This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

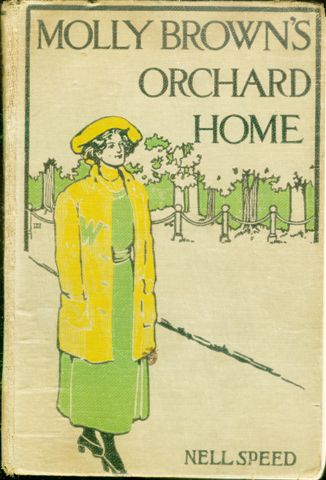

Title: Molly Brown's Orchard Home

Author: Nell Speed

Release Date: February 19, 2007 [eBook #20632]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOLLY BROWN'S ORCHARD HOME***

CHAPTER I. Letters

CHAPTER II. Bon Voyage

CHAPTER III. The Deep Sea

CHAPTER IV. What Molly Overheard

CHAPTER V. Paris

CHAPTER VI. La Marquise

CHAPTER VII. The Faubourg

CHAPTER VIII. The Opera

CHAPTER IX. The Postscript

CHAPTER X. Bohemia

CHAPTER XI. A Studio Tea in the Latin Quarter

CHAPTER XII. The Green-eyed Monster

CHAPTER XIII. A Julia Kean Scrape

CHAPTER XIV. Coals of Fire

CHAPTER XV. Mr. Kinsella's Indian Summer

CHAPTER XVI. Apple Blossom Time in Normandy

CHAPTER XVII. The Ghost in the Chapel

CHAPTER XVIII. The Prescription

CHAPTER XIX. Fontainebleau and What Came of It

CHAPTER XX. More Letters

CHAPTER XXI. Molly Brown's Orchard Home

Other books by A.L. Burt Company

From Miss Molly Brown of Kentucky to Miss Nance Oldham of Vermont.

Chatsworth, Kentucky.

My dearest Nance:

Our passage to Antwerp is really engaged and in two weeks Mother and I will be on the water. I can hardly believe it is I, Molly Brown, about to have this "great adventure." That is what Mother and I call this undertaking: "Our great adventure." Mother says it sounds Henry Jamesy and I take her word for it (so far I have not read that novelist), but he must be very interesting, as Mother and Professor Green used to discuss him for hours at a time.

Our going is not quite so happy as we meant it to be. Kent can't come with us as we had planned, but will have to stay in Louisville for some months, and may not be able to leave at all this winter. There is some complication of our affairs, that makes it best for him to be on hand until the matter is settled. I remember how interested you were in the fact that oil was found on my mother's land and that she expected to realize an independent income from the sale of the land, also pay off the mortgage on Chatsworth, our beloved home. Don't be too uneasy, the oil is there all right enough and we shall finally get the money, but the arrangement was: so much down and the rest when the wells should begin operation.

The first payment Mother used immediately to pay the mortgage, but the second payment has not been made yet, as Mother's sister, Aunt Clay, living on the adjoining place, has got out an injunction against the Oil Trust as a public nuisance, and all work in the oil land has had to be stopped for the time being. The lawyer for the Trust told my brother, Paul, that Aunt Clay has not a leg to stand on, but of course the law has to take its leisurely course, and in the meantime the money for Mother is not forthcoming until the wells are in operation. Aunt Clay is in her element, making everyone as uncomfortable as possible and engaged in a foolish lawsuit. She is always going to law about something and always losing. We are devoutly thankful that her suit is with the Trust and not our Mother, as we know that Mother is so constituted she could not stand up against a member of her family in a lawsuit. I truly believe she would let Aunt Clay take the oil lands and all the rest of Chatsworth, rather than have a row over it.

This property, where the oil was found, was given to Mother by Aunt Clay when she settled up Grandfather Carmichael's estate. Of course she considered the property of no value or she would never have let it out of her clutches, and as executrix and administratrix of the estate she had absolute power. Now that she sees it is worth more than all the rest put together, she is in such a rage with Mother that it is really absurd. She does not want us to go to Paris and is furious at the idea of Kent's "stopping work," as she calls it. She has got out this injunction just to keep us from going, I believe, as she is intelligent enough to know there is no use in trying to get ahead of a mighty Trust, and they will have to win in the end; but she had an idea that we would not go unless we had plenty of money to have a good time on. She little knows our Mother, in spite of being her sister.

Mother says she believes it will be more fun and easier to economize in Paris than in Kentucky; and she is as gay as a lark over the prospect. Kent may be able to come later and take that much talked of and longed for course in Architecture at the Beaux Arts. In the meantime, he is very busy and, as he says, "making good with his boss." Mother refuses to discuss Aunt Clay's behavior and actually goes to see her as though nothing had happened; but I know she has had many a sleepless night, brooding over her sister's unsisterly act.

I am longing to see you, dearest Nance, and wish you could manage to meet me in New York before we sail, but if you can't, be sure to have a letter on the steamer for me. We are going on a slow boat to Antwerp. We think the long sea trip will be good for Mother, who is tired out with all this worry and the work of getting Chatsworth in condition to leave; and besides, the slow boats are much cheaper. Laurens is the name of our boat, sailing from Hoboken. I will write you from Paris, where Julia Kean is already installed and hard at work on her beloved art.

I am afraid you will think I am horrid about Aunt Clay. Mother says she is the only person she ever knew me to feel bitter about. So she is, but then she is the only person who was ever mean to my beloved Mother. Maybe when my hair turns gray I can be as much of a lady as Mother is, but so far I am too red-headed to be a perfect lady.

I am going to miss you, Nance, more than I can tell you. We have been roommates for five years at college, and never once did we have a shadow of a disagreement. Of course we occasionally got in a kind of penumbra. Once I remember when I was touchy because you called Professor Edwin Green an oldish person, but my pettishness only lasted "like a cloud's flying shadow," and that ought not to count.

I think you are splendid to make such a happy home for your father and I know you are a wonderful housekeeper. Please give him my kindest regards. Kent drove Mother and me into Louisville to hear your mother speak at the Equal Suffrage Convention. She was simply overpowering in her arguments, and converted Kent in five minutes. I wish Aunt Clay, who is such an ardent Anti, had heard her. We were so sorry Mrs. Oldham could not come out to Chatsworth to visit us, but she did not have the time. I must stop. I have written two stamps' worth already.

Ever your devoted friend and roommate in heart,

Molly Brown.

To Miss Molly Brown, Chatsworth, Kentucky,

From Miss Julia Kean, Paris, France.

71 Boulevard St. Michel, Paris.

Molly dear:

The news that you and your mother are to sail in a few weeks threw me into the seventh heaven of happiness,—I am already on the seventh floor of a pension with not much more of an elevator than the tower of Babel had. Mamma and Papa brought me here and installed me and then shot off to Turkey, Papa like a comet and Mamma like the tail of one, to finish up the bridge that has kept them so busy for the last year.

This pension is kept by an American lady and is full of Americans. It is rather fun to be here for a while, but I am longing for the time to come when you will be with me and we can go apartment hunting, that is, if your mother still thinks it will be wiser for us to keep house and not try to board. Of course you will come here first and we can take our time about getting settled for the winter. Mrs. Pace, the landlady, (but you had better not call her that to her face, as she is very much the grande dame, with so much blue blood she finds it difficult to keep it to herself,) wants you to stay all winter with her and has many arguments against housekeeping, but I'll let her get them off herself to your mother.

She is looking forward with great interest to meeting dear Mrs. Brown, as it seems she knows intimately a cousin and old friend of hers, a certain Sally Bolling of Kentucky, who is now the Marquise d'Ochtè, a swell of the Faubourg St. Germain, with a chateau in Normandy, family ghost, devoted peasantry and what not. I fancy your mother has told you of her. It will be great fun to meet some of the nobility, I think.

I am enrolled at the Julien Academy for the winter and am going to put in some months of hard drawing before I jump into color. I work only in the morning and spend the afternoons looking at pictures. I am such a sober person pacing the long galleries of the Louvre studying the wonderful paintings that no one would dream I am the harum-scarum I really am. Papa gave me a very serious talking to about how to conduct myself in Paris and I find, as usual, his advice is excellent. His theory is that any grown woman can go anywhere she wants to alone in Paris, provided she has some business to attend to and attends to it.

Of course Mrs. Pace is merely a nominal chaperone for me until your mother comes. She really seldom sees me, and when she does she is so full of her own affairs that she hardly remembers I have any; and then when she recalls that she is supposed to be my chaperone, she feels called upon to tell me to do my hair differently, or she does not like my best hat, or something else equally out of her province. But I am not going to tell you any more about her, as you can judge for yourself when you see her.

I am sorry your brother, Kent, cannot carry out his plan of studying at the Beaux Arts, but maybe something will turn up and he can come after all. I might have known Aunt Clay would obstruct, all she had in her power, but thank goodness, her power is limited and your mother will finally get the full amount of money for her oil lands that Papa thought she should have. As for being in Paris without much money, it really is a grand place to be poor in; and one can have more fun here on a franc than in New York on a dollar.

Hug your darling mother for me, and tell Kent that I refuse to answer his letters unless he gets some thin paper to write on. I am tired of paying double extra postage on his bulky epistles.

Let me know in plenty of time when to expect you and your mother, so I can engage the room of Mrs. Pace and meet you at the station. I wish I could go to Antwerp to be there when you arrive or even meet you halfway in Brussels, but I must put the temptation from me and await you quietly in Paris. Good-by, my darling old Molly Brown,

Your own devoted, ever loving

Judy.

Steamer letter from Professor Edwin Green of Wellington College to Miss Molly Brown of Kentucky, sailing on S. S. Laurens.

Wellington College.

My dear Miss Molly:

Surely the "best laid schemes of mice and men gang aft aglee." I feel more like a mouse caught in a trap than a man, just now. I have been thinking of nothing else all summer but the delightful time I should have with you and your mother in Paris. It is my sabbatical year at Wellington, which means a fine long holiday, one much needed and looked forward to by all hard-worked professors. But just as I began to prepare for this delightful trip, I found that my substitute had in the most unaccountable manner, disappointed the President, Miss Walker, and Wellington was in a fair way to open without a professor of English. Of course I had to rush to the rescue and here I am in the old grind again.

I really do not mind teaching, enjoy it, in fact, but oh, my holiday and those walks and jaunts I have been dreaming of in Paris! Miss Walker is deeply grateful to me for helping her out of this difficulty, and is doing all in her power to find a suitable person to take my place; and of course, I, too, am reaching out in every direction for help.

One thing, I do not intend to be like poor Jacob: serve seven years more before I get my reward. I feel in a way that this is making up to the College for the long, enforced holiday two years ago, when I was so ill with typhoid fever.

My sister Grace had made her plans to spend the winter in New York as she did not expect to be needed by me as housekeeper, so I am "baching" again; and very lonesome it is after being so spoiled and looked after by Grace.

The place seems sad and gloomy to me and the College is full of raw and unattractive girls. I could hardly refrain from throwing a copy of Rosetti at a forward miss the other day in class, when she attempted to read "The Blessed Damozel" and I remembered a certain little Freshman, who, five years ago, held me enthralled by her rendering of that wonderful poem.

I was delighted to see your friend Miss Melissa Hathaway, who is a relief indeed, after all of these chattering school girls. What a wonderful personality she has! Her beauty is even richer and more glowing than formerly. She reminds me of October in the mountains, her own Kentucky mountains. Did you ever notice her eyes and the quality they possess, which is a very rare one: that of seeming to hold the reflection of trees and skies when she is indoors? It is as though she were still seeing her forests at home.

I hope to help her a great deal in her English as she is afraid this will have to be her last year at college. She feels that she is needed at home to carry on the work of her friend and teacher Miss Allfriend, whose long and arduous labors among the mountain folk have impaired her health. Melissa thinks she should take up the work and give her friend a rest. Noble girl! Dicky Blount thinks so, too, and even more so. Did you know that he found or manufactured some business in Catlettsburg, Kentucky, last summer and surprised Miss Hathaway in her mountain fastness?

Please give my kindest regards to your mother and express to her my deep regret that I am not to be her cicerone for some of the sights of Paris. I am hoping that before the winter is over I may be relieved and then, ho, for the fastest steamer afloat!

I am sending you some novels that may amuse you both on your voyage; also, a box of crystallized ginger that is the very best thing for seasickness that I know,—not that you are to be seasick, but just in case.

I am trying to be cheerful and not let Miss Walker see how I am kicking at fate, but I am as mad as a schoolboy who has to do chores on Saturday! Very sincerely your friend,

Edwin Green.

Mrs. Brown and her daughter Molly were at last safely off on what they called their "great adventure." They had waved their handkerchiefs until the dock at Hoboken was nothing more than a blur to them and they felt sure that the Laurens was little more than a speck to the friends that had turned up to see them off.

Molly's classmates at Wellington College, Katherine and Edith Williams, Edith with the nice, new husband whom Molly was overjoyed to meet, had appeared, bearing books and candy for the trip. Jimmy Lufton, of course, just to show that there was no hard feeling, as he whispered to Molly, was there, also, doing everything for their comfort; finding their luggage; engaging the steamer chairs; seeing to it that the stewardess understood about the baths before breakfast; and attending to many things of the importance of which Molly and her mother were ignorant.

Richard Blount, too, had turned up ten minutes before sailing, but he had managed to get in a word with Molly about Melissa Hathaway.

"She is a queen among women, Miss Molly, and I consider that Edwin Green is a lucky dog to have the privilege of teaching her. To think of seeing her day after day and hearing her read poetry with that wonderful voice! He tells me she is the most remarkable reader he has ever known. I am too fond of old Ed to hate him, otherwise I should find it easy. By the way I have left something in care of the steward for you and your mother as a cure for seasickness. You will find that there is nothing like it!"

"Oh, thank you so much! I feel sure that I shall not be sick, but I am just as obliged as though I were going to be. Mother may be. You see we have never been on the ocean in our lives, but we have always felt that we would like it beyond anything, and that liking it so much would keep us from being harmed by it," Molly had answered, a little chagrined at what Richard Blount had had to say about Professor Green and Melissa, but determined not to show it to that young man or to let herself think there was anything in it.

Miss Grace Green and dear, good Mary Stewart had been on the steamer waiting when Molly and her mother came aboard. Their devotion to Molly was so apparent that they won Mrs. Brown's heart at once, and that charming lady with her cordial manner and gracious bearing as usual made Molly's friends hers.

Miss Green had had a little private talk with Molly, giving her messages from her younger brother, Dodo, and telling her what she knew of Professor Edwin's disappointment in having to go on with his duties for the time being at least. Molly had not had a chance to open and read the steamer letter he had written her, but was forced to postpone it until the vessel sailed and she could compose herself after the flurry of good-bys and the bustle of the departure.

There were many letters waiting in the cabin, but the harbor was so fascinating to these two women who had done so little traveling, that they could not tear themselves from the deck until they were out of sight of land.

"Mother, isn't it too lovely and aren't we going to be the happiest pair on earth? I am glad we are seeing the ocean for the first time together, because you know exactly how I feel and I know how you feel. The idea of our being seasick! Richard Blount sent some remedy to the steamer for us, just in case we were seasick. It was very kind of him but absolutely unnecessary, I am sure. I never felt better in my life and look, there is quite a little swell."

"Seasick indeed! I have no more feeling of sickness than I have on the Ohio River at home," said Mrs. Brown, taking deep breaths of the bracing salt air. "I suspect it is incumbent upon us to go read our letters now, but I must say I do not want to miss one moment on deck during our entire voyage. I feel as though twenty years had dropped off me." And indeed she looked it, too, with a pretty pink in her cheeks and her wavy hair blown about her face.

Molly rather wanted to read Professor Green's letter first, but she put it aside and opened those from Nance Oldham and several other college mates. Then she discovered a thoroughly characteristic note from Aunt Clay, dry and dictatorial but enclosing a check for ten dollars on Monroe & Co., the Paris bankers. "For you and your extravagant mother to spend on foolishness," wrote that stern lady.

"Oh, Mother! Isn't she hateful? How easy it would have been to send a pleasant message with the check! Now all the fun of having it is gone and I have a great mind to send it back!"

"No, my dear, don't do that. Your Aunt Clay does not mean to be as unkind as she seems. I know she intended this check as a kind of peace offering to me, and we must take it as she meant it and pay no attention to her words."

"Mother, you are an angel and I have to hug you right here in the cabin, even if that black-eyed man over there with the pile of telegrams in front of him is looking a hole through us."

She suited the action to the word and Mrs. Brown, emerging from the bear hug that Molly was prone to give, surprised a smile on the dark face of their fellow traveler. He was seated across from them at the same table behind a pile of telegrams a foot high, and was very busy opening the messages, making notes on them as he read. He was an interesting looking man with dark, fathomless eyes, swarthy complexion and iron gray hair, but he bore a youthful look that made one feel he had not the right of years to the gray hair. His expression was gloomy and not altogether pleasant, but when he smiled he displayed a row of dazzling white teeth and his eyes lost the sad look and held the smile long after his mouth had closed with a determined click.

"'Duty before pleasure,' as King Richard said when he killed the old king before a-smothering of the babies," said Molly as she finished Aunt Clay's letter and opened Edwin Green's. What a nice letter it was to be sure! She laughed aloud over his wanting to throw Rosetti at the girl and blushed with pleasure at the compliment to her reading of the blessed Damozel, for well she knew whom he had in mind. His praise of Melissa would have merely pleased her as praise of her friends always did, had she not already been somewhat disturbed by what Dicky Blount had said to her of Professor Edwin Green and the beautiful mountain girl.

"I am a silly girl and intend to put all such foolish notions out of my head," declared Molly to herself. "Surely Professor Green has as much right to make friends as I have, and I intend to know as many people and like as many as I can. I am not the least bit in love with Edwin Green,—but somehow I don't think he and Melissa are suited to one another."

As the young girl sat reading over her letter, a feeling of sadness and loneliness took possession of her and, looking up, she surprised a furtive tear in her mother's eye. Mrs. Brown was reading a letter from her married daughter Mildred, then living in Iowa where her husband Crittenden Rutledge was at work as a bridge engineer.

The cabin had begun to fill with people who were leaving decks and staterooms to hunt up their letters and belongings and generally prepare themselves for a ten-day trip on the Atlantic.

"Mother, they say this is a small steamer, but it seems huge to me! Did you ever see so many strange people? I don't believe we ever shall know any of them. They all of them look at home and I feel so far from home. Don't you?"

"Now, Molly, please don't get blue or I shall have to weep outright. Of course we shall come to know most of the passengers and no doubt will find many charming persons ready to know and like us. Suppose we hurry up with our letters and go on deck again."

Just then a young man bounded into the cabin, made a hasty survey of the crowd and came rapidly over to the dark gentleman seated opposite them.

"Oh, Uncle Tom, how can you stay down in this stuffy cabin? There is a sunset on the water that is just screaming out to be looked at. As for that work, you have ten days to attend to those tiresome telegrams and letters."

"Nonsense, Pierce, I have no idea of waiting ten days for this important business. You forget the wireless," answered the uncle, looking fondly at the enthusiastic young fellow, who was so like him except for the gray hair that it was almost ludicrous.

"Oh, goodness gracious me, where is your holiday to be, with you tied to your Mother Country with a stringless apron? That is what that old wireless telegraphy reminds me of," laughed the young man, showing all his perfect teeth. "Well, I've got your chair and steamer rug all ready for you and all you have to do is come sit in it."

"Now, Pierce, don't wait on me. Part of having a holiday is to forget how old I am. When I get these telegrams off, I am going to show you how skittish I can be and forget all about business. I fancy you will have to hold me back in my race for a good time. This limerick is to be my motto:

Mrs. Brown and Molly could not help overhearing this conversation and at the above limerick they laughed outright. The young man called Pierce looked at them with a friendly glance and the uncle smiled another of his rare smiles, which made the ladies from Kentucky feel that the ocean was not going to be such a terribly lonesome place after all. They gathered up their belongings and made their way on deck to view the sunset that was "screaming to be looked at."

"It really is worth seeing, isn't it, Mother? Somehow, though, I never do like to be made to look at a sunset. The persons who insist on your doing it always seem to have a kind of proprietary air. Now that young man wanted to bulldoze his uncle into coming when—when——" Molly stopped suddenly, realizing that the two men in great-coats, with the collars turned up to their ears, who had taken their places at the railing next to her mother, were no other than the two in question.

"You are perfectly right, madam," said the elder, raising his hat. "This nephew of mine is always doing it. Now I should much rather come on deck when the sun is down and see the after-glow. The crepuscule appeals to me more than the brilliancy of the sunset."

"I fancy my daughter had no complaint to make of the brilliancy of the color, but of being coerced into looking at it. She likes to be the discoverer herself and the one to make others come to look. Isn't it so, Molly?"

"Maybe it is," said Molly blushing. "I did not really mean much of anything and was just talking for talk's sake."

"Anyhow," spoke the nephew, "this sunset is mine and I think it is beautiful and all of you have simply got to look at it." Turning to Molly, "You can have to-morrow's and make us look all you want to, but this is my discovery."

The ice was broken and Molly and her mother made their first acquaintances on their travels. Mr. Kinsella introduced himself and his nephew Pierce and in the course of half an hour they were all good steamer friends. Everyone must make up his or her mind to be ready to make friends on a steamer or to have a very stupid, lonesome crossing. Mrs. Brown and Molly were both too sociable and friendly to be guilty of such standoffishness and were as pleased at making friends with the two Kinsellas as those gentlemen were to secure such pleasant companions as these ladies were proving themselves to be.

"We are all of us to be at the captain's table," said Pierce.

"And how do you know where we are to be?" asked Molly. "I don't know myself where we are to sit, and how can you know?"

"Oh, that is easy. While you and your mother and Uncle Tom were busy reading your letters and before I got my sunset ready, I was finding out things like Rikki-tikki. First I got the steward's list and located the Kinsellas at mess; then I looked over all the names and where the people hailed from and decided that Miss Molly Brown of Kentucky sounded kind of cheerful. And when I knew there was a Mrs. Brown along, too, I decided that Miss Molly Brown was young enough to have a mother along and the mother was young enough to be along, and you were more than likely a pretty nice couple to cultivate. The steward told me you were to be at the captain's table, too, as you were friends of Miss Mary Stewart. Her father owns much stock in these nice old tubs of steamers, and the daughter had made a special request that you should be very well looked after."

"Isn't that too like Mary? She did not say one word about it. That accounts for our having such a lovely stateroom to ourselves, too. We had engaged a stateroom that was supposed to hold three persons. The company had the privilege of putting someone else in with us, and as the steamer is quite full, of course we had expected to have a roommate. We hated the thought of it, too, but it was so much less expensive. And Mother and I hoped to spend most of our time on deck, anyhow. We could not understand the number not being the same as that on our tickets, but thought the officials knew best and if we did not belong there they would oust us in good time."

"Well, I am jolly glad you have the best stateroom on board. Uncle tried to get it but had to content himself with second best."

"Are you seasick, as a rule? I do hope not," asked the young man of Mrs. Brown, who had been conversing with Mr. Kinsella while the nephew and Molly were making friends.

"No, we don't make it a rule to be any kind of sick; but my daughter and I are on the ocean for the first time. In fact, we are really seeing the ocean for the first time and do not know how we are to behave. So far we feel as well as possible, but I fancy such a smooth sea is no test."

"Only fancy, Uncle Tom, what it must seem to see the ocean for the first time! I almost wish I had never seen it until now, just for the sensation."

"There was a superior New York girl at Wellington College who had a great time trying to tease me because I had never seen the ocean. She kept it up so long that I began to feel like a 'po' nigger at a frolic', so I retaliated by asking her if she had ever been to a hanging. I completely took the wind out of her sails, and then confessed that I hadn't either," said Molly with a laugh.

"Good for you, Miss Brown, give it to him. New York people are certainly very superior in their own estimation and need a good taking down every now and then. They are often more provincial than villagers, with no excuse for so being," and Mr. Kinsella gave his nephew an affectionate push.

The air was clear and crisp, with a rising wind that gave promise of a heavy sea. The passengers had begun to fill the decks, dragging steamer chairs into sheltered nooks and looking about for desirable places out of the wind, where they could see the sun set and the moon rise, get out of the way of the smokestacks, the fog horn and the whistle, and at the same time be in a good locality to see everything that was going on. Molly and her mother were much amused at the sight. They were both inclined to be rather careless of their ease and it had never entered their heads to hustle and bustle to make themselves comfortable on the trip.

"Jimmy Lufton has had our chairs placed on deck and lashed to the railing. He said he knew we would never look out for ourselves, and unless he saw to it, we would go abroad standing up or sitting on the floor! He tagged our chairs, too, as our names were on the backs only. He said there were always some 'chair hogs' who would push the chairs against the wall with the name out of sight and refuse to budge," said Molly.

"Where are your chairs?" asked Pierce. "Let's go find them and afterward we can get Uncle's and mine and have a snug foursome of a chat. Oh, Miss Brown, how lovely your mother is! I want to paint her; but I should have to put you in the picture, too, so that I could catch the wonderful expression on her face. It is when she is looking at you that she is most lovely."

"Well, don't you think I could be present to inspire the desired expression without being in the picture?" laughed Molly, delighted by the praise of her beloved mother. "But can you paint? I have been wondering what you are and what your uncle is, but I did not like to be too inquisitive."

"Well, one does not have to be with me long to hear the story of my life," said the boy. "You ask if I can paint: yes, I can paint; not as well as I want to by a long shot, but I mean to be a great painter. That sounds conceited, but it is not. I have talent and there is no use in being mealy-mouthed over it. To be a great painter means work, work, work; and I am prepared to do that with every breath I breathe. Painting isn't work to me; it is joy and life. Besides, I mean to make it up to Uncle for his disappointment in life, and the only way I can do it is by succeeding."

Molly was dying to know more about the uncle and what his disappointment was, but she was too well bred to show her desire and Pierce did not seem inclined to go on with his family disclosures. He stood looking at two ladies who had just come on deck, followed by a maid carrying rugs and cushions. The ladies were a very handsome mother and daughter, although the mother appeared too young to have such a very sophisticated, grown-up daughter. They were beautifully dressed in long fur coats and small toques. "Rather warm for October," thought Molly, but the rising cold wind soon made her know her mistake.

"There are our chairs," said Molly, starting toward the railing where the ever handy-man, Jimmy, had lashed the two steamer chairs.

At the same moment the elegant, fur-clad lady rapidly crossed the deck and placing her hand on the back of the nearest chair, said in a cold and haughty tone to the maid: "Here, Marie, place the rugs and cushions in these chairs. They will do quite nicely."

"Excuse me, but these chairs are ours, mine and my mother's," said Molly. "But we are not going to use them until after supper, I mean dinner, so you are welcome to them until then."

"Some mistake surely," rejoined the older woman, eying Molly scornfully through her lorgnette. "You will have to complain to the steward if you cannot find your chairs, young woman; these are mine, engaged and paid for." With that, she prepared to seat herself with the help of the maid, who was blushing furiously, mortified by the flagrant untruth of her mistress.

Molly was, by nature, easy-going and peace-loving and her inclination was to leave the haughty dame in possession of the chairs and beat a hasty retreat; but she remembered Jimmy Lufton's remark about "chair hogs" and a joking promise she had made him to stand up for her mother if not for herself, so she braced herself for battle. Despite her girlish face and figure, Molly Brown could command as much dignity as any member of the Four Hundred.

With a polite smile and gently modulated voice she said, very calmly and firmly: "Madam, as I said before, these are my chairs but you are quite welcome to them until after dinner. If you have any doubt about it, you will find our names on the backs; but to save you the trouble of moving to look behind you, if you will be so kind as to glance at these tags you can verify my statement."

"Oh, I did not dream I was to call forth such a tirade," yawned the nonplussed woman, reading the tags: "'Mrs. M. Brown, Kentucky; Miss M. Brown, Kentucky.' If you are not going to use the chairs until after dinner, my daughter and I will just stay in them until other arrangements can be made. These small steamers are wretchedly managed. I can't imagine where our chairs are. Elise," calling to her daughter, "it seems these are not our chairs, after all."

"Well, I did not think they could be, as these chairs seem real enough and ours are entirely imaginary," answered the daughter rudely. "Mother, this is Mr. Kinsella, whom I have known at the Art Students' League. My mother, Mrs. Huntington, Mr. Kinsella."

"I am so glad to meet you, Mrs. Huntington. Your daughter, Miss O'Brien, and I have been working in the same costume class at the League. I did not dream she was to be on this boat and when I saw her come on deck I thought I was seeing ghosts."

Pierce had come eagerly forward to meet the mother of the interesting girl he had known and liked at the art school; but Mrs. Huntington looked as though she, too, were seeing ghosts. She shrank back in her down pillows and her face became pinched and pale, and it was a moment before the hardened woman of the world could command her voice to return the greeting of the young man.

"Kinsella, did you say? Could you be Tom Kinsella's son? You are strangely like him."

"Thank you, madam, for that. There is no one I want to be like so much as my Uncle Tom. I am his nephew; my uncle has never married. Did you know my uncle? He is on board and I know would be glad to renew his acquaintance with you. But let me introduce Miss Brown to both of you."

The two girls shook hands, and as they looked in each other's eyes, Molly felt in her heart an instinctive liking for the older girl. There was something honest and straight about her face despite the rather sullen expression of her mouth. She was beautiful, besides, and beauty always appealed to Molly,—almost always, at least, for although Mrs. Huntington was beautiful, too, Molly felt no leaning toward her. Mother and daughter looked enough alike to make it not difficult to guess the relationship at the first glance; but the more one saw of them, the fainter grew the resemblance. The older woman was smaller, fairer and plumper; her hair was golden while the daughter's was light brown; her complexion pink and white, the daughter's rather sallow; her eyes baby blue, the other's gray green. But the daughter's features were more pronounced and her well-cut chin and mouth showed character and pride, while the mother's looked a little petulant.

"I am very glad to meet you, Miss Brown. I believe I have heard of you. Aren't you Julia Kean's 'Molly'?" And Elise O'Brien gave Molly's hand a little squeeze.

"Of course I am. To think of your knowing my Judy! You must have met her at the League. Perhaps you knew her, too, Mr. Kinsella."

"Who? Miss Kean? I should say I did. She was the life of the outdoor sketch club we got up; and believe me, she has a soul for color. Why, that little 'postage stamp landscape' she had in the American Artists' Exhibition was a winner. Did you see a memory sketch she did for the final exhibition at the League? It was a tall girl in black standing up singing and a beautiful red-headed girl in diaphanous blue playing an accompaniment on a guitar, with a background of holly and a great bunch of mistletoe at one side." Pierce stopped suddenly in the midst of his description of Judy's picture and, gazing intently at Molly, cried out, "By the great jumping jingo, if Miss Brown isn't the red-headed girl in diaphanous blue!"

"Yes, I saw it," exclaimed Elise, "and thought it was wonderfully clever. Miss Kean got a splendid likeness of you, considering it was from memory."

"Oh, Judy has sketched me until she says doing me is almost as easy as writing her name. That must have been the Christmas party at Professor Green's when Melissa Hathaway was singing 'The Mistletoe Bough.' I remember Judy sat opposite us and I almost laughed out because she kept making pictures in the air with her thumb, which is a habit of hers when anything appeals to her as paintable. Won't it be splendid to see her again? Are you both going to Paris? You know Judy is there now and my mother and I are to join her."

"Glorious!" exclaimed the enthusiastic Pierce. "Of course I am going there; but how about you, Miss O'Brien?"

"Oh, I am to be there for a while, but my art is not considered seriously enough for me to stick at it long enough to accomplish much. Mother thinks Paris is nothing but one big shop, and when she has bought all the clothes we are supposed not to be able to be decent without, we have to go on. I am going to work while she shops. Thank goodness, she is so fussy that it takes her twice as long to get an outfit as it would anyone else, so I shall have time to get in some work," answered the girl bitterly.

Just then the gong was sounded for dinner. There was a general movement toward the saloon and the growing darkness prevented Molly from seeing the resentment on the face of Mrs. Huntington, if resentment she held, at the daughter's rudeness toward her.

"Such a nice girl," thought Molly, "and so clever and beautiful! But how, how can she be so horrid to her mother? There is no telling what provocation she has, though. Her mother was certainly not honest about the chairs; but then, your mother is your mother. Thank goodness, Aunt Clay is not mine!"

Molly hastened to her own mother's side and they made their way to the first meal on board.

Such a pleasant bustle, as the passengers came streaming into the cabin! Everyone seemed to have made or met some friend, with the exception of a few shy-looking, lonesome persons, and Molly devoutly hoped that these would find some congenial souls before very long and not be so forlorn. She and her mother had made such a fine beginning in the way of pleasant acquaintances that she wished the same good luck to all on board.

Their seats were next to the Captain, with Mr. Kinsella and Pierce opposite. The Captain was just what a captain ought to be: big and hearty, blond and bearded, with a booming laugh. "Like a Viking of old," whispered Molly to her mother.

"Good sailor, madam?" asked the Captain of Mrs. Brown.

"A Mississippi steamboat is the only test I have given myself so far, but my daughter and I are hoping we will prove good sailors," answered his neighbor. "We are evidently expected to be sick by our friends, as several of them have sent us remedies. Champagne from one, crystallized ginger from another and a box of big black pills from a third that look for all the world like shoe buttons."

"Well, don't trust to any of them. If you are sick, get on deck all you can and don't waste your champagne on seasickness, but get ginger ale, which is much cheaper and quite as effective," boomed the Captain with a laugh that made the glasses rattle.

Molly wished they would stop talking about seasickness! The food looked good. A plate of cream celery soup had just been placed in front of her. It seemed all that celery soup should be, but a qualm had suddenly arisen in her soul, (at least she called it her soul,) and she decided to let the soup go and wait for the next course.

"Uncle Tom, I have met an old friend of yours on board; also an acquaintance of my own from the Art Students' League," said Pierce as soon as the business of eating was well under way.

"Is that so? I'll bet on you for nosing around to find out things! Who is the gentleman?" inquired Mr. Kinsella.

"Gentleman much! It's a lady, and a very beautiful lady at that, who complimented you greatly by saying you looked like me," laughed the boy. "Her name is Mrs. Huntington."

"Huntington? I know no one of that name that I can remember. She must be some casual acquaintance who has slipped from my memory."

"Well, maybe,—anyhow, she called you Tom. Her daughter, Miss Elise O'Brien, is my friend."

Mr. Kinsella's face flushed and his somber eyes lit up with what Molly thought an angry light.

"So," he muttered, "she has married again. Yes, yes, my boy, I—I did know a Miss Lizzie Peck in my youth who married an old friend of mine, George O'Brien. I have not seen or heard of them for years and did not know George was dead. I shall take great pleasure in meeting his little girl."

"Little! She is as tall as Miss Brown, who is certainly not stumpy, and is some years older, if I am any judge of the fair sex."

"Of course you are a judge of the fair sex, a most competent one, I should say. What boy of eighteen is not?" teased his uncle. "Where are your new acquaintances seated?"

"They are at the other end of the next table with their backs to us. You will have to rubber a little to get a good view of them."

Mr. Kinsella accordingly "rubbered," as his slangy nephew put it, and satisfied himself of the identity of Mrs. Huntington. Molly was greatly interested in the occurrence. Mr. Kinsella was different from anyone she had ever seen before and Pierce's hint of a disappointed life had fired her imagination, ever ready for a romance. She had a feeling that the proud, beautiful, inconsiderate woman whose acquaintance she had recently made was in some way connected with Mr. Kinsella's disappointment.

Soup was removed and the next course of baked bluefish brought on. Molly's senses reeled and a drowsy numbness stole over her. "What a strange feeling! What on earth is the matter with me? I was so hungry when I came down here and now I can't touch a thing," she said to herself.

Mr. Kinsella was watching her and finally spoke:

"My dear Miss Brown, let me take you on deck. You will feel much better in the air."

"Why, my darling daughter, are you sick?" inquired the anxious mother, who was eating her dinner with the greatest enjoyment.

"I believe I'll go to bed," gasped poor Molly. "But don't you come, Mother. I'll be better in a minute."

A grim smile went down the Captain's table as Molly beat a hasty and ignominious retreat. Mrs. Huntington was heard to remark to her daughter as a white and hollow-eyed Molly flew past their chairs on the way to her stateroom: "There goes that red-headed girl from Kentucky, who was so rude to me on deck. I fancy we can occupy her chairs for a while longer."

"Oh, Mamma, why do we not have chairs of our own? It is so embarrassing to sponge on other people all the time, and the expense of chairs is not very great," implored Elise.

"Nonsense, Elise; I have crossed the ocean innumerable times and never get chairs. There are always enough seasick people who have to stay in their bunks, and since I abhor waste, I use their chairs. As you say, the expense is not very great, but if I do not save in small ways I cannot make ends meet and keep up appearances and that is most important, until you see fit to catch a husband."

All this was in an aside to her daughter, who seemed accustomed to such remarks and coolly helped herself to stuffed mangoes without deigning any reply. But after brooding a few seconds she spoke:

"Do you think that the chair episode on deck before dinner was 'keeping up appearances' very well?"

"And so you have your eye on young Mr. Kinsella, have you?"

"Not at all, Mamma, and you know I haven't. In the first place, Pierce Kinsella is years younger than I am, and while he is tremendously clever with his brush, he is not the intellectual man I must have or do without."

"Never mind your age. If you do not mind being frank on the subject, you must have some consideration for me, who am your unwilling mother. No one will ever believe I was a mere school girl when I married George O'Brien. If I should not keep up appearances for young Kinsella, who was it, please? Surely not that Miss Smith!"

"Miss Brown, Mamma, Molly Brown. She is a lovely girl and a perfect lady; and what will have more weight with you, she is a friend of the Stewarts. Pierce Kinsella told me it was at Mr. Stewart's request that she and her mother were put next to the Captain and they have the best stateroom the ship affords."

"Ah, dead-heads, I surmise."

"Not at all. They had their tickets and stateroom engaged and did not know of the honor done them until Pierce Kinsella told them himself. I fancy we are the only dead-heads on board."

"Elise, I will not have you be so cynical. Mr. Stewart is a connection of mine and I am entitled to some consideration from him," snapped the mother.

"Yes, I know, a very close connection: Mr. Huntington's first wife's cousin-in-law. For that reason, you must have transportation free on a line of steamers Mr. Stewart is interested in; but you had to send me to ask for the favor, and I'll tell you now what I did not tell you before for fear of hurting your feelings, that Mr. Stewart said he was glad to do it for my sake."

The last was a poser for the angry woman, and mother and daughter ceased their wrangling and devoted themselves to the very good dinner.

Poor Molly got to bed as best she could and stayed there twenty-four hours. She was sure her seasickness was the worst that had ever been known, but we all feel that. On the second day she was persuaded to go on deck by her solicitous mother,—who, by the way, was not uncomfortable one minute,—and as she dropped limply into her steamer chair, carefully arranged for her by the Kinsellas, she for the first time had a desire to live. The ocean was a wonderful color, all pearly gray with little flecks of pink on top of every wave. The sun was setting in a mist. The wind had died down and there was a delicious dampness in the air that smelt of salt.

"Oh, how glad I am to get up here! All of you are so good to me. It seems a year since I went to my stateroom and I believe it is only a day and a night. Has anything happened since I disappeared?"

"Nothing," answered Pierce. "The sun and the ship have moved but the rest of us have just stood still waiting for you to come back. By the way, this is your sunset, you remember. You forgot to advertise it, so you have not a very large audience."

"Well, if Miss Brown can get up that good a show without even trying, what couldn't she accomplish if she put her mind on it? I believe I like yours better than Pierce's," said Mr. Kinsella. "His was so flamboyant, while yours has a certain reserve and distinction."

The conversation went gayly on between uncle and nephew while Mrs. Brown hovered over her daughter, tucking in the rug and shifting the pillows for more perfect comfort. Molly smiled a little wanly at first but soon the good air and gay talk got in their perfect work, and before she knew it she was laughing outright at some of Pierce's sallies. The color began to come back into her cheeks. A desire for life grew stronger and stronger. Mr. Kinsella noticed the change in the girl, and while Mrs. Brown and Pierce were engaged in an animated discussion on Woman's Suffrage, Pierce taking the Anti side "just for practice," he slipped away and soon returned with a tray of dainty food.

"Please eat a little something now, Miss Brown. It will put new life in you and I feel sure you are on the mend and can trust yourself to take some nourishment. Chicken aspic and dry toast can't hurt you, and I feel sure it will do you good."

"Why, Mr. Kinsella, you are too good to me! How did you know I was hungry? I was ashamed to say so, but I felt that a little food was all that was needed to make me perfectly well." And Molly fell to with an avidity that surprised her mother, who had not been able to persuade her to take a mouthful all day.

"I have seen seasick persons before now," laughed Mr. Kinsella, "and know by experience that there is a crucial moment when food must be administered, and then the patient gets well immediately. I noticed you were laughing, and no one with mal-de-mer can laugh! And then your color came back, and that is a signal for food, too. I am so glad you like what I brought you."

"Mr. Kinsella, I cannot tell you how grateful I am," said Mrs. Brown. "I don't wish you to be seasick, but I do wish Molly and I could repay your kindness in some way."

"My dear lady, I am already in your debt for permitting my scape-grace nephew and me to know you and your daughter. I have had my nose at the grindstone of business for so many years that I feared it had grown out of my power to make new friends; but I begin to see that I have not lost the knack. Perhaps my somber presence is tolerated because of my gay, jolly boy," and Mr. Kinsella gazed rather wistfully after Pierce, who had crossed the deck to meet Elise O'Brien, just emerging from the cabin.

"Oh, Mr. Kinsella, you must not think that," eagerly implored Molly. "I always like serious men better than boys, and besides you are not somber but full of gaiety and jokes. You are not fair to yourself if you think people like you only on account of Pierce. He is a delightful boy, but——"

"But what?"

"Don't press her too far, Mr. Kinsella," laughed Mrs. Brown. "She has already confessed to a penchant to seriousness and finds 'beauty in extreme old age'," and pinching Molly's blushing cheek, she went over to join a group of recently made acquaintances who were looking at a distant sail through an overworked spyglass belonging to one of the tourists.

"What a tease Mother is! But she looks so like my brother Kent when she teases me that I don't mind. Kent is always teasing and the only reason I can stand it is that it makes him look like Mother! You see, Kent is my special beloved brother and you know what my mother is."

"Yes, I know," answered Mr. Kinsella, who had sunk into the chair vacated by Mrs. Brown. "Your mother is a rare woman: beautiful and honest and tolerant, charming and well-bred, broad-minded and cultured. Eternal youth is in her heart, but she has a character gracefully to accept the years that Providence has allotted her and that only serve to make her more lovely. I have no patience with the assumption of extreme youth in the middle-aged, despite the limerick I have taken for my motto."

"But, Mr. Kinsella, you are not middle-aged," protested Molly. "I never even think of Mother as being middle-aged. I think that is the ugliest word in our language, except, maybe, stout. I'd a great deal rather be called fat and forty than stout and middle-aged!"

"Well, it will be many a year before you will be called either, and by that time you may change your mind. 'A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,' and, after all, it is being stout and middle-aged that makes the difference, not being called it."

While Molly was having the little chat with Mr. Kinsella, Mrs. Huntington had come on deck and had approached them from behind. Looking up, Molly surprised on her face an expression of extreme bitterness, and she wondered if she had overheard Mr. Kinsella's views on the subject of the assumption of youth in the middle-aged. "I do hope she didn't," thought Molly. "She is so pretty, and it must be hard to give up youth and to feel your beauty slipping from you. Especially hard when beauty has been your chief asset in life, as I fancy it has been with Mrs. Huntington." She gave the older woman a polite bow and smile and Mr. Kinsella formally offered her his chair but with no great cordiality.

"Oh, thank you, Tom. And how are you, Miss Brown? I do hope you are feeling better. My daughter has taken such a fancy to you, she has been quite désolé at your nonappearance all day."

"Oh, I am all well again, thanks to Mr. Kinsella's getting me some food at the psychological moment when health was returning," answered Molly, wondering at Mrs. Huntington's change of tactics since the evening before, when she had been so insolent in her bearing to her. "It is certainly nicer to have her polite to me than rude, whether she means it or not," she said to herself. "I do wish I had not been sick all day. I did want to see her first meeting with Mr. Kinsella. I know she had something to do with his premature grayness and the disappointment that Pierce hinted at. How coldly polite he is to her now. If a man like that had ever loved me and then could be so cold to me, I believe it would kill me," which shows that Molly was very sentimental and on the lookout for romance.

The gong rang for dinner and there was a general move toward the cabin.

"Please tell Mother I am all right and will sit here while she is at dinner, and that she must not hurry. I believe 'discretion would be the better part of valor' for me and I had better not try to eat anything more for a while."

After the deck was clear except for a few helplessly, hopelessly sick persons who lay like mummies in their chairs, ranged along the deck, Molly decided to get up and walk around a little, feeling anxious to try her sea legs. Then as the wind had shifted, she determined to move her chair to a sheltered nook behind one of the life-boats. She bundled herself up in her rug, pulling the corner of it over her head and lay for all the world like the rest of the mummies. "Only, thank goodness, I am no longer sick," she thought gratefully.

Her soul was at peace, after the night and day of agony, and she dropped off easily into a doze. She dreamed that she was at home in the old apple tree that they had called "The Castle" and that Kent was gently shaking the tree, trying to make her get out so Professor Green could build his bungalow there; and when she refused and declared it was her Castle and she intended to stay in it, the Professor himself had come, with his kind brown eyes looking into hers, and said: "But, Miss Molly, the bungalow is yours, too, and the Orchard is still your home." She awoke but lay quite still wondering at the reality of her dream.

It had grown quite dark. The passengers were evidently still at dinner. A man loomed up close to her and then stopped, evidently unaware of her presence. Leaning over the rail and gazing into the black depths of water, he emitted a sigh that seemed to come from his soul. Suddenly a woman joined him. Molly was still half asleep, thinking of the orchard at Chatsworth and of what Professor Green's bungalow would look like among the apple trees. Her thoughts came back to the ship with a bounce when she heard the woman say:

"Tom, why do you avoid me? Can't you let bygones be bygones?"

"That is exactly what I am doing, Mrs. Huntington: letting bygones be bygones. It seems a useless thing for us to rake up the past."

"'Mrs. Huntington' sounds very cold and formal coming from your lips."

"Well, I gathered you did not think much of the name of Lizzie since you have changed your daughter's to Elise."

"Oh, Tom, you are cruel!"

"Now see here, Mrs. Huntington, I do not want to be rude to you. I have lived in total ignorance of you and your affairs for twenty-five years, and since by chance we meet on a steamer, you cannot make me feel that what I do or say is of the slightest importance to you. You made the young Tom Kinsella about as miserable as a man could be, but the old Tom is immune from misery, thank God, and there is no use in trying to get a flame from the dead ashes of the past. I am very glad to see you again and especially glad to make the acquaintance of the daughter of my old friend, George O'Brien."

"You forgive George but do not forgive me."

"I have nothing to forgive George, and you know it. He was the soul of honor and had no idea of there being an engagement between us, when he married you. I am as sure of this as though George himself had told me. In those good old days in Paris when we were all of us art students, George and I were great chums. I could read him like a book and there never lived a more honest fellow.

"When my father died and his foundry at Newark seemed in a fair way to be on its last legs for want of management and the family income was in danger of being decidedly lessened, you persuaded me, in fact, you put it up to me, to give you up or give up art and go to work and pull the foundry out of the hole.

"Art meant a lot to me, but at the time you meant a lot more. You remember you would not let me announce our engagement to our friends, not even to George.

"I went back to America and piled into a work, entirely uncongenial, but determined to win out. Things were in an awful mess because of my father's long inability to attend to business. My brother Pierce was still in college and could be of no assistance to me. I had to master the business from the beginning, learning every detail before I could put it on the efficiency basis that I knew it must attain before I could be satisfied.

"I wrote you rather discouraged letters, I will admit, but I felt I could pour out my soul to you and you alone. I knew it would be two or three years before it would be expedient for us to marry, but my faith in you was supreme and it never entered my head you would not wait for me.

"When the goal was in sight, you may imagine the shock it gave me when a casual acquaintance, recently returned from Paris, spoke of having had such a gay time at your wedding breakfast, given in old George's studio (the one I used to share with him) by his fellow students.

"Not a word from you; later on a letter from George, full of happiness and your charms and explaining to me how it came about he could marry. He had been one of the poorest among a lot of fellows, where poverty was the rule and not the exception; but his uncle, the Brooklyn politician, had died and left him a hundred thousand dollars. That seemed immense wealth to the Latin Quarter, and there was rejoicing in all of the atéliers where George O'Brien was a general favorite and Lizzie Peck was known as the prettiest American girl in the Quarter.

"The shock was so great I was like a dead man for weeks, but I never told a soul of my pitiful love affair. I got over the loss of you as soon as I could pull myself together enough to think that if you were the kind who could do as you did, I was well out of it; and George had my pity and not my envy. But my Art—my Art—nothing can ever make up to me for giving it up. I could not go back to it, as I had plunged too deeply into the foundry affairs to pull out, and one cannot serve business and Art at the same time. Art is too jealous a mistress to share her lover's time with anything else. I went on with the work and came out very well.

"This is the first real holiday I have had for many years, but I am determined to have a good time and am not going to let regret prey upon me."

Molly had been a forced listener to this long speech, but she could not fool herself into thinking she had been an unwilling one. She was thrilled to the soul by Mr. Kinsella's history. No wonder he was so sad looking and occasionally so bitter! She was glad he had not truckled to the spoiled Mrs. Huntington, but had let her know exactly where he stood. It was not so very chivalrous of him, but she needed a good mental and moral slap and Mr. Kinsella had administered it as gently as possible, no doubt.

What was Molly to do now? To let them know she was there would make it horribly embarrassing for all concerned, and still she felt she had already heard more than she had any business to know.

"I'll have to pretend I am asleep and never divulge to a soul, (except Mother, of course,) that I have overheard this tremendously interesting conversation."

Mrs. Huntington was silenced for a few moments by Mr. Kinsella's harangue, but finally spoke:

"Tom, you are hard on me. I was very young at the time and had always been so poor."

"That is so, Lizzie. It was hard on you to be so poor; but you were not so very young. You must have been about the age your daughter is now, and I fancy you would not excuse much in her because of her youth. You were two years older than I was in those days."

"Brute!"

"Mind you, I said 'in those days.' I do not mean you are still two years older than I am."

Molly was sorry that Mr. Kinsella was pushing the poor lady so far. She made a quick calculation from the evidence in hand and realized that Mrs. Huntington must be about forty-nine. "Almost as old as Mother! And just look at her hair and clothes! She looks much younger, and I know it is hard on her to give up her youth. I do wish Mr. Kinsella had not said that to her about being two years older than he is! It was not very kind, even if she did jilt him. It seems a small revenge to me. I wish I could have made my presence known and then I should not have heard Mr. Kinsella belittle himself, which I certainly think he did."

Poor Mrs. Huntington swallowed her resentment as best she could and continued the conversation: "There is one thing I should like to ask of you as a favor, Tom, and that is: please do not tell Elise that her father and I ever studied art. Not that I ever studied very hard, but George was certainly much interested and it took a deal of managing to persuade him to give it up and go into politics. You see, his uncle's influence was still hot and there were many plums waiting for him. I was too ignorant in those days to know that it did not necessarily follow that political jobs brought social success.

"George was very successful and doubled his inheritance, but we had no position at all. He changed a great deal. You would hardly have known him in his last years. You remember how gay and light-hearted and good-tempered he always was. Well, he lost it all and became morose and bitter. Elise was the only person who had any influence on him at all. We had to live in Brooklyn and how I did hate it!"

"How long has George been dead?"

"Oh, ten years or so. Elise was a mere child and George never spoke to her of having wished to become an artist. It seemed best to me for her to live in ignorance of the fact as she is already ridiculously fond of trying to paint; and if she knew there were any hereditary reasons for it, there is no telling what stand she would take. I hate the Bohemian life that artists lead, and now that I have made so many sacrifices for her to place her in the best society, I have no idea of allowing her to drop out.

"We are received in the most exclusive houses in New York and Newport, and while our means do not permit us to entertain very largely, our at-homes are most popular with the Four Hundred.

"Elise is very stubborn. She has had several excellent offers but refuses to consider anyone whom she does not love. George O'Brien was very sentimental and she has inherited that from him, along with her love for dabbling."

Mr. Kinsella had maintained a grim silence during this heartless speech; but he now asked: "What sacrifice have you made for your daughter's welfare, you poor put-upon lady?"

"Why, I married Ponsonby Huntington! He had not a sou to his name but he had the entrée into all the fashionable homes in the East. He was a great expense, but it fully repaid me, as he lived long enough to establish Elise and me in that society for which we are eminently fitted. I am deeply grateful to him and his family and do not begrudge the money, now that he is dead.

"I was keen enough not to let him go into my principal very largely. I am an excellent business woman, Tom, and have managed my affairs wonderfully well."

"So it seems," muttered Mr. Kinsella. "You have evidently satisfied all your ideals. I am glad to tell you that I have already divulged to Elise that her father might have become a very good painter, and was astonished that she was ignorant of the fact that he had ever drawn a line in his life. I say that I am glad, as I want to talk to George's daughter about her father, and I cannot think of my old friend, George O'Brien, as anything but the gay, care-free art student, always ready to go on a lark and to share his last penny, of which he had very few, with any needy fellow-student. Don't you ever feel like painting yourself?"

"No! I hate the sight of a paint brush, and as for adding in any way to the ever-increasing flood of poorly painted pictures,—I can at least claim my innocence of that crime."

"Perhaps you are right, but you used to be so clever at catching a likeness."

"Elise has the same power, but I hate to see it in her and never encourage her by the least praise. Of course you can't understand this feeling, but I know the girl would fly off at the slightest chance and live in that shabby Latin Quarter. There, no doubt, she would marry some down-at-the-heel artist, who would live on her money and go on painting bad pictures to the end of time; and she would aid and abet him and paint worse ones herself!"

"Elise has money, then?"

"The money is all hers except my pitiful third that the law allows me, and I had to go into that a little to keep Ponsonby Huntington in a good humor. However, Elise cannot get control of her money until she is twenty-five and I have several years yet. She is quite equal to throwing me over in spite of all I have done for her." Mrs. Huntington spoke with a rancor that was really astounding to Molly, whose own mother was so different that the girl had an idea that all mothers must have some of Mrs. Brown's qualities.

"Oh, I am sure you are mistaken in judging your daughter thus severely! She must have inherited from George some other traits along with the artistic talent."

"That is just it. She inherited from him this very tendency to be hard on me. Was it kind or right for George to leave all the money to her; and to me, his devoted and long-suffering wife, nothing more than the law exacted? My only hope is that she may marry a man rich enough to make a handsome settlement on me. One who will have money enough not to regard Elise's fortune at all, except, perhaps, to realize the necessity of turning it over to me. Now tell me: do you think the Latin Quarter a likely place for a girl to find such a husband?"

"Oh, I don't know. You did pretty well there, and if you had waited for me, you might have done even better from a financial standpoint, as I have been very successful as the world takes it. Perhaps poor little Elise might have equal luck. Oh, Lizzie, Lizzie, how changed you are! You have spoken only of money and position and society; never once of love and humanity. I can't bear to see you this way. When I think of you as a girl with your soft, sweet manner and no more worldliness than a kitten, I can hardly bear to contemplate this change in you."

"Oh la, la, Tom, you and I know that a kitten only takes a year to grow into a horrid cat, and as you so brutally and frankly put it, I have had about twenty-five years to grow and sharpen my claws. You struck this note first in our conversation. I was prepared to be as nice as you once thought me, but I saw how cynical you had grown and I knew there was no use in putting on; so I have rather enjoyed showing you my true self. Anyhow, you are grateful to me for throwing you over, now that you see what I am. Is it not so?"

Mr. Kinsella did not answer for a moment, but finally said, changing the subject: "There is one thing I am going to ask of you for auld lang syne and I think maybe you will grant it: let Elise put in this winter in a good studio in Paris. She is hungry for a long period of uninterrupted work and I know it will soften her toward you instead of hardening her; and I feel sure that when the dreaded twenty-fifth birthday arrives, she will want to settle half of the fortune on you. Do this for me, Lizzie. I guarantee it will come out well for you."

Mrs. Huntington hesitated for a moment and then by a quick calculation came to the conclusion that it would be a good thing, after all, and would leave her free to go where she chose. She well knew how cheaply a girl could board in Paris when she was at work in a studio, and, as Tom said, there was every chance of her picking up a rich husband among the students. There were always some young men who were rolling in wealth, but still had the artistic bee in their bonnets.

"I'll do it, Tom, but if it turns out badly I'll have you to thank."

"Lizzie, now you are more like your old self and I am grateful to you for this concession. Come, let us find Elise and tell her the good news."

Molly was indeed glad to have the interview over. It was against her whole honest nature to eavesdrop, but she felt it best for all concerned for her to remain quiet. As soon as Mr. Kinsella and Mrs. Huntington had disappeared, Molly beat a hasty retreat to her stateroom where her mother was looking for her, not being able to find her on deck.

"Oh, Mother, I am so excited!" And she told Mrs. Brown all about her forced concealment during the intimate conversation between the old lovers.

"It is very interesting, certainly, and I hardly know how you could help being a listener. Since it will go no farther, as of course neither of us will ever mention the matter to a soul, it will do no harm. I wish you had not had to hear it, however, as I hate for my Molly to realize that such women as Mrs. Huntington exist, so cold and selfish and worldly. I am glad poor Elise is to be allowed to stay in Paris all winter and work. Perhaps we can make up to her some for her mother's heartlessness."

So mother and daughter kissed and went to bed; Molly waked the next morning with no trace of seasickness, ready and eager to enjoy the rest of the voyage.

The trip was delightful to both mother and daughter. They made many acquaintances on board, but Elise O'Brien and the two Kinsellas they counted among their real friends. So closely were the five thrown together on the voyage, that they often said it seemed as though they had known one another all their lives. Mrs. Huntington kept to herself much of the time. She seemed to realize that it was policy to let Elise have as good a time as she could with her father's old friend and his nephew; and since the Browns seemed to have influential and wealthy friends, they could, at least, do her daughter no harm, and might even prove useful during the girl's sojourn in Paris.

Elise bloomed in this congenial atmosphere and did not look like the same girl. She had a ready wit, was quick at repartee, and after a while her tongue lost its bitterness and her sarcastic humor became much more genial.

Mr. Kinsella would often say: "That is like your father. He had the kindest humor in the world and was truly Irish in his wit." But when she was too critical or inclined to let her wit run away with her heart, he would shake his head and look sad; and the girl began to care what her father's friend thought of her, and tried to please him.

She had liked Molly from the minute they clasped hands when Pierce introduced them, and this liking grew to enthusiastic love. She had had few intimates and this friendship was wonderful to her. Mr. Kinsella realized the importance of this wholesome influence on his charge, (he had made Elise his charge ever since he wrung from her mother the promise to let her continue her studies in art), and he did everything to throw the girls together and give them opportunities to talk their eager girls' talk.

"I hate to think of the journey coming to an end," said Molly. "It has been splendid; but if the trip is nearly over, our friendship has just begun! And what times we can have in Paris! Isn't it great that you and Judy know each other and that the three of us are so congenial?"

Elise looked sad. "Yes, it is fine, but I know you and Judy will want me out of the way. You are such old friends, and I shall always feel like an interloper."

"Oh, Elise, Elise! You must not feel that way for an instant. Judy and I love each other a whole lot, but we are not a bit inclined to pair off and not make new friends. Judy is more than likely already to have begun a big affair of friendship with somebody. She will get so thick with that one that she will have no time for anyone else; and then she will find out the person is not the paragon she had imagined and come weeping back to me," said Molly, throwing her arm around Elise and giving her a warm hug.

"Well, let's enjoy the few hours left to us. It seems hardly possible that this is the same, stupid old boat that we boarded a little over a week ago. I hated it, our stuffy stateroom, the crowded table; and then I always dread a long voyage with Mamma. She gets so cross and overbearing when she is cut off from society and amusements and——" Elise stopped suddenly. She felt Molly's friendly arm growing slack around her waist and she realized that her new friends, the Browns, could not tolerate her impertinent remarks to and about her mother. "Oh, Molly, please excuse me. I am trying to be nicer about Mamma. It is awfully ill-bred of me to speak of her in that way, no matter how I feel."

"Elise, why don't you try to feel differently and then it would be impossible for you to speak so?"

"Oh, Molly, I will try." And it shows she was already trying, for she did not add what was in her heart to say, "If you only knew my mother you would not ask that of me."

"Judy! Judy! I can't believe that we are really here, that this is Paris, and that you are you! As for me, I feel like 'there was an old woman as I've heard tell' who said 'Lawk a mercy on me, this surely can't be I.'"

Molly settled herself with a sigh of supreme enjoyment on the lumpy seat of an extremely rickety taxi that Judy had engaged to take the Browns from the station to Mrs. Pace's very exclusive pension on the Boulevard St. Michel.

"It does seem almost too good to be true that I have got you and your dear mother at last. I have not been able to work for a week because of the excitement of expectation. I went over to Monroe's this morning and got your mail. I could hardly lug it home, both of you had such a batch. You see, the mail has beaten your slow steamer in and everyone is writing to have a greeting ready for you in Paris." And Judy, who was in the middle, put embracing arms around both Mrs. Brown and Molly as they rode down the Avenue de l'Opera.

How wonderful Paris looked to them on that clear, crisp day in autumn! She was showing her best and most smiling aspect to the travelers, which delighted Judy, as she felt quite responsible for her beloved city and wanted her friends to like it as much as she did. They passed various points of interest which Judy pointed out with pride, and which brought answering thrills from Mrs. Brown and Molly.

The streets were gay with little pushcarts, laden with chrysanthemums and attended by the most delightful looking old women. Everyone seemed to be in a good humor and no one in much of a hurry except the chauffeurs, and they went whizzing by at a most incredible speed through the crowded thoroughfares.

"How clean the streets are!" exclaimed Mrs. Brown. "And what a good smell!"

"Oh, I just wondered if you would notice the smell! That is Paris. 'Every city has an odor of its own,' Papa says, and I believe he is right. Paris smells better than New York, although I like the smell in New York, too; but Paris has a strange freshness in its odor that reminds me of flowers and good things to eat, and suggests gay times, rollicking fun and adventure."

"Same old Judy," laughed Molly, "with her imagination on tap."

Just then they ran under the arches of the Louvre into the Place du Carrousel, and Molly held her breath with wonder and delight. Then came the Seine with its beautiful bridges, its innumerable boats, and its quays with the historic secondhand book stalls where Edwin Green had looked forward to walking with her, searching for treasures of first editions and what not. "Never mind," thought Molly, "Professor Green may come later and the first editions will keep."

"There is the wonderful statue of Voltaire, and through this street you can catch a glimpse of the Beaux Arts," chanted Judy. "Now look out, for before you know it we will be in the aristocratic Faubourg St. Germain,—and then the Luxembourg Gardens,—and here we are at our own respectable door before we are ready for it! Now Mrs. Pace will eat both of you up for a while and I cannot get a word in edgewise."

The Pension Pace was on the corner where a small street ran into the broad boulevard at a sharp angle, making the building wedge-shaped. It was a very imposing looking house and Mrs. Brown wondered at a woman being able to conduct such a huge affair. She expressed her surprise to Judy, who informed her that Mrs. Pace had only the three upper floors and that the other flats were let to different tenants.

"The elevator takes us to the fifth floor, where Mrs. Pace has her parlors, dining salon and swellest boarders,—at least the boarders able to pay the most. Of course we do not think that they are the swellest, since we are on the seventh floor ourselves. Who so truly swell as we?" Judy got out of the taxi with such an assumption of great style that the chauffeur, much impressed, demanded a larger pourboire than she saw fit to give him.