| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/bypathsindixiefo00cockrich |

“DES LIKE SHE RUB’IN ON YORN.”

BYPATHS IN DIXIE

FOLK TALES OF THE SOUTH

BY

SARAH JOHNSON COCKE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

HARRY STILLWELL EDWARDS

NEW YORK

E·P·DUTTON & COMPANY

31 West Twenty-Third Street

Copyright, 1911

By E. P. Dutton & Company

Reprinted, May, 1912

TO MY HUSBAND

When Thomas Nelson Page began his stories of the old South in the early “Eighties,” the reading people of America suddenly aroused to the realization that a vein of virgin gold had been uncovered. There was a rush to the new field and almost every Southerner who had a story to tell told it, many of them with astonishing dramatic force and power. As by magic a new department was added to American literature and a score of new writers won their way to fame. From a notably backward section, in point of[Pg 8] expression, the South stepped easily, with the short story, into the front rank and has held her place ever since. The field once entered was explored faithfully, the eager minds of her sons and daughters running through the Ante-Bellum, Revolutionary and Colonial eras, and when Joel Chandler Harris developed the “Brer Rabbit” stories, “The Little Boy” and “Uncle Remus,” it seemed as though future work must lie in refining for the ore was all in sight.

But there was one lead almost entirely forgotten or undervalued in the scramble for literary wealth and this lead was into the Southern nursery where the real black Mammy reigned. With the better lights before us now we realize the astonishing fact that the very heart center of the Southern civilization had not been touched.

[Pg 9]Mrs. Cocke in the charming stories contained in this volume is the happy pre-emptor of the new find. Every Southerner old enough will recognize the absolute truthfulness of the scenes and methods therein embalmed, and applaud the faithfulness with which she has reproduced that difficult potency, the gentle, tender, playful, elusive, young-old, child-wise mind of the African nurse in the white family; the mind to which all things appeal as living forces and all lives as speaking intelligences.

The naturally developed mind of the African slave had no leaning to violence. The influence of the wildness of nature, the monotones of forests, fields and running waters, the play of shadows and the wind voices lingered in it and the tendency to endow all life surrounding it with human or[Pg 10] god-like powers as strong in an humbler way as with the early Greek. But the Greeks were warriors; the African slave tribes, never. Where one worshipped force, the other bowed to shrewdness and cunning and by these lived within a hostile environment. The rabbit that survives and multiplies was to the African slave always mightier than the lion that fell to the hunter’s gun or spear, and the rabbit was and, to a large degree still is, the best personification of the negro mind in its method of approach and treatment. Brer Rabbit in the stories retold by Harris is really the child-wise, world-old mind of Uncle Remus, himself a type. The absence from them of some of the moral laws is in itself one proof of faithful reproduction.

But in the nursery we had by necessity the[Pg 11] moral laws grafted on the African mind by master and mistress through daily association and the singular application of these is within the memory of many grown-up Southern children. I take issue with those who declare that the black Mammy did have equal authority in the punishment of refractory children. I have never known an instance in which punishment by her was inflicted in blows. A child might be dragged forcibly to its nursery, restrained by a turned key or remorselessly carried away to solitude, in arms, but struck, never! Blows were unnecessary with the wise-old Mammy. There were the cupboard and pantry, the fruit orchard, the kitchen stove, and there were the birds, beasts and fowls to be invoked in song and story. Thus were the children restrained, guided and taught, and doubtless[Pg 12] many a flower in our literary gardens to-day is but an old-time seed matured. This is the best side of the picture. The seed was not always well chosen; the impression, a good one. All black Mammies were not good and superstitions fertilized with fear were often sown in childish minds never to be eradicated. The writer to this day could not under any temptation bring himself to touch a spider or sleep in the dark and somehow feels that life will not be entirely complete without a chance to even up with the female Senegambian who filled his mind with weird stories Saturday nights and prepared him for religious service Sunday mornings.

Mrs. Cocke’s work speaks for itself. It is a difficult work presented with but few of the stage accessories. But I believe it is admirably done and will endure in a niche of[Pg 13] its own. Certain it is that those to whose memories it appeals will receive it gratefully.

Harry Stillwell Edwards.

Macon, Ga.,

April 10, 1911.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Rooster Telephone | 21 |

| II | Old Man Gully’s Hant | 37 |

| III | Jack O’Lantern and the Glow Worm | 57 |

| IV | Miss Race Hoss an’ de Fleas | 79 |

| V | Miss Race Hoss’s Party | 91 |

| VI | Ned Dog and Billy Goat | 107 |

| VII | How the Billy Goat Lost His Tail | 121 |

| VIII | Shoo Fly | 139 |

| IX | Election Day | 153 |

| X | Mister Bad ’Simmon Tree | 177 |

| XI | Big Eye Buzzard | 197 |

| XII | Miss Lilly Dove | 219 |

| XIII | Mister Grab-all Spider | 243 |

| XIV | Mister Rattlesnake | 261 |

| XV | Miss Queen Bee | 281 |

| XVI | Mister Tall Pine’s Christmas Tree | 301 |

| XVII | An Afterword | 319 |

(From drawings by Duncan Smith.)

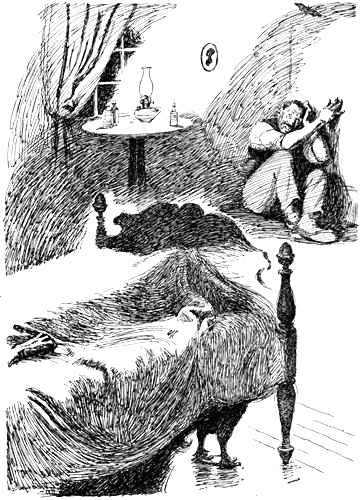

| “Des like she rub’in on yorn” | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| “Dat ole roost’r squattin’ und’r de baid ain’ nuv’r tak’n his eyes off’n Abe” | 50 |

| “Hep! Hep!—Somebody come hope me!” | 60 |

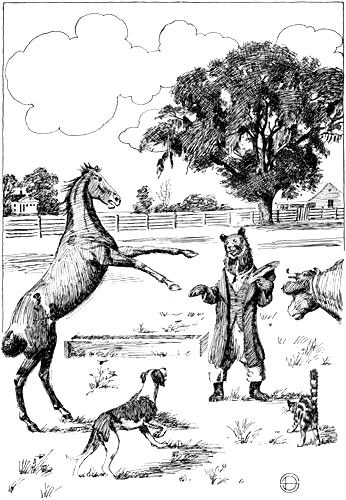

| “Wid dat dey all uv ’em lose dey manners an’ start ter ’busin’ Brer Bar scand’lous” | 102 |

| “Shoo Fly holl’r, ‘Look out fur m’ legs!’” | 148 |

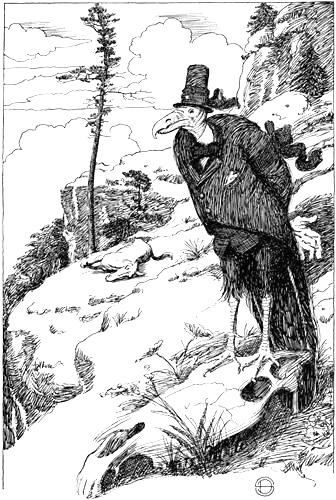

| “Bimeby he git ax’d ter be er pawl b’arer ter all uv ’em” | 206 |

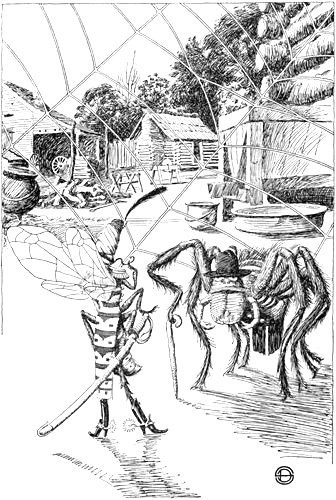

| “Mist’r Grab-All, ’cose you gwine jine de Yall’r Jackits’ side, ain’t yer?” | 244 |

BYPATHS IN DIXIE

The telephone had just been mended again, and the man suggested as he left that the little boy find another plaything. Phyllis indignantly protested that Willis had done no damage to the instrument, and that the frequent defects were due to the failure of the workman to put it in proper condition. Being thus defended by so strong an ally, Willis lost no time in attacking the forbidden object as soon as the door was closed.

“Let de ole telerfome erlone, baby,” said[Pg 22] Phyllis in a tone of sympathetic protest. But the boy could not resist such an opportunity. “Dat table tiltin’ right now.” She caught her breath as the table righted itself. “An’ dat telerfom’ll bus’ yo’ haid wide op’n.”

“I’m going to talk to my papa.”

“You gwinter talk ter er bust’d haid, dat’s who you—” At that moment, table, telephone, boy and all fell to the floor with a bang. “What’d I tell yer?”

Willis answered with a succession of screams that admitted of no argument or consolation. Phyllis offered none until she had satisfied herself that a bumped head and a much frightened little boy were the extent of the damage.

“Mammy gwine whup dat telerfome,” she continued, “an’ de flo’ too, caze dey hu’t her[Pg 23] baby.” And she proceeded to execute the threat.

“Don’t whip the telephone—whip the table!” he screamed.

“Dat’s right,” striking the table with a towel; “’twas dat ole table done all de mischuf—Mammy gwina rub camfer on dat telerfome’s haid des like she rub’in on yorn, an’ beg his pard’n too,” looking for the raised place. “Come on ov’r ter de wind’r so Mammy kin see her baby’s haid good!”

“I don’t want you to see it good!” And the wails redoubled.

“Lawsee! Look at dat ole rooster in de yard!” half dragging the little fellow to the window; “he’s done gone an’ telerfome ter Miss Churchill’s rooster ’bout you holl’rin’ an’ kicken’ up so!”

“No, he shan’t!” blubbered Willis.

[Pg 24]“He done done it, an’ he fixin’ ter do hit ergin!”

Another crow from the rooster: “I tole yer so! heah ’im? An’ Miss Churchill’s rooster done telerfome ov’r ter Miss Coxe’s roost’r, an’ dey keeps on telerfomin’ ter de nex’ yard tell all de roost’rs in dis whole place’ll know you settin’ up hyah cryin’ an’ yellin’ like you wus Ma’y Van.”

“I don’t want ’em to tell,” said the little boy, burying his face on her shoulder.

“I doan speck yer does, but he done tole hit!” A fresh burst followed, which Phyllis strove to quiet. “Hyah, eat dis nice butt’r’d biskit Mammy bin savin’ fur yer.” Willis pushed the bread away. She coaxed, “I speck ef you eats er lit’le, an’ thows er lit’le out yond’r ter ole man Roost’r, he’ll git in er good humor (like all de men fokes does[Pg 25] whin dey eats), an’ he’ll telerfome ter Miss Churchill’s roost’r dat he jes foolin’ him, an’ Miss Churchill’s roost’r’ll keep de wurd passin’ erlong dat way tell all de roost’rs’ll know our ole Shanghi jes pass er joke off on you.”

“Where’s his telephone?” sniffled the boy, only partly diverted by the chicken pecking up the crumbs of bread.

“He keep hit in his th’oat whar de Lawd put hit.”

“How can he eat?” Willis turned from the window to gaze into the old woman’s face.

“Pshaw, boy, you think er stool an’ er table wid er telerfome on hit’s in dat roost’r’s th’oat?” and she laughed aloud. Moistening the handkerchief again with camphor, she parted the curls and tenderly pressed the[Pg 26] cloth to the bumped place. “Nor suhree! dey ain’ no sich er thing in dat roost’r’s th’oat. Mist’r Man put dat un in hyar fur yo’ ma,” pointing in the direction of the ’phone, “but de Lawd hook up dat un out yond’r in ole man Roost’r’s th’oat. Yas, Lawd! He put hit in dar fur Roost’rs ter talk wid an’ fur fokes ter lis’n ter whut dey talks. You ’member de uth’r night when you wus took sick in de night, an’ Mammy keep er tellin’ yer ter stop cryin’ ’bout de cast’r oil, an’ lis’n ter de roost’rs crowin’? Well, our ole roost’r wus jes gittin’ news fum Peter’s roost’r den.”

“Who’s Peter?” Willis shook the camphor cloth from his head. “Who’s Peter, Mammy?” he insisted.

“Lemme see how I kin ’splain ter yer who Peter is,” scratching her head under the[Pg 27] bandana. “Lemme see—Peter wus er gent’mun de scriptur speak erbout dat trip hissef up on de ‘Bridge er Trufe’ an’ fell er sprawlin’ flat; an’ de Lawd sont er roost’r ’long ’bout dat time ter pick ’im up. Cose you know de roost’r didn’t pick ’im up wid his foots, but he raise him up wid er speeret de Lawd put in ’im fur dat ’speshul ’casion. Oh, I tell yer, de Lawd talks er heap er talk ter fokes thu fowels an’ beastes, but nobody doan take no notice uv ’em; dey ’pears ter fergit how dat fowel hope Peter up, an’ pint’d de road ter Glory fer ’im.”

“Mammy, can roosters talk show nuf?”

“Roosters kin talk good es you kin,—hits jes fokes ain’ got nuf speeret in ’em ter heah whut dey says. Way back yonder time whin hants an’ bible fokes projeck’ wid one nuth’r, beastes an’ speerets confabs wid[Pg 28] fokes, jes like me an’ you talkin’ now! Yas, suh, an’ fokes lis’ns ter de confab dem sorter creeters talks too! Whar you speck ole man Balim wud er bin terday ef hit hadn’t er bin fur dat mule er his’n? But screech owels an’ jay birds an’ er heap mo’ ’sides chicken roosters is got speerets in ’em in dese days too. Some fokes calls ’em hants!”

The door opened and little Mary Van, who had caught the last word, tripped quickly to the old woman’s side and whispered in suppressed excitement: “Where’s the hants, Mammy Phyllis?”

“Nem’ine whar de hants is terday. I’m talkin’ ’bout de rooster telerfome. Yer see Peter’s rooster’s settin’ up in rooster heb’n keepin’ his eye out fur all de news. He nuv’r do go ter sleep reg’lar; sometime at[Pg 29] night he sorter nod er lit’le, but he nuv’r do git in bed, caze he feer’d Mist’r Sun wake up ’fo’ he do. Well, whin he heah ole man Sun gap loud, an’ turn hisself ov’r an’ scratch, he know he fixin’ ter git up, an’ dat minit he flap his wings an’ telerfome loud es he kin ‘de break er day is c-o-m-i-n’’ (imitating the rooster). Ole man Diminicker down yonder on yo’ gran’pa’s rice plantation, down on de aige er de oshun, is de fus ter git de news. He stir hissef erbout an’ flop his wings, an’ telerfome loud es he kin, ‘de break er day is c-o-m-i-n’.’ De rooster on de nex’ plantation gits de wurd an’ dey passes hit on tell our ole rooster gits hit way up hyah in de mountains. Den our ole Shanghi keeps de wurd er gwine, tell ev’ry chickin fum one side de country ter de uth’r knows day fixin’ ter break.”

[Pg 30]“Mammy, Mister Rooster wants some more biscuit.”

“I ’speck he do; did yer ev’r know er man dat wus satisfied wid what wus give him? Yas, Lawd! dat rooster’ll stan’ dar an’ peck vit’als long es you thows hit ter ’im, eb’n whin he feel hissef bustin’ wide op’n; he’ll stretch his neck ter git one mo’ bite whilst he’s dyin’.”

“Who’s dyin?”

“Nobody ain’t dyin’, caze dat rooster ain’ gwina git ernuf fum me an’ you ter do him no harm.”

“Make him telephone again.”

“Nor, he say he want ter pass er lit’le conversation wid Sis Hen, an’ Miss Pullet, an’ tell ’em, mebbe ef dey scratch hard ernuf, dey’ll fine some crum’s er his but’r’d biskit.”

[Pg 31]“Why didn’t Mister Rooster save ’em some?”

“Who, dat rooster?” Phyllis shook her head. “Dem wimmen hens doan git nuthin’ but whut dey scratches fur,” then thoughtfully she added: “Cose all roosters ain’ ’zackly erlike. Dey’s er few, but recoleck I says er pow’ful few, dat saves mos’ ev’ything fur de hens an’ chickens; den der’s some uv ’em dat saves right smart fur ’em; den der’s er heap uv ’em dat leaves ’em de crum’s, but de res’ er de rooster men fokes doan leave ’em nuthin’, an’ de po’ things hatt’r scratch fur der sefs.”

“Less give Sis Hen and Miss Pullet some biscuit too,” Mary Van insisted.

“You think Willis’s pa got ter feed all de po’ scratchin’ hens in dis worl’?—well, he ain’t.”

[Pg 32]“Give ’em this piece. It hasn’t got any butter on it.” Willis handed her the bread.

“Lawsee,” she threw up the disengaged hand and brought it down softly on the little boy’s head, “but ain’t you ’zackly like all de uth’r roosters—an’ hens too fur dat matt’r—willin’ ter give ’em dat ole crus’ atter you done eat all de sof but’r’d insides out’n it!”

A lusty crow sounded from the rooster in the yard.

“Mammy, what did Mister Rooster say?”

“He say ‘dey’s er good little boy in h-y-a-h,’” trilled Phyllis, imitating the rooster’s crow.

Willis smiled while his hands unconsciously clapped applause. Slipping from her lap, he ran about the room flapping his arms and crowing: “There’s a good little[Pg 33] boy in h-e-r-e, there’s er good little boy in h-e-r-e.”

Mary Van started in the opposite direction: “There’s a good little girl in h-e-r-e.”

“Hush, Mary Van,” commanded Willis; “you can’t crow, you’ve got to cackle.”

“I haven’t neether; I can crow just as good as you. Can’t I, Mammy Phyllis?”

“Well,” solemnly answered Phyllis, “it soun’ mo’ ladylike ter heah er hen cackle dan ter crow, but dem wimmen hens whut wants ter heah dersefs crow is got de right ter do it,” shaking her head in resignation but disapproval, “but I allus notice dat de roosters keeps mo’ comp’ny wid hens whut cackles, dan dem whut crows. G’long now an’ cackle like er nice lit’le hen.”

[Pg 37]“Put some bread crumbs on top of the barrel, Willis, and less see if he can peck it off,” suggested Mary Van in baby treble.

The Langshan seemed to understand, for he watched Willis with interest as he crumbled the bread; and after due consideration, and with an almost human scorn towards the hens, measured his steps to the barrel, and stretching his long neck, removed every crumb from the top. After this he slowly raised one foot as though to return to the company of hens, but changing his mind, stood with the foot poised in air and one eye apparently fixed upon Phyllis.

[Pg 38]“Come on, chillun, I ain’ gwine stay hyah an’ let dat ole chicken conjur me.”

“I don’t want to go, Mammy, I want to stay and feed the chickens,” protested Willis.

“I want to see him eat off the barrel some more,” pleaded Mary Van.

“Dat rooster ain’t no chicken, I tell yer, ’tain’ nuthin’ in dis worl’ but er hant.”

This closed the argument, for they felt the mysterious influence of “hants” that was upon Phyllis, hence they followed like the meekest of lambs until she stopped at her own room in the yard. After stirring some embers to a flickering sort of blaze, she looked insinuatingly about her and broke into an excited whisper: “Whinsomev’r yer sees enything right shiny black, widout er single white speck on hit nowhar, you[Pg 39] kin jes put hit down in yo’ mine, dats er hant! ’Tain’ no use ter argufy erbout it; dem’s de creeturs dat speerets rides whin dey comes back ter dis worl’. An’ ’twas one er dem same black, biggity Langshans dat ole man Gully’s hant come back inter.” Phyllis had taken her seat by this time, and the children had scrambled into her lap. “Sakes erlive! You all mos’ claw me ter death. How yer ’speck erbody ter be hol’in’ two growd up fokes like youall is?” But the children continued to climb, one on each knee. Phyllis put out her foot and dragged a chair in front of her. “Hyah stretch yer foots out on de cheer, an’ mebby ef yer sets still, I kin make out ter hole yer.”

“Mammy, where do hants stay?” asked Willis.

“Hants is ev’r whars,” she looked about[Pg 40] her; “dis hyah room right full uv ’em now.”

Mary Van’s head was immediately buried on the old woman’s shoulder, while Willis’s arms locked tightly around her neck.

“Yas,” she continued, in low mysterious tones, “dis whole wurl’s pack’d full uv ’em, but ’tain’ no use ter git skeer’d, long es dey ain’ got no bisnes’ wid you. De time ter git skeer’d is whin you sees ’em!” (A scream from Mary Van answered by a tremor from Willis.) “Some fokes doan git skeer’d den, kaze dey knows ’tain’ no use ter git skeer’d er good speerets—hit’s jes dese bad hants dat does de damage.”

“Tell us about a good, good spirit, Mammy,” came in muffled tones from Mary Van.

“Cause we don’t want to hear about bad old hants,” finished Willis.

[Pg 41]“How yer speck me ter tell yer enything wid you chokin’ me, an’ Ma’y Van standin’ on her haid on m’ should’r. Set up like fokes—you hole dis han’ an’ let Ma’y Van hole dis un, an’ I’ll tell yer ’bout old man Gully’s hant.”

“Ole man Gully wus de biggites’ creetur’ you ev’r seed; he jes nachilly so biggity he ’fuse ter do er lick er wurk. Plantin’ time er harves’ time ain’ make no diffunce ter ole man Gully. He set up on his front po’ch an’ smoke his pipe, an’ read de newspaper an’ eat same es one dese ole buckshire hogs, whilst his old lady, an’ de chilluns, an’ der ole nigg’r Abe, done all de wurk.

“Ole Miss Gully wus pow’ful sot on de ole man; she think he’s de mos’ pow’fules’ gran’ man in de wurl. Ef he say ‘I wants er chaw er ’bark’r,’ de ole lady’d break her[Pg 42] neck runnin’ ter de fiel’ ter tell Abe ter take de mule out’n de plow an’ fly ter town fur de ’bark’r. Den she’d git de old broke down steer an’ go ter plowin’ tell Abe come back. All dis time ole man Gully snoozin’ on de po’ch in de cool. Ef er rainy spell come an’ spile de wheat, er ef fros’ come an’ kill de fruit, ole man Gully ’buse de ole lady an’ de chilluns, an’ say ef dey had er done like he tole ’em hit nuv’r wud er hap’n’d.

“One day long ’bout de mid’le er de sum’r, Mist’r Gully say he bleeg ter have some possum vit’als. Cose nobody doan eat no possum dat time de ye’r, an’ ’taint’ no time ter hunt ’em nuthe’r, but ole man Gully says, ‘I wants de possum,’ an’ dat wus ’nuf fur de Gullys. Abe an’ de chillun stops all de wurk on de farm an’ go possum huntin’. Dey hunts all day, an’ dey hunts all night[Pg 43] ’fo’ dey so much es come ’crost er single possum track. Bimeby, att’r day had mos’ give out, hyah come er big lean, lank ole possum up er ’simmon tree full er green ’simmons. Dey runs home quick an’ giv’ hit ter dey ma, an’ Lawsee! by de time dat possum an’ tat’rs ’gun ter cookin’ up good, de smell uv hit jes nachally make Abe an’ dem chilluns mouf dribble tell dey can’ do er lick er wurk fur standin’ ’roun’ de kitchen smellin’ dat possum. Miss Gully had er plenty er fat meat an’ sop fur de chillun, but dat big deesh er possum an’ tat’rs at de haid er de table done steal all der appertite, an’ dey wus settin’ dar turnin’ ov’r in der mines which one gwine git de bigges’ piece.

“Pres’ntly Mist’r Gully sorter cla’r his thoat an’ push his plate erway an’ pull de deesh closter ter ’im an’ cas’ er eye ’roun’[Pg 44] de table sorter mad like, an’, honey, dem chillun know right den an’ dar dat dey got ter eat fat meat an’ sop fur sup’r, er dee doan git no sup’r. De bigges’ boy sorter wipe his eyes er lit’le, an’ de nex’ two chillun, dey out an’ sniffle. De ole lady twis’ her mouf like she tryin’ ter say ‘doan spile yo’ pa’s sup’r.’ An’ de ole man make out he ain’ heah nuthin’ nur see nuthin’. Pres’ntly he look up wid his mouf right full er tat’rs an’ possum an’ see de chillun’s eyes feas’in’ on ’im, an’ der moufs wurkin’ like his’n, an’ he feel sorter ’shame. He swaller hard he do, like he’s fixin’ ter give ’em some, den he change his mine an’ say, ‘G’long in de yard, chillun,—Pappy’s sick, let Pappy eat de possum.’”

“Make Mister Gully give them some, Mammy,” said Willis indignantly.

[Pg 45]“He hatt’r go back like Niggerdemus an’ be born’d ergin ef he do. Nor suhree, he eat up ev’y speck er dat possum, an’ he sop up ev’y drap er dat gravy too; den he stretch hissef an’ say he ’speck he’ll g’long ter bed an’ try ter git er good night’s res’. Den all de fambly hatt’r g’long ter baid too, so de old man kin git ter sleep. Bimeby, long’ ’bout time de moon sot, hyah come sump’in’ nuth’r knockin’—knockin’—knockin’, on de wind’r blines.

“‘Who dat?’ sez ole lady Gully.

“Sumpin’ nuth’r keep er knockin’ an’ er knockin’. Bimeby de old dog ’gun ter howlin’, an’ de chickens ’gun ter crowin’, an’ de pigs ’gun ter squealin’, an’ de kitchin do’ blow’d wide op’n, an’ de sumpin’ nuth’r come tippitty, tippitty, tip, ’long up de hall.

[Pg 46]“‘Who dat?’ sez ole lady Gully ergin.

“De sump’in’ nuth’r keep er comin’ tippitty, tippitty, tip, right ’crost de ole lady’s foots on de baid. She holl’r an’ squall fur de ole man an’ de chillun’ ter come kill hit. De chillun an’ Abe come er runnin’ but de ole man ain’ stirry er speck.

“‘Lawsee mussy! Light de candle quick,’ sez she.

“An’ whut ’twus you ’speck dem chillun foun’?”

“What, Mammy?” came in a chorus.

“Er big ole Langshan rooster, jes like dat varmint out yond’r. Yas suh, dar hit sot on de foot er de baid, quoilin’ an’ grumblin’ like fokes. De ole lady tell Abe ter run Langshan out ’fo’ he wake up de ole man, but Lawd er mussy! Abe ’gun ter howlin’: ‘Oh! my Lawd, Marst’rs daid! Marst’rs[Pg 47] daid! an’ dis hyahs his hant!’ Sho’ nuff de ole man wus layin’ dar stiff an’ stark daid!”

“Is Papa’s rooster old man Gully, Mammy?” whispered Willis.

“Hit mout not be dis same ole man Gully, son, but hit’s some ole man Gully, sho’ es you born. Well, de ole lady she ’gun ter moanin’ an’ takin’ on tur’bl’, she did, an’ de Langshan he settin’ up cluckin’ an’ quoilin’ tell nobody can’ heah der own ye’rs. Dey darsn’t ter drive ’im out—nor suh, eb’n de und’r tak’r skeerd ter do dat, so ’tain’t long ’fo’ dat ole Langshan chick’n boss ev’ythin’ on de farm. Yas suh, I tell yer, Abe an’ dat ole ’oman act scand’lous ter dat chickin. De ole lady, she love hit, but Abe, he jes nachelly skeer’d er de hant. Dey nuv’r raise sich er crap b’fo’, ’caze dat rooster scratchin’ all ov’r de fiel’, an’ Abe[Pg 48] say he know whut you doin’ wheth’r he lookin’ at yer er not.

“Ev’y time Langshan ’ud speak sof’ ter de hens, Miss Gully’d holl’r ter Abe, ‘Yer marst’r want some fresh wat’r, run quick,’ Whinsomev’r Langshan’d crow, she run an’ git him mo’ vit’als. Oh, I tell yer dem dominicker hens whut kep’ comp’ny wid him sholy got fat an’ lazy eatin’ all day an’ doin’ nuthin’ but cacklin’ conversation wid him. An’ dey’s er heap er fokes in dis town too, dat doan do no mo’ dan dem hens does.”

“Did the children call Langshan papa?” interrupted Willis.

“Nor, darlin’, dem boys doan b’leef in hants, an’ dey tell dey ma dat de rooster jes foolin’ her, but she crack ’em crost de haid wid de broom stick, an’ dey darsn’t say so no mo’.

[Pg 49]“Long ’bout Chris’mus time Miss Gully wus took down wid de rumatiz. She can’t lif’ er finger, let lone git up, so she tell Abe ter bring de ole man up in de house. Yas suh, dat rooster strut hissef all ov’r dat house. He peck at hissef in de lookin’ glass, an’ he light up on de pianny in de parler; he fly up on de baid an’ peck Miss Gully’s nose, an’ she tell Abe de ole Man’s lovin’ her. Hit sho’ wus cur’us ’bout dat rooster, caze ev’y time de doct’r come, he hop up on de foot er de baid an’ cluck, an’ cluck tell de doct’r git up an’ go. One day de doct’r tell Miss Gully she gwine die. She sorter cry ’bout hit er spell, den she sont fur de ole man’s hant. Abe he go an’ shoo de roost’r in de room, but he can’t make him fly on de baid. Abe he tiptoe an’ wave his han’s sof’ like b’hime him, but de rooster[Pg 50] run und’r de baid an’ cackle, an’ cluck, an’ make so much fuss dat de boys wanter run him out, but Miss Gully say he talkin’ ter her. She answer back ter him, ‘Yas, suh,—dat’s right,—yas, suh, I’m gwine do jes like you says.’ She keep er gwine on dat erway er long time, tell bimeby she tell Abe ter go git lawyer Clark ter make her er will. She say de ole man say she got ter give him all de money, dat de chillun’ll spen’ hit ef she don’t. De lawyer argufy wid her ’bout doin’ sich er trick es dat, but he thowin’ ’way his bref, caze by de time he git thu’ wid dat speech, Miss Gully wus done daid.”

The children took a long breath. “Did the hant kill her, Mammy?”

“Hit conjur her so she dunno whut she doin’, jes like dat ole chickin try ter do me.”

“DAT OLE ROOST’R SQUATTIN’ UND’R DE BAID

AIN’ NUV’R TAK’N HIS EYES OFF’N ABE.”

[Pg 51]“Did the children cry when their mama died?” came tremulously from Mary Van.

“Dey car’ied on right sharply, caze she wus er good ole ’ooman ’fo’ she got conjured, an’ she wus jes doin’ what she think wus right den; but der cryin’ wusn’t nuthin’ ter dat nigg’r Abe howlin’ an’ moanin’ ov’r in de cornd’r. Yer see dat ole roost’r squattin’ und’r de baid ain’ nuv’r tak’n his eyes off’n Abe, an’ Abe want ’im ter g’long an’ keep comp’ny wid somebody else sides him. So he holler’, ‘Mistis, fur de Lawd’s sake make Marst’r g’long wid yer.’ Den de ole rooster start ter cluckin’ an’ fussin’, an’ hit ’pear dat he fixin’ ter go to’ards Abe. Abe he start ter hol’rin’: ‘Nor suh, nor suh, I doan want yer ter g’way fum hyah! I wants Mistis ter come back in one dese big Langshan hens, so you won’t git so lonesome,[Pg 52] dat’s whut I wants.’ De rooster keep on er cacklin’ an’ er fixin’ ter fly out’n de wind’r, but Abe think he gwine jump on him, an’ he yell, ‘Please suh, doan hu’t Abe, Marster, caze whin I dies, I’m gwine come back in one dese fine gooses, an’ wait on yer plum tell jedgement.’”

“Did old Langshan get all the money, Mammy?” the financial side appealing to Willis.

“He git much uv hit es hit take ter buy pizen ter make er conjur pill ter kill him wid.”

“Can you kill a hant?” he asked incredulously.

“Yer can’t kill ’em ’zackly, but yer kin run ’em inter sum uth’r creet’r, dat is ef de conjur pill wurk.”

“Mammy,” began both children at once.

[Pg 53]“Hole on,—jes one ax at er time—let de lady have de fus time, caze you’se Mammy’s man. Now den, ax yer sayso, Ma’y Van.”

“Did Miss Gully turn to a hen?”

“She done bin eat up long ergo ef she did,” then turning to Willis, “Whut’s Mammy’s man got ter ax?”

“I want to know how Abe turned to a goose.”

“Abe didn’t hatt’r turn ter no goose ertall, caze de Lawd done alreddy born’d him er goose.—Come on now, an’ less play in de yard.”

[Pg 57]“Mammy, you cut m’ Jack-my-Lantern for me.” Willis was struggling to carve features in a huge pumpkin.

“I tole yer ter let Zeek make dat foolish lookin’ thing,” grumbled Phyllis, faithfully striving however to cut the pumpkin according to Willis’s instructions.

“Make Mary Van one too,” he demanded.

“I got one,” and Mary Van blew into the kitchen door with a gust of chilly wind, “and Papa’s made a pretty one for you too, Willis—ain’t you glad?”

“Whut you all think dem Jacky-Lanterns[Pg 58] is enyhow?” Phyllis asked with an air of mystery.

“They are—” Willis hesitated, “they are—funny pretties,” he finished.

“Dey ain’ nuthin’ funny ’bout er show nuff Jack-my-Lantern, I kin tell yer dat fur sartin an’ sho!” Her face assumed a grave expression, “and—take keer, boy, Kitty’ll spill hot greese on yer,” making a dive at Willis in time to save the cook from stumbling. “Come on out er dis hyah kitchen,—’tain’ no place fur chillun no how.”

“Mammy, less go over to Mary Van’s and get m’ Jack-my-Lantern,” coaxed Willis, as Phyllis directed the way toward the nursery.

“Nor, yer doan need hit tell dark. Jack-my-Lanterns doan come out ’cep’in’ at night. Leastways fokes doan see em.”

“Jack-my-Lanterns ain’t anything but big[Pg 59] old pumpkins, are they, Mammy Phyllis?” Mary Van asked to reassure herself.

“Dat dey is,” the old nurse’s expression grew fearful and cunning. “Dey’s de wuss sorter hants—dat’s whut dey is.”

This ended the contention of going to Mary Van’s.

“You memb’rs,” she began after an ominous silence, “ole man Gully’s hant, doan yer?”

“Old Langshan rooster, Mammy?” Willis whispered.

“Dat’s de ve’y hant—yas suh—ole lady Gully ain’t skeercely in her grave ’fo’ dat rooster hant start ter gwine down in de cellar—an’ peckin’ ’roun’ like he huntin’ fur sumthin’.

“Abe tell de boys he seen de ole man take er bag er gole down dar onct, an’ he ’speck[Pg 60] old Langshan know whar he berry hit—but howsumev’r dat is—one thing wus sho’—dat rooster peck in one cornder er dat celler, tell dem boys pis’n him.”

The children moved closer to Phyllis. “Mammy, did he come back in another rooster?”

“No, ma’m, he didn’t,—he say he nuv’r speck ter come back in no mo’ creeturs ter git pis’n’d ergin. ‘De nex’ time I comes back,’ sez he, ‘hit’s gwine be in sumthin’ nuth’r fokes can’t projick none er der dev’ment wid.’ Ahah,—an’ yer knows whut dat is, doan yer?”

Both little heads shook a trembling negative.

“Well, hit’s er Jack-my-lantern!” said Phyllis, and at her solemn statement the children looked aghast.

“HEP! HEP!—SOMEBODY COME HOPE ME!”

[Pg 61]“Yas, ma’m,—an yas, suh,” she bowed to each in turn, “he come back straight es he kin float hissef ter de swamp down yond’r on yo’ granpa’s rice plantation.” She waited for this to be entirely absorbed by her eager little listeners, then added: “I seen ’em m’sef winkin’, an’ blinkin’ all erbout dar,” suiting facial contortions to her words.

“One day Miss Gully’s bigges’ boy went down in de cell’r ter git some tat’rs fur dinn’r, an’ fus’ thing yer know he start ter yellin’ ‘Hep! hep!—Somebody come hope me!’

“Abe an’ de uth’r boys wint down dar, an’ seed de boy layin’ flat on de floo’ whar de hant thow’d him—”

“Mammy, lemme get in your lap,” begged Mary Van, while Willis jumped on one of[Pg 62] her knees. Mary Van followed suit, and before Phyllis could reply they had cuddled upon her, almost taking her breath.

“Sakes erlive! you all gittin’ ’way wid me wusser’n dem hants done de Gully boys.”

“Go on, Mammy,” they both urged.

“Well, Abe an’ de uth’r two boys fotch him up sta’rs an’ lay him on his ma’s baid. Dey lef’ him er minute ter go git some cam’fer, an’ when dey come back, dar sot er crow on de haid er de baid tellin’ de boy:

“‘Go foll’r de light,

Don’ feer ter fight,

An’ yer’ll git er bag er gole!’

“He git up, he do, an’ go out de do’, but hit’s s’ dark he tell de crow he can’t see how ter git erlong. Jes den Jacky-Lantern flash up an’ say:

[Pg 63]

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“De boy run up ter de light, but hit go out jes es he git clost up ter hit. He say: ‘Hole on dar, whar yer takin’ me?’ Jacky-Lantern say

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“Johnny Squinch Owel fly b’fo’ him an’ say:

“‘Unch-oo, unch-oo,

Doanchu go, doanchu go!’

“Boy tell him, ‘Git out’n m’ way, Johnny, I’m atter money—I ain’ got no time ter talk ter you.’

“Johnny, he keep er foll’rin’ de boy an’ holl’r:

“‘Unch-oo, unch-oo,

Doanchu go, doanchu go.’

[Pg 64]“Jacky-Lantern light up ergin, an’ de boy start up runnin’. ‘I’ll git yer dis time,’ he say; but Jacky-Lantern drap down in de groun’ ev’y time he git enywhars near ’bouts him, an’ Willie Wisp pop up way ov’r de uth’r side.”

“Who was Willie Wisp, Mammy?”

“He wus er nuth’r hant dat tak’n up wid ole man Gully. When de boy see Jacky-Lantern pop up hyah, an’ Willie Wisp pop up dar,—he jump fus’ dis erway, an’ dat erway tell—”

“What was the boy’s name?” asked Willis.

“Lemme see, I b’leef dat boy name Jack.”

“No, Mammy, Jacky-Lantern’s name, Jack,” Willis reminded her.

“Dat’s so.” She dropped her head on one side: “Dat Gully boy’s name, Bill—Bill Gully’s his name. Dem uth’r two boys an’[Pg 65] Abe takes atter Bill an’ holl’r ter him ter let dem hants erlone, but Bill tell ’em ter ’ten’ ter der own biznes, dat he atter gole.

“Dey holl’r back, ‘Dey’s er plenty er gole in de cell’r—come on back an’ hope dig hit out.’

“‘I doan want no lit’le gole you fines at home,’ sez Bill.

“Abe he holl’r back ergin, ‘Please, suh, come back, dar’s er heap mo’ hyah dan you kin git dar.’

“But he so tie’d runnin’ fus’ atter Jacky-Lantern, an’ den atter Willie Wisp, dat he hatt’r stop an’ blow er lit’le. Abe an’ de boys dey kotch up wid him, an’ dey tussels consid’rble tryin’ ter git him back, but dat boy Bill skuffle scand’lus. He thow ev’y one uv ’em flat in de mud.

“‘You all ain’ nuthin’ but er passel er[Pg 66] gooses,’ he say, ‘talkin’ ’bout huntin’ gole at home. Don’t yer know yer got ter fight an’ scratch, an’ run, an’ keep er gwine tell yer gits ter whar dese hyah gol’ lights lives—den yer fines de bag er gole?’

“Fo’ de boys an’ Abe kin git dersefs up of’n de groun’ whar Bill knock ’em, Bill wus gwine like er race hoss atter Jacky-Lantern. Bimeby de groun’ ’gun ter git pow’ful sof’, an’ Bill, his foots ’gun ter sink down tur’bul. He can’t go fas’ no mo’,—I tell yer de trufe, hit wus all Bill cud do ter pull hisse’f erlong.”

“What was the matter with Bill, Mammy Phyllis?” whispered Mary Van.

“He in de swamp, honey, whar de groun’ wus mirey,—an’ hit wus full er hants too. Bill feel er hot flash pass him, an’ er Jacky-Lantern’d pop up—hyah come ernuth’r hot[Pg 67] sumthin nuth’r, an’ Willie Wisp ’u’d pop up right ’long side er him.

“Bill say, ‘Is dis whar yer lives?’

“Jacky say:

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“Johnny Squinch hoot up in de tree: ‘Unch-oo, Doanchu go.’

“Brer Bull Frog holl’r: ‘Go back, go back.’

“Ole lady Gully’s hant come up in er big ball er light, an’ she moan ter Bill:

“‘Foll’r yer track,

Ef yer wanter git back.’

“Bill say: ‘Who is you?’

“Miss Gully say:

“‘I’m yo’ Mar—

Doan go so far.’

[Pg 68]“Bill say, ‘I done start atter dis gole, an’ I’m gwine see de race out.’

“Jacky-Lantern an’ Willie Wisp, an’ all de res’ er de bad hants down in de swamp jes er poppin’ up ev’y which er way, an’ all uv ’em holl’r:

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money!’

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“Bill he dunno which way ter go, so he ax ’em: ‘Which one got de money sho nuf?’ But dey keeps er bobbin’ up:

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

[Pg 69]tell Bill say ter hissef: ‘I’m gwine foll’r de one look like he got de mostes.’ He take er step dis er way, an’ he sink down so fur dat he pull, an’ pull, an’ pull, tell he pull his shoe off. Some mo’ Jackys calls him way ov’r yond’r:

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“‘Foll’r me, sonny,

I got de money.’

“So he try ter take er long step ov’r ter dem, but he sink so fur dis time dat he pull, an’ pull, an’ pull, an’ pull, but he can’ git his foots up.

“His ma’s hant ris’ up den, an’ bus’ out cryin’:

“‘Yer done los’ yer sole,

An’ yer ain’ got de gol’.’

[Pg 70]

“‘Yer done los’ yer sole,

An’ yer ain’ got de gol’.’

“Bill he keep tryin’ ter pull hisse’f up, but he done sink down ter his gallus straps.”

“Please, Mam, pull him out, p-l-e-a-s-e,” pleaded the little girl.

“Doan yer worry yose’f, his ma’s wid dat boy.”

“Yes, but she’s only a spirit.”

“Doan keer ef she is er hant, she’s his ma,—an’ de Lawd nuv’r do let dat part die out in no ’ooman. Well, dar wus Bill jes er sinkin’ an’ er sinkin’—”

“But he wusn’t any deeper than his waist, you said, Mammy,” begged Mary Van.

“He bleeg ter be er lit’le deep’r by dis time, but his ma wus cryin’ an’ beggin’ de Lawd so hard ter spar’ de boy an’ give him er-nuth’r chanct, dat er big thorney bush grow up quick[Pg 71] ’long side er Bill an’ retch out hits arms,—an’ de thorney part stick right thu Bill’s close, so Jacky-Lantern, an’ Willie Wisp an’ de res’ er de bad hants can’t pull ’im no fur’r. Bill ’gun ter see dat he wus hangin’ ov’r torment, an’ dat wus de place de gole he bin runnin’ atter stay, so he rech out an’ grab de thorney bush, he did, an’ de blood come tricklin’ down on his han’s whar de briers stick him, but his ma’s speeret come out on de thorney bush in er big, big, big ole glow wurm, an’ she say:

“‘Hole fas’,

Hit can’ las’.’

“‘Hole fas’,

Hit can’ las’.’

“He notice den dat all de uth’r lights poppin’ up an’ poppin’ out, an’ hoppin’[Pg 72] erbout, but de glow wurm’s light wus studdy.”

“Did Bill know it was his mama?” Bill’s safety was uppermost in Mary Van’s mind now.

“He doan ’zackly know hit, but he think he do, caze he know nobody ain’ gwine stick ter him atter dey’s in heb’n cep’n his ma. Darfo’ he keep his eye on de glow wurm, he do. He know dat studdy light wus his ma’s speeret.”

“Don’t let his hands bleed any more, Mammy,” she begged.

“Doan yer git too skeer’d er de blood uv ’pentence, chile. Bill done sin, an’ he got ter be born’d ergin, thu suf’in an’ mis’ry. Howsumev’r he foll’rin’ de studdy light er dat glow wurm, so ’tain’ long ’fo’ she show him er tree on t’oth’r side dat wus smooth an’[Pg 73] strong, an’ Bill tu’n loose er de bush an’ grab holt er de tree—Bob Wind he come an’ hope de tree ter lif’ Bill up,—an’ Bob give one er ole man Harricane’s blows dat take Bill clean out’n de mirey clay, an’ lan’ him on de rock.”

“Was he clear out of the swamp?”

“And where was his mama?” both children pressed their questions.

“He wusn’t clean out, but he wus clost on ter de aige—all he need is er lit’le mo’ uv his ma’s studdy light ter show him de way home,—an’ he got hit too, fur dar she wus by him on de rock, whin he come thu. She crawl ’long mouty slow b’fo’ him, caze Bill wus in er pow’ful bad fix, but her light ain’ flick’r, an’ hit keep bright an’ studdy, an’ bimeby atter er long time she lan’ him at home safe an’ soun’.”

[Pg 74]“How could it take long?” Willis was keeping tab on the time.

“Yer see, baby, yer kin nachelly fly wid Bob Wind when yer’s on de road ter Satan wid Jacky-Lantern, an’ Willie Wisp lightin’ hit up so purty fur yer; but whin yer starts back, an’ de road’s dark—an’ yer got jes one lit’le light, hit take er long time ter fine yer way erbout.”

“Was Abe and the boys waiting for Bill?” Mary Van desired to see the home reunited.

“Dey wus waitin’, but dey wusn’t settin’ down waitin’. Abe an’ dem boys had done dig dat gole out’n de cell’r an’ buy ’em er passel er mules, an’ cows, an’ chick’ns, an’ bilt ’em er fine house, an’ raise sich craps, dat de ole farm tu’n out ter be de bigges’ plantation in dem parts.”

“Did Bill get home?”

[Pg 75]“Ter be sho’, son, ain’t I done tole yer de glow wurm gwine p’int out de road fur him?”

“Did they give Bill some money, too?”

“Cose dey did, gal, der ma’s speeret light up der h’arts so bright dat dey ain’ see no rees’n ter keep all de money jes’ ’caze dey stays at home an’ fines hit.—Sut’nly dey give Bill his sheer.”

“Did the glow worm stay with them?”

“Dey ma’s speeret stay’s dar, but de glow wurm hatt’r g’long back ter de swamp ter hope de res’ er de po’ sinn’rs dat gits tang’led up runnin’ atter Jacky-Lanterns an’ Willie Wispes.”

[Pg 79]“Come on hyah, baby! Let de dog er loose—sleepy time done come ter us.”

“No, Mammy, I ain’t goin’ ter sleepy!”

“Who say you ain’t?”

“I say so, ’caus’ my papa says I’m er man! My papa don’t go ter sleepy in the day time!”

“Lordee! I bet he do if he gits er chanct. Dat dog gwine bite yer if you don’t quit foolin’ wid es tail.”

“Bray ain’t goin’ ter bite me—Mammy, you tie the bow.”

“Tie er ribbin bow on er dog’s tail?”

“Oom hoo!”

[Pg 80]“Ooom hoo? Is dat de way you speaks ter yo’ ole Mammy?”

“I says, yes, ma’m.”

“Well, gimme de ribbin!—but what you wanter tie er bow on er dog’s tail fur? Folks puts bows ’round dey necks.”

“But I want ter fool Bray, and make him think this is his head.”

“You’se er sight, you is! Who on earth but you’d er thought er tryin’ ter make er dog think es tail was es head! Nev’ mind! Yer bett’r take keer dat he don’t play er wusser joke on you, like ole Sis’ Cow, an’ Sis’ Dog, an’ Sis’ Sow, an’ Sis’ Cat done ter ole Miss Race Hoss when she try ter pass off one er her jokes on dem!”

“Did they hurt Miss Race Hoss, Mammy?”

“Dey mos’ driv her crazy, dat’s what dey[Pg 81] done!—but you wait tell I ties dis heah bow, an’ den we gwinter slip off up-stairs ’fo’ Bray wake up an’ ketch us.”

“All right, Mammy.”

Most elaborately Phyllis tied and patted the soiled blue bow.

“Now, den, Bray’s sho’ gwine hatt’r strain ’es mind ter fine out which een’ his head stays on! Jump up hyah in Mammy’s arms, so we kin run fas’ ’fo’ Bray wake up!”

Quite out of breath, Mammy reached the room up-stairs. Little Willis, interested only in the flight from Bray, did not realize the ruse she had played upon him until he found himself in his little crib bed. Open rebellion began.

“Boo hoo, boo hoo!”

“Ssho boy! You gwine wake Bray, an’ den he’s jes es sho’ es sho’ kin be ter play[Pg 82] dat trick on us dat his Gran’ Mammy Dog play’d on ole Miss Race Hoss,” remonstrated Phyllis.

“Boo hoo, boo hoo, I don’t wanter—”

“Hush, now! Lawsee! I b’lieve I heahs er race hoss comin’ down de road now! You hears him, don’t yer?”

“Oom hoo!” sobbed the little boy.

“Oom hoo?”

“Yes, ma’m!”

“Well, dat’s de way ole Miss Race Hoss soun’ when she come er single-footin’ down de road, an’ seed ole Sis’ Cow layin’ ov’r in de cornder er de pastur’ chewin’ her cud, an’ talkin’ ter ole Sis’ Sow, an’ Sis’ Dog, an’ Sis’ Cat. She look’ in de pastur’, she do, an’ see Sis’ Cow’s little calf jes’ er jumpin’ an’ er kickin’ out his b’hime legs; so she holler she do:

[Pg 83]“‘Law, Sis’ Cow, whatchu doin’ wid my little colt ov’r dar?’

“Sis’ Cow say, ‘Law, Miss Race Hoss, you sholy ain’t callin’ my po’ little calf yo’ colt?’

“Miss Race Hoss say, ‘Sis’ Cow I sho’ is s’prised you can’t tell er calf frum one er my fine colts! Jes’ look how he’s prancin’. I’m gwine jump ov’r dis fence, an’ prance ’long side him an’ let you see if we ain’t ’zackly like.’

“Wid dat, she tuck er sorter back-runnin’ start, an’ jump blip! right in de middle er de pastur’. Sis’ Cow’s little calf was so proud when Miss Race Hoss ’gun ter caper her fancy steps ’long side him, dat he clean furgit ’es ma, an’ try ter fancy step ’long side er Miss Race Hoss down de middle er de field.

[Pg 84]“Po’ Sis’ Cow beller’ an’ beller’ fur Mister Cow ter come an’ run Miss Race Hoss off, but law, Mister Cow bizzy tendin’ ter ’es bizness an’ he don’t hear ole Sis’ Cow. Jes’ den, Sis’ Dog an’ Sis’ Sow an’ Sis’ Cat sorter whisper ’mongst deysefs. Pres’ntly dey all jumps up an’ starts ter shakin’ deyse’fs whensomever Miss Race Hoss git clost ter ’em. Fus’ thing yer knows, Miss Race Hoss stop’ her fancy steppin’ an’ holler, ‘How ’pon earth come dese fleas ter git on top er me?’ She jump’ an’ she roll’, she jump’ an’ she roll’, an’ I speck she’d bin er jumpin’ an’ er rollin’ plum tell now, ef dem fleas teeth had er bin strong nuf ter er bit thu Miss Race Hosses hide, but yer see wid all de bitin’ dey bin doin’, dar wasn’t one uv ’em dat got er good clinch on Miss Race Hoss. So Sis’ Sow’s fleas say dey gwine[Pg 85] back home ter vit’als dey wus rais’d on, an’ Sis’ Dog’s fleas say dey wus gwine back whar de meat wus tender, an’ Sis’ Cat’s fleas say dey don’t see no use tryin’ ter git er livin’ off’n hoss hide when dar wus plenty er kitten meat dat would melt in yo’ mouf. So wid dat, all uv de fleas give er jump, an’ lands back on Sis’ Sow an’ Sis’ Dog an’ Sis’ Cat; an’, honey, dem fleas ain’t no sooner jumpt, dan Miss Race Hoss jump, too. She give er back-runnin’ start an’ wus ov’r dat fence ’fo’ you know’d it; an’ bless yo’ heart, she come mouty nigh ter jumpin’ on her own little colt dat had done foller’ her onbeknownst. De colt nev’r seed es ma mirate an’ car’y on so b’fo’, an’ he got so occipi’d watchin’ her dat he plum fergit ter mention he was dar. Howsomev’r, when Miss Race Hoss come er flyin’ ov’r[Pg 86] dat fence she come so close ter de little colt dat whil’st he was er gittin’ outen de way, he trip’ es own sef an’ fell er sprawlin’ flat.

“Po’ little colt commenc’ ter whinnyin’ an’ cryin’, an’ his ma was so sorry an’ miserbul dat she tuck him in her arms an’ ’gun ter pattin’ an’ er singin’ ter him jes’ like dis:

“‘Mama luvs de baby,

Papa luvs de baby,

Ev’ybody luvs de baby,

Hush yo’ bye, doan you cry,

Go ter sleepy lill’e baby.

De lill’e calfee an’ de lill’e colt, too,

Dey keeps mighty close ter dey mama,

Caze Jack Frost’s out er huntin’ all erbout,

Ter ketch lill’e chillun when dey holler.

Hush yo’ bye, doan you cry,

Go ter sleepy lill’e baby.

Mama luvs de baby,

Papa luvs de baby,

Ev’ybody luvs de baby.

[Pg 87]

All dem horses in dat fiel’

B’longs ter you lill’e baby:

Dapple, gray, de white an’ de bay,

An’ all de pretty lill’e ponies.

Hush yo’ bye, doan you cry,

Go ter sleepy lill’e baby.

Mama luvs de baby,

Papa luvs de baby,

Ev’ybody luvs de baby.’”

Softer and softer grew the crooning, until the little boy dropped into peaceful slumber.

“Now, den, de ole man’s drapt off at las’. Bless de chile, he is er man sho’ nuf; an’ de way he prove he gwine be jes’ like de res’ er de men folks, is de way he lets de wimmen fool him; eb’n er old black ’ooman like I is!”

[Pg 91]Willis drank his soup noisily, insisted upon eating with his knife, upset a glass of milk on Jane’s new Easter dress, and in the end was carried from the table kicking and screaming.

Mammy’s attempts to pacify him proved futile, and fearing the wrath of his father, she gathered up the squirming, screaming boy as best she could and ran to her own room in the rear. Letting him fall upon the bed, she breathlessly dropped into a chair, and wiped the perspiration from her face with the corner of her apron.

“Now, den, jes’ holl’r an’ kick, tell you hollers an’ kicks yo’se’f plum out.”

[Pg 92]This the boy did at a length and with a violence unbelievable, Mammy sitting all the while at the side of the bed to see that he did not roll off and humming broken pieces of song as though perfectly unconcerned. When the screaming had spent itself, and naught remained of it but long hard sniffles, Mammy began mumbling, “Well, bless de Lawd, I bin thinkin’ I wus nussin’ er fuss class qual’ty chile all dis time, an’ hyah it tu’n out I bin wor’in’ m’se’f wid one er Sis’ Sow’s mis’r’ble little pigs.”

A low wail was the only answer to this thrust.

“Hit’s de trufe! An’ I done make up m’ mine I ain’t gwine do it no longer. What’s de use er me stayin’ hyah, nussin’ er pig chile, when I kin g’long an’ nuss er fuss[Pg 93] class qual’ty chile like Mary Van, an’ I’m gwine do it, too!”

One little arm reached out to the old woman:

“Mammy!”

But she continued: “M’ye’rs is broke wid all dat pig holl’rin’! I don’t speck I ev’r is ter heah no mo’, neither!”

Sobbing and sniffling, the little boy crawled to her lap, and tried to look into her ear. She continued obstinately: “Can’t heah er thing! I knows you’se in m’ lap, but les’n I seed yo’ face I cudn’t tell ef you wus laffin’ er cryin’.”

Both arms went tight around her neck:

“Mammy, I won’t be bad no mo’!”

Pretending to weep, Mammy said pathetically:

“I wush I cud heah! I speck Miss Lucy’ll[Pg 94] tu’n me out now, ’caze m’ye’rs won’t hear no mo’, an’ den I’ll hatt’r go off ter de woods an’ die by m’se’f ’mongst de beastes; an’ I speck dey’ll kill me, ’caze I can’t heah ’em comin’! Boo hoo!”

At this, Willis’s suffering became so intense she feared to continue the punishment and so began another strain.

“But dey tells me dat ef folks whut’s bin bad prays ter de Lawd an’ kisses de place whut hurts, dat some time de Lawd makes de place well ergin; dat is,—ef de bad chile promise he ain’ gwine be bad no mo’.”

Instantly the little swollen lips moistened with blubbers, covered first one black ear and then the other.

“An’ dey got ter pray, too,” suggested Mammy.

“Now I lay me!” came in broken sniffles.

[Pg 95]Suddenly throwing up her hands, a look of rapture on her face, Mammy shouted:

“Lawsee! I b’lieve I heahs you snifflin’!” She listened carefully: “I does! Tell Mammy you loves her an’ lemme see ef I kin heah you.”

“I loves—” began the little boy, nestling in her arms.

“’Cose I kin heah, but I tell yer de Lawd ain’ gwine ter notice yo’ pray’rs no mo’, ef you keeps letting de ‘pig chile part’ er you come out.”

“I don’t want ter be er pig chile!”

“I don’t speck you does, but you sho’ ’pear terday like you come straight up fum de pigsty! Don’t you ’member dat party Miss Race Hoss giv’ an’ ’vite Sis’ Sow an’ her chilluns ter come ter it?”

Willis shook his head.

[Pg 96]“Look er hear boy, who you shakin’ dat head at?”

“I says, no, ma’m!”

“You’se late in de day sayin’ it, too. Enyhow, Miss Race Hoss giv’ er party an’ ’vite Sis’ Cat an’ her chilluns, an’ Sis’ Dog an’ her chilluns, an’ Sis’ Cow an’ de lit’le calf; an’ she sorter pass conversation wid Mist’r Race Hoss ’bout ’vitin’ Sis’ Sow an’ her fambly. Mist’r Race Hoss say long as he’s in pol’ticks an’ want ter git ’lected ergin ter be ruler er de beastes, he speck she bett’r ’vite Sis’ Sow. So Miss Race Hoss say all right! An’ she done it.

“Oh, I tell you Miss Race Hoss fix up er fine party! She had mouses fur de cat fambly, an’ dey wus nice, fine, live mouses too, an’ bones an’ meat fur de Dog fambly, an’ hot bran mash mixt wid cott’n seed[Pg 97] meal fur Sis’ Cow’s fambly, an’ she had buttermilk in er big trauff fur Sis’ Sow an’ her chilluns. An’ she pile apples, an’ carrots, an’ ev’y sort er thing in de middle er de table. An’ she had salt fur dem dat wants salt, an’ sugar fur dem whut mus’ have sugar.

“Well, de fuss uns ter come wus Sis’ Cat an’ her chilluns. Sis’ Cat had done wash’ her kittens’ faces jes’ es clean an’ put dem mitt’ns on ’em dat yo’ ma read ter us erbout.

“Den hyah come Sis’ Dog an’ her fambly. Dey all had bows ’roun’ der necks an’ look mouty gran’! Sis’ Cow an’ de calf wus curri’d slick es glass, an’ I tell yer Miss Race Hoss wus glad her an’ de little colt had dem ribbins tied up in der manes, ’caze Sis’ Cow was sho’ pressin’ ’em in slickness.

“Ole Brer Bar he come down fum de[Pg 98] woods ter ’tend ter de dinin’ room an’ see dat ev’ybody git de right vit’als.

“Atter dey bin waitin’ fer er spell, Brer Bar ’nounce dat soon es Sis’ Sow come de party wus ready.

“All uv ’em want ter go ter eatin’ dat minit, ’caze dem cats smell dem mouses, an’ dem dogs moufs jes’ er dreanin’ wid de smell er dat meat; but dey sets dar like dey done fergit all erbout vit’als, ’caze dese heah wus qual’ty animals wid manners, I tell yer.

“Pres’ntly Miss Race Hoss low dat she see Sis’ Sow comin’ now, an’ she seen her, too, fur hyah come Sis’ Sow an’ all her chilluns er runnin’ ev’y which er way, wid mud all ov’r dey backs. Some uv ’em wus wet an’ some uv ’em wus dry. Dey come er runnin’ an’ none uv ’em ain’t nuv’r stop ter pass howdy wid Miss Race Hoss, ’caze dey[Pg 99] smell de vit’als, an’ dey ain’t got nuff manners ter hide de pig in ’em. Dey come er rootin’ an’ er gruntin’ all ’roun’ b’hime folks an’ b’fo’ fokes, tell dey pass too close ter Sis’ Cat’s chilluns, fur dey sorter raise up dey backs an’ bushy out dey tails, an’ raise up dey paws, but Sis’ Cat she sorter growl sof’ an’ dey passify deysefs an’ sets still. Sis’ Dog’s chilluns wanter snap es dey come er trompin’ on top er dey foots, but dey ’strains deysefs ’caze dey wus fuss class qual’ty dogs.

“Brer Bar see Sis’ Sow rootin’ an’ gruntin’ her way ter de table, so he ’nounce fur ’em all ter come in ter de party. He sorter push Sis’ Sow an’ her chilluns off ter de buttermilk trauff. De uther folks dey sets down at de table an’ acts like fuss class folks does, but Sis’ Sow an’ her pig chilluns ain’t seed[Pg 100] dey vit’als ’fo’ all uv ’em try ter git in de trauff wid dey foots. Dey pushes an’ tromps ’pon one ’nuther, an’ squeals, an’ eats loud like you done terday!”

The brown eyes fell and an humble little voice said, “I ain’t gointer do it no mo’.”

“De Lawd knows I’m glad to hear it. Well, Sis’ Sow an’ dem, quoil an’ make so much fuss, tell de uther fokes can’t pass no conversation er tall, tell pres’ntly Sis’ Sow an’ de pigs eat up all dey vit’als an’ dey come gruntin’ an’ er rootin’ fur mo’. Dey spy dem apples an’ things on de table, an’ ’fo’ yer knows it, dem pig chillun wus ’pon top er dat table.

“Wid dat, Brer Bar git so mad he slap ’em off fas’ es dey gits on; but de fust un he slap’ off fell right in ’mongst Sis’ Cat’s kittens. Whoopee! Dem kittin chillun [Pg 101]fergits all ’bout manners an’ ’gins scratchin’ an’ fightin’ same es pigs. Sis’ Dog’s chilluns jes’ nachelly cudn’t stan’ no sich er strain on dey manners es dat, an’ ’fo’ yer kin say ‘Jack Robson,’ de kittins an’ de puppies an’ de pigs wus er squealin’, an’ er barkin’, an’ er spittin’, an’ er growlin’, tell you can’t hear yo’ ye’rs. Sis’ Sow start ter runnin’ down de road wid de pigs atter her, an’ de puppies atter de pigs, an’ de kittins atter de puppies. Wid dat de little calf git ’cited an’ he start ter kickin’ out his b’hime legs, which happen ter hit de lit’le colt, an’ he r’ar’ hissef back an’ come down on de calf, an’ bofe uv ’em take out down de road er holl’rin’ an’ er kickin’, an’ er twistin’ deysefs like you done terday!”

Again the brown eyes fell.

“Atter all de chilluns done loss dey [Pg 102]manners, dey ma’s sets up lookin’ at one nuther like dey loss dey las’ frien’. Pres’ntly Miss Race Hoss say hit’s all her fault, ’caze she had no biznes ter mix up qual’ty folks wid pig folks.

“Wid dat Sis’ Cow an’ Sis’ Cat an’ Sis’ Dog speak up. ‘No, Miss Race Hoss, ’tain’t yo’ fault, an’ it ’tain’t our chilluns fault, it’s jes’ dem pigs’ fault.’ Jes’ den ole Brer Bar ris’ up an’ clap his han’s an’ laff like he splittin’ his sides. Miss Race Hoss look ’stonish’ dat he act dat er way, an’ she ax him whut ail him. Soon es Brer Bar kin stop laffin’, he say: ‘Youall thinks yo’ chilluns ain’t got no pig in ’em, does you?’ den he start ter laffin’ ergin. Miss Race Hoss r’ar’ back herse’f an’ say, ‘Brer Bar, you done fergit whar ’bouts you’se at; ’member you’se ’mongst fuss class qual’ty!’ Den dey [Pg 103]all throws dey heads back an’ tu’ns dey noses up at po’ Brer Bar. Brer Bar git mad den an’ he stop laffin’ an’ say, ‘Yo’ chilluns ain’t de onliest uns got pig in ’em! All youall got it, too. Ev’ybody got it. Some folks got mo’ en uthers got; all dis hyah mann’rs you’se braggin’ ’bout ain’t nuthin’ but er kiv’r ter hide de pig dat’s in yer. Keep er way fum de pigs ef you don’t wanter show yo’ pig side.’

“WID DAT DEY ALL UV ’EM LOSE DEY MANNERS

AN’ START TER ’BUSIN’ BER BAR SCAND’LOUS”

“Wid dat dey all uv ’em lose dey manners an’ start ter ’busin’ Brer Bar scand’lous. Sis’ Cow beller’ out her madness, an’ Sis’ Cat mew an’ spit out her’n, an’ Sis’ Dog growl an’ bark out her’n, an’ Miss Race Hoss jes’ r’ar’ up an’ foam at de mouf.

“Brer Bar look like he fixin’ ter hu’t sumbody, den he amble off t’ards de woods he did, an’ den tu’n hissef ’roun’ an’ holl’r, ‘I[Pg 104] tole yer so!’ Jes’ lis’n ter all er youall right now, actin’ wusser en dem pigs in de buttermilk trauff.”

“An’ Brer Bar speak de trufe! An’ he speak de trufe when he say all us got er pig side, too.”

“My mama ain’t!”

Phyllis hesitated: “No, I don’t speck she is; dat is, ef she is, her ’ligion done wash it all out, ’caze yo’ ma think’ mo’ ’bout ev’ybody else ’fo’ she do herse’f,—but you got er pig side, an’ ef you don’t take keer hit’ll grow ter be er hog side, too, dat you nuv’r is ter git nuff manners ter hide neither. Come on an’ go finish yo’ dinner, boy, an’ let Mammy eat her’n.”

[Pg 107]Phyllis was dozing on the top step of the side veranda while little Willis, in the gravel walk below, was playing with a Noah’s Ark. The animals were in grand parade when one of them met with an accident. Willis thought a moment, then, taking the loose ends of a string tied to one of the fuzzy toys, he climbed the steps to where Phyllis had just fallen in a peaceful nod against the pillar. He clumsily slipped the string between her open lips, and, with a slap and sputter, Mammy opened her eyes.

“Name er de Lawd, boy, whut is you tryin’ ter do?”

[Pg 108]“I want you ter be er billy goat.”

“You wants sumthin’ I nuv’r is ter be. I’m willin’ ter be er hoss an’ on er pinch I’ll be er mule, but dey ain’t no time I’m willin’ ter be no ole billy goat fur nobody.”

“Please, Mammy,” laying a hand on her cheek in an effort to pull her face to him, “m’ billy goat’s got his legs broke, an’ I won’t have any goat if you don’t be one.”

“How come you don’t tu’n one dem dogs in er goat?” suggested Phyllis, her face obstinately averted.

“They haven’t got any horns!”

“I ain’t got no horns neether,” asserted Mammy.

“But you can make some,” persisted Willis.

“You think I’m gwineter pull dis bandanner off an’ roll my ole gray wool inter[Pg 109] horns, does you?” chuckled the old nurse.

Willis nodded.

“Well, you foolin’ yo’se’f, dat’s all I got ter say.” But when Willis began to fret, Mammy relented: “I tell yer dat dog won’t know ’esse’f fum er goat, ef you calls him goat; ’caze I knows erbout er dog an’ er goat dat can’t tell t’other fum which.”

“No you don’t,” objected the tormentor tugging at her arm.

“I tells you I does, ’caze one day Mister Man went out ter hunt er dog an’ er goat fur his lit’le boy. He see Sis’ Dog an’ her fambly on de side er de road, an’ dey ’pears ter be in er mouty commotion ’bout sump’n. Mister Man holler’ an’ ax whut ail ’em. Sis’ Dog say she foun’ one er Sis’ Nanny Goat’s chilluns layin’ out in de pastur’ des er blatin’ all by ’esse’f, an’ she[Pg 110] dunno whut ter do wid it. Mister Man say, ‘I’ll take keer uv it, an’ I’d like moutily ter take keer er one er yo’ chilluns, too.’ Sis’ Dog tell him ‘surtiny,’ dat it ’ud make her turr’bul proud fur one er her chilluns ter live up at his fine house. So Mister Man liftes de goat an’ de puppy up on Miss Race Hosses back ’long side er him an’ flies ’crost de country ter his house. When Mister Man’s ole lady see him, she th’ow up her han’s an’ say, ‘Name er de Lawd, Mister Man, whut you specks ter do wid dat goat?’ Mister Man say: ‘Oh! I’ll des put it out hyah wid de puppy an’ raise ’em bofe tergether.’”

“Wasn’t the little boy glad his papa kept the goat?” interrupted Willis.

“Is you glad I’m tellin’ dis tale?”

“Yes’m.”

[Pg 111]“Dat’s ’zackly de way Mister Man’s boy feel, ’ceptin’ mo’ so. Dey puts er pan er milk out in de cow house, an’ bofe uv ’em eats outen it tergether. When dey gits big ernuf ter eat like sho’ nuf beastes, de little boy puts goat feed fur de goat an’ dog vit’als fur de dog.”

“What’s the dog’s name?”

“He wus jes’ name Collie Dog when he live wid his mammy, but when he start ter livin’ wid white fokes, de lit’le boy name ’im Ned.”

“An’ what’s the goat’s name?”

“He ain’t got nuthin’ ter do wid dat, ’caze de Lawd done already name him Billy. Well, when Billy Goat look’ at his feed, an’ Ned Dog look’ at his vit’als, dey bofe feels mouty proud, ’ceptin’ dey don’t seem ter make out howcum it ain’t mix’d tergether; so[Pg 112] Billy he take an’ run over an’ try ter eat bones an’ meat, an’ Ned he run ter Billy’s box an’ try ter eat hay an’ bran mash; an’ dey keep on tryin’ ter eat one nuthers vit’als long es dey live’. Pres’ntly, Billy grow so big dat he ’gun ter grazin’ roun’ ’mongst de flow’rs an’ grass, an’ I speck he run in de house sumtimes, too, but it ’pears dat flow’r buds tas’e mo’ nicer ter ’im dan grass; so Mister Man’s old lady ’gun ter quoil an’ mirate an’ tell him, ‘You des got ter tetter dat goat!’”

“I don’t want ’im ter tetter Billy!” exclaimed the child, and his brown eyes filled with tears.

“Pshaw, boy, er tetter ain’t nuthin’ ter hu’t nobody! It’s des er rope you ties roun’ de horns er beastes an’ de uther een’ you ties ter er stob in de groun’! Well,[Pg 113] when Billy find ’esse’f tied ter dat rope so he can’t go in de house and can’t go in de flow’r gyarden, he des cry an’ cry. Ned Dog try ter stay wid ’im much es he kin; but when he see Mister Man an’ de little boy settin’ off down de road on Miss Race Hoss an’ de little colt, his foots des nachelly go bookety! bookety! b’hime ’im ’d’out knowin’ it. His heart tell him ter g’long back an’ stay wid Billy, but his foots say dey ain’t er gwine do no sich er thing. ’Cose he cudn’t hep ’esse’f ef his foots ’fuse ter take ’im home. Atter while, when he gits back, Billy done cry ’esse’f plum sick. He say he don’t see howcum he tied up an’ Ned Dog ain’t; an’ Ned Dog say he don’t neether; ’caze you see Ned think Billy’s er dog an’ Billy think ’esse’f er dog, too. Dat’s de way wid some fokes. Heap uv ’em[Pg 114] thinks dey’s big dogs when dey ain’t nuthin’ but er old goat!” Mammy concluded with emphasis.

“Go on, Mammy,” demanded Willis, pushing her hand off of the curl she was trying to straighten.

“Ain’t dat ernuf? I done prove’ you kin make er goat outen dat Noah’s ark dog.”

“Yes, but I want the little boy ter let Billy loose.”

“Well, his ma’ll give him er spankin’ ef he do. Dat boy darsent ter tech dat tetter. Long ’bout atter dinner time, Ned he git so miserbul lis’nin’ ter Billy hollerin’ dat he ’gun ter gnaw an’ pull at de stob; den he try ter scratch it up; but it was too deep; so he take an’ go ter pullin’ at de rope ergin’; an’ bimeby de knot come off. He ketch de knot in his teef and den he tell Billy ter[Pg 115] g’long whar he’s er mind ter. Billy kick up es b’hime legs an’ fly down de road wid Ned Dog b’hime him holdin’ on ter de rope. Billy he eat all ’long de road, an’ Ned Dog foll’r ’long b’hime wharsomever Billy choose ter go, ’caze yer see Ned feel de ’sponsibility er loosin’ Billy. Atter while, Ned Dog beg Billy ter come on an’ go home! He tell ’im his jaws nigh ’bout broke clampin’ on dat knot. But Billy say he ain’t er gwine, tell he eat ’esse’f plum full er dem flow’r buds. No, Lawd, Billy ain’t thinkin’ bout Ned long es he kin joy es own sef. Ned he ’gun ter howl an’ bark wid de jaw ache, but Billy too full er ’esse’f ter notice Ned. Yes, Lawd, Billy des like some fokes I knows, too.”

“Me, Mammy?” demanded the intent little boy.

[Pg 116]“Yes, I speck de cap fit you er heap er times, but you wusn’t de pusson I had m’ mine on des den,” replied Mammy complacently. “Billy keep er gwine on, an’ Ned des er draggin’ ’esse’f erlong wid de jaw ache tell bimeby, dey comes ter de old log fence ’roun’ de pastur’. Billy he try ter jump de fence, but Ned he crawl thu; but yer see Billy can’t jump high ernuf ’caze Ned’s pullin’ de rope on de uther side, so Billy gits tangled up on one er de rails. Ned he run back when he see Billy’s hangin’; but he gits back thu er diffunt hole ergin, an’ dat twistes de rope so tight dat Billy gits in er mouty bad fix ’fo’ you knows it. He ’gun ter blate an’ holl’r an’ Ned drop’ de rope an’ ’gun ter howl; but dat nuv’r done no good, an’ it nuv’r do, do no good in dis woel.”

[Pg 117]“What, Mammy?”

“Jes’ ter stan’ up an’ holler an’ cry like you does sometimes! You got ter go ter work an’ do sumthin’ ef you ’specks ter ontangle yo’se’f in dis woel’, an’ dat’s whut come ’cross Ned’s mind atter he stan’ up an’ holler hisse’f hoarse. He lope out an’ run home, he do, an’ he bark at Mister Man an’ run out to’ards de road. He bark’ at de lit’le boy an’ run out ergin; but none uv ’em can’t make out howcum he act so cur’us. He run out in de back yard an’ howl an’ bark, an’ de lit’le colt ax him whut ails him, he tell ’im Billy’s mos’ chok’d ter death, hangin’ on de pastur’ fence. De colt give er jump ov’r de back fence an’ him an’ Ned take out, jes’ er t’arin’ down de big road. De lit’le boy an’ Mister Man seed de colt break loose an’ dey flew atter him an’ all[Pg 118] uv ’em got ter Billy jes’ in time ter keep ’im fum chokin’ ter death.”

“Did Billy die?” asked the little boy in anxiety.

“Nor, honey, ’caze he nuv’r had rope ernuf; but ef he had er had er little mo’ rope him an’ all de uther foolish folks like ’im wud er bin dead long ergo!”

[Pg 121]The side lawn was the scene of a noisy fray between the old house cat and big dog, Bray. Servants from the neighborhood had quickly gathered to urge on the sport. Some of the children, Willis among the loudest, were crying and beseeching the men servants to save “poor Kitty,” which they reluctantly did to the extent of allowing her to escape up an old crab apple tree.

“I wush ter de Lawd he had er kilt her,” said Phyllis, letting her rheumatic limbs down by degrees to a sitting posture on the grass, “’Ceitful old thing, I don’t blame Bray!”

[Pg 122]“I love my Kitty!” cried Willis as he ran to the tree. There he earnestly advised the cat to stay just where she was until Bray went to sleep. A few of the larger children lingered expecting another fight, as Bray continued to bark and jump about the tree.

“You ne’en ter tell dat cat ter take keer er herse’f! She des settin’ up dat tree glis’nin’ dem old green eyes on Bray an’ sayin’ ter ’erse’f: ‘Nuv’r mind, I’m gwine fix you soon es I git down fum hyah!’”

“What can she do, Mammy Phyllis?” asked one of the larger girls. “She’s too little to hurt Bray!”

“Yas, an’ ole Sis’ Cat wus lit’ler’n her, an’ yit she come mighty nigh ter fixin’ Ned Dog an’ Billy Goat, too! Doan nuv’r put no ’pindence in Sis Tabby’s fokes.”

“Oh, Mammy Phyllis, please tell us[Pg 123] about Ned Dog,” and the children gathered around her pressing the request.

“Doan ax me ter tell nuthin’ long as Willis keep foolin’ roun’ Bray wid dat switch!”

Mammy pretended to rise, but two of the older children ran and coaxed Willis to sit by them and listen to the story. “Now, Mammy Phyllis, go on, he’s going to sit still, ain’t you Willis?” said one.

“I want ter whoop Bray,” muttered Willis only half satisfied.

“Atter I tells you how ’ceitful Sis’ Cat act ter Ned Dog, I boun’ you’ll change yo’ chune! ’Member dat party Miss Race Hoss give an’ how it broke up wid all uv ’em quoilin’ an’ ’busin’ ole Brer Bar? Po’ Brer Bar nuv’r got no vit’als neeth’r. Well, when Sis’ Cat lef’ dat party, she wus[Pg 124] so mad she cudn’t walk straight! She come er flyin’ down de big road right catacornder’d! Dat is, she run in de road one minit, an’ de nex’ un, she fotch up on de side er de mount’in; den hyah she come back ergin in de road! Well, one uv de times she lit on de mount’in she fotch up right in front er Mist’r Rattlesnake’s house. Mist’r Rattlesnake had des got out er bed an’ stuck his head out’n his house ter git er little fresh air, when Sis’ Cat come blip! right in his face! He lick’ out his tongue an’ say:

“‘Name er de Lawd, Sis’ Cat!’

“Sis’ Cat say: ‘Name er de Lawd, Mist’r Rattlesnake! Howcum you gittin’ up dis time de year?’

“‘I thought I heerd m’ ’larm clock go off,’ he say.

“‘You ain’ hyah no thunder Mister [Pg 125]Rattlesnake! You kin g’long back ter baid an’ take er three weeks’ nap,’ sez Sis’ Cat.

“‘I’m sho’ I heerd thunder er som’thin’ pow’ful like it,’ sez Mister Rattlesnake.

“Sis’ Cat tell him: ‘You des heah de breakin’ up uv Miss Race Hoss’s party! Dat’s whut you heah! Brer Bar act so outlashus we des hatt’r ’buse him an’ run him off!’

“Mist’r Rattlesnake set an’ look at Sis’ Cat er minit, ’caze yer see he ain’ wake’ up good yit. Den he lick out es tongue an’ say: ‘Sis’ Cat, you sholy ain’ th’owin’ erway no fren’s is yer? I knows I ain’ got narry single fren’ an’ I knows you got pow’ful few yo’se’f! ’Pears ter me yer better g’long an’ eat up dem words you sed ter Brer Bar!’ Den he lick out his tongue ergin an’ go on back ter baid.

[Pg 126]“Sis’ Cat set right dar an’ study, she do! Den she make up her mind ter take Mist’r Rattlesnake’ ’vice. She slunk eroun’ sorter soft an’ sneakin’ like thu de woods tell she come ter Brer Bar’s house. She bum! bum! on de do’ an’ Brer Bar ax, ‘Who dat?’

“She say: ‘Sis’ Cat.’

“‘Is you Sis’ Wile Cat er Sis’ Tabby Cat?’ ax Brer Bar.

“‘Sis’ Tabby Cat.’

“‘You’se at de wrong do’, Sis’ Tabby Cat,’ sez Brer Bar.

“Sis’ Cat start ter cryin’: ‘Oh! Brer Bar! Brer Bar! please lemme come in! I’m mos’ dead, Brer Bar!’

“Brer Bar say: ‘You bett’r git erway fum hyah, Sis’ Cat, ’caze I’m li’ble ter eat enythin’ I lays my paws on! I nuv’r had ernuf ter eat at de party, an’ I ain’ pervide m’[Pg 127] fambly wid nuthin’ ter eat, an’ we’se all s’ hungry dat we’se dangus’, Sis’ Cat!’

“Sis’ Cat keep on cryin’: ‘I know’d dat Brer Bar;—I know’d you an’ yo’ fambly was hongry, an’ dat’s howcum I ter come, Brer Bar! I come ter tell you whar some good vit’als was des waitin’ fur yer!’

“When Brer Bar hear dat, he sorter crack de do’ an’ poke his nose thu: ‘Sis’ Tabby Cat,’ he say, ‘you smells good ernuf ter eat yo’se’f!’

“Sis’ Cat mos’ skeerd ter death when she heah dat, an’ she mos’ die when she feel Brer Bar’s mouf dreanin’ an’ drippin’ on her back; so she stop’ cryin’ an’ sorter back off kinder easy like an’ tell Brer Bar dat Ned Dog got de fattes’ Billy Goat he ev’r seed; an’ ef he’d come down ter de ole sweet-gum tree in Mist’r Man’s pastur’ ’bout[Pg 128] dark, she’d have him er whole tree full er honey, an’ de Billy Goat, too!”

Willis’s lips began to tremble. He suddenly left his place among the children and falling on Phyllis’s breast, sobbed aloud.

“Brer Bar ain’ eat de goat yit! He ain’ eb’n got fur es de sweet-gum tree! Set hyah in Mammy’s lap so nuthin’ can’t git you, an’ lis’n ter de res’ er de tale!” Snuggling him in her arms, she continued: “It nuv’r tuk Sis’ Cat long ter light out fum Brer Bar’s house, I tell yer! Dat dreanin’ mouf er his’n skeer’ her so bad dat she nuv’r tetch de groun’ mo’n six times ’fo’ she wus plum out’n de woods. Den she come er cropin’ up ter Mister Man’s house. She look all erroun’ she do, an’ see Ned Dog wusn’t at home; den she g’long in de barn whar Billy wus huntin’ fur sumthin’ ter[Pg 129] eat. She take er seat in de winder by de little colt’s stall. Bimeby she say, ‘Billy, Miss Turkey Hen’s givin’ er mouty fine party ternight, down at de old sweet-gum tree in de pastur’ an’ she tole me ter ax you ter come.’ Billy couldn’t fine nuthin’ ter eat in de barn but some old straw Miss Race Hoss had done slep’ on, so he turn’ roun’ mouty quick when Sis’ Cat tell him he wus ax ter er party. He sorter laff an’ say: ‘I wond’r howcum her ter ax me.’

“Sis’ Cat say: ‘Caze she say you’se de fines’ an’ slickes’ uv all Mister Man’s beastes; an’ she gwine have some nice lit’le tender rose bushes fur you ter eat, an’ er heap er fine vit’als you loves.’

“Billy Goat des switch his tail an’ grin, ’caze yer know he wusn’t nuthin’ but er man goat, an’ ’cose he b’lief all de comp’ments[Pg 130] Sis’ Cat choose ter stuff ’im wid. An’ all de men fokes is des de same, tell dis day! ev’y Lord’s blessed one uv ’em! When Sis’ Cat see she done turn Billy’s head plum roun’ she tell ’im not ter tell Ned Dog erbout de party, ’caze Miss Turkey Hen say she ain’ got ’nuf room but fur des one uv de fambly. Den, when Sis’ Cat heah Ned Dog er comin’, she lit out, ’caze she nuv’r want ’im ter know dat she had enything ter do wid Brer Bar eatin’ Billy Goat. Yer see Sis’ Cat wus tryin’ ter keep in wid bofe sides.”

Slipping her fingers under the bandanna kerchief bound about her head, and scratching slowly, Mammy chuckled to herself: “Dey’s er heap er fine folks in dis hyah town des like Sis’ Cat, too! Yes, Lawd, er heap uv ’em!”

[Pg 131]“Don’t talk about people! We just want to hear about beastes!” urged little Mary Van.

“I hatt’r do it sometimes, chile, ’caze fokes an’ beastes has er heap er symptoms des erlike! Well, bless de Lawd, Billy ain’t no sooner seed Ned ’fo he ’gun ter brag erbout de party.

“‘Whose party?’ sez Ned Dog.

“‘Miss Turkey Hen’s havin’ er fine party down at de ole sweet-gum tree ternight ’bout dark,’ sez Billy.

“Ned Dog think Billy tellin’ er story, an’ he say, ‘Sis’ Turkey Hen ain’ givin’ no party ternight! I done see Mist’r Turkey Gobble an’ de chilluns in bed when I come thu de peach orchard an’ old Miss Turkey Hen, she wus des tyin’ her nightcap on her own se’f.’

[Pg 132]“But, yer see, Billy wus too hard-head’d ter lis’n ter enybody, so he up an’ say, ‘I can’t hep whut you seen; Sis’ Cat say she gwine have spechul vit’als fur me, an’ I’m gwine!’ Den Billy walk up an’ down breshen de flies off’n his back wid his long tail.”

Seeing that some objections were about to be raised as to the length of the tail, Phyllis hastened to add: “In dem days goats had tails des like hosses. Soon es Billy menshun Sis’ Cat’s name, Ned Dog tell him Sis’ Cat layin’ er trap fur him; but ’tain’t no use ter argufy wid hard-head’d fokes like Billy, so Ned Dog let ’im g’long ter de party; but he crope close on b’hime ’im, an’ on de way, he come up wid Mist’r Bloodhoun’ an’ ax ’im ter g’long wid ’im. Mist’r Bloodhoun’ say he pow’ful broke down trailin’ er runaway[Pg 133] nigger all day, but ef Ned was ’spectin’ er rompus he ’speck he’d hatt’r jine him. Bimeby, when Billy wus mos’ down ter de sweet-gum tree, dey hides deyse’fs in er clump er red haw bushes. Ole Brer Bar he had done come down fum de mount’in early, an’ wus standin’ b’hime de tree des er gorgin’ ’esse’f wid honey an’ peepin’ out, lookin’ fur Billy Goat. When he see Billy come switchin’ ’esse’f ’cross he pastur’, he ’gun ter fidgitin’ so he can’t wait ter git es teef in him, an’ he bus’ out fum b’hime de tree an’ come er runnin’ t’ards Billy. Billy wus so skeered he jes’ had sense ernuf ter turn ’esse’f roun’! Brer Bar ketch ’im by de tail. Brer Bar pull, an’ Billy pull. Billy pull, an’ Brer Bar pull! Bimeby, de tail come off in Brer Bar’s claw. Den Billy lit out; but Brer Bar grab ’im by de b’hime leg. Des[Pg 134] den Mister Bloodhoun’ an’ Ned Dog wus on top er Brer Bar! Ned Dog grab Brer Bar’s paw in es teefs an’ Brer Bar drop Billy an’ grab Ned by de ye’r an’ wus mos’ clampin’ es jaws on Ned’s haid when Mist’r Bloodhoun’ clinch ’im by de th’oat! Brer Bar ax Mister Bloodhoun’ please ter turn es th’oat loose, dat he got sumthin’ ter tell ’im! Mist’r Bloodhoun’ ’nounce: ‘I won’t turn you plum loose, but I’ll hol’ yo’ th’oat easy like tell you kin ’splain yo’se’f!’

“Den Brer Bar splainify ’esse’f an’ beg so hard, tell bimeby dey ’scuses ’im, an’ he amble’ on home fas’ es he kin. Den dey come on home ter settle matters wid Sis’ Cat. Sis’ Cat was er settin’ by Billy moanin’ wid him ’bout losin’ es tail.”

“Did his tail ever grow out any more?” asked a sympathetic boy.

[Pg 135]“No, honey, goats ain’t nuv’r had no tails ter speak uv sense dat day; but hoopee! hyah come Ned Dog an’ Mister Bloodhoun’! Dey come er yelpin’ wid dey tongues er hangin’ out. Dey pounce right whar Sis’ Cat wus settin’, but dey ain’t pounce quick as Sis’ Cat kin jump; ’caze by de time dey hits Sis’ Cat’s seat, Sis’ Cat, she was plum on top er de cow house, standin’ dar wid ’er back up, an’ her tail bushy out. Ned Dog dare her ter come down an’ splain ’erse’f; but Sis’ Cat say she ain’t got nuthin’ ter ’splain, an’ what’s mo’ she doan take no dog’s dare. An’ dat howcum dey quoil an ’spute whensumever dey meets tell dis day.”

“But, Mammy Phyllis, all cats are not as mean as ole Sis’ Cat,” ventured a little girl.

“Honey, my gran-mammy wus black! What color is I?”

[Pg 136]“Black!” chimed all the children.

“An’ dat crab apple tree,—what sort er apples does you git off’n hit?”

“Crab apples!” was the answer.

“Well, ole Sis’ Cat was mean an’ ’ceitful, an’all ’er chillun is gwine ter be des like her long es I stays black an’ dem crab apples stays sour. Now run erlong,—dere’s de fust bell!”

[Pg 139]Phyllis was eating her dinner under the cherry tree near the kitchen door. Willis seated himself on the grass in front of her.

“Mammy, you swallowed a fly then,” he said with earnestness.

“Look er heah, boy, ain’t you had ernuf ter eat, dat you got ter set hyah an’ sight ev’y piece uv vit’als I puts in my mouf?”

“Well, you didn’t want to eat a fly, did you?” he answered defensively.

“Ef I eats er fly, hit’s me doin’ hit, ain’t hit?” with a leg of a chicken poised half way to her mouth.

“But Mama said they’d poison you.” Willis was in trim for argument.