| VOL. XIX, NO. 537.] | SATURDAY, MARCH 10, 1832. | [PRICE 2d. |

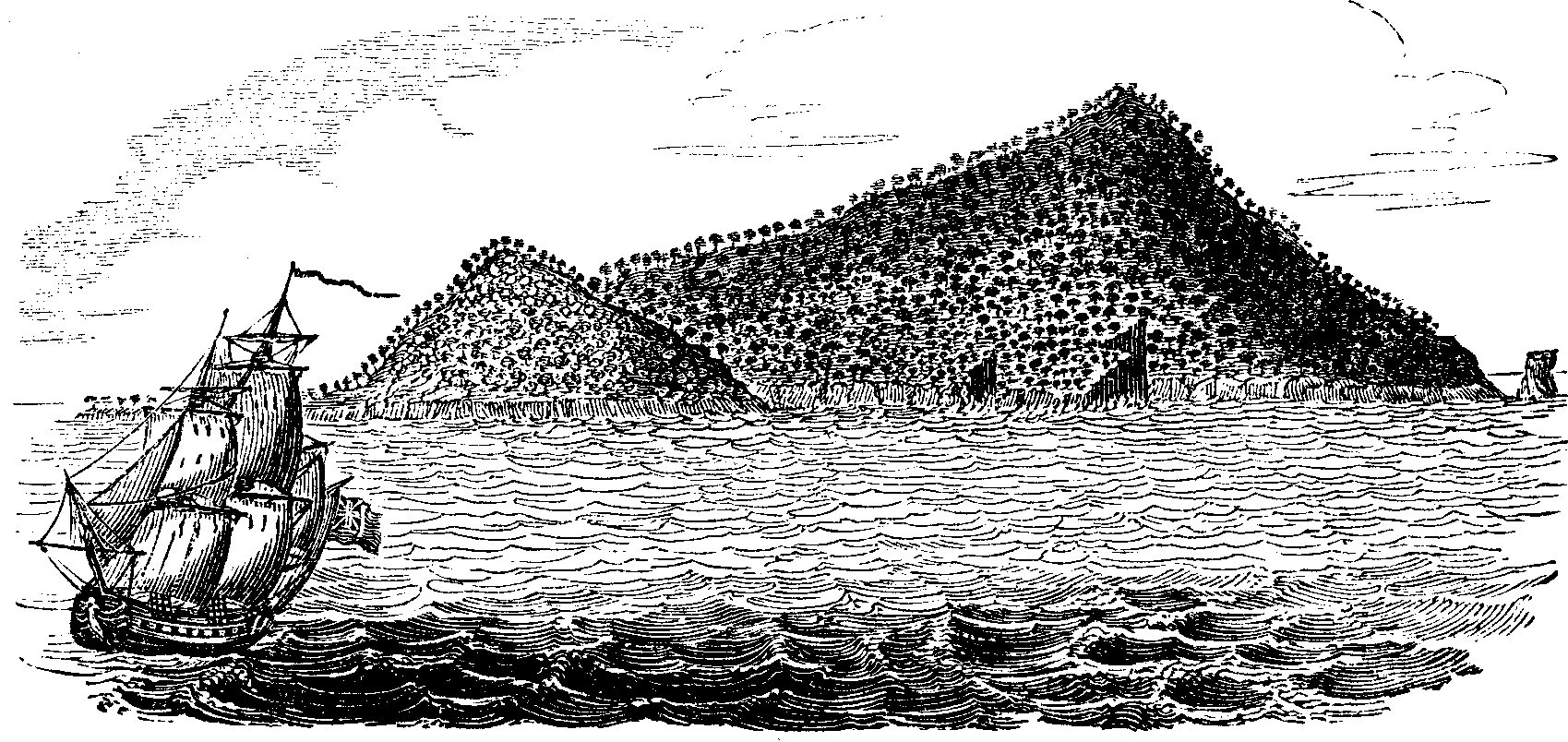

Mr. George Bennett,1 whose "Journals" and "Researches" denote him to be a shrewd and ingenious observer, has favoured us with the original sketches of the above cuts. They represent three of the spots that stud the Southern Pacific Ocean. The first beams with lovely luxuriance in its wood-crowned heights; while the second and third rise from the bosom of the sea in frowning sterility [pg 146] amidst the gay ripple that ever and anon laves their sides, and plashes in the brilliancy of the sunbeam.

Tucopia, or Barwell's Island, has recently been elsewhere described by Mr. Bennett.2 His sketch includes the S.W. side of the island, and his entertaining description is as follows:

"This small but elevated and wooded island was discovered by the ship Barwell in 1798; it was afterwards (1810) visited by the French navigators, who called it by the native name Tucopia. On the S.W. side of the island is a wooded, picturesque valley, surrounded by lofty mountains, and containing a small but well-inhabited village. Two singularly isolated basaltic rocks, of some elevation, partially bare, but at parts covered by shrubs, rise from about the centre of the valley. When close in, two canoes came off containing several natives, who readily came on board; two of them had been in an English whaler, (which ships occasionally touched at the island for provisions, &c.) and addressed us in tolerable English. They were well formed, muscular men, with fine and expressive features, of the Asiatic race, in colour of a light copper; they wore the hair long, and stained of a light brown colour; they were tattooed only on the breast, which had been executed in a neat vandyked form; the ears, as also the septum narium, were perforated, and in them were worn tortoiseshell rings; around the waist was worn a narrow piece of native cloth (died either of a dark red or yellow colour), or a small narrow mat formed from the bark of a tree, and of fine texture; some of these had neatly-worked dark red borders, apparently done with the fibres of some dyed bark. They rub their bodies with scented cocoa-nut oil as well as turmeric. The canoes were neatly constructed, had outriggers, and much resemble those of Tongatabu; the sails were triangular, and formed of matting. No weapons were observed in the possession of any of the natives; they said they had two muskets, which had been procured in barter from some European ship. We landed on a sandy beach, and were received by a large concourse of natives. We were introduced to a grave old gentleman, who was seated on the ground, recently daubed with turmeric and oil for this ceremony; he was styled the ariki, or chief, of this portion of the island. On an axe, as well as other presents, being laid before him, he (as is usual among the chiefs of the Polynesian Islands on a ceremonial occasion) did not show any expression of gratification or dislike at the presents but in a grave manner made a few inquiries about the ship. Near the ariki sat a female, whose blooming days had passed; she was introduced as his wife; her head was decorated with a fillet of white feathers; the upper part of her body was exposed, but she wore a mat round the waist which descended to the ankles; the chief was apparently a man of middle age.

"The native habitations were low, of a tent form, and thatched with cocoa-nut leaves; these habitations were not regular, but scattered among the dense vegetation which surrounded them on all sides. The tacca pinnatifida, or Polynesian arrow-root plant, called massoa by the natives, was abundant, as also the fittou, or calophyllum inophyllum, and a species of fan palm, growing to the height of fifteen and twenty feet, called tarapurau by the natives; the areka palm was also seen, and the piper betel was also cultivated among them. They had adopted the oriental custom of chewing the betel; in using this masticatory they were not particular about the maturity of the nuts, some eating them very young as well as when quite ripe; they carried them about enclosed in the husk, which was taken off when used.3 At a short distance from the beech, inland, was a lake of some extent, nearly surrounded by lofty, densely-wooded hills. Some wild ducks were seen, and a gun being fired at them, the report raised numbers of the 'plumy tribe,' filling the air with their screams, alarmed at a noise to which they had been unaccustomed. Several native graves were observed, which were very neat; a stone was placed at the head and the grave neatly covered over by plaited sections of the cocoa-nut frond; no particular enclosures for the burial of the dead were observed. When rambling about, the 'timid female' fled at our approach. From a casual glimpse of the fair objects, they merit being classed among the 'beautiful portion of the creation;' their hair was cut close.

"Cooked yams, cocoa-nuts, &c. were brought us by the natives, and their manner was very friendly; of provisions, yams, hogs, &c. could be procured. [pg 147] The natives were anxious to accompany us on the voyage, and it was with the greatest difficulty that we could get rid of them. It seems they have occasional intercourse with islands at some distance from them; two fine polished gourds, containing lime, &c. used with their betel, were observed among them—one was plain and the other ornamented with figures, apparently burnt by some instrument. They stated that these had been procured from the island of Santa Cruz (Charlotte's Archipelago) by one of the chief's sons. Some of the natives were observed much darker than others, and there appeared a mixture of some races. Their numerals were as follows:—

"1 Tashi.

2 Rua.

3 Toru.

4 Fa.

5 Hima.

6 Ono.

7 Fithu.

8 Warru.

9 Hiva.

10 Tanga, foru."

The isolated basaltic rocks in the centre of the valley may give rise to some curious speculations on the origin of this island. It has long been decided that basaltic rocks are of igneous origin, in opposition to the theory of Werner—that they were deposited by the ocean on the summits of elevated mountains. May not the occurrence of these basalt rocks therefore illustrate the more immediate volcanic origin of Tucopia?

The second Cut represents the PIERCY ISLANDS, two barren islets situated a short distance off Cape Bret, (New Zealand,) near the entrance of the Bay of Islands: one is of very small size, and appears connected to the other by a ledge of rocks visible at low water. The larger one is quoin shaped, and has a remarkable perforation, seen in the sketch.

One of the residences of this historian and poet, was about a mile from Paddington on the north side of the Edgware Road, near a place called Kilburn Priory; and the wooden cottage is still standing, although the land near it has been of late covered with newly-erected villas. It is occupied by a person in humble life, and is not to be altered or removed owing to the respect entertained for the memory of this remarkable literary character. In this cottage, Goldsmith wrote his admirable treatise on Animated Nature. A sketch of this rustic dwelling is a desideratum, as, in after days, it may be demolished to make way for modern improvement.

Mild genius of the silent eve!

Thy pathway through the radiant skies,

Is the rich track which sunbeams weave

With all their varied, mingling, dyes,

Ere yet the lingering sun has fled,

Or glory left the mountain's head.

Yet not one ray of sunset's hue

Illumes thy silent, peaceful train;

And scarce a murmur trembles through

The woods, to hail thy gentle reign,

Save where the nightingale, afar,

Sings wildly to thy lonely star.

Yet gentlest eve, attending thee,

Come meek devotion, peace, and rest,

Mild contemplation, memory,

And silence with her sway so blest;

And every mortal wish and thought,

By thee to holiest peace is wrought.

Thine airs that crisp the quiet stream,

Are soft as slumbering infants' breath:

The trembling stars, that o'er thee beam,

Are pure as Faith's own crowning wreath:

And e'en thy silence has for me

A charm more sweet than melody.

Oh gentle spirit, blending all

The beauties parting day bestows,

With deeper hues that slowly fall,

To shadow Nature's soft repose;

So sweet, so mild, thy transient sway,

We mourn it should so soon decay.

But like the loveliest, frailest things

We prize on earth, thou canst not last;

For scarce thine hour its sweetness brings

To soothe, and bless us, e'er 'tis past;

And night, dull cheerless night destroys

Thy tender light, and peaceful joys.

I observe a communication respecting my little note on the shrimp in one of your recent Numbers. Whether shrimps or not, I was not aware of my error, for they closely resembled them, and were not "as different as possible," as H.W. asserts. Every person too, must have remarked the agility of the old shrimp when caught. They were besides of various sizes, many being much larger that what H.W. means as the "sea flea." Perhaps H.W. will be good enough to describe the size of the latter when he sends his history of the shrimp.

With regard to the "encroachers," my information must have been incorrect. I had omitted, accidentally however, in the hurry of writing, to add "if undisturbed for a certain period," to the passage quoted in page 20 of your No. 529.

In North Wales, some years ago, there were some serious disturbances [pg 148] concerning an invasion of the alleged rights of the peasantry, but I do not now remember the particulars. Few things by the way, have been attended with more mischievous effects in England than the extensive system of inclosures which has been pursued within the last thirty years. No less than 3,000 inclosure acts have been passed during that period; and nearly 300,000 acres formerly common, inclosed: from which the poor cottager was once enabled to add greatly to his comfort, and by the support thus afforded him, to keep a cow, pigs, &c.

I attended a meeting at Exeter Hall, the other day, of the "Labourers' Friend Society," whose object is to provide the peasantry with small allotments of land at a low rent. This system, if extensively adopted, promises to work a wonderful change for the better in the condition of the working classes. Indeed the system where adopted has already been attended with astonishing results. When we come to consider that out of the 77,394,433 acres of land in the British Isles, there are no less than 15,000,000 acres of uncultivated wastes, which might be profitably brought under cultivation; it is surprising to us, that instead of applying funds for emigration, our legislators have so long neglected this all-important subject. Of the remaining 62,394,433 acres, it appears that 46,522,970 are cultivated, and 15,871,463 unprofitable land. The adoption of the allotment system has been justly characterized as of national importance, inasmuch as it diminishes the burdens of the poor, is a stimulus to industry, and profitably employs their leisure hours; besides affording an occupation for their children, who would otherwise, perhaps, run about in idleness.

In the reign of Elizabeth, no cottager had less than four acres of land to cultivate; but it has been found that a single rood has produced the most beneficial effects. We need scarcely add that where adopted, it has very greatly reduced the poor-rates. The subject is an interesting one, and, I trust, we shall in a short period hear of the benevolent and meritorious objects of the Society being extensively adopted. We refer the reader to some remarks on the subject in connexion with the Welsh peasantry, &c. in The Mirror, No. 505.

In our description of Swansea, in No. 465, we mentioned the facility with which the harbour could be improved, and the importance of adapting it for a larger class of shipping than now frequent that port. On a recent visit to South Wales, we found this improvement about to be carried into effect, and an act is to be obtained during the present session of Parliament. A new harbour on an extensive scale, is also about to be commenced near Cardiff. The increase of population in Wales has been very considerable since the census of 1821. Wales contains a superficies of 4,752,000 acres; of which 3,117,000 are cultivated; 530,000 capable of improvement, and 1,105,000 acres are unprofitable land.

But here come the graces of the forest, fifty at least in the herd—how beautifully light and airy; elegance and pride personified; onward they come in short, stately trot, and tossing and sawing the wind with their lofty antlers, like Sherwood oak taking a walk; heavens! it is a sight of sights. Now advance in play, a score of fawns and hinds in front of the herd, moving in their own light as it were, and skipping and leaping and scattering the dew from the green sward with their silvery feet, like fairies dancing on a moonbeam, and dashing its light drops on to the fairy ring with their feet of ether. O! it was a sight of living electricity; our very eyes seemed to shoot sparks from man to man, and even the monkey himself, as we gazed at each other in trembling suspense.

"Noo, here they coom wi' their een o' fire an' ears o' air," whispered the Ettric poet.

"Hush," quoth I, "or they'll be off like feathers in a whirlwind, or shadows of the lights and darks of nothingness lost in a poet's nightmare."

"A sumph ye mean," answered Jammie.

"Hush, there they are gazing in the water, and falling in love with their own reflected beauty."

"Mark the brindled tan buck," whispered one keeper to the other. They fired together, and both struck him plump in his eye of fire; mine seemed to drop sparks with sympathy: he bounded up ten feet high—he shrieked, and fell stone dead; Gods, what a shriek it was; I fancy even now I have that shriek and its hill-echo chained to the tympanum of my ear, like the shriek of the shipwrecked hanging [pg 149] over the sea—heavens! it was a pity to slay a king I thought, as I saw him fall in his pride and strength; but by some irresistible instinct, my own gun, pulled, I don't know how, and went off, and wounded another in the hip, and he plunged like mad into the river, to staunch his wounds and defend himself against the dogs. Ay, there he is keeping them at bay, and scorning to yield an inch backward; and now the keeper steals in behind him and lets him down by ham-stringing him: but when he found his favourite dog back-broken by the buck, why he cursed the deer, and begged our pardon for swearing; and now he cuts a slashing gash from shoulder to chop to let out the blood; and there lay they, dead, in silvan beauty, like two angels which might have been resting on the pole, and spirit-stricken into ice before they had power to flee away.

But we must away to Sir Reynard's hall, and unsough him; this we can do with less sorrowful feelings than killing a deer, which indeed, is like taking the life of a brother or a sister; but as to a fox, there is an old clow-jewdaism about him, that makes me feel like passing Petticoat-lane or Monmouth-street, or that sink of iniquity, Holy-well-street. O, the cunning, side-walking, side-long-glancing, corner-peeping, hang-dog-looking, stolen-goods-receiving knave; "Christian dog" can hold no sympathy with thee, so have at thee. Ah, here is his hold, a perfect Waterloo of bones.

"The banes o' my bonnie Toop, a prayer of vengeance for that; an' Sandy Scott's twa-yir-auld gimmer, marterdum for that." "An' my braxsied wether," quoth a forester; "the rack for that, and finally the auld spay-wife's bantam cock, eyes and tongue cut out and set adrift again, for that." Now we set to work to clear his hole for "rough Toby" (a long-backed, short-legged, wire-haired terrier of Dandy Dinmont's breed) to enter; in he went like red-hot fire, and "ready to nose the vary deevil himsel sud he meet him," as Jammie Hogg said; and to see the chattering anxiety of the red-coated monkey, as he sat at the mouth of the fox-hole, on his shaggy, grizzle-grey shadow of a horse, like a mounted guardsman in the hole yonder at St. James's; it truly would have made a "pudding creep" with laughter—"Reek, reek, reeking into th' hole after Toby, with his we we cunnin, pinkin, glimmerin een, an' catchin him 'bith stump o' th' tail as he were gooin in an' handing as long as he could," as James said. O, it was a very caricature of a caricature. But list, I hear them scuffle, they are coming out. Notice the monkey shaking his "bit staff;" here they come like a chimney swept in a hurry, they are out. "What a gernin, glowerin, sneerin, deevilitch leuk can a tod gie when hee's keepit at bay just afore he slinks off," exclaimed the poet, as Reynard was stealing away; but yonder they go before the wind, down the sweeping, outstretched glen, like smoke in a blast. Ay, there they go, two stag hounds, monkey, and grew, and Toby yelping behind; what a view we have of them—the grew is too fleet for him, he turns him and keeps him at bay till the hounds come up; now they are off again, and now we lose them, vanished like the shadow of a dream.

We followed, and on our way we met a herdsman, with his eyes staring like two bullets stuck in clay, or rather two currants stuck in a pudding: he said he had met "the deevil, a' dress'd like a heelanman o' tod huntin;" of course we laughed from the bottom end of our very bowels; but that was not the way to undemonize him, no, he pledged himself that he saw him "wi' his own twa een lowp off the shoather o' a thing lik a snagged foal, an' gie the tod such a dirl 'ith heed, that he kilt him deed's a herrin, an' we micht a' witness the same by gannin to the Shouther o' Birkin Brae." And truly it was as he said, for we found the mark of the little Highlandman's shillela on the fox's head, while he himself was sitting a straddle on him, like "the devil looking over Lincoln Minster," and the dogs lying panting round about.

On our road home to Hogg's we paid a visit to a wild-cat's lair in the Eagle's Cragg, and of all the incarnate devils, for fighting I ever saw, they "cow the cuddy," as the Scotch say; perfect fiends on earth. There was pa and ma, or rather dad and mam, (about the bigness of tiger-cats, one was four feet and a half from tip to tail) and seven kittens well grown; and O, the spit, snarl, tusshush and crissish, and mow-waaugh they did kick up in their den, whilst in its darkness we could see the electricity or phosphorescence of their eyes and hair sparkling like chemical fire-works. But I must tell you the rest hereafter, for my paper is out!

Mr. Haydon has nearly completed his Xenophon, which he intends to make the nucleus of an Exhibition during the present town season. The King has graciously lent Mr. Haydon the Mock Election picture; (for an Engraving of which see Mirror, vol. xi. p. 193,) for the above purpose. There will be other pictures, of comic and domestic interest by the same artist; among which will be Waiting for the Times, (purchased by the Marquess of Stafford;) The First Child, very like papa about the eyes, and mamma about the nose; Reading the Scriptures; Falstaff and Pistol; Achilles playing the Lyre; and others, which with a variety of studies, will make up an interesting Exhibition.

The following is a translation of the leaf from the journal of Dr. Martins, dated Para, August 16, 1819; and describes an equatorial day, as observed near the mouths of the Para and the Amazons:—

How happy am I here! How thoroughly do I now understand many things which before were incomprehensible to me! The glorious features of this wonderful region, where all the powers of nature are harmoniously combined, beget new sensations and ideas. I now feel that I better know what it is to be a historian of nature. Overpowered by the contemplation of an immense solitude, of a profound and inexpressible stillness, it is, doubtless, impossible at once to perceive all its divine characteristics; but the feeling of its vastness and grandeur cannot fail to arouse in the mind of the beholder the thrilling emotions of a hitherto inexperienced delight.

It is three o'clock in the morning, I quit my hammock; for the excitement of my spirits banishes sleep. I open my window, and gaze on the silent solemnity of night. The stars shine with their accustomed lustre, and the moon's departing beam is reflected by the clear surface of the river. How still and mysterious is every thing around me! I take my dark lantern, and enter the cool verandah, to hold converse with my trusty friends the trees and shrubs nearest to our dwelling. Most of them are asleep, with their leaves closely pressed together; others, however, which repose by day, stand erect, and expand themselves in the stillness of night. But few flowers are open; only those of the sweet-scented Paullinia greet me with a balmy fragrance, and thine, lofty mango, the dark shade of whose leafy crown shields me from the dews of night. Moths flit, ghost-like, round the seductive light of my lantern. The meadows, ever breathing freshness, are now saturated with dew, and I feel the damp of the night air on my heated limbs. A Cicàda, a fellow-lodger in the house, attracts me by its domestic chirp back into my bedroom, and is there my social companion, while, in a happy dreaming state, I await the coming day, kept half awake by the buzz of the mosquites, the kettle-drum croak of the bull-frog, or the complaining cry of the goatsucker.

About five o'clock I again look out, and behold the morning twilight. A beautiful even tone of grey, finely blended with a warmth-giving red, now overspreads the sky. The zenith only still remains dark. The trees, the forms of which become gradually distinct, are gently agitated by the land wind, which blows from the east. The red morning light and its reflexes play over the dome-topped caryocars, bertholetias, and symphonias. The branches and foliage are in motion, and all the lately slumbering dreamers are now awake, and bathe in the refreshing air of the morning. Beetles fly, gnats buzz, and the varied voice of the feathered race resounds from every bush; the apes scream as they clamber into the thickets; the night moths, surprised by the approach of light, swarm back in giddy confusion to the dark recesses of the forest; there is life and motion in every path; the rats and all the gnawing tribe are hastily retiring to their holes, and the cunning marten, disappointed of his prey, steals from the farm-yard, leaving untouched the poultry, to whom the watchful cock has just proclaimed the return of day.

The growing light gradually completes the dawn, and at length the effulgent day breaks forth. It is nature's jubilee. The earth awaits her bridegroom, and, behold, he comes! Rays of red light illumine the sky, and now the sun rises. In another moment he is above the horizon, and, emerging from a sea of fire, he casts his glowing rays upon the earth. The magical twilight is gone; bright gleams flit from point to point, accompanied by deeper and deeper shadows. Suddenly the enraptured observer beholds around him the joyous earth, arrayed in fresh dewy splendour, the fairest of brides. The vault of heaven is cloudless; on the earth all is instinct [pg 151] with life, and every animal and plant is in the full enjoyment of existence. At seven o'clock the dew begins to disappear, the land breeze falls off, and the increasing heat soon makes itself sensibly felt. The sun ascends rapidly and vertically the transparent blue sky, from which every vapour seems to disappear; but presently, low in the western horizon, small, flaky, white clouds are formed. These point towards the sun, and gradually extend far into the firmament. By nine o'clock the meadow is quite dry, the forest appears in all the splendour of its glowing foliage. Some buds are expanding; others, which had effloresced more rapidly, have already disappeared. Another hour, and the clouds are higher: they form broad, dense masses, and, passing under the sun, whose fervid and brilliant rays now pervade the whole landscape, occasionally darken and cool the atmosphere. The plants shrink beneath the scorching rays, and resign themselves to the powerful influence of the ruler of the day. The merry buzz of the gold-winged beetle and humming-bird becomes more audible. The variegated butterflies and dragon-flies on the bank of the river, produce, by their gyratory movements, lively and fantastic plays of colour. The ground is covered with swarms of ants, dragging along leaves for their architecture. Even the most sluggish animals are roused by the stimulating power of the sun. The alligator leaves his muddy bed, and encamps upon the hot sand; the turtle and lizard are enticed from their damp and shady retreats; and serpents of every colour crawl along the warm and sunny footpaths.

But now the clouds are lowering; they divide into strata, end, gradually getting heavier, denser, and darker, at last veil the horizon in a blueish grey mist. Towards the zenith they tower up in bright broad-spreading masses, and assume the appearance of gigantic mountains in the air. All at once the sky is completely overcast, excepting that a few spots of deep blue still appear through the clouds. The sun is hid, but the heat of the atmosphere is more oppressive. The noontide is past; a cheerless melancholy gloom hangs heavily over nature. Fast sink the spirits; for painful is the change to those who have witnessed the joyous animation of the morning. The more active animals roam wildly about, seeking to allay the cravings of hunger and thirst; only the quiet and slothful, who have taken refuge in the forest, seem to have no apprehension of the dreadful crisis. But it comes! it rushes on with rapid strides, and we shall certainly have it here. The temperature is already lowered; the fierce and clashing gales tear up trees by the roots. Dark and foaming billows swell the surface of the deeply agitated sea. The roar of the river is surpassed by the sound of the wind, and the waters seem to flow silently into the ocean. There the storm rages. Twice, thrice, flashes of pale blue lightning traverse the clouds in rapid succession: as often does the thunder roll in loud and prolonged claps through the firmament. Drops of rain fall. The plants begin to recover their natural freshness; it thunders again, and the thunder is followed, not by rain, but by torrents, which pour down from the convulsed sky. The forest groans; the whizzing rustle of the waving leaves becomes a hollow murmuring sound, which at length resembles the distant roll of muffled drums. Flowers are scatterd to and fro, leaves are stripped from the boughs, branches are torn from the stems, and massy trees are overthrown; the terrible hurricane ravishes all the remaining virgin charms of the levelled and devastated plants. But wherefore regret their fate? Have they not lived and bloomed? Has not the Inga twisted together its already emptied stamens? Have not the golden petals fallen from the fractified blossoms of the Banisèria, and has not the fruit-loaded Arum yielded its faded spathe to the storm? The terrors of this eventful hour fall heavily even on the animal world. The feathered inhabitants of the woods are struck dumb, and flutter about in dismay on the ground; myriads of insects seek shelter under leaves and trunks of trees. The wild Mammàlia are tamed, and suspend their work of war and carnage; the cold-blooded Amphíbia alone rejoice in the overwhelming deluge, and millions of snakes and frogs, which swarm in the flooded meadows, raise a chorus of hissing and croaking. Streams of muddy water flow through the narrow paths of the forests into the river, or pour into the cracks and chasms of the soil. The temperature continues to descend, and the clouds gradually empty themselves.

But at length a change takes place, and the storm which lately raged so furiously is over. The sun shines forth with renovated splendour through long extended masses of clouds, which gradually disperse towards the horizon on the north and south, assuming, as in the morning, light, vapoury forms, and hemming the azure basis of the firmament. A smiling deep blue sky now gladdens the earth, and the horrors of the past [pg 152] are speedily forgotten. In an hour no trace of the storm is visible; the plants, dried by the warm sunbeams, rear their heaps with renewed freshness, and the different kinds of animals obey, as before, their respective instincts and propensities.

Evening approaches, and new clouds appear between the white flaky fringes of the horizon. They diffuse over the landscape tints of violet and pale yellow, which harmoniously blends the lofty forests in the back-ground with the river and the sea. The setting sun, surrounded by hues of variegated beauty, now retires through the western portals of the firmament, leaving all nature to love and repose. The soft twilight of evening awakens new sensations in animals and plants, and buzzing sounds prove that the gloomy recesses of the woods are full of life and motion. Love-sighs are breathed through the fragrant perfumes of newly collapsed flowers, and all animated nature feels the influence of this moment of voluptuous tranquillity. Scattered gleams of light, reflected splendours of the departed sun, still float upon the woodland ridges; while, amidst a refreshing coolness, the mild moon arises in calm and silent grandeur, and diffusing her silver light over the dark forest, imparts to every object a new and softened aspect. Night comes;—nature sleeps, and the etheral canopy of heaven, arched out in awful immensity over the earth, sparkling with innumerable witnesses of far distant glories, infuses into the heart of man humility and confidence,—a divine gift after such a day of wonder and delight!—Mag. Nat. Hist. No. 24.

We are happy to learn that the celebrated Arundel MSS., which had been held for some time by the Royal Society, have recently been transferred to the British Museum; as well as a valuable addition of coins. In accordance with the suggestions made during the last Session of Parliament, the library of the Museum will henceforth be open to the public every day in the week, except Sundays.

During the past year 38,000 individuals visited the Museum, and very nearly 100,000, namely, 99,852 persons, from all parts of the kingdom, visited the Library for the purposes of study.

By the way, a livery-servant complained, in The Times of the 1st instant, that he had been refused admission to the Museum on an open and public day, in consequence of his wearing a livery, notwithstanding he saw "soldiers and sailors go in without the least objection." The Times remarks, "We believe livery-servants are not excluded from the sight at Windsor on an open day. We suspect that the regulation is not so much owing to any aristocratical notions on the part of the Directors of the Museum, as to that fastidious feeling which prevails in this country more than any other, and most of all among the lower ranks of the middle classes." The cause is reasonable enough; but we believe that livery-servants are not admitted at Windsor: the exclusion seems to be a caprice of Royalty, for servants are excluded from our palace-gardens, as Kensington. Surely this is unjust. If servants consent to wear liveries to gratify the vanity of their wealthy employers, it is hard to shut them out from common enjoyments on that account. This is in the true spirit of vassalage, of which the liveries are comparatively a harmless relic. In Paris we remember seeing a round-frocked peasant, apparently just from the plough, pacing the polished floor of the Louvre gallery with rough nailed shoes, and then resting on the velvet topped settees; and he was admitted gratis. Would such a person, tendering his shilling, be admitted to the Exhibition at Somerset House?

This is an excellent little work by Mr. Brande: it is not avowedly so, although everyone familiar with his valuable Manual of Chemistry will soon identify the authorship. The present is only the first Part of this petite system, containing Attraction, Heat, Light, and Electricity. It is, as the author intended it to be, "less learned and elaborate than the usual systematic works, and at the same time more detailed, connected, and explicit than the 'Conversations' or 'Catechisms.'" It avoids "all prolixity of language and the use of less intelligible terms;" and, to speak plainly, the illustrative applications throughout the work are familiar as household words. Witness the following extract from the effects of Heat:

"In consequence of the lightness of heated air, it always rises to the upper parts of rooms and buildings, when it either escapes, or, becoming cooled and [pg 153] heavier, again descends. If, in cold weather, we sit under a skylight in a warm room, a current of cold air is felt descending upon the head, whilst warmer currents, rising from our bodies and coming into contact with the cold glass, impart to it their excess of heat. Being thus contracted in bulk, and rendered specifically heavier, they in their turn descend, and thus a perpetual motion is kept up in the mass of air. This effect is attended with much inconvenience to those who inhabit the room, and is in great measure prevented by the use of double windows, which prevent the rapid cooling and production of troublesome currents in the air of the apartment.

"We generally observe, when the door of a room is opened, that there are two distinct currents in the aperture; which may be rendered evident by holding in it the flame of a candle. At the upper part it is blown outwards, but inwards at the lower part; in the middle, scarcely any draught of air, one way or other, is perceptible.

"The art of ventilating rooms and buildings is in a great measure dependent upon the currents which we are enabled to produce in air by changes of temperature, and is a subject of considerable importance. As the heated air and effluvia of crowded rooms pass upwards, it is common to leave apertures in or near the ceiling for their escape. Were it not, indeed, for such contrivances, the upper parts of theatres and some other buildings would scarcely be endurable; but a mere aperture, though it allows the foul air to escape, in consequence of its specific lightness, is also apt to admit a counter-current of denser and cold air, which pours down into the room, and produces great inconvenience. This effect is prevented by heating, in any convenient way, the tube or flue through which the foul air escapes. A constantly ascending current is then established; and whenever cold air attempts to descend, the heat of the flue rarefies and drives it upwards. Thus the different ventilators may terminate in tubes connected with a chimney; or they may unite into a common trunk, which may pass over a furnace purposely for heating it.

"In some of our theatres, the gas chandelier is made a very effectual ventilator. It is suspended under a large funnel, which terminates in a cowl outside the roof; and the number of burners heat the air considerably, and cause its very rapid and constant ascent through the funnel, connected with which there may be other apertures in the ceiling of the building. But in these and most other cases, we may observe that the vents are not sufficiently capacious; and the foul air from the house, and from the gas-burners themselves, not being able readily to escape, diffuses itself over the upper part of the building, and renders the galleries hot and suffocating—all which is very easily prevented by the judicious adjustment of the size of the ventilating channels to the quantity of air which it is requisite should freely pass through them.

"The small tin ventilators, consisting of a rotating wheel, which we sometimes see in window-panes, are perfectly useless, though it is often imagined, in consequence of their apparent activity, that they must be very effectual; but the fact is, that a very trifling current of air suffices to put them in motion, and the apertures for its escape are so small as to produce no effectual change in the air of the apartment: they are also as often in motion by the ingress as by the egress of air.

"From what has been said, it will be obvious that our common fires and chimneys are most powerful ventilators, though their good services in this respect are often overlooked. As soon as the fire is lighted, a rapid ascending current of air is established in the chimney, and consequently there must be a constant ingress of fresh air to supply this demand, which generally enters the room through the crevices of the doors and windows. When these are too tight, the chimney smokes or the fire will not draw; and in such cases it is sometimes necessary to make a concealed aperture in some convenient part of the room for the requisite admission of air, or to submit to sitting with a window or door partly open. Any imperfect action of the chimney, or descending current, is announced by the escape of smoke into the room, and is frequently caused by the flue being too large, or not sufficiently perpendicular and regular in its construction. When there is no fire, the chimneys also generally act as ventilators; and in summer there is often a very powerful current up them, in consequence of the roof and chimney-pots being heated by the sun, and thus accelerating the ascent of the air. In a well-constructed house there should be sufficient apertures for the admission of the requisite quantity of air into the respective rooms, without having occasion to trust to its accidental ingress through every crack and crevice that will allow it to pass. These openings [pg 154] may either be concealed, or made ornamental, and by proper management may be subservient to the admission of warm air in winter."

We quote the following scene from one of the Tales recently published in three volumes with the general cognomen of Chantilly. It is from the longest and most successful of the stories called "D'Espignac," in the time of Henri III., and, as our extract shows, the scenes and sketches exhibit considerable talent, and a certain graphic minuteness which has become very popular in modern novels. The tale itself is not to our purpose, but we promise the reader a petit souper of horrors from its perusal, especially to those who woo terror to delight them. The pen is young and feminine, and of high promise. The occasion of the following scene is an interview of one of the characters with Henri.

"It was a small dark apartment, hung round with tapestry, the ceiling richly decorated with massive ornaments of carved oak, and the floor covered with a dark-coloured carpet of Turkey manufacture, so thick and soft that the footsteps fell unheard as they advanced over it. It was here that the monarch usually spent his leisure hours, and various were the objects indicative of his tastes and habits scattered around, in a confusion which completely put to flight all ideas of study or devotion in the mind of the visiter. On a small table near the door were strewn divers preparations for the toilette, and cosmetics for improving the complexion, of which the King used quantities almost incredible, all prepared by his own hand; and the mixing and arranging of these formed his greatest delight and amusement. In the recesses on each side the window stood two highly-polished ebony cases, which Catherine de Medicis his mother had brought from Italy, for containing books and holy relics; but for this they were totally useless to the present royal owner, who applied them to a far different purpose. On the lower shelf next the ground, were arranged small ornamented baskets, in each of which, on satin cushions, reposed in regal luxury a litter of spaniel puppies, which, together with their pampered mother, did not fail to salute with deafening noise any stranger who entered. The messes, medicines, and food of these little favourites completely filled the upper shelves, or only disputed ground with the chains and collars of their predecessors, a few of whom, rescued from oblivion, stood on the top, seemingly ready as in life to fly out with inhospitable fury on the approach of intruders.

"The upper compartments of the window were of painted glass, and cast a dismal light through the apartment, while the lower panes were darkened by the hawk-mews raised on the terrace, that the King might enjoy the daily satisfaction of seeing the birds fed before his eyes. On a table near the window stood an inkstand, with various implements for writing, but from the sorry condition in which they appeared, and the confusion prevailing around, it was evident they were but seldom used. Small was the space, however, allotted to such unimportant objects. His Majesty had been deeply engaged during the morning tending a sick puppy, which having washed in sweet water, and combed with a gilt comb, he had adorned with ribbons, and placed in a basket by his side; mixing a scented paste for whitening the hands, preparing a wash for the skin, binding the broken leg of a wounded merlin, and finally seeking relief from such engrossing pursuits in the favourite recreation of disburdening a precious missal of its exquisite illuminations, in order to ornament the walls and enliven the chamber! It was at this table that Henri himself was seated, with his head resting on his hands, and apparently buried in thought. The noisy greeting of the spaniels as La Vallée entered caused him to start, and he turned towards the door an anxious unquiet look, bespeaking distrust and apprehension, which, however, quickly changed to one of pleasure as he heard the name and recognised the features of his visiter.

"The King was at that time in the very flower of his age, and yet he appeared no longer young. The cares of royalty, the murder of the Guises, had planted many a deep and lasting furrow on his brow, which time would have otherwise withheld for many years. His pallid cheek and sunken eye told of a mind but ill at ease. No art, no charm could restore the bloom and freshness which remorse for the past and fear for the future had long ago dispelled, never to return. And yet, with that sweet self-deception which all are so disposed to practise, he sought to banish reflection and beguile alarm in the pursuit of all kinds of frivolous amusements unworthy of his rank or station, and fancied he had succeeded in chasing care if for a moment he ceased to think.

"His costume even now was foppish and recherché. Much time had evidently been spent in adjusting the drooping leathers of his jewelled toque, and no pains had been spared in properly disposing the plaits of his fraise and ruffles, or in arranging the folds of his broidered mantle. The snow-white slippers, with the sky-blue roses, the silken hose and braided doublet, seemed better fitted for the parade of the courtly saloon than the privacy of the closet. The hand he extended to the Count was like that of a youthful beauty, rather than of one who had once wielded sword with the bravest. Every finger was adorned with a costly jewel, which flashed and sparkled in the light as he waved his hand in token of welcome, and, pointing to a chair, bade his visiter be seated."

Once upon a time there lived at Hamburgh a certain merchant of the name of Meyer—he was a good little man; charitable to the poor, hospitable to his friends, and so rich that he was extremely respected, in spite of his good nature. Among that part of his property which was vested in other people's hands, and called debts, was the sum of five hundred pounds owed to him by the Captain of an English vessel. This debt had been so long contracted that the worthy Meyer began to wish for a new investment of his capital. He accordingly resolved to take a trip to Portsmouth, in which town Captain Jones was then residing, and take that liberty which in my opinion should in a free country never be permitted, viz. the liberty of applying for his money.

Our worthy merchant one bright morning found himself at Portsmouth; he was a stranger to that town, but not unacquainted altogether with the English language. He lost no time in calling on Captain Jones.

"And vat?" said he to a man whom he asked to show him to the Captain's house, "vat is dat fine veshell yondare?"

"She be the Royal Sally," replied the man, "bound for Calcutta—sails to-morrow; but here's Captain Jones's house, Sir, and he'll tell you all about it."

The merchant bowed, and knocked at the door of a red brick house—door green—brass knocker. Captain Gregory Jones was a tall man; he wore a blue coat without skirts; he had high cheek bones, small eyes, and his whole appearance was eloquent of what is generally termed the bluff honesty of the seaman. Captain Gregory seemed somewhat disconcerted at seeing his friend—he begged for a little further time. The merchant looked grave—three years had already elapsed. The Captain demurred—the merchant pressed—the Captain blustered—and the merchant, growing angry, began to threaten. All of a sudden Captain Jones's manner changed—he seemed to recollect himself, begged pardon, said he could easily procure the money, desired the merchant to go back to his inn, and promised to call on him in the course of the day. Mynheer Meyer went home, and ordered an excellent dinner. Time passed—his friend came not. Meyer grew impatient. He had just put on his hat and was walking out, when the waiter threw open the door, and announced two gentlemen.

"Ah, dere comes de monish," thought Mynheer Meyer. The gentlemen approached—the taller one whipped out what seemed to Meyer a receipt. "Ah, ver well, I vill sign, ver well!"

"Signing, Sir, is useless; you will be kind enough to accompany us. This is a warrant for debt, Sir; my house is extremely comfortable—gentlemen of the first fashion go there—quite moderate, too, only a guinea a-day—find your own wine."

"I do—no—understand, Sare," said the merchant, smiling amiably, "I am ver vell off here—thank you—"

"Come, come," said the other gentleman, speaking for the first time, "no parlavoo Monsoo, you are our prisoner—this is a warrant for the sum of 10,000l. due to Captain Gregory Jones."

The merchant stared—the merchant frowned—but so it was. Captain Gregory Jones, who owed Mynheer Meyer 500l., had arrested Mynheer Meyer for 10,000l.; for, as every one knows, any man may arrest us who has conscience enough to swear that we owe him money. Where was Mynheer Meyer in a strange town to get bail? Mynheer Meyer went to prison.

"Dis be a strange vay of paying a man his monish!" said Mynheer Meyer.

In order to wile away time, our merchant, who was wonderfully social, scraped acquaintance with some of his fellow-prisoners. "Vat be you in prishon for?" said he to a stout respectable-looking man who seemed in a violent passion—"for vhat crime?"

"I, Sir, crime!" quoth the prisoner; [pg 156] "Sir, I was going to Liverpool to vote at the election, when a friend of the opposite candidate had me suddenly arrested for 2,000l. Before I get bail the election will be over!"

"Vat's that you tell me? arrest you to prevent your giving an honesht vote? is that justice?"

"Justice, no!" cried our friend, it's the Law of Arrest."

"And vat be you in prishon for?" said the merchant pityingly to a thin cadaverous-looking object, who ever and anon applied a handkerchief to eyes that were worn with weeping.

"An attorney offered a friend of mine to discount a bill, if he could obtain a few names to indorse it—I, Sir, indorsed it. The bill became due, the next day the attorney arrested all whose names were on the bill; there were eight of us, the law allows him to charge two guineas for each; there are sixteen guineas, Sir, for the lawyer—but I, Sir—alas my family will starve before I shall be released. Sir, there are a set of men called discounting attorneys, who live upon the profits of entrapping and arresting us poor folk."

"Mine Gott! but is dat justice?"

"Alas! No, Sir, it is the law of arrest."

"But," said the merchant, turning round to a lawyer, whom the Devil had deserted, and who was now with the victims of his profession; "dey tell me, dat in Englant a man be called innoshent till he be proved guilty; but here am I, who, because von carrion of a shailor, who owesh me five hundred pounts, takes an oath that I owe him ten thousand—here am I, on that schoundrel's single oath, clapped up in a prishon. Is this a man's being innoshent till he is proved guilty, Sare?"

"Sir," said the lawyer primly, "you are thinking of criminal cases; but if a man be unfortunate enough to get into debt, that is quite a different thing:—we are harder to poverty than we are to crime!"

"But, mine Gott! is that justice?"

"Justice! pooh! it's the law of arrest," said the lawyer, turning on his heel.

Our merchant was liberated; no one appeared to prove the debt. He flew to a magistrate; he told his case; he implored justice against Captain Jones.

"Captain Jones!" said the magistrate, taking snuff; "Captain Gregory Jones, you mean!"

"Ay, mine goot Sare—yesh!"

"He set sail for Calcutta yesterday. He commands the Royal Sally. He must evidently have sworn this debt against you for the purpose of getting rid of your claim, and silencing your mouth till you could catch him no longer. He's a clever fellow is Gregory Jones!"

"De teufel! but, Sure, ish dere no remedy for de poor merchant?"

"Remedy! oh, yes—indictment for perjury."

"But vat use is dat? You say he be gone—ten thousand miles off—to Calcutta!"

"That's certainly against your indictment!"

"And cannot I get my monish?"

"Not as I see."

"And I have been arreshted instead of him!"

"You have."

"Sare, I have only von vord to say—is dat justice?"

"That I can't say, Mynheer Meyer, but it is certainly the law of arrest," answered the magistrate; and he bowed the merchant out of the room.

Beautiful, O woman! the sun on flower and tree,

And beautiful the balmy wind that dreameth on the sea;

And softly soundeth in thine ear, the song of peasants reaping,

The dove's low chant among the leaves, its twilight vigil keeping.

And beautiful the hushing of the linnet in her nest,

With her young beneath her wings, and the sunset on her breast:

While hid among the flowers, where the dreamy bee is flitting,

Singing unto its own glad heart, the poet child is sitting.

It stirreth up the soul, upon the golden waves to see,

The galley lifting up her crowned head triumphantly—

Io! Io! now she laugheth like a Queen of Araby,

While Joy and Music strew with flowers the pathway of her Chariotry!

And beautiful unto thy soul, at summer time to wait,

Till Moonlight with her sweet pale feet, comes dancing to thy gate;

Thy violet-eyes upturn'd unto thy love with timid grace,

He feels thine arm about his neck, thy kisses on his face.

Beautiful, O gentle girl, these pleasant thoughts to thee,

These chosen sheaves, long harvested within thy memory!

But when thy face grows dim, with weariness and care,

Thy heart, forgetting all its songs, awaketh but to prayer!

Thou lookest for a gleeful face, thine opening eyes to greet,

While coldness gathers on thy breast, the shadow round thy feet—

[pg 157]Beautiful, O woman, the green earth and the flowers may be,

But sweeter in that hour the voice of thy First-born Child to thee!

The spirit of mine eyes is faint

With gazing on thy light;

I close my eyelids, but within,

Sweet, thou art shining bright,

Sitting amid the purple gloom,

Like a flower-bird at night!

Thy beauty walketh by my side

By the green wood, on the sea;

I hear thee in the bird that sings

Upon the orange-tree;

Thy face upon the haunted streams

Is looking up to me.

Gentle one, in grief I linger

Beside the glimmering nest,

Till evening sinketh in the flowers,

Like a weary fawn to rest,

Yea, my heart is sick with longing

To dream upon thy breast!

From the dark of their golden lids

Thy singing eyes look out,

Like doves in the olives hearing

The shepherd's jocund shout,

As he wandereth with his pipe

The sunny glen about.

I have opened mine eyes—

Thy beauty will not part,

But thy feet are dancing round me,

Lovely! that thou art—

The sweet breath of thine eyes doth fall,

Like odour on my heart!

Sleep on—sleep on—the silver flowers

A pillow for thy head may be,

While Evening with her band of hours

Sits by thee silently.

From Morning in the vine-yards straying—

Sweet child, so fair and meek!

She lieth down, and tired of playing,

Darkens the bright grass with her cheek.

One arm upon her eyes she foldeth,

O'er which her hair is softly fann'd,

And still with fainting grasp she holdeth

The lilies in her hand.

Oh—wake her not! the forest streams

With balmy lips are breathing rest;

Nor stir the garland of sweet dreams

Which Sleep hath bound upon her breast.

These are three volumes of spirit-stirring scenes, understood to be written by Captain Trelawney, the friend of Lord Byron. They are said to embody many incidents of the early life of the writer, though portions are too strongly tinged with romance to belong to sober reality. The Younger Son is driven from his native hearth by a cruel father. His proud spirit revolts at such oppression. He sings with Byron

And now I'm in the world alone,

Upon the wide wide sea;

But why should I for others groan,

When none will sigh for me.

His father intends him for the church, but instead of being sent to Oxford, he is taken to Portsmouth, and shipped on board a line of battle ship, the Superb, as passenger to join one of Nelson's squadron; but through delay he falls in with the Nelson fleet of Trafalgar, two days after the deathless victory. He returns to England, and is sent to Dr. Burney's navigation school. He next sails for the East Indies, and at Bombay he falls in with an adventurous stranger, whom he is minute in describing, "to account in part for the extraordinary influence he gained, on so short an acquaintance," over his mind and imagination. He became his model. The height of his ambition was to imitate him, even in his defects. Thenceforth his life of adventure begins. In its progress, he describes many beautiful scenes in the East with touching enthusiasm, and some of his pictures of luxuriant nature are admirably painted.

We pass over these to the heroine, at Port St. Louis:

"Zela had the blood of a fearless race. She had been bred and schooled amidst peril always at hand. Not having learnt to affect what she did not feel, she crossed ravines, wound along precipices, and waded through streams and rivers, not only without impeding us by enacting a pantomimic representation of fears, tears, entreaties, prayers, screaming, and fainting, but she was such a simpleton as not even to notice them, unless, in the usual sweet, low tone of her voice, to remark that they were delightful places to sit in, during the sultry part of the day; or she would stop her pony over a precipice to gather some curious flowers, drooping from a natural arch; or to pluck the pendant and waving boughs of the most graceful of Indian tress, the imperial mimosa, sensitive and sacred as love, shrinking from the touch of the profane.

"'Put this,' she said, holding out a branch, 'in your turban; for I am sure in some of these hollow caves and dreary chasms the ogres live; they feed their young with human blood, and they love to give them the young and beautiful. Put it in your turban, brother,—since you say I must not call you master;—and never frown,—I do not like to see it, for then you are not so handsome,—I mean, good, as when you smile. Do not laugh, but take it. It will preserve [pg 158] you from every spell and magic. Nothing bad dares come near it.'

"While crossing a sandy level, suddenly she started, as her eye caught some object. Without stopping her horse, which was ambling along, she sprang off, and ran up a sand hill, like a white doe. Never having witnessed any thing like this before, I was so astonished that she was returning, ere I could overtake her to ask if an ogre had lured her with his evil eye. 'O, no,' she cried,—'look here! You like flowers, but did you ever see any so lovely as this?—Smell it,—'tis so sweet, that the rose, if growing near it, loses its beauty and fragrance, from envy of its rival.'

"Certainly I thought she was bewitched. It was a glaring, large, red bough, full of blowzy blossoms, and yellow berries, with a musky, foeted odour. 'Why,' I exclaimed, 'you have as much reason to be jealous of old Kamalia, your nurse, as the rose to be jealous of such a scraggy bramble as this! Faugh! the smell makes me sick.'

"I suppose I was instigated to make this rude speech by her fondling and kissing it. Her dark eyes expanded; and she seemed, for an instant, to view me with astonishment, then with sorrow; as they closed, I perceived that their brightness was gone, and the long, jetty fringe, which arched upwards as it pressed her cheek, was covered with little pearly dew-drops. The branch fell from her hand under my feet, her sprightly form drooped, and the tones of her voice reminded me of the time when she hung over her dying parent, as she said,—'pardon me, stranger! I had forgotten you are not of my father's land. This tree covered my father's tent, sheltered us from the sun, and kept away the flies, when we slept in the day. Our virgins wreathe it in their hair, and, if they die, it is strewed over their graves. So, I can't help loving it better than any thing. But, since you say it makes you sick, I won't love it, or gather it any more.' Then her words became almost inarticulate from sobbing, as she added,—'Why should I wear it now? I belong to a stranger!. My father is gone!'

"I need scarcely say that I not only returned the flowers, and pleaded my ignorance, but I went up to the hill, and pulled up the tree by the roots. 'Sweet sister,' said I, 'I was only angry with it because you abused the favoured tree of our country, the rose. But now, as the sun shines on it, and I see it nearer,'—looking at her,—'I do think the rose may envy it, as the loveliest of my country women might envy you. I'll plant it in our garden.'

"'O, how good you are!' she exclaimed; 'and I'll plant a rose-tree near it, and they shall mingle their sweets; for our love and care of them will make them live together without envy. Every thing should love each other. I love every tree, and fruit, and flower.'

"Still I observed, as her thin robes were disarranged, that her little downy bosom fluttered like an imprisoned bird panting for liberty; and, to turn her thoughts from what had pained her, I said,—'Do not fear, dear Zela. That is the last stream we have to cross; and then we shall ride over that beautiful plain.'

"'O, stranger!' she replied, 'Zela never feared any thing, but her father, when angry; and then, those who feared not to gaze on the lightning, when all the world appeared to be on fire, feared to look in his face. Then his voice was louder than the thunder, and his lance deadlier than the thunderbolt. Last evening, when you talked to that tall man, who is so gentle, you looked like my father; and I thought you were going to kill him, and I wanted to tell you not; for I have read his eyes, and he loves you much. It is very bad to be angry with those that love us.'

"'Oh, you mean Aston! No, dear, I was not angry with him. I love him too. We were talking of the horrid cruelties practised on the poor slaves here; and I was angry at that.'

"'I wish I knew your language! How I should have loved to hear you! And then I should have slept; but being ignorant of that, I did nothing but weep, because I thought I saw you angry with one that loves you.'"

"It was only in Zela's absence that I could dwell on her portraiture. She had just turned her fourteenth year; and though certainly not considered, even in the east, as matured, yet, forced like a flower, fanned by the sultry west wind, into early developement, her form, like its petals bursting through the bud, gave promise of the rarest beauty and sweetness. Nurtured in the shade, her hue was pale, but contrasted with the date-coloured women about her, the soft and transparent clearness of her complexion was striking; and it was heightened by clouds of the darkest hair. She looked like a solitary star unveiled in the night, The breadth and depth of her clear and smooth forehead were partly hidden by the even silky line from which the hair [pg 159] arose, fell over in rich profusion, and added to its brightness; as did the glossy, well-defined eye-brow, boldly crossing the forehead, slightly waved at the outer extremities, but not arched. Her eyes were full, even for an orientalist, but neither sparkling nor prominent, soft as the thrush's. It was only when moved by joy, surprise, or sorrow, that the star-like iris dilated and glistened, and then its effect was most eloquent and magical. The distinct ebon-lashes which curtained them were singularly long and beautiful; and when she slept they pressed against her pale cheeks, and were arched upwards.

"That portion of the eye, generally of a pearly whiteness, in hers was tinted with a light shade of blue, like the bloom on a purple grape, or the sky seen through the morning mist. Her mouth was harmony and love; her face was small and oval, with a wavy outline of ineffable grace descending to her smooth and unruffled neck, thence swelling at her bosom, which was high, and just developing into form. Her limbs were long, full, and rounded, her motion was quick, but not springy, light as a zephyr. As she then stood canopied beneath the dense shade of that sacred Hindoo tree, with its drooping foliage hanging in clusters round her, in every clasped and sensitive leaf of which a fairy is said to dwell, I fancied she was their queen, and must have dropped from one of the leaves, to gambol and wanton among the flowers below. Running to her, I caught her in my arms, and said, 'I watched your fall, and have you now, dear sprite, and will keep you here!'—pressing her to my bosom.

"'Oh, put me down! You hurt me,—I have not fallen,—oh, let me go!'

"'Will you promise then not to take flight to your leafy dwelling, in that your fairy kingdom-tree?'

"'What do you mean? Oh, let me go,—you'll crush me!'

"I gently placed her on the ground, and told her my fears. The instant I unclutched her, she ran to her old attendant, scared like a young leveret; and this was my first embrace of my Arab maid.

"That it may not be considered I exaggerate, when speaking of the Arabs in India generally, I must refer the reader to what a recent, learned, and unprejudiced traveller says of them: 'The Arabs are numerous in India; their comparative fairness, their fine, bony, and muscular figures, their noble countenances, and picturesque dress, intelligent, bold, and active,' &c.

"Zela's father was all this, and her mother a celebrated beauty brought from the Georgian Caucasus, and twice made captive by the chance of war. After giving birth to Zela, she looked, and saw her own image in her child, blessed it, and yielded up her mortality. Is it to be marvelled at, that the offspring of such parents was as I have described, or rather what I have attempted to describe? For I am little skilled in words, or words are insufficient to represent what the eye sees, and the heart feels."

We must return to these very attractive volumes.

A Mistake.—In consequence of some transposition by which an announcement of the decease of a country clergyman had got inserted amongst the announcements of the marriages in a country paper a few days since, the announcement read thus: "Married the Rev. ——, curate of ——, to the great regret of all his parishioners, by whom he was universally beloved. The poor will long have cause to lament the unhappy event."

New Bankrupt Court.—One of the inferior judges, whose salaries are, by the Act, to be paid out of the fees, seeing that the whole amount was absorbed by the chief, observed to an associate on the bench, "Upon my word, R——, I begin to think that our appointment is all a matter of moonshine." "I hope it may be so," replied R——, "for then we shall soon see the first quarter."

The same humorous judge had listened to a very long argument on a particular case in which the counsel rested much upon a certain act of parliament. His opponent replied, "You need not rely on that act, for its teeth have been drawn by so many decisions against it, that it is worth nothing." Still the counsel argued on, and insisted on its authority; after listening to which for a good hour, his lordship drily remarked, "I do believe all the teeth of this act have been drawn, for there is nothing left but the jaw."—Literary Gazette.

Criticism.—A print of a wounded leopard is described by a contemporary as "a powerful exhibition of animal agony." Did our critic ever hear of vegetable agony?

Humbug.—A correspondent of the Times says "Every body is not acquainted with the etymology of the word [pg 160] Humbug. It is a corruption of Hamburgh, and originated in the following manner: During a period when war prevailed on the Continent, so many false reports and lying bulletins were fabricated at Hamburgh, that, at length, when any one would signify his disbelief of a statement, he would say, 'You had that from Hamburgh;' and thus, 'That is Hamburgh,' or 'Humbug,' became a common expression of incredulity."

A Clincher.—An American paper says, this is the method of catching tigers in India:—"A man carries a board, on which a human figure is painted; as soon as he arrives at the den, he knocks behind the board with a hammer; the noise rouses the tiger, when he flies in a direct line at the board, and grasps it, and the man behind clinches his claws in the wood, and so secures him."

Franking Letters.—The Princess Augusta asked Lord Walsingham for a frank; he wrote one for her in such detestable characters that, at the end of a week, after having wandered half over England, it was opened, and returned to her as illegible. The Princess complained to Lord Walsingham, and he then wrote the frank for her so legibly, that at the end of a couple of days, it was returned to her, marked "FORGERY."—The Town.

A Confessor was caugh t'other day rather jolly,

Who observed, "When a man has committed a folly,

If he has any sense left, hastens straightway to me,

When, confessing his guilt, I can soon set him free;

But how hard is my fate! for when wrong I have done,

Absolution's denied me by every one;

In which case, that I may from conscience escape,

Take refuge from thought in the juice of the grape."

Signs.—To trace the origin of signs would be an amusing relaxation for the Society of Antiquaries. Who could have imagined that "bag o' nails," was a corruption of the Bacchanals, which it evidently is from the rude epigraph still subjoined to the fractured classicism of the title? In the same manner the more modern "Goat and compasses" may be identified with the text of "God encompasseth us," which was a favourite motto amongst the ale-house Puritans.—Blackwood's Magazine.

Half-honesty.—A few nights since a friend gave a hackney-coachman two sovereigns instead of two shillings for his fare; when the coachman turned sharply and said, "Sir, you have given me a sovereign," keeping back the other; for which supposed honesty he was rewarded.

Proxy.—In 1436, we find the Bishop of Hola, in Iceland, whimsically enough hiring the master of a London merchant ship to sail to Iceland as his proxy, and to perform the necessary visitation of his see; the good prelate dreading in person to encounter the boisterous northern ocean.

Swelled Ankles at a Discount.—In the year 1699, when King William returned from Holland in a state of severe indisposition, he sent for Dr. Radcliffe, and showing him his swollen ankles, while the rest of his body was emaciated, said, "What think you of these?" "Why truly," replied the doctor, "I would not have your majesty's two legs for your three kingdoms." This freedom was never forgiven by the king, and no intercession could ever recover his favour towards Radcliffe.

Judge Rumsey was so excellent a lawyer that he was called the Picklock of the Law.

Commerce and Theft in every age and country have gone regularly together. Commerce accumulates riches, supplies the commodities to be stolen, supplies therefore the temptation, and puts the temptation in the way. Mercury was the God at once of Peace, of Merchants, and of Thieves; and it is not very long since an African king said he designed to send his son to Europe, "to read book and be rogue like white man."

Footnote 1: (return)Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, &c.

Footnote 2: (return)United Service Journal, Jan. 1832.

Footnote 3: (return)I did not observe them take the trouble of wrapping up the ingredients together, as is customary in India; but some would eat the betel leaf, previously dipping it in some lime (made from burnt coral) which he held in his hand, and ate the areka-nut afterwards; they had no tobacco to eat with it, nor did I hear them inquire for any.

"This work is exceedingly valuable, and may be considered as an Encyclopaedia, to which the most eminent of their time are constantly contributing."—New Monthly Magazine, March.

Printed and published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; G.G. BENNIS, 55, Rue Neuve, St. Augustin, Paris; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.