressed his disgust. If wild things were not meant for the wilds, the god, Usan, would not have placed them there. They might be hunted for food but never should any be imprisoned.

"Some tobacco?" the eagle's captor wailed.

Geronimo turned, glared, and the Mexican scurried away. Geronimo continued his unhurried walk. Kas-Kai-Ya was truly remarkable, largely, Geronimo thought, because so many people could live in such a small area. They were so crowded that Geronimo wondered how they kept from suffocating each other.

He saw a man lying with his head on a chunk of adobe, the same sun-dried brick from which the town walls and all the buildings were fashioned. Suddenly the man leaped up and began to scream. Other Mexican men, women, even children at once started to scream or shout as loudly as they could. The clamor was deafening.

The amazed Apaches halted and gaped. After a bit, assuring himself that this senseless yelling must be a sickness suffered by those who allow themselves too little room, Geronimo went on.

Presently he halted beside a Mexican who had a basket supported by a ragged rope over one shoulder. The basket was divided into compartments and filled with glass beads that were separated according to color.

The beads were so fascinating that Geronimo scarcely knew that the horrible din had quieted.

He caught up a half dozen assorted beads and one by one put them back in the proper compartments. He took out his pouch of gold. But though he yearned for the beads, and would gladly have given all his gold for them, he was too good a trader to offer everything at once. Geronimo dropped two small nuggets onto the palm of his hand and held them out.

"No," the bead vendor refused.

But excitement made him breathe hard, and he could not take his eyes from the pouch. Geronimo gave him two more nuggets. The Mexican gasped and Geronimo thought he was once more refusing. Recklessly he poured half the gold into the bead vendor's palm. The Mexican moaned, slipped the basket from his own shoulder and hung it on Geronimo's, cupped the gold with both hands, and ran.

Geronimo dropped the still half-filled pouch of gold into the dust and forgot it. He noticed for the first time that his comrades were making their way toward the gate. Trading had been brisk. The Apache trade goods were gone and each warrior had at least a double handful of knickknacks. The rurales drew their horses aside and let the departing Apaches through the gate.

The Indians started back to their camp. But when they were halfway there Mangus Coloradus halted suddenly. A split second later, every warrior was alert. From a brush-grown arroyo, or gully, came the hushed voice of Pedro Gonzalez, one of those who had stayed behind.

"This way."

The eighty melted into the arroyo as quietly as eighty quail might slip away from an approaching hunter. They found Nadeze with Pedro. The wives of five of the men who had gone into town and the wives of four who had stayed behind were there also. And two girl children. The faces of all showed shocked, numbing grief. But the eyes of all, even the two children, blazed with fury.

"Some rurales came!" Pedro snarled. "I know not from where! But they outnumbered us two to one. And when we warriors would have fought rather than let them enter the camp, they reminded us that this is a time of peace! They said they wished only to trade and talk, but once among us they attacked without warning! We slew many, but our horses, our arms, our trade goods, are now theirs! Of those men, women, and children who stayed behind, we alone live!"

"Where are the rurales now?" asked Mangus Coloradus.

"In what was our camp, awaiting your return," Pedro said.

Mangus Coloradus said, "When Apaches do not make fools of Mexicans, the Mexicans seem determined to make fools of themselves. The rurales must have known that some escaped, and that we would be warned. They should have ambushed us as we left the gates of Kas-Kai-Ya."

Sadly he thought of all who had been killed. Then he added "I will take the wives of our brave men and these two children with me, and I will hold myself responsible for their safety. Of the rest, each seek a different path and hide his trail. We will meet at the place we have chosen to be our rendezvous."

A moment later, the arroyo was empty of Apaches.

Light from a thin slice of moon glanced from the Bavispe River, stole through thinly leaved trees, and painted a lichen-crusted boulder with moonbeams.

But the moonlight made not the faintest impression in the grove of thick-limbed, heavy-trunked trees on the river's bank. Beneath the trees it was black enough for devils to dance. But any devils who might have been there would have been frightened away by the Apaches who had come to Mexico in peace but who knew now that there must be war. This grove was their appointed rendezvous should anything go amiss while they were trading.

Geronimo sat as though he had lost everything that made him alive but was still not dead. He knew dimly that Mangus Coloradus was talking in low tones with men whom Geronimo was too dazed to recognize.

The Mimbreno chief said, "We must go to our village."

"And leave our dead?" The question was laden with heartbreak.

Mangus Coloradus said, "We are deep in enemy country, with few arms, no food, and no horses. Is there another way?"

"I will not go," Nadeze said firmly.

"Then you will not return to meet again those who massacred our people," said the chief.

"Return?" Nadeze was puzzled.

"We will come again," Mangus Coloradus promised, "but with warriors only."

"Ha!" Nadeze snarled like an angry puma. "If my dead know that, they will forgive me for leaving! I must go and tell them!"

Others announced their intention to return to the encampment for one last visit with their dead.

"Go we may, but we must go cautiously and we must not linger," Mangus Coloradus said. "The rurales may still await us there. If they do not, the night is our friend. And we must ask our friend to shield us while we travel far."

A clear thought penetrated Geronimo's numbed brain. At the time when the massacre must have occurred, the people of Kas-Kai-Ya had set up a deafening racket. Why, if not to make it impossible for the warriors in town to hear rifle shots?

The thought faded and Geronimo was again a live body with a numbed brain and sick soul. He understood dully that they must return to their village, but that first they would have one last visit at the encampment. He rose only because the others did, and started out of the grove.

They found and traveled the trail to the Apache encampment. It was a bold move and, under a lesser chief than Mangus Coloradus, might have been disastrous. But the Mimbreno chief had rightly decided that Mexicans gauged Apache hearts by their own. If such a disaster had stricken Mexicans, the survivors would never have dared show themselves on the trail. Neither would they have visited the scene of the massacre.

When the angry and grief-stricken Apaches reached the encampment, they found that the rurales had left. The moon was merciful. The crumpled figures that lay all about seemed like so many sleeping persons.

Geronimo sought the wickiup where he had left his family.

He stopped suddenly. Alope lay full length before him, head turned and cheek resting on her right hand. Her long black hair tumbled at her side. Many times had Geronimo watched her sleep in just such a fashion, and now she seemed asleep. But she did not wake.

Geronimo's mother had fallen at the entrance to the wickiup, and the children were near. The two little girls had embraced when the Mexicans overtook them, and had fallen with their arms still about each other. The boy was at his sisters' feet. His right arm was stretched toward them, and he still clutched the rock which he had intended to throw at the treacherous Mexicans.

Geronimo was unaware of the hand that touched his arm, until Mangus Coloradus said gently, "Come with us, brother."

Geronimo responded like an obedient dog. He felt no grief, no shock, no pain, for he was too numbed to feel anything. He knew he must follow only because he had been told that he must.

By sunrise the Apaches were many miles from the scene of tragedy. Mangus Coloradus had led them over the roughest and rockiest places. They had waded streams wherever streams flowed and done everything possible to hide their trail.

At last Mangus Coloradus called a halt and sent some out to hunt while he told others to build a smokeless fire from dead wood. One by one, the hunters returned. Since a shot from a gun would have attracted attention, the game had been brought down with thrown rocks or knives. Their bag consisted of some jack rabbits and a crippled peccary. They ate, rested, and went on.

Geronimo remembered nothing of the flight. On reaching the village, he went first to his mother's wickiup. He entered, but at once ducked out again and sought his own house. Slowly the fogs faded from his brain. He discovered that he still carried the basket of beads for which he had traded half a pouch of gold in Kas-Kai-Ya.

He had not realized, that night while the thin moon lighted the scene of the massacre, that the beloved people upon whom he looked were dead. Nor had he understood since. But he knew it now.

Geronimo plunged into his wickiup and sought his store of weapons. Shotguns, rifles, muskets, powder, shot, knives, hatchets, lances, bows, and arrows were carried a safe distance from the wickiup and put carefully down. The basket of beads was placed near them.

Then Geronimo strode to a nearby fire. Catching up a burning brand, he fired the wickiup he had shared with Alope, then cast the brand against his mother's house. He turned his back on the burning wickiups. Like his old life, they would soon be ashes. But there would be a new life, he told himself. A life of revenge!

Pedro Gonzalez was attracted to the fires, and Geronimo asked him, "Do you have weapons?"

"Bow and arrows, a knife, a lance, a hatchet."

Geronimo indicated his own store. "Choose what you will."

Pedro's brows arched in surprise. "You make gifts of such?"

"I give a weapon to whoever will ride with me and meet the rurales who murdered our people."

"I will ride, but only when Mangus Coloradus says to. He is still chief."

"Coward!" Geronimo spat.

Pedro's face tightened with anger, and he drew his knife. Geronimo grunted contemptuously and snatched at his own knife. Before either could make a thrust, Mangus Coloradus stepped between them.

"What insanity is this?" the chief thundered.

"I offered him his choice of weapons if he will return and fight the rurales!" Geronimo flared. "He will not go!"

"I will!" Pedro snapped. "But I wait until Mangus Coloradus leads!"

Mangus Coloradus whirled on Geronimo. "Have you turned fool?"

"I go to fight the murderers of my family," Geronimo said flatly.

"None of us has forgotten our dead," the chief replied. "We will go to avenge them, but to do so we must not only fight the Mexicans. We must defeat them. To defeat them, we must plan."

"Plan?" Geronimo inquired.

"We will seek Cochise, chief of the Chiricahua Apaches, and Whoa, chief of the Nedni," Mangus Coloradus said gravely. "We will ask their help. Then we will prepare. And then we will ride!"

All fires in the camp near the Bavispe River had been extinguished before sundown. Naiche, the young, tall, courageous son of Cochise, sat in the darkness with Geronimo. Geronimo spoke.

"An autumn, a winter, and a spring have been born and died since Mangus Coloradus sent me as his spokesman to ask the help of the Chiricahuas and the Nedni."

"I well remember your visit," Naiche said. "When you spoke, your words were fire that burned into my very heart. As I listened I knew that, if no other Chiricahua would follow you to Mexico and help avenge the massacre of your people, Naiche would."

"Soon the battle," Geronimo said.

"Soon the battle," Naiche echoed. "And at last I shall know."

"What shall you know?"

"Why so mighty a warrior as Geronimo, who owns many fine rifles, goes to fight Mexicans armed with a shotgun, a pouch of beads, a knife, and a lance."

Geronimo stared moodily into the darkness. Since fleeing from the encampment he had lived only to go back to Kas-Kai-Ya. But much time had been needed to plan an expedition large enough to attack the rurales there.

New weapons had been fashioned. Countless messages had been exchanged by Mangus Coloradus, Cochise, and Whoa, the three chiefs. The women and children of all three tribes had been taken to mountain retreats whose only approaches consisted of narrow canyons that a few warriors might defend. Then those retreats had been stocked with ample provisions and fuel.

Planning the campaign had been no easy task. Every warrior burned to go into Mexico and fight the rurales. Nobody wanted to stay home to guard the women and children. Nor would any warrior serve under any leader except his own chief.

Finally each of the three leaders had chosen his picked men. Mangus Coloradus included among his warriors all who had been at Kas-Kai-Ya. Now, with two hundred and fifty braves under Cochise, two hundred under Mangus Coloradus, and a hundred and fifty led by Whoa, they were well into Mexico.

Each of the three divisions kept apart from the others, but not so far apart that they would be unable to join forces when it was time for a battle. Naiche preferred to travel with the Mimbreno Apaches rather than with the Chiricahuas led by his father, Cochise. This was because of his great liking for Geronimo.

Geronimo said finally, "I took the beads from the Mexicans. Now I return them. That is only justice."

"Only justice," Naiche agreed. An owl hooted three times, and Naiche said, "The signal. A scout returns."

Geronimo said, "Come."

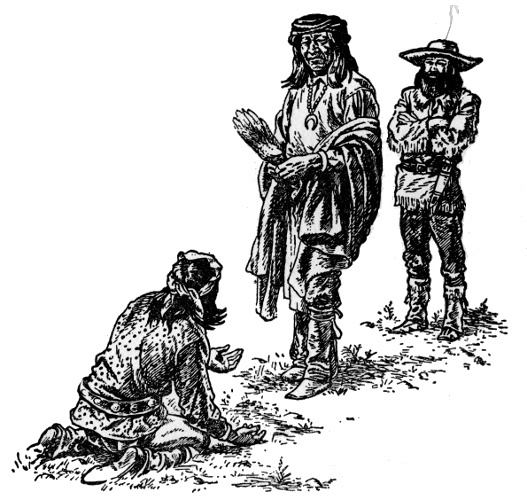

They rose and made their way to the camp of Mangus Coloradus. A short time later, dressed as a Mexican and driving a burro, Pedro Gonzalez loomed up in the darkness. He had been to Mexico in advance of the warriors to gather such information as he could.

Mangus Coloradus rose to meet him. "What saw you?" he asked.

"I saw rurales," Pedro said. "I even talked with them, since they thought me a Mexican. There are two companies of foot soldiers and two companies of horse soldiers. Among them are those who attacked us at Kas-Kai-Ya. But they are not now at Kas-Kai-Ya. They are at Arispe, in the Mexican state of Sonora and to the west of Kas-Kai-Ya."

Geronimo blurted, "Then we go to Arispe!"

"To Arispe!" Naiche echoed.

Mangus Coloradus asked haughtily, "Do warriors decide where the battle shall be fought?"

"I will fight the rurales who killed my wife, my mother, and my children," Geronimo said stubbornly. "If we must attack the people of Kas-Kai-Ya, that may come afterwards."

Naiche growled, "I fight beside my friend."

"We will all go to Arispe," Mangus Coloradus said. "We will start at once. For in truth we must fight the rurales who massacred our people."

"I shall tell Cochise," Naiche said.

Mangus Coloradus said, "Ask Cochise to inform Whoa. Tell both that we join forces before Arispe."

"I shall inform Whoa," Naiche promised.

Naiche disappeared in the darkness. The word spread like wind-driven wildfire, and warriors prepared to march. Nobody was mounted. Even with almost a year to make ready, there had not been enough time to capture war horses for everyone. Besides, so great a number of horsemen would be far easier to detect than foot soldiers, so nobody rode.

Geronimo felt in the darkness to make sure his knife was at his belt. In turn he fingered his powder horn, the pouch of beads, his parcel of jerked meat, and his parcel of parched corn.

He hung over his shoulder the blanket that served him as bed by night and clothing by day. Like all the rest of the warriors, he was going into battle wearing as little clothing as possible, and the blanket would be flung aside when the fight started. Taking his lance in his left hand, Geronimo carried his shotgun in his right hand.

Mangus Coloradus said, "Lead on."

Geronimo strode into the darkness. Partly because he knew Mexico so well, and partly because of his marvelous sense of direction, he had been appointed guide for the entire expedition.

In late afternoon of the third day following, they came before the walled town of Arispe.

They halted in a woods some five hundred yards from the town, and Geronimo's heart leaped as he stood beside Naiche. Again, in imagination, he saw his mother, his wife, his murdered children. A great joy rose within him at the knowledge that, only a short distance away, their murderers awaited. The Apaches had come upon Arispe so stealthily that the rurales couldn't possibly have fled. A battle was assured.

But their presence must be known soon, and when they were discovered they could expect action from Arispe. The sun was sinking when Naiche said:

"They come."

Eight townsmen bearing a white flag of truce left the walled town and walked toward the trees. Geronimo could not help admiring them. Eight Mexicans who approached any number of Apaches must be courageous.

"What would you do with them, brother?" Naiche asked, stepping closer to Geronimo.

"Hold them prisoner and force the rurales to come out to attempt a rescue," replied Geronimo. "Thus we may be sure of a battle."

"Their flag says they come to talk. It is not honorable to capture them."

"The rurales who slew our women and children at Kas-Kai-Ya were less than honorable too," Geronimo said grimly.

"That is true, but whether we capture or parley is for the chiefs to say. Let us hear."

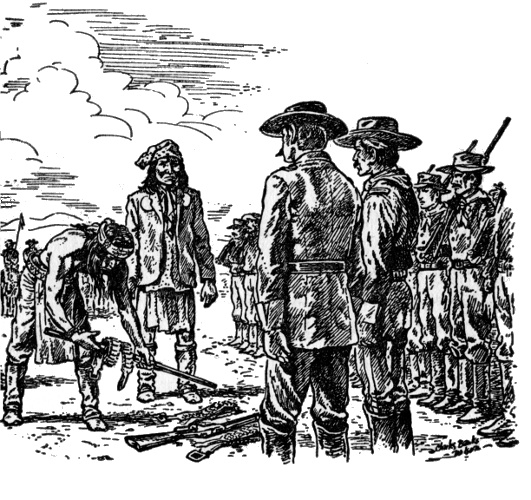

They made their way to where Mangus Coloradus, Cochise, and Whoa awaited the eight townsmen. No Apache stirred until the Mexicans were so near the woods that there was no possible chance of their running back into Arispe. Then Mangus Coloradus ordered:

"Capture them so the rurales must try a rescue."

Geronimo and Naiche remained with the chiefs, for they scorned to fight townsmen. But other warriors ran forward. The Mexicans halted and grouped together, each man with his back against a companion's.

Pedro Gonzalez, one of those attempting the capture, said in Spanish, "Submit and you will not be hurt."

"You come to kill!" a Mexican snarled, and eight hands flew to knives.

The encircling warriors drew their own knives. Near-naked Apaches ringed the Mexicans and it was over. Pedro Gonzalez came to the chiefs.

"We would have captured them, but they chose to fight," he said.

"It is no matter," Cochise shrugged. "The rurales will come now for revenge."

The next morning some of the soldier police did come. Twenty horsemen galloped toward the woods where the Apaches were hiding, fired wildly into them, and retreated without hurting anyone. That evening the Apaches captured a Mexican supply train whose leaders knew nothing of the powerful war party concealed near the town. Besides a store of food, the Apaches took many guns and much ammunition.

At ten o'clock the next morning, the rurales came in force. Two companies of infantry in battle formation advanced toward the woods where the Apaches were still hidden. Two of cavalry were held in reserve just outside the town walls.

Lying near the chiefs, with Naiche on one side and Nadeze on the other, Geronimo poured powder into the cavernous muzzle of his shotgun. He emptied the pouch of beads on top of it, tamped them in with cloth, and primed the gun. Naiche grinned, understanding at last.

Nadeze exclaimed, "There are the murderers of Kas-Kai-Ya!"

"So?" Mangus Coloradus said calmly. "What think you, Cochise? What think you, Whoa? These enemies slew Geronimo's mother. They slew his wife. They slew his children. Should Geronimo lead the first attack?"

"It is well," Cochise murmured.

"It is just," Whoa agreed.

Geronimo turned to Naiche. "Take fifty warriors and go unseen into that strip of woods we see from here. Wait until the enemies are past and we have attacked. Then charge them from the rear."

"I go, brother," Naiche said grimly. "Good hunting."

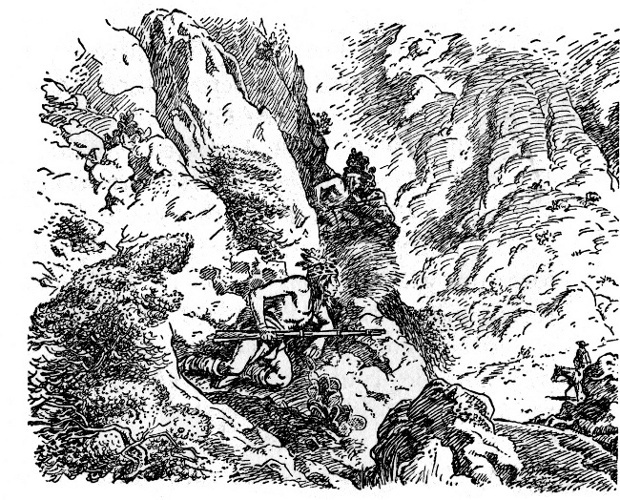

When the rurales were four hundred yards away they stopped to fire. Those in front kneeled so that those behind could shoot over their heads. Keeping his men hidden, Geronimo noticed that every weapon was discharged.

The rurales fired a second volley from two hundred yards and, as before, every weapon was emptied. Now, before they could reload, was the time to take them.

Shotgun in one hand, lance in the other, Geronimo sounded the Apache war whoop and raced out of the woods toward the enemy. The Mexicans worked desperately with their guns, but fewer than half reloaded in time. The remainder drew sabers and awaited the attack.

When only fifty feet separated Geronimo from the Mexicans, he leveled his shotgun, cocked it, and fired. The weapon spewed its glass beads forth, and half a dozen Mexicans fell. Flinging the now-useless shotgun from him, Geronimo leveled his lance and raced on.

He saw Naiche and his warriors swarm out of the woods to attack from the rear. At the same time he saw the Mexican cavalry charge to the aid of their hard-pressed comrades.

An officer, saber raised, rode straight at Geronimo, determined to ride him down. Geronimo sidestepped, thrust with his lance, brought the officer out of his saddle, and lost his lance in doing so.

Armed with only a knife, he awaited the next horseman. He dodged beneath the soldier's saber, caught the arm that wielded it, and pulled the rurale from his saddle. They rolled in a desperate struggle for the saber until a stray bullet, ricocheting across the battle-field, buried itself in the rurale's brain and he went limp.

Geronimo leaped to his feet, grabbed the saber, and went on fighting with it until he took another lance from a dead Apache.

Before sunset, the battered remnants of the rurales were trembling behind Arispe's walls. There would be wailing soon in some of the lodges of the Mimbreno, the Nedni, the Chiricahuas. But for every Mimbreno who had been slaughtered in the massacre of Kas-Kai-Ya, and for every warrior who had died before Arispe, two rurales lay dead on the field of battle.

Hidden by brush, Geronimo lay motionless on a hilltop and riveted his eyes on the scene below.

He was watching a man, one of the strange white men whom Geronimo had first seen when surveyors came to mark the boundary between the United States and Mexico. The man was leading four burros, each with a pack on its back. He was approaching a bluff.

Hiding behind the bluff, Geronimo saw two other white men on horses. When the man with the burros was near enough, the two leaped their horses in front of him. Leveling pistols, they said something Geronimo could not hear but was obviously menacing.

The man dropped his burros' lead ropes and raised both hands. The horsemen dismounted. While one continued to point his pistol at the man with the burros, the other rummaged through the packs. Presently he turned to his companion and exclaimed:

"Gold!"

"So you made a strike, Pop?" the other man asked. "Where is it?"

"'Twas just a pocket," the man with the burro quavered.

"Better not lie to us, Pop."

He who had searched the packs encircled the prospector's throat with one arm and held tight while the other man tied him. Then they built a fire and in it thrust a knife.

Grimacing, Geronimo stole down to where he had left his hunting horse. Apaches tortured prisoners, but only when they seemed to have important military information that they would not reveal. Even then, Geronimo had seen battle-hardened warriors turn away because they could not look upon the prisoner's suffering.

Mounting his horse, Geronimo heard the prospector shriek as his captors used the red-hot knife to make him tell where the gold mine was. He put his horse to a run because he cared to hear no more screams, and slowed only when he was out of hearing.

Not once did he even imagine that the prospector's body would be found by other white men and the killing would be considered as another terrible crime of Apaches.

After a while Geronimo stopped beneath another hill. He tethered his trained hunting horse. Bow in hand and arrow-filled quiver on his shoulder, he crawled up the hill so carefully that even a stalking cat would have been more noticeable.

Reaching the top, he looked down upon fifteen antelope. Very slowly, for antelope have wonderful eyes that notice the least move, he took two arrows from his quiver. One he nocked loosely in his bow, then laid the bow where he could grasp it instantly. To the feathered end of the other arrow he tied a strip of cloth. He raised this second arrow so that the cloth appeared above the grass, and waved it slowly back and forth.

Every antelope swung at once to gaze at this wonder. They turned their heads this way and that, stamped their hoofs, and blew through their nostrils. Then they let curiosity overcome caution and walked forward for a closer look.

When they were well within range, Geronimo dropped the arrow. In the same instant he seized and drew his bow and rose to one knee. The antelope whirled to run, but the hunting arrow Geronimo loosed caught a fat buck in mid-leap and brought him to earth dead. Geronimo dressed his game, tied it behind the hunting horse's saddle, and rode on to meet Naiche. He found his friend, who also had a fat antelope, waiting near the rocky spire where they had agreed to meet.

"I saw a great herd of antelope," Naiche announced. "I might have killed several, but I need only one."

Geronimo said, "I found only a small herd of antelope, but I saw three white men. I could not attack because they have guns and I carry only a bow and arrows. Two of the white men tied the third and burned him with a hot knife blade."

"All white men are crazy," Naiche growled. "And there are far too many of them in land that belongs to Apaches."

"There are not as many as there were," Geronimo pointed out. "It has come to my ears that they could not find enough Indians to kill, so they started a great fight among themselves. I have heard they call it the Civil War, and all the soldiers who were in Apache country have gone to kill each other."

Naiche said, "Let us wish them great success in such a worthy undertaking. Now is the time for Apaches to kill the white men who remain and again be masters in our own land."

"We are fast becoming masters," Geronimo said. "The three men I saw today must be either great fools or of great courage. Most white men dare not leave their cities of Tucson and Tubac unless they are in numbers and well armed. Their stages no longer run, and their mail carriers no longer ride. The ashes of their wagons are blowing throughout Apache land. Their houses and stage stations are abandoned to the sun and wind. Their graves are more than one man may count."

"True," Naiche agreed. "But I worry."

"For what reason?"

Naiche spoke thoughtfully. "First came the men who measured land and drove stakes in the ground. They left and we Apaches rested easier. Then came rock scratchers, gold seekers, to Pinos Altos, and again we had cause for anxiety.

"Thinking to be rid of the rock scratchers, Mangus Coloradus himself went among them and offered to lead them south to rich gold mines in the Sierra Madre. Truly the gold was there. And truly Mangus Coloradus would have led them to it, for at that time we had not yet learned the worth of gold. But the miners thought your Mimbreno chief was lying. They overpowered and bound him. Then they flogged him more mercilessly than we ever flogged the most rebellious Mexican prisoner.

"I worry because Mangus Coloradus is growing old," Naiche went on. "He cannot forget that white men fought us with weapons better than our own. When we won or stole such weapons for ourselves, they came with still better ones. Mangus Coloradus thinks that, when the white men are weary of killing each other, they will return with weapons even more terrible. He thinks the only hope for Apaches is to seek peace. Yet he fights on."

Geronimo said, "The only hope is to fight for that which is ours."

"I agree, but I worry for another reason," Naiche said. "My father, Cochise, long kept the peace. He let the white men run their stages. He protected their wagons and mail carriers from renegades who would have destroyed them.

"Then, only a few moons ago, a white chief named Bascom came to Apache Pass with some soldiers. He summoned Cochise to his tent, saying he wanted to talk. Suspecting no treachery, Cochise went with five warriors. Bascom said we Chiricahuas had stolen a boy named Mickey Free and some cattle. He demanded their return."

Geronimo said, "I have not heard all this story."

"Cochise denied that Chiricahuas had stolen either the boy or the cattle," Naiche went on. "Bascom gave him the lie and ordered his soldiers to make prisoners of those who had come to talk. Cochise escaped by slashing the tent with his knife and running. But the warriors were captured. So we captured some white men."

There was a moody silence while Naiche pondered his words. He continued:

"Meanwhile a white chief named Irwin, who outranked Bascom, came to Apache Pass. We sent word to him that we would free our white captives if our warriors were freed. Instead, while we watched from surrounding cliffs, Irwin had them killed in the peculiar fashion of white men. He tied ropes around their necks and let them dangle from a tree until they were dead. In turn, we killed our white prisoners."

"I was raiding in Mexico at the time, for I have raided Mexicans at every opportunity since the massacre at Kas-Kai-Ya," Geronimo said. "I wish that I had been present."

Naiche said, "If you had been, you would have seen for yourself why the Chiricahuas are at war with the white men. But, though no warrior is more courageous nor any chief more wise, I know my father. He wars with them now, but in his heart he, too, thinks that we must some day make peace with the white men."

"There is no peace at present," Geronimo said, "so let us return to the village, get guns, and kill the two white men I have just seen. We shall not find the third alive."

"Let us do that," Naiche agreed.

They rode into the Chiricahua encampment just in time to see the women and children, with an escort of warriors, leaving. The remaining warriors were looking to their weapons. Naiche and Geronimo made their way to Cochise, who was calmly giving orders to sub-chiefs.

"Why should this be?" Naiche inquired.

"Our scouts bring word that many soldiers from the land to the west, who call themselves the California Volunteers, are marching in this direction. They go to fight in the war that other white men are fighting to the east," Cochise said. "The path they have chosen will lead them through Apache Pass. I have sent word to Mangus Coloradus to join us. Then we will kill every soldier!"

At the exciting news of a great battle in store, Geronimo and Naiche forgot all about the two white men whom they had intended to find and kill.

High on the steep and boulder-strewn side of narrow Apache Pass, Geronimo lay behind a pile of rocks. He had made the little breastwork appear natural by uprooting a cactus and standing it on top of the rocks. His best rifle and all the powder and bullets he had been able to gather lay within easy reach. Now he had only to await the soldiers, who intended to march through Apache Pass, and to give thanks to Usan, who had created an ambush so perfect.

Apache Pass was a narrow slit between the Chiricahua Mountains on the west and the Dos Cabezas on the east. It was one of the very few passes in the Southwest through which travelers could take wagons. Far more important, in a land of little water it sheltered sweet and cool springs that never failed.

Turning his head, Geronimo saw the stone house built by men of the Overland Stage Company and abandoned since Cochise took the warpath. Some six hundred yards beyond the house, tall trees and green grass marked the flowing springs.

Geronimo smacked his lips in satisfaction.

Behind each rock in the pass, each shrub, each cluster of cactus, crouched an armed Apache. There were almost seven hundred Mimbrenos and Chiricahuas. They were so well hidden that even Geronimo, who knew they were there, could see few of them. He smacked his lips again.

The scouts had reported that there were about as many white soldiers as there were Apaches in ambush, some on foot and some mounted. The soldiers had stopped with their supply train at Dragoon Springs, forty miles west of Apache Pass. There they could drink to their heart's content, water their stock, and load up with enough water to see them through to Apache Pass. But their water would be gone by the time they entered the pass, and they could not get more until they reached the springs beyond the stone stagehouse.

Geronimo glanced with pleasure at the stone breastworks which Mangus Coloradus and Cochise had had built on the heights overlooking these springs. The fortifications were manned by warriors who could shoot without being shot, since the breastworks protected them.

Unable to renew their water supplies, the soldiers who were not killed by bullets would die from thirst. The greatest Apache victory of all time was almost certain.

Soon two Apache scouts who had gone out to watch for the soldiers' arrival came into the pass. One went to Cochise's ambush. The second turned to where Mangus Coloradus lay.

Geronimo burned to know what the scouts had seen and what they were saying, for then he would know how soon he might expect battle. But he did not leave his position.

Presently, Naiche slipped down beside Geronimo. He was grinning.

"Most of the heavy wagons, without which white soldiers go nowhere, remain at Dragoon Springs," he said. "A few horse and many foot soldiers are coming to Apache Pass, but they are no more than one to our six. They wear their foolish uniforms of blue cloth and they reel with the heat. They cannot live without water."

"Nor can they get water," Geronimo's grin reflected Naiche's. "Before they reach it we shall slay them all."

"We shall slay them all," Naiche agreed.

Naiche slipped back to his ambush. A half hour later Geronimo saw the thin cloud of dust that hovered above the marching soldiers.

The soldiers entered Apache Pass, and most of the cavalrymen led their mounts, for the horses were so desperate for water that they could not be ridden. There were pack animals too, and they carried strange wheels and tubes that were typical of the silly things white soldiers took into battle. But in spite of heat, thirst, and the heavy uniforms, the white men kept a smart military formation as they walked unsuspectingly into the trap.

They were two thirds of the way into the pass when a shot from the rifle of Cochise rang out. At once firearms blazed from behind the Indians' breastworks. But the hoped-for massacre did not come about.

This was partly because the Apaches were so sure the soldiers could not escape that they did not bother aiming as carefully as they should have. And it was partly because so many of the Indians were shooting smoothbore muskets that were not accurate at a long distance.

Even as he shot at them, Geronimo could not help admiring soldiers such as these white men. They did not flee in panic, as Mexicans nearly always did, but coolly shot back. In good order, shooting as they went and taking their wounded with them, they retreated from the pass.

Geronimo swallowed his disappointment. He had hoped all the soldiers might be slaughtered at the first volley. But he knew that those who still lived must reach the springs or die of thirst.

Leaving his position, Geronimo raced to the heights overlooking the springs. He found a place behind the breastworks on the heights and waited.

The white soldiers came again. But they were in battle formation this time, and their rifles were far superior to smoothbores. Every shot from an ambushed Indian drew a quick reply. Soldiers dropped, but here and there an Apache went limp too. Carrying their dead and such wounded as could not help themselves, the soldiers fought their way to the stone stagehouse. Some entered the building, and some sheltered themselves behind it.

Geronimo made ready for the attack on those who would attempt to get to the springs. He had thought not even one soldier would ever reach the stagehouse, but most were there. However, they were still six hundred yards from the water they must have and the deadliest ambush of all.

The soldiers stayed in or behind the stagehouse for almost an hour and a half. When they came out and advanced toward the springs, Geronimo was amazed to see them pulling little wagons with tubes mounted on them. Only warriors who knew nothing of battle would bother with such clumsy things. Geronimo's confidence rose.

The soldiers neared the springs, and the Apaches loosed a rain of bullets. Again, very few soldiers were hit.

It seemed to the puzzled Geronimo that the others were very busy with their little wagons. One wagon escaped from the men who were handling it and started to roll. Immediately other men pounced upon and halted it. They turned the little wagon about, so that the tube pointed at the breastworks.

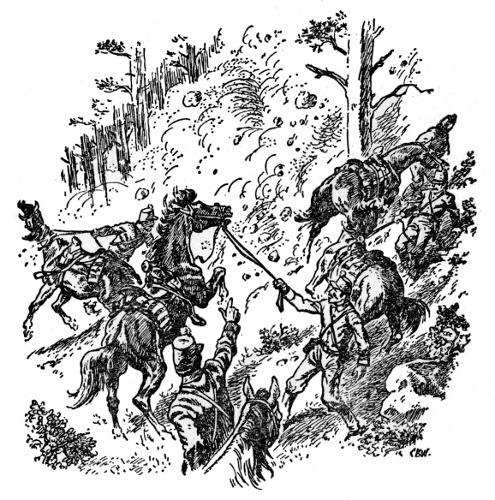

The first shell—for the little wagons were really howitzers—struck the breastworks squarely about thirty feet to one side of Geronimo. Dust, dirt, stones, boulders, and Apaches flew into the air.

The rest of the Apaches waited in stunned silence until the second shell exploded. Then the Indians began a panicky scramble up the slope.

When they reached the heights, Geronimo stood with Mangus Coloradus and twenty other Mimbreno braves and looked down on the battle ground. They watched the soldiers drink, fill canteens, and retreat with their horses to the stone stagehouse.

"We would have killed them all, but they shot wagons at us," Mangus Coloradus said wonderingly. "But we are still many more than they are, and we will kill them yet. To do so, we must first kill the messengers they will surely send for help. Come."

The warriors followed Mangus Coloradus to the west end of the pass. Soon they heard the pounding of horses' hoofs. A moment later they saw the five mounted messengers who were riding to warn those camped at Dragoon Springs of the ambush and to ask for help.

The Indians shot. Three horses went down at the first volley, but two riders were quickly pulled up behind two other soldiers and thundered on. There remained no one to help the rider of the third downed horse.

In the thickening night, the Apaches advanced to kill this lone man. The dismounted trooper crouched behind his dead horse and prepared to sell his life as dearly as possible.

The trooper's carbine cracked. Geronimo and two other warriors caught Mangus Coloradus as he fell and carried him behind an outjutting shoulder of rock.

They forgot all about the trooper who, after the Apaches left, made his way to his companions at the stagehouse and lived to tell the tale.

The sorrowful warriors gathered around their wounded chief. Grieving because he was hurt, they were also worried. While Mangus Coloradus led them, even though they might suffer temporary defeats, in the end they always triumphed. What now?

Nadeze said, "We need a medicine man."

"I am a medicine man," Geronimo said.

Geronimo told the truth. Following the massacre of Kas-Kai-Ya, he had taken the training which he needed in order to become an Apache medicine man. This he had done in the hope that he might discover some powerful medicine which would make sure the defeat of the rurales responsible for the massacre. But even though he had learned all the rituals that an Apache medicine man must know, he was far too intelligent to have much faith in them. But others believed in them.

He said again, "I am a medicine man."

"True," Nadeze agreed. "I had forgotten."

Opening his pouch of hoddentin, or sacred pollen, Geronimo rubbed a bit on Mangus Coloradus' forehead. Then he made a cross of hoddentin on the chief's breast. He sprinkled a thin line of the sacred pollen all around the Mimbreno leader and put a touch on the forehead of every warrior who stood near. Finally, he applied a pinch to his own forehead and took a bit in his mouth.

And even as he finished, he knew that hoddentin was not enough.

Geronimo was not so blinded by the ways of the Apaches that he was unable to see for himself that other people had better ways. Often he had seen rurales so badly wounded that he thought they could never fight again. Yet, in a later skirmish, he had fought the same rurales, and apparently they were as whole as before.

With the rest of the nearby Mimbreno braves too stricken to do anything, and no sub-chief near, Geronimo took charge.

He said, "Make a litter."

"Where do we go with my father?" asked Mangas, son of Mangus Coloradus.

"To the Mexican medicine man at Janos," Geronimo said.

Mangas said, "The Mexicans are enemies."

"That I know," Geronimo grunted.

He paid no more attention to Mangas. Though a brave warrior, the son of Mangus Coloradus lacked the qualities that made his father great. When he was forced to make an important decision, Mangas was never able to decide on the wise course and always trembled between the two.